|

Yesterday Ausra and I went to an organ recital at St Casimirus church by Dr. Cristian Rizzotto and this inspired me to share some of my views on recital programming.

Imagine you are an organist who is invited to play an hour long recital. You naturally have to think about what music you will play. There are various approaches to this challenge. Some organists prefer to play only famous organ pieces so that listeners perhaps would recognize them. Some - only unfamiliar ones - because famous pieces are boring to them. Some - play a mixture of familiar and new music. Some - dedicate their program to some theme or to one particular composer or historical period or country. Whatever I choose to do I think one principle should always be kept in mind - a balance between a contrast and unity. If I play music which is too unified in character, then after 15 minutes or less it becomes boring. If I play music which is too contrasting - then people can't focus their attention for a longer time and can't find some common ground which also results in a boring experience. What do I mean about unified character? Well, it could be similar tempo (only fast, only slow), similar mood (only sad or only joyful), similar key (only major or only minor), similar dynamic level (only soft or only loud), similar pitch level (only high or only low), similar registration (only principals, only flutes, only strings or only reeds), similar writing style (only polyphonic or only homophonic music). But again if too much contrast is also not good. It might sound contrary to the logic but if I mix all these elements too much without any order, then listeners can't find a unifying element of my recital. When I improvise an hour long recital I always am conscious about the rule of contrast and unity as well. It doesn't matter that this music sounds for the first time and has never been written down before but listeners still can feel general idea pretty well. But above all I have to be conscious of the rule of contrast. It's like scenes of a good movie. They usually last 1 or 2 minutes and they seem to vary between positive and negative charge. So a lot of organ pieces are like that too. Every one or two pages you will find something new, something contrasting. As in a slow movie you could have long slow motion scenes, in organ music too you could have one mood last for 5 or even 10 minutes. But that's rather an exception than a rule. But of course, all of the above is my personal opinion and somebody else might have a different view. What I find boring, other might find exciting and vice versa. It's a fine art and not a science to program your organ recital well. I would say there isn't any silver bullet to this. One has to try out everything and figure out what works for them personally.

Comments

My friend James Flores asked me this question: "Were you going to do improvisations at Notre Dame, Paris, before the church caught fire? Or was that a duet recital with Ausra? I would love to know what you were planning to play." I think it would be a good idea to write a separate post about it. Everyone knows that the famous Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris caught fire and now this building needs restoration. The two organs inside of it apparently didn't burned down but I'm sure major or minor reparations will be necessary because of smoke and water that they suffered in the process. Notre Dame has a long-standing tradition of Saturday night organ recitals where the best organists from around the world come to play a 40 minute recital. The line is quite long because there are so many requests. After you send your CD recording, 3 cathedral organists evaluate it and decide if you have what it takes to play the magnificent Grand Organ at Notre Dame. Ausra and I passed this test but we had to wait for several years to be invited. Originally I had to play this summer (August 31, 2019) and Ausra - next summer (July 11, 2020). The rules of performance is that they don't allow improvisations, don't allow organ duets. So we had to propose 2 separate programs each for them to choose and indicate our favorite. My choices were: Program 1:

Program 2: (Favorite) ("Amber Soundscapes: Organ Music from Lithuania")

Ausra's choices were: Program 1:

Program 2 (Favorite):

They have selected my 2nd program choice (favorite) with Lithuanian music and for Ausra - 1st program with with music of J.S. Bach, Alain and Franck. I'd like to share with you my composition "Veni Creator", Op. 3 which I would have played at Notre Dame in Paris this August (I played this piece at Co-Cathedral of St John in Valletta, Malta last May): Ausra let me share her video of Andante in D Major by Felix Mendelssohn, one of her favorite pieces that she has ever played on the organ at Vilnius St. John's church in Vilnius (in general Mendelssohn's music works really great there): Because of fire all future recitals at Notre Dame had to be postponed and I think they have put their recitalists on waiting list when the great organ will be operational again.

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start Episode 269 of Secrets of Organ Playing podcast. This question was sent by Howard. He writes: One suggestion I have for your program is to diversify the focus to other kinds of instruments especially large British and American instruments that have pistons and toe studs. A program on the recommended piston settings for a ~30 min recital on an organ with say 6 General and 6 each of Divisional pistons would be great. Thanks. So obviously, this type of situation where you play modern instruments--not only British and American--is very common, Ausra, right? A: Yes, but what kind of problem is it? I don’t really comprehend the question, I think. V: Howard probably wants to know what kind of pieces you could play on an organ with general and divisional pistons. Anything! A: Anything; you could play anything, basically. V: If you have the opposite situation: a mechanical--purely mechanical--historical organ, let’s say from the 17th century or 18th century, then your choices are very limited. A: Sure; but on a modern instrument, with that combination system of pistons, you could play anything. V: Right. It doesn’t mean all the pieces will sound equally well or interesting... A: That’s right. V: But you surely could play anything. A: Because if you are playing a purely mechanical instrument, you are limited not to choose pieces that need a lot of registration changes. V: Sudden registration changes. A: Sudden, yes. Because it’s sometimes simply impossible to do all of them. But if you have a pistons system, that’s not a problem. V: Okay, so our friend Paulius is about to play a 30min recital in our cathedral in Vilnius. And we could discuss, a little bit, what he’s playing. And yes, he’s using that combination action. It’s not the same as pistons and toe studs as in British and American instruments, but it’s still modern type of combination action, where you can program in advance and push the button when you need it to change. Right? A: Yes. V: So it’s the same situation. I could imagine that Paulius could travel to another city with a modern organ with pistons and toe studs, and perform the same thing all over again. A: That’s right. I think sometimes it’s very nice when you can set up your registration in advance, and then to just press a button when you need to change it. V: Mhm. A: That’s what we did in London. V: Well, exactly, yes. So Paulius is playing a program with 5 or 6 pieces, maybe 5 pieces, and he’s using 5 combinations, one for each piece. And I’m helping to turn pages for him, so I know closely what he is doing. So basically, without giving too specific names of the pieces (because they’re less frequently performed and not well-known), we could give simple, general ideas, right? First of all, you need variety, contrast--right, Ausra? A: That’s right. V: Loud/soft, fast/slow, major/minor. What else? Those 3 are the main contrasts you should be aware of in your program. So it’s not good to play everything fast, right? Or everything slow, or everything loudly, or everything very softly, or everything just in a major key. Although it would be possible, of course, if it’s a festive occasion. Or just in a minor key--it would be perhaps too sad. You need variety. At least 1 or 2 pieces-- A; Well, what could you say if you have...let’s say, the general, as Howard told, six general pistons, what would you do? What would be your registration suggestion--what would you keep on those six general pistons, let’s say, if you would be a church organist? V: Probably for general...If I’m really scared to do the stop changes by myself, right, and I want to create a system where I could just sit on the bench and play whatever is in front of me, and I would push the button, and it will sound sort of okay--not, perhaps, perfect, but okay--so then, the six piston combinations would probably be pianissimo, piano, mezzopiano, mezzoforte, forte, and fortissimo. Sort of like Mendelssohn recommends, this kind of dynamic gradation. A: And what would you use for divisional pistons? Would you do some combinations for like solo voices, with you know, reeds or cornet stops? V: Obviously, yes, because you need to have solo registration sometimes in the RH or in the LH, and the other hand could play the accompaniment. I would check my instrument for nice solo stops: cornet, as you mentioned; krummhorn; oboe; trumpet. What else? Vox humana sometimes works well. Those few are the main ones. Oh, flute--flute combinations, like 8’-4⅕’, 8’-4⅓’, or just and 8’ flute and a third, 8’ flute and 2⅔...It’s possible to have variety in your colors. A: Okay, then you have an instrument with pistons. Do you use the sequencer, if you have one, or not? Do you think it’s a good idea to use a sequencer? Let’s say your organ has not 6 general, but many pistons, like we had at Pease Auditorium at Eastern Michigan University. Have you used the sequencer? V: Yes, I did--I have. And I would use it if I’m playing my pieces from the beginning until the end without stopping, for a performance like this, for a concert; and this is useful because you don’t have to worry about pressing the correct number of pistons. A: But yes, and what will happen if you would miss to push it once, or you would push twice instead of once? V: Then you would have a different registration. A: I know, but then you would be screwed! Don’t you think so? V: Obviously, yes. Obviously you have to be really careful; it has those disadvantages, too. But it’s a big help, you know, if you’re a traveling organist, used to one particular type setting with toe studs and pistons, then you don’t have to worry about where this piston is, under which key--number 2 or number 4 is. You just look where the sequencer is--sometimes to press it with your foot, sometimes with your hand. A: And I think the advantage of having piston and toe stud system is, you only need to program your registration for a particular registration once, and then you have it. Next time you come back to rehearse, you don’t have to set it up again, so it saves time. V: Exactly. Local organists will probably tell you what number to use... A: That’s right. V: What memory level. And you’re free to do whatever you want within that memory level. So, that’s the idea about using toe studs and pistons for registration changes, right? It saves a lot of time, but you have to also think about divisionals, right, so that your RH registration and LH registration would have variety. A: Yes, true. V: Mhm. One last thing, Ausra: On a big organ with, let’s say, 100 stops, would you ever play without a combination system--or just pulling the stops by hand? A: Well, I might do that, but probably not during a recital. V: I did that for trying out the organ at St. Paul’s Cathedral, when I improvised for maybe 5 or 6 minutes. I created those registration changes, and even dynamic changes, with my hands only. But you know, I was free to create whatever I wanted, because I was creating the music spontaneously. If you’re playing from a sheet of music, you’re restricted by what’s in front of you. A: Yes. V: And that’s why combinations and pistons are helpful. A: True. V: Thank you guys; this was an interesting discussion. We hope this was helpful to you. Please send us more of your questions; we love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice… A: Miracles happen.

This blog/podcast is supported by Total Organist - the most comprehensive organ training program online. It has hundreds of courses, coaching and practice materials for every area of organ playing, thousands of instructional videos and PDF's. You will NOT find more value anywhere else online...

Total Organist helps you to master any piece, perfect your technique, develop your sight-reading skills, and improvise or compose your own music and much much more... Sign up and begin your training today. And of course, you will get the 1st month free too. You can cancel anytime. Check it out here Here's what one of our students is saying: I really like the sharing. It's interesting to see what other organists are working on and how they go about learning new pieces. (Anne) Would you like to receive the same or even better results that Anne is getting? If so, join 80+ other Total Organist students here. By Vidas Pinkevicius (get free updates of new posts here)

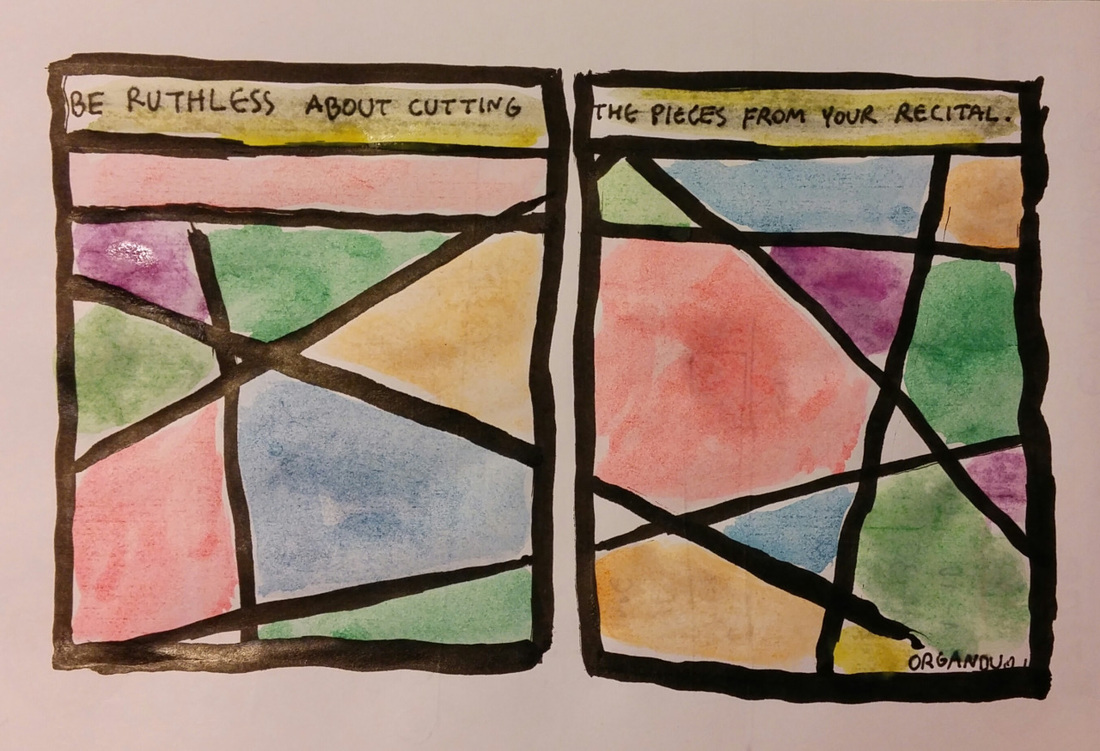

Today I went to practice to church for my upcomming December 17 Christmas organ music recital "In dulci jubilo". It was the first time I played it entirely non-stop and timed it. 92 minutes. It's too long, isn't it? Unless the music demands it, at St. John's we usually aim for about 50 minutes of non-stop music. With registration changes it would be about an hour. So I will have to shorten the program quite a bit. Here's how I will decide: I will listen to my gut feeling. I will look into my heart and I'll know what to play. Not very helpful, isn't it? How to translate it into normal language? Well, there are 3 kinds of pieces on my program so far: 1. Music I like. 2. Music I feel I have an obligation to play. 3. Music I can't live without. So for this recital I will most definitely play pieces from category No. 3, and a little of No. 2 and probably nothing from No. 3 (if it's enough). This way my program gets shortened without sacrificing my integrity. How do you decide what pieces to keep and what to leave out in your recital program? What would you do, if you had to play an organ recital on an unfamiliar instrument in a foreign country and wanted to connect with your audience? Watch this video with insights from me and Ausra. Did we miss something? Share your ideas in the comments. This question is much broader than simply playing organ compositions better during recital. It involves things like relationship of the organist to the listener, general musical education level of the listeners and their expectations, among other things.

Having this in mind, here are a few basic ideas which may help you to ensure that your recital will be appreciated by the audience. 1. Know your listener. What are his dreams, wants, desires, problems, fears? What keeps him awake at night? What is his worldview? How do you encounter him in a way that he trusts you? What are you trying to change in your listener? 2. Connect with your listeners through stories. Story-telling during the recital is a powerful tool which an organist should take advantage of. You can give interesting facts and details about the composer, the music, and the instrument which your audience can relate to. This way people can get much more out of your recital. 3. Choose a repertoire in a meaningful way. Remember that it's the listener that matters, not you. If you play average music for average people, there won't be much connection with your listeners. Instead, if you could program a remarkable recital with pieces that your listeners care deeply about, then you might be on to something. Remember the principle of variety - slow-fast, sad-joyful, loud-soft etc. Thematic recitals work splendidly in this case. 4. Keep in mind your instrument. Try not to play the music which doesn't work for your type of organ. Organ repertoire is vast and surely you can find an interesting program which suits your instrument well. 5. Develop your relationship with listeners beyond your recital. Start a blog, write a newsletter, create a video lecture or two, collect emails through a hand-out during the recital, interact with your fans through social media. These things really help you connect and lead your fan base. A final note: less is more. In case of doubt, always program less music than you want. It's better to leave the listeners wanting for more than to be annoying and overwhelming. What things do you use to keep your audience engaged during your recitals? Share your thoughts in comments. Are you wondering what kind of organ music selections are suitable for Bachelor's organ degree recital? In this article, I will give you a list of pieces by Buxtehude, Bach, Handel, Vierne, Langlais, and Franck.

1. Praeludium in C, BuxWV 137 by Dieterich Buxtehude. One of the most famous of all of Buxtehude's organ works will serve well for the opening of your recital. This is a perfect example of multi-movement North German Baroque Stylus Phantasticus writing. This work is also known as Prelude, Fugue, and Chaconne in C major. 2. Chorale Prelude "Komm heiliger Geist, Herre Gott", BuxWV 199 by Buxtehude. This is an ornamented chorale prelude - a perfect example of Buxtehude's style. This piece will make a good contrast with the preceding and following pieces. 3. Prelude and Fugue in G Major, BWV 541 by Johann Sebastian Bach. A joyful prelude with elements of Ritornello form. You will find a complex Stretto section towards the end of the fugue. 4. Chorale Prelude "Nun komm' der Heiden Heiland", BWV 659 by Bach. A very famous chorale prelude from the collection of Great 18 Chorales (Leipzig Chorale Preludes). Slow tempo and fascinating ornamented chorale melody in the right hand part. 5. Trio Sonata No. 1 in E flat Major, BWV 525 by Bach. This is the easiest of all of 6 trio sonatas by this composer. However, the organists will still encounter many technical challenges which have to be overcome at the Bachelor's degree recital. 6. Organ Concerto Op. 4, No. 5 in F Major, HWV 293 by George Frederic Handel. This is the shortest of 6 most famous organ concertos by Handel. It consists of four contrasting movements: Larghetto, Allegro, Alla Siciliana, and Presto. 7. Allegretto, Op. 1 by Louis Vierne. A rarely performed early work of Vierne of moderate difficulty. Nice ABA form with charming oboe melody in the right hand. 8. Meditation from the Suite Medievale by Jean Langlais. Very colorful French style modal writing. Slow tempo makes it a wonderful preparation for what is coming next in your program. 9. Chorale No. 3 by Cesar Franck. This is perhaps the most famous and the easiest of all of 3 chorales of Franck. A perfect closing piece for your recital - very dramatic work with a beautiful slow middle section. Take any or all of the above pieces and start practicing for your recital today. The compositions from this list constitute a recital of approximately 1 hour of duration which is an optimum length for organ recital. They provide a welcome variety in character, mood, tempo, mode, keys, and registration for positive listener experience. By the way, do you want to learn my special powerful techniques which help me to master any piece of organ music up to 10 times faster? If so, download my free Organ Practice Guide. Or if you really want to learn to play any organ composition at sight fluently and without mistakes while working only 15 minutes a day, check out my systematic master course in Organ Sight-Reading. Are you wondering what kind of organ music selections are suitable for Bachelor's organ degree recital? In this article, I will give you a list of pieces by Buxtehude, Bach, Handel, Vierne, Langlais, and Franck.

1. Praeludium in C, BuxWV 137 by Dieterich Buxtehude. One of the most famous of all of Buxtehude's organ works will serve well for the opening of your recital. This is a perfect example of multi-movement North German Baroque Stylus Phantasticus writing. This work is also known as Prelude, Fugue, and Chaconne in C major. 2. Chorale Prelude "Komm heiliger Geist, Herre Gott", BuxWV 199 by Buxtehude. This is an ornamented chorale prelude - a perfect example of Buxtehude's style. This piece will make a good contrast with the preceding and following pieces. 3. Prelude and Fugue in G Major, BWV 541 by Johann Sebastian Bach. A joyful prelude with elements of Ritornello form. You will find a complex Stretto section towards the end of the fugue. 4. Chorale Prelude "Nun komm' der Heiden Heiland", BWV 659 by Bach. A very famous chorale prelude from the collection of Great 18 Chorales (Leipzig Chorale Preludes). Slow tempo and fascinating ornamented chorale melody in the right hand part. 5. Trio Sonata No. 1 in E flat Major, BWV 525 by Bach. This is the easiest of all of 6 trio sonatas by this composer. However, the organists will still encounter many technical challenges which have to be overcome at the Bachelor's degree recital. 6. Organ Concerto Op. 4, No. 5 in F Major, HWV 293 by George Frideric Handel. This is the shortest of 6 most famous organ concertos by Handel. It consists of four contrasting movements: Larghetto, Allegro, Alla Siciliana, and Presto. 7. Allegretto, Op. 1 by Louis Vierne. A rarely performed early work of Vierne of moderate difficulty. Nice ABA form with charming oboe melody in the right hand. 8. Meditation from the Suite Medievale by Jean Langlais. Very colorful French style modal writing. Slow tempo makes it a wonderful preparation for what is coming next in your program. 9. Chorale No. 3 by Cesar Franck. This is perhaps the most famous and the easiest of all of 3 chorales of Franck. A perfect closing piece for your recital - very dramatic work with a beautiful slow middle section. Take any or all of the above pieces and start practicing for your recital today. The compositions from this list constitute a recital of approximately 1 hour of duration which is an optimum length for organ recital. They provide a welcome variety in character, mood, tempo, mode, keys, and registration for positive listener experience. By the way, do you want to learn my special powerful techniques which help me to master any piece of organ music up to 10 times faster? If so, download my free Organ Practice Guide. Or if you really want to learn to play any organ composition at sight fluently and without mistakes while working only 15 minutes a day, check out my systematic master course in Organ Sight-Reading. Have you ever thought what successful concert organists have in common? They all think outside the box. They try to be different than their competitors which makes them unique. In this article, I will show you how thinking outside the box in programing organ recitals can help you to achieve success as a concert organist.

If you want to become successful in giving organ recitals, try to be different from the majority of organists. Think of what can you do differently than anybody else in the organ world? Think of your listeners. If there are many organ concerts in your area, you should be thinking of what will propel your audience choose your concert instead of others. In other words, why they would go to your recital? You should think about the program of your concert very carefully and try to make it unique. You see, the majority of organists play organ recitals which consist of a mixture of pieces from various historical periods and national schools of organ composition. Although this approach works perfectly fine when programming organ recitals, it will not necessarily make your recital unique. Consequently, the listeners might not be drawn to your recital because they will think of it as one of many others and not something extraordinary which shouldn't be missed. Possible solutions to this issue might be giving your recital a unique title, programming it around a specific and colorful theme, including informative and/or entertaining verbal presentations and explanations about organ pieces and composers in your program, and even thinking about the involvement of members of the audience. Use the above tips and think outside the box in your preparation for your organ recital today. With time, this approach will put you in a situation when you can become a leader in your field and you will be considered as an expert by others. Consequently, being an expert will give you success you deserve as a concert organist. By the way, do you want to learn my special powerful techniques which help me to master any piece of organ music up to 10 times faster? If so, download my FREE Organ Practice Guide. Or if you really want to learn to play any organ composition at sight fluently and without mistakes while working only 15 minutes a day, check out my systematic master course in Organ Sight-Reading. Have you been to an organ recital which lasted too long or too short? I have. For organists the question of timing is really important because if they play a recital which is too short, the listeners will be disappointed and if it's too lengthy - they will be bored and want to leave. If you are wondering what is the optimum length of an organ recital, read this article.

I have found that the optimum duration of a recital without intermission should be around 60 minutes (with stop changes). However, the ideal length of a recital depends on other factors, such as how cold it is in the room. If the recital is during winter time and the church is not heated, it is probably better to make it shorter than usual, perhaps 30-45 minutes. Otherwise, people might catch cold during your playing. If the building is heated all year round, you can make the length of a recital as usual - around 60 minutes. In cases when the program consists of long cycles, such as Clavierubung III, the Art of the Fugue, 18 Great Chorale preludes or other collections by Bach or other composers, you can plan for a longer duration. This is acceptable because people will expect it to be longer. If the recital is with intermission, each part could last around 40-45 minutes (encores not including). This is usually the case in large concert halls. The length of the recital does not matter so much in cases where the organist is of world class caliber. Then the listeners would not want him or her to stop playing anyway. In such cases, one or more encores is normal. Generally speaking, it is better that listeners would want for more music than to become bored. In other words, if your program is just a little under 60 minutes (around 50-55 minutes) it is OK. There is no need to try to squeeze in an extra piece or two if the program is ideally balanced. In addition, you have to remember that people who are going to attend your recital, might be frequent concert-goers and they might be used to the normal recital format of 60 minutes. I usually plan around 50 minutes of pure music. That leaves me around 10 minutes for registration changes between the pieces. One more thing is important to remember here. If you plan on talking during the recital, try to calculate the time of your presentations so that recital would not last too long. The bottom line is this: your listener's time is as precious as yours - don't make your recitals too lengthy. By the way, do you want to learn my special powerful techniques which help me to master any piece of organ music up to 10 times faster? If so, download my FREE Organ Practice Guide. Or if you really want to learn to play any organ composition at sight fluently and without mistakes while working only 15 minutes a day, check out my systematic master course in Organ Sight-Reading. |

DON'T MISS A THING! FREE UPDATES BY EMAIL.Thank you!You have successfully joined our subscriber list.  Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas

Authors

Drs. Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene Organists of Vilnius University , creators of Secrets of Organ Playing. Our Hauptwerk Setup:

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

This site participates in the Amazon, Thomann and other affiliate programs, the proceeds of which keep it free for anyone to read.

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed