|

Vidas: Hello and welcome to Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast!

Ausra: This is a show dedicated to helping you become a better organist. V: We’re your hosts Vidas Pinkevicius... A: ...and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene. V: We have over 25 years of experience of playing the organ A: ...and we’ve been teaching thousands of organists online from 89 countries since 2011. V: So now let’s jump in and get started with the podcast for today. A: We hope you’ll enjoy it! V: Hi guys! This is Vidas. A: And Ausra. Vidas: Let’s start episode 624 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Diana, who transcribes fingering and pedaling from our videos, and she writes that: “Sometimes I read a treble clef like a bass clef...” Vidas: I don’t know if it’s a common problem or not, Ausra. Ausra: Well, actually, it’s a very uncommon problem. The problem is usually that people read bass clef as treble clef, but not otherwise. So, I really don’t know what to say and how to help! Vidas: Yeah, because if you start your musical training with the bass clefs, so it becomes your native clef, so you learn it first, and then every other clef becomes like an addition to that, so you then judge, let’s say, treble clef by the notes of the bass clef. Ausra: Well, do you know many musicians who start their training with bass clef? Because I personally don’t. Vidas: Exactly. That’s what I meant, you know, common experience is starting from the treble clef nowadays. Maybe she means that she’s mixing up treble clef with bass clef, but the other way around, could be. Ausra: Yes, that would be a very common problem for people, but I would say that the more you play in different clefs, the easier it gets, because usually this problem is for beginners only. Do you mix clefs, Vidas? Vidas: Yes, I mix them all the time, but intentionally, because I know 10 clefs. There are five C clefs on every line which indicate treble C, there are two F clefs like a bass clef and the baritone clef. They indicate the note tenor F. And there are three... or two… two G clefs. The descant and the treble clef. And I probably should mention that there is another one; an extra F clef to basso profundo. Right, Ausra? Ausra: Yes. And are you comfortable with all of those clefs? Vidas: No, I don’t use them everyday, but probably the four of them are the most common: treble clef, bass clef, then alto clef and the tenor clef. But I also use very often soprano clef. What about you? Ausra: Well actually, I use four of C clefs very often, so soprano, mezzo-soprano, alto, and tenor, but not so often the baritone, and of course the treble and bass clefs. I don’t use this contra- clef or another F clef. Vidas: You teach students at school about those clefs. Right? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: What do they say when you teach them? Ausra: They hate them, and they hate me! Vidas: “Why do we need them?” Right? Ausra: Yes! Actually, not really, because among my students, there are some who use C clefs in their daily life, because they play alto cello and like trombone, so they are sort of used to other clefs as well. Vidas: But I mean when you explain why they need them, what do you say? Ausra: Well, I explain how the tradition of writing music was, that paper was very expensive and the use of these clefs allow us to omit ledger lines, so and in that case you save space, you save paper. Plus, it was tradition that each voice has its own clef. It was really comfortable. And I give them for an example Mozart’s Requiem. Vidas: “Lacrymosa?” Ausra: Yes, because it’s in the textbook, but I guess other parts of and movements of the Requiem are written in the same manner. Vidas: To me, there is another benefit of using clefs that changing clefs and using them in my daily training, because if you have a theme written, let’s say in the treble clef, the theme of a musical, idea four measures long or two measures long, whatever your theme is, or even an entire chorale or hymn written in the treble clef, and you want to improvise on that theme, one of the techniques that makes your improvisation more colorful and interesting is to transpose this theme into other keys. Not to play in one key, which is okay for a short time, but to change to the dominant key, to the relative key, to the subdominant key, to the relative of the dominant, relative to the subdominant, those closely related keys, let’s say, and one of the ways to easily do this is by changing the clef. You read the notes as they are on the stave, but in your mind, you change the clef, and therefore, you read different notes—you transpose them to different keys—adding different accidentals, of course. Ausra: But that way you really need to be closely familiar with these keys and clefs. Vidas: Of course! Ausra: Because what I do when I have to read, let’s say, from the C clefs, I just transpose back of an interval. And I’m very good at doing that. Do you think it’s possible it’s also one of the right ways to do it? Vidas: Well, yes, it’s not difficult if you are transposing just a major or minor second up or down, but other than that, you need to then switch something in your head. Right? So either you switch the clef, or you switch the position of the note on the staff. You can choose whichever feels more natural in this particular situation. Ausra: You know, for me, for example, it’s very easy when I have to transpose things a second or a third below the given melody, and therefore in order to use all these C clefs, I’ll just have to switch in my head between treble and bass clef, and I can do that very easily then. Vidas. Right. So I have this training, “Transposition for Organists, Level 1,” which teaches you to transpose 4-part hymns at sight fluently. And the goal of this course is to help people perfect their hymn transposition skills so that they would be able to transpose any 4-part hymn at sight fluently and without mistakes by the intervals of the half-step and the whole-step up and down. So this is the first step. The first level. Then the second level would be probably wider intervals, like a major or minor third up and down, and then a perfect fourth up and down, a fifth, and so forth. Ausra: Well, but you know in a practical way, I wouldn’t say that you need to go to wider intervals, because you rarely will encounter a case that you have to transpose so far away. Vidas: Yes, the widest interval that is probably practical, I would say, is perfect fourth up. Ausra: Well, I would go to a major third, probably. Vidas: But, you know, if you want to transpose from C major to G major, what do you do then? Right? Ausra: Well, yes. Vidas: From the tonic to the dominant. Ausra: But lets say we are talking now about hymn transposition, and all the vocal music including hymns are related to a human voice, to a diapason of human voice, and I don’t think any of us have such a wide range in our diapason, so I don’t think you need to transpose in such wide intervals. Vidas: No, but if your goal is to learn to improvise, transposition is one of those steps. Ausra: Well, yes. Vidas: Trust me. I know. Ausra: Anyway, I don’t have any trouble to transposing anything to any key, so I don’t think it’s really for me, your teaching. I could teach you. Vidas: Yes. Which intervals would you teach me? Ausra: Perfect octave! Vidas: Perfect octave. Ausra: That’s the easiest transposition! Vidas: Yeah, but people who need to perfect their, let’s say, transposition skills would find this course really helpful. This course is not written, of course, in different clefs. It’s in treble clef. Or not… let me think… Oh yeah, actually, I’m looking at the picture of the course, and yes, we have alto clef! Yes, we have transposition by the clefs, so it applies to those people who want to read the clefs, too. Ausra: Well, because what I’m thinking is that if you are transposing only by a second or a third, then you could think about a given interval and which direction you are transposing by a second or by a third, but if you need to transpose by a wider interval, then probably you need to imagine a different clef. It’s easier that way. Vidas: Yes. And the wider the interval, the more difficult it becomes. So level 1 is just major or minor seconds. So I suggest people start from there and see how it goes for 12 weeks in a row. That’s the length of the course. Ausra: Well, another way would be if you imagine all the music in the scale degrees, then you could use that skill to transpose, and I don’t think then the right interval would be a problem. Vidas: Yes, but then this music needs to stay in one key, like a hymn. But in hymns, sometimes, we have also temporary excursions to different keys like the dominant or to the relative key as well. So in that instance, in your mind you have to switch to another key, and then to another scale degree. That’s complicated a little bit. Ausra: Isn’t that self-explanatory? Vidas: Maybe, but we have to explain everything none-the-less. Right? Ausra: Well, if you are smart enough to understand that the key is changing in a concrete part, so I don’t think it would be a trouble for you to switch to other keys’ scale degrees. Vidas: You haven’t forgotten how you first learned, let’s say, about those clefs and transposition twenty years ago or more… it’s really... Ausra: Yes, it was a very long time ago! Vidas: Yes, so I think people start really from scratch and they need to do the basic stuff. Ausra: Probably 30 years ago! Vidas: Could be. We are very old. So guys, check out this course, “Transposition for Organists Level 1” and spend some time with those clefs and see if that helps you internalize them and my experience tells me you need one month for one clef to perfect it. Ausra: Well, for some people it’s trouble to play in treble and bass clef enough that they struggle for years and still cannot do that. Vidas: I mean one month, seven days a week, eight hours per day, you know! Ausra: Like a full-time job, yes? Vidas: Yes! For one month! Alright guys, please send us more of your questions; we love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice, Ausra: Miracles happen. V: This podcast is supported by Total Organist - the most comprehensive organ training program online. A: It has hundreds of courses, coaching and practice materials for every area of organ playing, thousands of instructional videos and PDF's. You will NOT find more value anywhere else online... V: Total Organist helps you to master any piece, perfect your technique, develop your sight-reading skills, and improvise or compose your own music and much much more… A: Sign up and begin your training today at organduo.lt and click on Total Organist. And of course, you will get the 1st month free too. You can cancel anytime. V: If you like our organ music, you can also support us on Patreon and get free CD’s. A: Find out more at patreon.com/secretsoforganplaying

Comments

Vidas: Hi guys! This is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 424 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Irineo. He writes: Hello back there maestro! Now that was an interesting discussion you had. But I wonder, which other clefs are there besides two G, two C, and one F? Those are the ones I’m familiar with. And while transposing, you mean when you’re writing a score or improvising? Thank you. Very truly yours, Irineo V: Interesting that Irineo knows two G clefs, right, Ausra? A: Yes, because that other one, old-fashioned G clef is not common nowadays. V: Mm hmm. We could actually survey all ten clefs, right? A: Sure. V: Remind people to take a look at them and pick and choose. Sometimes they’re useful, right? Ausra, did you use some clefs today? A: Yes, I used one of the C clefs today. V: On what occasion? A: Well, we were playing Bach’s aria from one of the cantatas. V: Mm hm. Mein gläubiges Herze, right? A: That’s right. And we had to play soprano parts. So it was written in soprano clef, so. V: And my part had the bass clef in the left hand and in the right hand bass clef, but somehow it changed constantly between bass clef and tenor clef, I believe. So, starting with the G clefs, we have to, as Irineo says, the first one is well known violin clef, where G is on the second line. Treble G. A: That’s right. And we are always counting the lines from the bottom. V: Yes. As Ausra said, if you have G on the first line, that’s called an old French clef from the 17th century, for example. A: That’s right. And it means that the G note is on the bottom line. V: Mm hmm. And it was popular for string music, right? Violins played from such a clef. So, it’s actually higher than normal violin clef. Because the lower the clef, the higher the sound. A: Yes. That’s how it works. V: And clefs are used to avoid ledger lines. A: That’s right. V: Mm hmm. A: So, especially in the old time when paper was very expensive, people wanted to save space, and instead of writing extra lines, we would just change a clef. V: Then we have the familiar F clef, where on the fourth line, we have, what, tenor F? A: That’s right. V. Mm hmm. Which is called bass clef. A: Yes. Probably it’s the most common after the treble clef. V: Mm hmm. A: So it’s used quite a lot in music, for the keyboards, and for some of the strings, and for some of the wind instruments. V: Mm hmm. But actually, there are three F clefs, from the history of music. A: So tell us more about the other two F clefs. V: Mm hm. If you put the F on the fifth line, you have the baritone clef. So, it’s the same like bass clef, the figure of the clef, but put two lines higher, on the top line. On the fifth line, right? So, which means that on the fifth line, you have tenor F. What else? If you have the F clef on the third line… A: Yes, the middle line. V: Middle line. Then you have basso profondo clef. Which is lower than the normal bass clef. One third lower. Right? But, strangely, if you look at the similarity between F clef and G clef, imagine you have F on the middle line, then there is no similarity. But if you have baritone clef on the fifth line, you know you, we have violin clef, second octave F too. So people can use in their mind, transposition to the violin clef, but very high. Two octaves higher. And that would be much easier than reading from the baritone clef. A: Well, for me I would say it’s fairly enough to have [one] treble clef. One F clef and five C clefs. It gives me plenty of opportunities to transpose, and to sightread music. V: What about C clefs? I talked about G clefs and F clefs. I give the C clefs to you. A: Well, I use them every day. V: Okay. So, tell us more! A: Well, there are five C clefs, and each of them marks the note C. And if we start at the bottom line, we have soprano clef. And if we go up, we have mezzo soprano clef. And on the middle line we have alto clef. Then tenor clef. And on the upper line is baritone clef. And it always marks the note of the C of the first octave, of the middle octave. V: Mm hmm. A: And these keys are very, you know, fun, and very easy to use to transpose things. V: So you are saying baritone clef is on the fifth line. A: That’s right. V: So I was wrong, actually, when talking about F clef, which was called baritone. In F clef, baritone should be on the middle line, then, right? I said on the fifth line. A: Okay. V: On the fifth line is basso profondo. A: Basso profondo, yes. V: So, it’s kind of confusing sometimes, if you don’t use it every day. But for which occasion those ten clefs can be used? I would say for two occasions. If you want to improvise based on the theme transpositions, like maybe a few, you’d have to constantly change the key of the subject, then you don’t have to remember the subject itself. You just look at the score and change the clef itself, right? It sounds difficult, but after a few months of work, it’s not that hard. A: Yes, because I think you have to be quite advanced in order to manage all these clefs very easily. V: And the second occasion I think is for geeks. You know what a geek is? A: Yes, I know what a gig is. V: Geek. G-e-e-k. A: No, I don’t know that. V: Computer geek, for example. A: I know g-i-g. V: Yeah. Computer geek is a guy usually, with very thick glasses, and he knows everything about computers, but nothing about anything else. Like a connoisseur about certain subjects. So if you are very deep into early music, for example, and you always prefer to practice and sightread from facsimiles, from old manuscripts and old prints, modernly, in modern times reproduced. Then you need those clefs because people were writing. A: Well, and still, even if you know you work on, not exactly like very old music, but in some editions, some nineteenth century editions, of, let’s say Bach. V: Mm hmm. A: You can find pieces that are written in clefs. V: Oh, yes. A: For example, Peters Edition, I have played myself, you know, the third part of Clavierübung in Academy of Music when I was studying. And one of the chorales was, you know, written in C clefs. V: Mm hm. A: So what I had to do, I was too lazy to transpose them, I mean, rewrite them down in, you know, like treble and bass clefs. So I just played in clefs right away. V: And also, if you study Bach from that Bach Gesellschaft Ausgabe, from the nineteenth century edition which was started with Mendelssohn times, right? And it was widely used in the nineteenth century, those original clefs, they didn’t change Bach’s clefs. They used Bach’s notation. And since Bach used C clefs, Bach gesellschaftausgabe also used same kind of clefs. A: Plus, if you study music, let’s say Mozart’s requiem, for example, famous piece. It’s all written, actually he used three C clefs and bass clef. V: Right. Soprano, alto, tenor, and bass clef. A: That’s right. Because it’s written for four voices. So, and sometimes it’s good to study old scores. Compare them to the modern editions. V: Yes. Not only it’s a good exercise in the mind, but you get to know the composer deeper. A: It’s true. Plus there are instruments like cello that use C clef constantly, and other instruments, wind instruments for example. V: Yes. Orchestral instruments sometimes use C clefs. And then, for example, if you play Brahms. Chorale preludes by Brahms. From nineteenth century, right? But because he used polyphonic techniques that he loved from Bach’s times, plus, he added some chromatic harmonies of course. He used actually, C clefs. Even in today’s editions, you will find C clefs in Brahms’ compositions. So you need them. A: Well, yes. If you don’t want to be sort of challenged. V: Clef-challenged. A: That’s right. V: Yes. At first, we all are clef-challenged, and we only know treble clef in the first grade, right? But somehow, six months later, we manage to play with the bass clef starting. It’s not that easy, and we struggle for a few years, actually, we struggle with bass clef. A: Well, it comes easier for some and harder for others. V: Mm hmm. A: It’s, you know, a very individual thing. V: When I was sightreading Art of the Fugue by Bach, original notation, I discovered that you need about one month for each particular clef to be comfortable with it. So if you have ten clefs, you need ten months. And that’s it. Plus, if you need combinations of clefs, for two voices, or three or four voices, then you need additional time. But if you are just sightreading one voice, you can do it in ten months, pretty much, without any struggle. A: That’s right. Which is your favorite clef, Vidas? V: Soprano. A: Mine, too. It’s easier. V: Mm hm. But for awhile you didn’t like soprano. A: I know. I liked alto. V: Mm hm. A: That was my first choice. But now I think I prefer soprano. And then probably tenor in the third place. V: Do you think that soprano clef could unlock the doors of our house? A: I don’t think so. V: Alto maybe. A: I don’t think so. But we can unlock very interesting music for you, very beautiful music. But anyway, Irineo asks, do we need to know transposing using clefs in writing or in improvisation? So, I would never mean that you would need to write down your transposition. I don’t see any sense in doing that. V: As an exercise, you have theory classes, right? A: Well, but it takes only like one lesson just to try to do it. Because the most important part is that you could do it live, so you need to do it as a transposition of real music piece by playing it. V: And plus, there are now computer notations, all those softwares that do automatically for you, everything transposed, and change clefs automatically, so you don’t need that. But, if you want to play, yes, you do need. A: And it’s a very useful skill, especially is you are a church musician. And especially if you are working with choirs, and if you are working with your soloists with bass clef figures. Because you never know what we might want you to play. V: I remember exactly one wedding when soprano was sort of sick, and she asked me to transpose one third lower. So I used simply C clef in the right hand part and soprano, and treble clef in the bass, in the left hand. Soprano and treble, and that’s it. Very easy. A: True. V: Okay. This was Vidas A: And Ausra. V: We do hope this was useful discussion. Please send us more of your questions. We love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice, A: Miracles happen. DON'T MISS A THING! FREE UPDATES BY EMAIL. Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start Episode 183 of Ask Vidas and Ausra podcast. Today is a beautiful Wednesday, right Ausra? A: Yeah. V: Do you feel that Spring is coming in Vilnius, to Vilnius? A: Well, not yet but from tomorrow I think Winter will join us again. V: Do you, are you fed up with Winter? A: Yes. V: Me too. I somehow long for more green colors. A: Yes and no. The snow is getting awful. V: So guys I hope you have enough green in your part of the world right now and that you feel the Spring returning. Of course, if you are in Australia for example, then there is or in the summer hemisphere somewhere then it’s Autumn, right? A: Yes. V: After Summer and temperatures might be dropping a little bit too. A: That should be nice I think. V: OK. So let’s talk a little bit Ausra about organ playing. Today were going to go to our church to practice for the first time actually together our program for J. S. Bach’s three hundred thirty third birthday recital which will be in what, in less that two weeks from now. Were recording this a little bit earlier than you are probably hearing this. And of course, we’ll be playing organ duets, right, that I have transcribed or sometimes were using the original score. By the way do you like playing from original score Ausra, the Aria? A: Well it’s OK although I have to play from soprano clef. V: I have to play from two bass clefs. And you have to play from soprano and treble clef, right? A: Yes. V: Which C clef is your favorite? A: Now it’s soprano because I’m playing from it, so. V: Yes, soprano is kind of nice. A: But otherwise alto is OK too. V: You mean where C is in the middle? A: Yes. V: Not too bad I think. Was that always the case for you? A: Actually alto was my favorite first. But now it’s soprano. V: Is it because you play more on the soprano clef? A: Well I think it’s easier for me to transpose a third than a second. That’s funny but that is how it is. V: What about a perfect fourth? Do you like those clefs which let you transpose a perfect fourth? A: No, I don’t like those. V: So. A: It’s harder then. V: So if you transpose from a treble clef that would mean G on the second line would have to become C, right? A: Yes. V: And this would be what, mezzo-soprano clef. A: Yes. V: Do you like it? A: Not too much. V: Why? Because it’s far away from the original. A: Yes, that’s true. V: It’s very old clef. I don’t think it’s used often enough today. A: I don’t think either. I think two clefs are used nowadays, that's alto clef and tenor clef. V: Tenor clef, right. Cello is playing from the tenor clef sometimes. A: Trombone I think. V: Bassoon too I think. A: Yes. V: Sometimes in the upper range. And who plays from the alto clef. A: Viola. V: Viola. Is that all? A: Probably not but that’s the instrument I know the best that plays from alto clef. V: And of course singers, right? Alto. A: Of course. V: If they sing from original scores. A: Sure, but singers use all those C clefs if they use the old scores. V: Um-hmm. Yeah. A: Even Mozart’s Requiem is you know original is written in C clefs except bass, of course. Bass is I think is in the bass clef. But other three voices are written in C clefs. V: Yeah. Bass has its own clef. F clef. And Ausra, from your solo compositions that you are playing. You are playing Bach’s BWV 552 E flat Major Prelude and Fugue. What is the most frustrating part for you? Everything or not so much? A: I like this piece so much although sometimes I get frustrated by the length of the prelude. Sometimes right in the middle I just feel that you know wow. There is still so much music to go. V: Do you lose your concentration? A: Sometimes yes. V: What do you do then? Regain your concentration? A: Yes that’s what I am trying to do. V: What helps you to regain your concentration? A: Just think about music what I’m playing right now because sometimes my mind just travels somewhere. V: To warm places? Warm Spring? A: (Laughs) Not necessarily. To somewhere else. V: To the Caribbean. A: Well, no. V: Caribbean beaches where you can sit and drink Margaritas. A: I never was there. V: That’s why you dream about it. A: No, no, no. V: OK. Then for me, do you know what I’m playing? A: Yes I know what you are playing. V: Tell us. A: Passacaglia. V: OK. What else? A: And three chorale pieces from the Clavierubung Part III. So actually that’s what we are doing. I’m playing Prelude and Fugue and then playing three chorales. The Kyrie, Christe and Kyrie. V: And guess what is the most challenging for me? Which piece or a few pieces? A: I think all three of them are quite challenging. But the first Kyrie is my favorite, the first chorale. Especially that it is so chromatic. I love it. V: Do you feel Ausra, that the more you play the E flat Prelude and Fugue the more relaxed you are and the more you can enjoy it. A: Yes, of course but I don’t know how I will do in actual performance because when I played it a year ago it was, well it was a nightmare. I don’t remember actually how I did do it in performance. You said it went well but I just can’t remember it. I was so scared you know my mind just shut down. V: So when you say you sort of panic but it didn’t seem too obvious. A: But actually I played it on my auto-pilot. V: So you almost memorized it then. A: Well, I don’t know. Don’t ask me. I don’t remember how I did it. V: We could consult the recording. A: Yes. But actually that was because I haven’t played that piece before the last recital for what, like ten years. And that’s a long break for any piece. Especially so grand as this one. But now because I played it last year so I don’t worry about this year so much. Because if I could play it last year so now definitely I would be able to play it this year. V: That’s what I mean. The more you play the more you can enjoy it. And for me I don’t remember if I have ever played in public those three Kyrie, Christe, Kyrie. A: That’s a new piece for you. V: And I’m not feeling too relaxed with them. I have to work. A: But you know since I played entire Clavierubung way back for my last degree recital in Lincoln, NE I think these three Kyrie, Christe, Kyrie I wouldn’t say that the easiest of entire Clavierubung because each piece is challenging in it’s own way but, but, but, sort of I felt quite secure about playing these three particular chorales because there are some much trickier ones as for example Allein Gott this is you know trio texture. V: That’s what I am playing next. A: I know and for example Vater Unser. V: Um-Hmm. A: Those are more challenging I think, than these three. Kyrie, Christe, Kyrie. Because you know tempo is not so fast in them and you could feel quite secure when playing them. V: Bach was a master of writing advanced music and although it sounds simply you know it isn’t. In reality it is quite complex. Polyphonically, rhythmically, metrically, and organistically, right? Excellent. What about the Passacaglia, do you think that I’ll be able to play it better than last time? A: Now remind me when was the last time you played it? V: (Laughs) I don’t remember. A: I don’t remember either, so. V: I might have played it from the eighteenth century score, but that was very foolish idea of mine. So now I’m playing this from the regular score. A: I think you will do fine. V: Will you help me playing if I panic. A: I can sing. V: Which voice. A: Bass. V: Bass, that’s my part. A: I’m just making fun of you. V: You know sometimes I sing together with you the duetto part. A: And I hate it. V: Why? My voice is like a Nightingale. A: (Laughs.) Wow. V: If not a Nightingale then which bird you would compare it to me? A: You know that black one. V: So you like crows? A: I’m just pretending that I don’t. V: So you say that my voice is like a Nightingale then? A: Maybe like a cuckoo. V: So I can sing a minor third down. A: Well cuckoo not only can sing this interval. Sometimes it’s major third. Sometimes it actually augmented fourth. V: And what birds voice remind you when you sing? A: I don’t know. I don’t have a nice voice. V: Today when were going to play in church I’ll try to encourage you to sing and we’ll find out which bird you are. OK? A: I think if we both try to sing we will kicked out from the church and we will scare tourists. V: But then we tell all about that in the next podcast conversation, right? A: Yes. Of course we are making jokes because when we work in church we often sang Psalm. Our voices are not so bad. V: Don’t spoil everything. Don’t reveal the punch line. OK. Thank you guys. This was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: Please send us more of your questions because we love helping you grow. And remember when you practice… A: Miracles happen. By Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene (get free updates of new posts here)

How do you feel when clefs change in the middle of your organ piece? A lot of my students get confused. They stumble, they slow down, they even miss the change and continue to play as if nothing happened. What can you do to speed up your clef reading? For starters, practice parts with a more challenging clef twice as much. You see, one clef takes about one month of focused practice to get more comfortable. If you find it difficult to read the bass clef, devote just one month to exercises with this clef. It will feel like hell at first but it gets easier with time. If you want even more challenge, take a right hand of your organ piece and transpose it to the bass clef. Organists should feel at ease with both the treble and the bass clefs. If you insist upon it for some time, you'll find a lot of things that are much more challenging than changing clefs. By Vidas Pinkevicius

There are two kinds of clefs that organists most often use: the treble clef and the bass clef. One is easy to learn, another - not so much. That's because we learn treble clef from the start and the bass clef - only later. The challenge is that both are necessary to play organ music well. Nobody can tell you what proportion of sight-reading you should practice with your left hand in the bass clef. The best advice is just do it every day until it's so easy that you don't think about it. Kind of like walking...

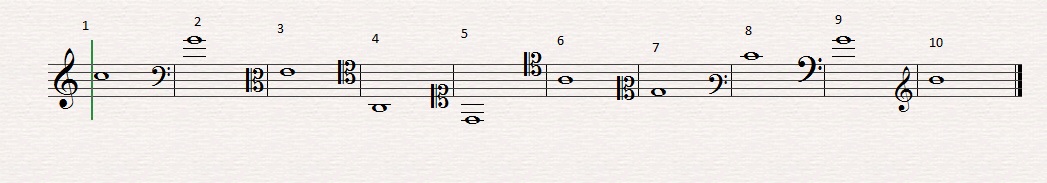

Even though you can see 10 different clefs in the above picture, in reality there are only 3 kinds of clefs: G, F and C. G clef (as in Nos. 1 - Treble clef and 10 - Descant clef) indicates where is treble G (or g'). F clef (as in Nos. 2 - Bass clef, 8 - Baritone clef and 9 - Basso Profondo clef where is tenor F (or f). C clef (as in Nos. 3 - Alto clef, 4 - Tenor clef, 5 - Soprano clef, 6 - Baritone clef and 7 - Mezzo soprano clef) indicates where is treble C (or c'). |

DON'T MISS A THING! FREE UPDATES BY EMAIL.Thank you!You have successfully joined our subscriber list.  Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas

Authors

Drs. Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene Organists of Vilnius University , creators of Secrets of Organ Playing. Our Hauptwerk Setup:

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

This site participates in the Amazon, Thomann and other affiliate programs, the proceeds of which keep it free for anyone to read.

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed