|

Vidas: Hello and welcome to Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast!

Ausra: This is a show dedicated to helping you become a better organist. V: We’re your hosts Vidas Pinkevicius... A: ...and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene. V: We have over 25 years of experience of playing the organ A: ...and we’ve been teaching thousands of organists online from 89 countries since 2011. V: So now let’s jump in and get started with the podcast for today. A: We hope you’ll enjoy it! V: Hi guys! This is Vidas. A: And Ausra. Vidas: Let’s start episode 638 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Graham, and he comments on my recording of the practice session of his Idyll. So he writes,: “Wonderful, Vidas! It was written in the summer of 2020 during the first lockdown of the Covid pandemic. I saw a competition advertised for a meditative piece for organ and this composition appeared nearly instantly! I do love Erik Satie's 'Gymnopedies' (I have heard you play No 2 on the organ!) and there is a strong French impressionist influence in this piece. It came together remarkably quickly from an initial improvisation to the finished composition as I was very near the deadline for submitting for the competition. As you know, I am not 'original' in my writing as I recognize everything I create is derivative - a fusion of everything I have ever heard or played. I love the music of Cole Porter and George Gershwin and Irving Berlin . . . so there is a trace of those songsters deep inside the piece as well. It sounds gorgeous on the Salisbury Willis - a sound I never expected to hear. THANK YOU!” Vidas: So Ausra, do you remember me playing this piece? Ausra: Yes, I remember it. Sweet little slow meditative piece. Vidas: Idyll. It’s like a pastoral scene from an antiquity time with lots of nature and maybe some animals. Ausra: I think it really fits the Salisbury organ very well. Vidas: Yeah, I enjoyed playing it. So what Graham writes in response to the style, did you hear Erik Satie’s influence here? Ausra: Yes, a little bit, yes! Vidas: The triple meter is kind of similar to Satie’s Gymnopedies (here is the score of organ arrangement of Gymnopedie No. 1). I don’t know how to pronounce it either. So yeah. I wonder if it’s difficult to create or improvise a piece like this, Ausra! Ausra: I think it depends on everybody’s skills! Vidas: So as a harmony teacher, what do you hear when you listen to this piece? Ausra: Well, as far as I have heard Erik Satie’s Gymnopedies, and I used to play them on piano, at least a few of them, they are strongly influenced by Jewish music, or at least that’s what I thought when I was working on them and when I heard them played. You played them on the organ. And of course in this Grahams piece, Idyll, I don’t hear that Jewish influence. At least not that remarkable. What do you think about that? Vidas: By Jewish you mean special modes, right? Special intervals in the scale… augmented intervals. Right? Ausra: Yes, and of course the minor keys. Vidas: No, probably most similar this with Satie’s work stem from the triple meter in my mind. But other than that, it’s like a major key, idyllic character, slow moving tempo, and in general a very gentle rocking sort of feeling. It’s like a little bit… remember we played this piece by Ad Wammes about the boat. Ausra: Yes, I remember it very well. Vidas: Something about the lake, summertime, breeze… Ausra: Yes there was sort of a like a suite out of like four movements. Vidas: And one of them was probably in triple meter, too. So I imagine lying on the bottom of a small boat in the middle of the lake on a hot summer day, and this boat gently rocks back and forth. I can hear water splashing on it, on the sides of the boat, and maybe some sounds from nature, you know, gentle breeze blowing, also. Sort of idyllic vacation feeling. Do you like this feeling? Ausra: Yes, especially now when it’s really cold outside. I would wish it would be summer and I could be on the lake! Vidas: Do you usually spend your vacations like that on the bottom of the boat? Ausra: Well, actually no, I don’t own the boat, so… Vidas: Yeah, it’s new to me, but I can just imagine how it would look. Looking, obviously, up to the sky, right, when you lie on the bottom of the boat. It’s a good feeling. Could this piece work as a liturgical music, too? Ausra: Of course. You could play it for communion. It wouldn’t hurt, definitely. Vidas: Even though it’s not based on any preexisting chorale melody or hymn tune. But the gentle character fits the liturgy well; especially for communion, maybe offertory, maybe at the beginning, too, for gathering, as a prelude. Right? Ausra: Maybe it’s too soft for a prelude. Vidas: Why too soft? Ausra: You would want something louder in order to quiet people who are walking downstairs. Vidas: Oh, you mean like Brenda? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: Tell us about it! Ausra: I think I already told about it a few times, about that comic strip that I saw when we were back as students at UNL, and there was an old lady in that drawing who actually had a hunting rifle, and she was sort of silencing the crowd for her prelude with a gun! Vidas: Right. That’s probably very symptomatic of the situation before the service in any church. Right? People gather and they talk, they haven’t seen each other for a week, probably, or longer, so any music that is played before the service is not on their radar just yet. Just like, obviously, the postlude after the service. Ausra: Yes, you finish the postlude and there is nobody left in the church. Everybody is having coffee. Vidas: And if you are playing a fugue as a postlude, then voices are enter one by one, and people leave one by one, which is not true. Right? Ausra: I think it’s nice that at least some people stay to listen the postlude and they applaud after that. Vidas: I was just going to say that people do not actually leave one by one, but they tend to leave in droves. Excellent. Shall we wish Graham to keep creating? Ausra: Sure! I think it’s a real gift if you can compose music, so just keep doing that. Vidas: And to make your pieces available, because it’s really hard to get! You have to write an email to the composer and the composer has to write you back with the score. It’s obviously complicated to both the would-be-performer and to the composer. It should be frictionless. I suggested that he could upload it to Sheet Music Plus and he could sell those scores, but Graham wanted for people to have them for free, so why not upload them to IMSLP like Petrucci Music Library? Ausra: Yes, I think that’s a great idea. Vidas: And it would be free, available instantly for anyone. Ausra: That way maybe more organists would get access to it and would perform it more often. Vidas: Yes, for this, we really hope this will happen in 2021. And please send us more of your questions if you have about the composition process, about performance issues that you encounter in the works you play for perhaps, we would like to help you out. And remember, when you practice, Ausra: Miracles happen. V: This podcast is supported by Total Organist - the most comprehensive organ training program online. A: It has hundreds of courses, coaching and practice materials for every area of organ playing, thousands of instructional videos and PDF's. You will NOT find more value anywhere else online... V: Total Organist helps you to master any piece, perfect your technique, develop your sight-reading skills, and improvise or compose your own music and much much more… A: Sign up and begin your training today at organduo.lt and click on Total Organist. And of course, you will get the 1st month free too. You can cancel anytime. V: If you like our organ music, you can also support us on Patreon and BMC and get early access to our videos. A: Find out more at patreon.com/secretsoforganplaying and buymeacoffee.com/organduo

Comments

Welcome to episode 516 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast!

Today it's my pleasure to introduce to you Paul Ayres who is a prize-winning composer, arranger, choral conductor, musical director, organist and accompanist from the UK. We are talking about his organ music. Vidas: Thank you so much, Paul for joining in this conversation! I'm very delighted to be able to talk with you through the internet. I came in the contact with your work some months ago when I found out about your fabulous Toccata for Eric. And you sent me other pieces to listen to and then I bought the entire Suite for Eric which was very exciting suite for me. And I'm actually learning and practicing it right now. Actually, before we started talking I practiced the Prelude and Fugue from this suite. Listen to the entire conversation You can find out more about Paul Ayres and his work by visiting his website at https://www.paulayres.co.uk. Relevant Links: a re-written version of J S Bach's Toccata and Fugue BWV 565 awarded second prize in the AGO Seattle Chapter 'Bach to the Future' composition competition online live recordings: https://youtu.be/lGxCCNq01Yw http://yourlisten.com/paulayresaudio/mostly-bachs-toccata-and-fugue Fantasy-Sonata on Over the Rainbow http://paulayres.co.uk/catalogue/404 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gbP5qiHzYD8 https://soundcloud.com/user-517413285/rainbow1 https://soundcloud.com/user-517413285/rainbow2 https://soundcloud.com/user-517413285/rainbow3 https://soundcloud.com/user-517413285/rainbow4 https://soundcloud.com/user-517413285/rainbow5 http://paulayres.co.uk/catalogue/404 Toccata (Fantasia) first prize in the Harrison and Harrison organ builders 150th anniversary composing competition http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M_fhV6Hh6vw http://yourlisten.com/paulayresaudio/fantasia-150-ayres-for-organ http://paulayres.co.uk/catalogue/318 Washington Toccata second prize in Washington DC AGO chapter composing competition [this one not performed nor recorded yet!] Aria (from Suite for Eric) https://youtu.be/j0bCdjBm6yA https://soundcloud.com/user350556481/aria-ayres http://paulayres.co.uk/catalogue/296 Mostly Bach's Toccata and Fugue in D minor https://youtu.be/lGxCCNq01Yw http://yourlisten.com/paulayresaudio/mostly-bachs-toccata-and-fugue http://paulayres.co.uk/catalogue/398 Concerto on I want to hold your hand https://youtu.be/PXCq2a_LcaU https://soundcloud.com/user-517413285/i-want-to-hold-your-hand-ayreslennonmccartney http://paulayres.co.uk/catalogue/359 Green Suite first prize in the Brindley & Foster composition competition 2010 http://paulayres.co.uk/catalogue/276 Adagio Cromatico on Michelle https://youtu.be/WGZcwocxMZM http://yourlisten.com/paulayresaudio/adagio-cromatico-on-michelle-paul-ayres http://paulayres.co.uk/catalogue/408 Toccatina on Here Comes The Sun https://youtu.be/idE2tyMWVKg http://yourlisten.com/paulayresaudio/toccatina-on-here-comes-the-sun-ayres http://paulayres.co.uk/catalogue/410 Trio on Ich steh' and Hey Jude https://youtu.be/dpd682Ko1SA https://soundcloud.com/user-517413285/trio-on-ich-steh-and-hey-jude-ayresbachbeatles https://soundcloud.com/user350556481/trio-on-ich-steh-and-hey-jude-ayres http://paulayres.co.uk/catalogue/388 Lament on And I love her https://youtu.be/07syFRJjGWE https://soundcloud.com/user350556481/lament-on-and-i-love-her-ayres http://paulayres.co.uk/catalogue/390 Funiculi Funicula Finale http://paulayres.co.uk/catalogue/407 Fantasia on Mission Impossible https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aGiGCMLIK98 http://paulayres.co.uk/catalogue/298 The Departure of the Queen of Sheba https://soundcloud.com/paul4141/the-departure-of-the-queen-of http://paulayres.co.uk/catalogue/242 Andrew Lloyd Webber Variations for cello and rock band (the entire album, transcribed for solo organ) http://paulayres.co.uk/catalogue/356 A Whiter Shade of Pale http://paulayres.co.uk/catalogue/357 Exite Fideles (based on Adeste Fideles) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3149lMJdysk http://paulayres.co.uk/catalogue/191 Variations on Es ist ein Ros entsprungen joint first prize in the New Zealand Association of Organists' composition competition https://youtu.be/9-Z1SmMbBUE https://soundcloud.com/user-517413285/es-ist-ein-ros-entsprungen-ayres http://paulayres.co.uk/catalogue/15 Evermore and evermore (based on Corde natus ex Parentis) http://paulayres.co.uk/catalogue/290 Advent Fantasia (using melodies Veni Emmanuel and Wachet Auf) http://paulayres.co.uk/catalogue/45 Herzlich tut mich verlangen http://paulayres.co.uk/catalogue/181 The Lord's my Shepherd (Crimond) http://paulayres.co.uk/catalogue/182 Veni creator Spiritus http://paulayres.co.uk/catalogue/245 Duo (from Suite for Eric) https://youtu.be/0oqsTjnU550 https://soundcloud.com/user350556481/duo-ayres http://paulayres.co.uk/catalogue/296 Intermezzo (from Suite for Eric) https://youtu.be/Fg6KQlmnNB8 https://soundcloud.com/user350556481/intermezzo-ayres http://paulayres.co.uk/catalogue/296 Wie schoen leuchtet der Morgenstern http://paulayres.co.uk/catalogue/180 Toccata on All you need is love http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xn_22eAr3Eg http://paulayres.co.uk/catalogue/243 I'm in my car right now, parked just outside the cultural center of the university and waiting for our secret training session to begin. They said, "Don't wear high heels..." Not sure why. I guess we'll find out soon enough.

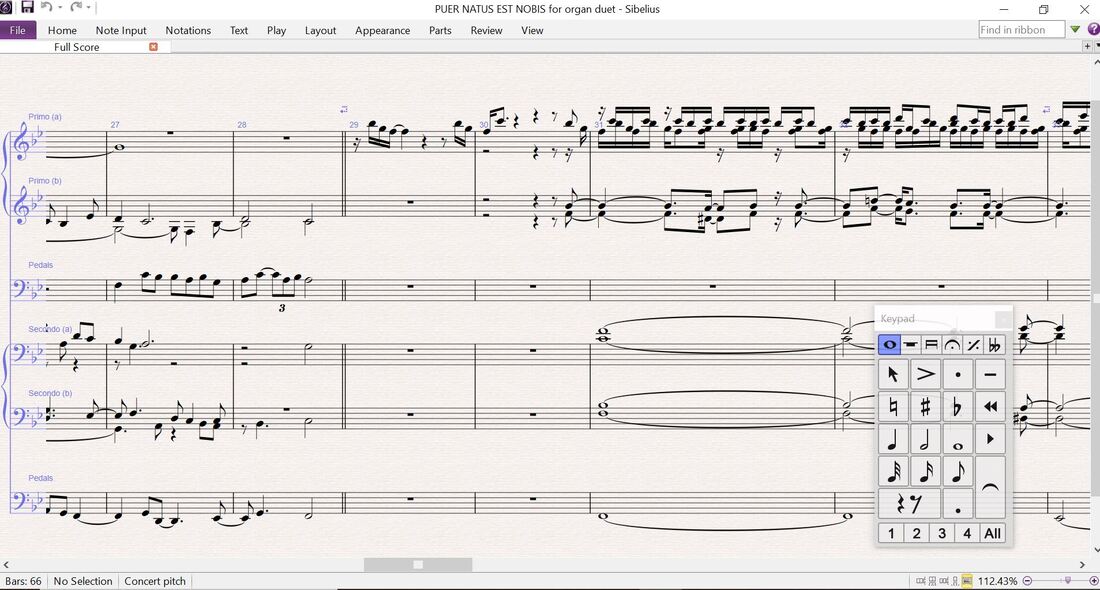

This week my main focus will be on composing "Puer natus est nobis" for organ duet, sight-reading new music, playing organ duets with Ausra, starting to practice Toccata by Paul Ayres, going to a couple long training sessions at the cultural center today and tomorrow, having Unda Maris organ studio rehearsal, interviewing my former organ professor Pamela Ruiter-Feenstra for the podcast, recording another organ demonstration for art students with sound experiments, preparing for Saturday's Harmony class and recital of my colleague at the church. This recital will be dedicated to the 150 anniversary of Lithuanian composer, organist and choir conductor Juozas Naujalis. I need to check if the posters are all printed out and prepare program notes. And of course I will be writing blog posts, creating podcasts and drawing Pinky and Spiky comics. Now I have to run to this secret training session because it will be starting in a few moments. I'm glad I'm not wearing my high heels today, haha! In the morning I worked on composing my new piece for organ duet "Puer natus est nobis." Yesterday I had all the material composed but today I noticed the middle part lacked interest, so I re-did it again into a fast-paced section. Will need to work on simplifying and clarifying the notation later on.

Then I submitted our letter of intent of participating at the international organ festival in Anyksciai and Ausra and I sight-read Tarantella Dementa by Carson Cooman. After lunch we again played another duet by Cooman and I drew a Pinky and Spiky comic on my 18th notebook. Later we watched Hunger Games on TV. Parts 1 and 2. This week I've been struggling with creating an interesting piece for organ duet. I find that it's difficult to control the texture when writing for four hands and four feet. When you make an interesting texture, it's possible to lose yourself in it and forget the flow of time, forget how the listeners would perceive it in motion.

For example, at first, I created a piece with one eighth note motion flow. It seemed interesting enough. But it went for 5 and a half minutes. The rule about keeping interest going is to change something before it gets boring. Usually it's less than 2 minutes. It's like scenes in movies. One scene usually lasts about 1 minute, sometimes up to 2 minutes. Of course, there are slow movies with long scenes but they are a separate breed. So I today thought about inserting a middle section in the piece. This had to add contrast. How about a smaller note values? Maybe 16th notes. And sure enough now my piece has 3 sections, like in ABA form - eighth-notes, 16th notes and eighth notes again. It doesn't mean this piece will be interesting when I finish it though. It just means I eliminated just one problem. Quite a few more to go.

First of all, I want to remind everyone who is planning to enter our Secrets of Organ Playing Contest Week 1 that less than 24 hours are left to submit your entry. We already have the first contest entry. Congratulations @savagirl4! The future belongs to the brave and curious.

And now let's go to the podcast for today. Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas. Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 367, of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Leon. And, he writes: Galsworthy encouraged Streatfeild to know three times more than she needed to about whatever she chose to write. Does it take three times the knowledge of music to be able to compose? V: So this question Ausra, is taken from our correspondence with Leon, and he sent me a link to the biography of an English author, Mary Noel Streatfeild, who is best known for her children’s book, including the ‘Shoes’ Book. And this citation which John Galsworthy, English novelist and playwright, that wrote the Forsyte Saga, basically suggests that Galsworthy recommended for Streatfeild to read three times as much as she writes as a writer, right? To read more than you would write. It makes sense, actually, right? You cannot really write anything of value if you are not knowledgeable about your field. You have to get expertise by reading many books. A: True and you have to increase your vocabulary. V: I just wrote to him that for example, Voltaire recommended reading 100 books in order to be able to write one. So it was maybe different area, different, maybe background. He was maybe talking about encyclopedic knowledge, not necessarily life experiences. But Leon is wondering about how it relates or translates to musical composition. A: Well, it’s obviously that since very early times, composers studied each others music. Think about young Bach, what he did when he copied the scores from his brothers library, at night in secret. It means that it meant a lot to him and he learned a lot from those scores. Because can you imagine just writing by your hand, copying all those scores? It’s a long process. V: And by this process, that was one of the main exercises to learn copying… A: Sure. V: Other composers music. A: And I think now we are missing this much because we are not copying by hand and sometimes it’s probably would be a nice thing to copy something by hand. V: I actually did… A: Just really internalize it. V: I copied C major invention by Bach. Taken not from modern edition but from his handwriting. A: Mmm-hmm. V: Just for fun, you know, like, Pamela is also very, Pamela Ruiter–Feentra, our former professor, is very enthusiastic about copying by hand so, she knows the value because she did the research about Bach and improvisation. So then, I thought maybe I could also try copying just one to see. I didn’t notice any miracles happening right away, but maybe that’s because it was just a single piece. A: You need to write down, to rewrite and copy all of his inventions. Anyway... V: Yes. A: Now I think we have all this modern technique that allows us to copy easily things. V: Too easily. A: Yes. Too easily. V: Mmm-hmm. Things get too fast for us. A: Yes. But now I think that it would be very beneficial if many young composers would try to study other composers as well not just create their own music. Because what is happening right now in Lithuania, maybe in other countries too, that there are so much more people who are creating music and composing music, that it’s sort of like a new fashion. V: Really? A: Really. Because, like in our school, earlier, we would have very little students who will study composition. But now it’s almost like a, I don’t know, infectious disease. V: You mean like a fashion? A: Yes, like a fashion. Let’s say if you are incapable of playing instrument well, or you are incapable of doing something in the music well, ‘oh, okay, I’ll be a composer’. That’s a new fashion and it’s just bad and it makes me really sick and upset and I think it’s a very, very, very bad thing—very bad tendency. V: You know what they say, Ausra, ‘those who cannot play, create. Those who cannot create, teach. Those who cannot teach, criticize’. (Laughs) A: Well, I guess there might be some part of truth of each of the saying, maybe not entirely true but there is certain true about it. And I cannot force myself to perform a music, by let’s say by a contemporary so-called composer that I cannot respect—that I know that let’s say he or she or whatever, cannot do something for themselves with the music. Because I know instances for example, people who have no, or I would say, a man who has no musical pitch… V: Mmm-hmm. A: Composes. And believe me, I have heard these stories both in the United States and in Lithuania as well. V: Mmm-mmm. A: Because now we have all wonderful technology, all this music systems, Sibelius and so on and so forth, that any of us can compose. V: It’s a double edge sword, or knife. A: But do I really need to spend my time, to waste my time of learning a composition that is written by somebody that… V: Cannot perform. A: True. V: Cannot play. A: And cannot hear what he or she writes. V: Uh-huh. By hearing you mean that they need to play back the music to them in order to hear it. They don’t hear it inside their head. A: Not only that, I’m not talking only about inner pitch, I’m talking about musical pitch at all. V: Really? A: Yes. In general. V: So serious then. A: It’s very serious. It’s really serious, so now when talking about contemporary composers you really need to select carefully that you wouldn’t waste time for worthless music. I’m sorry to say it but so it is—at least that’s my point of view. V: Wouldn’t you think that people somehow should—your not talking about people, your not suggesting for people to stop creating, no? You are advocating for people to start developing other skills in their vocabulary, that they could actually understand the music they’re creating, and even sometimes perform. If it’s their instrument of course. A: Well because if you would look at the back at the musical history, all the great composers, their performances, well, and they started by performing other composers music and studying other composers music. V: Mmm-hmm. A: And now some of these young composers, that they cannot play, that they haven’t studied enough other compositions, they start to create music of their own. V: You mean like reinvent the wheel? A: Yes. V: They don’t know what came before them, and they think ‘oh, I have a clever idea. Nobody else had it before, and maybe I will be unique.’ A: Well, be honest. By now, I think all those possibilities are almost exhausted… V: Mmm-hmm. A: And if you do something a little more creative than another, it doesn’t mean anything, at least for me. Because trying to compose without having this good musical education or this understanding about musical history, about other composers, not having any skills of yourself, it’s like building a house from roof. V: Maybe what hasn’t been done enough, is to create music out of combinations of various different elements. For example, let’s say you like this genre of the fugue, but fugues have been written thousands and thousands of times before. It’s nothing new. But you could take another genre and combine it with the fugue. And maybe it has been done also, so maybe you need three things to mix in this pot to be at least partly original. What do you think, Ausra? A: Yes, I think it’s a good thing. V: But for this to happen, just like Leon says, or Galsworthy, you need to be knowledge about other works that came before you and read a lot and basically sight-read a lot, study other works, so that you could take those elements with your, within reason. A: Yes. And you know what I’m talking and criticizing in this podcast, I don’t think it applies let’s say for church musicians. Let’s say you are an organist, and you really need to have a new hymn composed or any kind of composition for your liturgical works, you can easily do that, because you know what you really need. And it’s I think very fine and I encourage people doing that. V: Mmm-hmm. A: Because sometimes we really need to know good liturgical works right away and you know what, let’s say what our choir is capable of singing, or what we are able to play or what our congregation likes, but I’m talking about that sort of very high professional composers who pretend to very high professionals. V: Academic. A: Yes, academic, and who creates sort of non-sensical piece and want to push it to international festival to be performed, let’s say by a great orchestra. V: Mmm-hmm. A: I’m talking about these kind of things. V: Right. A: I’m talking that nowadays, maybe ambition of some young composers are way too high, for let’s say the beginners. V: But you know, what I can relate a little, at least a little bit, partially—I can understand a little bit why they are ignoring other composers, other works of previous generations—because they want to be original, right? And that’s the thing that matters—novelty, originality, uniqueness. And they feel that everything was created and so it’s better even not to bother with old stuff and start from scratch, in their mind. That’s how they think maybe. A: I’m not telling that you have to copy all composers, that’s not what I’m meaning, and that’s not what I’m telling. I’m just telling that before composing your own you need to know that history. It will enrich your understanding about things. V: Definitely. Yeah. A: Because I think it’s very fascinating that if you think about music that it’s only twelve different notes, and all that music was made and created out of only twelve notes. It’s truly amazing. V: Mmm-hmm. And if you know the history of music, you can better be equipped of creating the future of music. A: True. Because I really think that music needs to have substance. It needs to have it’s form. V: But again, this is within reason. I know one professor in musical academy in Lithuania who is probably world-class expert in musical history and musical theory in general, analysis. And he knows everything that there is to know. And he’s already in his 70’s I believe. And only a few years ago he started to compose, because he said to one of his students, ‘now I know everything, and now I’m ready to create.’ Which is kind of craze to me. A: Well I that preparation time for composing for every person is different. V: But waiting until you are seventy… A: I think it’s okay. V: Why? A: Well, sometimes it’s enough to write one genial composition for people to remember you. V: But don’t you think that this professor knew enough to start with, like twenty, thirty years ago? A: Well you just can do whatever you want with your life. You cannot do something others lives. You cannot enforce people to do what you want. V: Silence! Let’s listen to the snow. A: Vidas is, to wake up my words, because I don’t think he likes them so much. V: I’m just saying that, no, you cannot influence others, of course. You’re right. And... A: You can do influence. You can try to do influence, but you cannot force them to do what you want. V: Mmm-hmm. A: And sometimes I think when you want to make influence for somebody, you need to find subtle ways to do it, rather than push forward. V: Let me then clarify a little bit my thought: I think that particular professor didn’t create music, not because he wasn’t knowledgeable enough to begin with, maybe decades ago, but maybe he had another reason. He was telling official reason, and he had another true reason. What do you think? A: Probably yes. V: That’s more plausible explanation. A: Sure! V: Right? Because why did he start now? Maybe... A: Maybe now he has more free time. V: Oh! That’s right. That’s right. A: Because some people cannot create when they are under pressure under all kind of activities—working, raising family, doing all kind of stuff. And maybe now it’s time in his life when he can do it and enjoy it. V: Okay guys, we hope this was useful to you. Please send us your questions. We love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice... A: Miracles happen!

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 345 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. And this question was sent sent by Pauline. She writes: Hi, I have a question to ask here. I am a self learned electronic organist in church. I play hymns every Sunday together with another pianist. In order to create a more inspirational music for God & the congregation, who should be playing melody and who should be the accompanist? Thanks! V: Ausra, don’t you think that the organist and pianist both should be playing something more substantial, not only melody or accompaniment? What’s your opinion? A: Well, it depends on what kind of hymn it is, because some hymns actually work quite nicely on the piano, and some don’t work on the piano at all. So, you obviously need to look at the real of the hymn, and then decide what to do. V: But, I don’t think that, for example, a pianist could play the melody and the organist could only play the accompaniment in chords, or, for example, vice versa, that the organist could play the melody with the right hand, and the pianist would provide the accompaniment. This wouldn’t be... A: Of course I couldn’t agree more! I think in general, electronic organ and piano is a bad duet. I wouldn’t mix them both together. V: But, if you treat it like a Taizé music… remember, so, in Taizé, they have a basic chordal structure for a keyboard instrument, but then anything else that plays together, they play melodies and duets and trios and dialogues, and it sounds rather nice this way—polyphonic. A: Well, true, but I think if you would want to do something like Taizé, you would still have to have only one keyboard. And if you want to have some elaborations, you would need to add other instruments, such as flute, maybe...I think flute would work very nicely… and a violin, or any other solo instrument. V: Do you think that Pauline’s pianist could play two melodies—two separate and contrasting melodies in each hand as maybe two melodic instruments, a violinist and flutist, would do? A: Well, it’s possible. I’m not sure about how the final result would be. V: Or in the left hand, maybe he could imitate, maybe, cello, and in the right hand some kind of solo treble instrument, and create a nice dialogue. A: That’s a possibility although I don’t know how advanced they both are, and how well they could do that. Because, this kind of musicianship would take some improvisation skills. V: Right! This would be nice. I believe they could train themselves. What would be the first step? What would you do if, for example, you and I had to do this, or even in our house situation, I would play on the organ and you would play on the piano, and vice versa? That wouldn’t work, because our piano is not in tune with the organ. A: As is our organ, yes. V: But, in theory, maybe, I’m thinking…. Thinking in chords, this accompaniment, so to say, but melodic accompaniment could also think in chords that the organist is playing, or choir singing, and then play a lot of arpeggios and things like that. But not only arpeggios, make them melodic, make them meaningful. A: Somehow now, I’m thinking about that Geistliches Lied from Austria. Remember way back in the year of 2000, when we were in the church music courses in Salzburg. V: Yes, this is like a Christian popular music, but quality popular music, I think, because each instrument has its own part, and a very developed part. So, Pauline, maybe you could actually do something like this with your pianist. Maybe you could even write out the melody, or two melodies for your pianist, and maybe you could write out chords and things like that for yourself, right? Because to do this on your own on the spot would be too stressful. You need to either rehearse or write it out. A: Sure. And really, if you want to make everything very nice ask from the congregation. Maybe there is somebody who plays another instrument other than a keyboard instrument. That would really make things much nicer. V: And then, you could actually arrange any time of hymn for them, to add descants and treble solos, and maybe bass lines—alternate bass lines. A: Sure. Although, I don’t know how many and which stops this electronic organ has. But, if it has enough reeds, and other colorful stops, maybe the organ could then act as a solo instrument, and piano would provide accompaniment. V: Right. Then the organist needs to play maybe the treble part, and maybe the left hand could play the cello part. Right? A: Yes. That way, maybe the organ could be a solo instrument, and piano would accompany. V: Interesting. A: Although you need to check it on the spot, and I cannot guarantee that it will sound nice. V: And also, it depends on where the organ is located. In the back or in the front? A: How far is it from the piano? V: Mhm. How difficult it is to communicate and play together. So, it’s a lot of things to take in and to take into consideration in this situation. Do you think that organists usually have enough time to do such creative things in church? A: Well, I’m not sure. It depends on the situation. Usually, I think we all don’t have enough time for things. V: But usually, people are very appreciative, congregations are usually appreciative if you do a little more than is required from you. A: That’s true. V: Right? Her pianist could easily play the chords, and she could play on the organ what’s written in the hymnal, and that would be it. And nobody could complain, and actually nobody would have the right to complain, right? Because it’s quite enough if you play it nicely on both instruments. But if both of you do something extra, then people will notice, I hope. A: True. Do you think people always notice and appreciate new things? V: No, not always, but imagine if Pauline or her pianist, before the service, would come up and say, “My dear congregation, today, we have prepared for you something very special,” and the both of them would describe what they will be doing in, for example, the following hymn—the opening hymn. People would, I think, appreciate that. A: Well, yes, but it’s of course also a danger of elaborating too much, and adding too many things that the hymn might be unrecognizable, and people might not be able to sing it. V: And there’s always the danger of playing like in a concert setting. Right? Sometimes the clergy doesn’t like that. A: True, because, for example, for my case and my understanding of good hymn accompaniment, the most important thing for hymn accompaniment is to play in a right and steady tempo. This is actually what is the most required from the organists who are accompanists. Congregational singing. V: But, I mean, if it’s, let’s say, a special occasion, maybe a hymn festival, and they would like to do something more and more creative on a number of hymns during that festival, for example, then a few verse, not necessarily every hymn every verse should be done this way, but every once in a while to make it more colorful and more creative, that wouldn’t hurt. A: True, and I think it’s always easier if you have a choir at a church. It is a big help for singing congregational hymns, because they lead the congregation. V: Interesting. I would probably do such experiments. It’s all experiment… you don’t know what the result will be, but you don’t know until you try. And if you don’t try, you will always regret it afterwards, because you don’t know. Maybe it would have been worth it. Thank you guys, this was Vidas, A: And Ausra, V: Please send us more of your questions, we love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice, A: Miracles happen.

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start Episode 289 of Secrets of Organ Playing podcast. This question was sent by Osei. And he wants to become a great organist and a composer, but he struggles with fingering. That’s sort of a short question that he sent. A: But I find it very controversial, don’t you? V: Yes. If you want to become a great composer and organist, I think your challenges should be bigger than fingering. A: I think so, too. Because if you are still struggling with fingering, it means that you are at the very beginning level--don’t you think so? V: Uh-huh, yes. I read it like, if he solved the fingering problem, then he would become a great organist and a composer. Which is obviously...not enough. A: Yes, because I think fingering is only one small part of performance. V: Mhm. What about pedaling, right? A: True. True, and all other things, you know; and if you want to become a composer, you need to know theory very well, too. To be able to analyze pieces. V: Let’s talk a little bit about fingering, right? A: Mhm, mhm. V: How to solve this fingering problem, if he doesn’t use our fingering and pedaling scores. A: Well, when making your own fingering, you need to know what piece you are working on, and the style it is written in--if it’s a Baroque piece, or if it’s a Romantic piece, or if it’s a modern piece. And you finger it accordingly. And we have talked about those basic principles of fingering many times already. V: Mhm. And since Osei wasn’t listening, we can repeat that again, right? So, let’s say, for Baroque fingering, what you must avoid is playing with finger substitutions, glissandos, things like that. Avoid using thumb whenever possible, right? If it’s maybe… A: On the black keys--on the upper keys. V: Yes. If it’s a chromatic music, especially from the 18th century, then avoiding the thumb is not really possible most of the time. I guess using those 3 main fingers--2, 3, and 4--are very important in early music, right? In both hands. What about, let’s say, modern music, or legato style music? A: Well, you can use finger substitution, and glissandos… V: But not always, right? A: Not always. It depends on what the articulation needs. If you have to play legato, then yes--you will use all those techniques. V: If you play frequently scales and arpeggios, you can figure out most of the modern fingering, too, without any glissandos and substitutions. A: True, true. V: But substitutions and glissandos come in handy when you are playing more than one voice in one hand. A: And that very often happens in the 19th century and later music. V: Right. Is it ok to use the same finger in some of the middle voices, when it’s not possible to play legato? A: Well, yes--you have to do that quite often. V: Mhm. Basically you lift up a little bit; and since the audience will still hear the upper voice and the bottom voice, it’s not a big deal. A: Well, actually, sometimes it’s even possible to connect--to play legato--2 notes with your thumb. V: Ah yes. Thumb glissandos, yes. A: That’s right. V: So that’s basically the main principles of playing with the modern music with efficient fingering, right? What about his dream of becoming a great organist and a composer? Can we help him a little bit? What would be the first step? A: Well, of course to practice a lot. V: Sit down on the organ bench as often as he can, maybe every day, right? A: Sure. If you want to become a great organist, you have to practice every day. V: How long--for how long? A: Well, at least 2, or even 3 or 4 hours. V: Let’s say 4 hours. For a great organist, you have to practice for 4 hours. 2 hours in the morning, 2 hours in the afternoon. With breaks, of course; don’t hurt yourself. Don’t hurt your back. And you have to walk around, drink a glass of water, and stretch every 30 min or so. But since Osei has a lofty goal to become a great organist and a composer, I think pushing yourself a little bit more and playing 4 hours a day is doable. A: Yes; and about becoming a composer, too, I think it’s important to understand that composition is probably the highest level of all musical creativity. I would say that improvisation might be a little bit higher… V: Higher, yes, I was going for that. Why higher, Ausra? A: Because then you are composing right on the spot. V: Oh, thank you. You’re sort of developing further the great idea… A: But so, you know, to become a composer, you need to understand music theory, music harmony, musical analysis very well, too; you need to have...to know different musical styles; you have to know a little bit of musical history, too. And then, after studying other composers’ styles, other musical styles, you need to develop your own style. V: Mhm. Does it come naturally or do you have to force yourself? A: Well...I think both ways. For some it might come naturally, but for some I think… V: Do you think Bach...Let’s talk about Bach. Do you think when he was creating music in the 18th century, would he think, “Oh, how can I become original?” A: Well, I think each great composer started by studying other composers’ works. V: Copying them! A: Yes, copying them. Like Bach, for example, when he lived with his brother, at night in secret he would write pieces by Johann Pachelbel. V: Right. And at first his compositions were similar to Pachelbel’s. A: Sure. And then, remember that story when he went on foot throughout Germany to Lübeck listen to Buxtehude and to Reincken in Hamburg. So obviously he was learning from them as well. V: Mhm. And when he was living in those parts, he learned from them, in Nuremberg. A: True. And since you can find all those Italian and French influences in his music (and obviously German influence--various German influences, because Pachelbel lived in once part of Germany where music was so much different from, let’s say, Northern Germany), so he studied all those influences, and you can find all of them in his music. Of course, he sort of remade them: reworked them, recycled them, and used them in his own unique way. And of course, you also need to mention that he knew stile antico very well. V: Which is Renaissance style. A: Which is Renaissance, so obviously he knew works, probably, by such great masters as Palestrina. V: Mhm. A: And di Lasso. V: And let’s say, Frescobaldi. A: True, true. V: Mhm. Yes. You know, you mentioned a great idea, that he combined several ideas into one style--German, Italian, French--and made it his own, this combination that we know as a mature Bach style. As a mature Baroque style, even, right? So, a person like Osei could first copy some music of his favorite composers, study them, get curious about them, analyze them, and maybe create something really similar that these composers did at first. But once he gets better at that--once it becomes boring--he could combine a few elements into one piece, a few stylistic elements into one composition. That’s how we become original, right? Not copying one, but stealing from many composers. A: That’s right. And since Bach lived in the 18th century, and we live in the 21st century, we have much more things to study from, because the music history is already much richer and longer compared to the 18th century. V: Uh-huh, so we have so much material that the old masters didn’t have before. A: That’s right. V: That’s great. And this is such a lofty goal, right? To become a great composer and organist? Do you think that Osei could start composing right away, even if he doesn’t know so much about organ history or music theory, harmony, other composers’ stylistic elements? Could he do that today? A: Well, I wouldn’t do that, if I would be him. V: Why? A: Well...Would you? V: It’s not forbidden to start composing, right? It wouldn’t be great; and he has to, so to say, fail a lot at first, right? And a little bit later, he will find out a few breakthroughs. And that’s okay, right? You have to start small. That’s what I would do. A: Well, you know, the scary thing for me is that there are many many young people nowadays who imagine that they are great composers already. V: Mhm. A: But they cannot themselves either play nor understand music. And I don’t know how they compose. Probably they are just using digital software. V: Mhm. A: To help them to do it. And I wouldn’t want to play a piece written by such a composer. V: Mhm. A: Because in order for me to take a composition of somebody and to play it, I need to respect that composer. V: Mhm. That’s a great idea, because we can compare composing to writing. And there are so many writers who create novels, and a lot of novels are not good. Simply bad writing. So the first rule in writing, probably, is “Write a book you want to read yourself.” Right? If you are not reading that book yourself, if you wouldn’t recommend it to anybody else, that kind of style, then it’s not a good book. So with composition, probably, it’s the same. You have to compose music you want to play yourself. A: True. And in order to do that, you need to be able to play the instrument. V: Mhm. A: And if you are writing for organ, you need to know about it. V: Mhm. So, becoming a great organist and composer--actually, it’s connected, right? It’s two sides of one coin. You cannot become a great organist if you’re not actually creating; and you can’t create well if you’re not playing the instrument, if you’re not, basically, familiar with the vast variety of organ repertoire which came before. Right? So tell, Ausra, your final advice to Osei? A: Well, so just you know, keep going, and keep motivating yourself. V: Mhm. A: And have a little goal for every day… V: Mhm. A: ...Knowing that it will finally lead you to becoming a great organist and composer. V: And my advice would be, probably, start small and have the goal of becoming a bad composer first. Right? Create bad music first, but lots of it; and then little by little, if you create lots, maybe a thousand compositions that are bad, maybe one or two will be good, you know? And then in 20 years, you’ll become a great composer. A: Well, yes, for some composers it was enough to make one excellent piece that they would be remembered for forever. V: Right. So it’s a long life, and hopefully you can create something new every day. And it doesn’t have to be perfect, right? Because perfection is the killer of creativity. Thank you guys, this was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: Please send us more of your questions; we love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice… A: Miracles happen.

This blog/podcast is supported by Total Organist - the most comprehensive organ training program online. It has hundreds of courses, coaching and practice materials for every area of organ playing, thousands of instructional videos and PDF's. You will NOT find more value anywhere else online...

Total Organist helps you to master any piece, perfect your technique, develop your sight-reading skills, and improvise or compose your own music and much much more... Sign up and begin your training today. And of course, you will get the 1st month free too. You can cancel anytime. Join 80+ other Total Organist students here Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start Episode 224 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. This question was sent by Steven and he writes: It would be an extremely interesting subject some time for a podcast, if you and Ausra might consider discussing what the elements of a good free theme and a good fugue theme are, as regards development. All the best, Steven V: So Steven he frequently composes various organ compositions and he likes to create preludes and fugues out of free themes not based on a chorale melody and he wants basically to know if there are any themes that are unsuitable for musical development or are any themes suited better than others. So of course we could take examples of masterworks by various composers, right Ausra? A: True, yes there is so much music written. V: And when you play those pieces Ausra do you notice that those melodies have something in common. A: (Laughs) Of course all the musical melodies we have something in common and that’s the music notation and intervals, certain intervals. V: So which intervals basically are not very good for developing a theme in a prelude or a fugue. Perhaps intervals which are difficult to sing? A: Yes, I think big leaps maybe are not so suitable and not so common although you could encounter them as well. But in general when creating a subject or a theme for your piece you need to know how will it sound if you will invert it. Because especially in fugues the technique you use is called invertible counterpoint. V: Exactly. For example right now we are looking at Prelude and Fugue in G Major by Bach, BWV 541. And the fugue lends itself very well for the canon because it has intervals of ascending fourths and ascending sixths and when you do that at a certain interval you get a nice strata so every good fugue usually has a strata, but not always, but composers tend to seek out elements of their theme that would be suitable for that. A: Sure. Right now I’m thinking about the C Major fugue from Well Tempered Clavier, Part 1. It has a very nice steata at the end of it. V: And basically this is a scholastic fugue because in almost every measure you can find appearances of the theme and in various ways as you say, inverted, and in canon and composer created this fugue specifically out of this theme and every measure is based on the theme basically. So whatever you do in your fugue you should always think about the theme and of course countersubject. A: True. V: Is countersubject important Ausra? A: Well, it’s of course important but probably not as much as the theme because what you do with your theme that you actually need to have it throughout the piece. V: Um-hmm. A: And whatever changes you do we can not go very far from the theme. You could do it augmented or diminished. V: Um-hmm. A: In long note values or in the short note values but basically you still keep the same interval structure. But what you can do with the countersubject, actually in some fugues the countersubject is kept throughout the piece and actually that’s a very high level of polyphonic composition if you keep the countersubject the same throughout the piece. But in some pieces it changes all the time, slightly or even more. V: They say that’s it’s easier to compose a fugue with changing countersubject that with fixed countersubject. A: True. I believe it. V: And we could analyze a theme or a countersubject based on at least three elements, melody, harmony, and rhythm. And every melody, every subject, and countersubject should have those melody rhythmic elements and harmonic elements well fixed and well developed and encoded basically so that you could develop your piece entirely based on those three melodies. Let’s say we take a look at the theme of the G Major Fugue by Bach. And the melody it has nice intervals, right? And it has a nice range. It doesn’t exceed an octave. That’s usually. A: Yes, that’s usually the case even I would say that most of the fugues are, the theme are not exceed more that a sixth interval. V: Except in a minor mode they allow a diminished seventh. A: True. V: So then here in G Major Fugue we have a range from D to B, this is a major sixth, that’s about normal. A: Yes. V: If you have just a few notes of range like a minor third it’s a little too few notes, too few melodic intervals. A: True, then you will not have a chance to develop them. V: Maybe. If that’s the case your countersubject should be contrasting with wider leaps. A: True. V: So then of course melody should be singable. Basically you need to write those intervals and sing yourself. Can you sing that fugal theme yourself. That’s another reason we try to avoid augmented intervals. A: Yeah. V: And wide leaps above major sixth let’s say. What about the rhythm. What do you see here Ausra? A: Well most of fugue themes consist of eighth notes, quarter notes, some sixteenth notes. V: So whatever meter you decide to create you have to use the values that are suitable for that meter. A: True. V: Well some composers choose to use like triplets, special duplets, as they say, which is quite uncommon because then you mix duplets with triplets and in a fugal theme it’s not very often seen. A: True. I think it’s better to stick with common values such as eighth notes, quarter notes, sixteenth notes. V: Because with the countersubject if you do let’s say sixteenth notes or eighth notes and with the subject you do triplets you have a hard time of mixing them together as a performer. A: True. V: Um-hmm. Then it’s maybe better to change the meter altogether and write in a six, eight meter. What about the harmony? Of course a fugal theme is a melody for one voice. Of course we have sometimes double fugues where two voices enter subsequently one after another and then some harmony can be traced out of those two voices but it’s quite uncommon. If you are just starting writing fugues of course we recommend sticking to one theme. A: That’s right. But already I think you know that most of the Bach fugues could be analyzed in terms of harmonical chords. V: Definitely. Let’s say we have the stronger beats in 4-4 meter every two beats, we have a rather strong emphasis on the note and here we have to change the harmonies and let’s see how Bach does. The first measure has D and G so on D you could harmonize as the dominant chord of G Major, on G you could harmonize what? A: Tonic. V: Tonic. Then the second measure starts with the suspension basically F# is the main note. A: Yes, and you have the dominant again. That’s very common for opening stuff, any piece. Then you need to establish key and you use dominant, tonic. V: Dominant, tonic, dominant, tonic. And then the second chord is on the note D which is also a tonic obviously. A: Yes. There you also have some A note, this would be something of the dominant, yes. So basically this would be juxtaposition of dominant and tonic throughout the subject. V: Yes, and the second half of the third measure has noted G. We could harmonize it as the tonic also. And the fourth measure begins with the dominant function ending of the fugal theme. So in every measure we should have at least two chords. And sometimes sub-dominant too. Tonic, dominant, and subdominant they work well and remember we could have inversions, not only root position chords but inversions. So when you write a theme for yourself on a sheet of paper maybe write on two staffs on the higher staff you could write the theme and on the lower staff you could add the bass line. And this bass line might be the basis for your countersubject. A: True. V: Speaking of which, what is the difference between subject and countersubject right here in the second line. Are they similar or contrasting? A: I’m looking at it right now. I’m trying to decide. V: When the theme has eighth notes what does the countersubject have? A: Of course the countersubject has smaller note values. That’s very typical for countersubject. V: When the theme subject has smaller note values… A: Countersubject has the longer note values. V: Um-hmm. And vice-versa. Basically it’s a dialog between two voices. A: True. V: One is speaking and another is listening. A: Yes, because if everybody would try to speak at the same time you would have chaos. V: Um-hmm. And since we didn’t have any tied over notes or just one syncopation in the theme there are syncopations in the countersubject as well. More of them, right? To make an interesting rhythmic element. A: That’s right. V: But if we look at the melodic element of the countersubject it has this wide leap upwards an octave. Ausra, what does the subject do at that moment? It goes... A: down. V: Down. It’s an opposite direction. Always try to create a contrasting motion between two voices and that’s very good for making two voices independent. A: But you could also have parallel motion for example when the third voice will come in. And you will have the theme, the countersubject, and the third voice. V: Um-hmm. And by the way if you have three voices later on you could easily create a fugue with two countersubjects which are fixed and they are interchangeably connected and they could be inverted and used in various combinations and in various voices. This is called permutation fugue where soprano suddenly becomes the bass, alto becomes soprano, or the bass becomes alto or soprano. Any number of combinations. But then there is one caveat to avoid. What is the least used inversion of the tonic chord Ausra? A: 4-6 chord. V: Uh-huh. So we have to check that there is no such intervals as the fourth above the bass or the fifth above the bass because in inversion they would create fourths or fifths. Fifth in itself is good but fourth when you invert makes 6-4 chord so what do we use instead? A: 6th chord. V: And basically intervals of the thirds and sixths if you want to use this invertible counterpoint. A: And actually you know if you really want to compose fugues you have to study the fugues written by great composers and most famous collections probably would be Well Tempered Clavier by J.S. Bach, then probably if you want to study more modern style you could study Paul Hindemith’s Ludus Tonalis. V: And don’t forget Art of Fugue. A: Yes, Art of Fugue of course but that might be too complex maybe, don’t you think so? And another composer probably would be Dmitri Shostakovich, also his 24 Preludes and Fugues. V: In a modern style. A: Yes, in a modern style. I think he also got his inspiration from J. S. Bach. V: Um-hmm. That’s right. If I remember correctly Prelude and Fugue in C Major doesn’t have any accidentals at all. A: I think so, yes. V: White keys only. So that’s the start right? So not every melody is suited for fugal development. A: Maybe you know if it’s hard for you to create your own theme for a beginner you could pick some of these composers themes and try to create fugues. V: Um-hmm. What about prelude? Prelude of course it’s another story. Maybe we could leave it for another conversation in next podcast, right? Maybe we should start it with the prelude but since we started with the fugue now prelude comes later. OK guys, this was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: And remember when you practice… A: Miracles happen.

Vidas: Let’s start Episode 76 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. And today’s question was sent by Paul. He writes, “I want to be able to take any music and create an arrangement which would be possible for me to play without automatic or electronic tricks, and yet would be found interesting and fun for whoever should hear it.” Ausra, is it a question about arranging music? Or improvising music? What do you think?

Ausra: Actually, I’m not sure I understood this question right. Vidas: In my mind, I think Paul means that he wants to make a version of a piece that was originally composed not for organ. Like arranging for organ. Ausra: Transcription? Vidas: Like transcription, yeah. Ausra: Could be. Vidas: So, let’s talk about the best way to make organ transcriptions. We have made a few, right, like the famous Jesu Joy of Man’s Desiring by Bach? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: And we’ve played together, and alone. I think we have to understand that the organ, with two hands and one pedal line, cannot really play everything that, let’s say, orchestra can play, or even pianist with large leaps and octaves can achieve. Even choir or double choirs or certain instrumental ensembles...Do you think that there are certain voices that we could omit, and certain voices that we could keep? Ausra: Definitely you have to keep, of course, the melody, because it’s the most well-known; but with other voices, I think you have to omit something. Vidas: What is the second most-important voice? Ausra: The bass. Vidas: So you have to have at least two voices in your arrangements: one for RH, one for LH. What if you have pedals, and you can play the bass with the pedals? Ausra: Yes, that’s right, that would be the best, I think Vidas: What could your LH play, then? Ausra: Some sort of accompaniment, to fill in the harmony. Vidas: One or two voices? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: To keep the chords complete? Ausra: That’s right. Vidas: So what I mean is, if you take a vertical line (not a horizontal line, but a vertical line--one beat, right?), and you play RH and pedals together at the same time, and you see what is sounding, let’s say in the RH there is for example C, and (in the pedals) is also a C. So you have to fill in some harmony. So think, if it’s a C Major chord, what could be filled in? E and G, probably. Ausra: Yes, that’s right. Vidas: What is more important, E or G, in C Major? Ausra: Of course E. Vidas: Why? Ausra: Because it gives you the understanding that it’s a major chord. If you would omit E and add G, then what’s that? You wouldn’t be able to hear that it’s a major chord. Vidas: So from G to E, what is this interval? Major third, right? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: And from C to G, what is that? Ausra: That’s a fifth. Vidas: A perfect fifth. And can you discover that it’s a major chord from the third alone? Ausra: Of course. Vidas: And not from the fifth? Ausra: Definitely. Study the cadences. Most of them at the end have incomplete tonic with a third but without a fifth. Vidas: So guys, if you want to limit yourself to three voices, always have a third in your chord, right? Ausra: That’s right. And the same with like, four-voice chords, like seventhchords. You always omit the fifth, if you have to omit something. Vidas: Excellent. Can your melody, by the way, be in the LH, in the tenor range? Ausra: Could be, but that way I think it would be much harder to play. Vidas: And then you would need an extra solo stop, right? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: On a separate manual. Ausra: And because I think it was Paul who asked about a coordination problem in the last question--the question that we answered before--so I would not suggest him to put the melody in the LH. It might add extra problems. Vidas: Could be. But for other people--or for Paul in the future, when he is advanced enough--that’s another way to arrange: in the tenor. Ausra: And of course, the melody can be in the bass, too. Vidas: But then you have another problem: about harmonization, right? Because then, if you transfer your melody from soprano to bass, your soprano becomes the foundation of the harmony; and then the chords that would have fitted earlier will not necessarily work, right? Ausra: But I think you always have to see what kind of piece you are arranging for organ, and to look what it is in the original. Vidas: Well, exactly, because maybe the original has another bass line. Ausra: That’s true. Vidas: Right. Good, guys. Please experiment with your arrangements, and send more of your questions to us. We love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice… Ausra: Miracles happen. |

DON'T MISS A THING! FREE UPDATES BY EMAIL.Thank you!You have successfully joined our subscriber list.  Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas

Authors

Drs. Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene Organists of Vilnius University , creators of Secrets of Organ Playing. Our Hauptwerk Setup:

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

This site participates in the Amazon, Thomann and other affiliate programs, the proceeds of which keep it free for anyone to read.

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed