|

We're so delighted to be able to start a new podcast #AskVidasAndAusra!

We'll do a limited number of short audio episodes and share them on this blog. Our goal here is to help our most valued subscribers, people who support the most what we do. Sometimes we'll answer questions together, sometimes separately. So today's question was sent by Jan who is taking advantage of the free trial of our Total Organist membership program. Here's what she wrote: "Dear Vidas and Ausra, My most pressing question is... how can I keep a steady tempo? My teacher tells me every time I have a lesson, in every piece that I play, that I am playing with multiple tempos. I think that I am playing with a steady beat but when I test with the metronome, I am all over the place. I am stuck as to how to fix this problem. At present I do some of my practice with a metronome. I am not a beginner. This is frustrating and disheartening. Thank you for your help." Listen to what we had to say this morning about it while doing our 10000 step practice in the woods. IMPORTANT: If you would like us to answer your questions for #AskVidasAndAusra and share on this blog, please post them as comments and not through email. Make sure you add a hashtag #AskVidasAndAusra because otherwise your question might get lost among many other comments people leave. With the hashtag #AskVidasAndAusra we'll know exactly you want us to answer them in the correct place. We are looking forward to helping you reach your dreams. Are you excited as much as we are? You should be. And remember... When you practice, miracles happen. Vidas and Ausra (Get free updates of new posts here) TRANSCRIPT Vidas: Hello guys. This is Vidas. Ausra: And Ausra. Vidas: And, this is episode number one of our new show, #AskVidasAndAusra. We're very excited and we're walking here though the woods now in the morning, and you can hear the birds singing, correct? How are you feeling today, Ausra? Ausra: I'm fine. What about you? Vidas: Yeah, I think I'm quite ready to answer people’s questions. We received four questions so far, and we have four episodes lined up for you. And, today we're going to basically answer the first question that came to us, and it was written by Jan, and it was wonderful question, I'm trying to read now. And, she writes things about playing with a steady tempo. Here is "How can I keep a steady tempo?" That's her question, and I will explain. She writes "My teacher tells me every time I have a lesson, in every piece that I play, that I am playing with multiple tempos. I think that I am playing with a steady beat but when I test with the metronome, I am all over the place. I am stuck as to how to fix this problem at present. I do some of my practice with a metronome." And, she writes that she's not a beginner and that's, of course, frustrating and disheartening. So, Ausra, do you think that this kind of problem is common among organists? Ausra: Yes, I think this problem is common among all musicians, not only organists, because even pianists or violinists can have the same problem. Vidas: That's true. Do you remember the time when you had this problem? Because, it was probably a very long time ago. Ausra: Yes, I remember one time, when I was working on Bach’s C Minor Prelude and Fugue. Vidas: BWV 546? Ausra: Yes, I had that problem in the prelude. Vidas: And, especially in that episode, when the eighth notes change with the triplets, right? Ausra: Yes, that's right. Vidas: So, what helped you that moment to solve this problem? Ausra: I don't remember exactly, but in general I thought a lot about it. Because then, later in life I returned to that piece. I just could not understand how I could play so badly at that time, so arhythmically. Vidas: Yeah and our professor, we were studying by the same professor Leopoldas Digrys, I think at the time. And, he was very mad, actually, because of this spat episode, and- Ausra: I think he just kept shouting at me and I think I was scared of him, that I could not play it correctly, so never shout at your students. Vidas: That's rule number one. Even if you are frustrated with your students, you should not shout at them, right? But, of course, back to the question. Imagine Jan is having the same thing like you had back, maybe some 20 years ago, when you first started playing the organ. Or, other people around the world, also facing the same problem. What do you think, Ausra, keeping the steady tempo might be possible if a person plays with the metronome all the time? Ausra: Actually, metronome is only to check your tempo, what tempo you should be. But, it's not a good tool to practice with it all the time, because finally when you will have to perform this piece, during exam or during a recital, you will not have a metronome. Metronome doesn't let you to show the structure of a piece, actually, because keeping the steady tempo is not the only thing you have to do in the piece. Because, there are other structural moments, cadences where you might have to slow down a little bit, or fasten up a little bit to show the structure of a piece. To play like a human being, not like a robot. And that’s, I think, why a metronome is not such a great idea to practice with it all the time. Maybe time after time, you can do it, but not all the time, and I don't think that metronome will solve this problem of playing in steady tempo. Vidas: Hey, do you remember we have in Unda Maris studio, this wonderful lady who is practicing with us for six years now I think, from the beginning. And, she has the goal to master all the eight little Preludes and Fugues, right? And, she has mastered, I think five or six of them by now. Just a couple of them left, right? And she is really determined, but one of her major problems is really keeping the steady tempo in pieces, right? So, remember what we suggested to her too? I think to count out loud and sub-divide the beats. If, imagine she plays the piece in 4/4 meter. I think we said counting out loud those four beats, four quarter notes, and doing this loudly, counting out loud. Because, as Jan probably experiences, because a lot of people think they are playing in a steady tempo, and even counting naturally and evenly. But, it appears that when they listen to the recording, it's not true, right? Or, when somebody else is listening from the side. The only possible way that I found, is really to force yourself to count out loud steadily. Would you agree, Ausra? Ausra: Yes, it's very helpful, but you have to do it loudly. Or, to do it mechanically with your mouth, with your tongue, just sub-divide. For example, sixteenths, feel them, because otherwise if you will do it only in your head, it doesn't happen. It will not work. Vidas: Right, because you think you are counting steadily inside of you, right? In your mind. But, your music can be all over the place. Ausra: That's what I did when I learned Icarus by Jean Guillou. I sub-divided all the time, the smallest values, with my tongue. It actually really helped, because it's a tricky piece to play it technically and to play it rhythmically correctly, in a very fast tempo. So, that's what I did to beginning of learning that piece. I would just sub-divide all the time, and even do it in my performance. At a final stage, sometimes I would sub-divide at least some spots. Just to keep it in good tempo and rhythmically, correctly. Vidas: So, then probably the shortcut to this, for Jan and others, to master the piece at the level that she could really play fluently, in order to concentrate on the counting, right? Ausra: Sure, because another problem why the tempo can change. It might be that ... Although, she is not a beginner, yes? At the keyboard, but still, all of us have some harder spots in the piece and some easier spots, and sometimes when you get to the harder spot, you start to slow down. But, when you know you are playing an easier place, let see, where the sequences are going all the time, you sort of starting to go faster and faster because it's easier. You really need to make sure that places where you slow down are not technically harder than other places. Vidas: Right. All of the episodes in your piece, in your mind, should be of equal level of complexity. Although, some episodes might have 16th notes, or even 32nd notes, or triplets, or syncopation, right? But, you have to master those episodes so well that they should be as easy as playing quarter notes, let's say, or half notes in other spots, right? So, wonderful. I think Jan can now try this technique, and other people can try this technique. By the way, Jan is our Total Organist student and really tries to perfect her organ playing through our study programs and coaching, training materials, which also a lot of people have found tremendously valuable. And, right now we have this 30 day trial period, where you can really subscribe for free and try out all the material without any payment for 30 days, for one month. And, if you like it, you can decide to keep subscribing and if you decide it's not for you, you can cancel before the month ends. So, I think we will go on with our day to day things right now. As we are walking through the woods, I think the birds are singing quite loud, and mosquitoes are biting in my legs now, because I'm wearing shorts and my feet are basically uncovered. And, it's a really beautiful view, very green, wonderful morning. Ausra, what piece will you be practicing today, by the way? Ausra: I think I finally will learn the Piece d'Orgue. Vidas: Piece d'Orgue, right? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: It's a fantastic piece. Do you need my fingerings that I am preparing for this? Ausra: I think it will be helpful. Vidas: And pedalings right? Ausra: Yes, especially nice that I don't have to write them down myself. Vidas: Right, right, because sometimes people don't like to write fingerings because it's a lot of work to do this, but if somebody can provide the fingerings and pedalings for you, that saves maybe 30 hours of work for some people, right? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: Wonderful. So guys, this was Vidas and Ausra talking to you from the woods of this vicinity of Vilnius, Lithuania. And, if you like this episode and would like to ask us more questions related to any area of organ playing, basically, we'd like to help you achieve your dreams. So, click on the comments section of this post and send us your question. But, makes sure we find this question, because a lot of comments we get is not related to our podcast, right? But, basically to anything else. So, if you want us to find and answer your questions directly on this #AskVidasAndAusra podcast, right? So, make sure you include hashtag, #AskVidasAndAusra and post it on the comment section of this blog. So, thank you so much, guys. This is Vidas. Ausra: And Ausra. Vidas: And, I hope you will have a tremendous success in your practice today. Ausra: Bye.

Comments

By Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene (get free updates of new posts here)

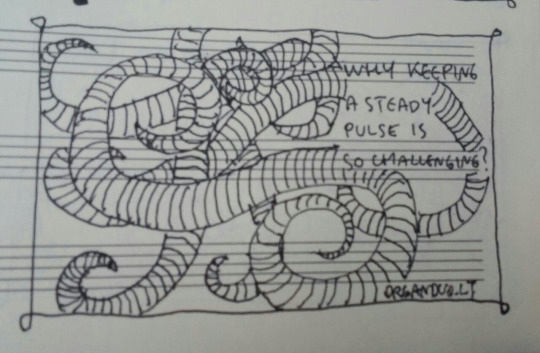

One of the most common mistakes beginner organists make is to keep the uneven tempo in their pieces. Where it's easy, they speed up, where it's difficult, they slow down. No matter how hard they try to keep the steady tempo - it's just too overwhelming. Here's the trick which CONSTANTLY helps me to be precise in my playing: In rhythmically difficult places I keep counting and subdividing the beats down to the smallest rhythmical value of the piece. Let's say, you're playing BWV 554 and some places of this prelude and fugue in D minor are more difficult than others. What beginner organists often do, they slow down in the middle of the fugue where the pedal part comes in. They do this towards the end when the texture gets more complex. Since the smallest rhythmical unit here is the 16th notes I recommend counting in these note values. In your mind keep a steady flow of sixteenths. Then you won't have to worry about uneven tempo. By Vidas Pinkevicius

My organ students often have a trouble keeping a steady tempo. They either speed up or slow down depending on the situation. Keeping a steady tempo has a lot to do with keeping a steady pulse. How do you do it? It's simple: Count the beats in a measure out loud. That's where the students start to argue: "Can I just count in my mind?" "Yes, you can but you won't be able to tell whether your counting is even." "But it's hard to say the numbers so you could hear them and play at the same time." Yes, it is but do it until your sense of pulse improves and you won't regret it." There is something magical about being able to listen to your own voice. It's like observing another you which turns you into your own guinea pig. Yesterday one of my organ students at National M.K. Čiurlionis school of art, Eglė participated in the Festival of Ciurlionis piano and organ music where she played the Fugue in C# minor. This was a good overall performance but I want to point out a particularly peculiar episode that happened during her performance. I'm sure many of my readers will know what I'm talking about because this experience concerns us all (myself included).

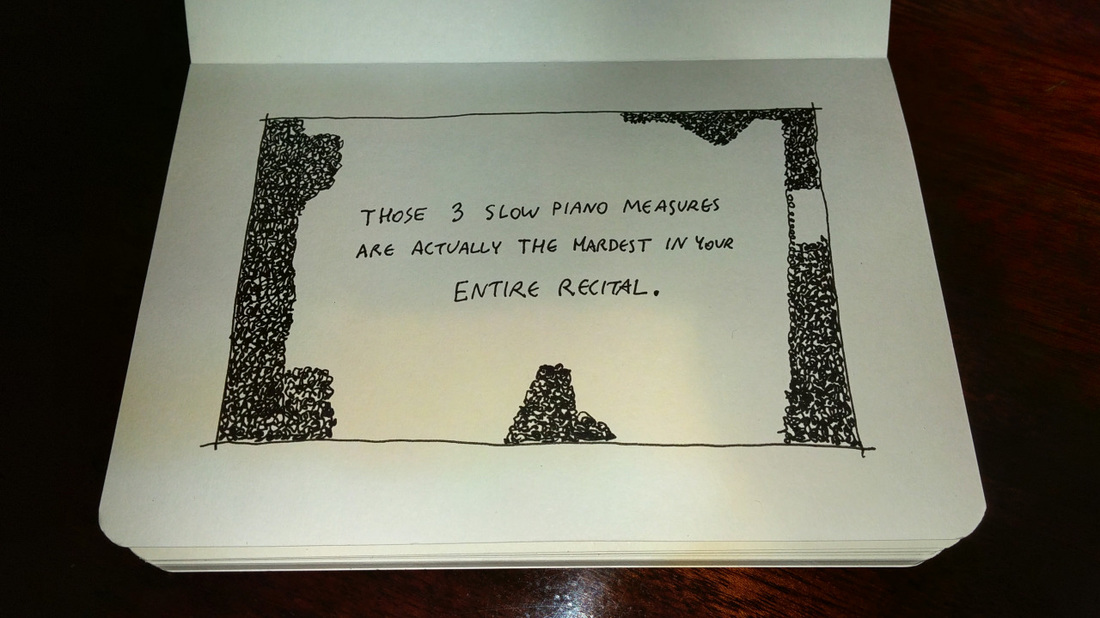

This is a piece which starts with a subject performed with a soft Flute 8' registration in a slow tempo (here is a video of it I played at Vilnius University Saint John's church). As the fugue unfolds, the two hands start to play with Flutes 8' and 4' on a different manual. Gradually the tempo, tension, and dynamic level begins to increase but at Flute 8' and 4' episode the music is still gentle and slow enough. So even though it was technically quite an easy spot, Eglė's fingers slipped in a couple of places. This probably wasn't noticeable to the listeners out in the room but since I assisted her with page turns and stop changes, I knew something was going on with her mentally. Something that happens to us when we know that it's easy, when we know that the finish line is near, when we know that the battle is almost over. And then we slip. And then we play the wrong notes. And then we lose focus. And then we panic. And then we blame ourselves. Luckily Eglė is an experienced enough to know better. Those couple of slips didn't throw her off balance not a bit. She finished strong as if nothing happened. In the words of the legendary American organist Marilyn Mason, "your recital is not over, until you are in the parking lot". The trick is to keep focusing on the current measure you are playing no matter what. Karen asks about the concert tempo in Wir glauben all' an einen Gott, BWV 680 from the Clavierubung III by J.S. Bach. She has listened to various recordings and studied the information she has about this piece, but the question about the concert tempo remains unclear to her. She writes that Hermann Keller recommends eighth note at 138, but recordings she has listened to seem to have anything from eighth note at 100 to quarter note at 120.

This is a great and very important question because in many compositions of the Baroque period composers didn't leave any precise tempo indications. When you don't have a tempo suggestion written in (like Adagio, Moderato, Allegro etc.) nor metronome markings, how are you supposed to figure out the concert tempo at which to perform in public? In order to answer this question about many pieces from the Baroque period (like this chorale prelude), we have to take into consideration these 7 things: meter, acoustics, mechanics of the organ, your technique, hearing, singing style, and breathing. 1. Meter of the piece. Generally speaking (but not always), the smaller the beat value in the composition, the faster the tempo should be. For example, 3/8 is faster than 3/4. Count the beats and pay attention to the alternation of the strong and weak beats. This will be helpful in slow pieces. 2. Acoustics of the room. The space that you are playing in will be one of the major factors in determining the speed of this piece. If you play in your practice room or at home, you can perform much faster than in a cathedral or church with huge reverberation. 3. Mechanics of the organ. The type of organ action also determines the tempo of this piece. In general, if you are performing on the tracker or mechanical action instrument, try to play a bit slower because of the action. On the other hand, if you are playing on the electro-pneumatic or electronic organ you can play much faster. 4. Your technique. If your technique is not developed enough, naturally you will not be able to play very fast. In this case, choose a tempo on the slower side of the spectrum which you would be comfortable with. 5. Your hearing. Try to listen attentively to each harmonic turn and dissonance. This is particularly challenging to organists who have great technique and want to show off their virtuosity. Remember that in the Baroque music, we are showing off the music and the musical story and not ourselves. 6. Singing style. Try to retain the cantabile style in the performance of the piece. Even the fast pieces should have this character. 7. Your breathing. Try to sing with full voice the phrases with one breath. This will help you choose the tempo which would not be too slow for the musical flow. Keep in mind the above 7 tips when you try to decide what kind of concert tempo is best suitable for you and your piece. Since we all are different and play in different spaces with different organs, the tempo may fluctuate quite a bit. Margaret writes that her dream for playing organ is to play faster and without mistakes. For her the main obstacles which prevent her reaching this dream are the difficulty in reaching a faster tempo, eliminating mistakes and memorization of the score.

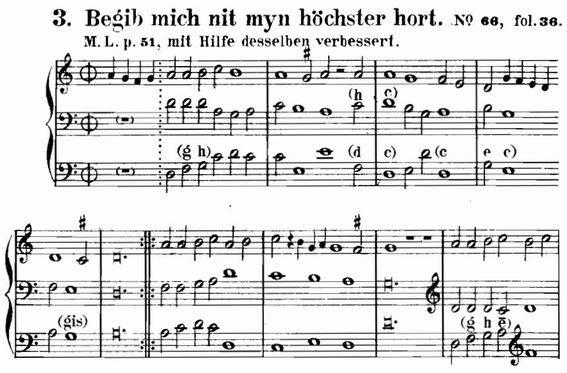

The dream that Margaret has is common to many organists. But it's not so easy to make it a reality. So often people can only play rather slow music and when they try to play faster, lots of mistakes appear. This is frustrating. If you experience such challenges as Margaret, you have to understand that it's better to play slower than with many mistakes. Therefore, choose the tempo according to your level of ability. By repeatedly practicing very slowly and reducing the texture to single voice and various voice combinations, you will be able to eliminate mistakes and reach the level when you can play rather slowly but fluently. If you want to play faster, perhaps you need a) to work on your technique and b) to practice your pieces at the concert tempo but stopping and waiting at the smallest fragment imaginable - a quarter note. Once you can play this way until the end of the piece at least 3 times without mistakes, stop every two beats, then one measure, two measures and so on always expanding your fragments and playing the music inside the fragment at the concert tempo but stopping, waiting and preparing for the next fragment. If you want to memorize music easier, you have to develop a systematic procedure of practicing short fragments 5 times while looking at the score and 5 times from memory. Usually the longest fragment you can remember this way is one measure. As you might have already guessed, after memorizing one measure fragments, start expanding them little by little from memory. If you haven't done so, try to learn something about keys, chords, chord progressions, cadences, and modulations. This will help you understand how your piece is put together and consequently facilitate the process of memorization. Sight-reading: 3. Begib mich nit myn höchster hort (p. 26) from Buxheimer Orgelbuch (ca. 1450), a German Renaissance collection of organ music. Hymn playing: Hark, the Voice of Jesus Calling Do you feel like you can't play your organ piece fast enough? You worked in fragments and in separate parts and different part combinations diligently, right? But somehow your fast piece doesn't sound well. Is it that your technique is not strong enough?

Maybe. But it also might be something else. Maybe you need another practicing approach here. This video will help you to solve this problem and move to the next level in your organ playing. Do you notice how sometimes people speed up or slow down when playing organ? I mean, not in places when you see accelerando and ritardando markings in the score but all of a sudden, unexpectedly.

Such deviations from the steady tempo happen for a couple of reasons: 1. Change in texture and other musical elements 2. Change in difficulty level In other words, when there is nothing new in a composition, an organist may play in a steady tempo, like on autopilot. But when you see a different rhythmical figures coming up or when the texture starts to become more complex then a possibility arises for the unwanted change in tempo. Change in difficulty level is also very important - when there is an episode without pedals, we may begin to play faster and vice versa. So how do you keep a steady tempo in such situations? One of the biggest things you can do is to be aware of the pulse in the composition. For example, when the organist plays an episode in the fugue without pedals and sees a difficult pedal entrance later on, at that place he/she may be concerned about not missing the right notes in the pedals. Therefore, the thought about a steady pulse is forgotten. Being aware of the pulse is best done when counting out loud and sometimes even subdividing the beats in the measure. It's not easy to do, but if you achieve a feeling that you are playing and saying the numbers of the beats rhythmically, then your mind is really focused on the pulse. I stress the importance of saying them out loud so that you can actually hear the words "one and two and three and four and" (in 4/4 meter). Simply saying the words silently might not be sufficient. Practice this way and no matter if you play only in 2 or 6 parts, you will always perform in a steady tempo. You don't have to do this kind of exercise for long months. Whenever you catch yourself (either live or in recorded performance) deviate from the steady tempo, play a piece a few times with steadily counting out loud the beats and the results will be self-evident. NOTE: By keeping a steady tempo, I don't mean you should play without any regard to important structural points in the piece and automatize your performance. It would be very boring to listen and to play this way. P.S. Sometimes slowing down simply means that an organist can't play fluently. If that's the case, follow these tips. I few days ago I observed a student playing Bach's Two-Part Invention in C major, BWV 772. I will try to describe the issue with the tempo he was having because I think many people run into similar problems.

He seemed to speed up in easy places and slow down in more difficult ones. Easy places for him meant ascending and descending sequences and difficult ones - around cadences. I think it is logical that sequences are easier than cadences because in sequences, the music simply repeats in predetermined manner up or down. In other words, composer uses the same melodic and rhythmic idea but transposes (more or less) it from different pitches. Sometimes the sequence modulates to another key and sometimes it stays within the same key. At any rate, since there is only one idea, once you learn how to start it, the rest of it continues in a fairly straightforward and predictable manner. The cadence can be much more difficult to play because often the harmonic rhythm changes faster than anywhere else in the piece. In other words, around cadences there is too much going on musically and so the challenge is to play it in the same tempo. Now this student appearently felt quite strong during sequences and less so around cadences. Therefore his tempo fluctuated. It was especially noticeable in descending sequences when he began to play faster and faster as if he was in a race. Have you been in such situation yourself? If so, I think the best solution always is to count out loud the beats of the measure. When you are keeping track of the pulse, saying the numbers of the beats out loud prevents from speeding up or slowing down because it's too obvious. Of course, if you can't play fast enough, slow down and choose a tempo while checking the most difficult passages of your piece first. Sometimes it means you have to master them on a higher level and repeat many more times than the easier places in your composition. When you play a slow organ piece from the Baroque period and it sounds boring to the listener and lacks a sense of direction, sometimes it means that your tempo is too slow.

But what if your tempo is just right and the music still sounds boring? There are 2 things you can do here: 1. Shorten the weak beats of the measure. 2. Start counting the beats out loud. When you shorten the last beat of the measure, it naturally connects with the next measure and the music begins to flow (even in the slow tempo). When you count the beats out loud, you are aware of the meter and pulse - very important components of the piece which you should never forget. I know, it's exceedingly difficult to count out loud while performing but stick with it for a while and this trick will help the music come alive. |

DON'T MISS A THING! FREE UPDATES BY EMAIL.Thank you!You have successfully joined our subscriber list.  Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas

Authors

Drs. Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene Organists of Vilnius University , creators of Secrets of Organ Playing. Our Hauptwerk Setup:

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

This site participates in the Amazon, Thomann and other affiliate programs, the proceeds of which keep it free for anyone to read.

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed