|

For many adult organists having enough time during the day to practice the organ is perhaps one of the greatest challenges. I have written earlier about how to find time for organ playing . These tips might help you to realize that even when there is not much practice time available, playing organ is still possible. However, you will be surprised that actually organ practicing often can be done even without any organ at all. I hope people who have a very limited access to actual organ will find this article especially useful. Please read on to find out my suggestions.

Let me start by remembering recent experience I had while preparing a new, long, and challenging program for a concert of choral music at the Madeleine church in Paris. I was supposed to play organ accompaniments (many of them with an advanced organ part) and some solo organ pieces on the choir organ at that church. I was given the music quite early in advance but circumstances were such that did not have enough time to practice this repertoire. So I felt like it might be a bit of a challenge to perform it with confidence. Our concert was supposed to be on Tuesday afternoon, but I arrived at the hotel on Sunday afternoon. Because this church is very popular among tourist groups, I was not given any time to practice organ until the day of the concert. Imagine that – two and a half days without an organ right before the concert. Oh, and by the way, I played a full solo recital in my church with completely different music on Saturday the night before my trip to Paris. So I had to use my practice time wisely to be able to prepare multiple organ pieces . I am writing all this not because I want you to think that I was cool or something but just because I would like you to appreciate the seriousness of my situation. However, I was quite confident that my system of practicing will not fail me. And sure enough, the concert went well, and was well received. So if you are curious to know what method I used for practicing organ without having access to it for two and a half days - here it is: Because the bed of my hotel room was not high enough, I put a few cushions, pillows and other things that I could find on the edge of the bed. The height of it became similar to that of an organ bench. Then I pulled the table next to my bed so that I could put my music on it. I think you get the picture now: the bed became my organ bench, the table – music rack and keyboards, and the floor… the pedal board. So I sat there pretending that I played the real organ and began practicing. I imagined that the edge of the table was my keyboard and played just as I would on a real instrument. I also moved my feet visualizing the pedal keys accordingly. It was an interesting experience – the music sounded in my head. You see, it is all about visualization. They use it in sports and martial arts all the time. In boxing they call it “shadow boxing”, in karate - “kata”. The athletes don’t always practice their moves and techniques with a partner. Very often they practice on their own. They visualize their opponent or multiple opponents. The same thing applies to basketball as well. I once read about an experiment with 3 groups of people who liked shooting a basket. Before the experiment their abilities were measured. Group A was told not to practice shooting basket and forget about it for a month. Group B had to practice shooting the basket for one hour every day for one month. Finally, Group C was supposed for one hour every day to visualize the movements in great detail without actually physically shooting the basket. Their abilities were measured after one month. As you can imagine, Group A tested the same as before. Group B showed 24 percent of improvement. And here is the most interesting part – Group C showed 23 percent of improvement. That’s only one percent less than that of Group B who were physically shooting the basket for a month. I hope you can now see the power of visualization. This kind of practice not only gives you same results as you would be physically playing the real organ but also develops your mental focus abilities and inner hearing. It is important that we try to hear in our minds the music that we pretend to be playing. We don’t just go through the motions, so to speak. I am sure that practicing on the table and on the floor without mental visualization would give you some improvement, but not nearly as much as if you would practice with your inner hearing. Let’s take another real life example: About a month ago I taught a group of adult students in our organ studio. These were adults, some of them professors at the university with some piano but no organ experience. Usually the way we worked was such that one person would play exercises from our method book , I would comment, correct the mistakes, play myself to show my students how it supposed to sound. While one person was playing, others would be watching him or her and make mental notes of the mistakes, my comments so on. But one day I decided to do an experiment with them which would prove if my system was any good. And so, while one student was playing, others also were playing at the same time but on the table and on the floor. After a while I asked them to switch and another student took the place on the organ bench. Strangely enough, even though the exercise was new to her and she only practiced it on the table, she did not make any mistakes at all on the real organ. I thought maybe that was because she played only the manual part and that she will have more trouble with the pedals . After a while it was her turn to play the pedal line of that exercise on the organ and as you can feel, she did it fine, too. So you see, it works not only for the finger work but also for pedal part as well. This method of organ playing also saves time because we are not fixed to the location of the organ. Organ practice can be done anywhere where there is quiet. All you need is a table, a floor, your music, mental focus, and inner hearing. Of course, you can use this method to memorize music as well. I hope my suggestions will be useful especially to organists who have very limited practice time on the actual organ. By the way, do you want to learn to play the King of Instruments - the pipe organ? If so, download my FREE video guide: "How to Master Any Organ Composition" in which I will show you my EXACT steps, techniques, and methods that I use to practice, learn and master any piece of organ music.

Comments

One of the most common reasons why people skip practicing the organ is that they don‘t have enough time. With all other important tasks and activities during the day it seems impossible to squeeze that extra time needed for organ practice. People who work from 8 to 5 are often too exhausted to play the organ after work. Our families also require much attention. Is there any recipe or solution how to find time for organ playing? Read on to find out.

First of all, we have to set firm priorities what is most important for us during the day. If organ playing is a hobby for you, then obviously you have other responsibilities every day. These tasks need to be done first, in order to properly fulfill our duties. If you love organ playing and tend to sacrifice other more important things in your life then you should consider setting firm priorities. I am not suggesting that organ practice does not need any sacrifice at all as you will later find out; I am just saying that first things come first. Do not prioritize your family. Your family is the most important thing you have in life and they need your special attention and care. If your spouse asks for your help and you are in the middle of your organ practice, don’t say “I will help you when I am done with my organ playing”. Or if your kids ask you to look at their homework, do it right away. However, we also need to think about what we do when we work. That way we could be more productive in our work, accomplish more, and perhaps have more time for organ playing at the end of the day. Are we working seriously and staying focused on the task at hand all the time or we are reading our email, and newspapers, checking facebook, watching youtube videos during our work day? All of this takes precious time. I may say, “It will just take a few minutes and I’ll be done”, but in reality I even won’t notice how I may spend 30 minutes or more doing things that are not necessary. You see, these 30 minutes can be all you need for your organ practice after work. Some people work at evenings so they could practice organ in the morning. What about playing organ on weekends? Sure you could play more on Saturdays and Sundays. Usually our weekends are not that full of activities and we may try to practice even for 2 hours. That would be great. Imagine, how your organ playing would improve, if you could practice that much every weekend. You are probably wandering what is the minimum time required for organ playing? On weekdays, perhaps minimum time could be 30 minutes of wise and productive practice . You could work on your keyboard and pedal technique playing Hanon exercises , pedal scales , and sight reading for 30 minutes every evening and practice for 2 hours on weekends. This could be all you need to see constant improvement. Even if full practice time is unavailable for you, repeating for 15-20 minutes what you learned the day before could be much better than to skip practice that day altogether. Some people would rather practice in the mornings, other later in the evenings. Of course, this requires a little of sacrifice. But if you have a goal in mind, if you are trully passionate about organ, it is probobly worth it. Do whatever works best for you. Whatever time you choose for organ playing try to make it constant. Put it on your calendar. This way you will know exactly when to practice. You will have a constant time for it and you will not have to worry about how to squeeze it into your schedule every day. Just write it down. I know that we are all different and our needs are different, too. Every person has to find a special solution. But these are my personal recommendations and I hope you will find at least some of them useful. By the way, do you want to learn to play the King of Instruments - the pipe organ? If so, download my FREE video guide: "How to Master Any Organ Composition" in which I will show you my EXACT steps, techniques, and methods that I use to practice, learn and master any piece of organ music.

Many organists who fall in love with Bach’s organ music at some point may have heard about his extraordinary skills in improvisation, stories how he improvised a complex six-part fugue in front of Frederic the Great, King of Prussia or elaborate chorale fantasia which lasted almost half an hour for Jan Adam Reincken, the organist of St. Catherine church in Hamburg.

Upon remembering such accounts, I used to think that it was impossible to achieve such mastery for regular organists. However, my opinion started to change when I first heard organists like William Porter and Edoardo Belotti improvise at Gothenburg International Organ Academy (Sweden) back in 2000. These were the people who thought that everything that was composed theoretically could be improvised as well. They were especially interested in reconstructing the improvisation techniques of the 17th century. At the same Gothenburg International Organ Academy, I met Pamela Ruiter-Feenstra who taught improvisation in the style of Johann Sebastian Bach. Her deepest passion was to discover and reconstruct Bach’s improvisation pedagogy. Her discoveries were supposed to be published in the form of a book in 2001. I had a privilege of studying improvisation and organ performance under P.Ruiter-Feenstra at Eastern Michigan University for my Master’s degree. However, we had to wait for the appearance of her book about ten years. This book, „Bach and the Art of Improvisation“, (Ann Arbor, MI: CHI Press, 2011) “represents a lifetime of experience and experimentation, teaching and researching, performing and improvising”, as Joel Speerstra writes in the Foreword of this book. In this article, I will give a short review Volume One of the book „Bach and the Art of Improvisation“ by Pamela Ruiter-Feenstra (please note that Volume Two is forthcoming). Volume I is devoted to Chorale-based improvisation and consists of 7 chapters – Chapter 1: “Improvisation as Extemporaneous Composition”, Chapter 2: “Tenacity, Touch, and Fingering”, Chapter 3: “Thoroughbass and Cadences”, Chapter 4: “Chorales and Harmonization”, Chapter 5: “Counterpoint and Chorale Partitas”, Chapter 6: “Bach as Teenager: the Neumeister Collection”, and Chapter 7: “Bach at Forty-Something: Dance Suites”. Volume II will focus on improvisation of Free works and Continuo. The approach that P.Ruiter-Feenstra uses in her book is rather unique among other books on improvisation. It is not only a textbook with exercises but much more than that. The students who will be studying this book will acquire a comprehensive knowledge about various 18th century performance practice aspects, such as articulation, fingering, and pedaling etc. In Chapter 1: “Improvisation as Extemporaneous Composition”, P.Ruiter-Feenstra sets the stage for the entire book and presents what we know about Bach and learning, contexts and definition of 18th century improvisation. In addition, she writes about improvisation pedagogy of Bach’s time in this chapter. Remarkable is her approach to existing compositions, as models for improvisation and her method of improvisation pedagogy what she calls the cycle of Construction-Deconstruction-Reconstruction. In Chapter 2: “Tenacity, Touch, and Fingering”, the author introduces Bach’s mindset towards the process of learning and invention. In addition, she informs the reader about the basics of early keyboard technique, articulation, fingering, and pedaling and gives numerous exercises. She also writes about the importance of the clavichord technique for any keyboard instrument of the day: spinet, harpsichord, regal, positive, and organ. Here P.Ruiter-Fenstra gives an account of the experiment with two groups of students when teaching improvisation. Group A was taught early fingering first before commencing improvisation studies. On the other hand, Group B practiced improvisation right from the start and skipped the fingering section. The results were surprising: at first students of Group B were better than students from the other group on improvisation, but within 10 days Group A was improvising with more confidence, fluency, and sophistication that Group B. This experiment clearly shows the need to combine the studies of historical performance practice with practical improvisation. In fact, the author believes, that applying early fingering principles helps the students to achieve the fluency in improvisation. In Chapter 3: “Thoroughbass and Cadences”, P.Ruiter-Feentra introduces the principles of Bach’s thoroughbass playing as described in his “Precepts and Principles for Playing the Thoroughbass or Accompanying in Four Parts” and other sources. From this point onwards, the author’s improvisation pedagogy is based on the principles of thoroughbass. This chapter presents us also the concept of cadences with numerous examples and their applications on most popular chorales of the day. In Chapter 4: “Chorales and Harmonization”, the author shows what kind of system Bach used to harmonize the chorales. For example, instead of using the term “modulation” for excursions into different keys, P.Ruiter-Feenstra introduces the term “Mode shift” which she believes was an original procedure that Bach’s contemporaries, like Johann Gottfried Walther and Niedt used. The modulation in the Baroque period meant a completely different idea – “the manner in which a singer or instrumentalist brings out a melody”, as the author states. This is a major difference between our traditional understanding of harmony and 18th century composition and improvisation pedagogy. Based on this system, there are numerous chorales given to practice and harmonize. It is important to point out that this chapter also deals with the concept of affect, and different harmonizations of the same chorale tune according to the meaning of text. By the way, the Doctrine of Affect in the Baroque period was a theory stating that different modes, melodic, harmonic, and rhythmic ideas or figures could evoke different feelings or moods. In Chapter 5: “Counterpoint and Chorale Partitas”, the author discusses the role of counterpoint in creating chorale partitas as presented by Johann Joseph Fux. However, she admits that Bach’s system and the one that Fux used was not without differences. Nevertheless, Bach new and owned counterpoint treatise by Fux and his method of Species Counterpoint is still valid for improvising chorale partitas. In addition, the author also looks at Bach’s Two-Part Inventions from the counterpoint perspective and they serve as models for improvised inventions. Another feature which I find especially valuable is the overview and a catalogue of rhetorical figures. These melodic, rhythmic, harmonic, formal, and affective figures all have their precise names in Latin or other languages. Especially practical are tables of the two four-note and three note figures with specific names for each one. Upon memorizing and mastering these figures an improviser will acquire a great tool that he or she can use not only for chorale partitas but for improvisation of other forms as well. Chapter 6: “Bach as Teenager: the Neumeister Collection” deals with Bach’s early compositional style and gives models and techniques from this collection to improvise chorale preludes in the same manner. At the end of this chapter, the author discusses the principal stylistic features and principles of Bach’s later, and compositionally and technically more advanced chorale preludes. Such compositions are presented in the Orgelbuchlein, Schubler, and Clavierubung III collections. They too, serve here as models for improvisation. In Chapter 7: “Bach at Forty-Something: Dance Suites”, P.Ruiter-Feenstra discusses the main types of dances that were part of the traditional dance suite. She even gives an example of the French drawing of the choreography with a dance melody. When we think about dance suites we usually have free works in mind. However, the author, citing examples and models from contemporary sources introduces the idea that dances could be improvised even on a chorale melody. Therefore, she gives precise directions and steps to improvise the main dances of the period: allemande, courante, sarabande, minuet, and gigue. The models for these dances are taken from Bach’s English and French suites, and works by Buxtehude, Bohm, Duben, and Niedt. In conclusion, I believe the book “Bach and the Art of Improvisation” is indispensable for every serious student of historically-based improvisation. Not only organists, but also pianists, harpsichordists, and other keyboardists will have the benefit in studying the principles given in this book. After studying such comprehensive information, techniques, and exercises in Volume One, the true fans of improvisation will eagerly wait for the appearance of Volume Two which will focus on improvisation of interludes and cadenzas, preludes, fantasias, continuo playing, concerto improvisation, thoroughbass fughettes, and finally, improvisation of fugues. By the way, do you want to learn to play the King of Instruments - the pipe organ? If so, download my FREE video guide: "How to Master Any Organ Composition" in which I will show you my EXACT steps, techniques, and methods that I use to practice, learn and master any piece of organ music. When beginners first decide to start playing the organ, they inevitably have a question: where to begin? Having an answer to this question is crucial to the advancement of an organist.

Without a clear understanding of what are the strengths and weaknesses of any particular approach, it will be very difficult to succeed in developing one’s technique. In this article, I will give you my thoughts on this topic. First of all, let me say this: if you have a teacher or a mentor whom you can trust, do as they tell you. It is important that you accept and follow your teacher’s suggestions. Otherwise, he or she can’t take full responsibility for your development. When I first started to play the organ, my teacher asked me to choose a choral prelude from the Orgelbuchlein by J.S.Bach. Imagine that – playing from Orgelbuchlein right from the beginning... I have to admit, although I had a fairly well developed piano technique (I played the piano for 10 years before starting taking organ lessons), I had much trouble with this chorale. I did not know the reason why it was so difficult then, but now I can confidently say it was so because it had 4 independent voice parts (one in the pedal). Talking about Orgelbuchlein, it would have been better to start with the trio texture with 3 independent voices (chorale prelude “Ich ruf zu Dir, Herr Jesu Christ”), because it does not require to play two voices in one hand, which makes too difficult for a beginner to control the articulation. So going back to this topic you can see, that if the organist chooses a piece from the repertoire, it should be a wise choice. On the other hand, having a good organ method book , proceeding from the beginning and diligently following the instructions might save a lot of precious time. You see, the author who writes a particular method book gives you not only very specific exercises to develop your organ technique, but usually a good method book is structured in a very graded manner – from easy to difficult exercises and compositions. A traditional method book might start just with a single line and large note values and proceed a little bit further and involved with each set of exercises. This way the beginner might not feel overwhelmed by the subtleties of texture and technique. I understand that in many cases method books have long sections with dry unmusical exercises which are focused just on one particular element of organ technique, like pedal playing and the organist is supposed to complete them all. Organ pieces sometimes are only at the end of such method. For some people, this approach might be too boring. Isn’t the most beautiful organ music that they first heard was the most important reason for them to start playing this instrument in the first place? And here they are forced to play these exercises for many pages. Perhaps they could feel better about them if they had their goal , vision, or a dream in mind. For example, imagine that the organist wanted to play some piece that he or she always dreamed of, like the D Minor Toccata and Fugue by Bach or Toccata by Widor . But this organist would understand that they are too complicated for a beginner and start studying organ from the method book first with this goal in mind. In fact, it is possible to use a mixed approach. With this approach you would study exercises from the method book but integrate compositions from the repertoire of your level, too. Incidentally, the best method books available today integrate pieces within the exercises or construct the exercises out of the excerpts of the pieces. In addition, such a book also has extensive details on early organ technique, registration, ornamentation, service playing, organ construction, and even on the new late 20th century techniques. Another option would be to start playing the organ with very easy pieces from organ repertoire, such as the chorale prelude “In dulci jubilo” by Johann Michael Bach . However, be aware that you will need to figure out many details by yourself which otherwise would be included in the method book. These details include choice of fingering, pedaling, articulation, registration, ornamentation etc. So you still probably would need to consult your teacher or a method book. Otherwise, your solutions might not be the best and the road to mastering these pieces would be too long. Following the directions from your method book in a way is like studying with an experienced teacher but without the benefits of feedback, motivation, encouragement, and support. By the way, most of the teachers I know use method books in one way or another in their teaching. In the end, I would say that it is possible to start playing the organ with any approach described here. Of course, the choice is yours but my recommendation would be to choose and practice wisely. Treat the pieces like the exercises, find and isolate the difficulties, practice them diligently and you will have no trouble in mastering any organ piece . By the way, do you want to learn to play the King of Instruments - the pipe organ? If so, download my FREE video guide: "How to Master Any Organ Composition" in which I will show you my EXACT steps, techniques, and methods that I use to practice, learn and master any piece of organ music. Dieterich Buxtehude (c. 1637 – 1707) was a representative of North German Organ School and a famous composer of the Baroque period. Buxtehude composed music for various vocal and instrumental genres, and his works and personality had a strong influence on many composers, among them J.S.Bach.

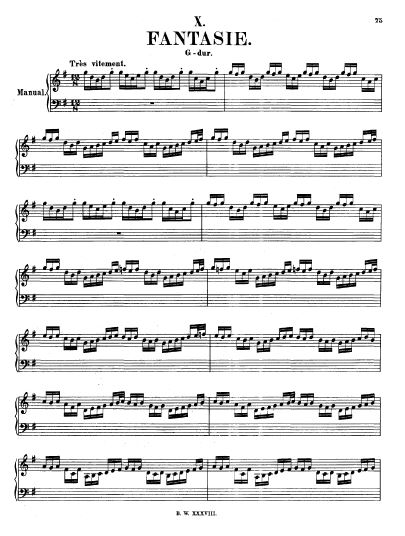

Today Buxtehude with Heinrich Schütz is considered as the most important German composer from the middle-Baroque period. In this article, I will give tips and advice on how to play and practice perhaps the most popular work by Buxtehude - Prelude in C Major, BuxWV 137. The prelude (Praeludium, Praeambulum) is a genre of keybord music with no pre-existing choral melody which was refined by Buxtehude. Praeludium C-dur, BuxWV 137, a perfect example of this type of organ composition in Stylus fantasticus, begins with a imposing virtuoso passagio for pedal solo and imitative episode with dotted rhythms which leads to a fugue. After the fugue folows the ciaccona, e.g. variations of basso ostinato (ground bass) type. This theme is placed in a pedal part upon which the hands play imitative variations. The Praeludium ends with final virtuoso passages. The choice of pedaling for the opening pedal solo is alternate toe technique. Using this technique we avoid heels and play with toes only with right and left feet in alternation. Because this passage consists of solo melody, it is very appropriate to play it quite freely, emphasizing the highest notes of the line. Allow enough time to listen to the echo during the rests and do not rush. On the contrary, a great way to play dramatically is to come in a little late after such rests. The next episode with dotted notes is supposed to be rhythmically strict and precise. One common mistake organists do while performing the opening episode and the fugue is that they lose track of the pulse and play it in different tempos. Since only one meter is given at the beginning (C), everything up until the ciaccone should be played in one tempo. Because this particular fugue is a polyphonic composition which has four highly independant parts, I recommend practicing in shorter fragments in a slow tempo. First, practice each voice separately, then combine two voices, later add three voices, and finally, play all four voices. When you will know shorter fragments, combine them into longer episodes. By the way, I highly recommend to memorize at least this fugue for a true mastery. Use the articulated manner of playing which means that there should be small distances between notes. Avoid using finger substitution, which is more appropriate for the legato technique. However, make sure that the notes would not sound too detached or choppy. The correct articulation could be achieved if you will feel the alternation of strong (1 and 3) and week beats (2 and 4) in a measure. Since Buxtehude was influenced by the Italian tradition, his ornaments usually start from the main note or from the note which is more dissonant. For instance, at the end of the theme of the fugue, you could add a mordent on the dotted G note starting from the main note. The mordent could have three (GAG) or five (GAGAG) notes. Make the first note of the mordent a little longer. Additionally, you could play a mordent in each instance where the dotted note appears at the end of each theme. Note the meter change (3/2) at the beginning of the Ciaccona. Here too, do not lose sense of pulse and play in the same tempo. The tempo relationship could be as follows: one quarter note of the fugue will be equal to one half note of the ciaccona. In the last 5 measures of the piece returns the opening meter and the beginning tempo relationship. If you use such ratio of the tempo, you will achieve a great unity in movement. The most common registration of this type of piece would be Organo Pleno, or Principal chorus with low reeds in the pedals. Feel free to use the Pleno sound on the secondary manual as well for the episode with the dotted notes or the fugue. I use the Breitkopf edition of Buxtehude's organ work s which is solid and quite reliable. By the way, do you want to learn to play the King of Instruments - the pipe organ? If so, download my FREE video guide: "How to Master Any Organ Composition" in which I will show you my EXACT steps, techniques, and methods that I use to practice, learn and master any piece of organ music. Pièce d'Orgue in G, BWV 572, also known as Fantasia in three parts, is written in a French style. It originated rather early in Bach's career (before 1712). The first part is entitled as Tres vitement (very fast), the second - Gravement (heavy) and the final part - Lentement (slow).

Because of fast runs and passages, the opening and closing parts remind of a toccata, and the central solemn episode is written in a 5 part polyphonic texture. In this article I will give tips and advice on how to play and practice this wonderful composition. The Italians would call the opening section the Passagio which was also a common feature in the North German Praeludia. However, it is questionable whether the Italian term is appropriate in the French style composition. Basically it is a virtuosic episode written in a monophonic texture where we can find both the elements of arpeggio and scale-based passages. At any rate, even at this early stage of Bach's career, the composer shows a unique angle of blending multi-cultural elements in one work. Although written in deceptively simple and clear one-voice texture, the opening section has various potential dangers for an organist. This includes note grouping and articulation. Note groupings have something to do with the meter signature which is 12/8. Such a meter has 4 relatively accented beats (on sixteenths 1, 7, 13, and 19, or if we count the eighth notes – 1, 4, 7, and 10). In a measure of such a meter, there are four groups of sixteenth notes. Each group has 6 notes. However many sixteenths are grouped not by the meter requirements, but according to which hand has to play them. For example, in measure 2, the sixteenths are grouped in threes for the right hand and left hand respectively. If we play and make accents according to such a grouping, then inevitably the listener will have the feeling of triplets which is not the correct way to play this passage. Instead, the organist should try to make very gentle accents on every other note and emphasize beats 1, 4, 7, and 10 of the measure. Concerning the articulation, articulate legato touch should be used which was the traditional way of playing any instrument in the Baroque period. Articulate legato means that there should be very small distances between each and every note. However, this does not mean, that the musical passage should be choppy and very detached. On the contrary, the organist should strive to have a Cantabile or singing manner of playing where the notes are connected into one line. However, playing with articulate legato touch in such a lively tempo is not exactly easy. Try to keep all your fingers in contact with the keys at all times. Practice in a slow tempo and with correct articulation. Rhythmically lean on the places where there are important changes of harmony (before measures 17, 21, and 27). Slow down before reaching the end of this section so that you could naturally connect it with the next central section. In the longest main central section, we can hear very imposing stepwise rising theme in long note values which is treated in a fugal manner in various voices. This is a typical French 5 part texture, because the French employed 5 stringed instruments in an ensemble (2 violins, 2 violas, and a violon). Therefore, many of the French classical type of compositions are written in this texture as well (especially the fugues). By the way, can you guess what kind of ominous chord sounds at the end of this section? This central section raises various performance difficulties for many organists. Notice that the meter signature is alla breve or cut-time. That means that there are really two beats per measure and the first is strong and the second is weak. The harmony also changes mostly twice per measure. We have to be aware of that and emphasize rhythmically various important harmonic changes, especially occurring in cadences. Apparently for Bach this central section was like a case study in suspensions. Just look at any measure you want and you will see tied notes over the bar lines. The suspension technique gives a constant feeling of tension and continuity. Most of the cadences in this section are deceptive. That means whenever Bach ends a fragment in one key, he does not use chords of the Dominant and Tonic but rather Dominant and the chord of 6th scale degree. Try to emphasize rhythmically these cadences. Such an approach will help you to clarify formal structure of this section. Because this section is written in 5 independent voices, there is an inherent danger that the organist will not be able to listen to each separate line, everything will just sound legato, and correct articulation will be lost. In other words, it is easy to understand that all the notes should be played with articulate legato touch but the suspensions over the bar line make it exceedingly difficult to control the releases. If you truly want to have a precise articulation, my suggestion would be to take a fragment of four measures and practice each of the 5 voices separately, then combinations of 2 voices, 3 voices, 4 voices, and only then practice playing the entire 5 part texture. Then take another fragment of 4 measures etc. Practicing this way will ensure that your articulation will be unbeatable and that you will hear each part separately which you have to strive for in every polyphonic composition. Pièce d'Orgue ends with a virtuosic but a little slower and heavier texture which has 5 voices encoded: 4 voices could be perceived in both hands and magnificent Dominant pedal point in the pedal line. Try not to play this final section too fast because it has a tempo marking Lentement. Like in the opening section, here too, the notes are grouped according to which hand plays which of the three note groups. When you play them, instead of emphasizing two groups of triplets, try to feel three groups in each sextuplet. Make a natural connection between the hand part and the magnificent long Dominant pedal point in the middle of the measure 200. Because this is the French style piece, the ornaments also should be performed in such a tradition. Always start the trills and mordents from the upper note. By the way, it is worthwhile looking at the heavily ornamented version of the middle section in the Neue Bach Ausgabe edition (Volume 7 of Bach Organ Works ). You can try to adapt many of the ornaments in your performance, too. The most trusted registration of this piece obviously would be Principal chorus or Organo Pleno (with or without 16’ in the manuals). Manuals could be coupled as well. The use of the deep pedal reeds, such as Posaune 16’ (or 32’ if there is one on your instrument) is most welcome. If you use a modern instrument with unnaturally sharp sound mixtures, sometimes it is a good idea to add some additional 8’ and 4’ flutes in the manuals for thickness. Feel free to play on the secondary manual in the opening section, if you wish. In this case, avoid using 16' in your opening registration. That way you will achieve the true gravity which Bach wished for his Pleno sound. I have created BWV 572 Video Training which will help you master Bach's Piece d'Orgue. Overall, this is a rather difficult composition to play. If you are new to the organ, I suggest you start with shorter free works, such as 8 Short Preludes and Fugues for organ earlier attributed to J.S.Bach and leave the Piece d’Orgue for the future. At any rate, even an experienced performer should have much perseverance and attention to detail while practicing this wonderful work. Memorizing the piece would give the organist a full mastery at a much deeper level. Many organists want to be able to play the most wonderful organ compositions from memory. This skill lets them to know the music at a much deeper level and gives many advantages against the organists who do not work on memorizing their music.

But is it possible to store the music in our permanent memory so that we could play it after many months? The answer is yes, and this article will show you how to do it. First of all, we have to understand that after we memorize the piece the next day we have to repeat it otherwise we will soon forget it. What does it take to truly memorize the composition ? We can take the analogy with learning the words of the new language. Just imagine if you have to memorize 5 new words in a foreign language today. How many times you have to repeat them in order to memorize them? Perhaps repetition of 10 times each would be enough for most people. Will you remember them tomorrow? Not really, unless you repeat them tomorrow, right? So, if you repeat them tomorrow, will you remember them permanently? Not yet. We have to repeat them about 100 times over a long period of time to be able to remember them permanently. In other words, repetition of just 10 times stores them in our short-term memory, but if we repeat them 100 times over some months, then we will have them stored in our long-term memory. Going back to organ playing, we can also use a similar system how you could go about in memorizing music and keeping it in your long-term memory. We will use a special 11 step strategy. 1) Memorize the music. Repeat it 10 times. 2) Repeat it after 1 day 10 times. 3) Repeat it after 2 days 10 times. 4) Repeat it after 4 days 10 times. 5) Repeat it after 1 week 10 times. 6) Repeat it after 2 weeks 10 times. 7) Repeat it after 1 month 10 times. 8) Repeat it after 2 months 10 times. 9) Repeat it after 4 months 10 times. 10) Repeat it after 6 months 10 times. 11) Repeat it after 1 year 10 times. Note that the length of the piece does not mater as long as you repeat so many times. However, I suggest you try something shorter for starters. After 1 year you will have 110 repetitions of this piece and it will be stored in your long-term memory. Then you can leave it for many months, but your will not forget it. However, I don’t mean you should be playing ONLY this piece for one year. Of course, play and other organ compositions but this is for the sake of an experiment. You can memorize more pieces, if you will have time. Now try this for yourself and I would like to know how it will work for you. It certainly did work for me. By the way, do you want to learn to play the King of Instruments - the pipe organ? If so, download my FREE video guide: "How to Master Any Organ Composition" in which I will show you my EXACT steps, techniques, and methods that I use to practice, learn and master any piece of organ music. Not every organist who plays this instrument masters the organ playing and achieves the high level. Many fail to stick with it for a long time and quit before they even start to see the results of their playing. This can happen because they fall into one or more pitfalls that slow down their progress. Avoiding these mistakes can save you much precious time and energy.

1. Having too many wishes. Because so much of the organ music is so beautiful, sometimes people cannot decide which pieces are the most important to them to practice for the moment. They watch videos or listen to recordings, find a piece that they like and start practicing. However, the next day they might find another piece and the same will happen. And so they have just too many pieces to learn for one practice session. Only the very best organists with much experience and extraordinary sight-reading skills can prepare for several recitals simultaneously. So limit your wishes and keep other pieces waiting for you in the future. 2. Laziness. Let’s face it, many people are just too lazy to learn to play the organ. Although this can be changed, they spent most of the time wishing they could be practicing and dreaming of how to become skilled in organ playing instead of just sitting down on the organ bench and start practicing. If you are serious about organ playing, never let a day pass without some practicing. Even if the full practice time is unavailable to you, you can spend some 20 minutes just repeating what has been learned the day before. Remember, there is a saying, if you miss one day of practice, only you will notice it. If you miss two days, your teacher and your friends will notice it. If you spend three days without practice, everyone will notice it. 3. Lack of prioritizing. The reason many organists do not practice regularly is due to their poor ability to prioritize. If they have other responsibilities besides playing the organ, they need to set firm priorities what is most important to accomplish each and every day. Do the tasks which are urgent first, then the important tasks, and only then the tasks that can wait. If you don’t have or don’t follow your priorities during the daily tasks and do only the things that you love first, then the urgent tasks still need to be done. Spending the day this way can mean that you will not have enough time to practice organ. 4. Practicing without a goal in mind. How many times do we sit on the organ bench and just go through the motions. We may play the piece once or repeat it several times but without being aware what we need to accomplish here. Ask yourself these questions regularly. Was the posture, hand, and foot position correct? Did I play the notes in this episode correctly? Were the fingering and pedaling without mistakes? Did I play the rhythm correctly? Was the articulation precise? If the answer to any of these questions was “No”, then go back and do it correctly a few times. If you are aware of these goals constantly while practicing, your performance level will improve dramatically over time. 5. Not having an experienced mentor. Having a mentor, a teacher or a coach is crucial to your advancement. Although there are manuals, textbooks, and tutorials from which you can learn many things about organ playing, having a person whom you can trust is even more important. There is one specific issue that needs to be addressed here: a good mentor will hold you accountable for your actions. He or she will not listen to any excuses. The mentor will push a little further each time you say “I can’t”. This is because the mentor was in your shoes once, mastered something, and can share this skill with others. 6. Not listening to the mentor you trust. What happens if you have a good mentor but you don’t follow his or hers advice? Of course, your progress will be much slower. What happens if your mentor tells you to practice for two hours a day, and you only practice for 30 minutes every other day? What if your mentor asks you to memorize a page of music, and you only memorize one line? Mentors are supposed to be strict. Only then real progress can be seen. But remember, only you are responsible whether or not you accomplish the task that your mentor asked to do. So trust your mentor and try not to make excuses. 7. Habit of not finishing tasks. Some people choose a piece of music, play it, practice it but never really master it. Long before they know the piece, they take another one. This approach will not get them very far. This can happen if the piece has places that organists cannot master easily. So they switch to another piece. I say this way people can eventually quit practicing the organ altogether. We have to finish what we start unless the piece is really too difficult for us for the moment. If this is the case, ask your mentor for advice. Realizing these common mistakes that organists often do and consciously avoiding them will help you to become a better organist. Be serious about your progress and you will reap great results. By the way, do you want to learn to play the King of Instruments - the pipe organ? If so, download my FREE video guide: "How to Master Any Organ Composition" in which I will show you my EXACT steps, techniques, and methods that I use to practice, learn and master any piece of organ music. The Prelude and Fugue in C major, BWV 553 is included in the collection of 8 Short Preludes and Fugues formely attributed to J.S.Bach. Although the author of this piece remains unknown it is generally reffered as a composition of the Bach circle, possibly by Johann Ludwig Krebs.

This popular work can be played on the organ in these 8 easy steps. 1. Analyze the form and tonal plan of the piece. Play this composition a couple of times so that you could understand the structure of the prelude and fugue. The prelude is in a binary form, which means that it consists of two parts, each of them repeated. The first part ends with the cadence in the key of G major, which is the Dominant of C major. The second part also has a cadence in A minor, and ends in C major. When analyzing the fugue, count the appearances of the subject or the theme. Note the keys that the theme is in. 2. Write in fingering and pedaling. Playing with correct fingering and pedaling has many advantages, it gives you much precision and clarity. Therefore, when you discover some trouble spots in the music, it is best to write in the correct fingering so that you will never have to think about it again. I recommend writing in the pedaling on every note. Use alternate toe technique and avoid using heels. 3. Make sure the articulation is precise. Once you have fingering and pedaling in place, you have to decide on the correct manner of articulation. In the Baroque period, the normal way of articulating notes was so-called ordinary touch or articulate legato. This means that the notes in the piece must be somewhat detached. However, they should be played in a singing or cantabile manner. 4. Decide on ornamentation. The trills in this piece should be played from the upper note. Although there are only one trill noted in the prelude and three in the fugue, you should feel free to add similar ornaments in every structurally inportant place of the piece. In other words, the trills can be played in every cadence. 5. Decide on tempo. The normal tempo in this piece should be somewhere around 80 in the metronome. However, for practicing purpose use much slower tempo. Always try to feel the strong and week beats of the measure. 6. Decide on registration. The registration for this prelude and fugue should be Organo pleno, or principal chorus with or without 16‘ in the manuals. On some modern organs with very screamy mixtures, this registration works best if you add 8‘ and 4‘ flutes. 7. Practice the piece. When practicing this prelude and fugue, you can work in fragments of 4 measures or even shorter. When these fragments become easy, combine the fragments and practice longer episodes. However, whenever you make any mistake, go back a measure or two, correct it and play this fragment a few times. 8. Memorize the piece (optional). Although memorization is not required, you will play with greater confidence if you know the piece from memory. These are the steps necessary to play and learn this composition. If you follow them precisely, you will be rewarded by the wonderful impact the music can have on the organist. If you intend to practice this piece, check out my practice score of the Prelude and Fugue in C Major, BWV 553. It has complete fingering and pedaling so you could start practice immediately. By the way, do you want to learn to play the King of Instruments - the pipe organ? If so, download my FREE video guide: "How to Master Any Organ Composition" in which I will show you my EXACT steps, techniques, and methods that I use to practice, learn and master any piece of organ music. Reading music can be a challenging task. Some people believe that this skill cannot be taught. This is not correct. Just like any other skill music reading can be taught, practiced, learned, and perfected.

In this article, I will discuss some of my personal favorite techniques which might help you to get better at music reading. Use them regularly and over time it will get easier for you to sight-read musical scores and organ compositions. There is one thing which I have to clarify here. These suggestions are for people who already know how to read notes of the treble and bass clef. If you are looking for tips how to learn to read music from scratch, this article will not teach how to do that. Instead, it will give you the advice on how to get better at sight reading. First of all, let us think about the chorales and chorale harmonizations by Bach. They are so beautiful and their harmonies are spectacular. We know that Bach never wrote a treatise on harmony. But these harmonisations are like a real textbook of harmony. Many theorists after Bach analyzed them and developed a system of tonal harmony. So going back to these chorales, one thing I do regularly is to sight-read them. Just one page per day. Of course, many people have difficulties in playing Bach's chorale harmonisations. You see, although these pieces are short, they contain 4 fairly independent parts. So it might be too hard to play such a choral for you. If this is the case, this is what I would do: Take one page per day. But don't play both hands and feet together yet. Start with one voice only: the soprano and play one page just this voice quite slowly. Take a comfortable tempo. The next day play next page the soprano again and so on until you reach the end of the collection. You will start noticing much improvement along the way. By the time you finish the collection, the soprano line will be easy for you. Then start sight-reading other voices like you did with the soprano (bass in the pedals with the 16' registration). Then play in combination of two voices... Then in 3 voice combinations... Finally, play all parts together (soprano and alto in the right hand, tenor in the left, and the bass in the pedals). This approach takes a while to go through various voice combinations. But in the end you will feel much more confident about reading music. If you really want to develop unbeatable sight-reading skills, check out my systematic Organ Sight-Reading Master Course which is intended for organists who want to perfect such seemingly supernatural abilities as playing fugues or any other advanced organ composition at sight. To successfully complete the practice material of this course will only take 15 minutes a day of regular and wise practice but you will learn to fluently sight-read any piece of organ music effortlessly. |

DON'T MISS A THING! FREE UPDATES BY EMAIL.Thank you!You have successfully joined our subscriber list.  Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas

Authors

Drs. Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene Organists of Vilnius University , creators of Secrets of Organ Playing. Our Hauptwerk Setup:

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

This site participates in the Amazon, Thomann and other affiliate programs, the proceeds of which keep it free for anyone to read.

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed