|

Today I went to the church and practiced this beautiful Adagio by Alessandro Marcello. The more I played, the more ornaments I added. Hope you will enjoy it!

Score: https://www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/adagios-for-organ-sheet-music/16572019?aff_id=454957

Comments

Total Organist and Secrets of Organ Playing Midsummer 50% Discount (until July 1).

Vidas: Hello and welcome to Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast! Ausra: This is a show dedicated to helping you become a better organist. V: We’re your hosts Vidas Pinkevicius... A: ...and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene. V: We have over 25 years of experience of playing the organ A: ...and we’ve been teaching thousands of organists online from 89 countries since 2011. V: So now let’s jump in and get started with the podcast for today. A: We hope you’ll enjoy it! V: Let’s start episode 598 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Vivien, and she writes: “Thank you so much for your acknowledgment and interest Vidas. Next time I will understand better how to enter the amount of money and make it more in line with the quantity and quality of expert help coming from you and Ausra. Lockdown means no Church Services and so has given me a chance to improve my basic skills instead of being stressed with deadlines. I’m trying to improve my trills and am using a manual piece Jesus, meine Zuversicht, BWV 728. I listen to Wolfgang Stockmeier because I happen to have his CDs, copy him and then record myself. The long trills still sound awkward, but then I found your advice of slow, exact and emphasising every other note which I’ve never read before. Feeling optimistic that this could be a breakthrough. Can’t believe the way that you understand such detailed problems. I hope that you both are coping well in this crisis. Best Regards Vivien” V: So, Ausra, what comes to mind when you read this message? A: I remember my way of dealing with trills, actually. V: And? Was it a long time ago? A: Yes, it was a long time ago, but actually I struggled with playing trills well for quite a long time, and I think what I had was not so much as a physical incapacity to play them right, but something in my head that I was so much afraid of trills that when the trill would come, I would get like a muscle spasm or something and couldn’t execute them right. V: In long trills, you mean? Or short ones? A: Yes, usually in longer. The longer the trill, the bigger the problem was. V: For me, the pedal trills are quite complex, or actually I should say was quite complex. Remember the B-A-C-H by Liszt, “Prelude and Fugue on B-A-C-H,” and there is this pedal trill toward the end, a long one, and expanding to the next measure and the next measure… A: Yes, I remember this piece, it’s fun! V: ...in the last measure, in the last page, I think… I was struggling with it for a long time. A: That’s funny because, you know, this was one of the easiest pieces that I have played that sounds really hard. I don’t know.. I learned it very fast, and it gave me none of the technical difficulties. V: Even in the pedals? A: Yes, even in the pedals, because you don’t have to play like double trills to play a trill with one foot, you just use both of your feet, and that’s it! V: I don’t remember if it’s a double trill in octaves or not. A: No. V: No. You know what? I always admired your ability to play long trills with 3-4-3-4-3-4 fingers. A: Yes, but I only can do it on a tracker action, because on our Hauptwerk, on the plastic keyboard I cannot do it. I use the 2-3, 3-2. V: What’s your secret then, in playing trills? A: Actually, what helped me to overcome those spasms was breathing. Basically, I just have to breathe. Don’t forget to breathe before the trill and during the trill, especially if it’s a long one, and somehow it relaxes my muscles and I can play it successfully. Of course, another thing is that, well, you need to preserve the rhythmical structure of the piece, because what happens often with the beginners is that when the trill comes, that they simply lose the sense of the rhythmical flow. So what I would do if I were a beginner is that I would learn a piece or at least play it a part of the way through without trills, just omitting them for a while. And then, when I would be really comfortable with the text, then I would add them. That would preserve the rhythmical structure and of course, another thing is, as you said to Vivien earlier, how you accent the trill in order to make it correct, but then another way would be to not play it so strictly rhythmically, because if you will play it in a final version and emphasize each other note, it will sound ridiculously unmusical. V: Yeah, it would sound artificial. A: Yes, so basically what I do with my long trills is that I start slowly, and I speed up, and then towards the end I slow down again. And then, it becomes more natural. V: Good violinists play like that in Baroque music, so it’s good to listen to violin trills and then copy them. Why didn’t you tell me about breathing when I was struggling with the B-A-C-H by Liszt trills? A: Well, it was such a long time ago that I don’t think I had developed my own technique at that time. V: Yeah. I wish I had known this advice earlier. A: It helps for hand trills. I don’t know if that would work for the pedal. V: Probably still! Everything tenses up when you stop breathing. Your ankles, too. Yeah, probably would help. So guys, keep breathing when you’re playing trills, and practice, of course, slowly at first. Vivien doesn’t make a mistake here with practicing slowly at first, when you’re just first getting the hang of the trill, but when it’s more naturally to you, then you can apply Ausra’s advice, too. A: Plus try different fingerings sometimes. I would not suggest you to try the fifth and the fourth finger because it probably wouldn’t work, maybe for you it would, but try the fourth and three; for some people it works, like for me on the tracker organ. If that doesn’t work, then try 3-2. Actually, try 3-1! This works sometimes quite nicely, because it’s sort of a natural hand position. And even for some people 1-2 might work, so it’s according to each of our individual natures. So try all these combinations and see what works best for you. V: I even in some piano exercise, I think it was… it might have been Hanon drills doing it like this: 1-3-2-3-1-3-2-3-1-3-2-3, like this. A: Yes, it makes sense sometimes! V: It’s a romantic technique, not necessarily Baroque. But if you’re playing later music, why not? Of course later music doesn’t have as many trills! A: That’s right! And another suggestion, if absolutely some of the trills don’t work for you and you can’t play them gracefully, then just omit them in your final performance, because really, the trill that is not executed nicely can ruin an entire piece. V: I agree. A: So it’s better to do less ornamentation than to do it in a not graceful manner. V: While we are talking about this, would you recommend people starting include ornamentation right at the beginning of the learning process, or somewhere in the middle? A: Well, it depends on how much you struggle with it, because for people for whom trills ruin the rhythmical structure of the piece, I would suggest to learn to play, to practice the piece from the beginning without any ornaments. If it’s not an issue, then you can add ornaments right away. V: Yeah, in music schools, teachers usually omit the trills for a quite some time so students don’t get used to them, and then they struggle while adding them just in the final month or so. A: That’s in general. Pianists, most of the time they don’t know how to play the ornaments, because they don’t deal so much with the Baroque music, so they are not as good at reading trills as the organists are. V: Yeah, and a good table of ornaments if you’re playing music of J. S. Bach is the beginning of his “Klavierbüchlein für Wilhelm Friedmann Bach.” He copied, I think, the Frenchman’s d’Anglebert's table of ornaments there. So that’s why we use the French style of ornamentation. A: But again, you know, if you are playing other composers, such as Buxtehude, for example, then you have to follow with the Italian way of ornamenting. V: Yes, starting from the main note, not from the upper note. But there are exceptions, of course. So many things to talk about. Maybe we will leave it for future conversations. Thank you guys, this was Vidas, A: And Ausra! V: Please send us more of your questions; we love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice, A: Miracles happen. V: This podcast is supported by Total Organist - the most comprehensive organ training program online. A: It has hundreds of courses, coaching and practice materials for every area of organ playing, thousands of instructional videos and PDF's. You will NOT find more value anywhere else online... V: Total Organist helps you to master any piece, perfect your technique, develop your sight-reading skills, and improvise or compose your own music and much much more… A: Sign up and begin your training today at organduo.lt and click on Total Organist. And of course, you will get the 1st month free too. You can cancel anytime. V: If you like our organ music, you can also support us on Patreon and get free CD’s. A: Find out more at patreon.com/secretsoforganplaying Total Organist and Secrets of Organ Playing Midsummer 50% Discount (until July 1).

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 308 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Jaco, and he writes: Dear Vidas Thank you for your daily posts - it is really an inspiration! I really like Bach's Toccata in d (Dorian). It is a piece that feels like it has perpetual motion - something always keeps moving in it. It is quite a difficult piece to master, but I decided to learn it. The edition I am playing from is the new 2012 urtext Breitkopf & Hartel edition. It indicates a trill in measure 29 on the top e in the RH (please see below). However, it does not indicate when this trill should stop. The note is held on for another 2 measures. When should that trill stop? I don't know how to play the RH in measure 30 if trill has to continue, since a lower voice starts with that hand halfway through measure 30. Another question - I know the piece has to be played articulate legato. However, it does sound quite nice if the first 2 semiquavers on the motive on beat 1 and 3 are slurred (played legato). I have heard it on some recordings as well. Would this be considered acceptable to do? Looking forward to your reply! Kind regards Jaco V: So, in measure 30, on the second half of that measure right hand, 16th notes enter. And, if you were to continue this trill, it would be impossible to play double-16th notes in the left hand in parallel 6ths, Ausra. What do you think? A: Well, unless you would use the 5th and 4th finger to make the trill. V: Oh, that’s...that’s torture! A: It is! Or maybe you could play those 16th notes with your left hand. V: But you see, can many people play double-parallel-6ths in that tempo? In the really fast tempo? A: I don’t think so. But it would be so nice, you know, to have that trill until the measure 31 where you have those chords in a cadence. V: At least in the middle of 30, when the right hand enters with 16ths, too. But, you say you would try to play it with the left hand, right? Both voices that move in 16th notes. A: That’s one of the possibilities. V: Technically, it could be done, A: Yes, it could be done… V: Because the distance between those two parts is not more than one octave. So, technically, if you are good with your left hand, it could be done, but, in reality, not too many people can do this. Yes? So then, you sacrifice something. A: Well, yes, but in general, while using the sense of your mind, I think you would stop playing that trill when the second voice in the right hand enters. V: That’s what I’m thinking, too. A: In the middle of the measure 30. V: That’s right. A: Is it measure 30? Yes. V: Okay, so that’s our solution, and I think Jaco feels that way, too, because it’s impossible, really, to play perfectly the long trill and both voices in the left hand, unless you are a virtuoso. A: I think that’s what Bach meant, to play the trill until the 16ths enter in the right hand. V: What about playing a short trill, just like four or five notes? A: I don’t think it will work in this piece. Could you go back to the score, please? ...because, as Jaco already said, it’s perpetual motion in this piece, and this starts right away with both hands, and pedal comes in here, and then you have the trill in the right hand, and if you want to play it or you do it very short, then I don’t think it will do good for that sense of motoric movement. V: I just have to double-check the older edition from the 19th century, from 1861, Bach-Gesellschaft-Ausgabe. What does it say? If it’s a long trill or a short trill….it might be something different. And sometimes 19th century solutions are better than 21st century solutions. A: Well, it’s good to know more ways than one, you know? And to check more editions. V: Okay. Let’s see...we’re looking now, and trying to find… this trill is in parentheses in Bach-Gesellschaft-Ausgabe on which our version with fingering and pedaling is based! So you could play it, or you could not play it, I guess. A: I would play it, because if you would just hold that long note… V: True.. So then, Jaco has another question. He writes: “I know the piece has to be played articulate legato. However, it does sound quite nice if the first two semiquavers on the motive on beat one and three are slurred—played legato. I have heard it on some recordings as well. Would this be considered acceptable to do?” That’s a very fast tempo, and… A: It is! V: in such a fast tempo, A: It might sound legato. V: Right. A: Actually, I don’t believe that somebody on purpose played those two semiquavers legato. I think it’s just a feeling you get when it’s played in a fast tempo. And because you have to emphasize the strong beat, that’s why it sounds legato, too. V: Because you make the first note longer. A: Longer. That’s right. But, somehow to try on purpose to play it legato, I wouldn’t do it. V: Plus maybe the acoustics environment will make it sound legato. A: True. V: But the organist probably would still play with articulation. It’s different from what the organist does and what the listeners hear A: That’s right. V: Interesting piece! A: Because, if you play legato on purpose, then you might get a mess, or your listeners might hear a mess. V: I played this piece many years ago, when I was still a student, and I struggled with playing it in an even manner, because it’s a motoric piece, like a toccata, and after a while, after a few pages, it gets quite difficult, just like in Vivaldi-Bach Concerto, D minor, the last movement. A: And it’s like C minor Prelude from Well Tempered Clavier, the first volume also very motoric. V: Yes. Organists have to develop good patience while working on this piece, otherwise, we can lose a sense of meter! A: True, and I think it would be a crucial point in a toccata if you would lose your sense of motion—that sense of meter. Your toccata would be lost to it. V: I wonder how Jaco is practicing the fugue. He doesn’t say anything. Because, the fugue is, I think, more complex! A: True! V: With so much canonic motion. A: Yes, because the toccata, there, is not much of polyphonic devices, but fugue is another thing… V: And, sometimes the fingering is tricky. That’s why we made fingering and pedaling for both toccata and fugue, of D Dorian, and hopefully people can practice efficiently using our score, too. Okay guys, thank you, Jaco, for this wonderful question, and others, please keep sending us your feedback and your stories. We love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice, A: Miracles happen! Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start Episode 190 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. This question was sent by Neil. He writes: Hello Vidas, I’m trying to learn this fabulous piece but finding the ornamentation a challenge. Can you advise on correct fingering and ornamentation? I enclose the link to the collection of Purcell pieces via IMSLP website and the voluntary is on page 64. http://imslp.org/wiki/Harpsichord_Music_and_Organ_Music_(Purcell%2C_Henry) V: And he encloses the link to the collection of Henry Purcell pieces on Petrucci Music Library website and he playing the voluntary that is on page 64. So were looking at the page 64 right now and it appears it has a lot of various ornaments, graces as they are called. So what should Neil do for starters? A: Well you know if I had been in a situation like he is and would have a piece where I could not understand some of the ornamentation I would look at the beginning of that collection because it gives all of the rules for graces. V: Not only for graces right? They also explain its a big preface right? With notes, with dedication to the royal highness the princess of Denmark, right? That Purcell did and also the scale or the gamut, right? The pictures from original score, examples of time or lengths of notes, again you mentioned rules for graces and then fingerings, right? He writes fingering too. So there is also a lot to be learned from preface like this and from introduction. A: I know it’s amazing you know how how how many details Purcell gives for his performance. V: Exactly. We could discuss a little bit the types of graces, right? A: Yes. V: The first grace is marked with two lines above the note, note stem, right? Horizontally or a little bit diagonally. It’s called a “shake” and if the note is written on the note B like in example then it should be performed C-B-C-B-C-B-C-B in thirty-seconds. A: So from the upper note so it’s like trill. V: Yes, upper note trill. Like french trill, like Bach trill too. A: Sure. V: And then another type of grace is marked like a normal mordent, like a curly line, right? And actually it has to be played from the note below. If it’s on the note B then it has to be played A-B-A-B. A: And that’s different from Bach’s, from french you know ornamentation but probably similar to italian. V: French has this type of ornamentation but A: But we mark differently. V: Then there is a shake with two diagonal lines above the note stem but also like a slash, backslash sign from the computer that we have. And it’s like played with repeated C and then C-B-C-B again. This first C is long like eighth note long and the rest of them are thirty-seconds. A: Yes. V: Um-hmm. Then there is a shake probably but with one diagonal line above B. So that is played from below A-B. A is sixteenth note and B is dotted eighth note. A: So this is some sort of appoggiatura version. V: Exactly. But english have their own version of everything. A: Yes. V: Um-hmm. Backfall they call it. And the previous one was a forefall. And now B note with an opposite appoggiatura, right? Opposite diagonal line like a falling so you have to play it like C-B. Not A-B but from above. A: Yes. So all those you know tiny differences that are very important for performing such music. V: Hey look. There is another one like a turn. Turn and it is played from the main note. Not upper note. If it’s written on the note B so you have to play it A: From B. V: B-C-B-A-B in thirty-second notes. Um-hmm. Right? And then there is mark like a shake with two diagonal lines but also like a parenthesis, like a slur actually, like a slur from above the note. And they have to be played C-B-C-B-A#-B in thirty-second notes. It’s strange, right Ausra? A: Very strange. V: What else? O you have sometimes two interval. B and D so then it’s like passing notes B-C-D. French they have Tierce culée exact sign too. If you have a chord and a slur before those notes it means you have to play arpeggio. Right? A: Yes. V: But it’s not a very simple arpeggio. It’s very intricate. What do you understand here Ausra? A: Huh. I just. What I understand from this marking is that you have to hold the lower note all the time while arpeggiating the upper note. V: Um-hmm. So then you would need to start with the lower note then skip one note and then play the third note, fourth note and lastly the second note of the chord in order to play this arpeggio. Um-hmm. And then they indicate how various clefs are notated. Bass clef. A: Tenor clef. V: Treble clef and of course they have how many lines, 1-2-3, six lines in the staff. Good luck Neil. I think you will love it. Then of course we could discuss a little bit about the fingering. Because Neil was asking about the fingering too. You see at the end of this example Purcell writes a scale up and down, both hands. So what do you see here? A: Well that he uses position fingering and lots of good fingering too. V: And the strong finger is three in the right hand obviously. So you play 3-4-3-4-3-4-3-4 in ascending line with the right hand and 3-2-3-2-3-2 in descending. And in the left hand what do you do? A: It’s interesting because he uses also a strong finger in the left hand, the three as well. Can you see that? V: Left hand. A: Yes. V: It doesn’t make sense for me the left hand. A: I know it looks sort of V: weird. I’m talking ascending 1-2-3-4-3-4-3-4-3-4. A: I know it’s like all written backwards, I don’t know. V: It’s like the right hand actually. A: I know. V: It’s all mixed up. Maybe he meant downwards this fingering. Wouldn’t you love to see Purcell’s hand? A: (laughs) V: How many fingers did he have? A: Maybe he played like this you know. V: Yes, backwards. A: I know. V: I think you could play 3-2-3-2-3-2 with the left hand ascending and then descending 2-3-2-3-2-3. That would be easier right? A: Yes. V: So, guys always consult the preface if there is one. A: I know but this preface and that fingering of the left hand you can you know damage your left hand. V: And then always consult your mind. A: That’s true. V: That sometimes has a better explanation. A: You have to sort things out always for yourself. V: Um-hmm. Excellent. That’s a fun collection actually. A lot of beautiful suites, variations, and voluntaries that Purcell wrote. A: Yes, it might be very handy for church musician when you need you know short episodes for your service. V: And some of them are hymn related, right? A: True, yes. V: We found one Old 100th hymn. But obviously they are more virginal type of music like harpsichord. A: That’s true but let’s say if you have for example service in a chapel as we for example had at Grace Lutheran Church on Saturday. V: Without the pedals. A: Yes, without the pedals it’s a perfect collection. V: Exactly. Doesn’t hurt to play it. The more variety the better actually. Wonderful. Thank you guys, this was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: Please send us more of your questions. We love helping you grow. And remember when you practice… A: Miracles happen.

Vidas: Let’s start Episode 108 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. This question was sent by Andrew, and he writes:

“Dear Vidas, thank you for your email particularly since you must be very busy judging by all your posts! In reply to your question, I’m currently working on Franck's Final, and hoping to move on to Stanford’s “Rheims” from the second organ sonata, hopefully in time for Armistice Day 2018.. I visited Rheims last year. What do I struggle with? Early fingering and ornamentation, particularly making Early English music sound coherent and fluid. Andrew” So, early English music--that’s probably John Bull, Orlando Gibbons. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: Redford, Tallis... Ausra: William Byrd... Vidas: Byrd, yes. These things. Basically… Fitzwilliam collection. The collection is enormous--it has 2 gigantic volumes-- Ausra: Wonderful collection, yes. Vidas: And I don’t even know how many hundreds of pieces there are from the time of before Purcell, I think--16th century, end of 16th century, late Renaissance; right, Ausra? Ausra: Yes. And I think this collection also includes music by Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck. Vidas: Yes. Ausra: The only one, I think, non-English composer. Vidas: Exactly. So, all those wonderful English composers have a lot of passage work and runs with each hand sometimes, and many many ornamentation instances. Ausra: Yes, you have to be a virtuoso to be able to play these pieces. But there is also a good side about this music: it almost doesn’t have pedal. So you can play it not only on the organ, but also on the harpsichord, and also on the clavichord or virginal. Vidas: Exactly. A virginal is a smaller version of the harpsichord, like a spinet, sort of. Ausra: Yes, it’s really small. Tiny. Vidas: And it works well on the organ, too, I would say. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: I played, a few years ago, in our long recital based on this collection which was devoted to English composers, and I sort of liked it, because then of course, I had to figure out my registration, because it’s not written in the score (because it’s really not for the organ); but I had some imagination with this, and our church organ at Vilnius University St. John’s Church was quite colorful. Ausra: Yes, and what actually helped me to be able to play early music better was the clavichord. Actually, basically the clavichord was the instrument that showed me, really, how to play early music well. Vidas: What’s so unique about the clavichord, Ausra? Ausra: Well, it’s sort of an instrument that teaches you. Teaches you to use correct fingering, then to use the right touch on the keyboard. And if you would be able to play a piece of music on the clavichord well, it will sound good on the organ, too. Vidas: Historical clavichords have shorter keys and very narrow keys; and the touch is so light. And it seems like it’s very easy to play; but it’s not, because you have to use all the big muscles of your back, basically, to give some weight on the keys. Ausra: Yes, yes. And because it’s different from the organ and harpsichord. Because on the organ or harpsichord you can make the sound louder or softer only by adding or omitting stops; but while playing clavichord, you can do actual dynamics just by touch. Vidas: Yeah. And remember, you can do vibrato. Ausra: Bebung, so-called Bebung. Vidas: In German, Bebung, yeah--by gently pressing the key up and down, giving this constant pressure--up and down, up and down. And that’s what the vibration comes from. Ausra: Yes, and then playing on the clavichord, you understand what the meaning of the early fingering is. Because it’s impossible to play early music well on the clavichord while using modern fingering. Vidas: Exactly. So it’s very well suited for English music from the late Renaissance and early Baroque, especially because as we said, the key are very narrow, and the touch is very light, but you have to avoid thumb glissandos. Ausra: Yes, use position fingering. And by position fingering I mean you cannot use the thumb under… Vidas: Under--crossing the thumb under, you mean. Ausra: Yes, crossing the thumb under. Vidas: When you play a scale, for example, from C to C, then in modern fingering we do 1-2-3, 1-2-3-4. Ausra: And then 5-1-5. Vidas: So on the note F, we press with 1. And this thumb… Ausra: Goes under. Vidas: Under your palm. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: And crosses. Ausra: So you cannot do that while playing early music? Vidas: You have to keep positions. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: And shifting the entire palm into the new position. Ausra: That’s right. And also use a lot of the paired fingering. So if you have a passage with your RH, then the good fingers would be 3-4, 3-4, 3-4. Vidas: Yes. Ausra: If you are playing with your LH, the good fingering would be 2-3, 2-3, 2-3. Vidas: And it depends on the region and the country. Sometimes 1-2, 1-2, with Sweelinck, for example. But I wouldn’t worry too much about the differences between the countries--it’s too advanced detail. In general, use paired fingering for passages that remind you of scales. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: And keep position fingering for everything else. Ausra: And if you don’t have access to a clavichord, then practice on the harpsichord, or practice on a mechanical organ. Because if you only practice on an electrical organ or pneumatical organ, it will not do good for such music as early English music. Vidas: Well yes, it will sound unnatural for these modern instruments. And quite boring. Ausra: Yes, it will sound boring on the pneumatical or electric instrument. Vidas: Exactly. So then, another point is about ornamentation. Which fingers do you make ornaments with? Ausra: Well, if I’m playing a trill with my RH, I could do either 2-3 or 3-4. It doesn’t make much difference for me. Vidas: Mhm. Ausra: And actually, with my LH, I could do a trill with 3-2 or 3-1 sometimes even, maybe not so often 3-4 with the LH. Vidas: Mhm, mhm. Ausra: But I could do it. Vidas: For a long time I was amazed how you can do a trill with 3 and 4 with your RH, and I kind of avoided this myself; and only now I’m getting better with 3 and 4. My technique is getting better, I mean. Ausra: Good! I’m glad to hear it. Vidas: So, we’re all making progress, right? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: So guys, keep practicing slowly, especially on mechanical action instruments. Ausra: And you know, if you are struggling with ornaments, I would suggest you learn to play the pieces without ornaments first. Because what I have encountered while working with other people, or remembering the early age of my practice, is that if I tried to play ornaments right away, I would never play them well; and I could never keep a steady tempo in the piece. Vidas: Mhmmm. Ausra: So, you need to learn your music right rhythmically, without ornaments first. And when you are fluent with the music score, with all the musical text, then add ornaments. Vidas: Strange, I kind of forgot how I first learned music. And nowadays I’m learning with ornaments, of course--everything at once; but this is today, after 25 years of experience. So maybe other people need to simplify things at first. Ausra: Yes. And you know, if there are some ornaments that you are not able to play well, then just avoid them. Because nobody ruins a piece so well as playing ornaments in a bad manner, or you know, too slowly. Because they need to sound graceful. They are ornaments. And if some of them are just too difficult for you, then just don’t play them. That’s my suggestion. Vidas: Good. I agree. Please, guys, practice like we suggest; it really makes a difference in the long run. And keep sending us your questions; we love helping you grow. This was Vidas. Ausra: And Ausra. Vidas: And remember, when you practice… Ausra: Miracles happen. By Vidas Pinkevicius

Whenever you see a sustained long note of the Baroque piece, it's a sign that a long trill can sound well here (even in middle voices). Remember those Dominant or Tonic pedal points? This idea comes from knowing that on many keyboard instruments back in the day (harpsichords, virginals, clavichords) the sound would fade as quickly as you struck the note. So if you added a trill on a long note, chances are this note would be heard for much longer - as long as you play that trill. Sure, not in every case you see those trills written in the score and organ sound can last indefinitely. But it's nice to add something extravagant in that style once in a while. Like a wig, really. By Vidas Pinkevicius

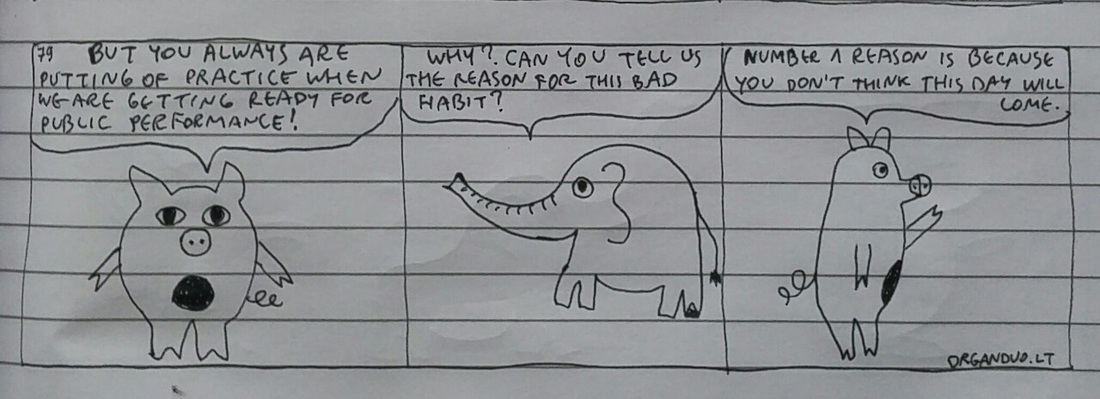

Some people like to practice their music without the trills. They say trills mess everything up. The rhythms become unstable, the articulation uneven. When the piece is already learned they go back and add the trills. The problem with this is not only the double effort required but also often incorrect fingering when playing without the trill. Another, more productive way is to practice trills slowly and deliberately counting repercussions. If you mess up, slow down even more. It is part of the piece and therefore needs to be learned at the same time as the notes. A trill is like a salt in a dish. Take it out and it lacks flavor. The other day my 6th grade student was sight-reading Bach's two-part invention No. 10 in G major, BWV 781 (hands separately). In the middle of this delightful little gem is an episode where the left hand plays eighth-note arpeggio figures and the right - long trills. Then the hands switch and the trill is placed in the left hand. My student had a difficult time playing those trills evenly. I have to say that there are many shorter mordents in this invention which my student executed fine (it was probably the result of our long-term study of Baroque music in historical informed manner). But the long trills were still a problem. If you play a similar piece on any keyboard instrument (including organ) - and there are many examples of long trills in Bach's music - my recommendation is to know exactly how many notes of the trill will fit in one eighth-note. Usually it's 2 or 3. Make sure you emphasize the beats so that you won't get lost with the trill. In the case of G major invention, I suggested 2 notes - basically the trill would be played in sixteenth-notes with a little bit of an accent on every other note. This practice makes the performance look slightly automatic but for a lot of people who don't have a good hand coordination it is very helpful at the beginning. After you get used to it, feel free to play it more musically and add more freedom. Ausra's Harmony Exercise: Transposing Sequence in C Minor: i-iv64-ii42-i Karl asks about the way to perform ornaments in Bach's music. He likes to hold a note longer than it is marked in the score and he is wondering if this is appropriate?

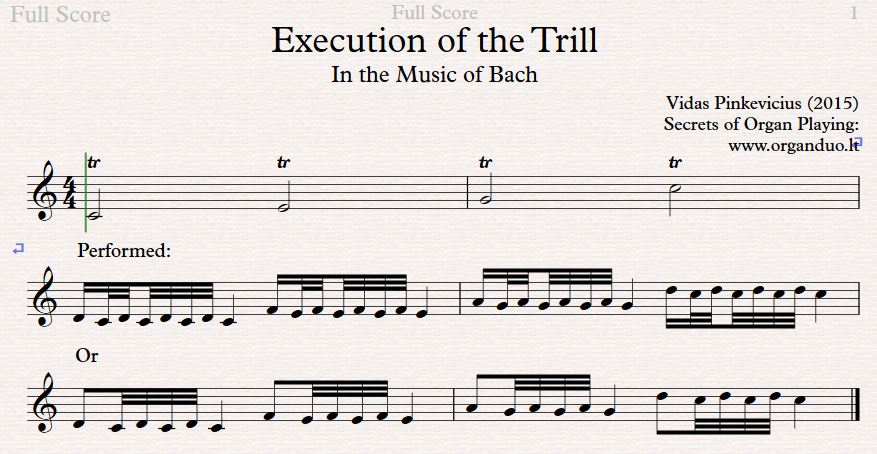

If I understand Karl's situation correctly, he is holding the first note longer than the rest of them in a group. I think this way is especially nice - in a trill and in certain other ornaments it sounds very natural to hold the first note a little longer and then speed up. Otherwise, if you play all notes evenly, it sounds a bit too automatic. And don't forget to start a trill from the upper note on the beat (not before the beat). This tradition of starting the trills from the upper note comes from the French music and since Bach was heavily influenced by the French tradition in various ways, he himself advocated ornaments to be performed in the French way (however, certain pieces which were written after Italian fashion might have trills which could be started on the main note). When Bach wrote the Klavierbuchlein for his nine-year-old son Wilhelm Friedemann, he included this table of ornaments (fashioned after the table by Jean-Henri d'Anglebert) which you might find useful to consult with. Note that the trill is shown to be executed rhythmically in 32 notes but in reality they would make the first note a little longer (like we do when we want to emphasize the downbeat of the measure in early music).. What about you? How do you play trills and other ornaments in Bach's music?  Vidas Pinkevicius: After yesterday's recital "Lithuanian Organ Music" dedicated to the 25th anniversary of the Baltic Way. On August 23, 1989 millions of people from the 3 Baltic states stood on the highways connecting Vilnius, Riga and Tallinn holding hands to show the unity of the Baltic people in their peaceful resolve to become independent from the Soviet Union. In the background you can see the famous Gediminas Castle which is the symbol of Vilnius, capital of Lithuania. That day the castle was covered by the the flag colors of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia (3 colors each). One of the most fascinating aspects of French Classical organ school is their ornaments. These ornaments, if performed right, add tremendously to the overall impact of the music. Without them, the music is much less interesting.

Today's piece for sight-reading is Fugue Grave (p. 4) from 5 Fugues et un Quatuor sur le Kyrie (1689) by Jean-Henry d'Anglebert (1629-1691). It's a four-voice fugue in the French tradition which normally didn't have any circle of fifth sequences. If you want to play the ornaments the right way, look at page 3 of this edition, where you will find the table of ornaments and their execution. As I played it this afternoon, I noticed right away that the most difficult ornaments to execute are in the middle parts (alto and tenor). The outer part (soprano and bass) are not easy, either. As you are focusing on these ornaments, don't forget to use articulate legato as people tend to forget it in difficult situations. Beginners can practice separate parts of this fugue. |

DON'T MISS A THING! FREE UPDATES BY EMAIL.Thank you!You have successfully joined our subscriber list.  Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas

Authors

Drs. Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene Organists of Vilnius University , creators of Secrets of Organ Playing. Our Hauptwerk Setup:

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

This site participates in the Amazon, Thomann and other affiliate programs, the proceeds of which keep it free for anyone to read.

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed