|

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start Episode 243 of Ask Vidas and Ausra podcast. This question was sent by Luciano and he writes: Dear Mr Vidas, Thanks for your reply. Apart the mini course I have a question /big doubt and hope you can clarify. -I found your article "Steps in Composing Organ Sonata " of 13/09/2012 and found it very interesting and clear: it is a kind of Template which I'm using with satisfaction (I'm Composer Amateur and write music only for my satisfaction). - Many years ago I studied the Book of Marcel Dupré :Cours Complet d'Improvisation à l'Orgue" and find something similar but not the same : it is a Binary form exposition I'm sure you know this book and -my questions are 1)are these Templates (yours and the one of Dupré the same thing or not ? 2) Dupré explanation does not mention a secondary theme (is he referring to a monothematic exposition?) 3) In the Dupré Book 1 Page 59 there is a General Plan of "his" Form But now I'm confused since there are substantial differences if compared with your Steps Thanks in advance if you will have time to clarify Luciano V: So what Luciano is studying Ausra I think is from from the first volume of Dupre’s Improvisation Method Book on the organ. It’s a free form. It’s not sonata form but improvisation on the free theme. Basically improvisation on one theme because sonata form has two themes. A: Yes, it’s especially necessary. If there aren’t two themes it means that the piece is not written in a sonata form. V: Yes, so what he sees in Dupre’s first volume the form is used mostly in french conservatory settings for examinations for prizes for contests they have at the end of the year for improvisation. This is a good method to follow if you want to improvise in a strict way to have a binary or ternary exposition. It’s a good starting point I would say. A: True. In general I would think that there is no need to compare these two different materials because they are completely different. Because you are discussing different forms. V: Yes, Luciano probably read my article about improvising or composing organ sonata which is of course based on real life works and they must have two themes or even more. A: Yes. Two at least, you have to have two but you also could have another two themes actually in exposition plus introduction. V: Right. So I think Luciano is in a good way to advance his compositional or improvisation steps and techniques. Do you think that composing and improvising techniques are similar Ausra? A: True. I think that one is based on the other. V: You are absolutely correct and right now I’m currently composing every day first thing in the morning on my Sibelius software and I have a midi keyboard connected to my computer and Sibelius has the function called flexi-time input. You can play on the keyboard while metronome is beating and the music will be notated on the screen right away. It can be done with as many as two adjacent staves. So what I’m doing is first I’m recording right-hand and left-hand parts then later pedal parts, improvising basically them. So of course in earlier times it wasn’t very perfect, this type of method of inputting notes because lots of syncopations, lots of strange ties and rhythmical discrepancies were always present because human hands don’t play very rhythmically. Right? But now with later upgrades Sibelius has various plugins you can clarify and update your score automatically afterwards. Sort of clean up. A: Yes it’s good that technology advances so fast. V: And so yes you have to do some manual work and editing but not nearly as much as before. So that’s how I am able to create quite fast those pieces in the morning and dedicate to my friend organists. So I hope guys you also are creating right, Ausra? We are also recording this conversation. It’s a form of creativity don’t you think Ausra? A: Yes. Some sort of form, yes. V: Because you can have various ways of expressing yourself. In texts, in pictures, in audio like we are doing, or in sounds, maybe you are playing some kind of instrument, or in video, you are videotaping yourself. Or doing it even live. Now you could do many kinds of streaming online, on Facebook, on YouTube. It’s all there after your done and your listeners will start to enjoy afterwards right away. A: That’s right, so just keep creating something. V: Ausra what would be your suggestion or ratio between consuming and creating. Let’s say organ music. Sightreading and creating. A: I don’t think it could be a ratio that would work for everybody. I think everybody has to find his own way. V: For Luciano, OK. A: I don’t know. He didn’t tell us so much about himself except that he is an amatuer composer. I don’t know if he intends to play his own works or not. V: But when you play other works of other composers of past or present or both, your knowledge increases, your musical taste increases, right? A: That’s true. V: Then you can express your ideas in a richer way. A: That’s right. But you know as I found out in the United States while studying that usually during your study years you try to play as much repertoire as possible, to study as much different various repertoire as possible. But after that you sort of narrow yourself down into one particular subject or one particular area. Do you think that’s a good thing? V: Well that’s the system we have now. Creativity is not a big part of our educational system currently but it doesn’t mean it has to be that way for everyone. If the school or institution or conservatory or university gives you some things to study it doesn’t mean that that’s the end of your education, right? You could study additional works and you could create your own things in your spare time in the mornings or evenings. Because yes, it needs to be supplemented because it’s not complete. Creativity is just beginning to be incorporated into the normal academic curriculum. A: Yes and now things are changing so fast and life, new technologies coming out every day, new discoveries. I think that creativity will be the basis to survive. V: Yes because machines will replace everything. A: True. V: And even creativity too, eventually, but not as fast as a year or two. A: Let’s hope for that. V: Yes. We all know there are videos of for example fake videos with President Obama saying something which he even didn’t say. Artificial Intelligence created that video based on the speeches that President Obama made in earlier times. A: Yes, that’s a scary thing, that somebody can analyze your speeches and then to create something out of those speeches. V: So the ratio, I intentionally asked Ausra about that because I read in one article online or even I’ve heard on the podcasts, I like to listen to educational podcasts while I’m doing some kind of other activity because it doesn’t take my time. So on one podcast, the podcast was called The Solopreneur Hour podcast and they told that the ratio between reading and writing had to be 3:1. If you write for one hour, you read for three hours. So it could be less or it could be more. Don’t you think Ausra that it could apply to organ? A: True. Three hours of playing repertoire and one hour of creating, improvising or composing. V: That it doesn’t have to be three hours, it can be maybe one hour of playing repertoire and twenty minutes of creating something. A: Seems fair. V: And then don’t forget to share, right? Because what’s the point of creating if you’re not sharing, if you’re hiding under the table. Thank you guys, this was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: We hope this was useful to you. Please send us more of your questions. We love helping you grow. And remember when you practice… A: Miracles happen.

Comments

AVA242: I love playing the organ but I never learned how to finger a piece so as to learn it well6/29/2018 Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start Episode 242 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. This question was sent by David. He writes: Hello Dr Vidas I love playing the organ but I never learned how to finger a piece so as to learn it well. I lack confidence in fingering and get frustrated. Will your online course help me? I am learning Bach’s Jesus Joy of Man’s Desiring which I received from your website. The other piece is by Alexander Guilmant---Offertoire from 18 Pieces Nouvelles op 90. David So Ausra, how can a person learn to make fingerings efficient in their organ pieces? Is there a shortcut to this? A: Well...yes and no, because there are some rules that you need to apply when playing early music and fingering early music; and you know, it’s different if you are playing modern music, or Romantic music. So what do you think about it? V: I think studying other people playing helps a lot--for example, whenever I record a video in slow tempo practicing any organ piece that I want to later create fingering and pedaling for and then send it to our team. I remember somebody commented that it helps not only for them to copy what I’m doing, but they also get a general idea about the principles, especially if that piece is familiar to them; and they also sort of grow in understanding how to create their own fingering, when they transcribe my video. A: Yeah, it’s true. Because I would say that you have to get a few pieces that are fingered by a master; and then, while playing/learning/studying those pieces, you will see--you will adjust to those patterns; and you can take them and use them in another piece. V: Mhm. A: Because after a while, you will see that some of the motives, some of the passages repeat themselves. And you will develop a sort of right habit of fingering correctly. V: Were you always good at fingering organ pieces? A: No! Definitely not! Because when I started to play organ, I had no idea what early fingering is. V: I remember when Professor Leopoldas Digrys at the Lithuanian Academy of Music asked me to create fingering for my own piece that I was playing--it might’ve been some Bach prelude and fugue. But I didn’t know how to do it, and I actually didn’t bother to learn. And I thought, “Why do I need this, if I can pretend that I’m playing with the right fingering, and then sooner or later my fingers will pick up the right combinations?” What’re you thinking about that? A: Well, I just think that our muscles have memory, too. V: Mhm. A: And it’s very harmful to play the same page, let’s say, of music, in a different fingering each time, because it will slow down your progress. But if you will play it a few times in the same fingering, it will make things easier, because your muscle memory will work. And while talking about the beginning of my organ studies--I remember I took one of the pieces (I think it was Fanfare) to America, and I remember when Pamela Ruiter-Feenstra looked at that score, and she asked, “Who wrote that fingering and pedaling?” and I told her that, “Oh, it’s my professor from Lithuania” (I won’t mention his name!), she just told me that it’s “better to just throw that score away! It’s really bad!” V: Why? Because Fanfare was a Baroque piece, right? A: True, but all the fingering was like in Romantic time V: And pedaling too. A: And pedaling, too. Lots of heels--that’s not suited to Baroque music, and you know, lots of using thumb on the black keys. V: I think it’s a good time now to mention a few principles that David could use in fingering and pedaling his own pieces. For example, if he is trying to create fingering and pedaling for an Alexandre Guilmant piece--Offertoire, right? What are the things that he could use? A: Well, you could use--of course, you need to play legato, pieces like this, unless there are indications not to do it. So you can use the heel in the pedal, in order to make the pedal lines move; and also you can use finger substitution… V: Finger glissandos? A: Finger glissandos, and you know, you can put your thumb… V: Under. A: Under, and things like this. V: But finger substitutions--just like feet substitutions, like toe-heel substitutions--are never to be used in all places, right? They probably have their own instances and rules. Do you need finger substitutions when you have just one voice? A: I don’t think so. V: I don’t think so, either. Everything could be played legato by using 5 fingers, if you have just 1 voice. A: But generally when I’m talking about finger substitution, I keep in mind a thicker texture. V: Mhm. A: That’s when you really need to use it. V: Do you really need to play all parts legato? A: Well...sometimes it’s impossible. Then it’s very important that your upper voice would be played legato. V: And the bass voice, too. A: True. But that’s the pedal. So now I’m talking about the manual part; because if you keep your soprano playing legato, you can create the illusion that you’re playing everything legato. That’s how things work on the organ. V: Right. So, what about early music? What are some things that he could use? A: Well you know, when you play early music, you need to think about your hand position, and about, you know...position fingering. V: What does this mean? A: Well, it means that for example, if you need to reach wider--if you have a wider leap, you will not be able to play it legato; you just have to move your entire arm to that new note. V: Slide from one note to another. A: Yes. And of course, you need to use articulate legato, so you need to use fingering that will help you to achieve it. Because if you will use modern fingering while playing Baroque music, you could still do that, I guess, but it would be much harder to achieve the right touch. V: Because you have to think about it. A: Sure. V: With early fingering, you don’t have to think about it. A: True. And paired fingering is especially good. It works well. And of course, no [heel] in the pedal part. V: And try to avoid using the thumb and the little finger in hands. Play with the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th fingers as much as possible, unless there are some thicker passages and keys with more than 1 accidental. A: That’s right. V: Okay guys. We hope this was useful to you. Go ahead and write some fingerings in your organ pieces, and don’t worry if you make a mistake or two you can always correct it later--adjust, right? Because we don’t always get it right at the first try. A: That’s right. V: Or the tenth try. A: True. V: Okay. And please send us more of your questions; we love helping you grow. This was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: And remember, when you practice… A: Miracles happen. AVA241: How one knows to play on the manuals or pedals if the notation is not the usual 3 staves?6/28/2018 Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

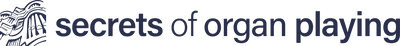

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start Episode 241 of #AskVidasAndAusra Podcast. This question was sent by Jan, and She writes: Dear Vidas, Thanks for answering my question. I was just wondering how one knows to play on the manuals or pedals if the notation is not the usual 3 staves. Now I know! Last question...does that then mean that organists also have the discretion of playing other early Baroque pieces (such as Titelouze) on manuals and pedals. I always wondered how my teacher knew what to play when there were only 2 staves and I was asked to play with pedals. V: It’s a complex question, right Ausra? A: Yes, it’s very complex. V: Remember in the 19th Century, Guilmant and other publishers at the time issued lots of early music editions, and many of them were with pedals…. Of early music, right? A: True. V: And today, when we look at that music with fresh eyes, it doesn’t necessarily mean they should be played with pedals. A: That’s right. But, you know, it’s a very complex question as to thought. You need to look at your complete piece of music, actually, and then to decide to play it with the pedal or not. V: And to look at the examples of the instruments of that time and of that period and of that area. A: That’s right, because the best thing would be to know for which organ the piece was intended, actually. V: Let’s say Titelouze, right? It was not like traditional French classic organ, right? Like Cliquot and Dom Bédos wrote about—it’s not like that. It was earlier examples, and of course, fewer capabilities. A: Sure! V: Especially with pedals. A: Sure! And then it depends on the piece. If you see that the bottom voice has many notes, so to say it’s virtuosic, then you will know it is definitely not suited for pedal. V: In general, long notes, such as cantus firmus or chorale melody could be played with pedals to make it more prominent in any voice. This means that if it’s in the bass, you could use a 16’ reed or an 8’ reed, such as a trumpet. If it’s in the tenor you could use an 8’ reed in the pedals. If it’s in the alto, what could you do then? A: Probably still would use 8’. V: But then the range… A: But yes, the range is… V: Maybe 4’ A: Maybe 4’, yes. V: Clairon, right? Or, not necessarily even reed, maybe super octave 4’. A: Yes, that could work, too. V: Or maybe for the soprano, cornet 2’ would work. It was rather common practice to play any voice in the pedal as long as it is a theme, like chorale melody, cantus firmus, and remember who wrote about that? Samuel Scheidt. A: Yes, in his Tabulatura Nova. The preface to his Tabulatura Nova, which comes in three volumes, I believe. So if, for example, we are talking about north German composers, baroque composers, then, of course, you have play the bottom line in the pedal. Because, if you would just look at the north German organs, and also organs in the Netherlands, they have such huge developed pedal towers, that it leaves you no doubt that pedal part was very important in that repertoire. V: Sometimes I even think that this practice could be applied in hymn playing, too. For example, if you have a four part hymn where the melody is in the soprano, you could actually learn the hymn setting in the way that this soprano part could be played with the cornet stop on the pedals. A: But isn’t it hard for you know, let’s say… V: Who said that it has to be easy? A: So now I’m talking about you are making life harder. V: I’m not making it harder for harder’s sake, I’m making it more interesting. A: True. But do you necessarily have to play soprano in the pedal? Is there no other way? V: It’s like transposing a piece in 12 different keys. Isn’t it fun? A: But couldn’t you play on the solo manual with the right hand to make that soprano line, and then alto and tenor in your left hand and the bass line with the pedal? Wouldn’t it be the same effect, but a little bit easier for you? V: Of course, you are right here, unless you want to use a specific stop in the pedals. Maybe you have a beautiful cornet in the pedals of 2’ pitch level, and you want to switch to a more colorful registration. That would be one of the possibilities. A: But don’t you think this cornet stop in the pedal is a very rare case, in general? V: Yes, of course it is very rare. But, maybe you will travel to Germany and play with the instruments there, you know? Maybe you will meet a local organist and he will invite, or she will invite you to try out the Schnitger organ, and what will you play then? A: Well, there are lots of repertoires suited to play on the Schnitger instruments. You could do any piece of Buxtehude, for example. V: Nobody likes my ideas—my crazy ideas. I see! Ok, let’s make it more simple, then. What about playing hymns in four parts, but with double pedals, yes? Yes, I like double pedals. The bass would be played with the left foot, chorale melody would be played with the right foot, and then you would need to add four more parts in the manuals. That would be a six part setting. A: Yes, but when I just imagine that to prepare for a service, it would take forever. I doubt that people have so much time to invest in one hymn. You could do it as an experiment. V: Yes, of course. Whenever I played this… I played some things like that, but I didn’t play for an entire month. I just practiced and see if it’s possible for one service. It was very challenging. But afterwards, my understanding of what’s possible really dramatically changed. A: True, but you know, if we are talking in general about for example Italian music or French music, I mean early music, you can almost avoid the pedal, or to do as little with them as possible. Don’t you agree? V: That’s what Samuel Scheidt wrote, also, in his Tabulatura Nova. Remember, all those pieces are written in two staves, so basically, it could be played with hands only. A: Yes, and it’s very handy, because then you could play them on the harpsichord, too, or only on the positiv organ that doesn’t have pedal. But if you have an organ with pedal, then why not use it as well? V: Right. And the only caveat is to look at the examples from the earlier times that that particular composer perhaps played, so that it wouldn’t sound strange in a modern setting with a modern organ. Thank you guys! We hope this was useful to you. Please send us more of your questions. We love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice, A: Miracles happen. Would you like to learn In dulci Jubilo, BWV 729 by J.S. Bach? I've created this score with the hope that it will help our students who love early music to practice efficiently and recreate articulate legato style automatically, almost without thinking. Thanks to Jan Pennell for meticulous transcription of fingering and pedaling from the slow motion video. Basic level. PDF score. 1.5 pages. 50% discount is valid until July 3. Check it out here This score is free for Total Organist students. Bellow is my practice video in slow motion: And analysis of the piece: Before we go into a podcast for today, I want to add that yesterday I forgot to share a video of Ausra playing Andante in D Major by Felix Mendelssohn, when I announced a score with fingering and pedaling so here it is now. Enjoy! Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

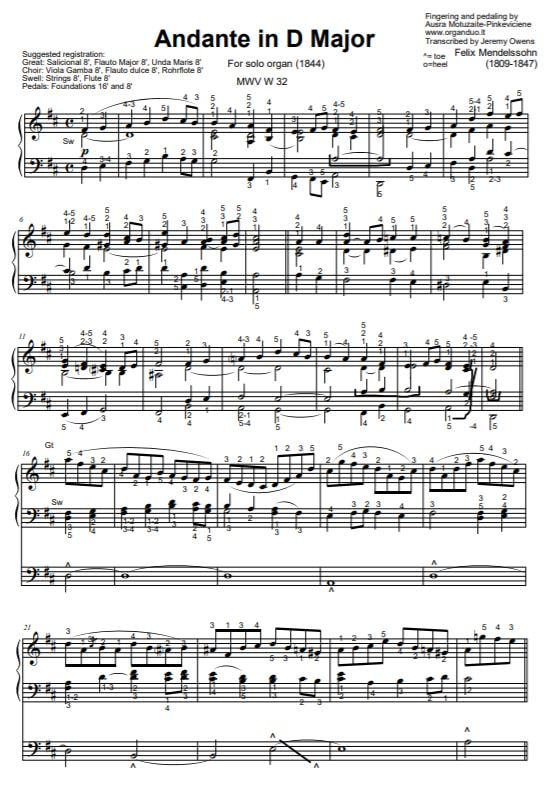

Ausra: And Ausra V: Let’s start Episode 240 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. This question was sent by Mark. He writes: Unfortunately I am not playing the organ at present due to a hand injury. I should be most grateful if you would cancel my subscription to Total Organist at present and not automatically renew my subscription when it becomes due. All being well I will rejoin your site once I am back playing in the future. V: I wanted to include this question about what to do if you have a hand injury. Should you postpone your playing, delay your playing, or is there anything you could do beside your hands. A: Well, if you have injury to only one hand you could still practice with another hand and of course your feet. V: I remember reading about Marcel Dupre when he was in his youth during one summer he injured his wrist and it was quite dangerous. A few centimeters off he would have cut himself to death. But luckily it wasn’t very serious but still he couldn’t use his hand so what he did, he practiced pedal playing entire summer until his wrist healed. And in his memoir he wrote that he played pedals with vengeance. Basically pedal scales and arpeggios and that’s where he developed unbeatable pedal technique. A: Yes, this accident, this injury could be thought of as a new possibility to improve your pedal playing. V: Yes, because it’s good dream for many people to perfect their pedal playing but a lot of people don’t even get around to this, right? Because they have so many things to do, so many things to play and they simply don’t have time for playing pedal exercises, right? But if you are in a position where you can’t play with your hands for a period of time, let’s say a few weeks or a few months even, right? You don’t know how long. Then that might be the ideal time to perfect your pedal playing. A: True, and since you still have another hand that you can use you could work in combinations too. V: Mark doesn’t write which hand he injured. A: It doesn’t matter because he can be both right-handed and left-handed so it doesn’t matter so much. But I think if you stop practicing at all through that time of healing it will be very hard for you to return back to playing. V: Yes, it’s not only like not practicing for a few months and your hands will become weaker, right? Or feet too. It’s not only that, it’s your will, right? You have to persevere. It’s difficult to even sit down on the organ bench in general, right? And if you leave that for several months and try to come back it will be even worse I think. A: Yes, but also you could draw a useful lesson from a situation like this because this situation shows how fragile the organist or any musicians’ life is. For example you could injure one finger, or lose one finger and wouldn’t be able to play again as you did before. So what I mean is that you need to have a backup… V: Plan? A: Yes, for example like I teach music theory but I can also play the organ. So in the case where I couldn’t play the organ, I can still teach. V: That’s right. In general I think organists are in a position to do at least three things. To teach, to perform, and to play in church services. A: Sure, and I would say also to conduct the church choir. I think it’s also part of organists job. V: Yes, conducting would include that too. But there are several other options that depend on your own interests and your skill set and your talents and even on your hobbies. Right Ausra? A: True. V: What is important is that you don’t stay for an extended period of time without creating anything, right? Because you will actually weaken your creativity muscles, so to say. So maybe changing medium, maybe it doesn’t have to be music for that time. Maybe see if you like other artistic ways to express yourself. Only you can know that but it’s important to immerse yourself in creating every day, at least for fifteen minutes a day, right Ausra? A: Yes it helps to be in good shape mentally and physically both. V: Excellent. So I hope Mark and other people who are struggling with hand injuries can still practice. The least they could do is to practice pedals. And in our courses we have Pedal Virtuoso Master Course which has complete set of pedal scales and arpeggios over one and two octaves and this will help you to perfect your pedal playing technique in twelve or thirteen weeks. So check it out if you haven’t seen this. Thank you guys, it’s really wonderful to receive all kinds of questions. It doesn’t have to be direct questions like in general we receive, but it could be like practice experience, it could be your feedback, it could be anything you struggle with. We try to find ways to improve, right Ausra? A: Yes, and by helping you to improve we actually improving ourselves too. V: Yes, it’s very selfish. We are very selfish. We are always helping ourselves. Because when we teach we think deeper about these questions, right? And how we practice, how we did in the past, right? For example, I also had a finger injury at one point, but many, many years ago and the easiest way out for my teacher would have been to just say “Oh, Vidas just skip practicing piano for three months.” But instead she gave me etudes for left hand because I injured my right hand and I played a few etudes for left hand alone for that period and I passed examinations in the school and practiced like everyone else. It wasn’t a vacation for me. A: True. And I remember reading about Maurice Ravel's’ friend who lost his hand in the war and he was quite a good pianist so Ravel actually composed a concerto for his friend for one hand so things happen in life. We just have to adjust I guess. V: I think the pianist was Paul Wittgenstein and he was an Austrian concert pianist and he performed Maurice Ravel's’ concerto for the left hand only when he lost his right arm during World War I. So there are always options to keep practicing, keep improving every day, right? A: True. V: That’s what we do. Thank you guys, this was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: And remember when you practice… A: Miracles happen. Would you like to play a beautiful and charming Andante in D Major, MWV W 32 by Felix Mendelssohn? It's a theme and variations on a very sweet melody. You will love it! 110 percent guaranteed! It's Ausra's favorite work by Mendelssohn. In fact, she first heard it play on our Vilnius University St John's church organ back in 2007 by the great Swiss organist Guy Bovet. We both fell in love with this piece at first glance. And last year she played this piece during our Fantasia Chromatica recital. But days before it, we came into the church to practice and I secretly recorded Ausra's performance from up close so that the hands were clearly visible. She wasn't very happy about it when she found out I made a recording because my filming interfered with page turning (I held the camera with one hand and with the other turned pages). And I think I missed one or two page turns... But now she is no longer upset because this recording allowed Jeremy Owens transcribe the fingering and pedaling and produce a nice score for you. So here it is: 5 Pages. PDF score. Basic level. 50% discount is valid until July 2. Check it out here This score is free for Total Organist students. Bellow is the video from our Fantasia Chromatica recital. Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start Episode 239 of #AskVidasAndAusra Podcast. This question was sent by Koos and he writes: Hi Vidas, I am an organist that plays mainly organ in church services of a Christian commune in the Netherlands. Also I play at home on a classic digital organ, spiritual classics and music. Baroque and romantic. My biggest wish is that I can improvise. Although I do have time to practice I manage not to learn it. Apart from this wish I would like to be able to play better pedal; I make too many errors. I am searching for organ shoes, but can’t find them in the Netherlands. Also, I am learning to harmonize but that goes slowly. This is what I would like to pass on. Thank you for your articles on playing organ. Koos from the Netherlands. V: That’s a wonderful dream he has, right? A: True, yes. V: To be able to improvise, play better pedals, and learning harmonization. A: True. V: All those things will help one another actually. Harmonization will help to improve improvisation. Improvisation will help improve harmonization. And pedal playing will help to improve improvisation as well. A: Yes, because all these things are related between them. Yes, I would like to answer his question about organist shoes a little bit. I would say you know that if you cannot find real organist shoes you can buy other shoes as well because you could adjust them. Especially for men it shouldn’t be hard to find organ shoes because so many classical men’s shoes are suited to play the organ. V: You just need to check the heels, if they are even and not rubber and not plastic but probably leather. A: Well you cannot find often leather shoes. V: Souls. A: Souls, yes in just a regular store. But it wouldn’t be a problem if they wouldn’t be leather because for many, many years I played with no organ shoes and I played well. I played trio sonatas by J. S. Bach just having regular shoes. The front of the shoe needs to be not too wide so that you wouldn’t hit two keys instead of just one and the heel of organ shoes for women for example needs to be not too thin that it would slide off the pedal. V: Right. A: Yes, but sometimes people think that if you can access and get real organist shoes that all your pedal problems will be solved but that’s just an illusion. What do you think about it? V: Can’t they invent organ shoes that play themselves? A: (Laughs) That would be wonderful but you can just press a button and play a recording for service for example and just read a newspaper or surf through your phone. Actually I have seen things like this especially in the province. V: Ohh. What do they do during the service? A: Well it was not for service but I think for a wedding. V: I see. They press the button and then music will sound through the loud speaker system in the church. A: Not necessarily but sometimes an organist would bring a recording player with him and just cheat from an organ loft. V: And it sounds like real organ but it’s not. A: I know because acoustics are often so good in our churches but that’s not a nice thing to do so don’t do it. But I hope I convinced you that having real organ shoes is not a need. V: Some people play even without shoes and manage to play pedals quite well. About improvisation Ausra, Koos wishes to learn improvisation but he writes that although he has time to practice somehow he doesn’t see improvement. A: Well maybe he could combine learning harmonizing improvisation because this might be a problem that he does not know how to harmonize or what certain chords mean, how to make them, how to connect them. V: You’re right. There are several ways to go about improvisation and one of them is going through the basics first. Basics would be chords, learning chords and chord progressions and harmonizing them in four parts but at first it’s not easy because you have to learn voice leading and avoid parallel fifths, and maybe octaves and augmented intervals and other various rules in classical harmony. So what would be the easier way to learn harmony and then improvisation? Is there a shortcut? A: I don’t think so actually that there is a shortcut. V: Answer this Ausra. What would your answer or suggestions be to your younger self if you could go back in time maybe twenty years or not twenty years maybe twenty-five years? A: Well when I was at school I learned harmony very well actually extremely well. I could play modulation sequences, all type of cadences, in various keys just caused me no problems. But nobody taught me to improvise and nobody taught me to use these things in my practice. V: Although you had some keyboard harmony experiences right? When you had to play on the piano and your teacher would listen to you. A: I think this was a sort of crucial point. At that point I would try to improvise and somebody would teach me to improvise. I think I could do that very easily because I had such a great knowledge of theory and such good basics. V: Now you are teaching harmony for many years, right? A: Yes. V: You cannot say that you lost this skill right? You actually improved this skill to the level that you are an expert in this. A: But I think it’s always easier to start things and to do things when you are young. The younger you are the easier it is. Through the years it becomes harder and harder because when you study something you have more time for that and after that you have to learn how to do other things, you have to learn how to support yourself and money and all. V: I know what you mean. A: You have less and less time through the years. V: So learning as a child is much better than learning as an adult? A: True. V: What if Koos is not a child anymore and of course he is not a child anymore. Can he improve? A: Sure you can improve at any age except that your progress will be probably slower. V: It depends, right? It’s different for every person and since Koos cannot compare himself to Koos in the childhood. He only has this opportunity to practice today. So there is only one option, sit down on the organ bench at home for example or in church and just play. A: True. And you know if you have no time or patience to learn all the harmonic voice leading rules first, but you still want to learn to improvise and to improvise soon what you could do is study easier compositions by composers such as Bach for example. What I would do if I didn’t want to learn theory a lot I would take Prelude No. 1 from the Well Tempered Clavier by J. S. Bach. I would write down myself progressions, it’s not so hard to analyze them and then try to play it maybe in another key or try to play it by looking at the chord progressions not looking at the score myself. Then maybe I would pick up one idea from Bach and let’s say another idea from Pachelbel. Maybe I would take progressions from Pachelbel and texture from another composer and try to mix things. V: It’s an interesting thing you mentioned Ausra. That’s exactly how I created Prelude Improvisation Formula. From the preludes written in the Clavierbuchlein for Wilhelm Friedemann Bach and actually the C Major Prelude, the earlier version, is in it too. And I would analyze and find figures, patterns, that people could practice and give them different cadences, different chordal progressions and different tonal plan to make it a different piece, unique. In major and minor and they can transpose of course. It’s the same system you can apply it to any composition that you want. I applied it to Bach’s style but it works for any creative way you want to express yourself. A: Yes. V: So you basically have to learn as many “tricks” and put them into your pocket basically and later take out at a certain time and to use them. A: That’s right. V: Thank you guys. This was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: We hope this discussion was useful to you and please apply our tips in your practice. We know it helps us and we hope it will help you. And remember to send us more of your questions because we love helping you grow. And sit down on the organ bench today before you go to bed because when you practice… A: Miracles happen. Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start Episode 238 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. This question was sent by Prince. He writes: I’m Prince from Ghana....l wish to become a great organist in future but my problem is my family can not afford to buy me an organ so l move from church to church playing the organ and l also cannot practice everyday because l don't have the organ in my house so my organ playing does not improve... So, having an organ (or any type of instrument) at home is a great privilege, Ausra, right? A: True, yes. But unfortunately not everybody can afford it. And if we are talking about organ--how many years ago did we get our organ at home? 10 years ago, probably? V: When we returned from the States. A: But not right away. We did it not right away. V: Mhm. A: I think this was like about 10 years ago, only. And at that time, we already had established careers, you know, and had our doctoral degrees. So before that, since my childhood, I had only a piano at home. And as for organ, I always practiced organ either at the Academy of Music or at church; and I did a lot of mental practice, too. What about you, Vidas? V: When I was growing up, I of course had a piano at home. And then, this piano had a feature that it had a middle pedal: you could press that pedal, and the sound would be quite soft. Or very soft, actually--I think too soft, for that instrument. But the good thing about that was that I could practice late at night, and nobody could hear me! A: I didn’t have such a pedal, so I would always have to practice at home during the daytime, because otherwise I would just bother my neighbors, and people would be complaining! So it’s not an easy thing to do when you are trying to become a professional; but that’s life, and you have to adjust. It only means that when you finally access an instrument, you need to make your practice as efficient as you can. V: What do you mean? A: Well, every day, know what you want to improve. What you want to do with the piece you are practicing. Or you know, with your technique. V: So, right now for example, we have an organ at home, and we can play whenever we want. A: But before that, you know, there were many years without an organ at home, or for example during our doctoral studies in the States… V: Mhm? A: We didn’t have any instrument in our apartment. Because we just rented an apartment, and didn’t have any instruments. So we did all the practice at school or at church. V: So, finding an organ or a church would probably be the #1 option for Prince. A: True, true. V: Or people who are in his shoes. A: Or maybe to get access at home to any type of keyboard--not necessarily organ, because organ is so expensive. V: Maybe it’s a temporary solution to buy a used electronic keyboard. And they could be quite expensive-- A: True. V: Used, you know, not new. Maybe not in perfect condition--you don’t need that. It’s just for practice, and it’s just temporary, until you will find something at least better or until you can afford to invest. Until you become a professional and you will have some savings, or you say to yourself, “Okay, I’m a professional at this, I have to have good practice tools, like a carpenter would buy good trade tools, and plumbers,” right? If they are professionals. But at first, if they are just starting out, they don’t know if they will be professionals or not, so they just probably use whatever they have on hand. A: And you know, Prince mentioned that he practices at church. V: Mhm. A: But not every day. So maybe for now, try to reach such a thing that the church would allow you to practice every day. And you know, do something nice back to the church that they would want to let you in to practice. Volunteer. V: Volunteer, or give donations. A: Well, as I understood, Prince’s family cannot make donations--they cannot afford to have an instrument at home. So then, volunteer for the church. V: Yeah basically--you either donate your time or your money. A: In this case, you will have to donate your time. V: Right. Whatever you have more of in your hands. And if you don’t have time and don’t have money--some people have that, right, Ausra?-- A: True. V: What does it mean, then? A: That either you don’t know how to plan your time, or you know, practicing organ is not so important for you. V: Or that other people are exploiting you. A: Yes, that’s also true. V: And you don’t know how to say no. A: True. V: So you have to learn how to say no to things that don’t really matter to you. Because otherwise, you will end up doing only things that matter to other people. I mean, it might sound quite selfish, Ausra, what I’m saying now. But I’m not saying from the selfish perspective, I’m saying from the perspective of an artist. Right? And artists need to find solutions how and when they could improve their art. Right? It’s a priority. I know, I know, I know what you mean, because for many many years I didn’t know how to say no to people, when they would ask me to do some favors for them. A: Mhm. V: And you know, for a while, I just felt exhausted after making other people happy, and working for them. But you know, then I realized that I would not be able to do anything for myself, or even rest enough. And that’s not good, actually. V: Yeah, you live only once, I think; and this saying-no skill is very very important, especially later in life. Maybe in youth, people can say yes to many many things, try out as many things as they even can, to find out what their true focus in life is, because not too many people know right from the beginning... A: True. V: What their mission in life is. But once they know the purpose, they must grab that purpose and never let it go. So, that’s what Prince should do, too, I think, with the church. Volunteer, maybe playing once a month for them. If he can play, you know--if he’s in this level of church service playing. A: True. V: Mhm. If not, he has to improve first, get experience. A: And of course, there are other jobs in church that you can do as a volunteer. V: Yes, definitely. A: Greeting people before the service and after the service, usher, acolyte and all other things. V: So basically, really become an indispensable member of the community, right? A: That’s right. V: So that people would miss you if you didn’t show up in that church. A: And then you will have access to an organ all the time. V: Right. It would be a very natural thing, if you just ask them, by that time, when you do for them so much that they would say, “Of course! Why didn’t you ask us before?” Right? A: That’s right, yes. V: “You’re doing so many things for our community!” And that’s the least expensive way to get access to the organ. A: Yes. V: Make friends from the local community, and help them. Be helpful. A: True. V: Okay, guys. We hope this was useful to you, because many many people don’t have an organ at home, right? I recently found out that one of our colleagues has an organ at home, but she said that since the time that she bought that organ, she’s practicing less and less, actually. A: That’s a paradox, but it often happens. Because you know that you can play any time, as you wish, it prevents you, actually, from practicing. V: Yes. It’s a great privilege to have access to the organ all the time, but it doesn’t guarantee you that you will sit down and practice. A: Yes, you have to have motivation. V: And motivation comes from knowing that your time is very very limited. A: True. V: Thank you guys! This was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: Please send us more of your questions; we love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice… A: Miracles happen. Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas!

Ausra: And Ausra! V: Let’s start Episode 237 of #AskVidasAndAusra Podcast. This question was sent by Jeremy, and he writes: I’m trying to speed up the Toccata from the Suite Gothique by Leon Boellmann. I am planning on playing the entire work for church in two or three weeks: Chorale and Minuet for Prelude, Prayer for Offertory, and Toccata as Postlude. I've played the Prayer a couple times as preludes or offertories over the past year. I've got the Toccata up to 100 to the quarter note. Any tips on speeding it up? V: So, this is one of the most popular toccatas for organ, right Ausra? A: It is! And probably one of the least complicated. V: People who want to start paying French toccatas probably would need to practice this, first. A: Yes, this is a good good piece for starters. So, how would you speed it up? V: My classical method of learning the piece, or any type of organ composition, up to speed is this: At first, I learn the music, if I cannot do this all parts together, then I do parts separately and then do combinations of 2 lines, and then three parts all together. How does it sound so far? A: Yes, it sounds good! The other thing that I’m thinking, is that because as was mentioned in the question, that there is not so much time left, actually. I don’t know if he will be able to push up the tempo a lot. But I’m thinking about the theme of this toccata, and for me, it seems that if he would compare various toccatas, this one is not as fast as some others, I would say. Definitely not as fast as, for example, Duruflé’s toccata from the suite. V: Right. I remember playing this piece when I was a student in the early stages at the academy of music in Vilnius. So, I presume that Jeremy, by now, can play the piece with all parts together. And he writes that he can do that about 100 beats per minute. So that’s good. So, if you can do, let’s say slowly, but all parts together, then the next stage that I suggest is to start playing at the concert tempo, whatever it is in your opinion, maybe 120, maybe not too fast, I think 120 is probably maximum, I would suggest, for people who have not played for decades, and many many instruments before—with not too much experience. A: True. V: So, play this piece in a concert tempo, but only a shortest fragment imaginable. Maybe one quarter note, one beat, at the concert tempo, and then stop. And then, you have to look and imagine what’s ahead one beat further. And then you prepare for that beat, and then play it also, very very fast. And then stop again at the next beat. And so you do, several times, the entire piece, but while stopping every beat. What do you think, Ausra? A: Yes! This is exactly your method, how you work. Not exactly my method, but it could work, I think, very well. V: What would you have suggested, Ausra? A: As I always have taught, a hundred times, I would work in combinations, I would find the places where I would place accents, correctly, and definitely I would sing the melody in the bass. This would help me. V: My method is for very patient people, right? A: True. And I don’t have such patience. V: Then, I would play a longer fragment—maybe two beats, and then stop. And then four beats, so basically one measure. Then two measures at a time. Then maybe an entire line, then two lines. Then one page, then two pages, then four pages, and then the entire piece, I believe. A: True. I think that’s also nice if you don’t have access to the organ all the time. If you have access to the piano. For this particular Toccata, it’s nice to play the hand parts, manual part on the piano, and then really to sing that bass. V: Hmm. Right. A: It would work, I think, Nicely. V: What’s the reason people cannot play fast. A: Well, lack of, probably, muscle strength in the fingers. V: Finger independence? A: Finger independence, coordination problem between hand and feet. It could also be some inner problems, like being afraid of a fast tempo, too. Some people are afraid of fast tempos. So, it could also be a little bit psychological. Because a fast tempo, we often think that it’s something very hard, and I think that this thought gives us more of a struggle. V: I see. A: Don’t you think so? V: Right. I agree with you, because speed is a very relative thing. A: True. And also, I think if you would listen to YouTube recordings, in many of those, there is such a fast tempo, if we are talking about toccatas or some other virtuosic pieces. But not everybody has to play at the same tempo, because if you are technically very capable, then yes, play it very fast—as fast as you can. But if you are making mistakes, if you are not ready yet, then you would sound comic, and you will just make people laugh at you. V: So, I think Jeremy can play 100 beats per minute in a stable tempo without making too many mistakes. A: Because, you know, sometimes when an organist is not ready to play in as fast a tempo as he or she wants, and he or she tries to do it, it sounds comic. V: Yeah. A: So, you need to take such a tempo that you could still be able to control things. V: Also, people who can’t play fast usually don’t practice much on the piano. Maybe I’m wrong, but it could be that Jeremy has an electronic organ at home. A: Could be also. You know, electronic organ doesn’t help so much. V: Unless they have some keyboard with resistance, Right? A: True. V: Which is quite rare. A recent innovation, I think. A: Because it’s hard to develop your finger muscles while playing electronic keyboard. V: Remember our friend Paulus, who works in St. Joseph’s parish, here in Vilnius? He actually complains sometimes that he has to play an Allen digital organ. A: Isn’t this Johannus? V: Yeah, Johannus, Yeah. But still, digital and very easy to depress keys, and then he has to play sometimes on mechanical action organs like at Saint John’s church or the cathedral. And whenever he comes over, he is very much stressed out about the strength needed. Right? So a real organ with real resistance is, I think, a beautiful thing. So I think people should spend as much time as possible playing on real instruments plus piano, too, because it’s a real thing. A: Yes. I agree. V: And then their technique will develop much faster, and getting up to speed will not be that big of a problem. Yeah? A: Yeah. V: So, guys, please apply our tips in your practice. We certainly know they work for us, and we hope it will work for you, too. And please send more of your questions. We love helping you grow. This was Vidas, A: And Ausra. V: And remember. When you practice, A: Miracles happen. [Listen to the audio version of this conversation here]

A: What about originality in organ improvisation? V: Good question. I think a lot of people start with copying others, in any medium--in visual arts, in poetry, if you write a poem, right? If you read a lot of poems by other poets, you fall in love with them, and you create something similar. So with improvisation it’s kind of the same: you try to copy the style of your favorite composers. And a lot of people try to imitate Bach, which is probably one of the last texts we should do, because he is so advanced! It’s better to imitate some of his students, right--or masters before Bach, if you want to imitate anyone at all. And I think this stage is good, because it allows us to learn the basics of compositional technique, or improvisation. I don’t feel there is much difference between improvisation and composition. Composition is just written down, on paper or with the computer, and improvisation is the same composition but performed at the same time as it is being created. A: But don’t you think that written compositions are more elaborate and, you know...better in some ways? V: It depends on how far you have advanced in expressing your ideas. If you can come up with new ideas fast enough, it would be advanced, right? Many people can play double fugues, or triple canons. A: Really? V: Yes. And it seems like a supernatural skill to people who are, for example, not musicians at all; or, look, nonmusicians even marvel that you are playing with pedals. Right? A: Haha. But I don’t think nonmusicians can appreciate a double fugue very well. I think only a musician can do it. Because if you don’t know it’s a double fugue, then why would it matter? V: Okay, maybe I went to far with this. Maybe other musicians, right? A: Yes, I think other musicians, yes. V: Who have never created before, but only played double fugues themselves. Right? Let’s say organists who played double fugues by Bach, and heard some organist improvise a double fugue. And it is possible, but it takes probably tens of thousands of hours of practice to do this. And I’m just wondering if there is a point of mastering that isolated technique--this is a technique, double fugue or canon or imitative technique--what matters is that you create something. For people who want to do this, this is the way to do this. And for others, they feel that it limits their expression. They don’t want to imitate any other style that they know before; they probably want to express their own unique (or not so unique, haha, maybe) musical ideas, right? Invent in the moment--whatever comes out. What do you think? A: Very interesting. Fascinating subject, actually. V: Why? A: Because there can be so many ways, you know, and so many ideas, how to go about something like this. Do you think sometimes it would be good to just compose some compositions first? V: Both ways. You can compose and improvise, and vice versa, right? It feeds off each other, right? We have talked about it before, I think. And it feeds your performance as well. It’s like a very good symbiosis--creativity and performance. A: Don’t you think that some improvisers could just compose a composition, write it down, and then learn it by heart, and to play, and then say it’s improvisation? V: Yes...but why? Why would they do this, if they could improvise a second composition maybe 5 minutes later? A: Well, I’m talking about not-so-advanced improvisers. V: Oh. A: Just, you know, beginners. V: I know. We’ve all been there. It’s a beginning stage: we are afraid of making mistakes when we improvise, so we write it down, and memorize. Or even, not write down, but maybe repeat, repeat, repeat, the same thing over and over, until we memorize it. I did that myself, and you can listen to it on YouTube, a few improvisations of my own from earlier times. And I’m not ashamed of putting them out there for people, because this is probably how other people might start. Not all of them, but some, definitely, who love to imitate other styles. I loved imitating Bach and Krebs, for example, at that time. And now I do something different. This is just evolution, I think. A: Evolution! I like this word. V: So, what did you do differently, Ausra, ten years ago, that you’re doing differently now? You surely also evolved! A: Hahahaha! Or I devolved, maybe! That’s also a possibility! V: Or revolved! Evolution or revolution! A: Yes. I think my life moved me in a different direction, a little bit--more in the music theory field. V: This is good, for your intellectual mind. A: Well yes, I guess it is. V: Before that, for example--before you were moved into the music theory world--were you able to analyze your pieces so well as you can do today? A: I was able to analyze, but probably not as deep as I can do now. V: Because you’re teaching others. A: True. But basically, while in these years of teaching music theory, I’ve lost the ability to speak, basically, because all I do is...I’m trying to teach others with as few words as possible. Because I realized if you tell your students too many words, they will not remember those. And it is quite a hard thing to do, to teach a new subject in only a few words. V: Do you sometimes encourage your students to teach less-advanced students in their class? A: Sure. I think that’s a very good way to learn. V: Their friends? A: Yes. And some people are just very natural about teaching others, and sometimes they find better ways and better words to explain things. V: So, you’re a teacher, right? You have students to teach who are less advanced than you. Do you feel that you’re a student yourself, today, even though you have practiced for many many decades? A: Well, yes, in a way because I still can find new things. V: And you can learn from either people who are more advanced than you, or music which was composed before. A: True, true, true. Especially from music. V: Or instruments. A: Yes. Because in studying compositions, you can see how those rules that you teach others apply to reality. V: Mhm. And do you feel that you have your colleagues who are on your own level? A: Well, you know, too bad that some of them are still...haven’t left the classroom, and they just stick very strictly to the theory books… V: Mhm. A: And don’t try to look beyond the horizon to real examples of musical pieces. V: But you’ve got me! A: I know. V: So, if I can say, we’re colleagues at this, too, right? A: True. V: So you have students, you have teachers, and you have colleagues, right? Like friends. A: Yes. V: So people who are more advanced than you, who are equal to you, and less advanced than you. And all three levels are very important to probably any person. A: True, true. V: Right? So, as a closing idea, would you encourage our listeners to go out and seek out those people around themselves? A: Sure, of course. Because it’s very important to have somebody whom you can teach, or help. Help, I would say--yes, that’s a nicer word, probably. And then, it’s always good to have somebody whom you can learn from, too. V: Mhm. A: So it goes both ways, I think. V: And people who are equal to you. A: True, true, true. V: On the same level. Who can basically support each other. A: Yes, you can support and you can share your ideas. V: Thank you guys; this was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: Please send us more of your questions; you see how far we can go from the original question to the ending of this conversation! But we do hope it was useful to you, and inspiring, at least in some way. And please write more of your feedback and experiences; we would love helping you grow and discussing that on the show. And remember, when you practice… A: Miracles happen. |

DON'T MISS A THING! FREE UPDATES BY EMAIL.Thank you!You have successfully joined our subscriber list.  Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas

Authors

Drs. Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene Organists of Vilnius University , creators of Secrets of Organ Playing. Our Hauptwerk Setup:

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

This site participates in the Amazon, Thomann and other affiliate programs, the proceeds of which keep it free for anyone to read.

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed