|

Vidas: And let’s start Episode 101 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. And today’s question was sent by Paul, and he writes that his challenge is mainly his age, because he is 75 years old. First of all, Ausra, isn’t that great, that people still continue to improve when they are at this age?

Ausra: Yes, that’s wonderful. Vidas: Do you think it’s too late to get better at this age? Ausra: I don’t think so. Vidas: Why? Ausra: Well, because I know some people who are 75, and they are very active, and are improving every day. Vidas: And there are opposite situations, where people are just staring at the TV screen all day long, and they get weaker and weaker every day. Ausra: Yes, I think some teenagers are older than some seniors. Because they just spend all day long playing with their smartphones and PlayStations and so on and so forth. Vidas: So, the fact that Paul sent us this question already shows us that he’s on the right path: basically, he has enough curiosity to improve himself. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: He is not satisfied with the current state, and he wants to get better all the time...Maybe faster than is possible, right? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: Maybe we should just basically support him, and inspire him to look at the situation from outside himself and really appreciate how far he has come. Ausra: That’s true. Because in general, I will be very happy if I live as long as to reach 75 years old; that’s a gift from life already, and it’s so nice that he’s still able to do things. Vidas: So, what helps? Of course, we’re not 75 years old yet, and we don’t know how people feel at this age; but general pointers could be: keep moving. Ausra: That’s true. Vidas: Keep being active, moving in terms of physically, and also mentally. Ausra: Yeah. Vidas: So mental practice is, of course, on the organ, very well. But also physical practice, as well. Ausra: That’s true. Do you think, Vidas, that practicing organ slows down ageing a little bit? Vidas: While you get older and older? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: I think it should, because your body gets a little bit weaker; but there are ways to postpone that process a little bit. Ausra: And do you think organ is a good way to help do it? Vidas: Yeah, especially because it’s primarily a mental activity. You’re looking at the symbols of music on a sheet of paper, which don’t mean anything to other people, perhaps; but you translate those symbols into meaningful musical ideas. So this is primarily a mental activity, which of course can just expand your mental capacity over time; of course that helps. Ausra: Yes, I personally strongly believe that organ may reduce the risk of such diseases as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s and multiple sclerosis--not to prevent them entirely, but to slow down the development of those; because while playing organ, you always have to basically use your coordination to coordinate your hands and feet, and look at the music; and it helps your brain keep moving. Vidas: Remember in our Unda Maris studio, we have a senior person who is maybe in her--I would say, maybe early 70s? She maybe started playing the organ not long ago, but she has trouble walking, right? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: She walks with the help of canes. And she enjoys playing the organ a lot, because of all those reasons, of course. It’s a good exercise mentally, and also physically. Ausra: Yes, that’s true. It’s better than sitting at the piano, because your feet are moving, too. That’s a great advantage, actually. Vidas: Yes. So don’t feel like you have stopped your progress, Paul, and others who are this age--maybe older. We have a lot of students who are even older, in their 80s, and even somebody who is 90 (or older) years old! So just keep practicing, keep getting better--1% of your efforts every day; and by the end of the year, you can look back, and you will see how you will have progressed a lot. Thank you so much, guys, keep sending us your questions; we love helping you grow as organists. This was Vidas. Ausra: And Ausra. Vidas: And remember, when you practice… Ausra: Miracles happen.

Comments

Vidas: Let’s start Episode 100 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. And this question was sent by Paul, and he writes that he is a slow learner. First of all, let’s celebrate, a little bit, our small achievement: 100 podcasts of simply helping people to grow in organ playing, answering their questions. Isn’t that great, Ausra?

Ausra: Yes, it seems so incredible that it’s already 100 podcasts. I don’t know how much we have to talk about! Vidas: When we first started, we didn’t realize we would go that far, right? It was supposed to be a limited number of episodes--maybe 10, maybe 20. Ausra: Yes, maybe 30, but not 100! Vidas: Yeah, people kept writing to us and kept asking these questions, and we were amazed, right? Ausra: Yes; and it’s really nice to help people, and especially it’s nice to receive a response to our answers. It’s very nice. Vidas: Yeah, and sometimes we put those nice letters we get into our folder called “Love Letters,” which is basically many thanks from people and encouragements for us to continue. So thank you so much, guys, this is really wonderful and we appreciate it a lot. Ausra: Yes, thank you so much! So now, let’s go back to Paul’s question. And really...what do you think he means by being a slow learner? Does he compare himself with somebody else? Vidas: Exactly. How do we know if we learn something “slowly” or “fast?” Ausra: Yes, how do we set those boundaries? Vidas: For example, let’s say a piece is 5 pages long, and we learn it in 1 month. Is it fast or slow? Ausra: So, I think it’s always a question mark… Vidas: Relative? Ausra: Yes, a very relative thing. Vidas: Do we advise people to compete with somebody else? Ausra: Well...yes and no. Because for some people, having that competition is a good thing, because it makes you to work faster and to develop necessary skills faster. But for other people, that competition might just simply destroy all passion for organ. Or anything. Vidas: I think the best competition is with ourselves, right? Ausra: Yeah. Vidas: Because we have to compare ourselves to ourselves yesterday, or ourselves a week ago, or a month ago, or a year ago. Only then will we know our true advancement, true level of how we progress, if we are on the right path or not. If we compare ourselves with other organists, who we listen to on YouTube or in recitals...as Ausra says, sometimes it is inspiring, but more often than not, it is discouraging, I think. Ausra: Yes. If, for example, we would have to compare our childhood experience in Lithuania and our experience while studying in the United States, what could you tell about all that--teacher and student relationship? Vidas: In Lithuania, there were several organ professors at the Academy of Music, and each of them had their studio organ class--maybe 5, maybe 6 people total. And generally, they were closed among themselves, right? They felt sort of a competition between other students of other professors. There wasn’t any atmosphere of collaboration in this kind of setting. Whereas in America it was completely different, right Ausra? Ausra: Yes; and in Lithuania, I always felt that all professors, no matter with whom you studied, would say negative things to you, like, “You did that, and that, and that, and that, badly!” Vidas: So that’s European--we have presenting problems... Ausra: Well, maybe not the European way, but Lithuanian, definitely, yes. Vidas: Ex-Soviet way, basically; because in earlier times, talking about negative things was very common, and not so much of optimistic, inspiring things. Ausra: So, how did you feel about it? Vidas: To me, I always wanted more freedom; so whenever somebody tried to push me, I kind of resisted, because my mind wanted to be free from those boundaries, and I wanted to explore myself all those musical adventures. So in that case, we had one organ professor, Gediminas Kviklys, who was the best, because he let us do whatever we wanted. Of course, by that time we were developed enough--and could be responsible enough--for our own progress. In America it was a completely different story, because it was so supportive and collaborative between organ studios; right, Ausra? Ausra: And that supportive atmosphere--telling good things, nice things to students--made you want to do even more, and to give yourself more, and to practice more, and to become the best. And it was very nice. Vidas: But other colleges and conservatories have different environments, because some of them are very competitive. Ausra: Yes, that’s true. Vidas: And I’m not sure how students get along in those organ studios, but they must feel some kind of competition, because they constantly compete in international and national organ competitions among themselves, right Ausra? Ausra: And that’s what I told you before: for some people it’s a very good thing, because they want to compete all the time. They want to feel that pressure. Vidas: Because they don’t have enough pressure from themselves? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: They have external motivation. Ausra: But actually, I don’t feel that I have to have that external pressure, because it makes me feel guilty all the time and just incompetent. Vidas: That’s true for me, too. I want to be free, and I want to do the things that I want to do. So, I then compare myself...with myself! Ausra: Yes, so like Paul said, be learning slowly--that’s your way to do it. And it’s ok. Maybe you will become a faster learner with time, maybe not. But don’t despair. Just keep doing what you are doing. And it’s much better to learn things slowly but correctly, than to learn them faster and incorrectly. Vidas: Of course, our daily efforts compound; and if you just get better one percent a day, the next day you also get better one percent; but plus that fraction of the percent you got better yesterday; and a week from that day, you get better also one percent, but also plus all those seven percent combined. So it compounds; and after one year--I don’t know, I have to do the math, but--it’s more than one thousand percent! Ausra: Definitely, yes. Vidas: If you do this. Ausra: What could accelerate your progress a little bit, maybe, is if you could find time to practice a day not once, but let’s say, twice; let’s say one time in the morning and one time in the afternoon/evening. That might do things faster. What do you think about it, Vidas? Vidas: It’s an excellent strategy, because our minds can only focus for so long without breaks. So maybe in the morning, for some time before you get tired; and then, you see, your day will already be a good day, because you have already practiced in the morning. You already did the thing that matters to you the most. And then, if anything happens and you don’t have time to practice in the afternoon or in the evening, it’s still a day not wasted, in this case. So early morning practices are always the best; and then if you can do a second practice, that’s even better. Ausra: Yes; so try that, and you’ll see if it works for you. Vidas: Yeah, it doesn’t have to be a very long practice, right? Maybe for half an hour before you take a break and continue--that’s completely possible, right Ausra? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: Thank you so much, guys, for listening to us, for applying our tips in your practice. It’s really a small milestone we have achieved, with 100 podcasts of answering your questions. Without our listeners it wouldn’t be possible. And keep them rolling--keep sending your questions to us, because we want to reach maybe another hundred, right Ausra? Ausra: I’m not thinking so far ahead, but...it would be nice! Vidas: But most importantly, we hope you'll do something with this advice. It really makes a difference. Excellent. This was Vidas! Ausra: And Ausra. Vidas: And remember, when you practice… Ausra: Miracles happen. Welcome to Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast #118!

Today's guest is Angela Kraft Cross, San Francisco Bay Area organist, pianist and composer. She graduated from Oberlin College and Conservatory of Music in 1980 with bachelor's degrees in Physics and Organ Performance. She then earned her Doctor of Medicine degree at Loma Linda University, where she subsequently completed her residency in ophthalmology. In 1993, she completed her Master of Music degree in Piano Performance at the College of Notre Dame with Thomas LaRatta, with whom she continues to study. Her organ teachers have included Louis Robilliard, Marie-Louise Langlais, Sandra Soderlund, S. Leslie Grow, William Porter and Garth Peacock. In 2001, she was awarded the Associateship credential of the American Guild of Organists (AAGO) after passing rigorous playing and written examinations. She has studied composition with Pamela Decker in recent years. Dr. Kraft Cross has performed extensively on both organ and piano, having given over four hundred concerts across the United States, in Canada, England, Holland, France, Hungary, Lesotho and Guam, including such venues as Notre Dame Cathedral, St. Sulpice and the Madeleine in Paris, Washington National Cathedral in Washington, D.C., St. Patrick's Cathedral and St. Thomas Church in New York City, Methuen Memorial Music Hall and Trinity Church in Boston, E. Power Biggs' organ at Harvard, and Westminster Abbey, St. Paul's Cathedral and Southwark Cathedral in London. She has been featured soloist with local Bay Area ensembles; Master Sinfonia Orchestra, Soli Deo Gloria, Sine Nomine, Masterworks Chorale, Viva la Musica and the San Jose Symphonic Choir as well as Seattle's Philharmonia Northwest Chamber Orchestra and the Skagit Symphony in northern Washington. In May 2014, Masterworks Chorale premiered her new choral work Solomon's Love. In July 2011, she was a featured recitalist at the San Francisco AGO Region IX Convention. She has released seven CDs; three with Arkay Records: two on organ (French Romantic and North German Baroque) and one on piano (Classical Piano Sonatas); and three with Compass Audio in Europe: (200 Years in the Germanic Tradition, the Majesty of Cavaillé-Coll and a 2CD set of Mendelssohn's organ works recorded on the 1801 organ of St Margaret's Lothbury, London). Three of her organ albums have received critical acclaim in The American Organist magazine. Most recently she has released a CD of her organ compositions entitled Sharing the Journey, recorded at Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels in Los Angeles. She has served as the organist of the Congregational Church of San Mateo since 1993, and is currently the Artist in Residence. She is also a staff organist at the California Palace of the Legion of Honor in San Francisco. In addition to her musical career, Dr. Kraft Cross retired in 2011 having worked for 22 years as an ophthalmic surgeon at the Kaiser Permanente Hospital in Redwood City, and now practices ophthalmology with the Peninsula Ophthalmology Group. Dr. Kraft Cross is committed to the musical education of young people, and since 1997 has been instrumental in organizing an annual Organ Camp for young pianists headquartered at her church. She is the founding director of the San Francisco Peninsula Organ Academy, a nonprofit organization formed in 2014 to support young concert organists with scholarships on short intensive overseas study trips. Dr. Kraft Cross also served as faculty and or performed in Pipe Organ Encounters in San Francisco 2005, San Diego 2012, and Stanford 2013. She is the Regional Coordinator for Education for Region IX AGO and a member of the executive board for the Junior Bach Festival in Berkeley. She is also a member of the Concert Artist Cooperative. In this conversation, Angela is joined by her husband Robert who records her performances. They shares insights about her practice procedures, her challenges, her organ recordings, her passion for Mendelssohn organ works and Germanic organ tradition and about her future project recording organ symphonies of Vierne. We have recorded our conversation at Vilnius University St. John's church before Angela's concert with San Francisco Viva la Musica choir and orchestra. Enjoy and share your comments below. And don't forget to help spread the word about the SOP Podcast by sharing it with your organist friends. And if you like it, please head over to iTunes and leave a rating and review. This helps to get this podcast in front of more organists who would find it helpful. Thanks for caring. Listen to the conversation Related Links: https://www.angelakraftcross.com http://www.sfpeninsulaorganacademy.org

Vidas: Let’s start Episode 99 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. This question was sent by Paul, and he writes that he doesn’t always have the patience for a highly systematic and laborious practice. So, that’s a common problem among organists, right?

Ausra: Well, I think for any kind of people this is a common problem. Vidas: What can we say? We don’t always practice systematically ourselves, right? Ausra: That’s true. Vidas: We’re humans, and we have weaknesses. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: I think the important part is recognizing our weaknesses, and learning from our weaknesses. But I think it’s unavoidable, sometimes, to make mistakes and do things that we regret later. Ausra: Yes, that’s true. Otherwise we would become robots and computers that could just program ourselves, and do systematic practice all the time. But that’s just life--it’s impossible to do, be a machine all the time. Vidas: What I think about organists who don’t always practice systematically, with patience, is that probably, they haven’t seen the results of systematic practice yet; and therefore, they haven’t been hooked on this. Do you think it’s safe to say so? Ausra: Yes, I think that’s true. But also if you don’t practice systematically, you still get some kind of results. Maybe not as good results-- Vidas: Not systematic results? Ausra: Yes, yes. Vidas: Maybe not quantifiable results. Maybe you practice sporadically, right? And you get better one time, but you don’t know if you will get better in time for your next public performance. Ausra: Yes. I think that public performance is that way which keeps us moving, actually. Vidas: Mhm. Absolutely. I remember the time when we came back from America, from our studies, and there were some months when I didn’t play in public--maybe 5, 6 months, maybe half a year. And I remember at that time, I almost didn’t practice, because there was no external motivation--no push from deadlines and things like that. Ausra: Yes, deadlines. This is the word that I most hate! “Due date,” “deadline”--ugh! Vidas: But it keeps us moving, right? Ausra: Yes, that’s true. Vidas: You don’t have to set external deadlines, right? But you can set internal deadlines, for yourself, for your own enjoyment. Ausra: Yes, that’s true. Vidas: For example, if you’re planning to learn a piece or two on the organ, give yourself a deadline by which time you can play through it. Ausra: That’s right. Vidas: And make a plan. Because in order to learn, let’s say, a piece which has 10 pages in let’s say 10 weeks, you have to learn one page a week! It doesn’t mean that after 10 weeks you will be able to play this piece in public, right? Because you need maybe 1 extra month to get fluent and even better at this. And so...But practices like this--you give yourself a plan, and you proceed step by step. Ausra: Yes, that’s right. So you just have to commit to do something--to learn a piece of music to play it in public. Vidas: So for example, in our case, we are preparing for a recital in what, 3 weeks? about 3 weeks, in November. And there are some pieces--really challenging compositions among our repertoire. And if it wasn’t for this deadline in November--yes, we would play together, we enjoy playing in organ duet, but it doesn’t mean that we would practice and get better on time. Right, Ausra? Ausra: Yes, that’s right. Vidas: So although you don’t like deadlines, you must be glad that this public appearance is coming up. Ausra: Yes, of course, it’s always nice to have that external push. Vidas: Because what--for this concert, we are learning new music, right? And we are slowly getting better at this. So I think for other people, too, our advice could be to find a chance to play in public. Ausra: That’s right. Vidas: A piece or maybe 2 pieces at a time. You don’t have to play an entire hour or thirty minutes of program at once. Ausra: Yes. So maybe make a tiny recital, play a fancy postlude after a church service. And never despair if practice will not go well that day, or you will be too lazy to practice; that’s just a perfectly normal, natural thing. You will do better the next time. Vidas: That’s right. And please send us more of your questions; we love helping you grow. This was Vidas. Ausra: And Ausra. Vidas: And remember, when you practice… Ausra: Miracles happen.

Vidas: Let’s start Episode 98 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. And today’s question was sent by Rivadavia, and she would like to play reasonably difficult scores at first glance with the least error. So basically sight-read, yes, Ausra?

Ausra: Yes, yes. Vidas: So, is sight-reading a useful skill for organists, do you think? Ausra: Very useful; for any musician, it’s a useful skill. Vidas: Why? Ausra: Because the easier you can sight-read music, the easier you can learn music, too. Vidas: So, if I can play a medium-difficult piece from sight without preparation… Ausra: Yes? Vidas: Then probably, amount of time required to master that piece, or any other piece, would be minimal. Ausra: I hope so, yes--I think so, yes. Vidas: So what’s the first step, in your opinion, to get better at sight-reading? Ausra: Well, to do it regularly, to do it on a daily basis--I think that’s the best way. Vidas: How much music should you sight-read regularly, on a daily basis? Ausra: I would say one piece is enough, but you must do it every day. Vidas: Depending on the length, it could be even an episode of one piece. Ausra: Yes, that’s true. And telling that it’s one piece, I thought it’s about a 1- or 2-page-long piece. Vidas: But of course, if you have a sonata or a symphony, so it’s maybe half an hour long; so one part would be more than enough. Ausra: Yes. Yes, that’s true. Vidas: What’s the biggest mistake people make in sight-reading efforts? Ausra: I think most of them just pick too fast a tempo at the beginning. And that’s a mistake. You need to be a genius to sight-read a difficult piece at concert tempo. Vidas: Remember, even Bach couldn’t sight-read everything. When he visited his friends, he had this tradition of getting to the harpsichord and picking some music, and sight-reading right away. And one time, he stopped and got stuck in the middle of one page… Ausra: Yes? Vidas: And repeated that page 3 times! Finally, he decided that it’s not possible to sight-read everything. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: So... don’t despair, right? Ausra: Yes, that’s right! Vidas: Because even Bach couldn’t sight-read everything perfectly. Ausra: I don’t think there is a magic trick that could help you to sight-read everything in a fast tempo without any mistakes. Vidas: Is it ok to sight-read not all parts together, but just one line, let’s say, with one hand? Ausra: Well, yes; if you have trouble playing a few voices, then just play one or maybe two voices. Maybe sight-read RH first and then LH, and then pedal part. Vidas: Of the same piece? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: That still works. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: In the long run, you’ll get better… Ausra: Yes, yes. Sure. Vidas: And you can do combinations of two voices later on. Ausra: That’s right. Vidas: So, I hope our students can take this advice, and apply it to practice. But it’s not very easy to apply to practice, because if it would have been easy, a lot of people would be doing this already. Remember in our school, I suggested our students to sight-read one voice of a Bach 2-part Invention per day--RH and then LH, in the same day. Ausra: I remember that, yes. Vidas: And basically no one did it. Ausra: Mhm. Vidas: For a few weeks--it was a challenge, a 30-day challenge--because there are 15 2-part Inventions, and I suggested to do this for 30 days. One day RH, second day LH; and then from the beginning, the second invention; and so on. But they couldn’t keep up with this. Somebody tried it for a few days, but they stopped. Ausra: Yes, people don’t have enough motivation and patience. Vidas: Do you think that’s the case? Ausra: I think so, yes. Vidas: So, how could we motivate people to try this really, for real--for a longer period of time, until they get to see the results? Ausra: Well, you need to take it just step by step, and trust that at the end of that long way, you will see the result. There is no such thing as immediate gratification. Vidas: For example, I have a habit now, that whenever I sit down on the organ bench, I first try to sight-read or improvise, or vice versa. Ausra: Hmm. Vidas: Maybe sight-read first, because the improvisation could based on that piece which I previously sight-read. So what I do is, I open up a collection of music, and I sight-read one piece. If it’s a long piece, I sight-read several pages, or a section of it. And then it becomes a habit; I don’t even have to think about it. I even sort of miss it if I don’t do it regularly. Ausra: That’s a good way to do it--to make it your habit. Let’s say instead of warming up, just sight-read something and then learn your music, work on your music, or on your hymns. Vidas: So for example, when you will be playing organ music of preparing for our recital (which will be in November today), what piece or which collection will you choose to sight-read today? Ausra: Well I don’t know, I have to think about it. Vidas: Let’s say, early music or Romantic or modern music. Which is more dear to your heart? Ausra: Well basically any music, definitely. Vidas: Mhm. But you don’t have to stick with just one style, right? Ausra: That’s true. Vidas: You can alternate. Ausra: I like to sight-read piano music, too Vidas: Mhm. that counts, of course. Ausra: That way I can expand the repertoire that I know, from inside out. Vidas: Yeah. So guys, you see it’s really possible to develop a habit of sight-reading unfamiliar organ music, and gradually get better at this. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: It’s a very valuable skill. Ausra: And also, while sight-reading, maybe you will enjoy some piece so much that you will finally decide to learn it. Vidas: Yeah. Ausra: So that’s a good way to build up your repertoire. Vidas: And broaden your musical horizons, too. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: So, please apply our tips in your practice. It really works when we apply it--it works on us, and we know that our students who apply this in their practice, of course, get better and better every time. And send us more of your questions; we love helping you grow. So, this was Vidas. Ausra: And Ausra. Vidas: And remember, when you practice… Ausra: Miracles happen.

First, the news:

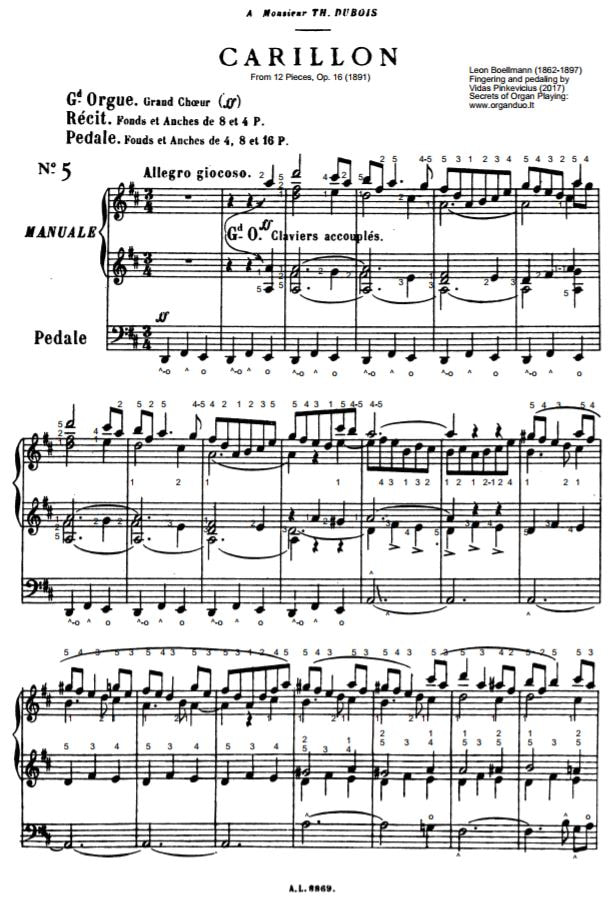

Would you like to learn the famous Carillon by Leon Boellmann (1862-1897) from his 12 Pieces, Op. 16 (1891)? If so, save yourself many hours and check out my new PDF score (5 pages) with fingering and pedaling for efficient practice to achieve ideal legato articulation. 50 % discount is valid until November 1. Free for Total Organist students. And now let's go to the podcast for today. Vidas: Let’s start Episode 97 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. And today’s question was sent by Rivadavia, from Brazil. And she has a problem that she doesn’t have enough time to practice. So Ausra, what do you do when you don’t have time to practice? Ausra: Well, I try to find time to practice. But whatever you do, if you know that you have a performance coming up, prepare in advance. Vidas: Imagine you work at school from 8 o’clock until 6 o’clock--or at least 4 o’clock, right? And after school’s over, you’re very tired. But you know your recital’s coming up. Will you be able to practice that day? Ausra: Well, sometimes yes and sometimes no. Vidas: Do you beat yourself up when you don’t practice that day? Ausra: Actually no, because sometimes you just have to rest, in order to practice well the next day. Because if you are too tired to practice, then it will not be a good practice. Vidas: That’s right. Ausra: And if it’s not a good practice, then I think it’s better to not practice at all. Vidas: You don’t have this inner feeling of frustration with yourself, like “Oh, you skipped practice, you’re a bad person and you will go to hell!”? Ausar: Hahaha! Sometimes I do get that feeling, but not always. At least when I cannot practice because I’m just too tired, then no, I don’t have that feeling that I will go to hell. But if I don’t practice because I am too lazy that day, then yes. Vidas: For example, today--are you lazy or are you tired? Ausra: Well, actually I have a cold right now, so… Vidas: You’re sick? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: Me too. So our voices are not in the best condition today. But still we can give you some pointers and tips and advice on how to behave in this situation, when you feel you don’t have enough time. For the most part, Ausra, do people really not have enough time, or do they say they don’t have time? Ausra: Hmm, could be both ways. Vidas: Both, right. You see, when a person skips practice, he gives a reason, right? And the reason for everybody to know is that, for example, Rivadavia doesn’t have enough time to practice. But the real reason might be something else, right? Ausra: Yes, that’s true. Vidas: I’m not saying that it is like this, but it often happens that we keep our most private thoughts and reasonings and excuses to ourselves, right? And what happens is, we want to look good in front of other people; and we say we don’t have time. Ausra: That’s true. I remember one show that we had in Lithuania a few years ago. There was one person from the bank who would teach families actually how to save money. And what she would do is, she would come to the family, and at the end of the week, all members of the family must supply her with receipts and checks and all those things that they had spent money on. And then she would make sure if all those purchases were necessary. And she would teach people how to save money--how to not get unnecessary things, and…save! So that’s what I think would happen with each of our schedules: if we would write down what we’ve spent time on, I’m sure we would find unnecessary things that we do. Vidas: There is an app--or a few apps, now--online, where you can check your online activities, what you’re working on on your laptop or even on your phone. And when people say, “Oh, I’m just checking my Facebook for a second,” or just text or email, or look at a YouTube video for 3 minutes--what happens sometimes is that we don’t notice. We become so captivated by that activity, immersed, that we simply forget the passing of time. Ausra: That’s true. I think probably the worst time killer is a smartphone nowadays, with all its Facebooks and Twitters and all those internet sources. And of course TV too, for some people... Vidas: Mhmm, but I think online activities are getting more prominent. Ausra: ...Yes. Vidas: So you really have to be very strict with yourself, because only you can control yourself. No app can really change your habits, actually. It’s just a game with yourself, right? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: It’s a game. For some people it might be necessary to do this extraneous checking that you’re on the right task. But really what it comes down to is your inner motivation for each day--are you living fully each day, or are you not? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: With each moment, we have a choice, right Ausra? Ausra: That’s true. Vidas: For example, today: what we’re doing now, we could be doing with a thousand different things, right? But we chose to record this teaching video. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: Ausra, is it a wise choice? Ausra: I hope so! Vidas: Why? Ausra: I think it’s right to help somebody. Vidas: That’s right; we really hope our teachings can help you grow as an organist--and as a person, too, because it’s a total personality development, I think. So what you can do with the passing of time is to have a stricter look at yourself, with your activities first, right? Where your time goes. Ausra: Yes, that’s right. Vidas: What else, Ausra? Ausra: Well, I don’t know, there might be different possibilities how you could have extra practice time. Maybe get up half an hour earlier in the morning and do your practice, or do it during lunchtime. Vidas: Mhm. Those hours, or minutes, where nobody’s disturbing you with some tasks or activities, are very precious, right? Set some boundaries, because sometimes your coworkers will come up to you and ask you for something, or a friend might call you and ask for your attention. But if you turn off your phone at that time, or turn off notifications on your phone, then you’re free to do whatever you set out to do. And then you can focus for at least 15 minutes, and that’s good for starters, right? Ausra: Mhm. Vidas: If anything happens, you know that that day you already practiced and fully accomplished something of value for 15 minutes. Ausra: And of course, if you don’t have much time to practice, you must know in advance what you will be working on that day. Just pick 1 piece, or maybe even one spot--one page or half a page of that piece, and practice only that spot. Vidas: Right. Ausra, do you think that people should learn how to say “no”? Ausra: Yes, that’s true. Some of us just have too many activities. Vidas: Too many. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: Too many things to do... Ausra: Yes I know. Vidas: During the day. And not all of them are of equal value. Ausra: I know, I’m already panicking about my November schedule. Because I agreed to teach sort of a course, a seminar, for church organists, on harmonizing hymns. And then I have to play a joint recital together with you... Vidas: Mhm! Ausra: On November 18th. And then I also agreed to lead a concert, actually, as a musicologist, and to speak about keys--about different keys, and what they mean in music. Vidas: Interesting topic. Ausra: So yes, that’s a very interesting topic; but on top of that I have to teach twenty-seven hours each week, and to grade papers, and do all that stuff. So that will be a challenging thing to do. Vidas: Well, at least you know that these activities are worth your time, right? Those harmony courses for community organists. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: For church organists. It’s worth doing, probably. Ausra: Well, I hope so. Vidas: We hope so. What else? I think when you say “no” to something, you can earn the privilege to say “yes” to something that is of value to your goals, to your vision. And you have to have as strong vision for the future--what you want to accomplish in 3, 5, 10 years, as an organist, as a person. And each day, take those simple steps, and maybe get better at one particular area at least 1%; because it compounds over time. Ausra: That’s true. Vidas: Every day. So, this is our daily advice. And now of course, we will go to practice later in the day, because to give you advice and to not take that advice ourselves would be counterproductive. That would be lying to ourselves, right? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: So we will definitely practice for our upcoming recital today, too. And please send us more of your questions; we love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice… Ausra: Miracles happen. Would you like to learn the famous Carillon by Leon Boellmann (1862-1897) from his 12 Pieces, Op. 16 (1891)?

If so, save yourself many hours and check out my new PDF score (5 pages) with fingering and pedaling for efficient practice to achieve ideal legato articulation. 50 % discount is valid until November 1. Free for Total Organist students.

Vidas: Let’s start Episode 96 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. And today’s question was sent by Rivadavia, and she writes that she struggles with lack of memory. Ausra, is it a common problem for people, do you think?

Ausra: Yes, I think so. Vidas: Did you have any students, when teaching, who complain that they can’t really memorize things and pieces? Ausra: Well, not so much; but performance anxiety--I get more of that. Being afraid that during a performance they will forget the music, and they will stop. What about you? Vidas: Myself, I struggled a lot with memorization, and that was actually probably one of the frustrations I had with my piano playing, back in school. Because normally, we had to play recitals and concerts and exams from memory, several pieces. Ausra: Sure. Vidas: And I just wasn’t good with that. I could sight-read rather well; but when my teacher told me to memorize a piece of music in a week or so, I just didn’t know how to do this. Ausra: Yes. And I remember that I always started to memorize pieces too late, and then I would be worrying so much when an actual performance would come. And I still have nightmares at nighttime, that I’m playing a recital or exams, and suddenly I forgot my music! Vidas: You’re not alone in this. I think just a couple of days ago, I had this lesson with my piano student at school, and for I think four weeks in a row, I’ve been nagging him to memorize his piano pieces. And one of the pieces is 3-part Sinfonia in d minor by Johann Sebastian Bach. And he just can’t seem to force himself to do this. The easier pieces that he’s playing, yes, he’s getting ready, and can at least play episodes from memory; but the tricky polyphonic texture, I think he delays it, postpones it; it’s a procrastination thing for him. Ausra: Well, that’s just too bad. Vidas: But kids, small kids, they don’t have problems with memory. I have a second grader who cannot read music, but can play everything from memory just fine. Ausra: Haha! Vidas: So that’s the opposite! Ausra: Yes, that way it’s easier for him just to memorize pieces for him--so that he won’t have to look at the music score! Vidas: He looks at his fingers, at the keyboard, and he memorizes the positions at the keyboard. Of course, he doesn’t understand anything about what he is playing! That’s another problem. Ausra: Hahaha. That’s true; but that’s what kids and beginners do. Vidas: Yeah. So guys, if you struggle with this, know that you’re not alone. I haven’t met a person who in some way, shape or form, doesn’t struggle with memorization. And I think the problem might have something to do with a theoretical understanding of what’s happening in the score. Ausra: And I guess some people are just more gifted than others, because the types of memory that human beings have are so different. For example, you could have very good visual memory. And I envy those people. Because I have heard such stories: for example, one pianist, he would perform a recital, and he would turn imaginary pages for himself, because he could just see the score in front of him. So that’s just unbelievable. Vidas: Or Marcel Dupré, who’s famous for having played I think 10 recitals in a row from memory, at the Paris Conservatory--the cycle of the entire organ works of Bach. And each recital was paced every 2 weeks. So basically, he had to know a gigantic amount of repertoire under his fingers from memory. Usually pianists and organists can play from memory maybe an hour’s worth of repertoire; maybe 2 hours, right (if it’s a long recital). Maybe if they are touring, maybe 3 hours at the most, if they have 2 recitals of 90min each, you see. That’s the most they can do. But Marcel Dupré managed to play everything from memory, 10 recitals in a row. That’s kind of unbelievable. Ausra: It is unbelievable. Vidas: And he did that I think 3 times, one in Paris and then I think twice in America. But he didn’t enjoy that--I’ve read that he didn’t want to repeat it that many times. Ausra: Yes, I think that’s just too much. Vidas: It’s torture! Ausra: Yes, even for him, that’s too much. Vidas: But it’s like a marathon, right? A very long race. Do you know who enjoys marathons? Professor James Kibbie. I’ve had a wonderful podcast conversation with him about his Bach project: he also recorded the complete works of Bach, and I think also from memory. But not in a marathon session like Dupré; but over a period of time, maybe over a period of one year, when it was Bach’s anniversary. He went to Germany, to the famous historical organs, and recorded. So he writes that he likes to run marathons, right? Ausra: Mhm. Vidas: And this strenuous, continuous running practice helps him to focus for long-term commitment to long cycles, such as recording all the music of Bach over one year, you see. Ausra: That’s amazing. Vidas: It is amazing. So guys, if you’re struggling, remember that everybody else is also struggling; but some people find something that works for them, running a marathon, or something else. So keep looking for that golden bullet, and keep looking for things that work for you specifically. Right? But I think you have to understand--we have to explain to people, Ausra--do you think that they should mimic their masters and try to copy them? To be like Marcel Dupré or James Kibbie? Ausra: I don’t think so. I think everybody has to find their own way, because we are all so different. Vidas: Yes. So guys, please be yourself; that’s the only thing that matters. And remember, when you practice… Ausra: Miracles happen.

Vidas: Let’s start Episode 95 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. And today’s question was sent by Rivadavia. And she has a struggle with patience, and she writes that she lacks patience and even perhaps lack of memory, when she practices. So Ausra, do you think that people often lack patience when they encounter difficult spots in organ playing?

Ausra: I think so. Not everybody, maybe; but yes, I think that might be a problem for some people. So are you patient, when you practice? Vidas: Usually I’m patient enough to overcome difficult spots; but sometimes, yeah, I get into the trap of feeling frustrated, and then switch to something else. Do you think that people have to stick to the practice no matter what, or is it ok to take a break--take a drink, walk, stretch--and then come back? Ausra: Yes, I think it’s good to take a break, but I think it’s bad to quit practicing a particular piece; because a lack of patience might mean that when you find out that this piece will be hard for you to learn, you discover some hard spots, sometimes you just quit, because you don’t have enough patience. Vidas: Have you ever quit a piece in your life? Ausra: Well, let me think about it. Yes, I think that I did, way back. I think I quit one choral fantasia by Max Reger. Vidas: Oh! Ausra: But I think it was probably the trouble or a bad decision of my former teacher, because I think I was still too young and not experienced enough to learn such a hard piece. Vidas: That’s right. And I think I quit some piano pieces back in high school, because they were simply too virtuosic for me. So...when people like Rivadavia, for example, encounter a difficult spot, right, and they want to quit--what should they do first? How should they motivate themselves? Ausra: Well, that’s a good question. Very hard one. Vidas: What about simplifying the problem? Instead of climbing a big mountain, right--like you say, mastering a Chorale Fantasia by Reger--maybe mastering a smaller episode first? Ausra: Yes, that could be; but you need patience for that, too. Vidas: Or not even an entire episode, but a solo line, of RH or pedal line, of that episode. Ausra: That might be a good idea. Vidas: You see guys, I think a step-by-step approach is slow, but it’s very firm, and a very positive way to reinforce yourself in your goals. If you’re taking this step, and the next step, and the next, you’re surely moving towards your goal. Would you agree, Ausra? Ausra: Yes. The slow process guarantees you a good result at the end of it. Vidas: So why do people quit, if the slow, step-by-step approach works? Ausra: Because you need patience to work slowly, and not everybody has it. But it’s not necessarily related to organ practicing. If you have patience in one site of your life, you will have patience throughout your life, too. Vidas: Do you think that people quit when they don’t see results? Ausra: Could be, too, yes. Vidas: Because if they feel results--some kind of results, even basic results--they feel compelled to take action even further. But if they just keep spinning their wheels, then they think inside their head that it’s not worth it. Right? Ausra: Might be, yes. Vidas: They’re not getting anywhere. Ausra: So I think it’s a good thing not to pick up too hard pieces at first, and not to expect too much from yourself in a very short time. Vidas: And celebrate small victories. Ausra: That’s true. Enjoy small things. Vidas: Give yourself a treat, whatever a treat might mean for you. Celebrate every small step, because each small step will lead you to success, whatever success means for you. Wonderful. So, another part of this question is of course, lack of memory. So Rivadavia is struggling not only with patience, but with memory. What do you think is happening, Ausra, for her? Is she trying to memorize some passages and struggling? Ausra: Sounds like that. Yes, then just play from the music. You don’t have to memorize it, necessarily, if you are practicing organ. Vidas: True, because memory is not everything, I think. You have to read music... Ausra: That’s true. Vidas: And memorize only the pieces that you want to keep for a long time. Ausra: Yes, that’s right. Vidas: Wonderful. We will discuss the problem of lack of memory in the next episode. And for now, just keep up your practice. And remember, when you practice… Ausra: Miracles happen. Welcome to Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast #117!

Today's guest is composer, organist and choir conductor from New Zealand, Nigel Williams. During his student days he was a chorister at Holy Trinity Cathedral in Auckland. In his eleven years in the choir he developed an interest in composing organ and choral music. After graduating from the University of Auckland with a Master's Degree in composition he began a career as a music teacher. He was at the forefront of music education in New Zealand for almost 30 years having taught variously at Westlake Girls High School, St Paul's Collegiate School, Scots College, and Marsden School for Girls. He retired recently from the position of Director of Music at Mill Hill School in London (UK). Currently Nigel is musical director of the Tauranga Civic Choir for whom he is composing a large scale cantata style work for performance in 2019. He has always maintained an active life as a musician and composer in the community. In Hamilton NZ Nigel established a regional orchestra and jazz band festival for schools. Taking advantage of St Paul's Collegiate new Letourneau organ he established an international organ festival to further promote the playing of the organ in New Zealand. He was Director of Music at Hamilton's St Peter's Cathedral for several years and established choral scholarships to ensure a quality of choral singing at the Cathedral and establish an enduring link with Hamilton's Waikato University's Music Department. In Wellington NZ Nigel served as chair of the Wellington regional committee of the New Zealand Choral Federation. During his seven years as musical director of the Bach Choir of Wellington he enjoyed the opportunity of directing over twenty five concerts with an emphasis on the larger scale works of J.S. Bach. He was fortunate to forge a relationship with members of the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra which lead to the formation of the Chiesa Ensemble. Nigel's last concert with the Bach Choir was a complete performance of J.S. Bach’s Mass in B minor. In this conversation, Nigel shares his insights about his love for twelve tone technique, modal music and of course, the polyphony. Enjoy and share your comments below. And don't forget to help spread the word about the SOP Podcast by sharing it with your organist friends. And if you like it, please head over to iTunes and leave a rating and review. This helps to get this podcast in front of more organists who would find it helpful. Thanks for caring. Listen to the conversation Related Links: http://www.nigelwilliamscomposernz.com Nigel's music on Sheet Music Plus: http://www.sheetmusicplus.com/search?Ntt=nigel+williams&aff_id=454957 |

DON'T MISS A THING! FREE UPDATES BY EMAIL.Thank you!You have successfully joined our subscriber list.  Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas

Authors

Drs. Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene Organists of Vilnius University , creators of Secrets of Organ Playing. Our Hauptwerk Setup:

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

This site participates in the Amazon, Thomann and other affiliate programs, the proceeds of which keep it free for anyone to read.

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed