|

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start Episode 203, of #AskVidasAndAusra Podcast. This question was sent by Robert. And he writes: Hi Vidas ... Robert here again from Vancouver Canada: I'm at a point where I read well and have pretty good independence with hands and pedals. I seem to have trouble with arpeggios though, left and right hand. Basically it's doing the fast transitions to other chords (in the progressions) which are often in inversions. Any material you know of or from your own courses that really exercises a disciplined technique? Cost factor I'm fine with as this is something I'd really like to get " under my fingers " yet, so to speak. I'm just playing this material way to slow. Appreciate your or Ausras input! 😃 Robert V: So Ausra, do you know of any courses or sources for information about learning to play arpeggios? A: I’m sure there are plenty of sources, you know, how to play arpeggios well. But for, in order to do that you even don’t need any additional material. You could just do it on your own. Just pick up any key, for example D Major, and start playing D Major arpeggios. V: But then you need to know the fingers. A: Yes, you need to know fingering. V: And usually the fingering is very naturally understandable if you have some experience with chords. A: Yes. And you know, I’m sure you could find in a library, books that consist not only of arpeggios but basically in order to, you know, build up your technique. As kids at an early age we start to play scales, chords, arpeggios and chromatic scales. V: Mmm, hmm. A; In various manners. And these four things actually help build you, up your technique. V: In addition to etudes, right? A: Yes, yes. V: Mmm, hmm. So one source to look at while waiting for our material—we haven’t prepared such a course yet—but since you are in need now, you could look at Hanon exercises. And in part two, at the end of part two, they have scales and arpeggios you know, keys. So that’s all you need probably, for now. And if, while you are in Hanon collection, check out the previous exercises. In part one too, they are very, very good. The aim for Hanon is it to get perfect technique over time while playing on the keyboards only one hour per day. Because in the fast tempo, you can sight read entire collection—there are three parts—in one hour. I don’t know who can do this because it’s really, really difficult, the third part, I mean, but virtuoso pianists can. A: Sure. So, and for now, if you have trouble, you know getting right arpeggio passage in the piece that you are working on, make an exercise from that particular spot. And check if you are playing with the correct fingering. This is a very important thing. Then you will play it fast. V: What to you mean Ausra, do an exercise based on your piece? A: Well, take a spot that you cannot play well, V: Uh, huh. A: Where you are making mistakes, just a little excerpt of with it. V: Yes. A: And play it many times. Especially in the slow tempo first, check your fingering if it is correct. Then you know, increase the tempo. V: Like one or two measures, right? A: Yes. Like one or two measures. Then you can have fun with it — you can transpose it too. V: Ohhh. A: Into different keys. V: Right! And then, of course by that time you even memorize this fragment. A: Yes, and you know, especially what I do with arpeggios, you have to know on which note to lean. If it’s a short arpeggio then it’s enough to lean in one spot usually at the bottom of the note or on the top of the note, depending in which direction the arpeggio go. But if it’s longer arpeggio, last more than one, one, one measure, then you will do, will have to do another accent somewhere. So that’s what helps me. V: Usually those longer arpeggios are based on one simple chord, like C Major tonic chord, and they just repeat the, the first scale degree one octave higher, two octaves higher, three octaves higher. A: Yes. And even if you know, if you make text mistakes, maybe you don’t know what those chords are, those arpeggiated chords. And this is also a good way you know, to, to play piece better and to feel more secure with it, to know what theoretically what’s going on. V: You mean that playing arpeggios will help you to understand music theory too. A: Yes that’s right. That’s what I mean. V: Prepare for harmonies. A: Yes. V: Nice! Do you think that isolating those measures and playing them over and over again plus transposing them, probably from memory, would help you in improvisation? A: Definitely, yes. V: How? A: Because you would develop sort of muscle memory, by transposing excerpts like this, and at the beginning you might need to think very carefully and slowly about them. But in time, I think you will be able to not think so much about them and do it almost automatically. V: You will develop sort of a bag of tricks, right? A: Sure. V: That you could later use in your own improvisations. That’s of course, that will be in the style of other composers though, right? But that’s in principle the same technique that jazz players are doing. They listen to recordings over and over again and maybe now in the slow tempo and transcribe, the notes. They call them licks, those fragments. And they then memorize, transpose, and later reuse them in their own improvisations. A: Yes, and you know, I think now in the 21st Century, they are too concerned about being original. Because look at the history of, of, of music. You know composers especially at the beginning of their career, they copied each other. They learn from each other. And it wasn’t considered a crime you know, to, to, to copy somebody, or something. V: Mmm, hmm. A: So I think, why not, you know, take something that is good from those times, and do it nowadays, especially when we are talking about improvisation. V: Mmm, hmm. It’s, it's like language, because music is communicating in some form of language, which is not text based but sound based. So if you have a version of language that other composers used, and you like it, there is no crime in, in communicating in this language yourself, right? Or part of that language. First you will shape and adapt that language for your own needs, right, as you develop. Because, because, look, you will not only copy one composer, you will probably mix ten or twenty composers together. Don’t you think Ausra, that this way you will become original? A: Yes. V: This mix of, of ten or twenty. A: Yes, it’s still will sound like you, not like somebody else. V: Mmm, hmm. A: Maybe it will remind of somebody else but, but still it will be your thing. V: Because other people who are doing the same thing, maybe they’re copying other composers in that twenty group. Maybe some of the are the same like you are doing, but not all of them, and the mix would be unique. A: Yes, that’s true. So now going back to the course. First of all, you need to check your fingering, if it’s really comfortable and fitting the particular passage, playing a slow tempo, transpose it to the other key. V: And do it over and over again. A: Yes. V: Excellent! I think this will be helpful to people who want to expand their technique. And their creativity too. A: Yes. V: Thank you guys for listening. This was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: Please send us more of your questions. This is really fun to helping you grow. And remember, when you practice… A: Miracles happen!

Comments

Vidas: Let’s start Episode 127 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. Listen to the audio version here. Today’s question was sent by Lilla, and she writes:

“Thank you for all your advice about organ playing - especially the pedal virtuoso course that I am taking now. Regarding the arpeggios, is it OK to NOT to follow with both legs, when one foot is playing the highest/lowest notes on the pedal board? I keep my other foot on the note that I need to play when switching legs. For example, in case of B minor arpeggios, I keep my left foot on D while keep playing with the right foot upward and backward. (I followed your suggestion to use the F# minor pedal signs for B minor and it seems to work better).” Isn’t that great, that the f♯ minor pedal version works for b minor, Ausra? Ausra: Yes, excellent. Vidas: Sometimes you get advantages of discovering similarities between the keys and transferring one type of pedaling to another key, which works sometimes with sharps, sometimes with flats. Ausra: Yes, it’s nice. It’s really a big help. Vidas: And saves time. So, her question is about… Ausra: About body position, basically. Vidas: Keeping either one foot in place, or moving that foot, together with another foot, upward and downward. What would you say about that? Ausra: Well, I would say that most of the organ scores would suggest to keep both feet together. Vidas: But in the case of, let’s say, b minor, in the middle of the pedal part, you use both feet. But then, it goes very high. Then, you only need to use the right foot. What about the left foot, then? Ausra: It cannot stay in the middle, I would say. Vidas: I think so, too. Ausra: Because otherwise you might fall down on the pedal, if you will shift your entire body too much to one side. Vidas: It’s an unnecessary burden, I think. Ausra: Sure, yes. Vidas: And in general, it’s quite difficult to keep your balance on the pedalboard while switching directions. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: You have to push off with the opposite foot, to switch direction with your knees, in order to simply not hurt your knees, right? Ausra: Yes. And remember that you must feel comfortable on the organ. Not like on the couch at home--but still, you know, it shouldn’t hurt, and it shouldn’t be very much uncomfortable. And if it feels like that, it means that something might be wrong. Vidas: Should Lilla stick with the virtuoso pedal course, or would it be beneficial for her to supplement her menu with real organ music? Ausra: Well, definitely supplement it with real organ music, because you might get bored by playing exercises. Vidas: And exercises don’t get you real life experiences. Ausra: Sure, sure. Vidas: They’re isolated techniques which develop one certain aspect of your playing, of your skill. Which is good, but in real music, you need all kinds of abilities, right? Ausra: Yes, especially while playing organ, you also need to work on your coordination. Vidas: Mhmm. Ausra: And if you are only playing pedal all the time, your coordination might not be as good. So you need to combine all those practices: do some pedal work, and do some repertoire. Vidas: Maybe play a scale or two, or arpeggio or two, for starters--for warming up. Ausra: Yes, definitely. It would be a good beginning, you know, to warm up. Vidas: And with your fingers, too. Ausra: Sure. Vidas: Something technical. For example, I like to kind of...warm up with improvisation nowadays; because I can warm up, and slowly, gradually feel the keyboard. And the pedals too, because I improvise with my feet as well. What about you, Ausra? How do you warm up? Ausra: Heheh. I warm up with dictations--playing to my students! Vidas: “Eight measures!” Ausra: Because I have so many classes that I teach--27 a week!--so I get plenty of warmups, with my hands, at least. Vidas: Do you play this same dictation over and over again, the same day? Or do you have different ones? Ausra: No, I have different classes, so I play different dictations. Some of them--most of them--are actually 3-part dictations; but some are 2-part, and some have only 1 voice. Vidas: Do students like those dictations? Ausra: Oh, no. They hate them. (Most of them.) Vidas: Do you like them? Ausra: Well...yes! Why not? Vidas: And why do you like them and your students don’t? Ausra: Because I can have the music score in front of me, and they just have to write it down by ear, so that’s another story. And they are hard dictations, so I understand why they don’t like them. Vidas: Do they have syncopations? Ausra: Yeah, syncopations… Vidas: Dotted rhythms? Ausra: Suspensions, dotted rhythms, and all kinds of...things... Vidas: They’re like short musical compositions-- Ausra: That’s right. Vidas: Like preludes of 8 measures. Ausra: Yes, yes. Vidas: And sometimes they do sound like preludes, when they are 3 or 4 parts. Ausra: Yes, those 3-part dictations, you could play them as preludes. Vidas: Mhm. I would even say 2-part dictations sometimes sound convincing. Ausra: Yes, because they have like secondary dominants, and some of them even have modulations. Vidas: So, you teach your students the skills for real-life improvisation, I think. Ausra: Well, yes, but dictations are mainly meant to improve the pitch--musical pitch, hearing. Vidas: Mhm. To help them understand what they’re listening to in real life. Ausra: Sure. Vidas: And that’s not necessarily enough for creating your own music, right? Ausra: That’s right. Vidas: You have another class--harmony-- Ausra: Yes. Vidas: --Which is a transition between playing repertoire, listening to what you play, and then improvising--creating your own music. Harmony is sort of the in-between step, right? Ausra: That’s right. It’s very important, you know. Vidas: Good. So, Lilla should also supplement her exercises, too, with real music, we think. Ausra: Yes, yes. Vidas: Alright. What about...what about other pedal virtuoso exercises? I have, I think, not only scales there, but also arpeggios over the tonic chord, arpeggios over the dominant 7th chord, arpeggios over the diminished 7th chord; and even, I believe, chromatic scales with single voice and with octaves. So it’s a really comprehensive approach. Not too many people finish what they start, from what I read; but those who do, thank me later. And thank themselves, too. Ausra: Yes. Excellent. Vidas: So, if you have the stamina to succeed, if you really want so badly to develop your ankle flexibility like Marcel Dupré taught, so then playing scales, arpeggios--with one foot and both feet--is very beneficial in the long run. But you have to not forget the real music. Ausra: Yes, definitely. You know, the real music is the most important, I think. All these exercises, they supplement the repertoire very well. Vidas: They are servants for repertoire. Ausra: Sure, yes, yes. Vidas: It’s not the goal to master those exercises. It’s a means--it’s a tool. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: They have to serve you. And if you don’t enjoy playing technical exercises, don’t play them. Right? This is for people who do enjoy them, like Lilla and others--hundreds of others, actually, who love isolated technical exercises. But other people cannot stand them, so they do something else. We need to always find a balance between what we can be passionate about, right--and what we can do long-term. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: Thank you guys, this was Vidas. Ausra: And Ausra. Vidas: Please send us more of your questions; we love helping you grow. This is really fun. And remember, when you practice… Ausra: Miracles happen. #AskVidasAndAusra 123: How to execute the B minor arpeggios of tonic chord over two octaves?12/8/2017 Vidas: Let’s start Episode 123 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. Listen to the audio version here. This question was sent by Lilla and she writes:

“Hi Vidas, could you explain/make a video of how to execute the B minor arpeggios of tonic chord over two octaves? In particular, the low f# is marked to play with the right heel. And also, I need to support myself with my hands keeping on the bench (not on my lap). I am not sure how to change this to keep my balance without hand support. Thank you for your help!” So, playing arpeggios with feet. It’s not very easy, right Ausra? Ausra: Yes, that might be tricky sometimes, yes. Vidas: But I think it’s very beneficial in the long term, because it will develop your heel flexibility, yeah? Ausra: Yes. But from what I understood from her question, she places the heel on the low F♯. Vidas: Mhm. Ausra: I wouldn’t do that. Vidas: Yeah, because… Ausra: I don’t think it’s possible to hit the low F♯ with the heel. Vidas: She is studying from my Organ Pedal Virtuoso Master Course, and in that particular arpeggio in b minor over 2 octaves, I probably made a typo: on the low F♯, I placed the heel. So obviously, it has to be-- Ausra: Toe. Vidas: Toe. On any F♯s, you need toes. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: So, this means that you could actually play the b minor arpeggio with the pedaling indicated to f♯ minor, which is R-L-R, then L-L-R-R-R, R-R-L-L, and L. So, to clarify that, B would be played with right toe, the low F♯ with left toe, B again with right toe, D with left heel, F♯ with left toe, then B with the right toe, D with right heel, F♯ with right toe, and then backwards: D right heel, B right toe, and then F♯ with left toe, then D left heel, and the last note B with the left toe. So...is it complicated, Ausra? Ausra: Yes, yes. It seems very complicated when you are telling each note so slowly. Vidas: Yeah, I don’t want to make a mistake, telling people what not to do! And the other part of the question was that Lilla is not comfortable sitting on the organ bench and playing, right? Keeping her hands on the bench, while playing without the hands, on the pedals. How to change the position and keep her balance without hands. Could you help her with that, Ausra? Ausra: Well, I hope so. Maybe she’s sitting in that position--I mean, maybe the bench is too close to the keys, or too far away from the organ. That might be a problem, too. Vidas: Basically, the rule to change position is to always face your knees to the direction of the pedals that you’re playing. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: If your pedals are left and your knees are facing right, you will easily damage your knees, right? Ausra: Yes, that’s right. Vidas:So, how can you push over with one foot? Is it difficult, Ausra? Ausra: Well, not so much, I would say. Vidas: Which foot do you use to push? Opposite? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: If you go upwards, you use the left foot. Ausra: Yes, that’s right. Vidas: If you go downwards, you use the right foot to push off, changing direction. Ausra: Yes, that’s right. And you know, if something feels very uncomfortable for you, it means that you are doing something wrong. It shouldn’t be torture, playing organ. Vidas: And I think it’s best to adjust the bench’s position, as Ausra says, so that you’re neither too high nor too low, neither too far from the pedals nor too close to them--and actually, sit on the edge of the bench. Ausra: Yes, yes. Vidas: Not too deep on the bench. Ausra: That’s right, yes. Vidas: Basically, lean forward. Ausra: Yes. A little bit, yes. Vidas: Does it take practice to figure out a comfortable position? Ausra: Of course. It takes a lot of practice. Vidas: So, I guess people who will be struggling with this need to remember that it’s not an overnight success; because you have to play around, and figure out your comfortable position on the organ bench while playing technical exercises like scales or arpeggios with pedals. Ausra: And also the bench height might not be correct for your case, so you need to adjust that, as well. And--have you noticed that some organists place the organ bench a little bit... Vidas: Diagonally? Ausra: Diagonally, yes. Vidas: To the left. Ausra: What do you think about that position? Vidas: The left side is farther from the keyboards than the right side, right? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: You sort of face a little bit...strangely. The idea behind this approach is that you put your right foot on the swell pedal a lot-- Ausra: Yes. Vidas: To manipulate the box. And for this technique to work, you need to pedal your pieces extensively with the left foot. I don’t think it’s an ideal position; I think we use both feet equally often. Ausra: That’s right, yes. Vidas: Especially if one piece in your repertoire is like, from the 18th century, from the Baroque period, without any swell pedal, and then you suddenly change to Franck or Widor, where you need the swell pedal. Do you think you will have time to change the position of the bench? Ausra: Probably not. But I know that some organists sit like this all the time. They come to be so used to this diagonal position of the organ bench that they cannot play straight. It sort of amazes me. Vidas: And they’re very particular about this. Ausra: I know! Vidas: They mark the distance on the floor with a special marker! Ausra: Yes. So, but you need to see for yourself what works for you. Vidas: And sometimes it doesn’t work. Sometimes you encounter an uncomfortable bench, or uncomfortable pedalboard. So, that’s ok, too. You have to know that it’s temporary, because you will not play (probably) on that organ for your entire life, right? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: You will switch to other instruments. And you will get used to this a little bit, and adjust. Ausra: That’s right. Vidas: Alright, Ausra--what would be your last, final advice for people about playing pedals without hands? Ausra: Well, just try to do it, and... Vidas: Don’t give up. Ausra: Yes, don’t give up! Eventually you will succeed. Vidas: Because...your feet also have muscle memory! Ausra: That’s right. And it’s not as hard as it seems in the beginning. Vidas: And I think you could also take a slower tempo. A lot of people say, “I’m practicing very slowly!” But when I check their tempo, they’re too fast, actually. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: Twice as fast as we would advise! Alright, thanks, guys! This was Vidas. Ausra: And Ausra. Vidas: Please send us more of your questions; we love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice… Ausra: Miracles happen. John Higgins asks a question about playing arpeggios in the piece:

If you are in a situation like John, I recommend to practice playing the chords consisting out of these notes. Play them together, without starting on the lowest or the highest note. Aim for at least 3 correct repetitions in a row and do it extremely slowly. Another technique which helps is transposition of these arpeggios. But don't start transposing to other keys right away. Instead, try to analyse the arpeggios mentally and understand what kind of chords they comprise. For example, in the above case, E-C-G-E-C-G-E-C is a C major root position chord and D-B-G-D-B-G-D-B is G major 1st inversion chord. Even better, you can identify each note not only as belonging to a particular chord but being a certain scale degree in this key (G major). For example, these two arpeggios would consist of 6-4-1-6-4-1-6-4 and 5-3-1-5-3-1-5-3. Naturally these chords are the subdominant chord (C major) and tonic 6th chord (G major). Since scale degrees really help "to translate" the music you are playing, I am pretty sure that playing them without looking at the fingers will become for you much easier as well. Ausra's Harmony Exercise: Here's what Andreas, one of my subscribers wrote to me yesterday:

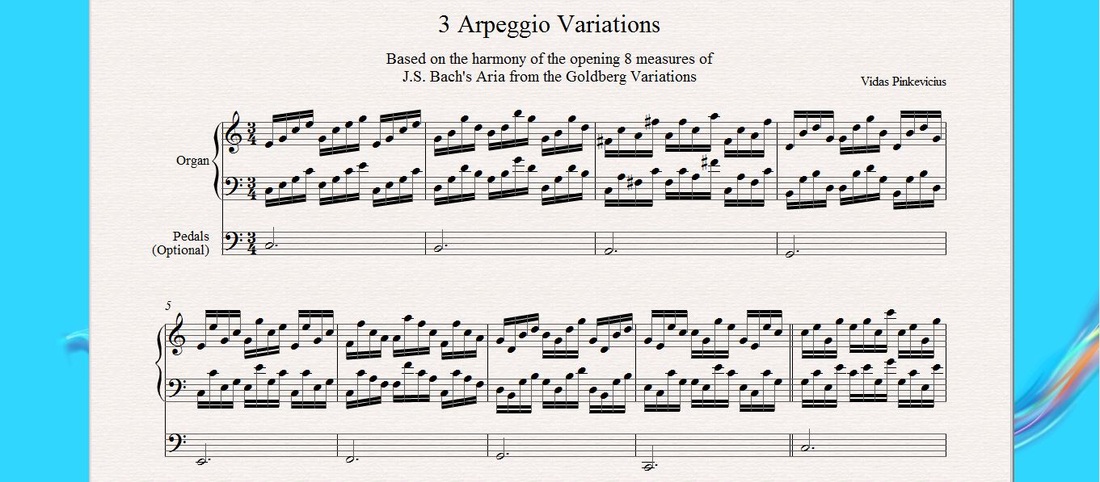

"Would you know a piece of literature about what I'd call the theory of arpeggios? Or more arpeggio sheet music for practice? I'd like to compose my own organ music, and I'm desperately in love with arpeggios (Bach, but also later composers), and I'd also like to dig a bit deeper into what I think is the theory behind it. Arpeggios are based on certain harmonic patterns, but a nice arpeggio is more than just a chord split up into separate notes. Any theoretical text or music score greatly appreciated (and doesn't have to be for organ ... there is a lot of arpeggios music for piano, and others)." After reading this request, I thought about how arpeggios can be constructed and it turns out that in any 4 note chord, there are 24 different permutations in the order of pitches: 1. 1234 2. 1243 3. 1324 4. 1342 5. 1423 6. 1432 7. 2134 8. 2143 9. 2314 10. 2341 11. 2413 12. 2431 13. 3124 14. 3142 15. 3214 16. 3241 17. 3412 18. 3421 19. 4123 20. 4132 21. 4213 22. 4231 23. 4312 24. 4321 Once you know this, you can do all kinds of interesting things with this information: you can create an entire variation based on one specific permutation only, you can mix them together in any order, you can play them in different major and minor keys, you can assign different meters and rhythmical figures to them etc. If you want to find out the limits of your arpeggio playing skills, play these 3 Arpeggio Variations with optional pedal part I wrote yesterday. They are based on the harmony of the opening 8 measures of the famous Aria by J.S. Bach from his Goldberg Variations. There are total of 24 measures in this piece (actually 25, if you count the final chord) and each measure features one specific permutation of the four-note chord in the above order. Don't feel compelled to practice them in a fast tempo as there are certain stretches for the hand that need to be played carefully and slowly at least at first. I hope you will find these variations useful. |

DON'T MISS A THING! FREE UPDATES BY EMAIL.Thank you!You have successfully joined our subscriber list.  Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas

Authors

Drs. Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene Organists of Vilnius University , creators of Secrets of Organ Playing. Our Hauptwerk Setup:

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

This site participates in the Amazon, Thomann and other affiliate programs, the proceeds of which keep it free for anyone to read.

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed