|

David from USA writes that his dream for organ playing is to be able to play in such a manner and with such excellence that it rouses a congregation, gives them a meaningful, beautiful worship service, and brings all the participants closer to God in the beauty of music. The three things holding him back are: self-confidence, level of achievement on a technical scale, and the ability to improvise on hymns for service singing.

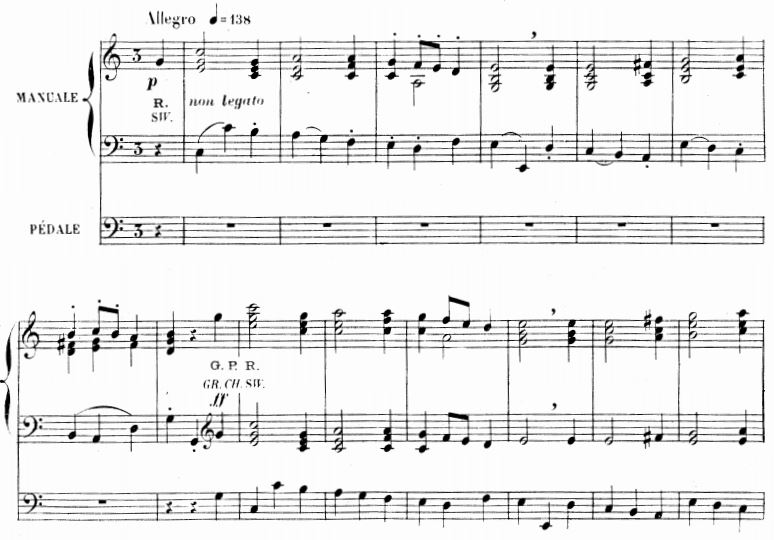

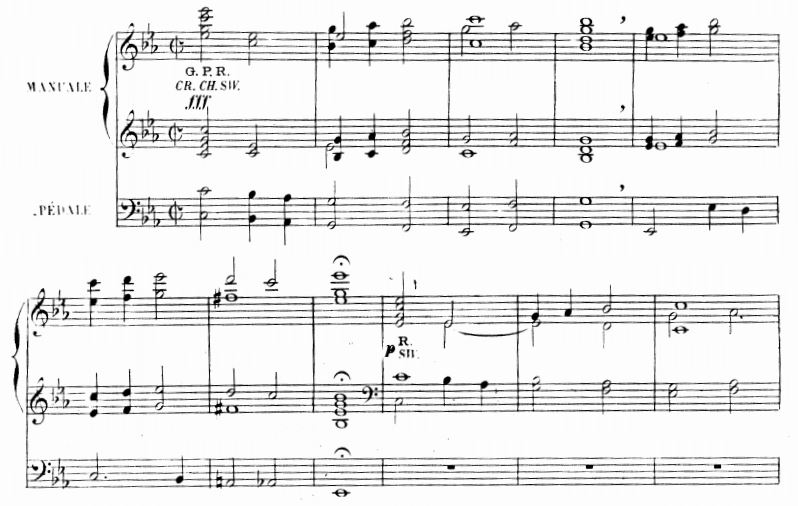

So David and many of my other readers have felt this voice calling unto them to rise to their potential, to enrich the lives of other people with the enchantment of organ and liturgical music and to inspire them to become better human beings. Is it always easy to say yes to this voice? Or can you sometimes turn the blind eye to your true mission in life and go on with your daily routine? I would guess that more often than not we do try to ignore our calling. Because it’s scary, because it might not work, because we feel that it’s not our turn, because we haven’t been picked by the people with authority. Just like David, we lack this self-confidence, that in the end it’s all going to be OK. Just like him the technical challenges (especially when you get older) seems so time and energy-consuming that we don’t want to take up this burden upon ourselves. When your mission is to create beautiful music for church services and you’ve been told about the difficulties in learning to improvise on hymn tunes, naturally we try to convince ourselves that only people with great talent can achieve this. We might even persuade ourselves that our life as it is now is just too dear to us, that we don’t really want this change because deep down we feel what kind of sacrifices our mission will require from us. If it’s not so easy to make ourselves believe that our life doesn’t require change, we might forcefully endeavor to proof this to ourselves. This might take the shape of sticking to our current habits of ineffective practice, of jumping from one piece to another without actually learning anything (I’m not talking here about the sight-reading practice with intent), of improvising without actually having anything important to say, or simply, quitting. All of this we do with only one intent: To convince ourselves that climbing out of this bucket full of other crabs is not for us (and yes, other crabs do want us to stay inside this bucket with them because they are fighting their own resistance). I think we can do better than that, can't we? Sight-reading: Kyrie II (p. 2) from the Mass for the Parishes by François Couperin (1668-1733), one of the most influential French Classical composers and organists. Hymn playing: Let Children Hear The Mighty Deeds

Comments

Pavel has a goal of playing organ professionally and he always dreamed of playing this instrument. But for him the greatest challenges are finding time for practice, developing hand and feet coordination, and finding a good organ method.

When you have such a dream like Pavel’s, you know that you have been called. You go about your normal life and your everyday business but somehow you hear this voice inside you gently telling that you should do it. The love for the organ can arise gradually day by day when you can’t actually remember how it all started but it also be like a sudden revelation. It can happen after a concert and a meeting a great organist or perhaps after “incidental” visit to an interesting organ itself when you can see, hear, and touch this old instrument, even smell it. And the love for this organ, even despite its poor state, horrid tuning, and misshaped pipes will follow you wherever you go. If you’ve heard this call, you have only two choices – to accept it and to venture to the previously unknown and risky world dreaming to learn to play it (but in reality never knowing what will come out of this dream) or to ignore it, to go on with your normal life. For some of us, there’s another call here, too. Even if you always loved your organ and played it for a long time, maybe today, maybe right this minute as you’re reading these very lines you can hear this gentle voice deep inside you. It’s such a quiet voice, barely audible (and you’ve ignored it many times before). Maybe it’s not even a voice, it’s more of a feeling. It invites you to become a pro, in your mind, at least. Especially in your mind. Will you answer this call? Sight-reading: Part II: Adagio (p. 7) from Organ Sonata No. 1, in F minor, Op. 65 by Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) who was a German composer, pianist, organist, and conductor of the early Romantic Period. Hymn playing: Jesus Christ, Our Blessed Savior In response to my article about the invertible counterpoint, John wants to know why are parallel octaves and fifths forbidden? What rule forbids them?

This is a very important question to understand. We usually don't see two consecutive unisons, fifths, or octaves followed by one another (with some exceptions) in classical tonal music (not so in pop music and jazz - parallel fifths are quite common). To answer this, we have to look deeper into the theory of the art of counterpoint in the Renaissance. Specifically, let's see what Gioseffo Zarlino, the great 16th century Italian music theorist and composer had to say about it in his 1558 treatise the Art of Counterpoint: "They [ancient composers] realized that harmony results from things that are diverse, discordant, and contrary to each other rather than alike in every way. If harmony is born from this variety, it follows that in music not only must the parts be distant from one another with respect to pitch, but their movements should be different, and they should contain diverse consonances of various ratios. The more harmonious a composition seems to us, the more variety we will discover in it: in the vertical distances between its parts, in its movements, and its proportions." So what Zarlino is really saying is that parallel intervals inhibit the independence of voices. By the way, parallel fifths were perfectly acceptable in the late Middle Ages - the age of organum by such composers of the School of Notre Dame as Leonin and Perotin (12th-13th centuries). Around that time organs were tuned in pure perfect fifths (the Pythagorean temperament) and the thirds sounded out of tune and were avoided. If you want to imagine this style, just take any tune of Gregorian chant and supply the second voice in parallel fifths above the melody and you will start to hear some old and archaic sounds - something similar to the 12th-13th century music (though it was more complex than simple parallel fifths at that time). What about the parallel thirds in the art of counterpoint? Well, even the thirds cannot be both major (F-A, G-B) because the ear perceives the dissonant augmented fourth F-B between the outer voices in these two intervals very clearly. The thirds were best used as major and minor in alternation. Sight-reading: Ach Gott vom Himmel sieh darein by Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck (1562-1621), the Great Orpheus of Amsterdam, also called Maker of German Organists (Deutsche Organistenmacher). Hymn playing: Jesus Christ, Our Blessed Savior Sam writes that his goal is to become a church organist, and perform all organist functions from accompanying the congregation and choirs, to playing the liturgy (Lutheran and Catholic), and also be able to improvise.

The three things that are stopping him from doing this are lack of strong foundation, repertoire that will make him progress, and good practice techniques. Sam is right about the importance of having a strong foundation to your success in organ playing. But actually overcoming his other challenges (finding graded repertoire and applying good practice techniques) will most likely build his foundation for him. So what you need to do, if you face similar obstacles to Sam's is always remember how you can find a suitable repertoire. This is done by the following way: A good repertoire should be a quality music and it should make you stretch (but not too much). It shouldn't be a piece which you can sight-read without any difficulty. On the other hand, you should pick a piece which you can imagine performing in the next few months (not years). So what are the basic guidelines in determining whether or not your piece is suitable for you to learn? It's actually very simple: If you can sight-read separate voices of this piece at a tempo which is 50 % slower than a concert speed with 5 mistakes per page or less, then you can do it. Anything less than that will be a long shot for now. Sight-reading: Menuet-gothique (p. 4) from Suite Gothique, op. 25 by Leon Boellmann, French Romantic composer and organist. Hymn playing: He Was Not Willing Margaret writes that her dream for playing organ is to play faster and without mistakes. For her the main obstacles which prevent her reaching this dream are the difficulty in reaching a faster tempo, eliminating mistakes and memorization of the score.

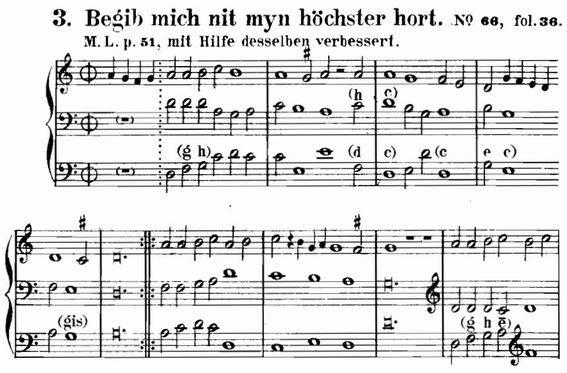

The dream that Margaret has is common to many organists. But it's not so easy to make it a reality. So often people can only play rather slow music and when they try to play faster, lots of mistakes appear. This is frustrating. If you experience such challenges as Margaret, you have to understand that it's better to play slower than with many mistakes. Therefore, choose the tempo according to your level of ability. By repeatedly practicing very slowly and reducing the texture to single voice and various voice combinations, you will be able to eliminate mistakes and reach the level when you can play rather slowly but fluently. If you want to play faster, perhaps you need a) to work on your technique and b) to practice your pieces at the concert tempo but stopping and waiting at the smallest fragment imaginable - a quarter note. Once you can play this way until the end of the piece at least 3 times without mistakes, stop every two beats, then one measure, two measures and so on always expanding your fragments and playing the music inside the fragment at the concert tempo but stopping, waiting and preparing for the next fragment. If you want to memorize music easier, you have to develop a systematic procedure of practicing short fragments 5 times while looking at the score and 5 times from memory. Usually the longest fragment you can remember this way is one measure. As you might have already guessed, after memorizing one measure fragments, start expanding them little by little from memory. If you haven't done so, try to learn something about keys, chords, chord progressions, cadences, and modulations. This will help you understand how your piece is put together and consequently facilitate the process of memorization. Sight-reading: 3. Begib mich nit myn höchster hort (p. 26) from Buxheimer Orgelbuch (ca. 1450), a German Renaissance collection of organ music. Hymn playing: Hark, the Voice of Jesus Calling In the learned Renaissance and Baroque music circles, it was common to study counterpoint. Theorists, composers, organists, and other musicians got together and immersed themselves in various metaphysical speculations. This all comes down from the fact that music was part of the classical education students received from universities.

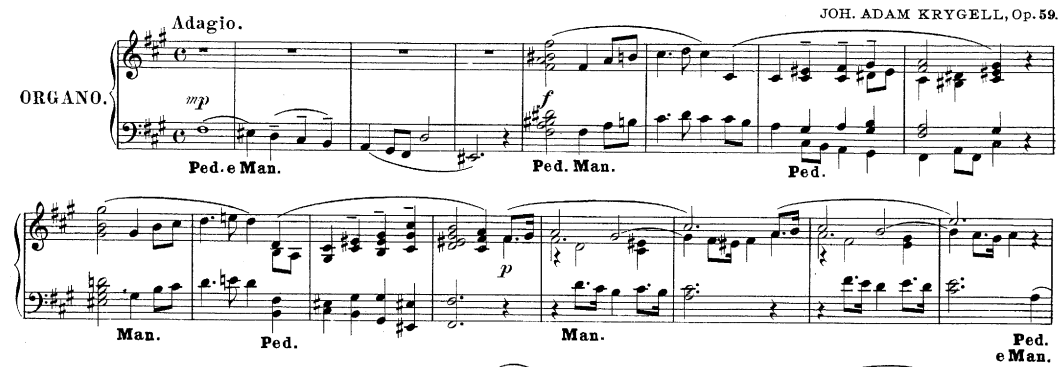

This system included the education in 7 liberal arts (just like in the Ancient Greece): the Trivium (grammar, dialectics, and rhetoric) and the Quadrivium (arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music). To make it easier to understand, you can imagine that as part of the Trivium, students learned everything about the words and as part of the Quadrivium they learned all about the numbers. The most fascinating fact (and the most different from today's perspective) is that the study of music was concerned with numbers and not with emotions. This all makes sense when you think that all music consists of intervals and various proportions. Just as architecture was concerned with the numbers embedded in space, music basically was concerned with sounding numbers. The study of Trivium and Quadrivium was in preparation of the philosophy and theology, of course. So students of such old polyphonic masters as Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck and Gioseffo Zarlino liked to study counterpoint together. For example, Sweelinck's students Matthias Weckmann and Johann Adam Reincken wrote down everything the old master (who was called the Great Orpheus of Amsterdam and Maker of German Organists) taught them about the art of counterpoint. The result is Sweelinck's Composition's Regeln (the Rules of Composition - vol. 10 of the "Werken") - an indispensable source of inspiration for anybody interested in the style of composition and improvisation of the 16th-17th centuries. We have to remember that in those days the art of contrapuntal composition was a science in itself with many seemingly mysterious rules and techniques. Invertible counterpoint is one of those techniques. You know that if we invert an interval of the third, we get a sixth and vice versa. This is done by exchanging two voices by the octave. This is called invertible counterpoint at the octave. It's simple to understand. Here is a list of intervals and their inversions: 1 - 2 - 3 - 4 - 5 - 6 - 7 - 8 8 - 7 - 6 - 5 - 4 - 3 - 2 - 1 So you see that if we invert a fourth (C-F), we get a fifth (F-C) and vice versa or instead of a second (C-D), we get a seventh (D-C). That's why thirds (C-E) and sixths (E-C) are so valuable here. They are the sweetest intervals. But Reincken, the creator of the longest chorale fantasia in the North German organ school on record ("An Wasserflussen Babylon" - 327 measures), uses even more advanced counterpoints - invertible counterpoint at the tenth and the twelfth. Here's how the intervals are inverted in these cases: Invertible counterpoint at the tenth: 1 - 2 - 3 - 4 - 5 - 6 - 7 - 8 - 9 - 10 10-9 - 8 - 7 - 6 - 5 - 4 - 3 - 2 - 1 Here you can't play two consecutive thirds or sixths because in inversion you will get forbidden parallel octaves or fifths. Invertible counterpoint at the twelfth: 1 - 2 - 3 - 4 - 5 - 6 - 7 - 8 - 9 - 10-11-12 12-11-10-9 - 8 - 7 - 6 - 5 - 4 - 3 - 2 - 1 In this counterpoint, thirds are very useful because you get tenths in inversion. But sixths are used very carefully because the inversion would create dissonant sevenths. Remember that you, like those students of Sweelinck can experiment with invertible counterpoint by writing short melodies and supplying them with counter-melodies with desired intervals. Always play everything you write down to really discover what works and what doesn't. Sight-reading: Marcia funèbre, Op.59 by Johan Adam Krygell (1835-1915) who was a Danish organist and composer of the Romantic period. Hymn playing: God, That Madest Earth and Heaven Matthias writes that he's coming from the "Schnitger-Land" near Hamburg, Germany and his dream is to play Johann Adam Reincken's "An Wasserflüssen Babylon" in St. Katharinen, Hamburg which was Rencken's church at the time. For him it is very hard to find out the musical themes and cantus firmus (chorale melodies) in this many-sided masterpiece. In order to play such an awesome masterpiece, he wants to know all about the stylistic devices of the North German Baroque school and melodic lines in such organ works.

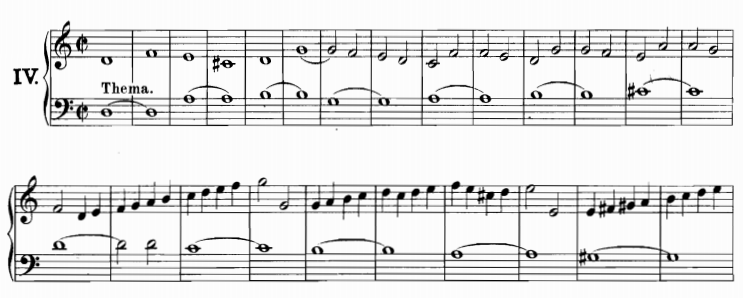

I'm sure it's not easy for Matthias to find out the compositional devises in North German chorale fantasias. They may be extremely elaborate in these multi-faced works. To make this task easier for him and for any of my subscribers who are interested in such intricate music, you can do the following things. Get familiar with the chorale tune of the chorale fantasia. This might mean searching for the harmonized version of the chorale or a simple one voice melody. Note how many phrases this chorale tune has, what kind of key or mode, what kind of cadences you see at the end of each phrase. Know that each phrase of the typical chorale fantasia of Buxtehude, Reincken, Weckman, Tunder, Bruhns, Scheidemann, and other North German composers might have any or all of the following techniques: 1. Ornamented chorale in the soprano or the tenor in 3 or 4 voices 2. Cantus firmus chorale in any of the parts in 2, 3, or 4 voices 3. Combination of cantus firmus and ornamentation techniques in 4 voices (the bass or the tenor has long chorale notes but the soprano or the tenor has unrelated ornamented melody (counterpoint). 4. Chorale ricercare with imitative counterpoint (fugal chorale) 5. Melodic echos over the cantus firmus in augmentation in the bass 6. Chordal echos for manuals only 7. Echo passages in two parts in sixteenth-notes The composer might treat each of the above techniques at the tonic, dominant or subdominant level making it a fairly lengthy piece. In the chorale fantasias of more conservative composers the themes or chorale melodies and their fragments are always clearly visible in the score. But with Reincken it's different. He might start out with the cantus firmus melody in long notes but later develop the same chorale phrase into something more advanced when you don't easily see the notes of the chorale anymore. Most of them are there, though but you have to look deeper. Sometimes you will discover the chorale notes hidden in the diminutions of the chorale where they can be found on the main beats of the measure. But often it's even more complex and creative than that. Some notes are skipped, some played at different octaves, and some fall not on the beats but somewhere in between. And of course Reincken doesn't hesitate to use the entire range of the keyboard for his ornamentations. That's what makes his masterpiece so unique and remarkable. Sight-reading: Duo IV "Ave maris stella" (in Versets of 2, 3 and 4 voices, Fabordones, Intermedios, p. 4) by Antonio de Cabezón (1510-1566), a blind Spanish Renaissance composer and organist. Hymn playing: Faith of Our Fathers John writes that his dream in organ playing is to advance sufficiently to be able to perform well J.S. Bach's Passacaglia and Fugue in C minor, BWV 582, and to develop his improvisation skills in the Baroque style. However, obstacles such as maximizing the efficiency of the practice time, finding an organ that's available to practice on, and the difficulty in improvising polyphonic music stops him from reaching his full potential.

What a wonderful dream John has! It's not an ordinary simple dream. A person who wants to learn to improvise in the ancient styles clearly has a vision of becoming a complete musician. Obviously this involves not only creating your own music on the instrument but also in writing, too (much like Bach and other old masters did). I'm sure quite a few of my subscribers would love to be able to improvise like Bach, Buxtehude, Pachelbel, Bohm, Scheidt, Sweelinck and others. And that's the problem. I can feel your pain when you try to improvise polyphonic and contrapuntal music and fail. Perhaps you try to improvise chorale variations with imitations, or an ornamented chorale with fugal entrances before the chorale tune enters in the soprano. Or maybe you try your hand at creating 3 or 4 part fugues (with answer, countersubject, episodes, subject entries in other keys, and even strettos at the end). You stop and try again and again. You know what you want to do, but your technical, practical, or theoretical limitations won't let you do it. It's very frustrating to take a hymn tune or a polyphonic subject, figure out a key, a meter, tonal plan, form, and attempt to improvise only to discover that your mind is not moving fast enough. Your fingers might be able to play what you want but you can't seem to give the orders to them fast enough. The result of this is stumbling, irregular pulse, stalling musical ideas, and general feeling of disappointment. If your failures and frustrations continue and you can't feel any progress, you might even think that you are not creative enough, that you are not disciplined enough, and that this is not for you although deep inside you always felt for many years the fascination with and the desire to learn the ancient and mysterious craft of polyphonic improvisation. The first step is to start looking at the music of old Baroque masters with new eyes. What I mean by that is that the majority of written down pieces that survived the passage of time was created and published or copied with the intent that they would serve as models for composition and improvisation of the students of the composer and perhaps even for the future generations of organists as well. So what you do in order to start learning the craft of improvisation in the polyphonic Baroque style is to take a piece of music that you love, that you want to imitate and begin to take it apart. Try to understand it's form, tonal plan, imitative techniques etc. In other words, try to look at it as the old master who created it three or more hundred years ago. Then take a pencil and a sheet of music paper and begin to compose a similar piece or an exercise of your own based on its techniques. You can use different themes, different chorale or hymn tunes but try to keep the same form, tonal plan, the same order of thematic entrances, ornamentation procedure, and similar rhythms and intervals in the counterpoint. The key here is writing what you want to play. That's how old master's did. They also took apart their models and wrote down similar compositions and exercises of their own. Don't stop with just one or a few pieces you create on the same model. It's best if you insist upon just one model for a while and create tenths and even hundreds of its imitations. Then you start to feel that this technique becomes your own and you can use it in any key and in any situation. Basically, you will become a master of this technique. At first you will write very slowly and make many mistakes but later the process will be faster and faster. At the end you will almost write as fast as you think of those ideas, without any hesitations. I know that all of this might sound overwhelming and it is. Baroque style is vast and implies many different genres and techniques that masters used in the old times. For starters become a master of just one or a few techniques. Persist until you achieve certain fluency with them. Assimilate them to the degree that you can write them in any key you want, major or minor. At the same time you will start to feel the urge to apply them in playing spontaneously on the instrument. And this will no longer feel like the old intimidating task because by now you will have fully mastered it and your brain will function fast enough to give the orders to your fingers before they depress the keys. Most of all, feel that the result is not the goal. Process is the goal. It will keep you motivated to stay focused. Sight-reading: Part I: Allegro moderato e serioso from Organ Sonata No. 1, in F minor, Op. 65 by Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) who was a German composer, pianist, organist, and conductor of the early Romantic Period. Hymn playing: By Grace I’m Saved Ann writes that her dream in organ playing is to be able to play and use different registrations because she tends to use the same ones all the time. However, it's difficult for her to find time to practice, have the courage to try new things, and to know what stop combinations to use.

Knowing your instrument and the intricacies of organ registration is something every organist should strive for. So very good - Ann has a great goal. The registration is a broad topic and it's best to subdivide it to various organ music genres, various historical periods, and various national schools of organ composition. Learn them one by one. It's sometimes science and sometimes art. It's best if you could try many different organs. The person who has the most experience with the widest amount of instruments, music, styles, and national schools, wins. Listening and comparing various recordings and videos of the same piece helps a lot, too. The first step is of course to try something new every day. That's why I send these varied sight-reading pieces every day for you to practice. Often there you can find also specific registration directions for a specific situation. Sight-reading: Elevazione per Organo by Floriano Arresti (1667-1717), an Italian organist and composer of the Baroque period. The registration for the Italian piece for Elevation section of the mass is usually a Principale and Voce Umana - a soft and singing 8' principal together with the undulating stop Voce Umana or Unda Maris (in the descant range) which are tuned slightly sharper and give the effect of the natural tremulant. Hymn Playing: All Praise To Thee, My God, This Night Russ writes that his goal is to give and receive pleasure from organ music and

introduce people to the magnificence of the organ. However, lack of self confidence, patience, and correct technique are holding him back. I believe every organist should have a goal like Russ does. This is really excellent! It's graceful, elegant, and simple. If you want to gain self confidence, you first have to know your instrument, your music, and yourself. Knowing your instrument involves all the intricacies of combing various stops and stop combinations and knowing when to change the registration. Knowing your music is of course being able to play it by heart (from memory). In order to do it, you first have to master the piece from the score by repeatedly and extremely slowly playing various voices and voice combinations and the entire texture in small manageable fragments of about 4 measures of duration. A side effect of doing this is that you will gain patience and also develop correct technique. So in reality it all comes down to slow, regular, and persistent practice. By doing this you will also come to understand yourself, your strengths and your weaknesses. It's all very simple - when you practice, you move forward. When you give up, despair, doubt yourself, seek shortcuts, silver bullets, and shiny objects - then you are sabotaging your own efforts and success (until your next readjustment of focus). Although it's a long road head, the pleasure comes from knowing that you are inevitably moving closer to your goal every day one step at a time. What's your next step? Sight-reading: Introduction-Chorale (p. 2) from Suite Gothique, op. 25 by Leon Boellmann, French Romantic composer and organist. |

DON'T MISS A THING! FREE UPDATES BY EMAIL.Thank you!You have successfully joined our subscriber list.  Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas

Authors

Drs. Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene Organists of Vilnius University , creators of Secrets of Organ Playing. Our Hauptwerk Setup:

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

This site participates in the Amazon, Thomann and other affiliate programs, the proceeds of which keep it free for anyone to read.

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed