|

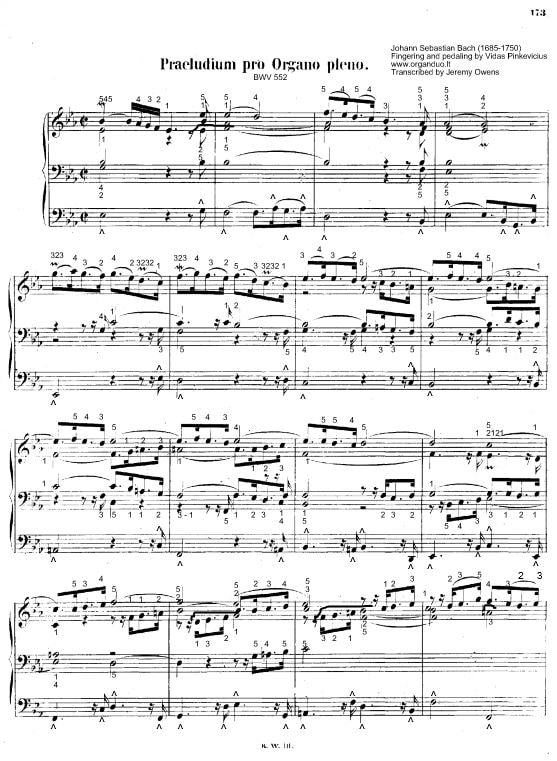

Would you like to master Prelude and Fugue in Eb Major, BWV 552 by J.S. Bach?

I have created this score with the hope that it will help my students who love early music to recreate articulate legato style automatically, almost without thinking. Thanks to Jeremy Owens for his meticulous transcription of fingering and pedaling from the slow motion videos. Advanced level. PDF score. 18 pages. 50% discount is valid until March 7. Check it out here This score is free for Total Organist students.

Comments

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 167, of #AskVidasAndAusra Podcast. This question was sent by David. And he writes: Today I had to play "O Worship the King" for service. I wanted to make it a little more exciting, so instead of playing just the last part of the hymn as an introduction, I improvised a short modulating fanfare with Trompette En Chamade on the Swell, then on the Great with a rather full sounding registration continued with the the second half of the hymn only slightly re-harmonized followed by a one beat rest to let the congregation know it's time to join in. It was very well received, and it was fun to play, but I wonder if you have any suggestions for beginner/intermediate organists for both hymn introductions and alternative harmonizations. I think some time ago either you or Ausra indicated that one has to be careful with alternative harmonizations and that are not a good idea on the last stanza as a general rule, but in our congregation they seem to work well and add interest, and the people seem to sing all the more enthusiastically. Perhaps you have a suggestion or a formula for improvising Hymn introductions or could recommend a publication with somewhat simple introductions. Anything you can suggest would be wonderful. Thank you! V: Ausra, this is a question that is probably bothering a lot of church organists. A: Sure, because you know it is a big part of your job. V: To introduce the hymn. What’s the most common introduction? Probably to play the entire stanza in four parts for congregation. A: Well or just the last eight with sometimes even four measures. V: The last phrase or two. A: Yes. V: Mmm, hmm. Or the first phrase and the last phrase. A: That’s true. V: Is this a boring way to introduce a hymn? A: Well, not necessarily. It’s sort of a traditional way. V: Do you think that David should do this or, anything else you could add? A: Well, you can do it for some hymns and then for other hymns you may, you know, play an elaborate introduction. V: If you were invited to play in David’s church what would you do? A: Well, now when I know that his church, his congregation loves elaborated preludes, maybe I would play some fancy introduction too. V: Would you play with ornamented chorale in the right hand, version? A: Yes, could be. V: Or in the left hand, tenor line. A: Maybe I would do it in the right hand. It would be easier. V: What about in the pedals with augmentation? With Posaune. A: Well, yes but I wouldn’t play introductions with Posaune, I think it would be too crushing, too loud, probably. What would you do? V: I think any example that we can find from Bach’s Orgelbuchlein would work well here, except, except in those days, the hymns were played rather slowly, and if you notice the texture of their chorale prelude and the rhythm of that tune is basically twice as slow, which means probably that the entire piece would last a minute or two, here. And that’s usually in modern terms, too long. A: Yes, for example, I myself don’t like long introductions to the hymns. I mean it’s okay to play, you know, to do fancy postludes for example, but if you do long introductions for each hymn, I believe the service might become longer and longer. V: So if you take for example the first phrase and the last phrase, but treat it as a chorale prelude based on the model from Orgelbuchlein, would that be sophisticated and creative enough? A: I think so yes. V: And not too long. A: Yes. Plus you know, in America there are so many publishers that publish church music, and you can find actual introductions to various hymns. Although you have to check and to be careful that you play your introduction and your hymn in the same key. Because there might be different keys in those. V: And then they have alternative harmonizations for the last stanza usually. A: Sure. Yes. V: Would you play the last stanza somewhat different then? A: Well, it again depends on the hymn itself. Because not for each hymn is the proper way to do it. Especially, for example, if you are playing in a Catholic Church and you playing, let’s say during Lent, I wouldn’t do it. But if it’s Easter on Sunday, then yes, okay. Why not? V: Mmm, hmm. And you can even transpose your harmonization, up a step or an entire step, entire whole tone higher. A: Would it like in pop music, yes? (Laughs) V: Exactly. A: Yes. It would give your more excitement. V: Would you then choose to play modulating interludes between those two stanzas? A: No. I wouldn’t do that. V: Why? A: I’m afraid I might be kicked out of the church, as Bach was. V: What’s wrong with that? Look at Bach, (laughs) what he achieved later? A: Well, but at that time, he lost his job. V: That’s okay. He found another. And you know, if you did that consistently, their basically voice about you would, you know, spread around the mountains, across the globe, that you are one and only. A: Yes. I think, you know, sometimes it’s a problem that organists wants to demonstrate his or her ability, above everything else. But you know, while playing in church and especially doing hymns, because we always have texts, and I think the texts in hymns are the most important part. So, and I mean that your accompaniment should never, you know, sort of cover the text. That’s my opinion. V: Yes. You should probably choose the texture and the registration based on the text. A: Yes, I know, and you can register the hymn accordingly. V: That’s obviously for another topic of discussion; registrations, right? It’s not things that David is asking, but, yeah, he could probably use some alternative harmonizations and make introductions, and sometimes even modulating fanfares, right? It’s nothing against the rules, right, if it’s a solemn occasion. If it’s a festivity like Christmas or Easter or Pentecost. I think one of the easier ways to introduce a hymn is to start with a single voice, let’s say soprano. Then after the first phrase, you add the altos, so then two part texture. After the second phrase you add the tenors, then the three part texture. And for the last phrase, all four parts come in. A: That’s a nice way to introduce a hymn. V: Gradually making it more sophisticated, more thicker texture and a little bit louder, right? That’s if the hymn has four phrases. A: Yes. V: What about if the hymn has six phrases, Ausra? You should add the six voices then? A: (Laughs). No. V: Why not? A: (Laughs). Would you like to do that? V: Yes! Double tenor. I love it. A: Well it would be very hard. Go ahead and do it. V: I did actually. It didn’t work. So I stopped doing it. A: So I would rather stick with four voices on hymns. V: Or even two voices. What’s wrong with two voice introductions? You could have a Bicinium, right, for entire stanza. Or even the first phrase and the last phrase, very thin texture, soprano and the bass playing basically outer voice, outer voices of the hymn. Maybe a little bit with embellishment in the right hand or the left hand or in alternation. Would that work? A: I think it would work just fine. And because you have to play in church each Sunday and do a few hymns, so, well you can use all these methods and see what is working for you. V: And don’t forget the three textures where you play three parts and you can place your hymn tune in any of the parts, soprano, tenor or the bass. A: That’s right. V: Excellent. So guys, we hope this was useful to you. Please send us more of the questions. We love helping you grow. This was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: And remember, when you practice… A: Miracles happen! AVA166: How To Handle Large Quantity Of Music For Prelude, Postlude, And Offertory Every Week?2/26/2018 Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 166 of #AskVidasAndAusra Podcast. This question was sent by David and he writes: Dear Vidas and Ausra, At the churches where I play, the organists have to play 2 or 3 hymns every Sunday, plus a prelude, postlude, offertory, and Doxology (old 100th), and sometimes accompany a choir anthem as well. That is between 6 and 8 pieces every week. Do you have any suggestions how to handle that quantity of music? Especially the Prelude, Postlude, and Offertory... Thank you! V: That’s a lot of music every Sunday. A: Yes, but that’s life of the parish organist. That’s what we did when we worked at church. V: Do you remember the time when you first started playing in church in Vilnius. A: Yes, I remember it was the second year of my organ study at the Academy of Music I had to work at church. V: Did you have to play the hymns only or also some organ music. A: Well, I had to play both. Plus because it was a Catholic Church we had lots of other stuff going on playing such things like litanies for example, and Psalms and so on and so forth. V: And the masses were not only on Sundays but every day. A: Yes, every day and we had that you know Adoration hour of the sacrament. So also every day. And this was sort of a little bit of nonsense because we would have to play two hymns at the beginning of it and two at the end of it. And it lasted for like an hour and the church was unheated and it was horrible, horrible you know to spend those fifty minutes in that cold church between two hymns and two hymns. V: And doing nothing. A: Yes, I know it’s impossible to play when it is so cold at least for me. V: Is it, you know sometimes if you pray very hard you can heat up the area around you. A: Well, I can’t maybe you can. V: I tried and nothing happened. A: I know. But in terms of my starting playing in church, of course at that time pedalling was still challenging. But for me the biggest challenge was to follow that liturgy. Because in Catholic Churches we have those invocations and each priest sings a little bit different, and in different key and you have to catch up. And some priests are so badly musically educated that they cannot keep the tune and they modulate like a few times and you never know on which key you will end up so all this gave me such a big stress. V: How did you handle the stress then? A: Well little by little I learned everything. V: Uh-huh. Like we have a saying, like a dog which is being led to be hanged too frequently. This dog basically get used to that. A: I don’t think it makes sense in English. V: Probably not. They have a better expression. A: I’m sure of it. There are so many idioms in English. So, let’s go back then to the question. Well you know I received such a good school in the Catholic Church that later on while playing in the Christian Scientist Church in the States and also the Lutheran Church in the States it seemed so easy and so nice. But in terms of selecting the right repertoire I think this is very important for David and for other church organists. At least if you don’t have very good technique, well advanced technique, it’s better to choose easier pieces for prelude, postlude, offering. And if you are new in church so each Sunday it seems like new hymns are sung and you have to learn how to play the new hymns but after a while we, you know repeat themselves. V: So after one, two or three years. A: Yes, that’s true. And even actually sooner because some of the hymns are repeated quite often, as for example Doxology. V: Well yes, my own church playing experience started early on when my Mom and I went to the church nearby where we had this summer cottage that was where her parents lived at the time. And this was a wooden church and it had an antique 19th century organ by anonymous organ builder and my Mom asked the priest to let me play because I was studying at the music school at the time maybe it was like sixth grade I think. And I started playing excerpts of my choir repertoire from school. I sang a soprano part and little by little I sort of harmonized those excerpts without even knowing anything about the chords. And actually at that time I started to remember how my friends were fooling around during recess, or intermissions between the classes. They were sort of improvising and playing popular melodies but adding on-the-spot accompaniment with the left hand. So I started doing that myself. A: In church. V: In church. And it wasn’t so bad actually. A: Did you do that during service? V: Just for fun, for me. Yes, and then the priest heard and they didn’t have a local organist that Sunday or any other Sunday I guess. And he asked me to come and play and it was a very solemn occasion I think the golden wedding anniversary of some couple. And I foolishly agreed in sixth grade to play a wedding and the mass also. I remember that the priest let me to come and practice during the weekdays of that week preparing for this wedding and mass and I found the hymnal, handwritten scores and I tried to practice those hymns selecting the repertoire as I thought it would work and then when the time came I missed the Sanctus part. A: It’s to know when to start it because if you don’t know the Catholic Mass there is that moment when the priest does his prayers and after that he sort of has to cross his arms to put his hands together in front of him and that’s the sign for you to begin Sanctus. And sometimes from the organ loft it’s very hard to see that he is doing this so you can easily miss it. V: So he started saying the Sanctus instead of playing. Then after he said the Sanctus I started playing. A: That’s funny. You usually don’t do it twice. V: But he was actually happy with that mass considering my age probably and my inexperience. A: That’s nice. I remember when I started to work at the church in Vilnius, Holy Cross Church, it was probably my third or fourth mass that I had to play and it was actually a cardinal who had to lead the service. I was so scared, I was freaking out. I think I missed something or I played something in the wrong spot. V: What was scarier? The cardinal on that occasion or myself coming occasionally to your organ loft. A: Neither you nor the cardinal. The scariest part of that church was those elderly ladies who are so devoted to the church that we spend all day each day in the church and we sort of searching for trouble and there are all these complaints about everything that you are doing, that everything is wrong, tempo is wrong, you dress is not appropriate, or you didn’t make the sign of the cross in the right moment. V: And that ended my career in that church. A: Yes, I remember that old lady chasing you throughout the downtown Vilnius. V: So, Ausra is there a shortcut that David could take in order to facilitate his liturgical playing and make life easier for him? A: Well, yes and no. Because still you will have to overcome all obstacles and all those difficulties but in order to help yourself just select easy organ music at the beginning. Maybe less pedal stuff and then later on you will catch up and will start to play harder things. Maybe you know if you are playing, I don’t know, if you have like regular Sunday service or you have like festival like for example Easter or Christmas when you have to play more sophisticated organ music. V: But that’s only several times a year. A: Yes, but for other Sunday’s you can just pick up something easier because you know if you will play easy music well it will still sound fine. But if you will pick up pieces that are two hard for you to play and you will make lots of mistakes for example, or you keep unsteady tempo then everybody will notice it and nobody will appreciate that you are playing hard stuff. The most important thing is play right. V: And probably what you are saying is that you will not get a medal for playing advanced music. A: Yes, yes, I guess so. V: Nobody will appreciate that. A: Well, yes and no. You never know. V: I mean you could play advanced repertoire when you are ready. A: Yes. V: But for now, as Ausra says, probably it is better to focus only on manuals only pieces and occasional pedal parts, maybe long sustained pedal points, which would make your life so much easier. And sight-read as much as you can. A: Yes, this will help to improve with time. And you know when playing hymns is to keep a steady tempo especially if your congregation sings together with your playing. V: I would say three things here which helped me and maybe it will help David. Sight-read as much as you can, play harmony exercises as much as you can, and improvise as much as you can. And over time, maybe in a few months even, you will notice considerable improvement. Right? A: Of course, yes. V: If you do this every day after one year your organ playing skill will be completely changed. A: Yes, and you know you can even sight-read from a hymnal for example, from your hymnal of your church. It will help you later on you know for playing hymns. V: OK, guys. We hope this was useful to you. Please apply our tips in your practice and send us more of the questions. We love helping you grow. This was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: And remember, when you practice… A: Miracles happen. Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 165 of Ask Vidas and Ausra podcast. This question was sent in by David. “In the US, we are taught to play pedal using both feet, including toes and heels on both feet. Would I be correct in thinking that in most of Europe, most of the pedaling is done only with toes?” A: Well it does not depend on the country that you are in. Either US or Europe. It depends on what style of music you are playing. If you are talking about baroque music or you’re talking about romantic and modern music. V: In Lithuania for example, there are plenty of organists that would play early music with heels and toes. A: But it just means that they don’t have a sense of good style. V: And they haven’t tried historical instruments. Just as in the U.S. there are plenty of organists who can play early music with toes only. A: That’s true. V: Because they have that experience. A: And they have many replicas too. Wonderful instruments built by great American organ builders. V: So, we highly recommend wherever you live in the world to travel a little bit around your area and see if you could explore historical instruments because even organs build at the beginning of the 19th century a lot of times they have the baroque layout and baroque type of pedalboard and for those reasons you would not be able to play with heels successfully on those instruments. A: Yes, and for example imagine if you are studying a piece for example by J. S. Bach and your playing it on a generic instrument, of course you could use both heels and toes but think maybe someday you will get a chance to travel and to play it on a historical instrument so it would be better if you would learn it right away in the right manner and use only your toes. And, for example if you are working on a romantic piece it means that you know that if you will get a chance to play on 17th or 18th century instrument you will not play that particular piece because it will not fit for that instrument. V: Ausra, should we say the right manner or something different? A: I don’t know. V: Because when we say the right manner we imply that some people play incorrectly or the wrong manner. What is right and wrong here? Can we decide? A: You know, it’s basically how would you defer what is Ketchup and what is tomato sauce. Are they same or are they different. V: In some people’s minds they are the same. A: But we are different. V: How? A: We are different in the way we are made up. Their taste is different. Although there is one ingredient in common that’s tomatoes. But that’s about it. V: Exactly. A: And you know if you are making Italian pizza you probably wouldn’t put the Ketchup on it. V: But if you don’t know the tradition you would put the Ketchup and you would say “Oh, what a lovely pizza.” A: Well, yes but would it be stylistically correct? I don’t know. It’s up to you to decide. V: Remember the first time we tried to eat pizza. That was right after independence I believe because in Soviet times nobody made pizza in Lithuania. And, the first pizzas we ordered from public restaurants there were imitations of pizza, right? A: And they were made with Ketchup, actually. V: Maybe we could say not the correct manner or the wrong manner here but maybe let’s use the term “historically informed performance practice.” A: OK, I’m sorry. I did not want to offend anybody. V: I didn’t mean you offended. No, no. Just to clarify that we don’t know all the answers here. And nobody knows actually. But it would be better to say “historically informed performance practice” because then a person can choose whether he likes it or not. A: Well you know I’m talking from my experience because you know I studied six years in the Lithuanian Academy of Music and I was taught some things good and some things not very good. But historically I don’t think that way of playing music was correct way or right way. And then I went to study abroad, I traveled quite a lot, I tried historical instruments, I tried replicas, I know I worked with Dr. Ruiter-Feenstra, and George Ritchie and of course I took many master classes with people like Harold Vogel, Bill Porter, Hans Davidsson, and I could go on and on naming them all, Olivier Latry and you know it sort of broadened my perspective. And I’ve re-learned to play the organ. I’m trying to do everything historically right. V: Historically informed way. A: Informed way, yes. Because if you sit down at a historical instrument and you would just apply what I have learned at the Lithuanian Academy of Music I would be screwed up. I could not play anything. I could not register right. I could not play pedals right. Especially if I would sit and play the pedal clavichord. That wouldn’t work at all if I tried to use modern fingering and modern pedaling. So, since have these two sides of my life I can compare it very well. So I think the later way what I learned was the correct way. At least for me. I would never go to that alt habit. V: You know Ausra, it’s very well to say for you, easy to say right? Because it changed your mind. But what about a person who sees a video on YouTube played by let’s say Cameron Carpenter right? He’s a fantastic virtuoso organist. Right? But he doesn’t necessarily play in the historically informed manner, right? But people love how he plays, how he presents organ music and his showmanship, right? So we definitely are not criticizing him here. But, an organist who sees Cameron for example thinks this is the correct way, right? But then Vidas and Ausra tells them no, no, no, you should read about historically informed performance practice, right? And then he says look at this video. If the master Cameron Carpenter plays right how can you say it is not correct? A: Well, go to Europe and try some historical instruments. That’s what I would suggest for them to do. We will speak for themselves and then we don’t have to argue. Because no, while going to the States I wouldn’t think I will find a society of organists so historically well informed. And I was actually amazed about it because before going to the United States that’s what I thought. That you know that Americans play organ fast and loud. That was my personal opinion. V: And you changed that opinion. A: I changed that opinion, yes. Of course there are still many organists that play fast and loud but there are many others that are real scholars. That can see a difference between Tomato Sauce and Ketchup. V: And the best part of this is people who know the early style and later style which is for example, being taught in the Richard Stauffer Organ Method book. They can adapt and play romantic pieces just beautifully on the romantic or modern instruments. And the early music just beautifully on the modern instruments too but using early technique. Right? A: Yes. V: So if you know more stylistically informed performance practices you can choose from them. You don’t necessarily have to use them but you have to understand why there are and how they change the style that you like. A: And I think the true artist know to show the best qualities of the organ and not of yourself. V: Why? A: Because I think organs are standing for so many centuries already, some of the older historical instruments and though even when we will die they will still keep standing. V: On this optimistic note, we have to finish here. Please guys send us more of your questions. We love helping you grow. And Ausra and I are hoping that this was useful to you. In at least raising the questions right? Not necessarily we have all the answers but we could elevate a discussion and tell us what you think. Send us your opinion. This was Vidas… A: And Ausra. V: Remember when you practice… A: Miracles happen. Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 164, of #AskVidasAndAusra Podcast. And this question was sent by David. He writes: “I'm working on a "paper" about understanding what 18th century French classical registrations really mean when an organ of that period is not being used, since, of course, the French Revolution wiped most of them off the face of the earth. It’s easier to find unicorns!” V: So it’s a fascinating question, right, Ausra? A: It is. But I can think that it still would be harder to find the Unicorn. V: Yeah, we should ask David if he found any Unicorns. A: Yes, if you would look, let’s say at Paris, in Paris, you would search for French classical organ, you wouldn’t find them, but if look in the provinces, like tiny villages, in those you can still find French classical instruments. V: And there are of course modern day replicas being built. A: Sure. V: Great. The basis for understanding 18th century French classical organ registration, probably relies not only on the organs, but on the registration suggestions by the composers. A: Yes. And I think actually, if you have little experience, I think it’s easier to register French classical pieces of organ music comparing to let’s say, German. V: What do you mean? A: Well, because, as you talked earlier, composers indicate what they want from a piece, how they should be played and registered, and French are just very systematized. V: So, people who don’t understand the system probably don’t read French. A: Yes. I mean if you know what Plein Jeux or Grand Jeux is, then you should be able to register, you know. V: Do you think that a lot of people understand the terms Plein Jeux or Grand Jeux? Maybe we should explain a little bit. A: Yes, so Vidas, let’s tell us or remind us what the Plain Jeux or Grand Jeux and what is the difference between them. V: In general terms, Plein Jeux is the sound that reminds of the organum plenum sound. Except with some difference maybe from the German. But it has, I think, Principles, right, of many pitch levels, and it has the Mixtures together, right? A: Yes. V: And if it has the term Grand Plein Jeux then you add the 16’ Bourdon in the manuals too. And very often you would need Cantus Firmus in the pedals, then you would need, I believe a Trompette 8’, maybe together coupled with the Flute 8’. Or if you have Clarion 4’, you could add 2’ to reinforce the sound of the pedals, but no 16’ in the pedals. A: Well, what about Grand Jeux? V: In my understanding here, it’s more of a flute sound combined with the cornets, flutes and reeds. A: Reeds, yes. V: Which means, Trumpets, then Cornet either real Cornet with five ranks, based on flute sounds; 8’, 4’, 5th, 2 1/3, right? Or you can select those five flute sounds from the manual and add them to the general plunger sound, right? Do you need the 16’ in the manuals here? I believe so. A: I think so, yes. V: Mmm, hmm. A: And what about solo registration for solo voices? What if you have tierce en taille? V: Those characteristics stops that French organs have, I think, they have specific meaning and specific function, right? Tierce registration means you use a third based on 1 3/5 sounds. But in addition to that you of course need 8’ flute, right? And then a Tierce sound, and maybe even a fifth sound to remind a little bit of the Cornet. You have to check on you balances on your organ, if it’s not your know, historical French organ, if you’re adapting it. A: Yes, and my next question would be, do you think it’s okay to play the French classical music on modern instruments. V: I think it’s okay to play whatever a person wants and likes, right? But the result will not necessarily be the same as on the historical French organ. A lot of people don’t care about that. They just love the music. A: Well should you then just follow closely to the original registration? You should look for and make up your own registration, depending on the sound of a particular organ. V: Yeah, I believe you’re right. You should listen to some recordings, not necessarily of the same piece but maybe a typical French classical registration that you are looking for, like Tierce en Taille or dialogues of the Voix Humaine or the Crumorne registration, right, or the Cornet, all those things. You could listen to a piece like that, and then check if your organ has similar kind of stops. If it’s not you have to, you know, adapt. A: Yes, but for example, if you are playing a German organ, those reeds are different from the French reeds. What would you do then? V: I wouldn’t play French music on a German organ. A: Okay. V: But you know, a lot of people think differently, and they have the right to do so, right? We’re just telling people, sharing with people our experiences, right Ausra? A: Yes. V: And you don’t necessarily have to agree with us. And I believe people who are opposed to that, their opinion might change if they try out a lot of historical organs. A: Yes. V: French, German, Italian, Dutch, Spanish, Portuguese, right? And all those areas have different styles and different types of music. A: Yes. And what is your favorite French classical composer? V: Ohhhh, a tricky question. Mmm, A: I have my favorite. V: Let’s see. Does it start with the letter called ‘G’? A: Yes. How do you know? Yes. Nicolas de Grigny. Yes, that’s my favorite. V: Nicolas de Grigny was very polyphonically oriented composer, because a lot of French composers like Couperin not necessarily wrote polyphonically advanced music. They wrote a lot of harmonically advanced pieces, and their harmony system is basically a pioneer system of the system that we used today. It’s based on the Rameau treatise, right? A: Yes. V: But Germans were more keen to the polyphony, right, just as Italians were a century later, or earlier, in the Renaissance, even in the 16th Century or the beginning of the 17th Century. But then the Italians started to play those different types of pieces, like Scarlatti, right? A: I know, it’s just like everything an opposite way. V: Polyphony changed. But Germans were more strict with polyphony with Bach and that tradition. And French were more eager to explore the sounds and the colors. A: But yes de Grigny polyphonic pieces were quite complex. You can even find 5 part fugue. V: And Bach also learned from de Grigny. He copied his Livre de Orgue and based some of his earlier compositions, Fantasy and Fugue in C Minor, for example, or other pieces, like Piece d’Orgue for example. A lot of pieces which have five part texture, they’re based on the French model. A: Yes, that’s true. V: And do you know Ausra, why French wrote five-part textures and not four-part textures like Italians? I’ve read that Italian string chamber music, was, A: I think they had an extra voice, yes? V: Italians, four parts, and then, A: Like string quartets, yes? V: Yeah, two violins, viola and the cello. But French had one extra instrument: two violins, two violas, and one violone. A: Two violas, yes, wow. That’s amazing. V: And they used different kinds of clefs. And people sometimes today like to read those clefs, right? Some crazy organists. A: Yes, like Vidas. V: Like Vidas. Are you a crazy organist, Ausra? A: Well, not as crazy as you are (laughs). V: You are sort of in between normal humans and you can relate to normal humans, right? A: Yes. V: You can read the music that normal people read. And I can do too. But sometimes, I’m not satisfied with normal stuff so, I get crazy. Alright, guys. Please explore the French classical registrations. It’s really a fascinating topic. We could actually recommend a book, right? Maybe Fenner Douglass and Barbara Oven. They both wrote interesting treatises about organs and registrations, so if you read the transcript from these podcast you could click on the link and check out those books. A: Yes. They would be a big help exploring different registrations. V: Wonderful! Thank you so much for listening, and applying our tips in your practice. This was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: And remember, when you practice… A: Miracles happen! Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. Vidas: Let’s start Episode 163 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. This question was sent by Anne. She writes: Good Morning Vidas and Ausra – I have a question for you. I am working on Bach’s Christ Lag In Todesbanden from the Orgelbuchlein (Riemenschneider Edition). The Key Signature for the Chorale is D minor (B flat) but there is no B flat in the key signature for the Prelude. However the piece is apparently written in D minor. I’m assuming it’s modal. My question is how do I determine which mode it is written in? BTW, I am working on your pedal exercise from the Bach BWV 540 in all Major keys and the Cadence transposed to 24 keys. I really like them to get warmed up on before my daily practice. Thank you so much for taking the time to do that! Thanks! Anne Kimball (Total Organist subscriber) So that’s great, that Anne is practicing all kinds of exercises from the collection that we have in the Total Organist training system, right? A: Yes. V: So, going back, Ausra, to the question about modal pieces and their key signatures--do you think that--Do you know this piece? It’s in d minor, but there is no B♭ next to the clef. But it starts and ends on a d minor chord. A: I know; and actually, this is not the only case that composers in the Baroque period did that. But it just means that the piece is written in Dorian mode, D Dorian mode. V: D Dorian. So this system, of course, is much older than the major/minor system? A: Yes, it is. And although I’m telling that this piece is written in D Dorian mode, it’s yes and no, because it already has that tonal system--major/minor system--but also preserves some features of that modal system as well. V: You know what would be modal? I think the chorale melody is modal. A: Yes, yes. V: But their harmonization--harmony, chords, and polyphony--I think it’s quite normally minor. D minor. A: So...and you know, she asks about how to determine which mode it is. So this is sort of simple: for example, like in this case, it starts and finishes on D. Not on A, as it should be if the key were a minor. So if it finishes on a different note, then you can suspect that the mode is in D. V: Mhm. And, is it a major or a minor mode? A: It’s a minor mode. V: Why? A: In this case. Because if you would take a piano--all the white keys--and start playing from each of the keys, you could get a different mode each time. V: Like from C, would be one mode… A: Yes. Maybe let’s start from A. Maybe we could talk about all of them. V: Alright. So, what kind of mode would you get if you started playing a scale with white keys starting from A? A: This would be Aeolian mode. V: And it doesn’t differ from any normal, natural minor, right? A: Yes. It’s like natural minor. And because it’s natural minor, it doesn’t have that raised seventh scale degree and sixth scale degree; it sounds modal. V: Mhm. And then, if you start with B with white keys only, it’s not b minor then. A: Yes, it’s not b minor. It’s Locrian mode. V: Locrian. I don’t think we teach that in school very much. A: Well, we don’t teach that in school. But I think it’s crazy, because actually, the head of our department, he is crazy about math. Actually, I believe that he’s a true mathematician, but not musician! V: Oh? A: Because he teaches kids that there are 3 major modes and 3 minor modes; and if he adds Locrian mode, then there are 7 modes, and it’s not right for him mathematically. But actually Locrian is a minor mode. So in that case, if you would teach it, you would have 4 minor keys and 3 major modes. 3 major, 4 minor. V: It’s not symmetrical. A: I know, and it doesn’t suit him. So...well, I teach my kids...at least I say that there is a seventh mode, too. V: Exactly. I think that you have to understand that from the B note, when you start playing the scale, it’s more minor than major, because B Major has 5 sharps from B, and b minor has only 2 sharps. A: Yes, and you can sort of imagine that it’s a minor-minor-minor key: compared to natural minor, it has a lower second scale degree and fifth scale degree. V: Aha, so even tonic triad or tonic chord is not minor there; it’s diminished. A: Yes. V: Hmm. A: It’s sort of the most awkward mode of all. V: Mhm. A: Of those seven modes. V: Very sad mode, right? A: Yes, it is. V: Saddest of them all. What about if you start from C? A: Well, you have Ionian. V: Ionian. Okay. What about...Is it different from C Major or not? A: No, it’s actually the same. V: Natural major. A: Yes, natural major. V: I see. And then from D would be our beloved Dorian mode. A: Yes, and it’s very common. Many composers actually use this D Dorian mode in their compositions. V: Why is it related to minor and not to major? A: Well, because it’s based on the d minor scale--you could say that. Only, it has the sixth scale degree raised. V: B natural. A: Yes, yes. And if you would look at the tetrachords, there are 2 tetrachords each in this mode. You have a minor tetrachord at the bottom, and then again you have a minor at the top; so 2 minor tetrachords. V: Mhmm. A: That’s why it’s minor mode. V: I see. And D Major should have 2 sharps. A: Yes. F sharp and C sharp. V: It’s more distant from all-white-keys then. A: That’s right. V: Alright, how about from E? What happens? A: You would have Phrygian mode. It’s a minor mode too; but compared to e minor key, it doesn’t have the F♯. So it has a lower second scale degree. V: Mhm. And about the F mode--it would be, what? Lydian. A: Lydian, yes. Comparing with major, that’s a major mode. It wouldn’t have the B♭, so you would have the 4th scale degree raised. V: So the last would be from G. A: Yes. V: And it is Mixolydian. A: Yes. It’s also a major mode, and you could compare it with G Major key, but it wouldn’t have F♯. So it has the seventh scale degree lowered. V: Mhm. So all those early Baroque pieces, even Renaissance pieces, were written in a modal system, right? A: Yes. V: And only later composers adopted a major/minor system. And as late as Bach, sometimes he adhered to the rules of modal writing, even though he clearly wrote in major or minor mode. A: Yes, but also, not only Baroque composers--like later composers, especially French composers, they liked to use modes, too. V: 20th century composers. A: Yes, 20th century. Composers like Langlais, for example. V: Organ music suits very well for the modal system. Somehow in my church, when I improvise, I use modes all the time. A: Yes. And if you would look at any hymnal, you would find quite a few modal hymns, too. V: Right. So guys, if you decide to check out some modes, practice them by playing just a single melody with one hand; and adapt and transpose to any other note system, starting from C or E♭, or B, or G♯--whatever starting point you can do, it’s okay. So then, your melody will have different modes. And you can transpose to major, also, related modes. Like Lydian, Mixolydian, and Ionian. Or minor related modes, as Ausra said, Dorian, Aeolian, and Phrygian. A: And Locrian! V: And Locrian, if you want to be complete. Thank you so much, guys, for listening to us. And send us more of your questions; we love helping you grow. This was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: And remember, when you practice… A: Miracles happen. Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 162 of Ask Vidas and Ausra podcast. Today’s question was sent in by John who is preparing for his upcoming April recital in our church, at Vilnius University St John’s church and he asks the following question: It would be wonderful to hear you and Ausra to speak about how you prepare for an overseas recital where you haven't played the organ before and you don't know any of the people or their culture. It’s difficult to say about the future although in July we will be playing in London, St. Paul’s Cathedral. But let’s talk a little bit about the past experiences right? A: Yes. V: Last summer we played where? In Sweden. A: In Sweden and then in Poland at the beginning of September. V: OK. So how did we prepare for the Sweden experience? A: Well you know how it is when you have internet and you have so many valuable sources and you can find out about instruments you will be playing. Quite a lot of information. But of course, the smart thing to do would be just to contact the local organist and ask him or her about the instrument. V: I suspect that when a person is scheduled to play a recital they will contact the organist anyway, right? A: Sure. V: And ask about the instrument and the style of the instrument or course. The organist might send the disposition of the stops or specification and pictures of the stop layout. A: It’s not that you will have a lot of time to practice the instrument that you will be performing as we had actually in Stockholm. And it was real nice. But even if don’t have much time or almost no practice time on that organ you can still do your registration. V: In advance. A: In advance, yes, if you have the specification for that particular instrument you can write it all down in the score before even practicing on the real instrument. V: And, when you go to the local organ there, when you arrive at the church or the instrument, then of course you will need to check and correct some things because you might be wrong or off in a few places but maybe not in the majority of places. A: Yes, and the most important thing is to choose your repertoire wisely and what I mean by saying this is you have to know what kind of music will fit and will work on that instrument. Because you know you might want to play a piece by Messiaen but the organ may not be suited for that. So you really need to select your repertoire carefully. Because you know if you will select your repertoire well then things will work out well too. V: There are two kinds of organists in the world who tour and play international recitals. One kind of organist plays on generic instruments and plays the same program over and over for one year. And then during some off months they would learn a new repertoire for the next year and then they schedule the next tour, global tour, world tour, and they do the same in different places but basically playing the same repertoire over and over. But we have to remember they normally select only the generic instruments. Not necessarily romantic ones or not necessarily baroque instruments. They’re sort of mixed instruments where you could play in a rather satisfactory manner a lot of different music. A: Well, like in Sweden there was no instrument that was suited for really baroque music. V: Why? A: Because you had meantone tuning so basically you could not let’s say play like Bach and do for example like Prelude and Fugue in F Minor. It wouldn’t work for instrument like this. V: Yes, advanced keys don’t sound well. A: So, we selected repertoire like composers like Sweelinck and Scheidemann, Praetorius and these worked very well on that instrument. But for example when we went to Poland where we played on the baroque instrument but from late Baroque times. V: 1719. A: That instrument is sort of a contemporary of Bach. V: Hildebrandt organ in Paslek. A: Yes. So we selected baroque music mainly but we selected, you know, late Baroque music like Bach Brandenburg Concerto for example and we also did some contemporary music too. V: Because even in early style instrument you could play some contemporary music which is written in a very light style. It would have to be a very transparent style, not fixed chords, not very dissonant. But we played our friend, Dutch composer Ad Wammes and his style is… A: minimalistic. V: He wouldn’t agree actually. He says his music style is influenced by symphonic rock which has this minimalistic drive. But is not like Philip Glass. A: I just can make a joke you know about any composer. If he or she thinks that no, he or she composed a piece and everybody has to think about that piece as he or she thinks. That’s wrong. You know it’s like a baby since you’ve adopted, just let it go and let it live his or her own life. The same is with a piece of music. If I’m playing this music and I see minimalistic features, that’s my opinion and nobody can take it away from me. V: I didn’t mean to take away your opinion, of course. I just wanted to say that Ad Wammes was influenced not by let’s say Steve Reich or Philip Glass but from the music by symphonic rock composers. A: It just means that that style also has minimalism in it. V: It has similar features. A: Because they have those repetitions over again so how else would you call it if not minimalism? It doesn’t matter where picked it up it is still minimalism. V: We have to double check where Philip Glass got his influence. A: Yes, that’s true. Because likely I would see half of Lithuanian composers. They are very minimalistic. It’s fairly common in Lithuania to use a minimalistic style. I also don’t think we were influenced by Reich or Glass. Maybe we were influenced by Goretsky maybe or I don’t know, Taverner, Part maybe. V: I bet Philip Glass had some influence taken from rock music, synth rock too. A: Could be. Because everything is all mixed up and all criss-cross. V: It’s called crossover music. Excellent. So, it’s really a matter of having well rounded taste in music when you select your pieces for unfamiliar instruments. Right? The more experience you have with playing different kind of styles, different kinds of music, and different kinds of instruments, the more you can adjust and see which will work and which won’t work. A: That’s true. I think it’s also very important to keep in mind that first of all, you need to show the best qualities of the organ, of the instrument itself and not your own skill. V: You don’t mean you have to play music that you don’t like. A: Well, no. That’s not what I meant. V: For example if you didn’t like early music at all would you play in Stockholm, the German church where we played last summer, on the Duben instrument from the 17th century, replica of that 17th century organ. A: No. you shouldn’t even play such an instrument if don’t like that music. V: You wouldn’t play Reubke Sonata there if you liked Reubke so much. A: No, oh no. That’s a thing of being an organist, you need to show the best qualities of the instrument. V: Right. So, you have to have the right variety of favorite styles, as many as you can. Don’t try to be a one-sided organist unless you want to have very limited choices of what to play. A: I don’t know there are many instruments in the world where you can play anything. The trouble with those instruments is that for my ear, for my taste, nothing sounds right on them. V: On a generic concert instrument. A: That’s my personal opinion, I don’t know what you think about it. V: It’s easy to play. It has combination action and pistons and multiple levels of memory. You can set in advance your combination and with the push of a button, you can do all kinds of loud and soft contrast. It is much easier for the player. But, as you say the music loses some color. Especially early type of music created before 19th century. A: I know, it is just like cooking. And using for example with each dish you are cooking you would use the same spices. Anything would taste similar. V: There are some restaurants like that. A: I know, especially those chain restaurants. V: Of course some people will not agree with us. Especially those who like concept instruments. But that’s OK. We don’t try to force our opinion on them. We just share what we think. What we like. It is not necessarily the true way. Right? In organ there is no true way. Because every instrument is different and you can try many things and see what works well. A: But I think you know if you would listen to historical instruments, if you would have a chance to play one yourself, I think even people who just play generic instruments, even their opinion might change. V: Exactly. Sometimes we receive letters from people who disagree with us that early music should be played without heels. And then I ask them if they ever played historical instrument or a copy of a historical instrument and the answer was “No.” So before even probably stating that playing early music with toes only is a nonsense, that it couldn’t be done virtuosically enough. You have to try for yourself that kind of instrument and see if you can satisfactorily with heels. And the answer will be… A: No. So you can argue but it’s like you know how can they tell if snails are tasty. I have never tried them so. I cannot discuss that question. V: Some people will not even try snails. A: I know. V: They dislike the idea of eating snails. A: I know. I wouldn’t try them myself. V: Because you know how they are prepared. It’s cruel. A: It’s just awful. V: So, for John and other people who will be traveling abroad and playing unfamiliar instruments the number one advice from my side probably would be to think over you repertory choices and if it fits the instrument well. What would your recommendation be Ausra? A: Well, you know if you are traveling to an unfamiliar organ, if you know that you will not have much time to practice on it, just choose easy pieces. Don’t try to put the hardest pieces that you have in your repertoire to play for that particular recital. Choose easy repertoire. You will just benefit from it. V: Especially if you don’t have a lot of time to rehearse on that instrument so better to choose pieces that you has played a lot of times. A: Yes, and that you feel safe and comfortable playing them. It will give you less stress during performance on that unfamiliar organ. V: Memorize your piece. A: Yes. V: And prepare your registrations in advance. A: That’s true. V: Then you will save time and then you spend quality time on the actual organ that’s given to you at the moment. So, thank you guys for listening. We are going to play some organ music now and we hope you do the same. Because remember when you practice… A: Miracles happen. If you're looking for an extra income, I recommend you look into Steemit (www.steemit.com), a social media and blogging platform where you get paid for creating and curating content. It's a perfect way to monetize your brain. In time it can become a significant revenue stream for you. It's like Facebook but 10 times better because with Facebook you only get a boost in your ego when somebody likes your content but with Steemit, it's real money. With Facebook you are the product for showing their advertisements and the only one that benefits from Facebook is Facebook itself. With Steemit is different - everyone benefits.

I've been posting there my drawings, improvisations and podcasts for a month now. Feel free to follow me on Steemit at https://steemit.com/@organduo AVA161: How To Build A Principal Chorus On The Organ At Vilnius University St John's Church?2/21/2018 Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 161, of #AskVidasAndAusra Podcast. We’re continuing our discussion about the preparations that John from Australia, John Higgins is doing in order to be well prepared for his upcoming recital in April in our church, Vilnius University St. John’s church. In the previous podcast we discussed the questions about the action heaviness, about the situation with the swell pedal, right? About English speaking listeners and if we can translate English speaking words from John that he will be saying in between the pieces, right. And now, let’s start a little further bit further. He asks: 5) How many people who might attend my recital would speak English? I'm guessing my poster and program need to be in Lithuanian and you would have to interpret any words I say? 6) Would people expect me to speak at the beginning of the recital and then play all the pieces, or is it ok to play groups of 3 pieces and introduce each bracket of three pieces? If it takes a long time to walk from the organ loft, this may not be possible unless there is a wireless microphone? 7) On the St John's organ playing Bach fugues, would you normally register the pedal with principal chorus and no couplers, plus the pedal Posaune or is this reed too loud? I am used to playing small organs more in the English style, so you always use the Great to Pedal coupler. Sometimes on Australian organs the pedal Posune is too loud for fugues, so you might use the Swell 16’ reed coupled to the pedal with the Swell to Pedal coupler, and just use the Great principal chorus in the manuals. Can you believe it's only 9 weeks to go! Look forward to hearing for you! I hope you have a lovely day, Take care God bless, John... V: So, Ausra, it’s a very simple situation, right, we have? A: Yes, we have a wireless microphone. V: No, it’s, a cord, we record. A: It’s a cord? V: Yeah, it’s an old-fashioned microphone you have to A: It’s connected to that speaker. I remember now, yes. V: So the system is this; before recital, I turn on the lights and we have the headlights pointing to both sides of the organ loft and beautiful organ facade is lighted in golden colors then. And then I take out the speaker from the inside of the organ and put it someplace close to the balcony, eh, balcony rim. And then, what happens; I connect the microphone and I recommend then probably you could do both ways: You could speak just at the beginning of the recital and then play all the pieces of your program non-stop, right? Or you could talk between each of the pieces, or between some groups of the pieces, like John says, three pieces, and then play. What would you prefer, Ausra? A: Well, if I would be listener or if I would be a player. Because you know if I would be a player then I would just talk at the beginning and then would play the entire recital through. But if I would be a listener I would prefer that somebody would speak, maybe in groups of three pieces as John suggested. V: And, I know what you mean. For a player, you concentrate better if you play non-stop. A: Yes. V: But it’s also more difficult to concentrate for an hour, right, non-stop. So if you talk and play, talk and play, talk and play, you could kind of switch actions and activities and can start afresh in each piece. A: Well it depends what is easier for you, to talk or to play. For me it’s easier to play than to talk. V: Of course, John is a great storyteller. It will be easy for him to talk. A: So what I would suggest is that he would talk , you know, during the recital. V: Mmm, hmm, as many times as he wants because we can translate it for people. Excellent! Another question that he had is that about playing Bach fugues on this organ. He says ‘would you normally register the pedal with principle chorus and no couplers, plus the pedal Posanne, or would this be too loud?’ No, I wouldn’t say it’s too loud, right? If you have, let’s say, full Principle Chorus on the great, like Principle 16’, 8’, 4’, 3’, 2’ and a Mixture, maybe some flutes, 2’, 8’ and 4’, and if you like you could add a Tierce, right? A: This is on the right side, yes. V: You could also have many stops in the pedals; 16’ Principle, 16’, another, you know, wooden stop, and then maybe full basso 8’ level, and then 4’ flaut bass, and then you could add Posanne. Right? A: Yes. V: Would you need, Ausra, pedal coupler for these two? A: I wouldn’t have pedal couplers. If I have Posanne, it is not necessary unless you want to have more pedals. V: For example, if you have a large pedal solo. A: Then yes, you could do that. V: Because at the moment our mixture, pedal mixture is not working. A: Then you could add the coupler. Great to the pedal. V: Then of course, and then you could use the pedal coupler in spaces when you need the manual coupler too. 3rd’: to the great, 3rd to the first coupler and 2 principle choruses combined then, and you would need it and you need more pedal power too. You see what I mean? A: That’s right, yes. V: If you couple two manuals, then you might probably need pedal coupler as well. A: Yes. V: Excellent. Wonderful! So, nine weeks to go for John to prepare because of course, it’s a long process to adjust, adjust to the unfamiliar organ. And we’ll be talking about the next question. How we prepare for our international tours on unfamiliar instrument, especially when we don’t have a lot of rehearsals scheduled, right? A: That’s right? V: This summer, we’ll be going to St. Paul’s Cathedral to play in London and before that we’ll going to go to the oldest organ in the Baltic States. What is it? A: Yes, it’s Ugale, in Latvia. V: Yeah. Our friend, organ builder Janis Kalnins has restored this beautiful Cornelius Rhaneus from 1601 or 1701, I forget. It doesn’t matter. 100 years older or younger, who cares... V: But you find a beautiful movable eagle. A: This reminds me of a duck, because as an eagle seems too fat. So I imagine that it’s a duck with eagle wings. V: Oh, I remember, it’s 1701. A: Yes, 1701. V: Yeah. So, but we’ll be talking about how we will be preparing for these unfamiliar instruments in the next conversation. In the meantime, go ahead and try to practice some more because it’s really a wonderful day, right Ausra? You will be playing today, some of the pieces solo, recital pieces on your program for the upcoming Bach recital, and will be playing organ duet pieces. A: Oh yes, that’s right. V: Everyone knows your playing E Flat Major Prelude and Fugue by Bach. How’s that going for you? A: Well, it’s going well. I just have to repeat it time after time just to keep myself in good shape. V: It’s not a big deal. A: Yes. It’s not a big deal. It was a big deal you know, last year when I played it after like ten years after not playing it. V: And you are scheduled to play this piece in Notre Dame in Paris, A: Yes, that’s true. V: in a couple of years. A: Yes. V: So, wonderful piece, wonderfull instrument too. And Ausra, what about our Duets? Are you enjoying the quick runs with your right hand from the Bach arias we’re playing together? A: (Laughs) Are you teasing me? V: Of course! That’s my, that’s my character, always. A: Yes, we are working on two duets from Cantata 140 which is probably my most favorite cantata by J. S. Bach. V: Wachet auf… A: Yes, Wachet auf. V: You remember, guys, BWV 645 is taken from this cantata. A: The 1st of the Schüblers chorals. V: Yes, Middle movement from the cantata. And we’re playing organ duet arrangements from that cantata. A: Yes and we are playing one which has the nice oboe ritornello? V: Ritornello? A: Ritornello. And another one which has violin ritornello. And I play that ritornello with my right hand in both of these duets, and then with my left hand I am playing, you know, one of the soloist, I think the rhythm parts of soloists. Because these are sort of like that between bass and soprano. And of that you know, ritornello of the solo instrument. And then of course there is the continuo parts. So with this playing the continuo part and doing one of the soloists, the bass soloists, and I’m doing the other two. So my, my sort of role is small, virtuoso and I’m not enjoying it so far. Maybe I will when I will learn the text. V: Are you enjoying the third eye, I remember from, it’s called Mein glaubiges Herze. It’s Cantata No. 68. But we have to read from the C clef. A: Yes. Actually it’s okay because when I have the C clef I have only one voice. And then later on when I have the two other parts and two voices I have two treble clefs so that’s fine with me. What about you? V: In my part of the third, this aria, or duet, probably I need only two bass clefs, no C clefs for me. Umm, which is easier then. But I don’t mind C clefs. I enjoy them. It takes a little more time to get used to them, especially in, you know, live situation, when you play in public. But it’s not a big deal anymore for me. But playing together with you is really fun, especially to see how your right hand is running all, in all passages up and down. A: Yes. And now when we’re talking about clefs, I remember a funny story we had that just happened when you just started learning your organ book. I remember you were talking about or writing about clefs, and instead of bass clef, you just left that ‘B’ letter, you know, just by accident. V: Ah, I see. A: And, and when you did the spell check it still, you know, showed it’s okay because such a word exists. And then you received a letter from one of your readers, you know, telling you, ‘O Vidas, look at this! Was this a new class that starts not with the ‘B’ letter but with the letter ‘A’?’. V: Exactly. A: it was so funny. Funny, funny joke. V: I felt embarrassed. A: I know. V: But uh, I corrected my, my typo right away. A: Yes. That’s funny. V: Excellent, guys. So we’re going to stop this recording now and go ahead and practice some duets and solo pieces. And we hope you do the same, right? A: Yes. V: Please send us more of the questions. We love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice… A: Miracles happen! Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: We’re starting Episode No. 160 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. This question was sent by John, and he writes: Hi Vidas and Ausra, How are you today? I am quite excited I have almost finalised my program for April 7th and I am designing a poster/invite for the recital. I wanted to ask a few questions: 1) is this score attached the correct one for the Lithuanian national anthem? I'm trying to learn some basics about your country. Does the piece end at the end of the score or does it repeat some of the phrases? 2) Could you please send me some photos of the stop jams on the St John's organ so I can be more familiar with the layout? 3) Does the St John's organ have a balanced swell pedal on the swell division or is it a trigger lever pedal off to the right hand side of the pedalboard? 4) How heavy is the mechanical action, I remember one of your podcasts was with an American organist and he said it was the heaviest he'd played. So, how are you today, Ausra? A: I’m fine. V: What does that mean? A: I just feel fine. V: Do you feel better than yesterday? A: Well, yes, I feel better. Because today is Saturday, and I don’t have to teach classes, so I’m very happy. V: Exactly. Yesterday was quite a strenuous day for you, right? You played for diploma ceremonies. A: Yes. And because I had to go to that ceremony right after five classes that I taught in school. It was a very busy and stressful day. V: Yeah. We have to think about our planning for the upcoming Bach’s birthday recital, which also will be in the evening of Friday. A: Yes, it will be hard, actually, to play a recital after a working day. V: So, John writes those questions because he is coming to play a recital at St. John’s in April. A: Yes, in April. I’m looking forward to finally meeting him in person! V: Exactly. So this is really exciting. And we feel that we know him and his family well through, what, six years of interaction? A: Yes. V: But never having actually, physically, met him. A: Sure. V: So that will be the first time. We spoke with him on the podcast--at least I did--but, of course, we both read his emails and feedback he sends frequently. So we feel like we’re very much connected to his experience in Australia. A: That’s true. So now, let’s help John to get an impression about what our organ is, and how he needs to prepare for his recital. V: Exactly. A: So, maybe we first will talk about the action. V: Yes. But before that, he also asked you--or asked us--“Could you please send me some photos of the stop specification of the St. John’s organ, so that I can be more familiar with the layout.” Of course we can do that. The layout is very simple, if we can just say a few words, right, off the top of our heads. When you sit on the organ bench, you face the music rack; what do you see to the right hand side, Ausra? And to the left hand side? A: Well, you see stop knobs. And there are like 4 rows on each side, of stop knobs. V: Vertically. A: Yes. They are all vertical; and sometimes it’s hard to pull them out, because they are sort of heavy mechanical wooden sticks. V: Mhmm. A: With knobs at the end. So...And then, the principle is that the farther from your both sides are the pedal stops. V: Mhmm. So, it’s a symmetrical layout, right? A: Yes. V: The closest row to the organist is the Great. A: Yes, the Great, or the first manual, actually, because on many organs in other countries you have the second manual is called the Great, but here the first manual is the Great. V: Okay. What’s the next row, then? A: Then you just keep moving up. So the second row is the second manual.. V: That’s the swell pedal. The swell box. A: Swell box. And the swell box is located right in the center, in the middle of the pedalboard. V: Between E and F notes. A: Yes. V: Of the tenor octave. A: Yes. And actually, it opens fairly easily. V: It opens up when you… A: Push down. V: Push...just like accelerator pedal in a car. Right? A: That’s true. V: Because there are opposite systems sometimes--when you open the box, you have to press with your heel, not with your toe. A: Yes. Then the third row on both sides is the third manual. V: Mhm. A: Which is sort of a little bit imitation of a Great, and actually the first and the third manuals, they are very well suited for Baroque music, for early music. And the second swell division is small--you know, suitable for Romantic music or later music. V: And we have to remember that the third manual is positioned on the highest level of the organ… A: Yes, it’s Oberwerk, basically, compared to German organs. V: And the scaling of those principals in the Oberwerk is rather narrow. So we have to keep in mind when registering any kind of music, because normally, we double them--Principal plus Flute of the same pitch level. A: Yes. V: And it’s a more rounded feeling. Even though it is Baroque-like. A: Yes. And what else could we tell about our organ? That on the left side, louder stops are located. V: More principal… A: Yes, more principals, mixtures, and you know, loud reeds, and… V: With the exception of Bombarde. A: Yes, and Unda Maris is on the left side, too. Yes, on the left side which is [? 8:37]... V: And..go ahead. A: And on the right side we have like, string stops, and flutes; softer reeds, like Oboe on the Swell division.. V: Vox Humana… A: Vox Humana, and of course, with the exception of Bombarde, as you talked about. V: Bombarde is on the Great. So here on this organ we have 16’ stops on every division. A: Yes, so you basically can have a pleno on each single manual. Of course, we have manual couplers, too; but basically, you don’t have to use them. V: Mhm. A: I actually don’t think any of those couplers are really needed for this instrument. But of course you can use them, if you need them. We have pedal couplers, and manual couplers. V: Yesterday evening, I just had a chat with an organist who will be playing a recital tonight, and he is going to play a lot of Romantic pieces, including Sonata by Roethke, on this organ; and he loves to play with couplers. And he, you know...not complained, but was sort of a little bit worried that the action then becomes extremely heavy. A: Well, don’t play such repertoire on this instrument. It’s highly unsuited for Roethke’s Sonata, or for, I don’t know, Vierne’s Symphony. V: It could be done. But… A: But the result won’t be...will not be satisfying. V: Unless you just love a big sound. A: Because especially, you know, the Swell division is very heavy. V: Yes, because… A: And you cannot play Sonata by Roethke without Swell divisions. So...I wouldn’t play music like this. V: The tempo must be slower then, because of the acoustics, also: 5 seconds of reverberation. A: I think, like, Brahms, Mendelssohn, Liszt, sounds nice on our organ; but probably not the pieces beyond that--not like Roethke or Vierne. Or Franck… V: Yeah, early Romantic music works well, because of the Kirnberger III temperament, of course. A: Yeah, so you know, for anybody who selects pieces for our organ, I would suggest that three accidentals are, you know, the most--the top of accidentals that you choose in your pieces. V: To get the best result. A: Yes. V: You can play anything on this organ--even Volumina by Ligeti. But...but, you know, will you like the result? Will your listeners enjoy the result? It depends, right? If you compare this organ with a real Romantic organ, where you could play, you know, German Romantic or French Romantic music extremely well, then this organ is more suited for the Baroque organ. But if you compare St. John’s organ with a neo-Baroque instrument--like we have several of those in Vilnius--then of course our instrument is superior to these neo-Baroque organs, even for Romantic music. A: That’s true, because we have nice flutes, and nice string stops. So you can, you know, do a lot of things, but...but probably not Reubke. V: Well...the actual advice would be to probably see and exploit the best qualities of the instrument first; and then go ahead and maybe play some music that you enjoy the most, you know, in addition to that. Because you have to play what you enjoy, right? A: Yes, that’s true. V: Especially if you enjoy Romantic music, and you would only have to play, imagine, just the Baroque or earlier music on this instrument. You would suffer, you would be frustrated. But if you play a part of the program Romantic music, and part of it Baroque music, that would be like, a win-win situation! Right? A: That’s true. V: What about modern music, Ausra? Does it work here well? A: Yes, it works well. V: Better than Romantic? A: Yes, I would say that it works better than Romantic. V: So that’s the reason I keep improvising in a modern style; and it works well for me. Of course, when I improvise, I choose the layout of the stops and the stops themselves that work for my music. I adjust; I don’t force, I don’t put my music ahead of the instrument. I always listen to how it sounds, what the instrument wants. I suggest you do the same, when you play this instrument. A: Yes. V: Allright. So, another question John had was about English-speaking listeners...and, um, will we have tourists in April? A: Some, we might; not, probably, as many as we wish for, but some might attend the recital. And you know, if John wants to speak English, to introduce his program to the audience, that’s very nice; and then Vidas can translate it. We’ve had those cases in our past V: Definitely. A: And Vidas was a wonderful translator. V: We have a microphone right in the organ balcony, and we can take turns, right--John and myself. A: Yes. V: And I can introduce him in Lithuanian, and then he can play and talk, and I can translate. So guys, I hope some of these remarks were useful to you. This is not all of these questions that John sent, but since our time is limited, we’re going to discuss the rest of them in the next podcast conversation. So stay tuned for the update! Okay, this was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: And remember, when you practice… A: Miracles happen. |

DON'T MISS A THING! FREE UPDATES BY EMAIL.Thank you!You have successfully joined our subscriber list.  Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas

Authors

Drs. Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene Organists of Vilnius University , creators of Secrets of Organ Playing. Our Hauptwerk Setup:

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

This site participates in the Amazon, Thomann and other affiliate programs, the proceeds of which keep it free for anyone to read.

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed