|

Vidas: Hello and welcome to Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast!

Ausra: This is a show dedicated to helping you become a better organist. V: We’re your hosts Vidas Pinkevicius... A: ...and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene. V: We have over 25 years of experience of playing the organ A: ...and we’ve been teaching thousands of organists online from 89 countries since 2011. V: So now let’s jump in and get started with the podcast for today. A: We hope you’ll enjoy it! V: Hi guys! This is Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 690 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Andrew, and he writes Dear Vidas, My answers to your recent questions: 1. My dream is to be able to play the organ confidently in the liturgy and perhaps in recitals occasionally. 2. The 3 most important things holding me back from this are: - Poor sense of timing and rhythm - Lack of focus and concentration in practicing - My legs are both slightly twisted outwards, which makes some pedaling uncomfortable (especially around the middle of the pedalboard; I cannot place my knees close together without great effort) Nonetheless, I am finding Total Organist a very useful resource and community. I find your daily emails especially helpful. My best wishes to you and Ausra from England, Andrew V: That’s very nice to have a Total Organist community member write a message like this. A: Yes, very nice indeed. Thank you, Andrew. V: And I know this Andrew writes sometimes in his daily responses to these questions in our community on Basecamp, which is very good. A: Sure, that keeps community spirits up. V: Yeah, if nobody wrote, only we, or even if we were silent, so it would be like an empty house. A: That’s true. V: Now a few more people are participating. Not everyone, though. Some people are just, you know, reading perhaps. Not actively participating and engaging. But those who are participating, I think they are getting quadruple results, because they are thinking about their own practice deliberately, right? The question, for example, ‘What did you do today in organ playing?’ right - sometimes if you don’t think about anything, you don’t have anything to write about if you don’t play. And if you don’t have an answer for this day, and you get the same question tomorrow, the day after tomorrow, maybe you start thinking, “Oh, maybe I start practicing, have to start practicing,” right? Because Vidas and Ausra are sending these questions for me. So that’s really nice that Andrew is an active member of the community. So Ausra, start with some recommendations, please. A: Well, as Andrew says, three important things that are holding him back - poor sense of timing and rhythm. I think that’s the thing that you really need to work on, because if you are a church musician and accompanying congregational singing, then the sense of good timing and rhythm is crucial. And I think in general for musicians, sometimes people think that the right notes are the most important thing. And of course they are very important, but I think the rhythm comes above all. V: That’s because in any given piece in any piece from the Common Practice Period, rhythm gives probably, we would say, ‘flow’ of the melody. And if you lose the sense of flow, you cannot understand the melody. If you lose a little bit of notes but you keep the sense of flow, the melody, the sense of the piece is still intact, right? A: Yes. And you know, from my experience of many years playing myself and teaching others and listening to others, I could say that there are very few people with a really poor sense of rhythm. Usually, if you cannot keep good rhythm, it means that you don’t listen to what you are playing. V: And a way of listening to your playing is actually actively counting. Counting the beats and subdividing the beats if the piece is difficult. A: And yes, actually you need to do it aloud at least at the beginning. And later maybe you just use your tongue, subdivide with your tongue. And by subdividing, what I mean is the smallest value, rhythmic value in the piece is sixteenth, you need to subdivide everything into sixteenths. It might seem crazy for you at the beginning, but that’s a very good way not to lose the rhythm and be precise. V: And one example would be like this: one ee and a, two ee and a, three ee and a, four ee and a, in 4/4 meter. A: Yes, and it doesn’t mean you have to do it for the rest of your life. But for a while yes, until you get a good sense of the rhythm. Another thing, if you are accompanying the hymns for congregation, you really need to sing them. Because if you will sing with congregation, maybe not loud, but just for yourself in your head, then you will know where are the best spots to take breath, and naturally it will help you to be better while accompanying hymns. And of course with your solo pieces too, you need to basically sing each line. Remember with Pamela Ruiter-Feenstra, she pushed us to sing each line. And occasionally she would ask for us to sing. Not for example the melody, but tenor voice, let’s say. V: While playing or while not playing? A: Both ways. So I guess this should help you to improve on the timing and rhythm. Because some people will just say, ‘Oh, just put the metronome and practice with the metronome.’ I don’t think this is a good approach. Maybe sometimes just h to check if your tempo is correct, then yes. But not playing all the time with the metronome. I don’t think that’s the right approach. V: Mm hm. And his second challenge is lack of focus and concentration in practicing. A: Well… V: Which could be improved regularly, by regularly doing the same thing over and over. A: Yes, and I think if you start count and subdivide, and do all the things that we talked just before this, I think this will help on your focus and concentration. Because this constant counting and subdividing keep you concentrated in your practice. V: I agree. And of course the third problem about his legs twisted outward, there’s nothing he can do, obviously. A: I know, but you know, somehow people always complain about their legs, like they are looking inward or backward or whatever. I had a student at UNL when I was a doctoral student. He was majoring in piano performance, and he was also a doctoral student in piano performance. And he was a very tall man with really long legs. And he would keep complaining to me about his legs every single lesson. It just drove me mad, because I’m a sort of short person with short legs, but I never complain, although it gives me physical difficulties too. Remember the last recital on the Edskes organ, where you could not regulate the organ bench. You could make it higher, but not lower. V: Mm hm. A: And remember me playing that Druckenmüller piece , Prelude and Chaconne in D Major. V: You had to literally, physically shift your body to the right. A: Yes, basically I was jumping on the organ bench sometimes in order to reach the pedal on the lower level or the higher level. But I did it, and it was fine. It was clean and clear and everything was just nice. So you really have to adjust depending on what kind of body you have. But please don’t feel that you have to hold both knees always together. I think that’s such a wrong idea. And before going to the states, I didn’t even know that such a rule exists. But in America, everybody’s crazy about this idea, that you need to keep your knees together. And for me physically, that’s just impossible. Because basically my hips are too fat I would say. And to holding knees always together would make my organ playing and pedaling simply impossible. So basically I just don’t worry about it. And in Baroque music, while playing Bach, I just don’t know how this could help you to make a good articulation in the pedal. V: The probably more important than keeping knees together is to try to play with the toes, the big toes of the feet in that portion of the feet. Not sure if it’s possible for Andrew, because he says his legs are twisted slightly outwards. But see what he can do, right? How much he can shift his feet, how much he can play with the inner portion of the feet. A: Well, because you really need to adjust every rule to yourself and not to blindly follow it, but to see what works for you and what does not work. V: Yes. It wouldn’t be placing knees together, but it would be in that direction a little bit. Whatever is comfortable to you. A: Yes. And maybe you need to adjust the height of the bench better, or to sit closer to the manuals. You just need to experiment to find what works best for you. And actually your body will tell you, because if you are keeping your knees together and it’s causing you pain or really you feel very uncomfortable, then don’t do that. Don’t follow it blindly. V: Yes. Always stop and rest before you’re tired. And that would be the best way to practice also. So thank you so much Andrew for your question and answer, and being an active member of the Total Organist Community. This is really precious. A: Yes, thank you very much. V: And remember, when you practice, A: Miracles happen. V: This podcast is supported by Total Organist - the most comprehensive organ training program online. A: It has hundreds of courses, coaching and practice materials for every area of organ playing, thousands of instructional videos and PDF's. You will NOT find more value anywhere else online... V: Total Organist helps you to master any piece, perfect your technique, develop your sight-reading skills, and improvise or compose your own music and much much more… A: Sign up and begin your training today at organduo.lt and click on Total Organist. And of course, you will get the 1st month free too. You can cancel anytime. V: If you like our organ music, you can also support us on Buy Me a Coffee platform and get early access: A: Find out more at https://buymeacoffee.com/organduo

Comments

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start Episode 192 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. And today’s question was sent by Robert. And he wrote a response to my question about what are his organ dreams, and the challenges that he’s facing in his organ journey. So, he writes: 1. I'd like to perform, occasionally, in public and perform concert-level pieces. 2. Major holdback is a lack of adequate practice organs, and someone to actively listen to my practice. Hmm, interesting. So, that’s a very natural dream, right? To be able to play in public? A: Mhm. yes. V: Concert-level pieces. For that, of course, he has to develop a large repertoire. What else? A: Yes...and you know, for his first performance, he could sort of mix pieces. Not necessarily play all the hard stuff, or long stuff. V: Exactly. And not necessarily even a full-hour recital. You could play 30 minutes. A: Yes, and it always depends on what audience you’re playing to, too. Because not everybody appreciates long-lasting and difficult music. From the audience, I mean. V: Mhm. A: That sometimes, people enjoy hearing lighter music. V: You know what I would do if I were a beginning organist, but would love to eventually play in public: I would probably go to find friends in local churches, and then ask for occasional performance opportunities in the liturgical setting. What I mean is, I would play a postlude or a prelude or communion piece, or even an offertory, once in a while--maybe once a month. One piece or two pieces--it doesn’t have to be long, right? 2-3 minutes. So basically 2-3 pages of music--that would be enough, and enough to keep me motivated, at first. A: Yes, that’s true; but later on, you would have to keep going with concert repertoire and more complicated pieces. And what I would also suggest, maybe you can find somebody who will help you to perform together--with you, I mean another instrument or you know, a soloist. That way you could do, let’s say, half a concert of your solo music, and half a concert with your soloist. V: Exactly. Even if this concert itself would be short. A: I know. And that way, usually when you accompany, it’s easier. V: Yes, maybe without pedals. A: True. V: But he writes that he can’t find adequate practice organs, right? In his area. So maybe he could go to one of the churches, and ask for permission to practice there occasionally, maybe in exchange of playing some services. It’s a volunteer work, right? A: Yes. But I remember in my study years in Lithuania, of course I did not have enough time on the organ as I wanted or as I needed; so what I did was I practiced my organ pieces on the piano, too. V: Of course, we don’t know if Robert has any type of keyboard at home. A: But I think it’s easier to get, let’s say, piano, than organ. Don’t you think so? V: Generally speaking, yes. Or maybe a keyboard, an electric keyboard. A: So that way, you could save some time, and do some work on that kind of keyboard. V: What some of our Unda Maris studio students do: they print out our paper pedals and paper manuals, and play at home on the table and on the floor. And not all of them do that, because you cannot hear the sound. But people who are persistent, and have a big vision--they would rather do this instead of skipping practice. A: Yes, that’s true. So, you know, you can find various, most unexpected solutions to your problems! V: And it’s just temporary--I don’t think you would play all the time on paper, or an electronic keyboard. Maybe it’s just for a month or two, until you get a better solution. A: And I think, you know--if you would do some part, or the largest part, of your practice at home, in any way, or at least be able to play notes smoothly (not making too many mistakes), then you will not feel embarrassed when somebody would be listening to your practice. And this was a problem, too, for Robert, as I understood from his question. V: Umm, I’m not sure I’m following you. That he would love that someone would actively listen to his practice, right? Like a coach? Or not…? Or do you understand that somebody is listening, and he is embarrassed? A: That’s how I understood this part of the question. Maybe I… V: Ah, could be both, actually. Could be both scenarios. A: Yes. V: If someone is listening to his practice, it means that he has an instrument on which to practice. That’s good, right? A: I know. But you know, if you don’t have somebody who would listen to your practice and would advise you what to do or what not to do, and how to play, you could record yourself. V: Absolutely. A: And listen to your playing. And you know...you will hear some things that you will probably not like; and then you will change them, and improve them. V: You know, the funny thing about recording yourself is that before you do that, you think, “Oh, you play so well sometimes, you are proud of your achievements because you spend so much time on the organ bench.” And...sometimes you cannot really hear what’s happening until you record yourself. And don’t even listen to yourself right away, but after a few days--after you forget that feeling of that practice. And then you sort of listen to that recording as a stranger, and then you can be more objective. A: Yes, that’s true. And also, some people who are very modest might have a very bad opinion about their performing, about their performance. And this might change, also, after listening to their recordings, that, you know, they listen and, “Oh, I’m playing actually quite well!” V: So it depends on how you judge yourself. A: Yes, and what your character is. V: If you’re a perfectionist or not. A: That’s true. But either way it would be useful, for yourself to record your playing. V: Are you a perfectionist, or not? A: I will not dignify this question with an answer! V: We know the answer, though! And...was it difficult for you to let go of the feeling that you might not be perfectly prepared for the public release of your recording? A: Yes. V: You have to let go of your imaginary mistakes. A: Yes, that’s true. V: Sometimes those mistakes don’t’ kill you, you know. A: Yes. Sometimes they do. V: Hahaha! What do you mean? A: I’m just making fun! V: I see. Yeah. Sometimes, people, if you put a recording on YouTube, you can receive some nasty comments. And I don’t recommend replying to those comments at all. If you don’t like negative feedback, ignore those comments. And you can even mute comments, and let them vent anywhere else, on their own channel. A: But you know, from my experience, I think that people who give other people negative comments, they actually cannot play well themselves. V: Absolutely. And in my experience, whenever I listen to YouTube videos, sometimes I encounter not-so-well-performed pieces, right? But I never, ever have complained about that performance level, and never said, “Oh, you should not play the organ,” or “Just keep it to yourself, I’m embarrassed,” and things like that. Never. You know? Because I know what it takes to play well. A: Yes, that’s true. V: Or what it takes to play badly, right? A: I know. V: So it takes thousands of hours. And if that person was brave enough to put that recording out there, and feel vulnerable, that’s better. It says a lot of you. A: Yes. V: So Ausra, let’s encourage people to publicize their own performances on the internet. Okay? A: Okay. V: So, encourage! A: Don’t be afraid to put your recordings on the internet! V: Exactly. You actually will feel stronger about yourself, once you are doing this for, let’s say, a month or two. You kind of feel resilient to feedback and negative comments. A: Yeah, so just lose the comments! V: Exactly. Thank you guys, this was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: We hope this was useful to you, right Ausra? A: I hope so. V: Please send us more of your questions; we love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice… A: Miracles happen.

Vidas: We’re starting Episode 48 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. And today’s question was sent by Nadine, who writes, “What does it take to become a concert organist?” That’s a very broad question, probably.

Ausra: Yes, so let’s try to maybe narrow it down, to see the basics. First of all, I think you should be very good at the instrument. You must play very well. Vidas: Let’s be specific. Let’s look at our lives. Can we describe ourselves, or consider ourselves, as concert organists? Ausra: Well, yes, I think so. Vidas: We do many things, of course. We teach, we perform...sometimes we even play for liturgy (when they ask us, but that’s not often). But definitely, concert playing is a significant part of our activities. So Ausra, what did it take for you to reach this level, that you are today in? Ausra: Well, practicing for very many years. And, of course, knowing different styles; understanding different instruments; knowing how to make a registration...Having a degree, I would say, too. Vidas: Is having a degree in organ playing and performance a must today, or not? Ausra: Probably not so much today, now; but it was in previous times, definitely. Vidas: Of course it helps if you have a degree, because you have formalized instruction, and hopefully, quality instruction, right? Because not in every college, not in every university or conservatory, do you have the best instruction, right? You might have a degree, but you don’t have skills! Ausra: Yes. Vidas: You definitely must have skills. And what Ausra is mentioning, that you gain those skills from constant practice, and then putting these skills into public performance situations, sometimes big, sometimes small. Maybe start small. Ausra: Yes, definitely you will not start performing at Notre Dame in Paris! Start at your church, a local church. Vidas: Exactly. Ausra: Put some of your videos on YouTube. Vida: Now, nobody’s stopping you, right? Everyone has, probably, quality video editing equipment in your pocket--in every pocket! So just share what you can record with the world, and this will motivate you to practice even further, to get better, and to even deal with performance anxiety a little bit--because you know that somebody else is recording you, and will be listening to you in the future. Ausra: Yes, and of course, never say no to any opportunities to perform, at first. Then later on maybe you can select what you want to do and what you do not want to do; but at the beginning take every possibility that is offered to you, because knowing new organists, new instruments, might open another door. Vidas: You’re absolutely correct, Ausra. But at first, when you are nobody in the organ world, when you just practice-practice-practice, and you suddenly discover, “Oh, i have a few pieces of music that I want to play in public, but nobody has really heard of me...I have no platform,” right? So...do you have to wait for the phone call, or can you be more proactive? Ausra: No, I think you should be proactive, because if you will wait, you might wait all your life, and opportunity will not come. Vidas: Exactly, you have to find those opportunities. Of course not by spamming people, that’s rude. And people will flee from you. Ausra: It’s like fishing. Vidas: It’s like fishing! It’s no good, right? People even don’t look at those messages anymore, because the inbox is so crowded. But what you could do is simply network with other organists. Be friendly, be helpful--be helpful to other organists in your country, too, and be helpful to organists on Facebook and other social media sites. And when you share your work constantly, they start to remember who you are! Ausra: Yes, I think these times there are many small opportunities to organists-- Vidas: Exactly. Ausra: --To advertise themselves. Vidas: It’s of course a lot of competition… Ausra: Yeah, that’s true. Vidas: ...because everyone can do this, now. Everyone can post on Facebook and YouTube. But you can stand out. You can do things that nobody else is doing. Ausra: Yes, maybe, you are playing specific repertoire, and you are interested in a specific country, let’s say, or composer. Vidas: Become an authority on a specific angle of organ repertoire. Ausra: This might help you to stand out. Vidas: Like a brand. Become a brand, and your name will be associated with the thing that you do. If you do everything moderately well, you will be like everybody else, which is nothing, really--no good, because you will have to compete. But if you avoid competition and do something entirely different--let’s say, you play your own compositions. Of course, then you have to make sure your compositions have high quality, and people want to hear them; but, you know what I’m talking about, Ausra, right? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: Do something else that nobody else is doing. And that will lead you to the success of getting more recital engagements. At first you have to ask, right? Sending a lot of messages to other people, to concert organizers. Ausra: And be prepared to hear a lot of no, and probably to play for free... Vidas: And of course you’ll get rejected maybe a hundred times, but maybe one hundred and one will be successful. Never give up on this. As we say, don’t spam people; basically, format your message in a way that it would be foolish to refuse. That’s not spamming, that’s actually a favor; you’re doing them a favor by providing them a proposal that they would be actually foolish to refuse, because the entire community of their organ concert opportunities and congregation will benefit from this proposal. Ausra: That’s a very good idea. Vidas: Just turn around and think about what kind of benefits you can propose to the concert organizer. Don’t be selfish this way. Don’t just simply write, “Oh, I want to play in your church, I want to do this,” right? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: Think what’s in it for them? Ausra: But I think the more you’re willing to give to people, the more you’ll get back, for yourself. Vidas: For example, one idea would be: How about you collect donations, and give those donations to the church, or to the organ which needs restoration, right? And you think of a larger-than-yourself goal. Or maybe give to charity. Maybe you donate to some charitable organization, maybe an organization who tries to raise funds to get clean water for Africa; or food for starving children; or maybe invent some medicine for people who are having diseases today. Think bigger goals, and those will actually differentiate yourself from other organists who are simply selfish. Ausra: Yes, and let us know how things are going for you--have you succeeded or not? And we wish you well! Vidas: And of course don’t forget to share your work. And one of the best ways we’ve found to share your work is by writing a regular blog. Maybe a podcast, maybe a YouTube channel, those things that will help you create your own platform, and build authority over time. Not over one week, but maybe over several years. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: It takes seven years to be an overnight success, they say. Do you agree with this Ausra? Ausra: Yes, I agree. Vidas: Wonderful. Thanks, guys, this was Vidas. Ausra: And Ausra. Vidas: And remember, when you practice… Ausra: Miracles happen. By Vidas Pinkevicius (get free updates of new posts here)

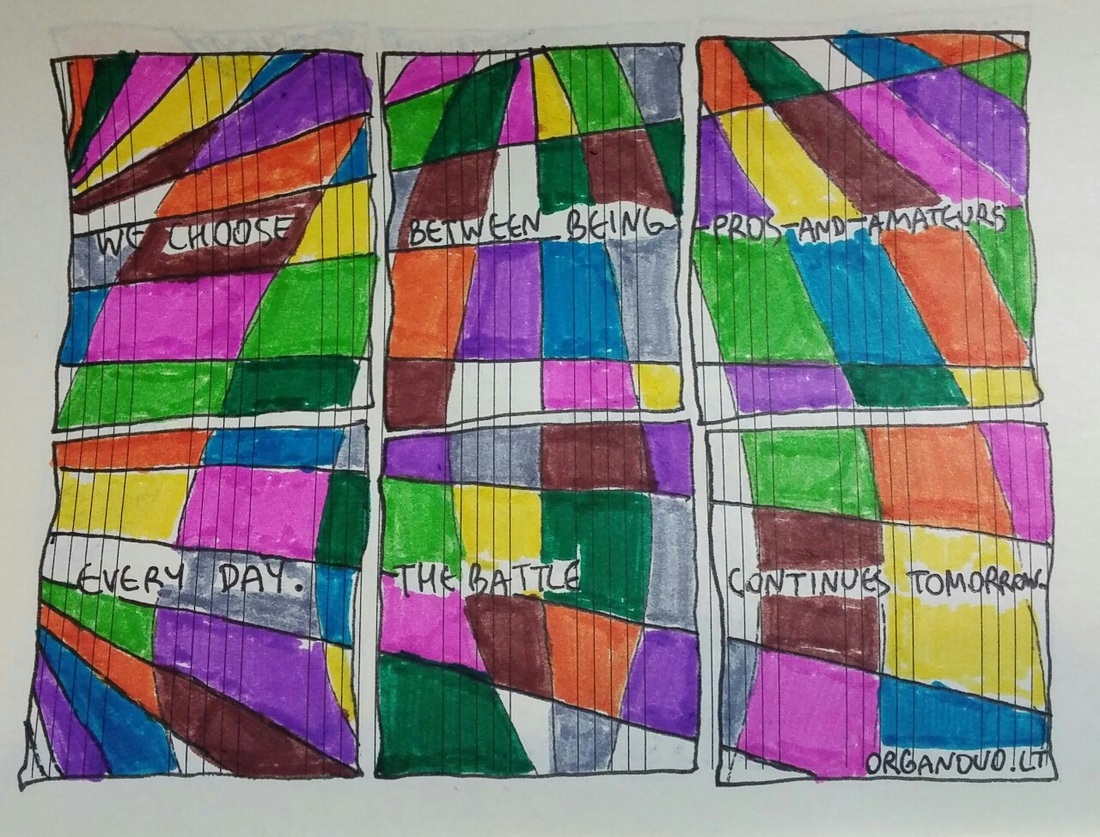

There are at least 3 ways amateurs are different from professionals: 1. Amateurs take mistakes and failure personally ("I suck at this"). Pros don't take it personally ("my work sucks"). Failure is part of the process. 2. Amateurs practice until they get it right ("1 or 3 or 5 repetitions and then I'll move on to the next thing"). Pros practice until they can't get it wrong ("10 or 100 or 1000 repetitions or whatever it takes"). 3. Amateurs are easily swayed from the plan by unforeseen life events ("I don't feel like practicing today"). Professionals adjust the plan constantly ("OK, if I can't practice in the morning, I will practice during my lunch break or in the evening or on the table when my family is asleep. Even for 15 minutes.") The good and the bad news is that we have a pro and an amateur inside of every one of us. We only have to make this choice today. Tomorrow will be another battle. [Thanks to John] Welcome to episode 23 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast!

Listen to the conversation Today's guest is Beth Zucchino, who is the founder and director of Concert Artist Cooperative, an international association of soloists and ensembles which has been advertising together for going on 27 years. She is also the designer and caretaker of Creative Arts Series, a diverse and embracing northern California based outreach for all ages and abilities with a primary focus on the organ and its literature. In the summer of 2014 Beth became the dean of the Redwood Empire AGO chapter – Sonoma, Napa, Mendocino and Lake Counties, to save the chapter from acquisition or dissolution. Residing with her immediate family, along with their llama, three alpacas, three rabbits, two cats and two dogs on Jacob’s Jamboree mini farm in Sebastopol, she extends their peaceful country environment to visitors from near through far and around the world. In this conversation, Beth will share her insights about what it takes to lead Concert Artist Cooperative, what it takes to manage a diverse group of soloists and ensembles from around the world, and what it takes to organize organ events in this ever changing organ landscape as it is today. I apologize for some high-pitched static sound you are hearing in this recording (we've had a mysterious time with technology that day). It's not loud, and I hope the words of Beth and mine will be clearly audible. Enjoy and share your comments below. If you like these conversations with the experts from the organ world, please help spread the word about the SOP Podcast by sharing it with your organist friends. Relevant link: concertartistcooperative.com Can you become a world-class organist, if you lack enough sheet music, enough guidance, and organ practice videos, and you live in a country where Internet access has only 16.2% of the population but rising (2013 data)?

This question clearly comes from a person who basically faces one big challenge - he or she is starting an entire culture (internal or external) in a place where there is no support for it (yet). Being the first is scary and costly but being the last is scarier still and costs even more. It's a scale issue - you can't become great doing great things without first becoming great at doing small things. Therefore, when you face such challenge you've got to start small. If you do small and succeed, repeatedly, you get the privilege to do medium. Do enough medium successfully and you can't help but go big. What's remarkable about the developing countries is that despite all the hardships they face, people there aren't afraid to dream big. But for starters start small. How small? How about perfecting those 4 measures the way the world-class organist would do today? In 3/4 meter, 4 measures have 12 beats. Can you focus on those 12 beats only without worrying about long-term challenges? That's the first step. Complete this step, and you'll get the privilege to take the next one and the one after that. [HT to Robert] Next: Slaying inner dragons Sight-reading: Kyrie IV (p. 6) from the Mass for the Parishes by François Couperin (1668-1733), one of the most influential French Classical composers and organists. Hymn playing: God the Father Be Our Stay |

DON'T MISS A THING! FREE UPDATES BY EMAIL.Thank you!You have successfully joined our subscriber list.  Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas

Authors

Drs. Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene Organists of Vilnius University , creators of Secrets of Organ Playing. Our Hauptwerk Setup:

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

This site participates in the Amazon, Thomann and other affiliate programs, the proceeds of which keep it free for anyone to read.

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed