|

Vidas: Hello and welcome to Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast!

Ausra: This is a show dedicated to helping you become a better organist. V: We’re your hosts Vidas Pinkevicius... A: ...and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene. V: We have over 25 years of experience of playing the organ A: ...and we’ve been teaching thousands of organists online from 89 countries since 2011. V: So now let’s jump in and get started with the podcast for today. A: We hope you’ll enjoy it! V: Hi guys! This is Vidas. A: And Ausra V: Let’s start episode 674 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Maureen, and she writes, I have been working on Christmas carols. There is a Catholic church 26 miles from my hometown needing an organist. I haven't played in public for a long time. Seeing this advert has given me renewed vigour to play with a definite purpose. There is a huge part of me who would love to play again in public and there is the other part of me trying to be sensible, logical, and practical. I would need daily access to the organ and the energy to meet the challenge. I don't drive; I haven't played in years; I don't know whether to let the priest know I can play a church organ with time to familiarise myself with it. What would you do? V: So Maureen is a member of our Total Organist Community and basically she’s wondering whether to pursue this dream of playing organ in public, right, Ausra? A: Yes, and I would say, just take this chance. Because another opportunity may never come to you. And I think you need to see as many years in life as you can, because you can always, if after trying something will not work for you. But if you will not try, then you will never know if that would have worked for you. And you might even regret that you haven’t tried it. V: Yes, I agree with you. And this is because we often think that our limits are low, you know, when we are practicing at home. That we can do certain things and not more. But surprisingly, when the situation has more risk like playing in public, at church or in concert, if you’re able, and then somehow you get more ability to play for other people, right? You discover you have some kind of inner power you didn’t think you had. A: That’s right. And you know, maybe Maureen can practice in her hometown. But to go to perform in public in that Catholic church which is 26 miles away from her hometown. Because she’s not driving, maybe somebody can give her a lift. Maybe somebody from that congregation lives close to her hometown. V: Absolutely true. Usually, in Catholic liturgy, people are required to play hymns, some acclamations, what else…maybe… A: Parts of the Mass of course. V: Parts from Ordinary Mass, yeah. And sing some psalms, I don’t know if in her town this is the case, but in Lithuania, Poland, for example, organist also has to sing. A: But I think this is unique for Lithuania and Poland. I don’t think in other countries Catholic organists also sing psalms. V: You might be true. You might be right. A: Actually, in Lithuania it’s more important to have a good strong voice than to be able to play well. V: Right. So probably Maureen should be thinking about playing hymns. A: Most likely, yes. V: Playing hymns in time well, with good leading, sense of rhythm. It could be actually beneficial practice for her to record her own singing - for herself, you know - starting from a certain pitch. Then later she could play that recording to herself and accompany her voice with the organ. Meaning that you, an organist, cannot drag or change the rhythm because the melody is sung by people already. What do you think, Ausra? No? A: I don’t know. Never thought about it. V: You know, you pretend that you are your own congregation in that recording. I can test on you. A: (laughs) V: You can sing for me, and I could accompany you. A: I know when I played at church, did many hymns, I would sing myself. But not loud. V: Mm hm. A: But inside of me I always was singing because that way I can pick up the right tempo of a hymn. V: That’s a good idea, too. Sing inside. A: Yes. V: With your inner voice. And I guess the test that I was suggesting wouldn’t work for us, because you know me and I know you, and you would adapt to my playing, and I would easily adapt to your singing. It has to be like a stranger person, who would not bend to your playing that much. So that’s why I suggested doing recording first of your own singing, and then playing it back together with your accompaniment. A: Well you just need to accompany really loud, and don’t listen to what congregation is singing. That way you will be a leader and they will have to listen to you. V: Well, exactly. It’s a good idea. Interesting question for discussion, maybe for another time: An organist…is an organist a leader or a follower? Accompanist or somebody who leads? A: Well definitely I think the organist should be leader in hymn accompanying. And you can follow somebody who sings, if it’s a soloist, then yes you need to follow with accompaniment. But if you’re leading the congregation singing then you need to be a leader. V: How is it different from soloist - following a soloist - accompanying a soloist? A: Well, it’s much different, a lot different, because it’s only one person, the soloist. And then you can adapt and follow him or her. But if it’s entire congregation, no. If you will start to listen to congregation too much, it won’t be good. V: It’s like in classroom? A: Yes. There needs to be one leader. V: Like you. Teacher. You are teacher for 15.5 years, right? A: Well no - in general to count all the years that I have taught, it would be 22 years. V: 22? A: Yes. V: Wow. A: So I’m done with teaching for now. V: For classroom setting. A: Yes. V: Mm hm. Yeah. If you have a lot of students in the classroom, you have to lead. But if you have just one-on-one lesson, you can listen. A: You still need to lead. V: But you can listen more. A: If you are a teacher, you always need to lead. V: But there is more room for listening, I think, one-on-one. A: Well yes, but I don’t think this is related with the hymn accompaniment. V: Oh it is related. Much related. Same principle, human psychology. What do you think? A: You know what I think. V: (laughs) Okay, okay! So we have different ideas with Ausra, but maybe that’s good because people who are listening also have different ideas, not always agreeable one of us. And they can choose whom to agree with. Tell us sometimes - we need feedback, right? Whom do you agree with more? A: (laughs) Well I think the truth is probably somewhere in the middle between us two. But I remember once - remember when you played hymns too fast in one of the churches and you lost your position. V: And…so I was a leader. A: Yes. V: And I lost the position. A: Yes. V: (laughs) A: But maybe that’s a good thing because I don’t think that congregation was worth your time. V: Bingo! Yeah, if they don’t want you as a leader, maybe they are better with somebody else. So thank you so much, Maureen, for this very thoughtful question. And we hope this was useful to you and maybe a few other people who are thinking of playing in public, in church liturgical setting. So please send us more of your questions. We love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice, A: Miracles happen. V: This podcast is supported by Total Organist - the most comprehensive organ training program online. A: It has hundreds of courses, coaching and practice materials for every area of organ playing, thousands of instructional videos and PDF's. You will NOT find more value anywhere else online... V: Total Organist helps you to master any piece, perfect your technique, develop your sight-reading skills, and improvise or compose your own music and much much more… A: Sign up and begin your training today at organduo.lt and click on Total Organist. And of course, you will get the 1st month free too. You can cancel anytime. V: If you like our organ music, you can also support us on Buy Me a Coffee platform and get early access: A: Find out more at https://buymeacoffee.com/organduo

Comments

Vidas: Hello and welcome to Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast!

Ausra: This is a show dedicated to helping you become a better organist. V: We’re your hosts Vidas Pinkevicius... A: ...and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene. V: We have over 25 years of experience of playing the organ A: ...and we’ve been teaching thousands of organists online from 89 countries since 2011. V: So now let’s jump in and get started with the podcast for today. A: We hope you’ll enjoy it! V: Hi guys! This is Vidas. A: And Ausra. Vidas: Hi guys! This is Vidas. Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 647 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Nabil, and he writes, 1) My dream is to be a great concert Organist, and to be one of the most significant Organ performers in this century. Because I believe I have something new to bring. Also to be the first Organist in a Cathedral (good organs usually are in big churches), to push the people in the church with me looking towards heaven in their prayers by making great music… V: This was his dream. Number 2, it’s obviously the challenge, and it is 2) * Not having Organ or even Classical Music atmosphere around me. V: He lives in Israel. Also * Planning to study Organ and Church Music in Europe (it's very hard and complicated plan) * I need support in social media to get known Love you and Ausra!!! V: What do you think, Ausra, about his dream first of all? A: Well, I’m thinking that he is a very ambitious young man, and I wish him good luck with his dream. V: Do you know any very significant organ performers in this century...maybe in the past century? A: Yes, I know significant in this century and in the last century as well. V: Just name one. Your favorite. A: Well, from which century? V: 20th century. A: 20th century. Well, probably Marcel Dupre comes to my mind. V: This one, right. Do you think Marcel Dupre had this kind of goal or dream, to become one of the most significant organ performers in the 20th century? A: Well, I don’t know. If he wrote a diary maybe if this information is available. But probably not. I guess he just did what he did on a regular basis, because he was really a very hard-working man. And of course he also wanted that people around him, for example his students, would be also very hard working as well. V: Yes. So it usually is the opposite. If you have the dream of becoming famous let’s say, you will not become famous of your work, probably. You could become famous of your physique, appearance, outlook. It’s possible right, if you do something eccentric with your face or your body. But if you want to be well-known because of your work, as Nabil writes, it has to be the opposite dream. You need to be probably more concerned with building up your skills than to building up your fame. A: True, because without your skills, you won’t be able to be famous. Well and in general, if you want to be famous on social media, then I would say that probably organ is not the best way to get known, because it really takes time and effort, and support of course. And luck, too. Well, look at such person for example as Cameron Carpenter. Well, he graduated from Juilliard if I’m correct. Well, do you know what it means to be accepted to Juilliard and to graduate from it? It means that he had to put a lot of effort and to do a lot of work. And now yes, he’s famous on the social media as well. Could you do that? Well I don’t know. V: And also some people get more luckier than others. You mentioned luck, right, and that’s a big factor actually. For example, I know a person who has only two videos on his YouTube channel, but he has several million of views. Organ music, but just two pieces. And he’s not been active for many years now. Just riding this way for a decade maybe. And probably he’s not even playing organ anymore. Maybe changed direction. But it doesn’t mean that he’s not well known because of those two videos. He was young and talented and got somehow noticed. But that’s luck, that’s not hard work. A: Yes. And you know, I already gave up my dream to become famous, and to have, to even gather 1,000 subscribers on my YouTube channel, because I realized that I’m neither young, nor a man and neither slim. So basically, I don’t have any chances to get famous in an organ world. V: Famous is very relative thing you know. You are famous to me, and you’re famous to people who are listening to this podcast for sure. Even though they might not count as one million subscribers of your YouTube channel. But basically, I think it’s a relative thing. If I gave you advice about YouTube channel, I wouldn’t give you advice to be famous or to reach 1,000 subscribers. No, probably the most important thing will be also just to concentrate on uploading music. Playing, recording, and uploading. The same as for Nabil probably. On a different scale, of course. A: I think the most important thing is not to become famous, but to really enjoy what you are doing. To really like and love what you are doing. Because otherwise, all that daily routine that you, all those hours that you have to spend practicing organ might become really tiresome for you if you will not love enough what you are doing. V: Exactly. If you are doing just for the sake of some lofty goal which might be true for you now, but I don’t know about the future, you might change your mind, then you will not last long. You might last one week, two weeks, maybe a month. And then you get burned out, because the results will not be positive enough to create positive feedback loop. Like for you, right? If you had received more subscribers right away, you would keep going and going and going and uploading new music. But it doesn’t work that way. It’s much slower progress, if you keep counting subscribers. If subscriber count is your metric of success, basically. But I don’t think subscriber count is the metric of success. Success probably means a lot of different things to a lot of different people. A: Yes, and you know as about studies abroad, for example in Europe, I would suggest for Nabil to consider not only Europe but also United States - why not? Sometimes they can offer good scholarships to which you can apply. And if you’re talking about Europe, why not to try for example Germany? I think it has really good ties with Israel. V: Correct, correct. Yes. Well, he writes the last challenge as support on social media. Everybody needs attention, right, and everybody fights for this attention. A: Yes, therefore this competition is really severe. V: And some people get discouraged and give up, close their channels and delete their accounts, change their mind a week later and reopen again. That’s fine, but it’s a negative circle, basically. You won’t win this game by doing this, by playing this game. I think most important thing, as you say Ausra, is just enjoy what you’re doing. And keep sharing your music with others. And if that will work eventually, that’s okay. If it’s not, at least you will have a good plan. A: Sure. Because otherwise you might find out after 10 or 20 years of your life that you actually have wasted it and did things that you even didn’t like it. V: Yeah, for example if you suddenly analyze what’s the most popular type of organ music online right now, and start playing it over and over again, this type of music. Not the same piece, but similar pieces by different composers. And you get popular, right - you might get popular this way. But if you keep doing this for years without love, just for the sake of popularity, as you say, you might get revelation that you wasted your time without actually playing anything that you did like during that time, right? A: Yes. V: Thank you, Nabil. And we hope this was useful to other people who are facing similar challenges and have similar dreams. Please send us more of your questions. We love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice, A: Miracles happen. V: This podcast is supported by Total Organist - the most comprehensive organ training program online. A: It has hundreds of courses, coaching and practice materials for every area of organ playing, thousands of instructional videos and PDF's. You will NOT find more value anywhere else online... V: Total Organist helps you to master any piece, perfect your technique, develop your sight-reading skills, and improvise or compose your own music and much much more… A: Sign up and begin your training today at organduo.lt and click on Total Organist. And of course, you will get the 1st month free too. You can cancel anytime. V: If you like our organ music, you can also support us on Patreon and BMC and get early access to our videos. A: Find out more at patreon.com/secretsoforganplaying and buymeacoffee.com/organduo SOPP532: In recent years I had to give up organ playing in public because of my physical health12/26/2019

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas!

Ausra: And Ausra! V: Let’s start episode 532 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Maureen, and she writes: “Dear Vidas, I am a graduate from the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, London which was for piano playing.. I have never sat any organ exams nor played music for the organ at that level. My foot work was not at such a high standard. In recent years I had to give up playing in public because of my physical health. I have a condition called Fibromyalgia which is a painful and debilitating one. Playing the organ was my first love and made my debut in my hometown when I was only 13 years old. I played at a Sunday evening service in the Protestant Church of Scotland and later asked to deputise for my music teacher who was the church organist. Good organists were scarce as was money so choices had to be made as to the disciplines which would be most beneficial to me. I chose piano, singing and cello. Organ was almost an extension to the piano lessons. I loved playing in Church for all the various Sunday services and for Mass. Hymns were particularly important to me and practised diligently each day before I started my teaching. Voluntaries were also played daily in preparation for services. Funeral music was always being worked on and it was my delight in investing in a variety of suitable music. Weddings over the years have dwindled as many people do not favour the sacrament of holy matrimony as once they did in my teenage years. I can have access to a small organ in the nearby monastery of Pluscarden Abbey, Elgin Moray where there is a healthy community of Benedictine monks. They sing plainchant which I love doing when I attend Sunday Mass there each week. I have no transport to attend daily Mass when I could be staying on to play the organ. The nearest I get to practising an organ is on my own personal Klavinova which I can attempt to mimic a near enough pleasant enough sound for the organ. I would like to think that I was more than competent as a regular organist who accompanied Church services. To put a grade on it would be one for my hands and a different level for my feet I think... Thank you for reading this account.” V: And she continues writing later: “The most important fact which I failed to tell you about was the loss of use in my right hand and arm. My hand wouldn’t open out without pain and tightness in the palm of my hand. Pain went through the whole of my arm constantly for five years! Over time and with acupuncture my hand and arm became pain free. Nothing showed in x-rays and nerve tests. What I still find is a reduced dexterity in my hand. The muscles are strong there was no damage to be found only excruciating pain. I would appreciate your advice on which type of exercise I could do daily. Hanson for piano is my mainstay at present. Thank you, Maureen” V: First of all, I’m not familiar with Hanson, maybe she means Hanon. Could be. A: Could be… V: I don’t know. To summarize her situation, I think she had this Fibromyalgia, and the remaining result is that her muscles are not… the fingers are not fast enough on her right hand. Did you understand the same way? A: Yes, that’s what I understood, too. V: So, right exercises, probably, should be done with more care than left hand exercises. A: That’s right. I would suggest for her to take supplements of vitamin B. It’s crucial for muscles, too, and I think that in order to strengthen those muscles, maybe she needs to strengthen other muscles as well, because everything in our body is connected in between, so I guess the physical exercise in general is a good idea. V: If she has no pain in her knees and legs, maybe she can walk—start walking. A: Yes, and you know, when we actually play on the organ or any other keyboard instrument, we need to think about that not our hand is doing it alone, but actually that we have a long arm, which is connected to our back, and actually that our back is even more important than our hands, because the back supports the entire arm! V: In this case, you mean that the hands are an extension of the back. A: True. V: And we have to play with feeling even the back muscles. A: True, and sometimes if you have a muscle problem in your hand, it might mean that something is wrong in your back. So my suggestion would be probably to do some Pilates. V: Pilates. A: Yes. V: Yes, Pilates would be good. It’s moderate intensity exercise, not to be very dangerous, and see how she feels. A: Because you know, if you will do only manual exercises, playing, let’s say, scales or arpeggios or something, and you will play extremely a lot of them, you might hurt yourself. V: Yes. I think with organ playing at this time, she should be moderate. Take moderation into account and not to extend herself, and maybe take care of her general health issues more carefully, and just slowly build up her technique, not expecting results overnight, or over a week, or over a month. Just her goal has to be, I think, just keep practicing, and stopping, probably, before she gets tired, not to hurt herself—not to feel exhausted—and to rest for a while and then playing some more if she wants. A: Yes, and you know, this Fibromyalgia is sort of a very mysterious disease. I read about it, but I still could not understand it, and I don’t think that doctors can, either. V: Okay, guys, please send us more of your questions; we love helping you grow. And remember: when you practice, A: Miracles happen!

Vidas: Hi guys! This is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 453 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Abraham, and he writes: Good to hear from you Mr Vidas. Is it possible to follow these steps and master any organ composition a week before performance? I just have to clarify this question probably. Abraham wrote an answer to my email when I sent him the video of How to Master Any Organ Composition. After the first day when subscribers come to our community, they get this video and start learning this 10 day mini-course on learning to play any organ composition. So, he probably watched this video, I suspect, and has this question: Is it possible to follow these steps (that I taught probably in this video), and master any organ composition a week before performance? Do you think, Ausra, he means that his performance might be a week from now, and he has just started playing the piece, or learning the piece now? A: Well, I’m not quite sure. What about you? What do you think? V: It’s not clear to me. But if it is, then obviously, it depends upon the skill of your ability. A: And it depends on the piece, too. V: Yes, how difficult it is. How advanced are you in organ playing? How good are you in sight reading, those things. And improvisation probably too, I suspect. And harmony. It all comes together in the final performance. So, in most cases, I would say no, right Ausra? A: Probably yes. V: In most cases, it’s too little time. A: It’s too risky. V: Yes. Remember we always advise people to… A: To be ready, you know, a month ahead of time. V: Now I’m saying two months ahead. Just to keep people from stress, you know? A: But anyway, I think you still get some stress during actual performance. Even if you will get it, I don’t know, three months ahead. But if you will do everything that’s possible that’s in your power, then at least you be, you know, won’t feel guilty if something went wrong. V: Mm hm. And if your performance is a week from today and you are just starting, then it’s probably something wrong with the planning process of the preparation. I mean, you have to prepare well in advance and plan well in advance. A: Yes. I remember our classmate in the Academy of Music, he took the last piece of Max Reger. I don’t remember now exactly which one it was. V: Sonata, I think. A: I think it was… V: One of the two sonatas. A: Yes, one of the two sonatas. And I think he counted pages, and it was what, like 30 pages long? V: Thirty pages, yeah. A: And he, OH, I have a month before the performance, so I’ll just have to learn one page per day, and I’ll be ready! Guess what – he never learned that piece and never performed it. V: He learned maybe five pages or so. A: I know, I know. And he saw that it’s a hopeless business. V: And now he is no longer playing organ, by the way. A: Yeah, but he is building them, so. V: Mm hm. A: That’s good, too. V: So you know, I would say that, imagine if somebody asks you to play a week from today something, then you have to play pieces that you already know well in advance. Maybe you can repeat from your last performance, right, Ausra? A: True. V: A week from today, it’s possible to refresh something that you learned, let’s say a month ago or two months ago. I think it is possible. A: Yes. V: If you learn it in a systematic way. But what happens if somebody asks you to perform a week from today and you don’t have anything ready? A: Well then, you have either to improvise or… V: To say no. A: Yes, to say no. V: Yeah, improvising sometimes it’s easier than playing from the score, but not... A: Not necessarily. V: Not for every person. A: If you have never done it before, then just, you know… V: Yes. Just next time, gather your repertoire ahead of time and you will be more secure, I think, when the time comes. A: I think it’s important for organists to keep, sort of like a master repertoire, of what has to be on your list, some music that fits wedding, some music that fits funeral, some music that fits service, and probably like, what, 10-15 of the most common hymns? V: Good idea, Ausra. This is what they would require for Service Playing Certificate at AGO. And this is, I think, well thought of situation, and the most common things that organists have to play. A: Sure. And then, you know, do what you have to do to refresh these pieces, to keep them alive, let’s say. V: Once in awhile. A: Yes. V: Maybe this much of repertoire and hymns would probably take half an hour to play, I would say, once. But if you do this just like once a month, after learning them thoroughly and mastering, I think you would be prepared to play on a short notice. A: That’s right. V: Okay guys. Thank you for your wonderful questions. We love helping you grow. This was Vidas… A: And Ausra. V: And remember, when you practice… A: Miracles happen.

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

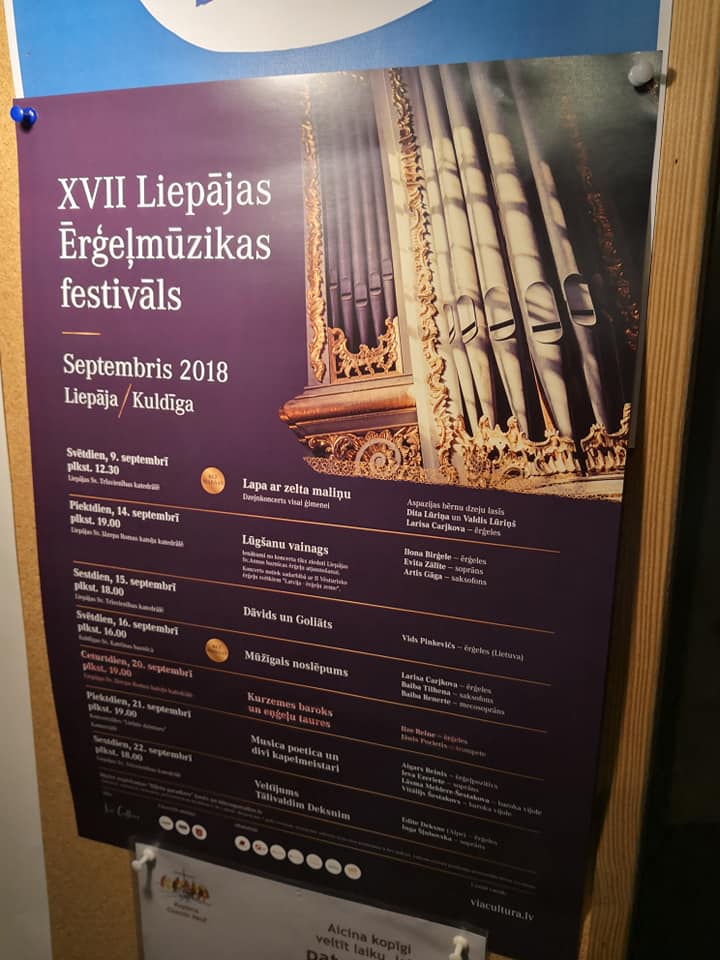

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 321 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Heidi and she writes: “Wow! Vidas Pinkevicius, what an Artist you are! Runs in the family, except your media is painting with music, rather than oils. The music you’ve created and performed here is deeply profound and moving to me. At times, I also noticed that it is so far 'above my comprehension' that I feel a bit confused. In no time, however, the music is telling its story again. The birds singing brought so much joy! I actually wondered for a moment if they were live birds. And then there is the Giant. How I loved hearing the giant come tumbling down. Very deliberately, filled with tension and suspense, slow, getting slower as he descended!! Wow, it was so much fun listening to this. Everything about this piece is wonderful, including the Artist - thank you. Oh, and by the way, the fact that the organ is mechanical totally added to the music’s drama. Beautiful performance by the artist, Vidas. Articulation beyond compare. You deserved a vacation after that.. Whew! I love it. Heidi” V: It seems that Heidi is talking about my performance in Liepaja, Latvia when I recently broke down that organ. A: Yes, nobody will invite you now to perform. V: (laughs.) This was storytelling improvisation about David and Goliath which I recently shared with our listeners too. So what can you say about this feedback because obviously you could tell more things than I. A: Well you know I wasn’t up there together with you so what can I say. Was it rough for you to register during performance? V: I made two recordings. One was rehearsal and another was live performance in front of the audience. This rehearsal which lasted exactly one hour was all the time I had to adjust to the organ so I deliberately limited my practice time on this instrument and wanted to find out how would it feel to give it really live and spontaneous performance on such a big organ with 131 stops. And to my surprise, rehearsal was even more spontaneous I think, maybe because the organ didn’t break somehow. A: Well, do not scare our listeners. You actually didn’t break that organ. The electrical company who was fixing that organ a week maybe before your performance, forgot to add one extra fuse, and since the organ is totally mechanical it needs a lot of power and it didn’t have enough power so that’s why at the end of the recital simply all the power was off. V: Or maybe the organ gave up and said “Oh no, I cannot stand Vidas improvisations, let’s finish this concert earlier.” A: Well I don’t think so. It’s just coincidence. V: You never know what goes inside of this beast. Monster organ really, even without additional side panels it’s already very big but in 1885 I think, Barnim Gruneberg added, enlarged this instrument, made it into a larger instrument than the Riga's Cathedral actually. The famous Walcker organ there and it’s completely mechanical, it only has I think barker machine for the first manual, but no combination action, everything has to be done by hand. So to answer your question, actually, it’s easier to register on that organ than on St. Johns’ organ because the stop handles are shorter. You could move a few of them quickly. A: Well, yes. At St. Johns’ sometimes you get the feeling when you are trying to pull of the organ stop that actually the organ stop might take you into the organ with it. V: Umm-hmm. And I had another improvisation experience when Pope Francis was visiting Vilnius and Lithuania too, so I played in Lukiskes square in conjunction of his prayer at the monument for the victims of genocide. There I had a digital organ, Johannus organ, and that time I didn’t use the stop knobs, I used dynamic buttons, pianissimo, piano, mezzo-piano, mezzo-forte, forte, fortissimo, those kinds of things. A: And I think it worked quite well. V: Yes it was sort of easier for me to just push the button and to see the desired dynamic level but I kind of didn’t feel in control because by pushing the button you give up control. You don’t know exactly what will sound. A: But I think on an occasion like this when you don’t have rehearsals basically, and you are improvising in open space let’s face it, you don’t know how the result will be in a way. V: Yes, you might hear one thing when large speakers are next to you and you don’t know what the audience is hearing 300 meters further. A: And I was listening to it on TV, of course it was broadcast, so I think it sounded fairly well. V: So to go back to Heidi’s comment she started her comment that it runs in the family except my media is painting with music rather than oil. My dad was a painter. A: So do you think it’s largely because of him you are so creative. V: No, I don’t think so. I think we are all creative in one way or another, maybe in different fields maybe, not necessarily in organ playing everybody equally creative. But what I mean, I took from my dad maybe motivation to create because I saw the example but not necessarily the genes. He didn’t transmit his organ playing genes to me because he wasn’t an organist. A: But don’t you think that your parents could understand you better what you are doing because they were artists themselves? V: I hope so, yes. People who create themselves tend to understand other creators better but I could also feel certain limitations when talking to my parents about organ playing. Their knowledge about organ artists was very limited. My dad for example, he could not really differentiate between certain periods of musical composition I believe, so I don’t really know what or how he comprehended organ music. A: Interesting. V: Maybe a little bit differently than a person from the street would but certainly not like an organist. A: Well but still you were lucky you could talk about art in general because what I could talk with my parents was with my mother about blood formula and with my dad about all that building engineering things. V: Which is also creative too. A: Still it’s very far from music and organ playing. V: In order to talk about engineering creatively you would need to know a lot about engineering before you even start this conversation. A: But actually yes, my dad helped me a little bit to understand how the things in the engineering drawings looks like and it helped me in an organ building class that Gene Bedient taught us in Lincoln. V: Listen Ausra, of course your background with your family is different from mine but tell me this, would you say that your creativity over the years diminished or is growing. A: I think it’s growing. V: Why? A: Because I’m living with you. (laughs.) V: No. Because you let it grow I think. That’s all it takes. A: I think simply you stop fearing things, to try things, so it helps. Actually to stop thinking what others will think about you. V: Stop comparing yourself to masters or your peers, your colleagues. Just ignore everybody. Ignore your husband, Ausra. (laughs.) A: I don’t think you would like that. V: Actually I would love it and then I could ignore you. A: Really? V: Yes. A: OK, let’s try it. V: Let’s start ignoring each other. A: How we will do this Podcast then? V: I think our ignorance of each other would last only last until lunch. A: Yes, you always know where the food is coming from. V: Unfortunately. Thank you guys for listening to our silliness. We hope this makes you smile a little, and remember when you practice… A: Miracles happen. Would you enjoy listening to my rehearsal of improvisation recital "David and Goliath" which I played a couple of weeks ago during organ music festival at the Cathedral in Liepaja, Latvia. This is the largest mechanical organ in the world from 1885 with 4 manuals and 131 stops.

Listen to the audio here Let me know what you think.

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 256, of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Jeremy. And he writes: My Boellmann’s Suite Gothique performance at church went alright. Everything felt comfortable before the service, but some wrong notes crept in during the service, particularly in the Minuet. The Priere went really well. One small mistake that is bothering me occurred at the transition into the g minor section. A parishioner did approach me afterwards and thanked me, which was really nice. V: So Ausra, Jeremy is on our team who transcribes fingering and pedaling for us. A: Nice. V. And therefore, he is also a Total Organist student. So, at one point, he wrote that he is going to play entire Boëllmann Suite Gothique. And then I asked him to be sure to give his experience to me so later that I can discuss with you the feedback that he received from people and in general his experience from playing at church. So you see, he played really well, except some small mistake, right? I think he’s talking about mistake in Toccata where the transition into the g minor section is. But this is a wonderful piece to start toccata’s in general, right? A. Yes, I think we talked about it a few times ago. V. So because nobody was listening, let’s talk about it again. And this toccata is particularly fun to play because it has such a comfortable finger position, right? A. That’s true. V. And fun pedal, double pedal octave part at the end. A. Yes, that’s right. That’s very typical of French music in general—that they love to add double pedal at the end of the piece. V. Know what I think? This toccata might be a good model to improvise your own toccatas. A. That’s true. Because I’m not especially fond of this particular toccata, because the theme for myself is not a nice theme. And if I would be a church organist, I would probably not perform it at the church. This toccata is most suited for a horror movie or something like this. V. What makes you think that? A. The theme itself sounds for me like this. V. And what exactly sounds horrible to you. A. Minor key, V. Okay. What else? A. Accompaniment in the hands too. It’s quite scary. V. Exactly. And then there is one more thing that I’m thinking about. Do you know what it is? In the pedals. A. Yes, I know what you mean. I don’t know how to express it. V. In the middle of this theme there is a G flat. A. I know, that G flat, yes. V. Diminished fifth, and it sounds especially—I wouldn’t say ugly but it sounds strange. A. Well, so I think it’s a nice piece, but not for church service maybe. V. Mmm-hmm. What if somebody played it in a major key? A. Try it and see how you like it. V. (Laughs). Maybe it would be better. So Jeremy, I don’t know if Jeremy likes to transpose but that one might be a nice exercise in transposition, to transpose this toccata into the key that is maybe a related to C minor, maybe E flat Major. A. Anyway this toccata has a strong character. V. Yes. Once you hear it you will not forget it. A. That’s right. V. So, but of course the Prière; the Prière is most, one of the few beautiful pieces. Suitable for church too. A. That’s right. It’s very nice. Very very nice. V. Is it more suitable for Communion or Offertory? A. I think it could work both ways. V. Depending on how much time you have, right? A. That’s right. V. What makes the Prière so beautiful, in your opinion, Ausra? A. Well, nice melody, beautiful harmony, nice soft character. V. Legato touch. A. That’s right but most of the things in Boëllmann should be played legato because that’s his style. V. What about registration? Do you like the strings? A. Yes. That’s true. V. What kind of an organ would suit best, except of course, organs in Paris? A. So why I cannot choose French symphonic instruments for this piece? V. Because the majority of people don’t live in Paris. A. Well, but they still can organ with string stops. V. Strings, right? A. That’s right. V. Okay. What if you don’t have strings or even maybe one string, like you’re playing Neo Baroque organ for example? A. Well then you have to replace strings with flutes. V. Mmm-hmm. The more foundation stops, the better. A. That’s right. V. The more stops with the same pitch level, the better. A. Yes. So if you have only one string, add couple of flutes to that string, and it should work just fine. V. Couple the manuals. A. Yes, that’s (a) possibility too. V. We have created the fingering both the Prière and the Toccata too. Not yet for the Menuet. Menuet, do you like menuet? A. Yes, but I like Prière more. What about you? V. I don’t particularly. I think Menuet actually sounds better than the introduction of the Suite Gothique. Introduction Choral, it’s called. In the beginning, sort of Menuet, is just the regular chordal piece, but then it grows into something more with more of the elegant Scherzo texture. It becomes really nice. So Ausra, do you have any recommendations for Jeremy, if he wanted to play the next French symphonic work by, I don’t know, 19th Century or 20th Century composers? A. Well there are so much Romantic or Modern repertoire, if we are talking about 19th Century not 20th Century French music, so he could choose any of them. V. Talking about a difficulty level, right? You have so many difficult pieces. And Toccata, for example, is rather easy to play, right? What would be the next step? A. Well, if he also wants nice, French, and not too hard music, he might consider Langlais Suite Médiévale—Medieval Suite. V. Mmm-hmm. A. I think this is also nice setting of the pieces. V. I haven’t thought about it. Good suggestion. And it’s a 20th Century modal language. Maybe Jeremy is not used to that, so that would be a good introduction. A. Well, try it and see if you like it. V. Yes. A. If you will not like it, you may go back to an earlier age, let’s say try some Widor. V. Widor. Exactly. Like Vierne Symphony would be too difficult, I think. A. Yes, it’s too difficult yet. V. Unless, he played some of the movements from the Fantastic pieces. A. Oh yes! You could find some easier, more even in the symphonies, but if you would compare Vierne Symphony with Boëllmann Toccata, then of course the difference would be too great. V. Dubois and Gigout Toccata’s would be rather doable. A. Yes and we talked them a few times. V. Mmm-hmm. Okay guys. Thank you so much for listening. We hope this was useful to you to get general ideas (for) what you can do after you master Boëllmann Suite Gothique, and what makes it suitable or not so suitable for church services. Please send us more of your questions. We love helping you grow. This was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: And remember, when you practice,,, A: Miracles happen!

This blog/podcast is supported by Total Organist - the most comprehensive organ training online. It has hundreds of courses, coaching and practice materials for every area of organ playing, thousands of instructional videos and PDF's. You will NOT find more value anywhere else online...

Total Organist helps you to master any piece, perfect your technique, develop your sight-reading skills, and improvise or compose your own music and much much more... Sign up and begin your training today. And of course, you will get the 1st month free too. You can cancel anytime. Check it out here Here's what one of our students is saying: Thank you very much Vidas! My biggest challenge is still to be patient and not rush ahead in a piece before I have mastered it bit by bit. I know this is a very bad habit and the reason why I never can play without making mistakes. I am trying to find the discipline! Practising just one piece does get a bit boring so in addition to BWV 639 I have now also started working on BWV 731. I have practised this in the past but with different fingering, I am now relearning it with yours. Best regards, Jur Would you like to receive the same or even better results that Jur is getting? If so, join 80+ other Total Organist students here. Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 246 of Ask Vidas and Ausra podcast. This question was sent by Michael. He writes: Hi Vidas, I had private lessons with Michael Schneider in the 70s and 80s for 13 years - I am very satisfied with my playing technique and don’t have serious difficulties with the literature. I had a 30 years break - settling in my job and having a family with 2 kids. In 2010 I discovered the Hauptwerk software and bought a three manual console and several sample sets. I took up practicing again and brushed up most of my repertoire. A few pieces are still open: JSB Toccata in F, P&F in E flat and in E minor, Dupré op. 7 - but this is only a question of time, not of difficulties. At present I am studying Carillon de Westminster - it is almost finished. My challenge is to keep all these pieces warm, so that I can play them without too much preparation time. If you are interested in my performances, go to contrebombarde.com and search for bartfloete, my musical nickname. All the best for you and Ausra and thanks again. Best regards Michael V: So, Michael can play quite a difficult repertoire, Ausra, right? A: Actually very difficult. All the pieces that he named are the top difficulty level. V: Dupré Opus 7, those Three Preludes and Fugues in G minor I believe, A: It’s B major, then F minor, then finally G minor. V: G minor. So difficult to play, especially G minor, I think. A: Yes, and I played B major. It’s challenging, too! Fugue, especially. And we have heard some not very successful performances of these three pieces by quite famous American organists, so, that’s quite a challenge. V: Yes, and Toccata in F major by Bach—it could be a very long and tedious piece to play, if you are not careful, if you are not playing musically. A: And those cadences in the Toccata section, I think are the hardest thing in that piece. V: And of course, E flat major Prelude and Fugue, that’s probably a pinnacle of Bach’s writing, in general, for organ. So, you would probably enjoy, tremendously well, just practicing this piece, not only performing it. A: True, and then, he mentions the Prelude and Fugue in E minor, and I believe he means, probably, “The Wedge,” V: “The Wedge,” yeah. A: Yeah, which is, I think, one of the hardest pieces for organ that Bach wrote. V: Even harder than E flat major Prelude. A: I would say so, yes. V: Because of the fugue, probably. A: True. V: Running passages and virtuoso texture. A: True, and it’s also long, as is the E flat major. V: So, his challenge is to keep all these pieces warm, and be able to play them without too much preparation time. That’s very simple, right, Ausra, because, A: Yeah… he has to play them. V: Play them all the time, and let’s say he has a repertoire of about one hour, right? Toccata and Fugue in F major, that’s 15 minutes, E flat major, another 15 minutes, A: Well, perhaps 17 V: A little more, then E minor, so 3/4 of an hour more, probably, and Dupré Opus 7, so that’s more than an hour, I think. A: Oh, it’s much more than an hour. V: Mhm, because Dupré 3 Preludes and Fugues is more than a half an hour already. A: Well, I would say probably more, because that F minor, the middle one is in a slower tempo. V: And Carillon of Westminster, by Vierne, so that would conclude his hour of Bach and Vierne, and Dupré, in addition, a half an hour set… A: Well, that’s like two recitals, I would say... V: Almost two recitals. A: Almost two recitals, yes. V: One and a half, at least. So if he has to keep these pieces warm, he has to play them, not necessarily every day all things, but to have a plan to play them regularly. A: Well, let’s say you choose two pieces for each day that you will work up on and repeat on, and the next day you will do another two pieces and just keep going like that, and keep rotating. V: Yes, Bach F major, E flat major, and then E minor—three. Dupré, three more, that’s six, and seven, Vierne. So, basically yes, in three days, he can do brush up. A: Yes, and you know, it doesn’t matter, there is no magic trick that you learn pieces and you will be able to play them after ten years without practicing them. No, you need to keep practicing and to keep refreshing them. Of course, it always depends on how well you learned them for the first time. For example, did you play them with the same fingering all the time? Because this makes things easier for you to repeat and to keep it in good shape. V: Let’s suggest to Michael to memorize. Would that be helpful in the long run? A: Yes and no. Don’t you think it’s harder to keep things in memory than to read it from a score? V: Yes, he doesn’t have to perform from memory, he just has to learn it inside out. And then, when it comes time to perform from the score, it would be easier. A: Yes, true, but you can do that if you have a lot of time. So, it depends on your schedule. And, for example, for some people, when you learn to play something from memory, it’s very hard to go back and to play it from the score. You need to keep that in mind, too. Not for everybody, but for some, yes. V: I see. Interesting. What else could Michael do? What would you do in Michael’s shoes if you had plenty of time and would like to learn those pieces and keep them warm in your repertoire, in addition to practicing them regularly, maybe twice a week. A: Well, what helps me, actually, is to play my repertoire in a slow tempo. This sort of keeps everything well under my fingers and then I can play pieces for a very long time without ruining them. V: If you play them in the concert tempo, you can get carried away and don’t notice details and ruin the performance. A: True. Yes, because things might get muddy when you practice all the time in a fast tempo. Of course, people think, “Oh, if I play it fast, then I can play more pieces,” and that’s what we do, but I don’t think that’s a good way to do it. V: You have to think long term. What would today’s practice mean for you three months later? A: And I think it especially applies for practicing Bach’s works, because they are such polyphonically complex pieces, and you can miss many important details while practicing in the fast tempo all the time. V: And one last thing. Obviously, if you are so good with those pieces, like Michael is, probably, then it would be wonderful to go out and play in public. Don’t you think? A: Of course, and I think that’s what he does. He has his page on YouTube. V: But that’s in public… he records himself and publishes, but I mean in live performance, maybe in a church setting, maybe in a concert settings, even. Go out in his area, make friends with local organists, and arrange recitals! A: Yes, and another suggestion for him would be that since all the pieces that he mentions, he played them a long time ago, and now he is repeating them. So maybe it’s time to learn something new that he hadn’t played before. V: Ah, I see. Yes, if you only repeat your repertoire from the past, you are not really advancing. Right? A: Well, you are advancing, but you are not expanding your repertoire. V: You are advancing, but not expanding your musical horizons. So that is great final advice, Ausra. A: And he studied with Mike Schneider, as he mentions in his letter, and sometimes we think that we will not be able to learn new pieces without a mentor or a teacher. V: Which is not true… A: Which is not true. Because, if you have already learned so much hard repertoire, I’m sure you can do something on your own, too. V: And teach others, if you like. Thank you guys, this was Vidas, A: And Ausra, V: Please send us more of your questions. We love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice, A: Miracles happen. #AskVidasAndAusra 129: There Is A Great And Profound Joy In Practicing And Performing on the Organ12/22/2017 Vidas: Let’s start Episode 129 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. Listen to the audio version here. This question was sent by Helene, and she writes that her challenge is not keeping up with her daily practicing. She writes:

“I have talents in other ways in that I write fiction and non-fiction; I play other instruments, too. However, there is a great and profound joy in practicing and performing on the organ which is unparalleled.” Ausra, do you have other hobbies/interests/talents besides organ? Ausra: Yes, I do have some. Vidas: So it’s a perfectly normal thing-- Ausra: Of course it’s normal, yes. Vidas: --To have many interests instead of just one. Ausra: That’s right. Vidas: What would happen if a person would have just one passion, one single focus? Ausra: I think he would become very good in that area in which he concentrates. That’s my opinion. Vidas: Wouldn’t that be like...a limit for that person’s personality growth? Ausra: Hmm… Vidas: You know what I mean? Ausra: Yes, I know what you mean; but people are different, so you cannot judge for everybody. And you cannot measure everybody by the same scale. Vidas: For example, I also have some hobbies besides playing the organ (playing the organ is not my hobby anymore, of course); but there is a downside to it, of course: it all takes up energy and time. Ausra: Yes. And actually, I see a conflict in this question itself: because she writes that she is not practicing daily, and then she’s telling that it gives her profound joy, practicing and performing the organ. So...I sort of see a conflict in this. And she plays other instruments, as well. Vidas: Maybe she should choose what is more important to her. Ausra: Yes, because, I mean, if she really finds joy and happiness in practicing and performing organ, then that’s what she should do. And you know, you will not be a virtuoso in any instrument that you play; I think it’s impossible-- Vidas: You mean, in every instrument. Ausra: In every instrument, yes. Especially if they’re not all, like, keyboard instruments. I would say you could play excellent on harpsichord and organ, or organ and piano; it’s harder, but still possible. But...not like, probably, violin and organ. Or flute and organ. Vidas: Or flute, violin, and organ! Ausra: I know--still one of the instruments will be the leading instrument, for you. Vidas: Mhmm. It seems to me that she enjoys writing very much, right? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: She’s writing stories--made-up stories and nonfiction. So that might be another way to express her creativity. Music and writing are not in conflict, I think--they supplement each other, right? Like other instruments and organ may be in conflict, but writing and organ are not necessarily in conflict. Ausra: Yes, this is true. Vidas: How many hobbies can a person have and still manage them successfully, do you think? Ausra: I don’t know--2, 3 maybe? Vidas: 2-3? Let’s say not hobbies, but activities. It might be other things-- Ausra: Well, you know, it’s like talking about nothing--it depends on how much time you spend at work everyday, how big your family is, how many domestic responsibilities you have...All these things, you know--some people are so busy that they cannot have even one single hobby. For example, like, I’m working late at school everyday. So, it’s a different story with you--maybe you should tell about your hobbies. Vidas: I’ve heard--I’ve read, actually--a story by...Warren Buffett, I think...yeah, the famous investor. And he says that you should write down a list of 25 things you want to do in life, in order from the most important one from the least important one. But all these things are important to you: like playing, like writing, like maybe drawing for some people, like other things. And some people really have 25 things on their plate. And then, he says, circle the top 5, and cross out the rest of them--like 20 things--and never look at them again. These are still important things to you, but life is too short. For myself, I have too many interests, too, and I have to limit myself, too. And I find that 5 things in my day, I can still fit in; and practice, every day, 5 different things, perhaps. Like let’s say, of course, playing the organ--repertoire, right? Maybe like...of course, improvising; like composing, number 3; and then would be writing, of course; and I like drawing, too. So those 5 things are still manageable. But other things I have to forget about, I think. What about you, Ausra? Do you agree with this? Ausra: Well, yes. I would be very happy if I could do 5 things a day! My teaching schedule is so busy that it gives me no time for anything else. There are days when I can hardly practice, and I’m very happy if I can read for like 15 minutes before bedtime! When you teach like 7, 8, 9 hours a day, what else can you do? It’s exhausting! Vidas: Yeah. Of course, I didn’t say reading; reading, of course, is important. I didn’t count that. So yes, Helene and others who have many interests and hobbies--and love to play the organ besides that--sometimes need to figure out a way of letting things rest awhile, and see if they’re still important, right? Maybe take a break of 5 weeks or a month without doing that activity, and see if you miss it. Right? And if you do, then maybe you’ll see it’s important, and maybe it has to go up in your priorities list. What do you think about that, Ausra? Ausra: Well, definitely, yes. Vidas: Okay guys, please send us more of your questions; we love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice… Ausra: Miracles happen.

Vidas: Let’s start Episode 67 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. And today’s question was sent by Vince. He writes:

“Dear Vidas and Ausra: When I am playing hymns or a classical piece with 4 parts, sometimes a mistake happens where I can not tell which voice has the mistake. If performing, and not able to stop and figure out where the mistake is, the error may carry over to subsequent notes in that part because I don't know WHERE to make the correction. I'm not tone deaf, but at times the mistake totally eludes me, even so far as, the mistake is in the pedal but it sounds like it is in the soprano! Any advice on how to deal with this? Please don't say "just play perfectly!" :-) Perhaps ear training, but what method? Thank you very much. I enjoyed the interview with Kae Hannah Matsuda.” So, it’s wonderful question, right? I’m very glad he liked this interview with Kae, who helps us to transcribe those podcasts and make text versions available to you. Without her help, this would not be possible, so thank you so much, Kae. And Ausra, Vince is having a problem with detecting mistakes, right? Ausra: Yes. So, as he told himself, I think that ear training is the best solution to solve his problem. Because you have to learn to hear each voice that you’re playing, and it doesn’t matter how many voices you are playing at a time--you have to hear them all. And I would have a couple suggestions for him how to do it. First of all, he has to learn to sing each line of his hymn. If it’s four voices, he has to learn to sing them all, and to know them all by heart. Vidas: That’s very great advice, Ausra. All the main professors we’ve worked with recommend this technique, too. And obviously, this helps. Every time you discover a polyphonic piece with independent voice lines, you have to simply listen to inner voices especially; and there is no other way to do that at first, than to actually sing it. Ausra: Yes, and when I teach solfége we sing four-part exercises; and the main technique is, you know, that the student comes to the piano; and for example, I’m telling him or her, “Sing me tenor”--it means that he or she will sing the tenor line, and will play the other three parts together. Vidas: Aha, so tenor will be silent. Ausra: Yes, tenor will be silent--from the keyboard; but he or she will sing it. That’s an excellent technique, it develops your ear very well. Vidas: How do your students react to this at first? Is it frustrating for them? Ausra: Yes, it is frustrating for them. Not so much for choir conductors; but for other majors, yes. And everybody wants to sing the soprano line, but I never ask to sing the soprano line, because that’s the easiest part! And basses, not so bad; but alto and tenor are the hardest voices to sing. But they are very useful for your ear training. Vidas: But they don’t start with four-part textures, do they? Ausra: Yes, if it’s hard for you to do that, you have probably to just take a bicinium. I mean, two voices--a two-voice piece. Play one, and sing another one. Vidas: I would even think that Vince should start with a single part, a single voice. Just imagine it’s a counterpoint exercise, just like organ playing; so ear training is sort of also an art, and a skill you should develop equally well over time. And with organ, you could start with one single line. So why don’t you start with one single line when you sing those melodies? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: From your own piece. Or a hymn. You don’t need to actually get a special ear training book for that. Ausra: Well, a hymnal is an excellent source of things--you can do exercises from any of the hymns. Vidas: Yeah, absolutely. The voices are sort of independent, but not too independent. Ausra: You can take, for example, a four-part hymn, and just omit the middle voice, tenor or alto, and do soprano and bass. If it’s very hard for you, just play bass and try to sing soprano (melody), which is well-known to you; and then, you know, play soprano and sing bass. And then maybe,you know, later, when you feel comfortable with those two voices, you will add two more voices. But it will take time; these things take time, but it’s worth doing it. Vidas: I have just had an idea now, like lightning struck into my mind, that a similar course designed specifically for organists who play hymns to develop their ear training, would be excellent and very, very helpful, right? If we could devise such a training program, then over time, people could really develop a much better sense of pitch, discovering their mistakes, expanding their abilities to understand the pieces that they’re playing, right? Ausra: Yes. Because if you can sing correctly, I don’t think it will be a problem for you to hear if you are playing it correctly or not. Vidas: Mhmm. Right now, as we’re recording this, I only had prepared a melodic dictation course, basically for one melodic line. And that’s not enough, right? You have to actively sing, learn to sing those melodies--and in combination of melodies up to four parts, over time. Right? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: So guys, maybe we will try to figure something out and systematically develop such a training, so that you could simply jump in and get started with the materials; and over time, develop your sense of pitch--just like we would teach our students at school, National Čiurlionis Arts School in Vilnius, which is extremely well-equipped with theory, with music, harmony training...and things like that, for musicians. Please let us know if such a course would be helpful to you or not. Wonderful! Thanks, guys, this was Vidas. Ausra: And Ausra. Vidas: And remember, when you practice… Ausra: Miracles happen. |

DON'T MISS A THING! FREE UPDATES BY EMAIL.Thank you!You have successfully joined our subscriber list.  Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas

Authors

Drs. Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene Organists of Vilnius University , creators of Secrets of Organ Playing. Our Hauptwerk Setup:

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

This site participates in the Amazon, Thomann and other affiliate programs, the proceeds of which keep it free for anyone to read.

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed