SOPP668: I would like to master a variety of organ music to be able to give a performance11/10/2021

Vidas: Hello and welcome to Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast!

Ausra: This is a show dedicated to helping you become a better organist. Vidas: We’re your hosts Vidas Pinkevicius... Ausra: ...and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene. Vidas: We have over 25 years of experience of playing the organ Ausra: ...and we’ve been teaching thousands of organists online from 89 countries since 2011. Vidas: So now let’s jump in and get started with the podcast for today. Ausra: We hope you’ll enjoy it! Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas, Ausra: And Ausra, Vidas: Let’s start episode 668 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Mike, and he writes: “I would like to master a variety of organ music to be able to give a performance. The most important hurdles to overcome are:

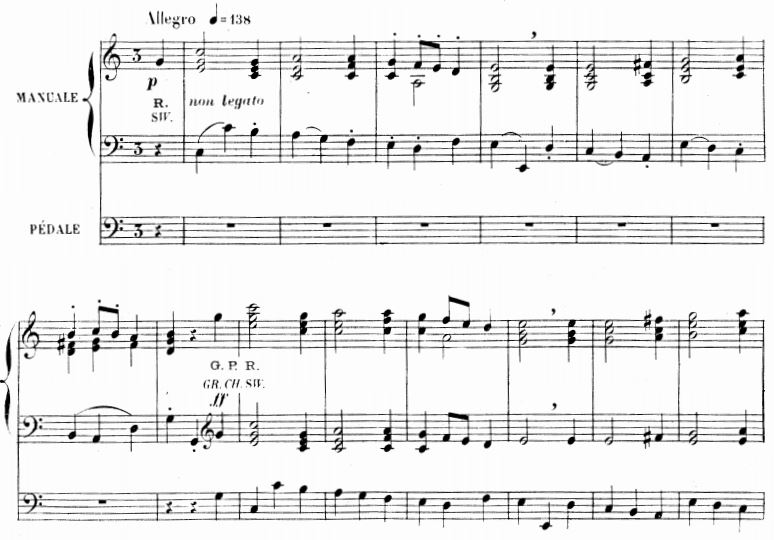

Many of your podcasts and notes are extremely helpful. Thank you for providing them.” Vidas: So let’s unpack this; okay? The first hurdle that Mike is having is being able to work on a consistent fingering to make passages flow smoothly. Ausra: Well, in order to be consistent with your fingering, you have to write fingering down, and then to practice them in the exact order, because if you won’t do that and you will play the same passages every time with a different fingering, it will slow down your improvement. What do you think, Vidas? Vidas: Is it even possible to discover the right fingering on your own? Ausra: Well, if you have experience, then yes. If you are just a beginner, then probably not. Vidas: Mhmm, then we could probably recommend our practice scores with fingering and pedaling written in. Ausra: Yes, sure, because we have already quite a large amount of organ pieces with fingering and pedaling. Vidas: Yeah, in many styles. In articulate legato style for early music, and in legato style for Romantic music. Right? Ausra: Yes, that’s right. Vidas: Okay, the second challenge that Mike needs to overcome is interpretation of music, registration. Ausra: Well, in order to be able to do the right interpretation and registration, of course, you need to know about the style that you are playing, the composer that you are playing, and of course, about organ in general, and you need to be able to choose the right repertoire for the right instrument. Because even if you will play the… let’s say the Baroque piece with good articulation but you will play it on the, let’s say, Romantic instrument, it might not work, so, everything has its own rules. What do you say about it, Vidas? Vidas: It’s kind of difficult to give advice generally without knowing what he is specifically playing. Right, Ausra? Ausra: Yes! Yes! Vidas: What piece he is struggling with right now, what piece needs a registration, for example. But in general, yes, you are right, because not every instrument can accommodate every type of music. I mean, you could play anything on a keyboard with pedals which has enough pedals and keys. Right? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: You could! Ausra: And if you have an eclectic instrument you could probably play most of the repertoire, but not everything still would work for it. Vidas: That’s why a lot of organ music sounds dull and boring on eclectic instruments—a lot of early music. Nowadays, of course, this can be adjusted, because a lot of people have virtual organs at their home like Hauptwerk or GrandOrgue, so they can really choose samples that are carefully fitted for a specific piece or type of music. And then, even pieces which would sound uninteresting on a generic instrument are quite colorful suddenly on the specific kind of instrument that it was designed for. Ausra: Yes, but you know, not everybody has the Hauptwerk or GrandOrgue or whatever, this kind or type of instrument at home, and we are mostly talking about real instruments in a real environment. But basically, an eclectic instrument is good because you can play a lot of things on it, but in some way, it sounds sort of boring because it’s like an equal temperament, you know, you can play in all the keys, but they all sound the same. Vidas: Exactly. If a person doesn’t feel the difference when I’m playing C or C# major chord, so then I could simply play the same piece up a half step and nobody would tell the difference. Right? Except maybe for some perfect pitch people. But that’s not the big difference. The difference is in character if each note is a little bit from each other sometimes in those unequal tunings. Ausra: And the same with the repertoire. Vidas: Right? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: So the third challenge that Mike has to overcome is developing and knowing how to make a piece “artistically my own instead of just playing notes.” What he means by this is maybe…. We could talk a little bit about our own practice process. How do you transition from sight-reading to real performance—complete performance for a recording, let’s say. What’s happening in your mind, Ausra? Ausra: Well actually you need to be really well familiar with your piece that you’re working on, because you cannot feel the right music and be artistically sufficient or to make this music yourself if you are not good technically at it and if you are still struggling, let’s say, with some spots on the piece. It means that you really need to be advanced with the particular piece that you are working on. Another thing, you really need to listen to other people play, and not only to organ music, in general you need to listen to other people performing, because, you know, when you are really deep into music in general, probably such questions wouldn’t even arise, because let’s say I play a piece and I see it’s structure, I know where I have to slow down, where I have to, let’s say, mark something, or you know, to do an accelerando, or to change registration or to do whatever. It just becomes natural. Vidas: That’s because you know the structure. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: Or because you listen to other people. Ausra: Well, it helps. Or do you think these two things are contradictory? Vidas: No, I think the more you listen to performances of other people on other instruments, perhaps, or even your own instrument, like organ, the broader you have those experiences and musical horizon. Right? And the deeper connections you can make between separate things on the sheet of music is notes start to speak to you, how they are presented. If you don’t have any experience, like a beginner, then you are like a blank sheet of paper. Right, Ausra? Ausra: Because yes, I once had a student and we were working on the “Little Prelude in F Major” by J. S. Bach, which is actually probably not a Bach, as we know now, but probably Krebs, but anyway, we were working on this piece and she would just keep playing like the metronome all the time and do the same things all the time, and I wanted her to show how the structure is made, and I actually marked everything in her score: where she has to slow down, which chord she has to hold longer, and all that kind of stuff. Basically I worked as a movie director or something. But still it didn’t ring a bell at all, and she still played like dull, measure by measure, note by note, and did nothing of what I was saying. Maybe if she would listen to herself, to her recording, maybe then she would realize how dull she is playing! Maybe that would have changed her attitude and her playing style, but I think that comes from general unmusicality, and that’s why I think the more you listen to the music in general, the better you will become with it, because the deeper your understanding about music in general will become. Vidas: That’s why it’s so beneficial to go to concerts, not only to listen to recordings and videos, but to go to a real recital or a concert in a concert hall or a church, because when you go someplace, you are more inclined, actually, to focus than at home, because you made an effort to go there, and you want to take out as much as possible from that experience. Right, Ausra? Ausra: Yes! And actually another helpful thing would be to sing your music—actually to sing each line—because it’s often the case that we can play unmusically, but we cannot sing unmusically. Somehow if you are playing you can just drop the end of a phrase not listening to it. But if you are singing, that usually don’t happen. Vidas: And that’s why when I see a person play unmusically and ask to sing it, they never can sing. Never ever in my teaching experience, you know, that never happens. Ausra: Because singing is so closely related to to breathing and breathing is so important because that leads to the right phrasing, so I think it’s really, really important to sing what you are playing. Vidas: Then you can think about the right meter and pulse, and keep the steady rhythms. Right? But that’s because you hear yourself. Ausra: Yes, that’s right. And another thing, often the instrument can teach you, also, how to play, and it can show you if you are taking a right tempo, if you are playing with the right fingering, because I’m talking especially about historical instruments, because again, they can teach you a lot about phrasing, about articulation. Vidas: Right. Another last, probably, recommendation would be, for example, if you like some musician, some organist, and you find his recordings or her recordings, I think it’s wise to study them all from the beginning until the end, and then not only his recordings or her recordings, but find out who it was—that person, that organist, lets say—and start listening to other people’s music as well, and that’s how you broaden your horizons and general musicianship as well. Ausra: That’s very true. Vidas: Right? You are not alone in this musical universe. You have to go out and make connections. Ausra: Sure. Vidas: Thank you guys for listening to this conversation. We hope this was useful to you. Please send us more of your questions; we love helping you grow. And remember; when you practice, Ausra: Miracles happen! V: This podcast is supported by Total Organist - the most comprehensive organ training program online. A: It has hundreds of courses, coaching and practice materials for every area of organ playing, thousands of instructional videos and PDF's. You will NOT find more value anywhere else online... V: Total Organist helps you to master any piece, perfect your technique, develop your sight-reading skills, and improvise or compose your own music and much much more… A: Sign up and begin your training today at organduo.lt and click on Total Organist. And of course, you will get the 1st month free too. You can cancel anytime. V: If you like our organ music, you can also support us on Buy Me a Coffee platform and get early access: A: Find out more at https://buymeacoffee.com/organduo

Comments

SOPP564: Important to me is to take songs which are outside of the Church or Classic repertoire2/15/2020

Vidas: Hi, guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra V: Let’s start episode 564, of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Jason. And he writes: Hello Vidas, Thank you for your email. My dreams are to be truly expressive in whatever I play. I want to do my own arrangements and improvisations to pieces. Important to me is to take songs which are outside of the Church or Classic repertoire. With these songs I would create interesting organ pieces with real musical depth, I’m talking about arranging music like Jimi Hendrix—Voodoo Child, David Bowie—life on Mars there are so many. Sticking with more standard pieces then new stuff like Hans Zimmer—Interstellar pieces would be great. But above all the knowledge and ability to arrange and play modern pieces. What is holding me back is my brain over complicating music theory. Thank you Jason V: Music theory is always a drag, right? A: Yes. V: Can you create arrangements and improvisations without knowing music theory? A: I don’t know, unless you are a genius, probably. V: Yeah, you can do intuitive things without knowing what you are doing, but then you cannot explain to others. A: That’s right. So I guess that knowing music theory is a crucial thing. V: Mmm-hmm. Of course, if you always can explain what you’re doing, it’s not always that interesting, right? A: True. V: It has to be some mystery. A: I know, but I think in nowadays there are no problems in creating sort of transcriptions. Because basically what he is talking about, Jason, it’s basically transcription. And I think that many of music software nowadays can do that for him. Or at least help to do it. V: Well, yes. For example, let’s take a song by David Bowie or Jimi Hendrix, right? Or Hans Zimmer. If he can get a hold of the score, like original score imitation, and then put it into Sibelius or Finale, any other software that does arrangements automatically, and with the press of a button he can specify how many voices does he want to have in each hand, how many stave mutations, if its suitable with pedals or without pedals, things like that, and he can specify the style, actually, and that would be produced automatically. I’m not sure if that’s the best result, but for starters it’s no-brainer. A: And I’m not really sure that’s a legal thing, because all these authors that Jason mentions in his letter, I guess they are still alive, still living, and I don’t know what about copyrights, and do you have a right to do arrangements with their music. V: Yeah. Jimi Hendrix and David Bowie, they are not with us anymore, but obviously copyright holds, uh… A: Yes, because I think it was hold like seventy-five years after death. V: In some countries seventy-five, in some fifty, after death. A: But still, you know… V: But of course copyrights can be renewed after that, so you have to be really careful. And license your arrangement. You can purchase licensing actually, and then do this legally. A: Sure. V: Can you do this for your own enjoyment, if you don’t share the music anywhere, just for your private use, legally? A: I think so. V: Do you think so? A: If it’s for yourself, yes. V: I am not so sure. I’m not a copyright lawyer, so don’t site me on this. Better to consult copyright lawyer on this, even for private use, if you’re creating like a cover song as they call it, if you create your own arrangement of the original copyrighted popular music song. That’s really complicated and guarded very, very fiercely by copyright holders. A: Yeah. And you know while talking about all this kind of music that Jason mentions, I’m not sure that organ is the best instrument for this music to be played on. V: Yes, for us. A: Some if it might work but some of it might just sound ridiculous. V: You know this is our taste and people have other tastes, you know, and what works for us not necessarily works for Jason and vice-versa. People enjoy for, example, listening to Queen’s Rhapsody in Blue. Not in blue... A: (Laughs). Bohemian Rhapsody. V: (Laughs). Yes. Who created Rhapsody in Blue? Gershwin. A: That’s right. V: Yes. Bohemian Rhapsody on the organ. Some people enjoy that. That’s not what my taste prefers though, but I don’t judge other people, not at this point in my life at least. What about you, Ausra? A: Me too! V: Freedom of expression should be available to all on earth, whatever they want to do. A: But let’s say that if Jason wants to do everything from the scratch by himself and he definitely needs to know music theory. There is no way to escape that. V: Well, that’s a good point, yeah. Something to think about if you’re serious arrangement and improvising based on those arrangements, you have to know what you’re doing and music theory helps to see the ideas behind music that composer or songwriter, in this case, have put into the piece. A: And you know, I guess because we are talking about popular music now, I think we have a little of their version of music theory too. So basically what applies to the common period may not be applied to the popular music. V: That’s right. A: So this is all another world. V: Yeah. Yeah, you have to do many experiments and do trial and error before you find what works and what doesn’t. That’s the best teacher, I think. A: Yes. V: Thank you guys. This was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: Please send us more of your questions. We love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice… A: Miracles happen!

Welcome to Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast 562!

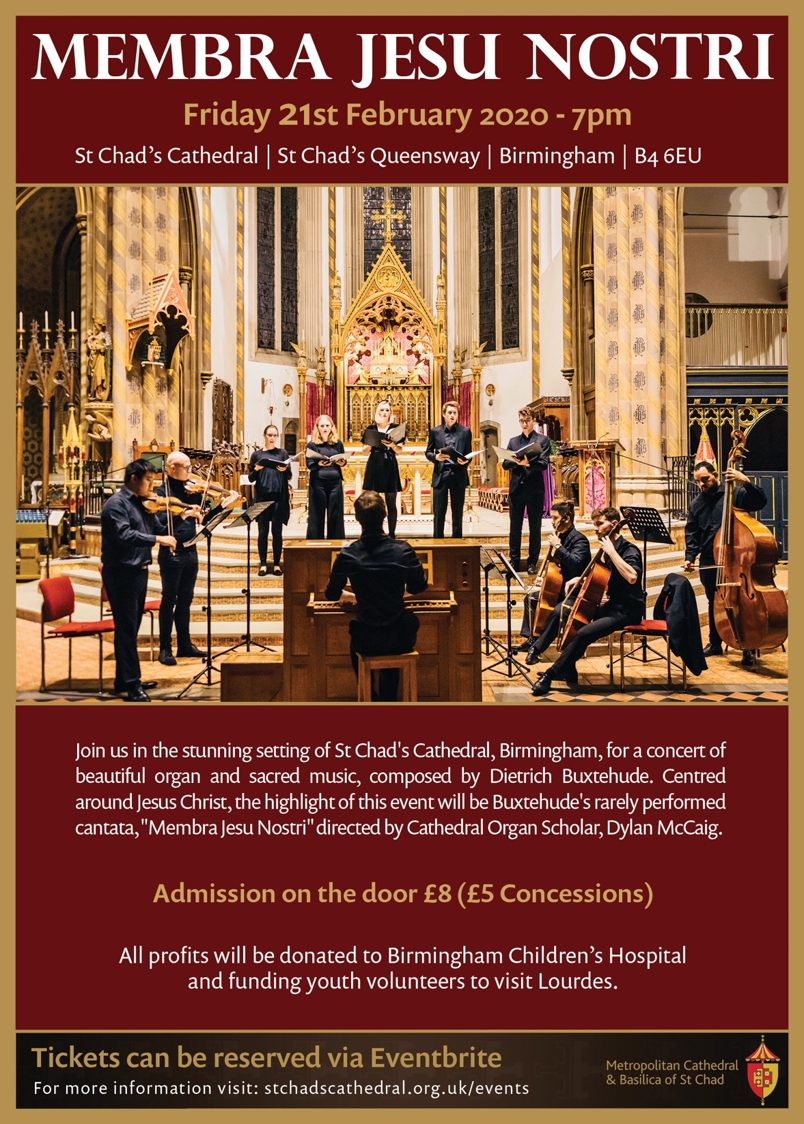

Today's guest is an English organist Dylan McCaig. Dylan is a former Head Chorister of the Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral and achieved his RSCM Gold Award at the age of 11. He studied at St. Edward’s College and was appointed Junior Organ Scholar at the Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral during his time in Sixth Form. Dylan has achieved his Grade 8 Piano and Organ with Distinction. He is currently in his final year studying Music at the Royal Birmingham Conservatoire on a scholarship, specialising in the Organ, under the tutelage of Daniel Moult, Henry Fairs and Professor David Saint. He has also received conducting training from Paul Spicer and Daniel Galbreath. During his time in Birmingham, Dylan has had the opportunity to accompany large scale projects with choirs and orchestras, as well as conducting various choirs and perform as a solo recitalist. In addition to his studies at the Royal Birmingham Conservatoire, Dylan McCaig was appointed Organ Scholar at St. Chad’s Cathedral, Birmingham in September 2017. His duties include playing the Organ at Sunday services, Chapter Masses, as well as any other services required by the Cathedral. Dylan has also been given the opportunity to conduct and accompany the Cathedral Choir as well as visiting choirs in major services during the liturgical year. In addition, from 2017-2019, Dylan was heavily involved in the Cathedral’s Outreach Project, directing/accompanying the Junior Choir as well as playing for Outreach Services. From September 2020, Dylan will undertaking the role of Senior Organ Scholar at Liverpool Cathedral. Past performances have included playing at the Birmingham Town Hall, both Birmingham Cathedrals and St George’s Hall, Liverpool. In addition, he has played in masterclasses for internationally renowned organists, Martin Schmeding, Nathan J.Laube, Kimberly Marshall, and Pieter Van Dijk. Dylan is currently in the middle of preparing for his Major Project titled, ‘Membra Jesu Nostri’ which takes place on Friday 21st February 2020 at 7pm in St Chad’s Cathedral, Birmingham. Dylan will be exploring the work of Dietrich Buxtehude (a great influencer of J.S. Bach) using the Main Cathedral Organ as well as directing a solo SSATB Choir and Baroque Ensemble from the Chamber Organ. This music will be tied into the Cathedral using the theme of Jesus Christ, with the highlight of the concert being Buxtehude’s standalone work ‘Membra Jesu Nostri’. All ticket sales will be donated to Birmingham Children’s Hospital and providing financial assistance for youth volunteers from the Birmingham Diocese to visit Lourdes. For more information, check out: https://www.stchadscathedral.org.uk/events/major-project-membra-jesu-nostri-by-st-chads-organ-scholar-dylan-mccaig/ Today we are talking about the finding some repertoire you absolutely love. Listen to the conversation To see more of Dylan, check out: Instagram: @dylanmccaigmusic: https://picpanzee.com/dylanmccaigmusic Facebook: Dylan McCaig – Musician: https://m.facebook.com/dylanmccaigmusic/ Website (in development): http://www.dylanmccaigmusic.co.u

Vidas: Hi, guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra V: Let’s start episode 503, of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Maureen. And she writes: Vidas and Ausra, My three dreams are these. I would love to be able to play Widor’s Toccata, Bach’s Prelude and Fugue in D minor and to be a very good organ player for Mass including the Mass music and hymns. Thank you, Maureen V: What’s the deal with Widor’s Toccata? Why people want to play Widor’s Toccata? A: I guess this is probably the most known organ piece besides Bach’s D Minor Toccata and Fugue. V: But she doesn’t want play Bach’s Toccata in D Minor. She wants to play Bach’s Prelude and Fugue in D Minor. Which one? A: I don’t know. I guess she might mean Toccata... V: Toccata, right? A: and Fugue in D minor. Because there is really not such a famous D Minor Prelude and Fugue by J.S. Bach as his Toccata. V: Mmm-mmm. A: I guess what that might mean maybe people who like these two pieces, it’s okay. It’s sort of common way. V: Imagine what would happen—she will learn to play Widor’s Toccata and Bach’s D Minor Toccata, and become a very good player for Mass including music for Mass and hymns, right? She can play the hymns and everything else that is required for Mass, plus Widor’s Toccata and Bach’s D Minor Prelude and Fugue. So imagine she will play Bach’s D Minor Prelude and Fugue for the beginning and then Widor’s Toccata at the end. And then hymns and other Mass music in the middle. How would that sound? A: Well, after a few Sundays of these I think… V: Right! A: people will get tired. Because even the best piece doesn’t have to be played all the time, over and over again. V: Yeah. I think there is such a variety of organ music, vast variety that people don’t even, not only know about but don’t even, are not aware of them, right? You cannot know if you like those pieces because you even don’t know they exists. A: True, that’s true. And while talking about Widor’s Toccata, well, if you would listen other great French masters, and their toccata’s, such masters and Duruflé, Vierne, well, then might this Widor’s Toccata wouldn’t seem to nice to you. Because, honestly, what I think about for me, it sounds quite primitive. V: Mmm-hmm. A: And the same over and over again. V: True. It’s the most popular organ toccata, obviously, besides D Minor Toccata by Bach, but not the most artistically interesting, I would say. A: True. V: Mulet Carillon Sortie is much more interesting to me. As you say Dureflé’s Toccata is such a fantastic piece. But all of them require at least intermediate organ skills. A: True, and you should know really one thing—when you are picking up and playing the piece that the whole world knows by heart, such as Widor’s Toccata and Bach’s Toccata, you need to be brilliant in it. Otherwise it will be just a filler. V: Yeah, it will be a joke. A: True. Because in our school we have all these, such concerts, its traditional concerts. It takes place each year before Christmas break. It’s called Viva La Musica. And we have big competition because everybody wants to participate in it, and what teachers do, they select very well-known pieces for various instruments. V: Mmm-hmm. A: And I stopped going to that concert because then you are picking up really popular repertoire that everybody knows. You need to do it on the highest level. V: Yeah. I just remember this summer, I think, was one concert at the cathedral where one organist played something really recognizable to general audience, and there were two tourists from Russia. And Russian tourists are generally musically quite… A: Advanced, you mean, yes? V: Yes, advanced, and they have… A: Knowledgable. V: Yes, knowledgable, and they have good taste in music because of Russian music education obviously. A: And organ recitals are very popular in Russia because we don’t have organs in churches, obviously… V: Yes. A: because of the Orthodox of traditions. So they know that this concert repertoire. V: So this organist played the D Minor Toccata, and… A: And she was really sloppy. V: and very, very sloppy. Was it a lady or a man, do you remember? A: A lady. V: Lady. Okay. So then those two tourists left in the middle of the recital. A: True. V: Right? I’m not saying Maureen will play those pieces at the recital, perhaps not yet at least, but if you ever want to play them in church, then consider raising your skill level at least to the intermediate level. Basically before playing Widor’s Toccata, you need to be able to play in public, at the good level, easier toccata’s, like Gigout Toccata, Dubois Toccata, Boellmann’s Toccata. A: That’s right, yes. V: And before playing Bach’s D Minor Toccata and Fugue, consider playing in public at the good level, easier Bach’s free works, easier preludes and fugues. Maybe not even Bach’s, but maybe Eight Little Preludes and Fugues, and progressing through a little bit longer preludes and fugues, 533, 535, maybe Fugue in G minor 578, something like that. And then you might be ready for BWV 565, D Minor Toccata and Fugue. Right? But since Maureen has a dream besides those two big pieces to become a good, very good organ playing for Mass and play hymns, it means that she’s not there yet, right? So she needs to focus first on the hymns and easier organ music which could be played during Mass, as preludes, postludes, offertories and communions. A: True. And by expanding that easier repertoire, she can start to practice some harder organ works. And another thing that struck me, always strikes when people mention Bach’s Toccata in D Minor—it’s so funny because it’s possible that it’s not a Bach’s piece. V: Yes, it is possible. A: Because it’s so bizarre… V: It might be… A: comparing to his other pieces, other toccatas. V: It might be his youthful work, right? His student time work when he was maybe 16 years old. What kind of masterpiece is this? A: I know, so even while comparing Bach with his other works, I don’t think D Minor Toccata is the greatest piece, that… V: Yeah. A: J.S. Bach has written. V: It was made popular from 1940’s, Walt Disney Fantasia, when it was arranged for the organ and performed as a soundtrack of the movie. Hollywood made it famous, so it’s not Bach’s masterpiece that, not Bach’s genius that made it famous. A: I know because when you are thinking about pieces like E Minor Prelude and Fugue which, or Eb Major Prelude and Fugue from Clavierubung Part 3 and other great works, I think it’s, you cannot even compare those. They are so different. V: And Bach would have thought of this piece as a masterpiece. He would surely have... A: Published it. V: preserved and published for future generations, like Clavierubung. And we have Eb Major Prelude and Fugue from this collection. So. And the last thing that is missing from Maureen’s answer to me, I usually ask people about their dream in organ playing and challenges that they have to overcome in order to reach their dream. And she didn’t write anything about the challenges. A: True. V: And that’s what is the most important thing. We might talk for hours, right, about what she needs to do, but we don’t know anything about her. A: Mmm-hmm. V: What’s stopping her? Why she cannot play hymns now? So, guys, please be more—I wouldn’t say more specific, but be more honest, right? And tell us everything that you want to, that you want to say. Tell us everything that you wouldn’t say to anybody else, because we might know your situation then better and be able to recommend some things for you. Otherwise it’s just theoretical talking which may or may not help. Okay. This was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: Please send us more of your questions. We love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice… A: Miracles happen!

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 280, of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Ana Marija. And she writes: Hello! I am going to play a recital with my violinist friend on historical short octave organ (with no pedals, 8 stops). But we have some trouble finding repertoire, that is suitable for this organ. For the solo organ part, I will be playing some music by Byrd, Tomkins, Sweelinck, Frescobaldi and Froberger. Do you have any other idea? But mainly, we have a hard time finding pieces for violin and short octave organ. We would really appreciate if you could help us with any suggestion!:) Thank you for your wonderful work and help:) Ana Marija V: Do you think, Ausra, that playing above mentioned composers such as Byrd, Tompkins, Sweelinck, Frescobaldi, and Froberger, would work on that old organ? A: I’m sure it will work. Definitely. V: What else could you play for organ solo? A: Well, I think there is more music that you could do, because these all composers mentioned, except of course Froberger and Frescobaldi, come from Fitzwilliam Virginal Book. So anything in those two big volumes would fit, for historical with short octave. V: And Frescobaldi wrote, what Fiori musicali, probably, suitable without pedals. A: Yes, but of course you could also play something from Tabulatura nova by Samuel Scheidt. I think that will work also. V: That’s right. A: Because it’s also only for manuals. V: If you take Tabulatura nova, could you play the three lower parts with the keyboard, like on an organ and let the violinist play the upper part? A: Yes. That’s one of the possibilities that you could digest some pieces from Tabulatura nova for violin and organ. V: Hmm-hmm. That’s the easiest probably solution. Three volumes, plenty of music to choose from. But we also found a couple of suitable collections to work on, the Spanish Cancionero de Pallacio from the Renaissance period, from mid 1470’s until the beginning of 16th Century. Basically it has music of vocal polyphony for three or four parts. So you could easily play the three or two lower parts on the organ, and let the violinist play the upper part, with perhaps diminutions. A: Yes. Because if you would just play throughout, straight through, without adding any ornaments and diminutions, it might sound boring. So you have to improvise a little bit. V: Because it’s vocal music and the entire interest is done by voices with text and if you can’t hear text while playing instrumental music, then you have to add something. A: Sure. And I think that some of French chansons or Italian canzonas would work in the same way—that violin would play the upper part with some diminutions and the organ would accompany playing other voice. V: Definitely. Madrigals. A: Yes. Madrigals too. So French chansones and Italian madrigals. V: What about motets? Religious Latin music? A: Well, you could do them too, but I don’t think it would sound probably as good as madrigals and chanson. V: Imagine you’re an organist those motets on one organ. You would play diminutions, like Scheidemann did from the motets by Orlando de Lassus, for example, or Hans Leo Hassler. So you would need your right hand to be playing solo passages a lot, and the left hand and pedals if you have pedals, the lower parts. A: Well, but in this case we have no pedals. We have short octave, so I wouldn’t do motets, for this particular concert. V: Yes. With pedals you can do even up to six parts on the solo organ. But without the pedals, I guess three or four parts would be maximum. A: But anyway, in this case you will have adjust somehow because you won’t find original compositions specifically written for organ with short octave and solo violin. V: We can give links to these collections we’re talking about in the description of the conversation in the transcript, so that people can click and visit the scores in public domain. A: So nice you can use them freely. V: Yeah. And what about Michael Praetorius, dances from Terpsichore collection from 1612? A: I think it should work too. At least some of those pieces. V: Mmm-hmm. They’e very fun to play. We listened to CD of this collection and we’ve been to some of the concerts of early music ensembles playing Michael Praetorius. A: That’s right. V: Wonderful music if you have the right instruments. So violin and organ could play some of these too. A: Definitely, yes. So you just need to check this collection and then to decide what to do with it. V: Right. And there are additions with original notation, with various clefs, but for people who don’t like various clefs, there are modern additions. A: That’s right. V: Okay. So what are the closing remarks, the general ideas for people for searching for suitable repertoire like that, for ensemble music, chamber music form 17th or 16th Century? A: Well that’s all the time you will have to adjust somehow. Probably you won’t find the original that would suit you right away, so that’s the beauty of this kind of music. V: Have you played with a violinist, Ausra? A: Yes, I had. V: A good violinist? A: No, I haven’t. V: Only a bad one. A: Yes (laughs). V: But you played later music. A: Yes, I played Bach. V: Mmm-hmm. A: Sonata for violin and organ or harpsichord. V: Before this conversation started, we were discussing with Ausra some ideas, and Ausra thought if Bach would be suitable, for Bach’s violin sonatas would be suitable for this kind of arrangement on the short-octave organ and we concluded that no, probably. A: No, no. V: Why, Ausra. A: Well, Bach’s music is too complex for such kind of instrument and this kind of instrument needs earlier repertoire. V: And by complex, you mean, chromaticism's. A: Yes. V: In the left hand part. A: That’s right. V: In the bass octave. And we have to remember, that short octave doesn’t have accidentals. A: That’s right. V: No C sharp, no D sharp, no F sharp, no G sharp, only B flat I think. A: So it limits your variety of your repertoire. V: Right. Some of the 17th Century and even 18th Century organs have sort of version of short octave, but without C sharp, or without C sharp and D sharp, so you could have accidentals starting from F sharp. Then some of the later music would be possible to play but I guess this is not the case with this small organ without pedals. A: Definitely, yes. V: Thank you guys for writing those wonderful questions. Please send us more of your challenges. We love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice... A: Miracles happen!

This blog/podcast is supported by Total Organist - the most comprehensive organ training program online. It has hundreds of courses, coaching and practice materials for every area of organ playing, thousands of instructional videos and PDF's. You will NOT find more value anywhere else online...

Total Organist helps you to master any piece, perfect your technique, develop your sight-reading skills, and improvise or compose your own music and much much more... Sign up and begin your training today. And of course, you will get the 1st month free too. You can cancel anytime. Join 80+ other Total Organist students here Sam writes that his goal is to become a church organist, and perform all organist functions from accompanying the congregation and choirs, to playing the liturgy (Lutheran and Catholic), and also be able to improvise.

The three things that are stopping him from doing this are lack of strong foundation, repertoire that will make him progress, and good practice techniques. Sam is right about the importance of having a strong foundation to your success in organ playing. But actually overcoming his other challenges (finding graded repertoire and applying good practice techniques) will most likely build his foundation for him. So what you need to do, if you face similar obstacles to Sam's is always remember how you can find a suitable repertoire. This is done by the following way: A good repertoire should be a quality music and it should make you stretch (but not too much). It shouldn't be a piece which you can sight-read without any difficulty. On the other hand, you should pick a piece which you can imagine performing in the next few months (not years). So what are the basic guidelines in determining whether or not your piece is suitable for you to learn? It's actually very simple: If you can sight-read separate voices of this piece at a tempo which is 50 % slower than a concert speed with 5 mistakes per page or less, then you can do it. Anything less than that will be a long shot for now. Sight-reading: Menuet-gothique (p. 4) from Suite Gothique, op. 25 by Leon Boellmann, French Romantic composer and organist. Hymn playing: He Was Not Willing People like playing what they like playing (myself included). Most of us have a list of favorite composers or favorite pieces we want to learn sometime.

But some who have the curiosity to search for something new, like the surprises that come from discovering a collection or a composer they didn't know existed and playing music they didn't think they might like. So here are the two questions: 1. When was the last time you played something you didn't think you like and discovered that it's wonderful? 2. Would it be worth to do it more often? (One of my favorite places to look for unfamiliar music is here). [Thanks to Marcel for inspiration] |

DON'T MISS A THING! FREE UPDATES BY EMAIL.Thank you!You have successfully joined our subscriber list.  Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas

Authors

Drs. Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene Organists of Vilnius University , creators of Secrets of Organ Playing. Our Hauptwerk Setup:

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

This site participates in the Amazon, Thomann and other affiliate programs, the proceeds of which keep it free for anyone to read.

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed