|

I knew this day would come but I didn't expect it would come so soon when I'm 43... At night I had a dream where I was in my church and some tourist asked me, "Why are you so stuffed, grandpa?" It was an interesting day. It started with me doing 19 pull-ups and 6 ring dips. After breakfast I went to the church but met my former boss from school. Today was his 60th anniversary but I forgot to congratulate him. I wonder why? When I arrived at church I hoped to tune some reeds before tomorrow's organ duet recital. My assistant was @drugelis and she had to press the keys for me while I tuned the pipes. Before she arrived, I wrote my diary and colored Pinky and Spiky comic about piglet turning into a pig. When I saw @drugelis, we were getting ready to tune but our security guard from the church called me and asked me to be silent for 15 minutes because downstairs journalists from TV were interviewing an organbuilder. This was an organbuilder Rimantas Gucas who's company had reconstructed the pipe organ at our church 19 years ago. I completely forgot about this interview, even though I reserved the time for them myself. When they were finished, they came to the organ balcony and continued shooting inside of the organ. Then they asked me to play the organ so I changed my shoes and improvised for a few minutes. In about 3 weeks we can see the result of today's interview on the national TV. When we were over, I left @drugelis at the church to practice and I went to drink coffee with the organbuilder. When I came back @drugelis and I started tuning the reeds of the Oboe 8' of the Swell division as well as the Pedal Trompete 8' stop. I wanted to show you guys the process so after I was done, I asked @drugelis to press one key and I climbed to the pipes of the 2nd manual and made tenor G pipe of the Oboe 8' stop out of tune and then tuned it back again. You can see this process in this video: Before @drugelis left the church, I assigned her to the team who transcribes fingering and pedaling for us from my slow motion videos. She said to me her largest challenge right now is finding out the correct fingering and pedaling to play with so I'm sure she will find transcribing process very helpful. I made a video for her with 10 pieces from organ method by the Belgian organist Jacques-Nicolas Lemmens who practically invented French Romantic organ school and she will try not only to transcribe the fingering and pedaling for me but also to play them. Most of those pieces are trios for two manuals and pedals. Right hand plays the top voice, left hand - the middle voice and the feet - the bass voice. Such texture is very beneficial for educational purposes because each part is so independent. @laputis and I came back home today quite tired so we decided to postpone our organ duet practice for tomorrow morning. It's better to take a rest and start a new day with a fresh head on the day of the recital.

Comments

SOPP305: I enjoyed the Bach organ tour but the big surprise was how sharp most of the organs were10/15/2018

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 305 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Alan, and he writes: Vidas, we are back from our travels. I enjoyed the Bach organ tour but the big surprise was how sharp most of the organs were. It wreaked havoc with my absolute pitch and made it very difficult to play. It didn't get easier, but I didn't push it too much as there were others waiting for a chance to play the organs. For something else to do I took measurements of the temperament octaves of many of the organs in order to make some comparisons. A podcast on coping with different pitches would be good. V: So, Alan is already introduced to historical temperaments, right? A: Yes. V: This is nice. A: True. V: Was it difficult for you to adjust, Ausra, when you first encountered different pitch levels in the tuning of different organs? A: Well, a little bit, yes, but I wouldn’t complain about it, actually, I liked it so much. V: What was the first organ that was different from A440 that you played or heard? A: Actually it was a small organ built by John Brombaugh in Gothenburg, Sweden, in Haga Church. That was my first organ. V: So, probably the same for me. A: That’s right, and because it has split keys, I remember that you could not figure out which are flats and which are sharps, and I had to do it. And somehow, I did it fine. You just need to listen, really. V: On that organ, I chose E major Preludium by Buxtehude with four sharps—very stupid idea. A: Well, at that time, we simply didn’t have any idea what the historical temperaments are. V: And what did you play there? A: Well, I played, I think, Preludium in G minor. V: Much better choice! A: Yes. It was better. V: With two flats. Anyway, so the tuning was quarter-comma meantone, and the pitch level was A=465, I think. A: Yes. V: Half step higher. A: Yes. And, you know, a couple remarks about “absolute pitch,” as Alan called it, or I would call it, “perfect pitch.” It’s usually not a pitch that is related to this, it’s usually your memory. Your musical memory. You simply memorize everything at A440. V: And the reason I asked him if it got easier when he touched the keyboard and started to play is because for me, somehow, it became easier. I forgot somehow, but maybe I spent more time than Alan on the organ. A: Well, let’s say, I used to have to play sometimes, even during the same recital, on three different instruments. I remember accompanying at Eastern Michigan University, for example, and I had to play on the organ, on the harpsichord, and on the piano. That was hard work. And I remember in one recital, I had to do Sweelinck’s Fantasia Chromatica on the harpsichord, which was tuned quarter-comma meantone, and then I played on the organ Bach/Vivaldi Concertos, which was tuned in A440. And for me, it was really difficult to go through the first page, and after that it was ok. V: You mean of Bach? A: Yes. V: Because you played Sweelinck first, and adjusted, got used to it, and then suddenly had to switch to Bach—to the modern organ. A: Yes. But you know, after working for a while with historical tuning, when you go back to 440, you see that it’s really harsh sounding. That there are no pure intervals, and everything is so, so out of tune, actually! V: Did you notice that piano sounds milder with equal temperament than the organ, actually? A: True, because I think the pipe sound is so much more prominent than the piano. V: And the sound doesn’t fade. A: True. V: So, yes, it needs some adjustments and some experience with different instruments, but each new instrument gives you new perspective—new experience, right? A: True, and I think if you are getting in trouble adjusting to a historical tuning, I think working on the 440 instrument, you need to transpose more often, to play the same pieces in different keys. V: Mhm, why? A: Then it will be easier for you to adjust. V: Oh, transpose… we need to ask Alan if he practices transposition then! A: True. V: At some point, I remember making a few videos of the same piece in different keys—a Two Part Invention by Bach in C major. I played it in C major, in F major, and in G major, recorded on YouTube, and I transposed it into all the other major keys when I practiced, but didn't record it yet. So, it really helps to do this regularly. A: Well, and another thing, if you want to adjust to historical tunings, if you have access to a harpsichord, then it’s easier to do, because harpsichord is an instrument which you can tune in different tuning systems very easily, so you could practice. V: Or a clavichord. A: Or a clavichord. I think it’s easier to access a harpsichord, probably, than a clavichord. V: Right. A: But I think it’s all a mental thing. V: But I think Alan seems to have enjoyed this experience, right? But when he started to play that it was difficult, right? Or when other people played, he couldn’t listen to the original keys. I myself remember in Sweden, back in 2000, in Gothenburg, so other people played C major. I remember Bill Porter played 545 Preludium and Fugue in C major by Bach. This was one of… A: In Örgryte V: ...In Örgryte New Church one the first times I heard this piece, actually. And he announced that this piece will be in C major. And I prepared myself in C major, you know, my “perfect pitch system” based on 440, and he started to play, and it sounded D flat major, and the whole time, while being downstairs, I was mentally really struggling to think, “What is happening, and what is he actually playing?” Not, “What I’m hearing,” but, “What is he playing?” But again, when I started to play this on organ on another occasion, not right away, but after a few minutes, I think, it became easier. A: Yes, for me, it takes about one page to adjust. V: Right. So, Ausra, do you recommend people trying out different historical instruments and going on tours, like Alan did? A: Yes, I think it broadens your perspectives in general. I think it’s a wonderful experience. V: Tuning and pitches is just one side of the story. Another could be adjusting to the touch, adjusting to the bench height, or to the distance of the manuals when you have to reach the top manual and it’s very far from you… A: But if we are talking about tunings and you see how different each key sounds, actually, then you understand what all those treatises about the meaning of the keys is. V: And also in many historical instruments, the layout of the stops is not vertical from top to bottom, but from right to left, or from left to right horizontally! And you have to reach very, very far from the distant stop handles, and that makes it very difficult sometimes, and you might wonder if they really played with assistants or made less stop changes or what! A: That’s true! And it also teaches us that when going somewhere, abroad especially, on an unfamiliar organ, you need to find out about them in advance as much as possible, so that you will be mentally prepared for it. That it wouldn’t catch you by surprise. V: Like a short octave, right? A: Yes. V: In short octave, some of the lowest semitones are missing… sharp keys are missing… no C sharp, no D sharp, and sometimes even no F sharp and G sharp. So, if you don’t know this, and you are scheduled to play a recital on some historical organ with short octave, and you are used to playing a modern organ, then you don’t know what to play in that left hand section. Therefore, if you find out in advance, you can actually practice on your own keyboard at home or in a church with approximations of the target organ. A: Usually next to the stop list of the organ, you get a compass of keys, so you could find out about it from it. V: Thank you guys, we hope this was useful to you. Enjoy your travels, and enjoy experiences on other instruments—as many as possible, because each new organ gives you a new perspective. It’s like driving a car, right Ausra? A: Yes. V: The more you drive, the better you become at adjusting to each new vehicle. Please send us more of your questions; we love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice, A: Miracles happen. AVA180: I'm not sure if F# major key would sound well on the organ with Kirnberger III temperament3/17/2018 Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 180 of Ask Vidas and Ausra podcast. This question was sent by John and he writes: Hi Vidas, Thanks for your encouragement, my main concern with the repertoire fitting the organ is Festive Trumpet Tune, which is a modern piece, and near the end it has a trumpet fanfare and then modulates from F major up a semitone to F sharp major, and the main theme at from the beginning repeats up a semitone. I'm not sure how this unusual key would sound with Kirnberger III temperament, which I have never heard of before! On equal temperament organs it sounds fine. V: So John is coming to Lithuania in just four weeks I believe and he’s preparing to play some beautiful organ music on Kirnberger III temperament and one of his problems is this “Festive Trumpet Tune” which modulates to the tonality of six sharps which would might sound harsh or too harsh on our organ. Don’t you think or not? A: Well people used to play even you know harder music on our organ. V: It wouldn’t be a problem? A: I think it should be OK. V: Remember you played your Vierne Symphony Number 3 there. A: Oh no. I would never do it but still I played it and it was fine. V: It’s in F sharp minor but it has obviously segments in F sharp major too. A: Sure. And so many diminished chords. Like diminished chords one after another, long sequence of diminished chords and no resolutions. V: And I suspect that his trumpet tune in F or F sharp major wouldn’t be as harsh because it’s not as dissonant as Vierne’s harmony. A: Yes, that’s true. I think it should work OK. V: It totally has some basic tonic, subdominant, dominant chords probably. Maybe some modulation in between but not too chromatic. A: I know and since it’s not entire piece it should work just fine. And talking about that I played Vierne’s symphony, you played Messiaen “Diptyque” on that organ. V: I did? A: Yes, on that organ. V: Oh, I never… A: Do you think it sounded better? V: I never would repeat this piece on that organ today. I was young and stupid. Now, I’m just stupid. A: Not young anymore. V: Yeah. Whenever I improvise on this instrument sometimes I use different modes and jump from one key to another and I definitely use F sharp major from time to time. But then I always listen to what I play how it sounds right? And it does make a difference on this temperament this type of key. It’s a little bit more colorful that F major. F major is very calm and peaceful. F sharp major is more dramatic. But maybe it’s a good thing. A: Yes, that’s what I like about Kirnberger III. But you can play quite a lot of music on it. But it sounds much more interesting when in equal temperament. So it’s real nice. V: What other surprises this organ might throw at John? A: Well, don’t ask me. V: John also wrote that he is worried about sharps and natural keys being in reverse colors. C sharp is for example white and C is black. And he has never played this type of layout before. A: I don’t think this will be a problem you know. I never even thought about things like this. V: But do you remember the first time you played this type of keyboard? A: Yes, I remember. V: At musical academy right? A: No. V: No? A: At my school, National Ciurlionis School of Art. On that small organ. V: So you practiced in the practice room. Was it a weird feeling for you after playing piano for a lot of years? A: Actually it was a nice feeling. V: Nice or weird? A: Well, nice. V: Nicely weird? A: Nicely weird. Yes. V: Or weirdly nice? A: Whatever. But it was a nice thing. My piano teacher, since I played Bach well you know on the piano so as an award of that she allowed me to play it on the organ. V: Um-Hmm. A: Which stood in her classroom. V: It’s a nice award, right? I think all the teachers could have this type of award. For example if they work hard enough with their students their students could let them play the organ. Instead of getting the salary. The principal of our school could have the system, would be cheaper though. A: (Laughs.) Do you think he would still be able to keep his employers? V: Oh, some of them yeah. Some who pay for this privilege to play the organ. Would you pay? A: Well not for that organ that the school has. V: No, it’s too boring I believe. A: Too shabby. V: Yeah. But now I think John will have many more problems than just adjusting to the different layout of the colors. A: Yes, I think colors should be still fine, you know it shouldn’t bother. I think maybe during the first ten minutes of his practice. But then it’s just fine. V: I remember my other students who first tried the organ at school with sharps being white. Some of them said “Oh, it’s interesting feeling.” But nobody really messed up with their pieces or played incorrectly because of that. Maybe it was a weird different feeling, but it didn’t distract them too much. What will distract of course John, is the heavy mechanical action. A: Yes, I think this will be the hardest thing to manage. V: If he is used to you know, maybe lighter mechanical action organs in Australia. But also if he can play piano in between now and his coming that would help. If he would play with couplers that would help too. A: Sure. V: Excellent. So we hope people will not be too disturbed if they travel for example anywhere and discover a different layout. It’s good to see different kinds of layout, right? White-black, black-white. A: Yes, or sometimes you could get like brown keys, like in our home. V: Brown and browner. A: Yes, sort of dark brown and light brown. V: Yes, or in my house, my former house where my Mom now is, she has a piano with colored keys now. And that helps her to memorize where C-D-E is. A: Outrageous... V: She puts stickers, colored stickers on top of keys. A: If she would be my kid I would punish her for doing it. V: But you know she is a graphic artist maybe she thinks in colors. A: I know. V: Alright guys. We hope you can experiment with different kinds of colors and layouts and don’t be too distracted by them because the most important thing is not to get attached to anything. The organs are as magnificent instrument as they are because of variety, right Ausra? A: Sure, so you have to adjust each time, but that’s the beauty. V: And each time you play those kinds of instruments you will probably make a small discovery about yourself, about this instrument, and about the music that you are playing. A: Yes, and at the end of your life you can write wonderful memoirs. V: Maybe ten volumes of them. Or even start memoirs now like a diary and publish them on Steemit and earn rewards and maybe in time those rewards can become your additional stream of revenue. Thank you guys. This is Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: And remember when you practice… A: Miracles happen.

Vidas: Let's start Episode 41 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. And Ron sent this question to us:

"Hi Vidas and Ausra, You are the best teachers. The pedal training is really helping me to integrate my entire body into organ playing. It is a slow process, but well worth it. As you learn to slow down and get things right - which doesn’t happen overnight, especially since the learning process is very biological and physiological—it is as if you are learning to keep your feet underneath you, metaphorically. Practice goes one step at a time, and life goes one step at a time. I have a question, rather questions. When playing on the pedals, for instance, E flat then D, then C sharp then D, the D sounds different in each sequence. There is a sort of shift of frequency in the mind—the D sounds higher in the first as compared to the second of the sequences. However, if you start on the D and go to E flat, then D to C sharp, the D sounds just fine, the same frequency. I realize it is psychological. It reminds me of the phenomenon of comparative colors, where one color seems shifted a bit depending on which other color it is next to. Is there any explanation for that? Does it affect ear training? Is there an exercise to practice discerning notes like that? The most interesting part about learning the organ can be these small things. Thank you for your great programs!" So, interesting question, right? Ausra: It's a very interesting question. Vidas: Not too many people bother about those intricate details. Ausra: And not many people actually notice them. Vidas: What I think is maybe it has something to do with temperament? Remember, a few weeks ago we played in Stockholm on the old organ at the German church and it had this mean-tone temperament. And in mean-tone temperament, when you play chromatic scale, certain notes basically sound higher and certain notes - higher. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: So if you play D, as Ron says, and then Eb and then D and then C#... C# would sound lower. Ausra: Sure, that's right. Vidas: Even though in D minor it would be like a leading tone, but C# is lower in mean-tone temperament and Eb is sort of closer to D. Ausra: Yes, and it also might be related to the position of the pipes in the organ case, too. Vidas: Exactly. I don't know what kind of organ does he play but if we have this classical C and C# pipe organ layout, then pipes are positioned in diatonic steps: C-D-E-F#-G#-Bb are on the left side and C#-D#/Eb-F-G-A-B are the right side. Ausra: Sure. Vidas: So, this means that D is one side and C# and Eb are on another side. Ausra: And depending if you're ascending or descending from that D it might sound different while going one way or another acoustically because pipes are standing on another side of an organ case. Vidas: That might be it. Ron also writes when you play D and go to Eb and then to D and C#, D sounds just fine, the same frequency. It's a different feeling when you go upward or downward, for him. But maybe it has something to do with some kind of physiological feeling what kind of note is next to each other? Ausra: That's true. For example, when I practice on the pipe organ, sometime I hear a principal chorus. For me it's the same as there would be human voices singing. Vidas: Yes. Ausra: I get this feeling. It's really strange. Vidas: And some people can really discern colors from chords. Ausra: Sure, like Olivier Messiaen. Vidas: And Stravinsky. And maybe Ciurlionis. Ausra: I don't know about Ciurlionis. Vidas: His musical works are so influenced by his paintings and vice versa - paintings are influenced by music. So the second part of Ron's question is "Is there an exercise you can practice discerning notes like that?" Can you develop through training where you can hear the sounds differently? Ausra: Well, some people might, some - not. Vidas: Yeah. It depends on the personality probably. Ausra: But I think Ron would be an excellent organ tuner. He could tune organs very well because he hears these vibrations. So that's an excellent skill. Vidas: Right. And of course it's not easy to hear it for regular people, so if Ron hears this, it's a gift. Ausra: Yes, definitely. Vidas: Keep it and practice by hearing vibrations even more. The more you practice, the better you become by listening differing vibrations. Even if you go to the church where somebody else is playing, walk around because you will hear different vibrations. Ausra: Sure. Vidas: For example, have you ever walked around when myself or other people were playing in our church? Ausra: Yes, and it sounds very different actually from different angles of the church. Vidas: How different? Ausra: Well, very different. Vidas: And what is different? Ausra: Well, everything. Vidas: Like what? Ausra: The power of the organ. The sound actually in some places is really loud but in other places it's quite soft. And in some parts you can hear different organ stops. So it's very interesting. Vidas: And even different pitches making themselves louder than others. For example, under one balcony or one column you can hear Eb, I remember very well. Or when you climb the organ balcony on this staircase, you can hear the pedal voices very well. Ausra: Sure, it's very interesting. Vidas: Acoustical marvels. Ausra: I wish modern architects would think about acoustics when they are building new churches because some of them have dead acoustics. Vidas: Oh, this is too much to ask, I think. A lot of architects even don't think about organs. Ausra: Sure, definitely. Vidas: Don't leave the space for organs when they plan the space. Excellent, guys. Please send us more of your questions and the best way to connect with us is through our blog, subscribe at www.organduo.lt and reply to any of our messages and we'll reply to your questions on this podcast. And make sure you also practice pedalwork, like Ron. By the way, do we have a course recommend to people who want to improve their organ playing? Ausra: Yes, we have. Vidas: Like Organ Pedal Virtuoso? Ausra: Sure. Vidas: Because Pedal Virtuoso Master Course is designed for you to be able to play any type of pedalwork easily and without struggle. At first it might be difficult, right, Ausra? Because when you play those scales and arpeggios some people send us their feedback and they want to quit. And some people do quit but those who persevere later are very very joyful about this course because you can play scales and arpeggios legato, right? This is the basis for the modern technique and then you can really master any type of organ pedal line in organ composition without any struggle at all. Ausra: Sure. Nothing comes easily at first but you must put some efforts and then you will have an excellent result. Vidas: Wonderful. So guys, this was Vidas... Ausra: And Ausra. Vidas: And remember, when you practice... Ausra: Miracles happen. By Vidas Pinkevicius (get free updates of new posts here)

I hate when people ask me to tune the organ before they even had practiced on this instrument. Maybe no tuning is needed. Beside most often organists who ask, actually don’t notice that it’s tuned. All they care about is what do other people think of them. The other day of my organist friends had to play a recital in our church and asked me if I can tune some reeds. I said yes. So I asked one of my students to press the keys for me (he had a nice long practice afterwards) and went to church. Here’s what I learned: 1. In winter, reeds need to be lowered. It’s quite cold in the church right now. 15 or 16 degrees Celsius. Above freezing. It’s cold to me because the church is actually heated yet when you sit for hours on the organ bench, your butt gets cold anyway. When they built this organ, the organ builder tuned it at 440 Hz when it was 18 degrees. So now in the winter the pitch level dropped a bit. Last time I checked it was 437 Hz. And it’s tuned in Kirnberger III. Metal principals react to temperature changes more than reeds. So now the reeds for the most part are too sharp. I had to check each of them and many needed to be flattened. After a while you get used to this. And don’t even check the tuning machine. They’re sharp. Not too much but enough to cause unnecessary vibrations. 2. Some reed pipes need to be raised. But once in a while I heard that a few pipes sounded flat. That seemed strange. Maybe those pipes caught a cold? So I had to be careful and spot those pipes and raise their pitch level a little. 3. Check the pitch level of middle A before tuning. Do you know what was the biggest mistake I once made while tuning the reeds? I tuned some stops but didn’t check the A and some other metal pipes. So I got it all wrong. Cost me 3 hours of work. But a good lesson, I think. 4. When pipes don't speak, clean them. You can find so many strange things in the pipes that clogs them from sounding. Mice poop, bat and bird poop, insects, dust from construction. I once found a mummy of a fly trapped in the shallot. Took a picture as a souvenir (see above). Didn’t want the fly, though. I found a few reed pipes that didn’t sound. So I took them apart, tested how clean they were and sure enough, some of them had dust in them. When I cleaned them they started to speak. With big pipes it’s a fairly difficult work to take them apart. You have to be careful and lift them, turn the resonators gently so that the blocks would separate from them. After that you have to look at the tongue and see if anything has stuck. Then you need to take the tongue apart and with a soft brush gently clean them. Finally, put it all together and test how the pipe sounds. 5. The tongues need to be in the exact position with the shallots. Strange thing happened the other day when I was tuning the reeds. One of the pipes didn’t sound but when I took them apart, I didn’t see any dust, insects or dirt. This got me thinking what else could have been wrong with it. Suddenly I realized that tip of the tongue was not leveled with the shallot. It dawned on me that if I remove the wedge, press a tongue a little bit inside, and put back the wedge, then the sound would magically reappear. What a clever idea! It worked. Now I know that the secret to the good speaking reed pipe is not only removing the dirt but also leveling the brass tongue with the shallot. 6. Tune C side first, then C# side. I had to tune the most often used pedal reeds which were positioned diatonically because of pedal towers. It didn’t make sense to tune these pipes chromatically C, C#, D, D#, E, F and so on because on the one side were the C pipes: C, D, E, F#, G#, and Bb and on another C#: C# D#, F, G, A, and B. So it was quicker for me to tune the C side first and only then do the C# side. Since pedal compass is about twice as narrow as that of the manuals, it took me not too much time to work on the pedal pipes. To my surprise, Posaune 16’ was more out of tune than Trompette 8’ in the pedals (maybe because I use it more often). 7. When there are central towers, tune in major thirds. The pipes of the Great and Positiv on my organ have central towers which means that not only there are C and C# sides for symmetrical design but in each side there are symmetry around the largest central pipe. In this way the pipes are positioned in major thirds. Because I didn’t want to be jumping from one side of the tower to the next, I asked my student to press the keys in the following order: C-E-G# etc., D-F#-Bb etc., C#-F-A etc. and D#-G-B etc. As I expected, Bombarde 16’ was more stable than Trumpet 8’ which had to be flattened most of the time. 8. When pipes are positioned in a row, tune chromatically. When I went inside of the Swell division, I knew that the pipes were positioned from the tallest to the smallest pipe chromatically. This is because they are not visible from the outside and no symmetry of design is needed. Because of enclosed Swell box, the temperature inside of it is a little higher than the rest of the organ and the Trompette 8’ usually needs to be tuned quite a bit. This time, however, I was surprised - it was more or less stable with just a few adjustments. 9. Double check each pipe after tuning. When you tune the pipe, sometimes it slips back to the previous state, especially with shorter tongues. Therefore it’s a good idea for my tuning assistant to hold the note while it’s being tuned and repeat it shortly when the tuner says “Next!” Before I knew this rule, I had a few cases where the organ pipes were tuned just before the recital but in the actual event some pipes were still a little off. So double check just to be sure. 10. Tune to Principal 4' of that division. One last advice is to traditionally tune the reeds to the Principal 4’ of the division on which they are positioned. Yes, I know sometimes this particular division might have principal 8’ or even 16’ as the foundation but somehow it seems to be a custom among organ builders to use Octave 4’ in this case. Oh, and by the way, my organist friend didn’t notice the tuned reeds at all. He just played almost everything loud and fast. That’s how he is. Not really a friend. More like a tank. By Vidas Pinkevicius (get free updates of new posts here)

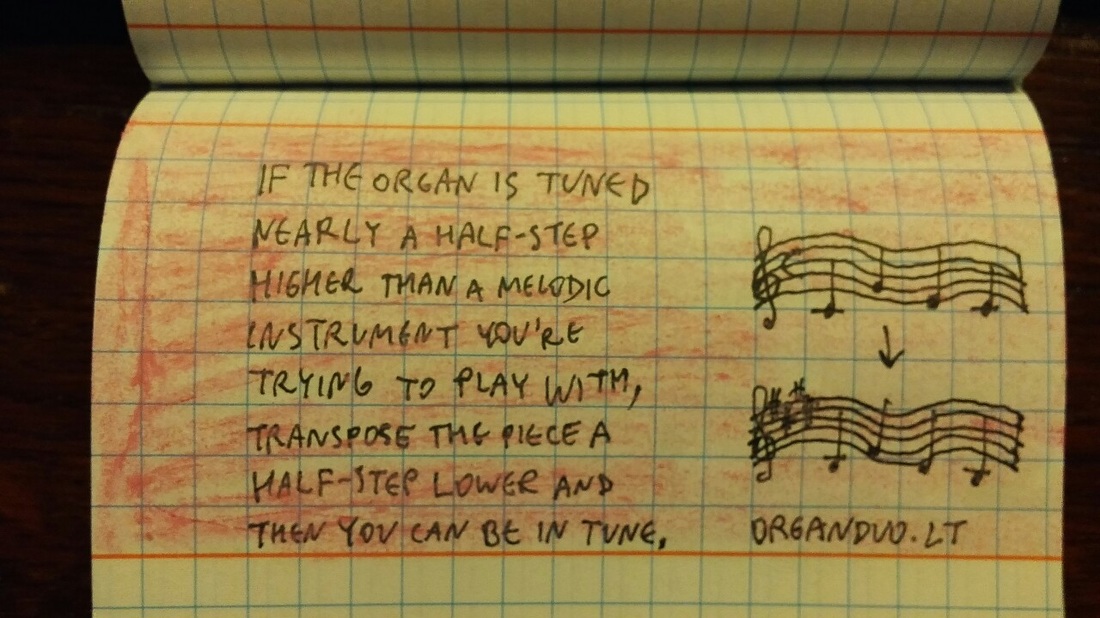

What's the tuning and temperament for Estampie, Estampie Retrove and 4 Pieces from Lochamer Liederbuch for which I prepared practice scores recently? Music of the Middle ages (Estampie) might have been performed on the Pythagorian temperament while pieces from the Renaissance - on some kind of Meantone temperament (most common - Quarter-Comma Meantone). The Pythagorian temperament is very easy to set up - tune 11 fifths pure (Eb-Bb-F-C-G-D-A-E-B-F#-C#-G#). Each of those fifths will be 702 cents wide. Almost as in Equal temperament (700 cents). By the way, 100 cents is a semitone in Equal temperament (such as C-C#). By pure perfect fifth I mean without any beats or vibrations. The result will be that an interval G#-Eb, although enharmonically would look like a perfect fifth (G#-D# or Ab-Eb) but in reality it's a diminished 6th - an ugly sounding "Woolf" interval. Also all the remaining fifths will sound beautiful but the thirds will be too wide (408 cents). The temperament for the Lochamer Liederbuch is another story. The Quarter-Comma Meantone temperament is a tuning system of 8 pure without vibrations major thirds. A pure major third will have a calming effect. It will be narrower (about 386 cents) than in our modern Equal temperament we have on the piano most of the time (400 cents). Here are those pure major thirds: C-E, D-F#, Eb-G, E-G#, F-A, G-B, A-C#, and Bb-D. How do we know this? In Estampie, we can hear a lot of fifths while in the Lochamer Liederbuch - major thirds are more prevalent. If you want to play those pieces, check out my practice scores of Estampie, Estampie Retrove and 4 Pieces from Lochamer Liederbuch with fingering and registration suggestions. (50 % discount is valid until January 11). [Thanks to Andrew fot this excellent question] Tuning with your partner can be a pain in the neck. Especially with a melodic instrument. Sometimes it's impossible but more often than not the solution may be found (although you or your partner may not like it). Here are 3 options: 1. Tune a melodic instrument to the organ 2. Transpose the organ part 3. Transpose the melodic instrument's part When you play on an old organ, sometimes transposing is the only option there is. That's why mastering this skill is essential for organists because string and wind players rarely have the capacity to do it themselves. Never let transposition scare you. Total Organist Christmas Special ends December 31

If you want to learn to maintain the instrument, getting to know it from inside out is the first thing to do. So make sure you spend a considerable amount of time inside the organ checking all of the windchests and the mechanical details of the stop handles as often as you can. Of course you will need to know how to handle the ciphers and regulate the mechanics of the organ. You will also need to know how to tune the pipes or the stops that get out of tune easily, such as reeds and stopped flutes. So get some basic tools for maintaining the instrument such as a screwdriver. But I strongly recommend that you get help from an expert organ builder who has lots of experience and who can teach you what you need to know. Trying to learn it on your own might seem like an easy way out but it might be pretty dangerous for the instrument. If you have no experience in maintaining an instrument and you are blindly learning from your own mistakes, you can make mistakes in the situations that can make damage to the organ. And damages can be quite costly especially if it is a historic instrument which is protected by the state. And even an organ builder who advises you and teaches you how to maintain it, has to have formal and official qualifications to work with historical instruments. But don’t be afraid to open the panels of the façade and to look inside the organ and see how it functions but dry not to cause the damage by touching things in a way that it’s dangerous for the organ. What I'm working on:

Writing introduction for the tomorrow's SOP Podcast #1 with the organ builder Gene Bedient. Writing fingering and pedaling for the Toccata by Charles-Marie Widor. Editing Part 3 of Sonata No. 1 by Teisutis Makačinas. Assisting Gianluigi Spaziani at his recital „Vater unser im Himmelreich“ at VU St. John's church. Transposing hymn setting "Jesus Sinners Doth Receive". Practicing 12 Technical Polyphonic and Rhythmic Studies Op. 125 by Oreste Ravanello and adapting them to fit Dominant 7th chords and their inversions. Practicing "Virtuoso Pianist" by Hanon in C Ionian mode (only white keys). Playing Office No. 34 from “L’Orgue Mystique” by Charles Tournemire. Improvising with Dominant 7th chords and their inversions. Composing "A Morning in the Countryside". Reading "A Beautiful Constraint". |

DON'T MISS A THING! FREE UPDATES BY EMAIL.Thank you!You have successfully joined our subscriber list.  Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas

Authors

Drs. Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene Organists of Vilnius University , creators of Secrets of Organ Playing. Our Hauptwerk Setup:

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

This site participates in the Amazon, Thomann and other affiliate programs, the proceeds of which keep it free for anyone to read.

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed