|

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas!

Ausra: And Ausra! V: Let’s start episode 571 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Diana, and she writes: “I’m struggling with keeping all fingers on the keyboard” V: Has this, Ausra, ever been a problem for you? Keeping all the fingers on the keyboard? A: No, it hasn’t. Have you had such a problem? V: Sure! When I was little. I remember that when I first started playing keyboard or piano, it wasn’t very obvious to me that I should keep all the fingers on the keyboard. A: But what do you mean? How can you play without keeping all the fingers on the keyboard? V: For example, your thumbs could be outside of the keyboard, you see, kids play like that usually at first if their teachers don’t correct them. A: Well… V: What about you? Did you always have a perfect posture? A: Yes, I think I was quite natural at the keyboard. Probably because of the structure of my hand, too. V: How is your hand structure different from mine? A: Just like J. S. Bach’s. I’m of course kidding, but you know, many years ago, before going to the United States, I worked at one private school for three years and taught piano there. And I worked with beginners—with first to third grade. So basically, I was the one who had to teach them how to play the piano, how to use the hand technique correctly, and what I noticed at that time is that all these kids had such a different type of hand! I never thought about it before teaching them. Because really, some of them would just sit down on the piano and place their hands so naturally, so well, shaped like a ball, as it should be… V: Or an apple… A: Yes, or an apple. And the thumb and the little finger would not stick out. But for somebody, I remember I had this one student who had really long fingers, and it seemed like he’s made out of jelly, maybe, or a gum, like a rubber. V: Yes. A: I could do nothing with his hands. They just didn’t work. V: Interesting. A: So… V: So it seems that Diana needs to hold an apple in her hand. A: Yes, and in general, I think when somebody asks questions like this, I think either their beginning technique instructions were taught to her incorrectly, or she simply doesn’t practice enough. Because it’s really a problem for just beginners. V: When I had little students who were practicing piano at school, I remember several children, most of them really liked the idea of holding an apple in their hands, or a ball, like a tennis ball. A: Shouldn’t it be a little…. Yes, I guess tennis ball, but for a small hand, V: For a small hand… A: Maybe it’s too big, a little big. V: Like an apple, you know? A: Well, you know, an apple can be various sizes! V: Yes! So I remember one of my students always asking for an apple. “Can I hold an apple please?” A: Just not to practice, yes? V: Yes. And I would always carry a tennis ball or a tennis size ball made from rubber, maybe, in the trunk of my car, and would bring it to class. A: I think I still have one of those balls in my book shelf in my classroom. V: Yes, it’s very useful. So Diana and others who play with random shaped palm position, and struggle to keep their fingers on the keyboard, one of the best pieces of advice that we can give is simply to hold a ball or an apple in their hand, and then try to imitate this position on the keyboard. A: But basically, I think this is a problem for beginners only, because as soon as you reach some sort of level, it should disappear, because your muscles will get used to that position. V: Obviously, yes. So it’s a temporary problem if she continues to practice diligently and build up her organ technique. Thank you guys, this was Vidas, A: And Ausra, V: Please send us more of your questions; we love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice, A: Miracles happen.

Comments

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas!

Ausra: And Ausra! V: Let’s start episode 552 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Joanna, and she writes: “Dear Vidas, The little finger on my right hand is giving me problems. It has been like this for a few years. I am afraid I will have to give up organ playing in a couple of years’ time because it is stiff, and it clicks and makes a jumping movement at the knuckles. It is a problem to play fast passages because of it. Is there anything I can do… practise more? Practise less? Exercises? Joanna” V: Have you ever encountered, Ausra, such a condition? A: No, actually I haven’t. And what I would advise to Joanna is that she might consult a physician first. V: Yeah, because it might be unique to her situation, and since we haven’t encountered it, we cannot really advise anything specific. A: Yes, but I would suggest definitely not to practice more, because it might do things even worse. So she really needs to consult her physician and to see what he or she will say. V: Right. But practice less, probably is a good idea. A: For right now… until she will get that consultation. V: Sometimes these problems might be because of overworking certain joints. A: Yes, it might be. But definitely, she needs to consult a physician because she hadn’t had that problem earlier. She was developing it for the last few years, so… V: And I think she writes the little finger of her right hand is giving her problems. I would suggest maybe doing a test while playing only the right hand part, and doing it really really slowly. It means probably that her little finger is quite tense. Maybe she can relax it, see if she can relax it and place it on the keyboard instead of lifting in the air. That helps. A: Yes, that’s often the case, that the fifth finger is sort of looking… V: Like a piglet's tail, right? A: Yes. V: Curled. So if she can relax it and place it on the keyboard, maybe the tension can also diminish somewhat. Right? A: Yes, that’s a possibility, but I think it’s wise to check up with a doctor to see if there’s a serious problem with it. V: Right. But for example, I have a thumb, for example, and my condition of the thumb is that it’s kind of curved in the wrong direction. The tip of the thumb is looking outward, not inward. And this is because from an early age I was taught to play correctly, but I didn’t pay attention, and today, if I want to correct this finger’s position, I need to do a very conscious effort, and it’s not natural to me. You know, I have to even probably hold my hand a little bit in order to relax it. So maybe Joanna can also see with her left hand, feel if there is a tension on her right hand little finger. Right? A: Yes. V: And then see if she can relax it and place it on the keyboard. Maybe Alexander Technique would be helpful to her, right? A: Sure. V: Okay. This was Vidas, A: And Ausra. V: Please send us more of your questions; we love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice, A: Miracles happen.

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 359, of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Jeremy. And he writes: Speeding up fingerwork. For some reason, my fingers feel sluggish. I have practiced with high fingers (a technique I use in piano) and shortening and lengthening the note values (like swinging or reverse swinging rhythms), but still seem to get stuck at one tempo. Also, have tried Vidas suggestions of stopping on every beat, then every other beat, etc. V: Ausra, do you have problems with speeding up, up to concert tempo, sometimes? A: Well, yes and no—because usually speeding up is not my main problem. V: Slowing down, right, is your problem. A: Well, keeping steady tempo is bigger problem, sometimes. V: Uh-huh. Right now I’m starting to practice Sonata Ad Patres by Bronius Kutavicius, a living Lithuanian composer, and it has a middle movement—very fast. And the style is minimalistic, and lots of repetitions, with minimal adjustments are going on, so have to constantly be aware of those changes. But my fingers are not ready to play fast, so I’m playing really, really slow, and then stopping at two, every two notes—not every beat but every eighth note, actually. Because every beat would be second step, I guess. What do you think about this technique, Ausra? A: Well, I have played this sonata many years ago. I don’t think I had any problems to play it in a fast tempo. V: Mmm-hmm. A: It’s quite comfortable, actually. V: But it takes a while to get used to the melodic motives. A: That’s true, but after you get used to it, I think it will be easy to do. V: Do you think it has something to do with writing in fingering? A: Well, obviously, yes. V: I’m playing from your score, so it doesn’t have any fingering somehow. A: Really? V: Mmm-hmm. For some reason. A: Does it have any pedaling. V: No. Maybe... A: Maybe it’s not my score? V: Maybe you played from another score. A: Well… V: Could be. A: I’m not sure, but I’m not used to write every finger. V: Actually, it’s a clean score, no… A: So, so it’s not my score. V: No registration. A: It’s not my score. V: Mmm-hmm. We could ask Jeremy if he is writing in fingering in his, let’s say, Dorian Toccata that he’s playing a fugue. Or if he is actually working from our score, right? I hope so. A: Well, I think if he still has trouble with speeding up his fingering, I think he needs to play more exercises, more skills. V: Mmm-hmm. A: More arpeggios, more chords, more Hanon exercises. V: Yeah, Hanon is a nice collection, I guess. It takes in a fast tempo to play, only one hour to play, all three parts. But if you can do it then you basically can play any type of organ repertoire as well, and majority of piano repertoire too. A: Yes, because I think that being able to play up to a right speed is question of how well your technique is developed. V: Mmm-hmm. Yes. Well, what could Jeremy do besides what he’s doing? I think he’s on the right track—gradually lengthening the motives. But it takes more than one day for one stage. Let’s say step one would be to play and stop every beat, or maybe every eighth note. But it takes just more than one day, I guess, maybe three days to do this comfortably. And then second step would also take several days. Right? A: Of course! I think all of us, we want that immediate result. V: That would be nice, Ausra. A: Yes. V: What would you give if you had this ability in exchange? What would you sacrifice if you could play any type of organ music at sight, without any problem, in a concert tempo, perfectly, right now? A: Huh! V: Your pinky finger? A: No, no. But I could, I can sacrifice one of my meals today—let’s say, breakfast. V: Oh, I know why. It would actually be very healthy, too. A: Well, yes. V: But not easy to do. I would probably sacrifice my second breakfast. A: Are you having two breakfasts every morning? V: Not every day. A: Funny. V: Yeah. It’s interesting what Jeremy would sacrifice if he had this ability. A: Unfortunately, I don’t think we have such a choice, just to decide to sacrifice something and get some special quality. V: I know, like golden fish from sea would come out and say ‘I could grant you three wishes’. A: And one of your wishes would be to play any piece, at the concert tempo right away? V: Choose wisely, you say! A: Yes. V: Because only two will be left. A: That’s right. V: Hmm. A: So I guess you need to work on your pieces at your pace, as fast as you can, and don’t want to rush things right away. V: Maybe you are right, because practicing things slowly takes a lot of time, but it also gives much more satisfaction. Remember how we watch movies how we read books. Reading books is much more pleasurable, I think, than watching movies because this pleasure lasts longer. A: Well, then I wonder why are you asking me, begging me each week to go to movie. V: (Laughs.) I know. A: You never begging me to read books for example with you. V: If I did, would you read with me? A: I don’t know. V: Let’s read tonight and see if we can survive without movies—just one night. A: Yes. V: Nice! What about playing excerpts of that piece, Ausra, but exercises—maybe transposing in various keys? A: That’s a great idea. I think we have talked about it already quite a few times. If you don’t want for some reason to play additional exercises or don’t have time to do that, then you need to make exercises out from your own repertoire. V: I did once, and actually from memory. This was Magnificat Primi Toni. Magnificat by, I think Heinrich Scheidemann. A: Did it work for you? V: Absolutely. Because, you know what happened? I think practiced this piece in short excerpts—maybe one measure at at time—but went through the circle of fifths, in ascending number of accidentals, and then going back to the flat side. So what happened; I memorized this piece in fragments, and those fragments became my language too. I could actually improvise like Scheidemann sometimes. A: Excellent. V: But then, I thought, ‘well there was Schiedemann once, we don’t need the second Schiedemann, but there wasn’t any Vidas before so we need Vidas now’, right? A: That’s true. V: But it works for people who are interested in copying the style of certain composer in their improvisations. They could actually memorize just one measure and go up the ascending number of accidentals, and then going backwards through the circle of fifths. It’s really helpful. Plus it’s very healthy for technique. A: Yes, but if we are talking about Scheidemann, I don’t think he would be writing his compositions for the keys with many flats or many sharps. V: No. Because obviously… A: Not that style, not that time. V: Obviously the type of keyboard was different—it had split keys. A: Sure. V: It had mean-tone temperament so keys with more than probably two flats or sharps would sound harsh or too harsh. Right? I guess now, for just educational sake it was work right, to let’s say take Bach’s Dorian Toccata and practice fragment by fragment in various keys. Even for Jeremy it’s a good technique, especially those places which give him trouble. A: I think it might be quite beneficial. V: Should we ask him to report to us in a month or so? A: If he will do that, yes. V: Mmm-hmm. A: It would be very interesting to know how it went and if he had succeeded. V: Good! Thank you guys. This was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: We hope this was useful to you. And please keep sending us your wonderful questions. We love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice... A: Miracles happen! SOPP299: Could please talk about how to improve finger accuracy, especially with fast passages10/7/2018

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 299 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by John and he writes: “Hi Vidas and Ausra, Thank you for your amazing blogs lately, there's been some great discussions and I value the different perspectives you both bring. I'm wondering if you could please talk about how to improve finger accuracy, especially with fast passages. Specifically I'm trying to play In Dulci Jubilo BWV 729 by Bach, your training videos were great and I surprised myself how fast I was able to learn it (for me), it still took 2 months. Now my problem is trying to speed up to concert tempo. Most professional organists on YouTube seem to play this piece in 2:40-2:50 minutes, your Christmas Concert video shows you play it in about this time. I seem to be able to play it in about 3:10 mins quite ok without mistakes, but when I go faster, I seem to slur lots of notes by brushing against the key alongside, for example playing the note A I might bump the G sharp alongside. It feels like my fingers fumble, and I make mistakes in random places and even lose my place completely. This makes me feel quite uneasy and I don't have any confidence that I can get through the piece without messing it up. So I need to go about 10-20% faster and it seems a big jump in difficulty. I have noticed I struggle with fast pieces in general. Is it normal to take a long time to increase the tempo after having learnt a new piece? What exercises should I do to be able to play fast tempo pieces accurately? I want to play this piece as the postlude for the Nine Lessons and Carols service on Dec 16th, so I still have time, but this will be a big occasion with lots of people and the former retired organist will be there so I don't want to stuff it up! I hope your day goes well, Take care, God bless, John...” V: That’s a nice message. A: Yes, that’s a very nice message as John always writes to us. Well, let’s try to help him. V: OK. In Dulci Jubilo the most characteristic thing is probably passages in the upper part. Sometimes they run in soprano but sometimes they go between both hands and Bach learned this technique presumably from visiting Buxtehude in Lubeck. A: Yes. V: I think the main difficulty with those passages is 3 sharps of course. It’s in A Major. A: So what we could suggest for John if he has the possibility to practice those scales. V: Right. A: I would work on scales in A Major. V: A Major. Probably in related keys as well because Bach has modulation. A: In D Major probably, E Major. V: F Sharp Minor. A: F Sharp Minor yes, it’s a parallel key. V: And C Sharp Minor maybe. A: True. In general I think playing scales is important technique to develop and it helps a lot when playing repertoire. V: B Minor too because it has 2 sharps. So playing scales and arpeggios too because these passages have arpeggiated figures as well. Maybe we could suggest to John to isolate one passage and look how it is put together and maybe transpose it to different keys. The only passage, nothing more, just the passage. Would that work? A: Well that might work but in general I think he needs to strengthen his finger muscles. V: Oh, so Hanon exercises. A: Yes Hanon exercises would be another resource to look at and to work on. But overall I think that you don’t have to look at other performers and compare your tempo with another. Because the most important thing is that you wouldn’t take too fast tempo. You need to take tempo as fast as you can still control everything because otherwise that freedom is OK for now. Maybe you will speed it up a little bit but don’t rush. V: And maybe when John comes back to this piece maybe couple years later he can play without any trouble in less than three minutes. A: That’s right. So I think listeners will forgive you if you will not play very fast but they will not forgive you if you mess up everything even if you play it fast. V: One or two mistakes is OK obviously but in things like that we tend to get scared of mistakes and one mistake leads to another and another to another and pretty soon we panic. A: That’s right. And for listeners it’s so uncomfortable to listen to such a performance because you know that you are not guilty of something but you feel that way. V: Umm-hmm. You feel sorry for that organist and sort of helpless because you can’t jump in and play for him. A: That’s right. So I always think you need to take a tempo in which you can control the situation because otherwise things might just get out of your control. V: So probably the most beneficial would be Part 1 and Part 2 Hanon exercises and he could stack up maybe ten to twenty exercises in a row. Maybe not necessarily learning all of them together but maybe one day he would learn number one and then repeat a few days, after a while he would add number two so then he would have two exercises in his repertoire, three, four, five, and I don’t know in three months he would have maybe entire first part ready to play in a medium tempo and then his hands get tired, his fingers would get tired too, but sooner or later they would be stronger. A: That’s right and it’s very good to practice on the piano too. Because in order to improve your technique you need to practice mechanical instruments, either mechanical organ or mechanical piano because electronic keyboard does not give for you enough for your fingers to work on. V: Resistance? A: Yes. V: Some very new keyboards they have this artificial resistance which is similar to real organ but not many people play them. A: True. V: So I guess I could also recommend playing on a table just mechanically lifting and hitting the table with fingers those exercises because it’s a pain to listen to them, right, for the family for example. They are very un-musical and boring unless he takes different modes and adds some sharps, not only in C Major. OK guys, please send us more of your questions, we love helping you grow. This was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: And remember when you practice… A: Miracles happen. By Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene (get free updates of new posts here)

Have you met an organist, who thinks that unless an organ has 3 manuals and pedals, it's not worth their attention? There are many people like that, actually. When they sit down at the simple one manual organ, they don't know what to play. "You can't play Reger on it", they say. Which is correct, if you try to find an organ suited for your own needs and repertoire. But what if the opposite is actually more true? What if we need to find a repertoire that suits the organ? This attitude would change things around, wouldn't it? So if you sit on the bench of one manual instrument, think about how many stops does it have. Let's say it has 8 stops. In reality, it could give you 64 different combinations of colors (8 x 8 = 64). Some of them more unusual than others for sure. If you play just one minute on each stop or combination, you would need 64 minutes. A hymn with 64 variations? Or 8 hymns with 8 variations each? That's plenty for an entire recital. In my yesterday's post How to play marches on manuals only I proposed the following way to play marches on manuals - in places with pedals, assign three voices for the right hand and one for the left hand. This disposition will be similar to basic basso continuo (thorough bass) performance practice where you play three upper parts with the right hand.

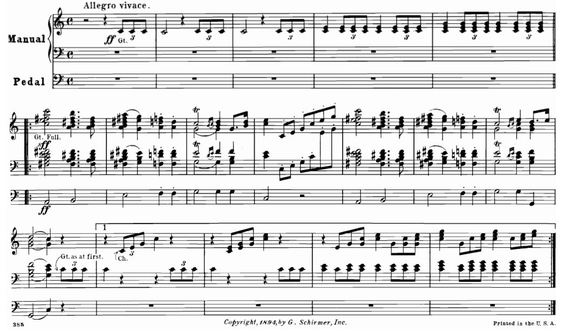

In doing so these chords sound in closed position as opposed to the version when you place two voices in each hand (often this means open position). Therefore, this technique will help you preserve the original harmony while making your marches playable on the organs and keyboards of all sorts without pedals. In response to this post, Oswin Grollmuss asks if in this way there might be an artistically responsible interpretation of the March in C major of Léfébure-Wely as well? Could this be a technique to transfer other pedal pieces to manuals only? In other words, can you take any organ piece with pedals and in the event you don't have pedals at your disposal, could the result of this piece played on manual only would still be meaningful? I don't think this March can easily be played without the pedals. More than that, it needs two manuals - because right from the beginning there is a melody in the tenor range which sounds on the solo reed stop. The problem with other pedal pieces played in this way on manuals only is that often their are quite polyphonic and this technique works only in homophonic chordal texture. In polyphonic style, several voices form a coherent musical image. You can't really exclude any voice and you can't successfully transfer tenor one octave higher. In general, the technique of playing one voice in the left hand and three in the right hand works for organ arrangements of orchestral or piano music. And it has to have a strong melody in the top voice. Having said that, you could experiment with this March by playing the beginning melody in the soprano with the right hand one octave higher, the bass and chords in the left hand. Play the chords one octave lower. But if you really want to play original pedal pieces without pedals, find a partner and play them with four hands. This is both fun and easy - you can play the entire Bach's Orgelbuchlein this way - two parts (one in each hand) for each of you. I have done this together with my wife Ausra when we play organ duets in some remote village church on the small organ without pedals and we still want the listeners to appreciate the beauty of Bach's Aria in D major, for example. Sight reading for today: Grand Plein Jeu Continu (p. 1) by Jacques Boyvin (1649-1706), a French Classical organist at Rouen Cathedral and composer from his Premier Livre d'Orgue (1689). Grand Plein Jeu registration in French tradition basically means a 16' based principal chorus with mixtures as opposed to Grand Jeux which is meant to play with Cornets, Trompettes, and Flutes without the 16' stops. The indication of pedals at the beginning here comes from the editor Alexander Guilmant. Yesterday one of my subscribers, Dr. Steven Monrotus wrote me a following message:

"Thank you for sending the valuable suggestions and public domain scores for performance, they're helping a great deal. Could you please suggest marches for manuals only. At times I perform on an instrument without pedals where marches and processionals are needed with full sound, sometimes for long stretches without a pause. Any suggestions or scores you could send would be very much appreciated. Thank you very much." It's great that people like Steven are finding at least some usefulness to these ideas and scores for sight-reading. Many of them are church organists who may or may not have an organ with pedals in their churches. That's a bit of a problem when it comes to wedding services. You see, for regular church service on Sunday you can easily find quality and playable repertoire (much of which is for manuals only). But for weddings when you play an instrument without pedals, you need to take a more careful look at what's available. One idea which I often find useful when I have to play a pedal piece on one manual is to experiment with outer voices only - soprano in the right hand and the bass (pedal part) in the left hand. Because these two voices often are the most important ones in the piece, there are instances where it works beautifully (Bach's Largo and Aria in D major for example). I played this march this way (the original is for the orchestra: Jean-Baptiste Lully - Marche pour la cérémonie des Turcs (Le bourgeois gentilhomme), especially from 1:52 in this video). If you're looking for marches without pedals, then Guilmant's "Practical Organist" first comes to mind. Besides marches, there you will find fine short compositions suitable for liturgical organ playing, such as communions, versets, offertories, postludes etc. Every piece is skillfully composed and could also be used for recitals. It's perfect as a preparation for more advanced organ sonatas by Guilmant. Also The Oxford Book of Wedding Music for Manuals is an authoritative collection which might be worth considering, too. For those of you who already have the famous marches in their collections but they need pedals to be performed on the organ: Can you still play them from the original organ scores? The answer is yes, if you could do the following trick. In places with pedals, assign three voices for the right hand and one for the left hand. This disposition will be similar to basic basso continuo (thorough bass) performance practice where you play three upper parts with the right hand. In doing so these chords sound in closed position as opposed to the version when you place two voices in each hand (often this means open position). What does this theoretical rule mean in practice? When you have to play Mendelssohn's Wedding March (p. 47) for a wedding, play the bass line with the left and the top voice with the right hand. Then for the same right hand add the missing two middle voices in closed position. Basically this will allow you to avoid unnecessary doublings of voices which are common for thick chords played by both hands. Therefore, this technique will help you preserve the original harmony while making it playable on the organs and keyboards of all sorts without pedals. Sight-reading for today: Das ferne Land, Op.26 (Distand Land) by Adolf von Henselt (1814-1889), a German composer and pianist. This piece is a romance for voice and piano but here you can practice an organ arrangement by W.J.D. Leavitt. |

DON'T MISS A THING! FREE UPDATES BY EMAIL.Thank you!You have successfully joined our subscriber list.  Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas

Authors

Drs. Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene Organists of Vilnius University , creators of Secrets of Organ Playing. Our Hauptwerk Setup:

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

This site participates in the Amazon, Thomann and other affiliate programs, the proceeds of which keep it free for anyone to read.

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed