|

Vidas: Hi guys! This is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 547 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by J. Flemming. He writes, Although my teachers have stressed the importance of articulate legato in playing Baroque music, I was never taught early fingering, so it is very easy for me to lapse into familiar patterns (like crossing my thumb underneath my fingers). I am learning BWV 659 (ornamented chorale Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland) with Vidas’ fingering, and it is taking more repetitions to get used to the fingering. The results will be worth it, though. I expect to be able to play this in a service before Advent is over. It’s been a good exercise in developing the discipline to do it right instead of quickly. So, this question was sent before Advent was over, obviously. A: Sure. V: And now we’re talking after Christmas. Okay, it’s very nice that J. Flemming is using my practice score of Nun komm der Heiden Heiland. In this particular score, I really take advantage of early fingering in the left hand, where you have two voices, alto and tenor voices combined. And also, in the soprano part, where there is one ornamented, highly ornamented melodic line. And in the pedals as well, even though they move slowly, I don’t use heels, I don’t use substitutions, in the hands also, no substitutions, and no thumb glissandos, things like that. A: You don’t need glissandos, because you play everything in detached manner, articulate legato, so… V: At first, it sounds strange, right, Ausra? A: What? V: This type of articulation. Or not? When you first started, what was your experience with articulate legato? A: Actually, it was like discovering America for me. Because here nothing sounded swell while playing baroque music, and sort of half-articulate way or legato way. Because instrument itself wouldn’t speak if you would play legato. V: Mm hm. For me, I couldn’t discover this articulation for a long time. Even though my first teacher sort of taught me this. But, it was very complex explanation. I couldn’t get the basics right. And plus, of course I was very young, and you had to understand something differently. A: I don’t think your first teacher understood the manner of articulation very well, too. Even in the Academy of Music, there was none that taught articulation really well. We had some sort of understanding about it, but incomplete and insufficient. And incorrect in many ways. Because if you would look at the Academy of Music at all our professors, and you would look how we play the pedals, how we are pedaling Bach, it’s just horrible. Remember when we went to Eastern Michigan University, and our professor, Pamela Reuter-Feenstra, saw our score that we brought from Lithuania, and it was with the fingering and pedaling, by your professor, Leopoldas Digrys, she just thought to throw that score away right away and never come back to it. V: Or put it into a museum of incorrect fingering! A: Yes. So, basically, so I guess the right understanding of why this articulate legato and fingering and pedaling is needed, came to me when I tried, basically historical instruments, and especially the pedal clavichord. V: Yeah, instruments themselves can teach you a lot. Probably more than any teacher can. Although, I understood the basic articulate legato principle easier, I think when I started studying fromRitchie/Stauffer method book. Because he gives this exercise to play with one finger, as legato as possible. But since you are only playing just with one finger, it’s not really legato. And then repeating the same articulation with all the fingers. Sort of imitating. And then it clicked for me. All the voices have to play this way, even though you are using all the fingers. But if you are not sure, play with one finger only at first. A: But developing this technique, it takes time and patience, of course, too. I think every time when you practice organ, you need to have patience and you really need to listen to what you are doing very carefully. Because it’s basically an art to be able to play baroque, romantic, and modern music, especially if you have to do that all in one recital. V: And if you’re a beginner, those three styles can mix in your head, right? But it’s very, I think healthy to work simultaneously in three different styles: early music, romantic music, and modern music. Because the more you do it, the more easily you can switch between them. A: Sure. V: Right? A: That’s right. V: And the longer you play with one style, the more difficult it is for you to switch, right? Especially if you are a beginner. You get used to one particular style. Let’s say you’re playing Bach chorales all the time. Or let’s say short preludes and fugues, from the famous Eight Preludes and Fugues collection. And you don’t play anything else, and if you suddenly start playing a romantic piece or a modern piece, it doesn’t feel natural, right? A: Sure. V: You have to switch, like between having three different cars, or five different cars, or twenty cars...the more the better! A: I would say it’s probably not switching a car, but like switching from a shift stick to the automatic. V: But cars are also different between themselves, between mechanical and mechanical - different models, right? So how your foot feels on the pedal is different. The wheel also is different. And the gears shift differently a little bit in each car. But car mechanics don’t have any trouble because they have tried them all. A: Yeah. V: Ok guys, this was Vidas A: And Ausra. V: Please send us more of your questions. We love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice, A: Miracles happen.

Comments

SOPP397: I have purchased several of your fingerings of old music and find them extremely useful2/16/2019

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 397 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Rob and he writes: Dear Vidas and Ausra, I have purchased several of your fingerings of old music and find them extremely useful. When I learned to play the organ in the 60s, I was taught a legato style that, for example, discouraged using the same finger consecutively for different notes. It’s liberating to see you doing this all the time, and your method makes my playing feel more natural and more musical. I have two questions. First, is your fingering method standard for 16th-18th c. organ music or is it to some extent personal? Would you and Ausra, for example, come up with essentially the same fingering for any given early piece? Second, following on from that, how important do you think it is for a student to stick closely to your fingerings? Right now I’m learning Bach’s Passacaglia with your fingerings and I like them a lot. But occasionally they lead to my making mistakes that I wouldn't ordinarily make using a more modern style. For example, in mm. 204-7 during the fugue, the left hand has a pattern of arpeggiated 16th notes at intervals of a third, with three descending groups per measure. You finger all three groups 4-2, 4-2, 4-2, which I find hard to play without hitting wrong notes and becoming choppy. It’s much easier for me to use 2-1, 4-2, 5-3. In a case like this, would you recommend that someone try to master your fingerings, as being more authentic and conducive to a better interpretation in the long run, or is it legitimate to adapt them to one’s personal comfort? With thanks and best wishes to you both, Rob V: That’s a very thoughtful response Rob gave us right Ausra? A: Yes, it’s a very nice letter. Answering Rob’s question this fingering that we create, Rob asked if Vidas fingering and my fingering would be exactly the same for the same piece. V: You say it would be exactly the same. A: Well, it would be very similar. That’s what I want to say, that it would be very similar. Maybe they could be different in some particular spots. There might be slight differences but in general I think it would be almost the same or very similar. V: Even though our personalities are different our fingerings are similar. A: Yes, because that’s what baroque music requires and yes, this type of fingering is suited for pieces written between the sixteenth through eighteenth century. Of course you know the more complex music is, Bach for example, the more new ways you have to introduce into your fingering. V: Modern fingering. A: Yes. V: But still avoid finger substitution I think. A: Yes and sometimes if you find a spot which is completely difficult for you to play you might do slight adjustments. About that particular spot in the Passacaglia I think what Vidas meant by making those groups 4-2, 4-2, 4-2 it is that the same intervals are played with the same fingers. In that time it was sort of like a general knowledge because it helps you to articulate because why we need this fingering in order to make Baroque music sound like Baroque music it’s just all based on articulating each note and you could get exactly the same effect with playing and using modern fingering but then you would really have to control yourself very hardly in each measure, in each note. V: Umm-hmm. A: When you are using early fingering then it helps you to do articulation without so much thinking about it. It becomes more natural. V: Yes. A: I don’t know if it makes sense. You can continue my talk. Do you agree? V: I’m looking at this passage in Passacaglia where there are sixteenth note triplets and I write 2-3-4, 2-3-4, 2-3-4. I think this is the spot that Rob refers to because we don’t have measure numbers. A: But it seems like that spot, yes. V: Umm-hmm. The reason I do 2-3-4 is to avoid using the thumb on the sharp keys of the flat keys but in fast tempo you need to be very precise and it’s not very easy. A: And also because you start each triplet with the same finger you have of course to articulate there too. V: Maybe Rob could try the trick that I think is applicable to all organ music in general. Not to lift the fingers off the keyboard. Basically keep them in contact with the keys at all times and therefore the movements will be more economical and maybe more precise, right? What do you think Ausra here? A: Yes, I couldn’t agree more but actually in this spot, yes I would exactly the same fingering that you wrote in. V: Umm-hmm. 2-3-4, 2-3-4, 2-3-4 for the right hand ascending or for the left-hand descending and vice versa. 4-3-2, 4-3-2, 4-3-2 for the right hand descending and left hand ascending. That’s kind of natural to me but if Rob has trouble I think it’s appropriate to change some things to their own hand position but try to avoid finger substitutions, that’s my point. As you said with Bach you can add more modern fingering because he using modern keys and modern figures but still… A: And textures, you need to use almost all fingers at the same time. V: But most of the time you could get away without finger substitutions, most of the time. A: That’s right. Finger substitution in general is not a good thing in Baroque music. V: I have encountered a few places even in Bach where you had to use finger substitution because the texture as you say was like maybe five voices in the hands at the end of the piece you know, not in the middle… A: In cadences where he adds extra voices. V: Then yes but that’s an exception I would think. A: Sure, that’s not a rule. V: Excellent, so that’s the second part of Rob’s question. The first part of his question asks us about if we would use the same fingering for any early piece. I would just add that it depends on the school of composition. The geographical area basically. If it’s Spanish it’s one way, German it’s a little bit different, Italian different, French also should be different because ornaments are different and strong fingers are different. In one area they used 2 and 3 as the stronger fingers and in the left hand they also used 2 and 3. A: But sometimes 2 and 1. V: 2 and 1. A: And actually if you are interested you could study some of iconography related to portative organ. It was very common to paint either Saint Cecelia or angels playing portative organs and sometimes you can see hands very closely and you can even figure out what fingers angel or Saint Cecelia used and it’s a bizarre looking thing. V: I wonder how come there is no iconography of piglets and hedgehogs playing portative organs? A: Probably we never did. V: Maybe they don’t have enough fingers. A: Yes, if you are a pig you only have two fingers so not much of a choice. So natural pair fingering. V: Right. 2 and 3 or 2 and 4. Wonderful guys, please send us your wonderful questions in the future. We love helping you grow. And remember when you practice… A: Miracles happen.

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 375 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Howard and he writes: “Hello Vidas, Happy New Year, and I am wishing you all the best for Total Organist in 2019. I noticed and appreciate the program you did on piston programming for larger modern organs. I have another question inspired by today's topic on "I cannot use someone else's fingerings". This is EXACTLY my problem that is holding me back from becoming a full subscriber to "Total Organist". But my question is more direct and I am hoping you will consider it as a program topic or as a direct answer to me, your choice :-) Basically, as I understand it, the fingerings for Early Music which, to be honest, is 90% of the material that you offer for study, those fingerings are for baroque style keyboards which are much shorter than AGO spec keyboards. I am wondering why the focus on using fingerings inspired by these older keyboards? I'd say that 99% (seriously) of the music that I own does not have fingerings. One of the exceptions is a Kalmus edition of several Mendelssohn works including all six Sonatas. I've spent the most time with Sonata #4 in Bb. The fingerings suggested and the fingerings that make sense to me are not even from the same planet! Especially the 3rd movement. The way the Kalmus editor fingered it, the running figure in the left hand is entirely independent from the right hand. Completely. I've worked very hard on doing it this way but my natural inclination is to pass notes back and forth between the hands and I can do this and still preserve the independence of the polyphony. I know that you have fingered the Widor Toccata and a few other modern works, and I am assuming you use 'modern fingerings' for those, but I can't help but wonder why you don't just make life easier for yourselves and use modern fingering for everything? Is there really something to be gained by using Early Fingering at all in the 21st Century, especially for Bach who, it must be said, transcended his time period. And here is one more idea for a program topic that you may (or not) want to touch ... two years ago on my way to church, I had a hard fall onto my left side. When I got up I realized I had bashed my left hand and my pinky finger was bleeding slightly. I was playing the "Cortege et Litanie" that Sunday. I thought I was just a little sore and could play through it, but ever since then the pinky and ring finger of my left hand refuse to open fully. Only a very, very few people know this. My employers do not know. I can still play most things as before, but the big stretch near the beginning of "Cortege et Litanie" is impossible. Scalic passages that should naturally begin with the left hand pinky or ring finger are extremely hard now and often don't work. To be honest it has affected my typing much more than my organ playing. I used to be a terrific typist but now the left hand keys are impaired. I am terrified of having surgery done because of a.) the potential downtime and impact on work, and b.) the potential for success of such surgery. I did see an occupational therapist and had several weeks of various stretching exercises that produced no results. I have recently heard of a colleague who seems to have a similar injury except his has no known cause. He has stepped down from playing but his church is still paying him to be a Music Director. I have another acquaintance with a similar problem (Dupytrenes Contracture) and has had two unsuccessful hand surgeries. My hand therapist didn't even know what to call my injury. She just say's "its weird". That wasn't encouraging so I stopped going to appointments. I am beginning to wonder about why this has happened because more recently, about 3 months ago, I had someone crush my hand in a handshake. All the fingers of my right hand have recovered fully except the ring finger which is trying to act like the one on the left hand. I knew of musicians who refused to shake hands but I've never thought I was worthy of that kind of concern. My attainments have been so humble. Do you have any experience with occupational injuries and what musicians do about them? There you have it. More than you wanted to know about my travails, but I don't have anyone else I can tell. Anyway, don't think about this too much. I am working. I am not suicidal. I'm just wondering if there is more I could do. Or what someone else might do in the same situation. Be well. Howard” V: That’s a long story Ausra. A: It is. V: Let’s start with occupational hazards and probably a person like Howard should consult many different or several different physicians. A: You know if I would be a very mean person I could make a very bad joke about his question because I could relate the second part with the first part. V: Uh-huh. A: Because when you were reading that first part it just took my breath away and I could tell that all these professional injuries happens because of not playing let’s say baroque music with early fingering. But that’s just a really bad joke. I think there is connection in everything that we do. V: But don’t you think that if his therapist doesn’t even know what to call his injury probably she is not the person to help him. A: Yes, it seems to me that he has to change his doctor. V: And probably go to several different people to check their opinions and sooner or later, maybe sooner than later he will find a person who will know what to do in his situation, what caused this, and how to treat it. A: But in general I think that every person has sort of limitation of the joints and of the fingers and probably there is a limit of movements you can make in your lifetime, maybe for some it’s I don’t know. Hundreds of millions of movements and for somebody maybe it’s less than that. Maybe he is having overused syndrome. V: I wonder if he’s wearing any rings on his fingers. A: I don’t know but rings are bad actually. V: Umm-hmm. A: In most of cases for musicians I wouldn’t wear rings. But if such an action as shaking the hand might hurt his hands, that is really bad. That just shows that something is really wrong with his hands and that he needs serious attention from a good physician. V: Exactly. So talking about the first part it’s a little bit easier, right? A: Well I wouldn’t want to go into those details because I think I have talked about it many times and I think everybody who listened to my talk knows my opinion about how I feel about playing baroque music. Well, I guess if I would live all my life somewhere in the United States where I would not have an access to the historical based instruments although there are places that you can do that in the United States as well, let’s see, in Oberlin, in Omaha at St. Cecelia’s Cathedral and there are other wonderful places where you could go to try those wonderful instruments. I will just try to give one example with the food. Imagine that you have let’s say cheeseburger from MacDonald’s and cola and you wonderful nice French meal with good wine. They both are food, yes? And you would satisfy your hunger maybe with eating both of them, but in terms of quality would you still disagree that French meal is better and has a higher value? V: Umm-hmm. Obviously the answer is very clear. A: And I don’t know but maybe somebody with fast food would still agree with me but… V: In which sense are you comparing modern fingerings with fast food, can you clarify? A: Well I’m just talking that early fingering does not work for late pieces, romantic and later period but that modern fingering doesn’t work for early music and it seems like Howard is not very happy that we deal so much with early music but let’s face it, Bach is the main composer for the organ. I doubt that anybody would argue that so come on, Bach wrote his music in the baroque period. V: I would add that the reason that we are using early fingerings for early music is that it makes sense because it’s early music. You don’t know if you will have a chance to visit an early instrument. A: And even if you don’t have a chance, even if you are playing on American modern instrument you still need to articulate so it still makes sense to use early fingering. V: When you use modern fingering you have to think about articulation mentally and when you are thinking you are missing something probably in the middle voices, in the pedals too. You maybe aware of some significant details but not everything when you on the contrary are using early fingerings it takes care for itself, right? For example, a simple fact that the same intervals as a rule are played by the same fingers. For example, an interval of the sixth can easily be played by the fingers 1 and 5 and if you have parallel sixths you play 1,5, 1,5, 1,5 and so forth. It seems detached and unmusical but we are not advocating for playing unmusically. We are recommending to play those intervals as slurred as possible but not legato. That’s in between of legato and non-legato in a singing manner which Bach would call cantabile manner of playing. Would you agree? A: Yes, because if you are professional you need to notice those subtle things that might not be understood by amateurs and if we would tell you just play whatever and play however you want we wouldn’t be professionals so we teach what we believe in. But it’s up to you to choose believe us or not and you do whatever you want to do. V: And there are people who play early music with modern fingerings and if Howard would rather play early music with modern fingerings then probably he would find more benefits from studying with them, right? A: Sure, of course. V: That’s simple. We are not trying to convert people who do not believe what we say, right? Everybody has their own choices and preferences and people like us tend to stick in our circle, right? A: That’s right. V: People who trust us, right? That’s very simple. So that’s a lot to think about but obviously fingerings are just a simple detail but I worry about Howard’s hands so he should really seek out several physicians and get several opinions of his hands what’s happening. A: But actually nowadays many people get that wrist surgery because of problems similar to Howard’s and not only musicians but also people who work on the computer a lot too. So you are not alone. V: Exactly. Thank you guys, I hope this was useful and please send us more of your questions, we love helping you grow. And remember when you practice… A: Miracles happen.

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

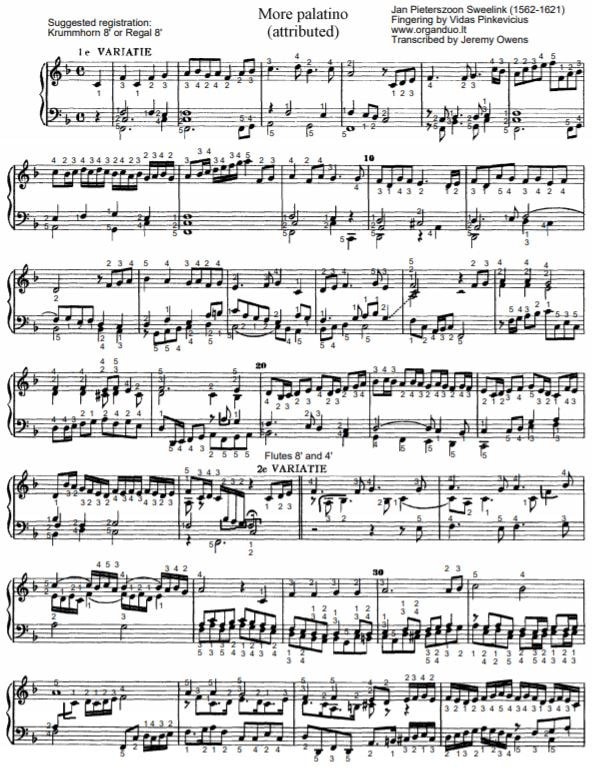

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 333, of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Lukasz. And he starts with his questions, with a quote from our previous podcast conversation about performing the Dorian Toccata by Bach, where Ausra, says: ..."A: Well, unless you would use the 5th and 4th finger to make the trill. V: “Oh, that’s...that’s torture!” A: “It is! Or maybe you could play those 16th notes with your left hand"… So Lukasz later writes: I think it is not a torture, it is a necessity for Bach. Try to play Goldberg's without 5th and 4th trills in right ... and left hand... agree, at start it is difficult, but for Bach - in my opinion - necessary, same like playing parallel sixths legato in one hand - same right and left hand. I also considered these things as too difficult, something just from art of circus and not really needed for organ. Until the time I've start to work with Goldberg's variations—which I loved and when I started to play it I went crazy about it. But by the way, it completely overturned my manual technique. More—I practiced it on SINGLE!!! manual organ!!! Yes—I have been working on them for a long time, I will say honestly, I will work on them until the end of my life. (By the way, many musicians - including Glenn Gould - say and I confirm it—that as you start to play Goldberg Variations—it will stay with you for the rest of your life.) This is really amazing music—not just for listening—but especially for playing. It changes a lot—also playing the ornaments and long trills by 4 and 5 fingers appears to be not a torture :) Have a nice weekend Lukasz A: You know what I suggest to Lukasz to do? To come to St. John’s church in Vilnius and try to play a trill with 5th and 4th finger and I am probably sure that he would just break his two fingers, and he could not perform at all. And another thought that I thought about while reading his question was that Goldberg variations really doesn’t work for organ. Definitely it’s a piece that should be played on the harpsichord, and I’m positive about it. V: Right. A: So, and another thing, Glen Gould of course that wonderful performance of Glen Gould and all his Bach performance, but I don’t like his Bach’s recordings so well. So, that’s a matter of taste. And now I let you to talk about what you think about it. V: Uh-huh. I would recommend, when you say for Lukasz to come to our church to play, but not only to play in general, but to play the trill between E and F in the first manual. A: (Laughs). Then you really would die. V: Between the 4th and the 5th finger. A: You would break them—that’s for sure. V: Right. That’s question. Because those two keys are stuck a little bit inside of the action, and I cannot reach it. I have to get some big, professional help, and I haven’t gotten it yet. So, those two keys are more difficult to depress than others, and other keys are not easy to depress also, So… A: True. V: So in general, it’s really difficult instrument. A: Well for example, if you are playing Goldberg’s variation, that actually I had played this piece while working on my doctorate at Lincoln, because I was taking harpsichord all the years that I studyed in the United States. So, yes. On the harpsichord, to play trills with the 4th and 5th finger is very easy… V: Mmm-mmm. A: ...and really comfortable. So, it depends on which keys you are playing on. V: It’s comfortable to play on the third manual of St. John’s church too. A: Yes. V: It’s easy enough. Mmm-hmm. So maybe things can get adjusted because we have three manuals and in Goldberg’s variations, he usually needs two. And not in all the variations. So you can jump from manual to manual sometimes, and play on two manuals. A: But I would really leave this piece for the harpsichord because it doesn’t have the pedal. And to play such a massive piece, really, is one of the most powerful piece that is written by J. S. Bach, and to play it on the organ and not use pedal, it just doesn’t seem worthwhile. V: What about The Art of Fugue? It’s also seem to playable on the harpsichord and we heard it played by Peter Dixon. And it could be played with the pedal on the organ too. A: Well, that’s another story. I like it both ways. V: Mmm-hmm. A: That fugue. That same thing—it works well on both instruments, but not Goldberg’s variations. V: Mmm-hmm. And Glen Gould seems to… A: He did it on the piano. V: ...on the piano, with one manual. Or are there any two manual pianos around? A: I don’t know about all kinds of experimental instruments. V: I’m quite sure that somewhere there would be even three manuals. A: Sure you could find anywhere, nowadays, yes. V: Yes. But, and I remembered to an instrument museum in Vermillion and we saw some strange keyboard layout, with eighteen keys per octave or something, and it’s very strange… A: True. V: ...disposition. A: More like experimental keyboards. V: You need to spend like three years while learning to play such an instrument and then you will have a hard time playing the normal instrument. A: That’s right. V: Right? So, do you think that strong 4th and 5th finger is a good help for an organist? A: Yes, it is. V: Mmm-hmm. A: Definitely, it is. V: Mmm-hmm. Our conversation is not to prove that we don’t consider it’s importance for organists, right? Definitely try to strengthen your little finger and the fourth finger, on both hands, also. A: Yes. V: Mmm-hmm. A: For me, it’s just amazing that somebody just picks up on one line and tries to make the whole story out of it. V: Mmm-hmm. A: Taking it out of the context, from the context. V: Maybe because that resonated to him a lot, because he… You know this, when you listen to some conversation or read an article, and suddenly a paragraph or two lines stick to you because you have personal experience about that line, so that’s what happened I think. A: True. V: Good! And then, what kind of exercises could you suggest, Ausra, to strengthen 4th and 5th finger? Or are there any in your baggage of tricks, that you use everyday, before breakfast? A: Well, (laughs) you know, you got me. Do you have any special exercises? V: For a 4th and the 5th finger? A: Yes. I think actually that... V: Sure. Hanon A: Hanon, yes. V: The, even the first part, which is relatively easy, works on those two fingers also sometimes. Because, unless you strengthen those fingers, you cannot proceed to the second part. And unless those strengthen those fingers even more, you cannot proceed to the third part. So I guess for people who are interested in strengthening all fingers, and especially those weak fingers, could take a look at all three parts of Hanon, Pianist Virtuoso. A: Yes, and now I thought that I will definitely draw a comics about this thing—playing trills with the 4th and 5th finger. V: Interesting. A: And since my main hero of the comic is a pig (laughs), which surely has what? V: Two. A: Two. V: Fingers. Long and short, or short and long. A: So, it will be fun. V: Mmm-hmm. And the second hero character is what? Hedgehog! A: That’s right. V: How many fingers does he have? A: I don’t know, maybe four. V: When I draw Spikey the hedgehog, I don’t draw fingers at all, just little paws. So it wold be like... A: So you can play it still with both paws… V: Uh-huh. A: Simultaneously. V: Mmm-hmm. Yeah. We will definitely post some visual material for you too. Because some of those comics are quite funny, we hear from our readers, from other blogs that we write. But not for organists. Sometimes you might get amused also. A: True. True. V: Alright, guys. Thank you so much for staying with us through those difficult, sometimes, conversations. And we hope you get things that are useful to you. Obviously Lukasz got interesting things from the previous conversation when he was quoting us. And that resonated with him and he produced a nice question. So please keep sending us your thoughtful questions. And we love helping you grow. This was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: And remember, when you practice... A: Miracles happen! These 4 delightful variations of More Palatino originally were attributed to Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck.

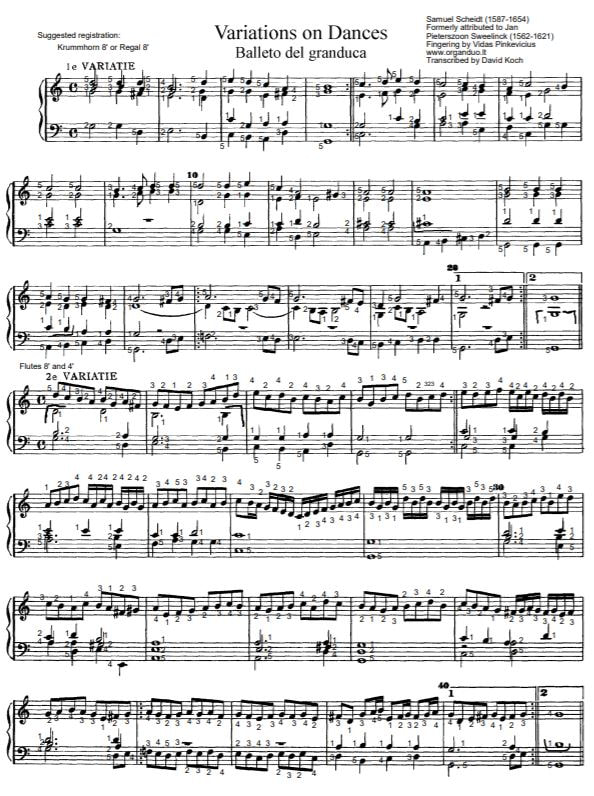

I have created this score with the hope that it will help my students who love early music to recreate articulate legato style automatically, almost without thinking. Thanks to Jeremy Owens for his meticulous transcription of fingering from the slow motion videos. If you liked Baletto del Granduca, I'm sure you'll love More Palatino too. Check it out here Intermediate level. Manuals only. PDF score. 3 pages. 50% discount is valid until March 16. This score is free for Total Organist students. These delightful variations of Balleto del Granduca originally were attributed to Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck but recent scholarship points to Samuel Scheidt as a composer.

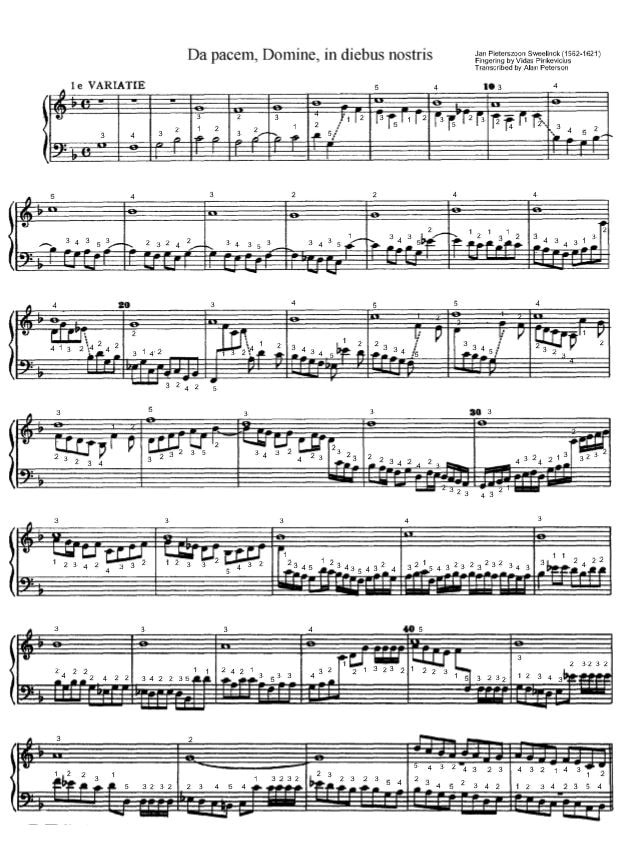

I have created this score with the hope that it will help my students who love early music to recreate articulate legato style automatically, almost without thinking. Thanks to David Koch for his meticulous transcription of fingering from the slow motion videos. Intermediate level. Manuals only. PDF score. 3 pages. Check it out here 50% discount is valid until February 8. This score is free for Total Organist students. Would you like to learn Da Pacem, Domine, in diebus nostris by the great Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck (1562-1621)?

If so, this score is for you because it will save you many hours of frustration. I have created early fingering for every single note which will allow you to achieve articulate legato automatically, almost without thinking. This set consists of 4 variations (manualiter only, no pedals): Variation 1: Bicinium with the chorale melody (cantus firmus) in the soprano Variation 2: Trio with the chorale melody in the tenor Variation 3: Quartet with the chorale melody in the alto Variation 4: Quartet with the chorale melody in the bass Note that these four settings are perfect example for anybody wants to creatively play hymn accompaniments. You too, can create duets, trios, and quartets from any hymn tune and place the melody in ANY voice. Thanks to Alan who meticulously transcribed the fingering from my videos. 50% discount is valid until February 5. Check out this score here Intermediate level. PDF score (4 pages). This score is free for Total Organist students.

Vidas: Let’s start Episode 108 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. This question was sent by Andrew, and he writes:

“Dear Vidas, thank you for your email particularly since you must be very busy judging by all your posts! In reply to your question, I’m currently working on Franck's Final, and hoping to move on to Stanford’s “Rheims” from the second organ sonata, hopefully in time for Armistice Day 2018.. I visited Rheims last year. What do I struggle with? Early fingering and ornamentation, particularly making Early English music sound coherent and fluid. Andrew” So, early English music--that’s probably John Bull, Orlando Gibbons. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: Redford, Tallis... Ausra: William Byrd... Vidas: Byrd, yes. These things. Basically… Fitzwilliam collection. The collection is enormous--it has 2 gigantic volumes-- Ausra: Wonderful collection, yes. Vidas: And I don’t even know how many hundreds of pieces there are from the time of before Purcell, I think--16th century, end of 16th century, late Renaissance; right, Ausra? Ausra: Yes. And I think this collection also includes music by Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck. Vidas: Yes. Ausra: The only one, I think, non-English composer. Vidas: Exactly. So, all those wonderful English composers have a lot of passage work and runs with each hand sometimes, and many many ornamentation instances. Ausra: Yes, you have to be a virtuoso to be able to play these pieces. But there is also a good side about this music: it almost doesn’t have pedal. So you can play it not only on the organ, but also on the harpsichord, and also on the clavichord or virginal. Vidas: Exactly. A virginal is a smaller version of the harpsichord, like a spinet, sort of. Ausra: Yes, it’s really small. Tiny. Vidas: And it works well on the organ, too, I would say. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: I played, a few years ago, in our long recital based on this collection which was devoted to English composers, and I sort of liked it, because then of course, I had to figure out my registration, because it’s not written in the score (because it’s really not for the organ); but I had some imagination with this, and our church organ at Vilnius University St. John’s Church was quite colorful. Ausra: Yes, and what actually helped me to be able to play early music better was the clavichord. Actually, basically the clavichord was the instrument that showed me, really, how to play early music well. Vidas: What’s so unique about the clavichord, Ausra? Ausra: Well, it’s sort of an instrument that teaches you. Teaches you to use correct fingering, then to use the right touch on the keyboard. And if you would be able to play a piece of music on the clavichord well, it will sound good on the organ, too. Vidas: Historical clavichords have shorter keys and very narrow keys; and the touch is so light. And it seems like it’s very easy to play; but it’s not, because you have to use all the big muscles of your back, basically, to give some weight on the keys. Ausra: Yes, yes. And because it’s different from the organ and harpsichord. Because on the organ or harpsichord you can make the sound louder or softer only by adding or omitting stops; but while playing clavichord, you can do actual dynamics just by touch. Vidas: Yeah. And remember, you can do vibrato. Ausra: Bebung, so-called Bebung. Vidas: In German, Bebung, yeah--by gently pressing the key up and down, giving this constant pressure--up and down, up and down. And that’s what the vibration comes from. Ausra: Yes, and then playing on the clavichord, you understand what the meaning of the early fingering is. Because it’s impossible to play early music well on the clavichord while using modern fingering. Vidas: Exactly. So it’s very well suited for English music from the late Renaissance and early Baroque, especially because as we said, the key are very narrow, and the touch is very light, but you have to avoid thumb glissandos. Ausra: Yes, use position fingering. And by position fingering I mean you cannot use the thumb under… Vidas: Under--crossing the thumb under, you mean. Ausra: Yes, crossing the thumb under. Vidas: When you play a scale, for example, from C to C, then in modern fingering we do 1-2-3, 1-2-3-4. Ausra: And then 5-1-5. Vidas: So on the note F, we press with 1. And this thumb… Ausra: Goes under. Vidas: Under your palm. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: And crosses. Ausra: So you cannot do that while playing early music? Vidas: You have to keep positions. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: And shifting the entire palm into the new position. Ausra: That’s right. And also use a lot of the paired fingering. So if you have a passage with your RH, then the good fingers would be 3-4, 3-4, 3-4. Vidas: Yes. Ausra: If you are playing with your LH, the good fingering would be 2-3, 2-3, 2-3. Vidas: And it depends on the region and the country. Sometimes 1-2, 1-2, with Sweelinck, for example. But I wouldn’t worry too much about the differences between the countries--it’s too advanced detail. In general, use paired fingering for passages that remind you of scales. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: And keep position fingering for everything else. Ausra: And if you don’t have access to a clavichord, then practice on the harpsichord, or practice on a mechanical organ. Because if you only practice on an electrical organ or pneumatical organ, it will not do good for such music as early English music. Vidas: Well yes, it will sound unnatural for these modern instruments. And quite boring. Ausra: Yes, it will sound boring on the pneumatical or electric instrument. Vidas: Exactly. So then, another point is about ornamentation. Which fingers do you make ornaments with? Ausra: Well, if I’m playing a trill with my RH, I could do either 2-3 or 3-4. It doesn’t make much difference for me. Vidas: Mhm. Ausra: And actually, with my LH, I could do a trill with 3-2 or 3-1 sometimes even, maybe not so often 3-4 with the LH. Vidas: Mhm, mhm. Ausra: But I could do it. Vidas: For a long time I was amazed how you can do a trill with 3 and 4 with your RH, and I kind of avoided this myself; and only now I’m getting better with 3 and 4. My technique is getting better, I mean. Ausra: Good! I’m glad to hear it. Vidas: So, we’re all making progress, right? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: So guys, keep practicing slowly, especially on mechanical action instruments. Ausra: And you know, if you are struggling with ornaments, I would suggest you learn to play the pieces without ornaments first. Because what I have encountered while working with other people, or remembering the early age of my practice, is that if I tried to play ornaments right away, I would never play them well; and I could never keep a steady tempo in the piece. Vidas: Mhmmm. Ausra: So, you need to learn your music right rhythmically, without ornaments first. And when you are fluent with the music score, with all the musical text, then add ornaments. Vidas: Strange, I kind of forgot how I first learned music. And nowadays I’m learning with ornaments, of course--everything at once; but this is today, after 25 years of experience. So maybe other people need to simplify things at first. Ausra: Yes. And you know, if there are some ornaments that you are not able to play well, then just avoid them. Because nobody ruins a piece so well as playing ornaments in a bad manner, or you know, too slowly. Because they need to sound graceful. They are ornaments. And if some of them are just too difficult for you, then just don’t play them. That’s my suggestion. Vidas: Good. I agree. Please, guys, practice like we suggest; it really makes a difference in the long run. And keep sending us your questions; we love helping you grow. This was Vidas. Ausra: And Ausra. Vidas: And remember, when you practice… Ausra: Miracles happen. Ausra and I are preparing for a recital together which will be in 10 days were we will be performing solo and duet works by Sweelinck, Bach, Mozart and Mendelssohn.

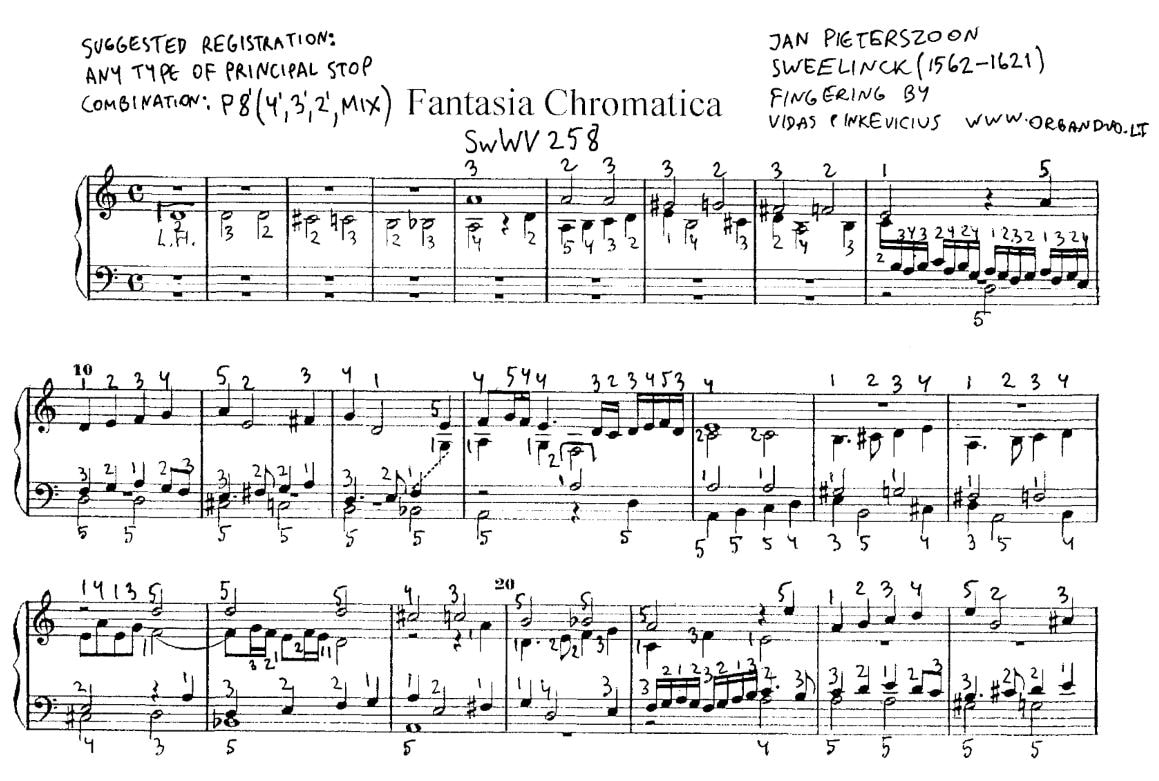

Ausra is playing the famous Fantasia Chromatica by Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck (1562-1621), "Orpheus of Amsterdam" and "the Maker of German Organists" as he was called back in the day to point out his artistic and pedagogical significance. The piece is called "Chromatic" because of the theme which is presented in the beginning. It is formed of descending chromatic tetrachord and later developed in all kinds of ways - canons, augmentation, diminution, double augmentation and double diminution. Interestingly, Sweelinck worked out not only the main subject but also the counter-subject so this piece is a pinnacle of polyphonic mastery before Bach. Of course it's so difficult to pick one Sweelinck's piece over the others because most of them are masterpieces. Fantasia Chromatica is so fantastic that I thought our students who love early music would want to play it too. Therefore I've prepared a PDF score with complete early fingering (5 pages) for efficient practice and instant articulated legato touch. It will save you many hours and give you the tools for historically informed performance practice. 50 % discount is valid until November 15. Enjoy and let us know how your practice of this piece goes. This score is free for Total Organist students. By Vidas Pinkevicius (get free updates of new posts here)

Today I recorded a video for David from Florida who asked my help in playing Handel's Largo. He is 71 years old and still trying to improve. Good for him! It's not too late. We never stop improving. Only when we stop living we can relax a bit. I noticed right away that he struggled with knowing what kind of fingers and pedals to use so I prepared a score for him with fingering and pedaling. Now he can progress much faster. Here are the rules I used if you want to do it for your own piece (created until 1800's): 1. For pedals, don't use heels. 2. For pedals primarily aim for alternate toes. 3. Do not cross your feet. Move them both together at the same time as one unit. 4. Same toes for long notes, extreme edges of the pedalboard and when the melody changes direction. 5. For hands, don't use finger substitution. 6. Use 2, 3, or 4 whenever possible. 7. Don't use finger glissandos. 8. The same fingers for the same intervals. Try this system when you're working on the early music piece. It helps you achieve singing articulate legato touch automatically, almost without thinking. If you need help with anything or feel stuck, let me know. |

DON'T MISS A THING! FREE UPDATES BY EMAIL.Thank you!You have successfully joined our subscriber list.  Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas

Authors

Drs. Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene Organists of Vilnius University , creators of Secrets of Organ Playing. Our Hauptwerk Setup:

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

This site participates in the Amazon, Thomann and other affiliate programs, the proceeds of which keep it free for anyone to read.

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed