|

VIDAS: Hi, guys. This is Vidas.

AUSRA: And Ausra. V: Lets start with Episode 146 of #Ask Vidas and Ausra Podcast. This question was sent by Paul, and he writes: I've been giving your question about practice much thought. I've been playing the prelude and postlude at my church now for several months and find I'm still getting nervous. I usually choose a hymn for the prelude and probably practice them 50+ times before I actually play because if my nerves get in my way, or I start to lose my place in the music, my hands will keep playing until I find myself. My schedule of playing was every other week, but I've asked to play two weeks in a row with one week off thinking that more time behind the console will be beneficial. A couple months ago I took a European vacation and was not in church for 3 weeks and dearly missed my practice. When I returned to play, I felt I took a step backwards because my hands were shaking as I played. Too much time away from the organ! You have taught me that slow practice is the key, but it's so hard to do sometimes because the inner battle says, "The faster you play, the more times you can practice this piece and you will learn if quicker". But it's just not true. You really do need to practice slowly to get the brain engaged to learn. I've been stuck on the Gigout Toccata for a few months. I can't quite get the whole piece to 1/2 speed (of 110 BBM) in practice. The slow practice in the beginning showed me I am able to play the first two pages at full tempo, and it happened quite naturally to my surprise. I've broken the piece in 4-measure increments and work on it almost every day. It's one of those pieces that will make me feel like a "real organist" when I finally play it in public. But then I'm sure another piece will come up on my radar. You and your wife's advice has been valuable and I'm so thankful I found you two. Thank you for what you do. Blessings, Paul V: Ausra, aren’t we grateful that people are finding that their use of our resources are actually growing in their practice? A: Yes! It is very nice to know that our advice helps someone to improve, and to know that we are able to help. V: Of course this process and progress is not an overnight success. A: I know. You must work on it. V: How long, Ausra, did it take you to become an overnight success? A: Overnight success? What do you mean by ‘overnight success’? V: This is the term. It takes about 7 years to be an overnight success. A: Well it took me more than 7 years to be a success. You know I have played piano since I was 5 years old. Now I’m 41 so count for yourself. And I still don’t feel that I am an overnight success. V: This term probably comes from the book publishing. Sometimes by surprise the stellar comes upright and the media picks up and celebrates the author: ‘Oh, it’s a surprise overnight success. We didn’t know about this author until yesterday. And now he is a millionaire, or she is a millionaire. And the order comes and tens of thousands of copies of the book are sold. Bestseller, right? But this is simply not true. That author probably banged on the keyboard for many years before anybody even noticed him. Right? A: Yes. V: Ten, sometimes even twenty years pass before someone published that book, and they never stopped, they never gave up. Ausra, do you have, sometimes, a wish to give up and stop practicing? A: Well, certainly, of course. V: Why? A: No, No! Sometimes even I get depressed like anybody else, but you know – life. V: What are you frustrated about in those moments? A: There are many things, sometimes, you know. Sometimes I just feel tired, you know, and have health issues, and sometimes I don’t have anything else, and I won’t give up practicing. Sometimes I think I am not living my life because I am spending too much time on the organ. Different thoughts, different reasons, as everyone does as well. V: Isn’t organ playing, for you, sometimes an escape from the troubles of the day? A: Yes, but not always. V: When the reality hits that you do have deadline to meet and you have to prepare a recital, it is not a hobby any longer, right? You ae a professional. A: I know. V: So I guess it is good for you to set a professional attitude for yourself. Then you feel all the motivation in the world to practice. You would feel responsible, and just like Paul writes, you could probably practice those hymns and preludes 50 plus times and it’s is not enough, probably. A: I know, and to know that when he writes ‘the faster you play, the more times you can play them’, that is an incorrect way actually. It is better to play them fewer times and to play them slowly and correctly. V: I have to be very honest here and to tell everybody that I have the same feeling that Paul does, all the time. I want to play everything at the speed of - light or sound - or perhaps at concert tempo, because it sounds better to me when I play it faster. The music is so natural when I play it faster. But, at the same time, in my mind I know that this is not the best way to practice because the slower you practice the more you notice the details, and the more you control the details, right Ausra? A: Right. And though I hear musicians practicing like this, they play fast and the music stops, and then they slow down their tempo, and it gets harder. And I know that quite famous musicians do that. But I don’t think that is such a good method. Because, after all, it might be difficult to keep a steady tempo during your final performance. V: I can remember now that in our student days in the practice rooms at the Academy, I heard people in the practice rooms banging the piano keyboard for hours. The same passage over and over again... A: ...and not making progress! V: And extremely fast. A: It is the complete opposite of what they should do-it is like banging their head against the wall. A: I know! I think the best way would be that it does not matter how many times you repeat a piece, or a certain hymn, or a certain passage for the piece. You must, each time, have some goal. It cannot be just repeating for repeating, repetition for repetition. That is not a good thing. I think you know the worst choir conductor is the one who makes his choir sing the same piece over and over again without setting goals. Then after a while, you are thinking, I have to do it again from the beginning, I must repeat it. But know that each time you must set some productive goal – it might be a little goal and on what you will focus when repeating this piece. This will make real progress fast. And give a purpose to your playing. V: It is called intentional practice. A: I know. V: It takes 10 years to do that. A: If you practice with an absent mind, it will be no work. V: Autopilot. A: Yes, because your fingers and feet must still be controlled by your brain. V: So guys, remember that it takes 10 thousand hours to of intentional practice to perfect any kind of skill. Take drawing, take painting, take writing – you know, a skilled writer, you have to write for 10 thousand hours. So if you can write 3 pages per hour – that’s reasonable, right? -- that is 30,000 pages of material you must write. So Paul, I think doesn’t need to despair with a lot of repetitions. You just have to be patient and enjoy the process, and not worry so much about the result. A: And I am so glad to know about his Gigout Toccata, that he feels like a real organist while playing it. And I think, you know, with the next piece it might get a little bit easier, unless that new piece is really much harder than this Toccata. But if he should pick up this piece that is similar and not a lot harder than the Toccata. Don’t you think so? V: Absolutely agree. And I think of micromanaging your progress every day or every hour and checking to see if you are better hour by hour. It is a little bit pointless, don’t you think, Ausra, because it is like planting a tree and then digging up your seedling every day to see if it has grown overnight. A: I know. It’s what Karlsson who lived on the roof did. He planted the peach and every day he would dig it up to see if it had grown and it had not because it did not have the opportunity. V: What you need to do guys is to forget about your progress for at least 6 months, and come back to the old piece that you have not been able to master 6 months ago, and then play it again and you can measure your true progress. A: I know. It is just like teaching my students harmony. At the 10th grade we started it, and at the 12th grade they finish it. They say in 10th grade it’s so hard. And you know if you would look at the 11th graders or 12th graders and to ask them about the harmony that we had in the 10th grade we just make some laugh: ‘oh, it was so easy’. Wait until you get to the 10th grade, then it will really be hard.’ That’s the same with organ practice. V: Even teenagers can understand it. So adults, especially motivated adults, have the mental capacity to understand the value of intentional practice, but without any rush, right? You have all the time in the world that you need. Some of us will live longer lives, some of us will live shorter. It doesn’t matter actually. What matters is that we sit down on the organ bench every single day. Just maybe for 15 minutes, or maybe a little more. A: But you know if you take a European vacation as Paul did, don’t feel guilty that you did not practice for that time. We need to have vacations, too. V: Yes, and when you come back from the vacation you can pick up from the start maybe from easier spot of course. Stop blaming yourself because you only live once. A: That’s true. V: Thank you guys. This is Vidas A: And Ausra. V: And remember: When you practice... A: Miracles happen!

Comments

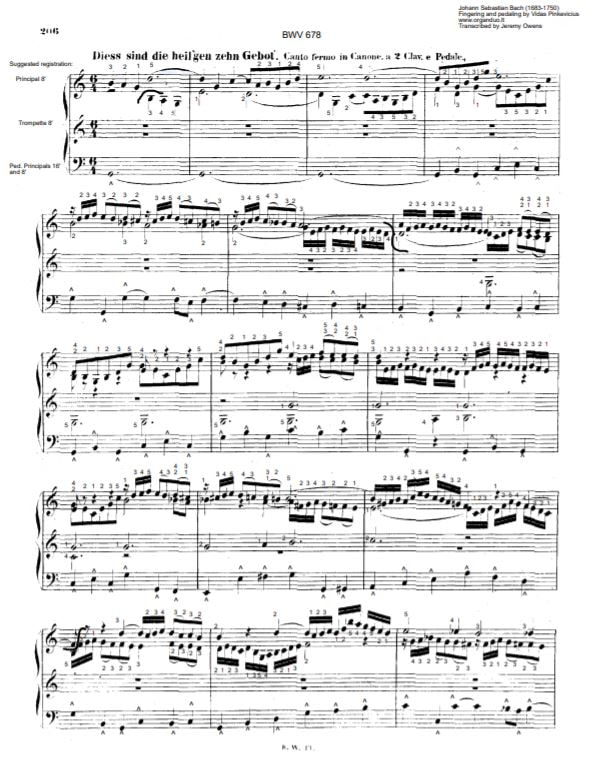

Would you like to learn J.S. Bach's Dies sind die Heilige Zehn Gebot, BWV 678 from the Clavierubung III? If so, my new PDF score with complete early fingering and pedaling will save you many hours and set you on the path of success to achieve the ideal articulate legato touch naturally, almost without thinking.

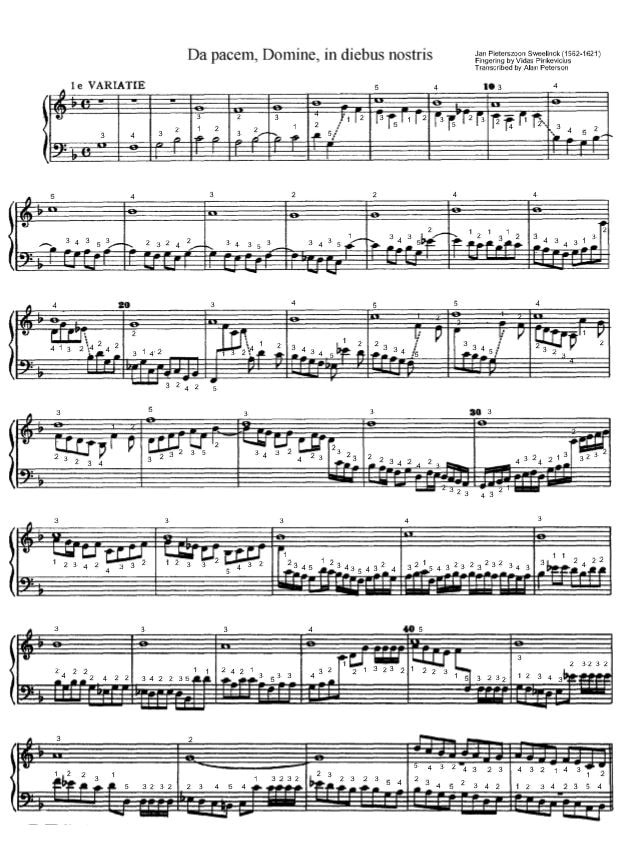

If you liked Kyrie, Gott Vater in Ewigkeit, BWV 669, Christe, aller Welt Trost, BWV 670 or Allein Gott, BWV 676, I'm sure you'll enjoy this piece too. Thanks to Jeremy for his meticulous transcription from my slow motion video! Check it out here 50% discount is valid until February 5. Intermediate level. 4 pages. This score is free for Total Organist students. Would you like to learn Da Pacem, Domine, in diebus nostris by the great Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck (1562-1621)?

If so, this score is for you because it will save you many hours of frustration. I have created early fingering for every single note which will allow you to achieve articulate legato automatically, almost without thinking. This set consists of 4 variations (manualiter only, no pedals): Variation 1: Bicinium with the chorale melody (cantus firmus) in the soprano Variation 2: Trio with the chorale melody in the tenor Variation 3: Quartet with the chorale melody in the alto Variation 4: Quartet with the chorale melody in the bass Note that these four settings are perfect example for anybody wants to creatively play hymn accompaniments. You too, can create duets, trios, and quartets from any hymn tune and place the melody in ANY voice. Thanks to Alan who meticulously transcribed the fingering from my videos. 50% discount is valid until February 5. Check out this score here Intermediate level. PDF score (4 pages). This score is free for Total Organist students. Welcome to Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast #131!

Today's guest Belgian organist Daniel Vanden Broecke. He received his basic music theory, piano and organ training with Erwin Van Bogaert at the municipal Music Academy in Berchem. At the age of 18, he continued his studies further at the Lemmens Institute in Leuven with Jozef Sluys, Reitze Smits and Joris Verdin. In June 1990 he obtained the diploma of "Organ Laureaat". Daniel won first prizes in solfège (1985), harmony (1988), counterpoint (1990) and organ (1990) in Fugue (1993). From 1990 until 2013 he was the organist at the Church of our Lady-birth in Hoboken. There he also accompanied the St. Caecilia choir and the soloists who performed various services. He was connected as teacher to the Academies in Berchem, Hoboken and Merksem (city of Antwerp) and at the “Antwerpse Volkshogeschool” as a course supervisor. From 2000 to 2004 Daniel was the coordinator to the “Vlaams Instituut voor Orgelkunst” that merged with the organ in early 2005 Flanders. After 4 years responsible for the communication with the members and promotion of cd’s members he is now Coordinator and he realizes pipe organ projects. Het Orgel in Vlaanderen ("The Organ in Flanders") is a non-profit association founded in 1990 in order to maintain and to improve the organ culture and the organ heritage in Flanders. This organ heritage should be re-valuated and brought to the attention of people who are not so involved like organists and musicians. The heritage contains a.o. organs who need to be restored or are already restored. A broader view contains the whole organ culture in Flanders, the instruments, the organists, as well professionals as amateurs, the organ students, and also the historical musical manuscripts and documents. Between 1990 and 2000 the most important issue was the realisation of "the Day of the Organ", organ concerts with free entrance (at first in Bruges, later on in different cities of Flanders), the making and distributing of photographs of Flemish historical organs, and the publication of a magazine for the members. In 2000 the Board of directors was joined by some deputies of the cultural world in Flanders, mostly people who were involved in the care of the monuments. The office moved from Bruges to Antwerp. The "Day of the Organ" became part of the yearly "Day of the Monuments", and was renamed "Organ on Open Monument Day". The website www.orgelinvlaanderen.be was started and contains also the monthly organ mail newspaper. The magazine for members changed from bimonthly to three-monthly and was named "Information magazine of Flemish Organ culture". The association grew and other activities were organised, such as the "Flemish Organ Days", when every two years a city was chosen where "The Organ in Flanders" organizes a weekend with a competition for non-professional organists, and with different concerts and workshops. There is also a Summer Academy. Since 2004 the association has an own cd-label "Vision-Air", with recordings that are called "Flemish Organ Treasures", in co-operation with radio Klara, the classical Flemish radio. Another part of the work of the association is advising and helping local projects that bring the organ heritage to a larger public, and co-operates in the exploitation of the organs in the Congres Center Elzenveld, by contacting organists and drawing up programs. In the context of the re-use of churches, finally, the Organ in Flanders support to church councils and others replacements of instruments and exploitation of organs. In 2015 a project to raise awareness children and young people for the organ was started: Orgelkids. A next step was the development of a digital app for children and young people. Pedagogical seminars for organ teachers are annually realized the in cooperation with OVSG. “The Organ in Flanders” is a partner of Herita and also works closely with the CRKC (Leuven) and Open Churches. In all of this the Flemish Government, department Heritage, is partner of "Het Orgel in Vlaanderen". In this conversation Daniel shares his insights about his work with Het Orgel in Vlaanderen and how these initiatives are reaching children of all ages. Listen to the conversation And don't forget to help spread the word about the SOP Podcast by sharing it with your organist friends. If you like it, feel free to subscribe to our channel on Musicoin. By the way, you can upload your own recordings to YOUR channel to maximize revenue. If you have some audio recordings of your organ performances, you can do the same. Feel free to use my invitation link to join Musicoin: https://musicoin.org/accept/MUSICa45e5f26ede2be5dd4411747 Thanks for caring. Relevant links: www.orgelinvlaanderen.be You can follow Het Orgel in Vlaanderen on Facebook and Twitter and reach Daniel on LinkedIn. AVA145: I Have Been Informed That If I Do A High Volume Voluntary It May Disturb People Talking1/27/2018 Vidas: Let’s start episode 145 of #AskVidasAndAusra Podcast. Listen to the audio version here. How are you Ausra today?

Ausra: I’m fine. V: And what are you planning to do in your organ playing today? A: Heh, heh, well, I have a lot of work of snow for a while at the beginning, and then just to go to practice. V: Me too. A: Because we have such a heavy snow, in Lithuania right now. V: Yeah, I hope in other parts of the world it is a little better. A: Well, not necessarily. I heard in the United States we have an extremely cold winter this year. And in Australia where is extremely hot. V: Hmm. A: I guess we are lucky. V: Yes. So today’s question was sent by Michael and he writes: “Good morning Vidas. Thank you for your email and Organ tips. I do not know if it too late to reply to your email. To answer your two questions I will first of all explain my situation. I am Organist at St Lawrence’s Feltham Roman Catholic Church and I play at 3 Masses at the Weekend for which I receive a small stipend. I also play for Weddings and Funerals and Kingston and Hanworth Crematoriums to make ends meet. I am also playing for a Funeral Director’s Carol Service this year. My dream is to get better and better and maybe perform at a Recital. I am a keen pianist and I believe I have nearly mastered Chopin’s Etude No. 1 Op. 10, but also like J.S. Bach of course and other composers. Unfortunately what holds me back from my dream is that I can only manage to practise on the Organ for about an hour a week in Church, and not loud pieces because the Presbytery is joined to the Church and people are working there. So I content myself trying to master the Trio sonatas and gentle pieces. I do try and practise sometimes The Finale from Vierne’s Symphony No. 1 at reduced volume and adapt other pieces that way for a closing voluntary as I have been informed that if I do a high volume voluntary it may disturb people talking. I have access to a Piano that my Mother and I bought. Also I have a bipolar disorder but this is controlled very well by medication, but I need to concentrate especially well when playing for services otherwise I could make a mistake, and I try and control my nerves. Thank you again for your emails and tips. All the best and God bless! Michael.” V: First of all, Ausra, isn’t it annoying when people tell you that you playing too loud, you’re playing too soft, too fast, too slow? A: Yes, but that’s what organists expect, in the this life now. I remember once I went to church to practice and you know, and the lady who got to the church, she just talked ‘oh, could you just come back tomorrow, I have such a headache’. Of course, I didn’t practice that day, but it was annoying for me because it took me almost an hour to get to the church. So that’s perfectly normal and I can understand very well this problem. V: Exactly. So, for me too, sometimes I go to church and there would be like groups of tourists coming in and the guide would talk quite loudly for this group and whenever I play the organ in the church I might disturb the guide there basically talking, so some of them like organ music, but some don’t so I had to occurrences when from downstairs the guides would even shout for an organist to stop playing at all. It’s really annoying. A: It’s annoying yes. Plus in our church, you never know when the funeral will be and it might, you know, spoil all our plans of practicing and it’s especially annoying if your recital is coming up and you really need to practice in the church. V: But we both know a regular organ is there and we can still adapt right? What if a guest organist comes from out of town even, from abroad? A: I know it’s very hard for him or her not to explain the situation. Yeah know, it makes you really feel guilty and very uncomfortable. Although you know you are not the reason why he or she cannot practice. V: So, for Michael, he is right I think, in playing sometimes with soft volume, don’t you think? A: Sure, it’s better to be in a good relationship with people in your church. But you know, as he told us that he doesn’t have enough time to practice on the organ, maybe he could find also another church which would allow him to practice and he could do it more often. V: Mmm, hmm. A: In exchange, let’s see, some service, some playing. V: Yeah, that would be quite possible, I think. You know lot places, there is a need or shortage of organists, so without even over extending yourself, you just offer occasional service, or if you don’t want to play in public you can make a small donation. A: I know. And Michael, wrote in his letter that he plays for a Roman Catholic Church. Maybe he doesn’t feel comfortable going to another new church denominational to ask if they would let him to practice. But I think he should be perfect lucky. V: Mmmh, hmm. A: Because, you know, for us organists, it’s just impossible to be connected to only one church. V: Exactly. A: So I think it’s perfectly fine to play in another church. At least in my opinion. V: And protestant denominations are more open actually A: Sure. V: For organist and musicians from all faiths. A: Because, you know, I miss that time that religion gives in the United States because there are so many open places just to go and to practice for us just being an organ student. Like in Michigan, in Ann Arbor, and Lincoln Nebraska you could go basically to almost any church to practice. And Methodist church were especially open for organists. V: Exactly. They have no problem with your faith. They don’t actually ask what your belief system is. A: Yes. V: At all. Unlike some of the Roman Catholic Churches. A: I know. V: Mmm, hmm. A: So, that might give him more opportunities, more time to practice on the organ. V: Excellent. A: But you know what I notice from his letter is that he is practicing trio sonatas and he can play them well. That is an excellent thing because I believe only experienced organists can master trio sonatas. So basically if you can play trio sonatas you probably can play almost anything. V: And he is playing Finale from Symphony #1 by Vierne. Yeah, so his level should be quite advanced, I would say. It’s very nice to be able to play those pieces. But should he stop here, and think that his skill is literally complete, perfected and set for life, or should he still try to improve? A: I think he, you know, each of us still has to improve something. None of us is perfect. V: And never will be. A: That’s for sure. V: Excellent. A: And you know he was talking about making mistakes sometimes, hard for him to focus during his performance. I think it’s not related actually to his illness, as he told us. But that each of us actually, has the same problem. I haven’t heard a person who would say ‘oh, it’s so easy for me to stay concentrated. I never make mistakes. Usually it’s otherwise. What do you think about that, Vidas? V: In this day and age, and in our society, there are more and more people who are in need of focusing because there are constant distractions everywhere, and it’s even harder to focus because we are bombarded by constant change of information, and it’s quite frustrating if you are playing the organ but your mind is all over the place, right? A: I know, but sometimes it’s hard to really concentrate, especially if you get some constant distractions. For example, during service, like, a baby starts to cry, or somebody starts to talk to loud during your prelude or postludes. V: Or a member from your choir comes up and starts to look at you or your music. A: Yes, that’s the thing, especially when you travel through Lithuania, you know, in order to perform, you have performance right after the mass, and the choir member of that local church who will sit in balcony, and will look at you like you would be, I don’t know, a monkey in a zoo or something like this. So sometimes people act really weird, don’t you think? V: Maybe they haven’t, you know, had an opportunity to look at such a high level organist from up close. A: But still we would need to think how you feel at that moment. You are a guest and you are performing and know. V: They think like it’s in a circus, right, you are a like a clown, not like a clown maybe, but like an athlete, like a circus athlete, or a circus artist and you are performing miracles in front of them, right, so they are in awe, basically. A: I know, but it’s still not good to look at you closely when you are playing or not to come and start turning pages of your score. Just to look around. I had an experience like that once. Or not to talk loudly among themselves, next to the organ bench. So that might be quite distracting. V: Could be. Could be. So, I hope this has been useful, this information, for our students, right? A: Yes. V: And now we’re going to go and practice some more, right? A: Sure. V: And take care of the snow, once it stops snowing. Of course it doesn’t make sense to shovel the snow while it’s snowing. A: I know, we cannot use our car. It will not move in the snow. V: And I will go to prepare the program notes for tonight's concert at our church, our guest organist is playing. And then later I’ll go to the concert itself. A: Excellent. V: Wonderful. Thank you guys, for sending these wonderful questions. Ausra and I are loving the process of helping you grow. And please send us more. We’re always here to help you out. V: And remember, when you practice, A: Miracles happen. V: Let's start episode 144 of #AskVidasAndAusra Podcast. Listen to the audio version here. How are you Ausra?

A: I’m fine thank you. V: This question was sent by Barbara, and she writes: “Hi Vidas, I appreciate these copies of sheet music with fingering. I would like to see the fingering for traditional hymns.“ This question is timely, right? We have just finished creating our 10 Day Hymn Playing Challenge. A: Yes. V: Can you tell us a little more about this challenge? A: We selected 10 hymns, 5 older ones, and 5 more contemporary ones. So basically those 5 traditional, or older, hymns require that you use your earlier technique, so no heel on the double-bars, no finger substitutions in your hands, and then those modern ones you have to do otherwise. V: Play with heel? A: Yes, and no playing legato in the manual part. So if you will be able to master all of these 10 hymns, I think this will be a key for you to your hymn playing in general. V: Yes. Wonderful. I am just looking at the feedback we have for the about these challenges, and it looks as though people are finding this useful, this resource, right? A: Yes. V: And to start to use them, and actually one person even asked us to make a copy of those hymns, but to produce the fingering for manuals only, of the exact 10 hymns. So this means they are using this entire resource, and it is helpful. A: I know. And maybe some are not using pedals so they need to know only to play the manual part. V: Yes. Since we do not have everything yet finished, right, in case you don’t have a pedalboard on your organ, what could you do if you have such a score? Could you write down left hand fingering? Could I adjust just a little bit? A: Sure. That is just your baseline. V: Yes. It would be a little more difficult, of course, but you could use a different color, maybe, if our fingering is not entered in black. So you could use green or red, or blue.... A: Yes. V: Right, or something of a bright color to see. And that person actually said that it is hard to adjust and notate on that particular score so he wanted to do the work, you know, that we would do the work for him, basically to take the same hymn and reproduce it for manuals only. But the problem is that we use the hymnal for this and the fingering is already notated on the original sheet of the hymns. So basically the pedaling and pedal indications are already there, we cannot erase them. But it is not a problem I think, right Ausra? A: Yes. You could use Sibelius software. V: And if you don’t have Sibelius, you can simply use a different pencil or different color notation. Or even enlarge your copy – make it very large – then the spaces between the notes will be larger and you will be able to see your fingers better. Your adjusted new fingerings, right? A: Yes, that’s right. V: But in the future, of course, we could create something, a format for manuals only. With other sets of hymns. A: That’s true, although if your accompany hymns at church for congregation I think it’s good to have a pedal part. It gives such a support for congregational singing. And playing hymns without pedal doesn’t suit me. V: That’s probably true in most cases. But what about an instance when you don’t have a pedalboard – maybe you have a piano? A: Yes. then yes. V: Then you need to work on that. A: But the thing is that when you are playing on the piano you don’t have the problems you would have while playing organ. V: Such as? A: Because for example, you can’t use the early technique when you are playing on the piano because it does not apply to piano as to an instrument. To use an early technique to do all that articulation. Or for example when you are playing modern hymns, then you know you have to use sostenuto pedal which will help you play legato. So basically, all that fingering and pedaling stuff is more important when you are playing organ. Because on the piano there more ways to cheat. V: The organ, and not even the keyboard, right? A: Yes, yes. V: So could we say, Ausra, safely and honestly, that it was the reason that I chose to do this for pedals also. A: Yes. V: Because it sounds better on the organ with pedals, these hymns. A: Definitely, yes. V: And probably people should not stop there, because to play soprano and alto with the right hand, and tenor with the left hand and bass with the pedals is just the basic setting, right? You could do all kinds of other textures if you are more adventure oriented and like to take a little bit of risk, right? A: Yes. V: Do you know what I mean, Ausra? A: Not exactly. Perhaps you could explain what you mean. V: Well, there are perhaps ten or more ways of playing hymns: in two parts, in three parts, right? And so you could omit the two middle parts and play the soprano and bass parts only with your hands. That is easy. But you could also invert the two parts, and make the melody in the bass, and supply the extra top voice with your right hand. That is a creative way of playing hands, right Ausra? A: Yes, that is right. V: And you could also play trios and place the melody in any of the voices, soprano, tenor or the bass. A: That is a very sophisticated way of playing hymns. V: Its fun, isn’t it? A: It IS fun but it is not for beginners or intermediates. V: Exactly. So perhaps that could be the next level. A: Yes. V: And when you have mastered a trio texture you could add a quartet, right, and you play your melody in any voice, soprano, alto, tenor and bass. Even with the pedals you could use not 8' level pitches in the pedal, but perhaps 4' level, or even 2' stops like Cornet in your pedal to play the soprano or alto. A: That’s right. There are all kinds of possibilities. V: And it was historically done in 17th century, and in 18th century people have been playing that and organ composers have created such hymn preludes like that. A: That’s true, but again, though I would like to return to that pedaling part, if you would think about North Germany which is home for Protestantism, or Martin Luther. And if you would look at the organ they had such huge pedal towers… And why? That was because we needed it for accompanying congregational singing. They needed a loud pedal part. V: And of course you played all kinds of choral fantasias and improvisations. A: Yes that is true, and the hymn tunes. V: Yes. So all those choral melodies are beautiful tools to demonstrate he colors of the instrument. And sometimes, if you do not have sophisticated pedal boards, and sophisticated pedal stops, you could have couplers from the manuals. A: Yes. That is why couplers were added to the organ. V: OK guys. Please use our 10 Day Hymn Playing Challenge. This really helps people who are starting to practice it – and let us know how it goes. It is interesting. A: Yes it is very interesting to know about your progress. V: Exactly. And send us more of your questions, right Ausra? A: Yes. V: We love helping you grow. And remember: when you practice... A: Miracles happen! V: Let’s start episode 143 of #AskVidasAndAusra Podcast. Listen to the audio version here. This question was sent in by Dan. And basically he comments after my question to him. I asked him ‘what is he struggling with in organ playing currently?’ And he wrote:

"With the Walther piece I find concentrating on the manual parts when the pedal enters, to be a challenge particularly, as in this piece, he’s got the melody in the pedal. I’m taking it way way slower then this at the moment though. With the Bédard suite, were doing things a little out of order, its a four movement suite. So I covered the first movement, and am working on the third right now. The third movement has a lot of suspensions in it, and I’m finding figuring out when parts move in those suspensions to be quite a challenge, but I’m getting it. And with the Dubois piece, its just a case of getting it smooth and polishing it up. I’ve almost got it." V: So Ausra, his practicing I think Walter’s, choral prelude, one of the collections, and then French Suite by Bedard, and then Dubois toccata. And with Walter he finds it difficult to play the manual parts when the pedal enters correctly. A: Well yes, that is often the case in Baroque music and Baroque pieces. V: Because it’s mostly fugal writing, correct? A: Yes, the polyphonic texture gives trouble to coordinate between feet and hands. V: Imagine if it’s like a fugette or even fugal texture then, the alto enter first, then the tenor, then the soprano, and only then the bass. And the instance where the bass or the pedals enter, then it’s four part texture. A: Yes, specific texture and you got a lot of things to do, to think, to listen to. V: I think that people take the first tempo, practice tempo, according to the first line. A: Yes V: Yes? And in the first line you only have one voice, it’s very easy and they tend to play to fast. A: That’s true and to know in general, I would suggest that if you have pieces like this, start to learn them and practice right away those hardest parts. Don’t play from the beginning. Then you see that texture is to fix that learning those parts, in combinations first, to play pedal separately. Then together, then start to learn those easier parts. Because, otherwise, you can play piece nicely, but not those parts where the pedals come in. V: Hmm, hmmm. A: So in order to make to make things even in the piece, throughout the piece, you need to start working from the hardest parts, from the beginning. V: That’s very natural, right? Let’s say, let’s say if the pieces just one line, solo piece, we have some pieces like this, especially in contemporary music. I’m thinking about Messiaen and his movements from Les Corps Glorieux for a single Cornet stop. A: Yes, yes. V: Or a reed? A: Mmm, hmm. V: So, it’s still difficult to play but not as difficult as let’s say, two voices, right? A: Yes, So true. The more voices you get, the harder it gets. Unless it’s a homophonic texture, then it’s another thing. But I’m talking about polyphonic texture. V: So in the polyphonic texture, if it’s just one line, and for everyone it’s different, but let’s say you can play this one line piece, collectively slowly with a few mistakes, then you need to go back, correct them, and probably, probably play it a few more times, right Ausra? A: Yes V: So five or ten times for one voice short episode. What happens if you have two voices? You have to repeat not twenty times but thirty times. Because you have one line, the second line alone, and both lines together. Thirty times. And if you have three part texture, you have actually seven combinations. That’s why you have to play seventy times. A: Your number scares me. V: I know. A: Stop counting. V: And if you have four part texture (I’m not finished yet), if you have four part texture, guess how many combinations? A: Too many, too many for me to count. V: Fifteen combinations, and if you give each combination just ten run-throughs, then you have 150 uh, plays to do. A: Well, you don’t have this so mathematical, exact or precise. But, the more you get the more you have to practice. V: Ausra, does it sound about right, if you have four part polyphonic texture, chorale, prelude or fugue or fuguette, that you need to practice that many times in order to fully master it. A: Yes, especially if you are a beginner. V: Mmm, hmm. We’re talking about people who have beginner skills or early intermediate. A: Yes. And another place he wrote about suspensions, my suggestion would be to lean more on those because suspensions always mark a dissonance in music and you have to lean more on dissonance. Because, after that resolution, usually comes. So that might help him too while practicing this piece. V: Mmm, you’re right. Um, what to you mean by lean on dissonances? A: Well, (chuckles) I didn’t mean like physically lean on them, but listen to them, and, V: Make them longer. A: Make them longer, yes. V: A little. A: A little bit, yes. V: Uh, huh! A: Not too much of course. V: And play them legato A: Yes. V: Suspension and resolution has to be played legato. A: Yes. V: At least it has to sound legato. A: Yes. V: In a very reverberant room maybe you could articulate a little bit. But if it’s dry acoustics, it definitely needs to be played legato. Those two notes. A: Yes. V: And with the Dubois toccata, I think he is on the right track, right? A: Yes. Although don’t practice that piece too fast too often because it might get muddy after a while. V: So maybe then dotted rhythms and reverse dotted rhythms might help. Slowing down and playing, tum, ta-tum, ta-tum. A: Yes, and know every time when you practice, play in a slow tempo too, not just that tempo. V: Mmm, mmm. True. A: That will help to keep things clean. V: Okay. It’s just a matter of spending time. A: Sure. V: And he will get it, eventually. A: Yes. V: Thanks, guys. Please send us more questions. We love helping people, right Ausra? A: Yes. V: And remember, when you practice… A: Miracles happen! Vidas: Let’s start Episode 142 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. This question was sent by David. He writes:

“I really can't thank you enough for making all this available. It has been my dream to be a proficient church organist (my wife is a United Methodist Pastor) and perhaps to do some recitals and some composing. I practice on a real Møller organ but where I play once a month is an electronic Allen organ. Your materials have kept me moving forward. You've spoken about lineage through you too Bach. Here, also is my lineage through Dean: 1. David Koch (me) 2. H. Dean Wagner 3. Barbara MacGregor 4. Marie-Claire Alain 5. Marcel Dupré 6. Louis Vierne / Charles-Marie Widor 7. Jacques-Nicolas Lemmens 8. Adolf Friedrich Hesse 9. Christian Heinrich Rinck 10. Johann Christian Kettel 11. Johann Sebastian Bach For all you do, thank you and God Bless, David” It’s amazing, Ausra, that people can calculate their lineage through ages until Johann Sebastian Bach, right? Ausra: Yes, it’s amazing; and I think they should be thankful to George Ritchie, who introduced us to this sort of thinking about J. S. Bach, and feeling like a part of that big organ tradition that lasts for centuries! Vidas: Although, when we published that early post about our lineage through Bach...it’s basically an idea. It’s a nice idea; but of course, we have to remember that among those masters, especially in the 20th century--in French tradition and even in German tradition--there were people who would do different things than Bach did, right? Let’s say, Marcel Dupré: he believed Bach’s music should be performed in one way. Today we are not agreeing with him, right? Ausra: Well, but these sort of things, these are just details, in terms of the larger picture. Vidas: Mhm. Ausra: I think the most important thing is that they are all carrying that organ tradition. Vidas: Absolutely. And that, of course, helps us to see the big picture. Ausra: Yes, and that also creates a responsibility on each of us, to be better, to practice more, and to be the best we can. Vidas: And what comes next? For example, our students... Ausra: Yes, and to spread our message as far as we can. Vidas: Right. If, guys, you are considering yourself, let’s say, our students...it’s a little bit dangerous, because we don’t know everyone, right? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: It’s a long-distance relationship. But still, our teaching across the globe spreads wide and far. And people might say, “Oh, we’re studying with Vidas and Ausra!” That’s fine! That’s fine...until a certain point, right? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: If it’s ethical. And then, what comes next? You have to think about your own students, right? Students--like, to the twelfth generation or thirteenth generation, too! Because then, your own students will probably continue this tradition, if you present it well. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: If you transmit it the best way you can possibly transmit, of course. Ausra: Uh-huh. And thinking about this, you know, chain of generations starting from J. S. Bach--it’s very interesting, because I’ve never thought that I’m so close to it; but when you start to count, then you see that happened not so long ago. Vidas: Exactly. Ausra: That not so many people are in between you and Bach! Vidas: And going further into history than Bach, you could say Buxtehude, right? And then, through Buxtehude, you could say things like Tunder, and Reincken also goes back, probably, through his interactions in let’s say Lübeck, and Hamburg was related there, too, so Scheidermann and Sweelinck come into play, at least indirectly, right? And then what comes before Sweelinck is also interesting: like, people from Italy--theorists and composers: Zarlino, right? The famous theorist and composer. And before him, in the Renaissance period, it can really, literally go into probably the earliest instances of organ literature that we know today. Not only organ; probably choral, too. Ausra: Yes. Church music, probably. Vidas: Mhm. So, organ music is maybe like 7 centuries long. The earliest instance of surviving notation is from about 1350 or 60, or the middle of the 14th century, basically: the famous Robertsbridge Codex. And they have several dances which are called Estampies; and we can at least hypothetically connect emotionally with that collection, too right? Ausra: Yes...maybe too far back, for me! Vidas: We don’t know what happened in those centuries, right? But yes. Do you think we could trace our lineage back to, let’s say, people who played Estampies? Ausra: Heheh! I don’t know. I don’t know this; but actually, I just read an article that, let’s say, for example, in Lithuania--we could all trace our lineage back to our only one king, Mindaugas. Vidas: Really? Ausra: I mean, yes, well, if a person had kids, and grandkids, it means that through a few centuries, their genes spread all over that area. Vidas: Mhm. Ausra: So they might all have...or maybe not Mindaugas, because I don’t know if his kids survived; but like, our Grand Duke Vytautas, that’s for sure--that we are all grandchildren of him. Vidas: Mhm. Ausra: Of his lineage. Vidas: This year in Lithuania is very special, because in 2018 we are celebrating the 100th anniversary of restoration of Lithuanian independence. Ausra: Yes! That’s actually the hundredth year of modern Lithuania. Vidas: Mhm. Ausra: Modern, independent Lithuania. Vidas: Yes. Ausra: That happened after the First World War. Vidas: February 16th of 1918. Ausra: Yes. You know, because the end of the First World War helped many European countries to declare their independence. Vidas: Yeah. But then, later, the Nazis came, and then the Soviets... Ausra: And then the Soviets came. And then the Soviet occupation began that lasted for 50 years. Vidas: And only finally in 1990, March 11, we declared our Restoration of Independence again. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: We’ve been independent for almost 28 years now. Ausra: Yes. That’s a good question--for how long. Don’t you think, sometimes, about this question? Vidas: Well, let’s hope the peace will last, and that reason will prevail, and emotions and madness will pass. I think political, diplomatic solutions are always a better way than military solutions. Ausra: Yes, that’s true. Because even when now, when we can spread our knowledge and share our thoughts with everybody in the world...that wouldn’t be possible otherwise. History would take another turn. Vidas: Yeah, like if some dictator would close down the internet, right? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: And we would have to be enslaved again, and... Ausra: Or you know, to just, to leave our country. That’s what happened, you know, during the Second World War. Vidas: A lot of people emigrated. Ausra: Yes, yes, when they saw that the Soviets were coming. Vidas: Mhm. Sad history. But we’re hopeful for the future; and we’re thankful, guys, that you’re listening to this, that you’re continuing this tradition, that you’re helping this tradition of many many centuries--after Estampies, after the Robertsbridge Codex, after Zarlino and Sweelinck and Bach--to continue. And we’re hopeful for the future, that through our efforts, and your efforts, too, that it will continue for many centuries to come. Ausra: Let’s hope for it! Vidas: Alright! And let’s practice now. Enough talking! Ausra: Yes, yes! Vidas: Enough theoretical hopes! Ausra: Don’t forget to practice every day! Vidas: Good. Thanks, guys! This was Vidas. Ausra: And Ausra. Vidas: And remember, when you practice… Ausra: Miracles happen. Welcome to Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast #130!

Today's guest is an American organist Randall Krum. He was born in Albany, New York and grew up in the nearby village of Ephratah where he studied piano and organ with local teachers. During high school he began focused organ studies with area organist, Dr. Elmer A. Tidmarsh, a onetime student of Charles-Marie Widor and a longtime friend of Marcel Dupré. Following graduation from high school and in preparation to audition for admission into college organ study, he studied with Willard Irving Nevins at the Guilmant Organ School in New York City. Subsequently he was accepted at the Peabody Conservatory, Baltimore, MD, where he studied with Professors Clarence Snyder, Arthur Rhea and Arthur Howes completing both the Bachelor’s Degree and Master’s Degree in organ and liturgical music. Mr. Krum has been organist at a number of churches in the eastern United States, notably St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church, Baltimore, MD, Sacred Heart St. Francis de Sales Roman Catholic Church, Bennington, VT, and St. Peter’s Episcopal Church, Bennington, VT. Currently, Mr. Krum is organist-choirmaster of St. Peter’s Episcopal Church, Lake Mary, Florida. In 1987, Mr. Krum was an American delegate to the International Congress of Organists in Cambridge, England, where he participated in a variety of organ and choral workshops. In Summer, 1993, he studied in Paris with organist Jacques Taddei and participated in workshops with Henri Houbart, Philippe Lefebvre, and Mme. Marie-Louise Langlais. In Summer, 2005, he attended the Royal School of Church Music International Summer School at St. John University, York, England, where he took part in courses and workshops led by John Rutter, John Bell, Alistair Warwick and other RSCM faculty. Additionally, he participated with all International Summer School students in singing daily Mattins and Evensong at Yorkminster. Mr. Krum has presented recitals at the Episcopal Cathedral of All Saints, Albany, NY, the Episcopal Cathedral of St. Paul, Burlington, VT, and for the Centennial Celebration of St. Peter’s Episcopal Church, Bennington, VT in 2007. His organ-related activities include membership in the American Guild of Organists where he is webmaster for the Central Florida Chapter and a member of the Executive Committee. In this conversation Randall shares his insights about how to keep being alive and interested in music as one ages. Listen to the conversation And don't forget to help spread the word about the SOP Podcast by sharing it with your organist friends. If you like it, feel free to subscribe to our channel on Musicoin. By the way, you can upload your own recordings to YOUR channel to maximize revenue. If you have some audio recordings of your organ performances, you can do the same. Feel free to use my invitation link to join Musicoin: https://musicoin.org/accept/MUSICa45e5f26ede2be5dd4411747 Thanks for caring. Relevant link: https://www.facebook.com/randall.krum Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 141 of #AskVidasAndAusra Podcast. This question was sent by Peter. He writes: “I think the amount of time we waste on things which are of no benefit is frightening. I wonder why? What makes the difference between the things you want to do (like eating tasty food, lying in bed, drinking to excess, wasting time on the computer etc.) and the things which you ought to do (practicing the organ, eating healthy food, getting to bed early, getting up early!) etc? An interesting psychological question. I suspect that a great deal of the answer is forming the correct habits, from an early age. The more you put into life, the more you get out of it.” So Ausra, we all know this situation, right? A: Yes, that’s so human-like. V: We love to procrastinate, to do things that are not necessarily worthy but are pleasant. What’s the reason for this, do you know? A: Well, I think it’s just human nature in itself that we seek pleasure in immediate gratification. It’s probably takes more satisfaction to eat tasty food which is not healthy like french fries or hamburgers and sweets instead of eating vegetables 5 times a day. But I think it’s important to force yourself to do other things, like practicing organ or going to bed early or eating healthier, I think looking to that final result of things. V: Which is what? A: Or further results, like playing recital or everybody praising you or lowering your blood pressure and exercising. V: But you see, Ausra, the final result for all of us is what? Death. A: Well, yes, if you would love from that perspective but since most of organists are Christian or at least I think so, you don’t think that with your death things will be over. V: So that’s why you need to eat vegetables 5 times are day and that’s why you need to floss your teeth. A: No, you do it just to make your life longer. V: I see what you mean now. A: I know, you’re making fun out of me. V: Not only out of you. I do this too so I’m making fun out of myself too. You see, I agree with you, it’s so difficult. We as humans tend to seek pleasure and tend to avoid pain. Two things in life. And not only humans - every animal. Every single our ancestor does this instinctively, right? A: Yes, I think so. V: But the difference with humans is we have so-called free will which not everyone believes we have. A: Yes, some people believe in predestination. V: Yeah. A: And that the choices are made for us from probably above. V: If you look from the scientific point of view, you could also argue that the world is governed by the laws of nature and that we basically behave according to the laws of nature but then there’s this question about unpredictability. Sometimes atoms in our cells and smaller particles than atoms move in unpredictable ways, like in quantum physics. So that’s I think the key to understanding that we sometimes can change our destiny and can behave in a different way than it’s destined, if you even believe in destiny. So with that in mind, I think there is hope, right? We can dream a little, make hopes for the futures, big goals and make plans and take steps to achieve those goals, right? A: That’s true, yes. And I think we have to find some sort of satisfaction in what we are making in practicing the organ. That the process itself would give us some pleasure. V: Exactly. Some people even say that the result is not that important as the process, as the journey. The journey is the goal, basically. To achieve something in life is not that important as to live a good life, basically. A: I think maybe our society is very much result-oriented. Don’t you think so? Like everything - educational system starting from an early age, having all those exams and grades. V: That’s what they call meritocracy. The better you do at school, right? Children hope to get better grades and with good grades they can get into a famous college, right? A: Yes. V: With famous college of course is a myth nowadays. It doesn’t matter anymore. But still many people believe this. And with famous college you could get a good job, right? Which is also not the case anymore. A: Yes, and you can make big money and you can become happy. V: For life. A: But it’s not necessarily true or not 100% true. V: So what makes people happy, Ausra? What makes you happy? A: I think small things makes me the most happier. V: Like what? Eating chocolate? A: Well, not so much chocolate but reading a good book, going for a walk. V: 10000 steps… A: Well, you are making goals already. V: My phone messed up and doesn’t count the steps I’m taking so I’m very frustrated now. And basically I lost motivation to walk. Because I don’t know how many steps I take. I may have to lie in bed today. I feel like I’m being robbed. A: But still you have to walk even if your phone doesn’t count your steps. V: OK. A: So for me happiness in small things. V: Of course doing things that you love is very important and that’s where organ playing comes into play, right? For some people it’s a profession, like for us. It’s what we do. But it’s even better if it’s your hobby, if it’s something you love to do in your spare time, then you can wait for this moment, wait for this privilege in your day to sit down on the bench and practice, right, Ausra? A: Yes, that’s right. And in general music gives me the biggest joy. Not necessarily playing but also listening to good music, to a nice performance. V: And then sometimes this short-term pleasure fades away, right? Because you have basically long-term hope that if you sit down on the bench and perfect yourself just one percent today and the next day and the day after that, after 72 days this percentage will double and it will compound and after one year it will be like 3800 percent of improvement in whatever skill you are trying to improve. So in the case of organ playing it’s I think a big deal after one year, right? A: Yes. V: So Peter if he’s struggling with let’s say motivation sometimes to get on the organ bench, do you think that he could think about that basic 1 percent improvement a day and not break a chain. If he, for example, had a calendar on the wall and notated X for every day that he practiced organ. X for a week, X for a month, X for 6 months. And then the entire point is simply to not break a chain of X’s, right? A: Yes. V: And it gives us pleasure in things routinely. A: That’s true. V: Would that work? A: Yes, that might work. V: Would that work for you if you would be struggling? A: Yes. You know, I remember when I was back in school I would check mark each day after it ended and I would count how many days were left until vacation. V: Aah. A: It was a good motivation to keep going. V: So it was for the upcoming pleasure. A: Yes. V: Of course there is fear of upcoming pain. Maybe deadline is also a good motivation, like recital. A: Yes. V: If you schedule a public performance or just a simple church service or even playing a short prelude and postlude in your friend’s church a month or two months from now, then of course you will have to announce for your friends and family that you will be there in two months and they will come to listen to your prelude and postlude. Then you will have all the motivation in the world, right? A: Yes. V: OK, what would be your final advice for Peter and people like him? A: Well, I think that everybody has to find their own way, really. Because we can suggest things that don’t work for them but try to look for new ways how to make yourself doing right things and to motivate yourself. V: What if people skip practice for one day, two days, three days? Should they scold themselves? A: I don’t think scolding yourself is a good thing. It’s not good for you. V: It’s very Christian though. A: Yes, it’s very Catholic. I think sometimes all the Catholic churches are built on that guilt. I think most of Catholics grew up knowing that feeling of guilt. And I don’t think it’s good psychologically, it might crush you down. So don’t feel guilt about not practicing. Just try in the future to avoid those long days without practice. V: Like in the morning… This is a new day, right? A: Yes. V: You wake up in the morning and you say, “Today will be a different day.” A: Sure. V: Thanks guys. This was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: Send us more of your questions. We love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice… A: Miracles happen. |

DON'T MISS A THING! FREE UPDATES BY EMAIL.Thank you!You have successfully joined our subscriber list.  Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas

Authors

Drs. Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene Organists of Vilnius University , creators of Secrets of Organ Playing. Our Hauptwerk Setup:

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

This site participates in the Amazon, Thomann and other affiliate programs, the proceeds of which keep it free for anyone to read.

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed