SOPP612: “I don’t really understand the difference between open and closed position chords”9/5/2020

Vidas: Hello and welcome to Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast!

Ausra: This is a show dedicated to helping you become a better organist. V: We’re your hosts Vidas Pinkevicius... A: ...and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene. V: We have over 25 years of experience of playing the organ A: ...and we’ve been teaching thousands of organists online from 89 countries since 2011. V: So now let’s jump in and get started with the podcast for today. A: We hope you’ll enjoy it! V: Hi guys! This is Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 612 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Diana, and she writes: “I don’t really understand the difference between open and closed position chords.” V: The context for this question was that I think I talked about harmonization in one of my recent videos on YouTube when I was trying to harmonize some chorale tune in either 22 ways or 28 ways, either in two, three, four, five, or even six parts. Do you remember those videos, Ausra? A: Yes, I remember you doing them. I haven’t watched them very closely, so I don’t know what you have been talking about. V: So one of the versions is to play soprano in the right hand and the bass in the left hand. That’s a two part version. A: Oh, okay. V: And then the voices can switch, and then gradually we come to the three part version, soprano in the right hand, alto in the left hand, the bass in the pedals, or soprano in the pedals, alto in the left hand, and the base in the left hand again. It could be this way, various dispositions, but again, it’s possible to do this in four parts, and the first exercise is to harmonize in closed position; one voice would be in the left hand part in the bass, and three upper voices would be in the right hand. Does it make sense? A: Sure, of course! I’ve been teaching harmony for many many years, so it makes sense. V: What is easier for you? Open or closed position? A: Well, it doesn’t matter, actually. V: Anymore. A: Well, if I want, of course, to make things easier, then I think closed position is more comfortable. V: That’s because you only worry about one voice in the bass. A: Especially if you are playing organ. You could play that bass with the pedal, and play the other three voices with your right hand, and you can just rest your left hand, which is so nice. V: Turning the pages. A: Sure. But anyway, if, you know, such question rises that you don’t know what the open or closed position is, then what can I say. It looks like she doesn’t have any formal musical training, because even in the music theory courses, people find out what closed and open position is. And for my students in the harmony course, I teach this thing during the first lesson, because basically the closed position is when the intervals between alto and tenor and alto and soprano voices don’t exceed the 4th. V: Interval of the 4th. A: Yes, the interval of the 4th, of course. V: For example, from C to F. Right? A: Well, yes. V: Or from D to G. A: Yes. Well, if they exceed the 4th, it means it’s an open position, that the space between the bass and tenor might be really wide or might be really narrow. It doesn’t matter. It doesn’t make any difference for the closed or open position. So basically, I’ll give you and example of a closed position C Major Tonic chord. It’s C-E-G-C. So you have, let’s say, a third between bass and tenor (C-E), then you have a third between tenor and alto (E-G), yes, and you have a fourth between alto and soprano (G-C). Now I will make the same chord and make it an open position. So you would have, let’s say C-G (bass tenor), and then you would have E in the alto, so between G and E, you would have an interval of a sixth. Then E would go to C. E-C would go from alto and soprano, it’s the interval of the sixth. So it’s open position. V: So in other words, an open position is C-G-E- and C. A: Yes, but this is only one example of closed and open position, because if you would take any root position chord, you could have like six basic general positions. Three would be closed and three would be open. But if you would have the first inversion of a root position chord, then you would have even more options, because you could also have positioned this which is neither closed nor open. It would be like a mixture of both. V: Mixed position! A: Yes, mixed position! And basically, every six chord has 10 positions, how you can place it. So it’s an entire science. V: I mean… you mean that the distance between three upper parts in the six chord can be either a third and a fourth? A: Well, it can be unison, too! V: Unison, yeah. Or it could be a fifth and a unison, which is also a mixed position. So many many versions. But I think for now, Diana doesn’t have to worry about first inversion chords. The six chord root positions are quite enough trouble already. A: Well, it depends on what your goal is. I cannot comment on that. V: I know she has ordered a harmonization book by Sietze de Vries, which starts with those simple root position chords and teaches people to harmonize easily various melodies. And, this is the first step for people who want to improvise. So, of course, we need to talk about other things, which this book doesn’t cover, and we have harmonization of the bass in the “Harmony for Organists” course level 1, and obviously other courses connected with Hymn Playing, or Harmonization, or Improvisation as well, so you can check it out. But yes, harmony starts with the first thing, and you have to understand open and closed positions. A: That’s right. V: Thank you guys! This was Vidas, A: And Ausra! V: Please send us more of your questions; we love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice, A: Miracles happen. V: This podcast is supported by Total Organist - the most comprehensive organ training program online. A: It has hundreds of courses, coaching and practice materials for every area of organ playing, thousands of instructional videos and PDF's. You will NOT find more value anywhere else online... V: Total Organist helps you to master any piece, perfect your technique, develop your sight-reading skills, and improvise or compose your own music and much much more… A: Sign up and begin your training today at organduo.lt and click on Total Organist. And of course, you will get the 1st month free too. You can cancel anytime. V: If you like our organ music, you can also support us on Patreon and get free CD’s. A: Find out more at patreon.com/secretsoforganplaying

Comments

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start Episode 222, of #AskVidasAndAusra Podcast. This question was sent by Samuel. And he struggles with recognizing patterns in the form of chords, completely and independent, and sight reading harmonies, especially hymns. V: Ausra, I think most of his struggles are related to chords and harmony skills, right? A: Yes. V: It’s not an easy skill to develop though. A: True. True. V: It takes perseverance and time. A: That’s right. V: Where should he start? What’s the first step, would be? A: Ah, probably he has to take some music theory. V: Basic music theory training, like our basic chord workshop, where I teach the chords and inversions of three-note chords, and four-note chords, even the ninth chord which is a five-note chord. A: True. V: Afterwards, he will be ready to go into probably more advanced harmony. A: Yes. V: Playing with two hands, not one. A: That’s right. And first of all you just have to start to recognize chord patterns. When you look at the score, and only after a few years, you might recognize while playing. V: I remember John from Australia in our long-term correspondence wrote a few times that he, after studying those chords in theory, he started to notice them in practice, in his compositions that he’s playing. But little by little, maybe not even in compositions but especially in hymns. A: True. V: At first. He said “oh, it’s a dominant chord”. Or, “oh, it’s a modulation. That’s where we have F sharp”. You know, things like that. Little by little, the new world starts to open up for him. A: True, but it’s a slow process. And anybody who has to spend quite a bit of time with it know that. V: Of course, it’s different for everyone. For us it was systematic training and we spent twelve years studying at the national level, art school, right? Where each grade we had to, to study ear training, and then later music theory, and then later harmony. So, do your remember back in your childhood, Ausra, were you conscious of those harmonies in your pieces that you were playing? A: No. Not at all. Because we receive a professional training in all those music theory disciplines. I think that the main mistakes and the weakness of our school training was that we very rarely applied them here in practice. Somehow these two, performance and theory existed on their own. And only later on when I became an adult, I myself started to draw conclusions and to search for a right way, or better ways, combining theory and practice. V: The same for me. I think the first piece that I played on the organ that was one of the chorale preludes from Orgelbuchlein, and I think it was "Jesu, meine Freude", BWV 610, by Bach. I was worrying about putting hands and feet together but not about chords and how the piece is put together. A: Yes. But I think understanding that composition with structure and seeing the meaning and the notes is very important. V: Especially when we teach adults. They have more developed sense of motivation. A: Yes. And especially when you are playing like chorale based works, because we also have a text somewhere, beneath those musical notes. And that also changes a lot. V: Sometimes you can even ask why is this chord, colorful chord here, and discover because of the text. A: True. So it is important to know what you are playing and to understand chords. V: Mmm, hmm. It’s good that Samuel is interested in that. Somehow it’s not a universally loved thing, an analytical approach to music. A: And it’s just too bad, because it we would look at the middle-ages when the university system started, started going in, in Europe, actually music was a subject of science. And it was taught together with math. V: Exactly. There is even a quote, a very famous quote about musicians and, and probably people who can understand music which is called ‘Musicorum et cantor magna best distantia’. A: could you translate it for everybody to understand? V: I’m trying to look up, yeah. Between musicians and singers, it’s a great distance. Which reads in Latin (This is the quote by Guido D’Arezzo. And I found it in Christoph Wolff’s book “Johann Sebastian Bach: The Learned Musician”.): Musicorum et cantor magna est distantia Isti dicunt, illi sciunt que componit musica Nam qui facit quod non sapit diffinitur bestia. A: And let tell couple of words about Guido D’Arezzo. V: OK. A: He was actually very famous for creating the musical notation system. So this is really one of the most, most important names in the history of music. So you need to, to know who he is. V: Exactly. He created the system that we use today, the solfege. A: Yes. V: So let’s translate this passage by Guido which is cited in Christoph Wolff’s book about Bach, which everybody interested in Bach’s music should read. And it, it goes as follows: “Singers and musicians; they’re different as night and day. One makes music, one is wise and knows what music can comprise. But those who do what they know least, ought to be designated beast”. A: These are strong words. V: In Latin beast is bestia. A: Yes. V: So, the meaning of this passage is basically, the person who doesn’t understand what he is doing is like an animal. A: (Laughs). Wow! V: Right? A: Well, V: In those terms. A: That’s a strong words. I would not put them like that. V: But that’s what Guido in the Middle Ages wrote. A: I know. V: Right? It’s… A: Way back. V: It was like a satire, right? Humor a little bit. So, but it just means that how this ancient, centuries old battle, between musicians and singers, between scholars and, and performers, went all the time. A: True, and I think that’s a nice quotation that Christoph wrote, chose for his book that he edited about Bach, ‘The Learned Musician’. Because in that book all the articles, they just help you to discover or to rediscover Bach and to show behind his scores, what he really did and how fascinating his music was, full of all those symbols and entire different world. V: Yeah. So although Samuel’s interest in chords is, is not perhaps related to Guido’s quotation of course. Not at all. He’s just is interested in knowing and recognizing chord patterns, just intuitively. It says that it’s extremely important too, for everyone who’s listening to this, to understand the meaning of, of those chords and structures, how the piece is put together. Basically, this is the preliminary step before you start to create your own music. And let’s face it, not everyone is willing to create his or her own music, right Ausra? A: True. V: And one of the reasons, I guess, I suspect is, that it’s not because of talent or lack of talent. Not at all. It’s because lack of knowledge. Lack of knowledge how those master, master works were created in the past, which could serve as models for us today. We should not of course copy them today, note by note. But use ancient techniques in a new way; combine and mix them together and create some new and original this way. A: That’s right. V: So I think, even though, Samuel doesn’t probably even aware, isn’t aware of, of, of this further steps, but his motivation to learn chords will definitely lead him into a realm of creating music too. Either on paper or on the instrument as in improvisation. A: Yes. Isn’t it wonderful. V: Absolutely. Amazing world! Every day you can learn something new from the treasury of organ music. And we wish you that. And please send us more of your questions. We love helping you grow. This was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: And remember; when you practice… A: Miracles happen! We're excited to announce that on the 333rd birthday of J.S. Bach our 7th e-book has finally seen the light of day!

I Find It Hard To Think Of Chord Progressions This is a collection of transcripts from #AskVidasAndAusra Podcast (107 pages). Vol. 7. (PDF file). For students who want to have all our ideas in one place. Here’s what you’ll learn in this e-book: 1. I FIND IT HARD TO THINK OF CHORD PROGRESSIONS 2. I DON'T HAVE A HOME ORGAN 3. MY CHALLENGE IS WITH CONFIDENCE 4. HOW TO EXECUTE THE B MINOR ARPEGGIOS OF TONIC CHORD OVER TWO OCTAVES? 5. MY DREAM IS TO BE ABLE TO PLAY ANY HYMN FROM OUR HYMNAL 6. I’M NOT TAKING ENOUGH TIME EVERY DAY TO PRACTICE 7. I NEVER HAD A TEACHER OR LESSONS 8. I’VE RECENTLY CHANGED CAREERS FROM WORKING IN IT TO NOW A FREELANCE ORGANIST/PIANIST 9: IS IT OK TO NOT FOLLOW WITH BOTH LEGS IN ORGAN PEDAL ARPEGGIOS? 10. HOW CAN I UPLOAD ONE OF MY PIECES TO MUSICOIN? 11. I HATE MOST MODERN ORGAN MUSIC 12. WHEN IS IT TIME TO STOP PRACTICING YOUR ORGAN PIECE? 13. WHAT ARE SOME OF THE BEST AND WORST STOP COMBINATIONS? 14. THERE IS A GREAT AND PROFOUND JOY IN PRACTICING AND PERFORMING ON THE ORGAN 15. SHOULD YOU KEEP YOUR ORGAN PLAYING GIFT A SECRET? Until March 28 this e-book is available for the low 2.99 USD price. If you liked our other e-books from #AskVidasAndAusra collection, I'm sure you will enjoy this one too. Check it out here Free for Total Organist students Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start Episode 174 of Ask Vidas and Ausra podcast. This question was sent by Russell. He writes “How to make sense of the chords in the third movement of Messiaen's L’Ascension in order to learn them fairly fast.” Oh, this is a very famous movement, right Ausra? A: Yes, it is. V: And very interesting question. I played this piece a number of years ago and I it’s a fantastic movement. I think I’ve even recorded a video of this performance from St. Paul’s United Methodist Church in Nebraska, Lincoln. On the organ built by Gene Bedient. Remember that recital? A: Yes, I remember it. V: And I think one of comments I received from one of the YouTubers was that I shouldn’t teach people because I play with mistakes. That was really funny. Because, yes, in one of the passages I made a mistake or two in this particular movement. Usually I don't reply to such comments but this time I couldn't resist and asked if he has his own video of this piece from which I could learn. Of course he didn't reply... People who put themselves on the line normally don't criticize others because they know what does it take to be vulnerable. So, then the question is how to make sense of the chords?Obviously, Russell has to be familiar with the modal system that Messiaen is using, right? A: Yes. V: And the best place to get familiar with this is his treatise which is called “The Technique of My Musical Language” which in French is “Technique de mon langage musical.” Forgive my french pronunciation. So, basically in this book Messiaen writes out his influences, rhythmic influences, modal influences, even gregorian chant influences, bird calls influences, hindu rhythms and other things. Right, Ausra? Let’s suppose Russell has read a chapter or two from this book where he would find information about the modes. Right? What else? A: Well that’s the thing. I have you know, read quite a few books actually about Messiaen compositions, about his compositional techniques, which basically consists of you know imitating birds singing, the modes of limited transposition, added note values, and some hindu rhythms, some gregorian chants, you know, influences. But basically, I don’t think it helped me to learn his music faster. Maybe it helped me to understand his music better, but then working on the music itself, on his texts himself, I think I still have to struggle quite a lot. V: Me too. It’s not an easy technique. It’s not an easy writing style. Because he was so original at the time. But what helped me was really to study the modes one by one. And by studying I mean is playing a scale based on this mode from the note C with my right hand only in an octave, a range of one octave, then in two octaves, then in four octaves, then with the left hand up and down, then two hands up and down and treating this mode just like a regular C Major scale and getting familiar myself with it. And then transposing from the note C# and then from D, and then from any other note that it’s possible. Because their modes of limited transposition and you cannot transpose them endlessly. A: Yes, since you reach a certain point you cannot transpose them anymore, that’s why it’s titled modes of limited transposition. V: And then you could play scales of double thirds, or scale of double fourths, or even sixths in each hand just like regular warming up exercise you would find in Hanon or anywhere else. A: But what about particular L’Ascension cycle? What would you do with those chords? V: You take an opening, remember you have big chords at the beginning and then you have to decipher those chords which means you write down on the staff the scale based on those chords and you find out what the mode is. A: But technically would it help you to apply it to the keyboard? V: It would help me. A: And you play it with mistakes, yes? V: Yeah, I’m famous for playing with mistakes. But that doesn’t stop me from playing you see. And the person who makes the most mistakes wins always because they try the most. And Russell can try the most also if he tries to transpose those opening fragments or in the middle whenever he is struggling, wherever he finds difficult spot. A: Wouldn’t it mix him up even more, and would make things even harder? V: Yes and no because Messiaen himself transposes fragments of his modes in the same piece too, in several spots. A: So then why just not you know to exercise more to work on those spots, hard spots more? V: That helps. A: In various tempos, in a slow tempo first and then move tempo ahead a little bit and maybe you know to practice in different rhythmic formulas. V: Dotted rhythms. A: Yes. V: You are right it will help. But you see what you need to do if you are Russell, you need to understand how the fragment is put together, you have to basically deconstruct it. And by creating a mode, right, a string of notes, ascending string of notes based on those chords would help you to understand which mode of limited transposition Messiaen is using at the moment. And then you see “Oh, it’s a second mode”, “Oh, it’s a third mode”, “Oh, maybe it’s a fourth mode.”, you see and maybe even label them on the score with pencil. A: Yes, but it’s very much time consuming don’t you think? V: Oh, what’s the rush Ausra? A: I don’t know. V: We have all the time in the world I think, right? And we are not competing with anybody, right? We are not competing with Messiaen, he’s dead already. May he rest in peace. And we are only competing with ourselves, right? What we achieved yesterday, and today, and tomorrow maybe if we live. Anything else Ausra for parting advice for Russell and others who want to study Messiaen. A: Well be patient. That’s a hard music to learn. V: And if you have never played Messiaen before don’t start with L’Ascension. Right? A: Start with “Le Banquet Celeste.” That’s I think a good piece to start. V: Or maybe “Apparition de l’eglise eternelle” A: You know they both use extremely slow tempo but I think that’s a good way for beginning to learn Messiaen. V: But don’t play “Diptyque”, right? A: Yes, it’s just the second piece that Messiaen composed to the organ but it is very hard. V: Ausra has special memories about this piece. A: Yes, and you know I don’t like those memories. V: It’s more similar to Vierne style than to Messiaen. A: I had to learn it like in a week or two and play it in master class, that’s what’s an awful way to do. V: OK guys, we hope this was useful to you. Please apply our tips in your practice and send us more of your questions. We love helping you grow. This was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: And remember when you practice… A: Miracles happen. First, the news:

Final by Louis Vierne with fingering and pedaling from Symphony No. 1. 50 % discount is valid until December 6. Free for Total Organist students. PDF score (14 pages). Advanced Level. And now, let's go to the podcast for today. Vidas: Let’s start Episode 118 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. Listen to the audio version here. Today’s question was sent by Neil, and he writes that he finds it hard to think of chord progressions and keep on sticking to a few major and minor keys. Basically, Ausra, he needs to progress, but he’s stuck, right--with harmony. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: So...Do you have students like this in your classes? Ausra: Yes, of course I have them. Vidas: Who only love a few keys, like C Major, a minor, G Major, e minor, F Major, d minor--and that’s all! Ausra: Yes, that’s right. I have such students. Vidas: Do you sometimes ask your kids in which key your dictation will be today? Sometimes I do. Ausra: Yes, I do. Vidas: And what do they reply? Ausra: “C Major!” Vidas: C Major, right? What about E Major? Probably never. Ausra: Hmm...not too much. Vidas: Right? So, young people love keys with zero or one accidental. Ausra: That’s right. But we have to use all keys. Such is life. Vidas: You have some experience with key characters, right, now? Ausra: Yes, because I’m going to have a recital, actually. To… Vidas: Announce and to lead, right? Ausra: Yes, to lead the recital, yes. Which is called “ABCs;” and the idea of this recital is that I will have to talk about different keys and their meaning. Vidas: So what are the keys that will be in the program? Ausra: Well, basically, 12 pieces of a minor, 8 C Major, and then I think 2 or 3 A Major, 4 c♯ minor (wow) Vidas: Uh-huh. Ausra: 3 c minor, and only 1 b minor. Vidas: Uh-huh. Ausra: And no other like piece--no B♭, no minor or major, no. Vidas: So why do people...why are there so many keys, by the way? Why can’t a composer create everything in C Major or a minor? Ausra: Well, because you know, in old times, different keys sounded differently, and each had its own character. Vidas: That’s why they chose different keys, right? Ausra: Yes, yes; and only after 1917 all keys started to sound the same--you know, after all instruments started to be tempered in equal temperament. Vidas: Mhm. Which is now changing, of course, because of the movement in early style and early performance practice. Ausra: Yes, that’s right. That’s right. Plus, we are organists; we have so many historical instruments that are tuned in different temperaments. Vidas: Mhm. So you are going to explain all this, a little bit? Ausra: Yes, a little bit, because there will be kids from first grade till the end of high school, so my talk needs to be appropriate to everybody. So I cannot talk on a very high musicological level. Vidas: Not like we are talking today? Ausra: Oh, don’t make fun of me! Vidas: Hahaha! Excellent. So, what are the differences between some major keys--let’s say, what is the most joyful key, do you think? Ausra: C Major, probably. Vidas: C Major, right? Ausra: But F Major is joyful, too. And A Major. Vidas: E♭ Major might be a different character from C Major, although it’s a major key, too. Ausra: Yes. But for example, A♭ Major, you know, is the key of “grave”… Vidas: Grave key, right? Serious key. Ausra: Yes, it’s a serious key, although it’s a major key. Vidas: Strange. Ausra: So there are very interesting things, actually. Vidas: And with minor, too, there are some characteristics of sadness, melancholic keys; but there are also sorrowful keys, which is not the same; and also some pathetic keys, like very dramatic, like c minor… Ausra: Yes, that’s right, yes. Vidas: There is a reason why composers chose to have a “pathétique” sonata, right-- Sonata Pathétique (by Beethoven), in c minor. Ausra: Yes. And actually, its middle movement is in A♭ Major. Vidas: Uh-huh, uh-huh. True. And in different historical periods, composers chose different key relationships for middle movements. Do you remember, we have been playing Franz Seydelmann’s 4-hand sonatas? And middle movements are always in the key of the subdominant. Ausra: That’s very often the case with Classical sonatas, say with Mozart. Vidas: Mhm. Ausra: You very rarely find keys of dominant in the middle movement. Vidas: And even no keys with parallel major or minor. Ausra: Yes, yes Vidas: As was the case with Baroque music. Ausra: Yes, but then the Romantics already did things differently. For example, like Edvard Grieg, his famous Sonata in A Minor--the middle movement is in C Major. Vidas: True. So, Neil and others could really benefit from looking deeply into the keys and their meaning, right? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: And discovering, for example, the differences from one piece in one key and another piece in another key, of the same composer, let’s say, because it will be easier to compare. Ausra: As Neil said, he has a hard time understanding chord progressions. Vidas: Yeah… Ausra: Actually, you need to study chord progressions before actually playing or learning to play that piece, just for a better understanding of how music is written. But when you will actually perform it and learn it, you won’t always have to think about every single chord. Vidas: There is no time for this. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: You have to make music. Ausra: That’s right. Vidas: So, in order for him to understand chord progressions and get better acquainted with different keys, could he try playing sequences? Ausra: That’s right, yes. And YouTube is full of my sequences that I played as examples for my students. Vidas: True. And this helps, right? Ausra: Yes, it definitely helps. Vidas: Mhm. Because you can take a very simple chord, like a dominant 6 chord, and play up and down; so you can play those sequences in descending motion or ascending motion, right? That would help, right Ausra? Ausra: Yes, that would help; and it would help you to get familiar with all keys, and to feel comfortable while playing any key. Vidas: You can stick in one key: that is called the tonic sequence... Ausra: Yes, but you can, you know, transpose them to different keys. Vidas: ...While choosing a particular interval, like a major third, minor third, or major or minor second. That helps. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: Wonderful. Guys, please send us more of your questions; we love helping you grow. This was Vidas. Ausra: And Ausra. Vidas: And remember, when you practice… Ausra: Miracles happen.

First, the news:

Our 4th e-book "MY GOAL IS TO BE A BETTER CHURCH ORGANIST" (And Other Answers From #AskVidasAndAusra Podcast) is available here for a low introductory pricing of 2.99 USD until October 4. Please let us know what will be #1 thing from our advice you will apply in your organ practice this week. This training is free for Total Organist students. And now let's go on to answering people's questions for today. Vidas: Let’s start Episode 77 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. And today’s question was sent by Jerome, and he writes, “Can you please tell me the notes in this b minor chord progression?” And the chords are as follows: iv, ii 65, V42, i6, and V43. So, Ausra, I think this is a rather simple question about expanding and explaining chords to people how they actually need to be understood, right? Ausra: But first of all, he just asked us to tell the notes, what the notes would be-- Vidas: In b minor. Ausra: In b minor. So the first chord would be E-G-B... Vidas: E-G-B... Ausra: Then the second chord would be E, G, B, and C♯... Vidas: That’s a second scale degree 65 chord. Ausra: Yes. Then the next chord would be E-F♯-A♯-C♯. Vidas: That’s a dominant 42 chord. Ausra: Then next would be D-F♯-B-B. Vidas: That’s a tonic 6th chord. Ausra: And the next would be C-sharp-E-F♯-A-sharp. Vidas: The last one, dominant 43 chord. That’s all in b minor. By the way, you can play everything in any key you want, in any minor key you want--it’s a nice transposition exercise. It expands your theoretical knowledge to other keys as well. Ausra: I would say that’s a little bit of strange progression, because it doesn’t end in a tonic key, and begins not in a tonic key. Vidas: So what could be the last chord, in your opinion? Ausra: The last would be a tonic. It would be B, D, F♯, and B. Vidas: B, D, F♯, and B. Ausra: Also it’s a strange way to begin a progression on a subdominant chord. Vidas: So before the subdominant, before this minor iv, you might probably need to use tonic. Ausra: Tonic, but maybe 6th chord would be best, so it would be D, F♯, and B at the beginning. Vidas: Can we spell them out in 4-part notation, just like in your harmony exercises? Ausra: Definitely, yes. Vidas: Because now we’re using the simple 3-note notation to be able to play with one hand only. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: If you want to play with both hands, you have to use 4 parts, SATB, and sometimes closed positions, sometimes open positions. So the first would be, let’s say, tonic, right? And tonic would be, in b minor… Ausra: Well, if you want to do the subdominant next, then it would be easier, for example, for the beginners to not start on the tonic but to start on tonic 6th chord. Vidas: Okay, so D in the bass? Ausra: That would be a smoother progression. Vidas: D-B-F♯-B. Starting from the bass… Ausra: But in order to play chords like this, you have to have basic knowledge of harmonizing things. I don’t think it will be much use to our audience, if you will say this progression again in an open position. They just have to start with harmony--learning harmony from the beginning. Vidas: So it’s too hard, right? Ausra: I think so. Vidas: Ok. Ausra: That’s an entire course. Vidas: Okay, so guys, if you want to play those 3-note, 4-note chords, in 4-part notation using both hands, and even learn to harmonize hymns, you need to learn the basics of chord progressions, and basic harmonic rules--how the voices have to move between the chords, and what is forbidden, for example. Ausra: Because you know, resolving only one progression will not teach you harmony. If you cannot read chords like this, as I understood from his question, that means you have no basics of theory and of harmony. Vidas: Okay, so we can recommend something. We can recommend a few courses. Probably the beginning course would be Harmony for Organists, Level 1. And I explain in this course all the major and minor, root position and first inversion and other inversions, tonic, subdominant, dominant chords, and even dominant 7th chords and inversions; and I will teach you how to harmonize the melody in the soprano. And that will get you started...and moving to the world of harmony, which is very useful if you are interested in playing hymns and understanding organ music that you play, for example. Okay, guys. Hope this was useful to you. Please send us more of your questions. And remember, when you practice… Ausra: Miracles happen. #AskVidasAndAusra 40 - Identification of sounds to the appropriate chords is a problem for me8/1/2017

Vidas: Let's start Episode 40 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. And today's question was sent by Parvoe who writes, “identification of sounds to the appropriate chords is a problem for me”. Could you explain how do you understand this question Ausra?

Ausra: Well actually I think if I understand it right, that when he learning maybe a new music. It’s hard for him to tell by listening to those chords, if the notes are appropriate or not. So he is playing basically a correct chord, I think that's the problem. Vidas: So that's the hearing problem right? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: So imagine you are playing a piece, let's say by Bach Chorale Prelude, and in other words he cannot understand what does this sound, this note mean. Which chord would go with this sound, with this note? Does this make sense? Ausra: Well yes and no. The trouble might be, I see a double problem in this type of question. One thing might be that he does not know the keyboard harmony well enough and another thing that his harmonic pitch might not be developed enough yet. Because sometimes people can have a perfect pitch, and very good melodic hearing, but they cannot have like no harmonic pitch. That's different. Two type of different hearing of music. Vidas: Do you think that one is born with this pitch, harmonic pitch, or one can develop this over time? Ausra: Well, some people, of course we are born with that kind of pitch, but I think you can develop it and for people who play melodic instruments, like violin, flute, oboe and so on, usually they develop better melodic pitch. But people who play piano, organ, harpsichord, even choir conductors they develop harmonic pitch too. Vidas: Even guitar. Ausra: Even guitar, then you have sort of chordal structure, you can develop well the harmonic pitch. Vidas: So basically what you are saying, organ playing really helps to develop harmonic pitch. Ausra: Yes. But of course if that's trouble for you, if you cannot hear, if that note belongs to that particular chord, that means that you have to analyze music that you're playing. So just to study the harmonic progression. Play those chords separately. Maybe write the names down and that should help, I think. Vidas: Well exactly. What kind of chords are the most crucial in any tonal composition? What kind of type of chords? Ausra: Tonic, subdominant and dominant. Vidas: Three chords? Ausra: Yes and of course three versions and then all kind of other modifications of these chords. Vidas: Here is the thing guys; if you know the key of the piece that you are currently playing, and you know the circle of fifths, and you know those three types of chords as Ausra was mentioning earlier, tonic, subdominant and dominant, you can basically identify the meaning of any given chord. Not necessarily it will be very precise, you will not necessarily be able to identify diminished seventh chord and it's inversion or let's say six scale degree first inversion chord, but when you know tonic, subdominant and dominant, and you compare those three chords to any given chord that you are playing in your music, you will see that some notes will match. Am I right Ausra? Ausra: Sure. Definitely. Vidas: And then you can say, oh this is a tonic function, or this is dominant function, or this is the subdominant function. That's enough for starters don't you think? Ausra: Yes, that's definitely enough. And just be careful when you are learning a new piece of music because it’s very easy to learn it in incorrect way, the wrong notes, and then it will be very hard for you to correct it. So just be very careful at the beginning. Vidas: It's always very good to basically lead with your mind and not with your finger. Ausra: Sure. And in any given piece of music usually you start on one key and then the key switches, it can switch for a short time, but it can modulate for a longer time and then go back and travel through keys, so just know that tonal structure of your piece this will help you too. And write it down in the score, it will help you to learn the text correctly. Vidas: And to understand the meaning of the notes. Ausra: Sure. Vidas: And basically we will be thinking like this composer who created this masterpiece. Ausra: Yes, and after a while you will see some sort of tendencies like cadences, you will start to identify them and know infrastructure also help you to play music in the right manner, not to play like robot, but to play more musically. Vidas: Do we have any trainings that we could recommend for people to improve their harmony and analytical skills, Ausra? Ausra: Yes. We have some of them. Vidas: The one for example, Harmony for Organists, if you want to start from the beginning, Level 1. Or, Hymn Harmonization Workshop I think that would be helpful too. Or even Bach Chorale Analysis Workshop where you will learn to analyze four-part harmony found in Bach's chorales. Ausra: Yes, or you know you can on youtube just find my videos, with harmonic exercises which will be I think very helpful for you to try to play yourself some sequences or modulations. Vidas: Yes. Ausra: Or basic cadences. Vidas: Excellent. So guys please apply our tips in your practice and let us know for example, what was number one thing which was the most helpful thing to you this week and you applied it in your practical playing this week. This is really helpful. We would appreciate it and this of course will help us produce even more helpful podcasts for you. And please send us more questions that you might have, more challenges. We love helping you grow. The best way to do this is through subscription to our blog when you go to www.organduo.lt you enter your email address and you become a subscriber and you will receive this free ten-day organ playing mini course with our lessons on how to master any organ composition. This is very helpful in the long run. And then you can reply to our messages... ...Oh, you can hear our dog barking in the background. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: Somebody is coming. So, we better run to check. Okay. This was Vidas. Ausra: And Ausra. Vidas: Have fun practicing.

Swallows breakfasting

Above my head while I write Chords above the staves.

Today's question was sent by Robert. Here's what he writes:

I'm practicing the last section of BWV 572 and wondering if at that fast tempo it's best to just write down the chords above the staves. What do you and Ausra think about that? Thanks again! Listen to our full answer at #AskVidasAndAusra Please send us your questions. We love helping you grow. TRANSCRIPT: Vidas: Today is the 32nd part of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. Please send us more questions. Today's question was send us by Robert. He is practicing Piece d'Orgue BWV 572 by Bach. He writes, "I wonder if in that fast 32nd note tempo it’s best to just write down the chords above the staves. What do you and Ausra think about that? Thanks again." So, Ausra, I think he struggles with the ending part, right? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: Très vitement, Gravement, and Lentement. The last one, Lentement. The last part where you have 32nd note passages. And he suggests, maybe would it be helpful to write down the chords above the staves in order to grasp the meaning of the chords and master this passage easier. Ausra: Yes. That's a good idea, if you know what those chords mean. It depends on how advanced you are in keyboard harmony, because for some people to realize what the written chord is might take longer than actually to read actual music. So, it all depends on that. But you know, if you are advanced with harmony, then yes, go ahead and write the chords down. It might be very helpful. Vidas: But you have to know the meaning. I remember also, when practicing this piece a number of years ago, you see you have to understand how the chords move in this passage, right? So, not every note in this passage is a chord or a note. Ausra: Sure. Vidas: I think five notes in the hands, total, and one is in the pedal. So you have to skip, in your mind, every other note, I think. Right? And they then constantly change note by note every half of the measure. Ausra: Yes. I think, you know, the best way would be probably just to memorize those couple of pages in the last section. This would be the very easiest way to do it. Because, I think when you will be playing in performing tempo, final performance tempo, you will not have time, neither to look at the score, nor to look at the chords. So maybe just follow the pedal part and memorize the hand part. Vidas: But, this part is not too fast. It should not be very fast. Ausra: Well, yes, because with 32nds the tempo is not that fast. It's not like Prestissimo, you know, on 32nds. Vidas: The first part, Très vitement, is very fast. Ausra: Right. Vidas: You have to be careful and play with good articulation. Ausra: Sure. Vidas: Sometimes people miss that by playing everything legato. And the second movement is Gravement, and it's so slow, right? So that everything is, again, legato. And it's a mistake, actually. You have to play all those intricate syncopations and difficult rhythms in the middle voices, as well as in outer voices with good articulation. But in the last part, it's not too fast. So, as Ausra says, slow down and memorize. Memorize one passage at a time, right? Ausra: Yeah. And I'm still thinking about that middle section, that it shouldn't be so slow, because actually the metre is cut time. So you have to have only one accent, one strong beat per measure. So this will give the feeling of a flow, of a general flow. Vidas: Exactly. But this is for later stage of practicing. For now, still keep counting in four and practice a little slowler. Ausra: Yes. Especially that last section. And actually opening section, too, because it's very easy to overwork on those spots if you are playing fast, and then you will never be able to correct them. Vidas: Yeah. That's a common problem with fast passages. Your fingers can play faster than your ear can grasp the meaning of the passage. Every time you practice, every time you play, you have to hear what you're playing. Listen exactly. Ausra: Yeah. And in that last section, just listen to all those beautiful dissonant chords. They are so important. Vidas: Okay. And perhaps, yes, try to write the chords down above the staves. Maybe, write down abbreviations of chords, not entire chord, but the meaning of the chord itself. Ausra: Sure. Vidas: Right. And that will be helpful, too. So guys, please send us more questions. We will love helping you grow. What's the best way to connect with us, Ausra? Ausra: To subscribe to our blog at www.organduo.lt. Viads: You enter your email, and become a reader of our blog, and you get those daily messages with current podcast episode, and later advice, and you can reply easily, and we can help you go. That's great. So, thanks guys. This was Vidas. Ausra: And Ausra. Vidas: And remember, when you practice ... Ausra: ... miracles happen. By Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene (get free updates of new posts here) Yesterday I was teaching my Harmony for 10th graders class and this one student struggled with passing and neighboring 64 chords. Then assignment was to harmonize a simple 8 measure melody in the soprano with 4 part harmony using root position, 1st inversion tonic, subdominant and the dominant chords as well as tonic and subdominant neighbor 64 chords and tonic and dominant passing 64 chords. I always joke that these 64 chords are the first thing they can use even being relatively inexperienced with harmony to make an impression of advanced and beautiful chord progressions. Enjoy the video I made about them. By Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene (get free updates of new posts here)

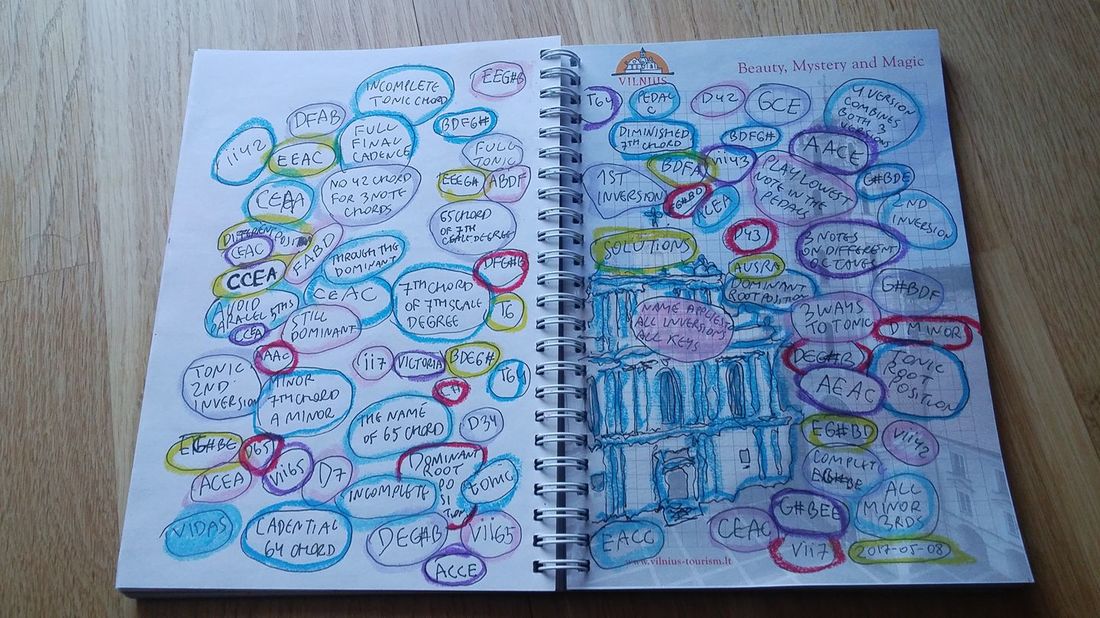

Yesterday Victoria asked me to teach her about the 7th chord of the 2nd scale degree in minor keys. As I was going through all the different inversions, one of the prevailing questions was why this beautiful 4-note chord has so many resolutions? You see, technically we only use resolutions which you can find in real music. So, can you find a usage of this chord which resolves directly to tonic? Of course, this is very simple. But you have to double the third so that parallel fifths would be avoided (In A minor: BDFA-CCEA). What about going from ii7 to the tonic through the 3-note dominant chord? Yes, and then you have to triple the root of the dominant and make this chord incomplete (BDFA-EEEG#-ACEA). Can you resolve it to tonic through the 4-note chords (either inversions of D7 or vii7)? In the case of D7, two voices are moving by step and two are stationary (BDFA-BDEG#-ACEA). With vii7, only 1 voice is moving (BDFA-BDFG#-CCEA). What if you wanted to make it a resolution through BOTH D7 and vii7? Then you simply move one note at a time (BDFA-BDFG#-BDEG#-ACEA). You can also have the 5th resolution through altered 7th chord. Then you simply raise the 4th scale degree (BDFA-BD#FA-EEEG#-ACEA). Does it seem complicated? Sure it does. But the point is to resolve to tonic either directly or through the most common dissonant 3-note and 4-note chords. After you understand it in theory, play it in practice in all major and minor keys. As always aim for at least 3 correct repetitions in a row. Do you want to know if you're on the right path of your practice? Find an extra pair of ears/eyes that you trust and ask for feedback. Hope this helps. |

DON'T MISS A THING! FREE UPDATES BY EMAIL.Thank you!You have successfully joined our subscriber list.  Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas

Authors

Drs. Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene Organists of Vilnius University , creators of Secrets of Organ Playing. Our Hauptwerk Setup:

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

This site participates in the Amazon, Thomann and other affiliate programs, the proceeds of which keep it free for anyone to read.

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed