|

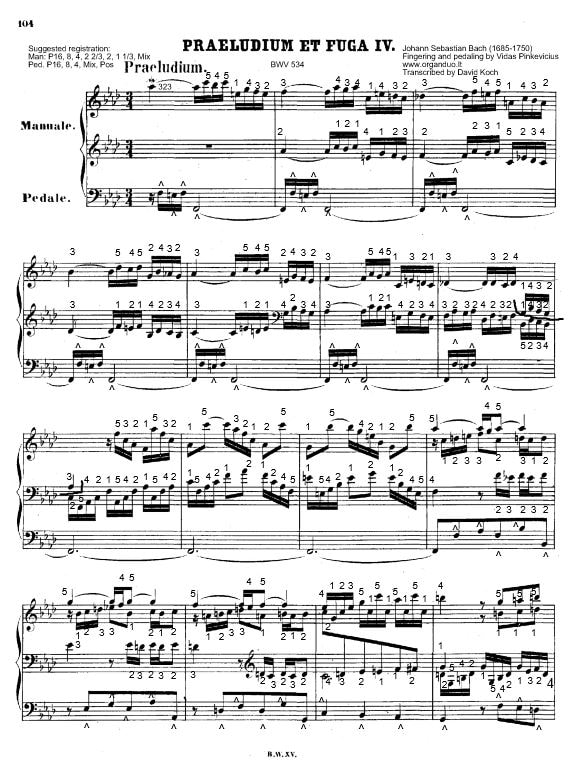

Would you like to master Prelude and Fugue in F Minor, BWV 534 by J.S. Bach? I have created this score with the hope that it will help my students who love early music to recreate articulate legato style automatically, almost without thinking. Thanks to David Koch for his meticulous transcription of fingering and pedaling from the slow motion videos. Advanced level. PDF score. 8 pages. 50% discount is valid until June 7. Check it out here This score is free for Total Organist students. Bellow are my practice videos in slow motion:

Comments

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

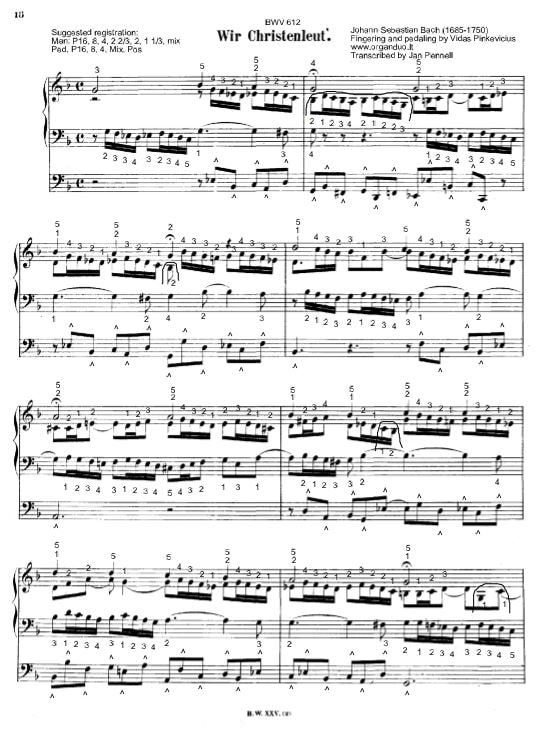

Ausra: And Ausra. Vidas: Let’s start Episode 225 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. This question was sent by Steven, and we are continuing our discussion about what makes a good free theme, let’s say for a prelude, because in a previous podcast we talked about the fugal theme. So let’s look at our example of BWV 541, Prelude and Fugue in G Major by Bach (and we discussed the fugue in the previous conversation). And the theme, of course, doesn’t start right from the beginning, right? It’s a flourish--it’s like a passagio, right Ausra? A: Yes, and you know, in terms of talking about preludes, it’s so distant from the fugue. V: Mhm. A: It’s completely different, because the main purpose of the prelude is to set up the key for the fugue. So it very often has a more improvisatory character. V: Mhm. A: Or, you know, more virtuoso character. It can be like a toccata. V: Mhm. A: And I don’t think you have to create a specific subject to the prelude, because it’s not a fugue. V: Maybe you could use several rhythmic elements to create certain episodes. Because with Bach--later in his life, when he matured and studied works of not only German composers like Buxtehude, but also Italian composers, like Vivaldi--he created what we call ritornello prelude. Remember, this recurring melodic idea which could be found throughout the prelude in various shapes: in the original key, in other related keys, in shortened or expanded version--it works as concert material for the entire prelude. A: Yes, but you are now talking about more sophisticated preludes, more complex preludes. V: Mhm! A: And I’m talking about simpler ones. V: Uh-huh. A: You know, I’m not talking about what you just meant, like Prelude in E♭ Major! V: With 3 episodes! A: Yes, with the 3 episodes. But in terms of when I’m thinking about preludes: just imagine that you come to a strange instrument, that you see for the first time--a strange organ; and you sit down on the organ bench, and you want to… V: Try it out. A: To try it out. V: Mhm. A: For me, that’s what a prelude is about. V: It’s an introduction to the fugue. A: True. V: In this case, then, what you need to think about is a tonal plan. A: Sure, sure. V: Maybe one--just one--melodic, harmonic, and rhythmic idea which you could use in various keys. Right? For example, let’s take the first prelude from the Well-Tempered Clavier. The fugue is very complex-- A: Yes, it’s one of the most complex pieces. V: With 4 parts, and many canons; but the prelude is so simple that it starts like arpeggiated chordal action. A: It’s like basically a long cadence. V: With the cadence in G Major, which means in the dominant key? A: Yes. V: Then, I think it goes to d minor--to what, the second scale degree chord or key; it might touch, of course, the relative minor, which is a minor; and towards the end, it has what--dominant pedal point. A: True, and then it resolves to tonic. V: Tonic pedal point at the end, with an excursion to the subdominant key, and plagal cadence. A: But it has all the same figures over and over again, throughout the entire piece. V: Yes. That’s plenty for an entire prelude. It is, of course, a shorter prelude; for more sophisticated writing, this could be just the first episode, right? A: Could be, yes. V: Maybe a little bit long, but half of it could be for the first episode, and you could actually...actually, you could take 3 of Bach’s Preludes from the Well-Tempered Clavier with the same meter and use the same figures in alternation to create something similar to E♭ Major Prelude by Bach, BWV 552/1. A: True, and of course, when you select your key for your prelude, you could also think about the message that that key brings to you or to the musical world V: Mhm. A: Because I’m thinking about the same C Major Prelude, and then the c minor Prelude from the Well-Tempered Clavier Book I---how different they are. Remember the second, that c minor prelude, how dramatic it is? V: Well, yes; it’s like a toccata. A: Yes. It’s definitely like a toccata. Fast motion all the time, very virtuosic. V: But also no imitations, no fugal elements-- A: True, true. V: Just simply arpeggiating those chords between 2 hands. And the same is with d minor, probably. Some of the preludes I remember from Well-Tempered Clavier, like E♭ Major, it already has imitations, so it’s more advanced writing. And Bach loved to create imitation episodes within the prelude, too. A: True. V: Like in c minor Prelude and Fugue for the organ, BWV 546. A: Because that’s a good technique to develop your piece, to make it longer. V: And more interesting. A: True. V: Because when you write imitations, it’s like a dialogue between the 3 parts. A: Plus, all those imitations come with sequences, too. Sequential episodes. V: Yes. So, sequence is what? It’s a technique to connect various keys, basically. A: True. V: To bridge the gap between C Major and G Major, you add a sequence going downward and adding somewhere F sharp. A: That’s right. V: The new accidental of the new key. So things like that comprise a prelude, or basic prelude type of writing. It could be called sometimes Fantasia... A: Sometimes Toccata... V: Sometimes Toccata, if it’s a motoric piece...But mostly, it’s one and the same: free writing, not based on a fugal theme. If you have your fugal theme ready for you, and you created the fugue, you could simply select the key of the same fugue and maybe create a different meter: if your fugue was in 4/4 meter, maybe the prelude could have 3/4 meter, and vice versa. Or the same meter, could be. A: Yes, I think. V: But maybe different tempo. A: Sure. V: And then think, sometimes, how the tempo relates to the prelude and fugue. What is the relationship between the tempo--sometimes there is... A: Yes. V: And most of the time there is. A: And it’s the sort of subject that always makes so many discussions and arguments, because everybody has their own truth. V: Yes, yes. So for starters, avoid complex metrical relationships; maybe use the same meter for the beginning, right? For your first 10 fugues and preludes. A: Yes. V: Mhm. A: That’s what I would do. V: Excellent. And to make it more interesting, use excursions into related keys. In a major key, you could modulate to the second scale degree minor, third scale degree minor, fourth scale degree major, fifth scale degree major...What else? Sixth scale degree minor. A: True. V: That’s the most common type. What about a minor starting point? A: That’d be just the other way around. V: For example? A: You would have third scale degree major, and sixth scale degree major. Then, of course, fifth degree would be major, too, but the first scale degree would be minor. V: You said major fifth scale degree? A: Yes. V: Why? A: Because the fifth scale degree is mostly major in both minor and major keys. V: So if a starting point is a minor, the fifth scale degree would be…? A: E Major. V: E Major. Can you use e minor, then? A: Well, yes, you could. This wouldn’t be so common, but you could do it. Of course, it would have a different meaning. V: So the same as with first scale degree minor? A: Yes, because you know, if you use the minor dominant in a minor key, it means that you don’t have a dominant chord. It means that you have a subdominant. V: But I’m not talking about the chords. I’m talking about the episodes. A: But these are all related, too, with the harmony. Don’t you agree? V: What about… harmonic subdominant? Remember, a minor first scale degree chord--in a major key. Can it be used? A: Yes, I think... V: It is related. A: Yes, it is related. V: Just like a major dominant in a minor key... A: Yes. V: Then minor subdominant in a major key. A: Yes, because you know, what I’m thinking is: for example, in a minor key, if you would use the episode in E Major, then you could have the tonic straightaway after the dominant episode. V: Mhm. A: E Major episode. If you would use an e minor episode, then probably you wouldn’t go back to the tonic episode. You would probably have to use something from the subdominant material. V: Okay, guys. This was our discussion about creating a prelude; and as you see, the most important thing is to choose a fun rhythmic, melodic, or harmonic figure, and keep it throughout. And by the way, I teach this technique in my Prelude Improvisation Formula, which is based on the Klavierbüchlein for Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, the preludes that Johann Sebastian Bach created for his eldest son. So people who want to learn to improvise like that, in a free style--they can train from this collection as well. Okay. And please send us more of your questions; we love helping you grow. This was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: And remember, when you practice… A: Miracles happen. Would you like to master Wir Christenleut, BWV 612 by J.S. Bach from the Orgelbüchlein? I've created this score with the hope that it will help our students who love early music to practice efficiently and recreate articulate legato style automatically, almost without thinking. Thanks to Jan Pennell for meticulous transcription of fingering and pedaling from the slow motion video. Basic level. PDF score. 2 pages. 50% discount is valid until June 5. This score is free for Total Organist students. Bellow is my practice video in slow motion: Secrets of Organ Playing Week 5 is open. The deadline is Monday, June 4 at 12:00 PM UTC.

Here are the details for entering. We have four categories: 1. Organ Repertoire 2. Hymn Playing 3. Organ Improvisation 4. Organ Composition I'm sure everyone will find something which would be interesting. Hope to see you on the inside! Congratulation to the winners of the previous week! Please click on the above link if you want to hear their improvisations. Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

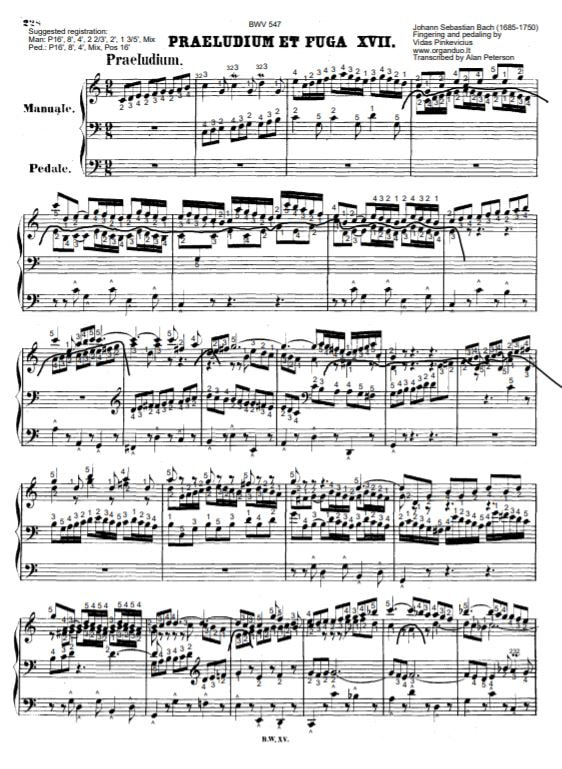

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start Episode 224 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. This question was sent by Steven and he writes: It would be an extremely interesting subject some time for a podcast, if you and Ausra might consider discussing what the elements of a good free theme and a good fugue theme are, as regards development. All the best, Steven V: So Steven he frequently composes various organ compositions and he likes to create preludes and fugues out of free themes not based on a chorale melody and he wants basically to know if there are any themes that are unsuitable for musical development or are any themes suited better than others. So of course we could take examples of masterworks by various composers, right Ausra? A: True, yes there is so much music written. V: And when you play those pieces Ausra do you notice that those melodies have something in common. A: (Laughs) Of course all the musical melodies we have something in common and that’s the music notation and intervals, certain intervals. V: So which intervals basically are not very good for developing a theme in a prelude or a fugue. Perhaps intervals which are difficult to sing? A: Yes, I think big leaps maybe are not so suitable and not so common although you could encounter them as well. But in general when creating a subject or a theme for your piece you need to know how will it sound if you will invert it. Because especially in fugues the technique you use is called invertible counterpoint. V: Exactly. For example right now we are looking at Prelude and Fugue in G Major by Bach, BWV 541. And the fugue lends itself very well for the canon because it has intervals of ascending fourths and ascending sixths and when you do that at a certain interval you get a nice strata so every good fugue usually has a strata, but not always, but composers tend to seek out elements of their theme that would be suitable for that. A: Sure. Right now I’m thinking about the C Major fugue from Well Tempered Clavier, Part 1. It has a very nice steata at the end of it. V: And basically this is a scholastic fugue because in almost every measure you can find appearances of the theme and in various ways as you say, inverted, and in canon and composer created this fugue specifically out of this theme and every measure is based on the theme basically. So whatever you do in your fugue you should always think about the theme and of course countersubject. A: True. V: Is countersubject important Ausra? A: Well, it’s of course important but probably not as much as the theme because what you do with your theme that you actually need to have it throughout the piece. V: Um-hmm. A: And whatever changes you do we can not go very far from the theme. You could do it augmented or diminished. V: Um-hmm. A: In long note values or in the short note values but basically you still keep the same interval structure. But what you can do with the countersubject, actually in some fugues the countersubject is kept throughout the piece and actually that’s a very high level of polyphonic composition if you keep the countersubject the same throughout the piece. But in some pieces it changes all the time, slightly or even more. V: They say that’s it’s easier to compose a fugue with changing countersubject that with fixed countersubject. A: True. I believe it. V: And we could analyze a theme or a countersubject based on at least three elements, melody, harmony, and rhythm. And every melody, every subject, and countersubject should have those melody rhythmic elements and harmonic elements well fixed and well developed and encoded basically so that you could develop your piece entirely based on those three melodies. Let’s say we take a look at the theme of the G Major Fugue by Bach. And the melody it has nice intervals, right? And it has a nice range. It doesn’t exceed an octave. That’s usually. A: Yes, that’s usually the case even I would say that most of the fugues are, the theme are not exceed more that a sixth interval. V: Except in a minor mode they allow a diminished seventh. A: True. V: So then here in G Major Fugue we have a range from D to B, this is a major sixth, that’s about normal. A: Yes. V: If you have just a few notes of range like a minor third it’s a little too few notes, too few melodic intervals. A: True, then you will not have a chance to develop them. V: Maybe. If that’s the case your countersubject should be contrasting with wider leaps. A: True. V: So then of course melody should be singable. Basically you need to write those intervals and sing yourself. Can you sing that fugal theme yourself. That’s another reason we try to avoid augmented intervals. A: Yeah. V: And wide leaps above major sixth let’s say. What about the rhythm. What do you see here Ausra? A: Well most of fugue themes consist of eighth notes, quarter notes, some sixteenth notes. V: So whatever meter you decide to create you have to use the values that are suitable for that meter. A: True. V: Well some composers choose to use like triplets, special duplets, as they say, which is quite uncommon because then you mix duplets with triplets and in a fugal theme it’s not very often seen. A: True. I think it’s better to stick with common values such as eighth notes, quarter notes, sixteenth notes. V: Because with the countersubject if you do let’s say sixteenth notes or eighth notes and with the subject you do triplets you have a hard time of mixing them together as a performer. A: True. V: Um-hmm. Then it’s maybe better to change the meter altogether and write in a six, eight meter. What about the harmony? Of course a fugal theme is a melody for one voice. Of course we have sometimes double fugues where two voices enter subsequently one after another and then some harmony can be traced out of those two voices but it’s quite uncommon. If you are just starting writing fugues of course we recommend sticking to one theme. A: That’s right. But already I think you know that most of the Bach fugues could be analyzed in terms of harmonical chords. V: Definitely. Let’s say we have the stronger beats in 4-4 meter every two beats, we have a rather strong emphasis on the note and here we have to change the harmonies and let’s see how Bach does. The first measure has D and G so on D you could harmonize as the dominant chord of G Major, on G you could harmonize what? A: Tonic. V: Tonic. Then the second measure starts with the suspension basically F# is the main note. A: Yes, and you have the dominant again. That’s very common for opening stuff, any piece. Then you need to establish key and you use dominant, tonic. V: Dominant, tonic, dominant, tonic. And then the second chord is on the note D which is also a tonic obviously. A: Yes. There you also have some A note, this would be something of the dominant, yes. So basically this would be juxtaposition of dominant and tonic throughout the subject. V: Yes, and the second half of the third measure has noted G. We could harmonize it as the tonic also. And the fourth measure begins with the dominant function ending of the fugal theme. So in every measure we should have at least two chords. And sometimes sub-dominant too. Tonic, dominant, and subdominant they work well and remember we could have inversions, not only root position chords but inversions. So when you write a theme for yourself on a sheet of paper maybe write on two staffs on the higher staff you could write the theme and on the lower staff you could add the bass line. And this bass line might be the basis for your countersubject. A: True. V: Speaking of which, what is the difference between subject and countersubject right here in the second line. Are they similar or contrasting? A: I’m looking at it right now. I’m trying to decide. V: When the theme has eighth notes what does the countersubject have? A: Of course the countersubject has smaller note values. That’s very typical for countersubject. V: When the theme subject has smaller note values… A: Countersubject has the longer note values. V: Um-hmm. And vice-versa. Basically it’s a dialog between two voices. A: True. V: One is speaking and another is listening. A: Yes, because if everybody would try to speak at the same time you would have chaos. V: Um-hmm. And since we didn’t have any tied over notes or just one syncopation in the theme there are syncopations in the countersubject as well. More of them, right? To make an interesting rhythmic element. A: That’s right. V: But if we look at the melodic element of the countersubject it has this wide leap upwards an octave. Ausra, what does the subject do at that moment? It goes... A: down. V: Down. It’s an opposite direction. Always try to create a contrasting motion between two voices and that’s very good for making two voices independent. A: But you could also have parallel motion for example when the third voice will come in. And you will have the theme, the countersubject, and the third voice. V: Um-hmm. And by the way if you have three voices later on you could easily create a fugue with two countersubjects which are fixed and they are interchangeably connected and they could be inverted and used in various combinations and in various voices. This is called permutation fugue where soprano suddenly becomes the bass, alto becomes soprano, or the bass becomes alto or soprano. Any number of combinations. But then there is one caveat to avoid. What is the least used inversion of the tonic chord Ausra? A: 4-6 chord. V: Uh-huh. So we have to check that there is no such intervals as the fourth above the bass or the fifth above the bass because in inversion they would create fourths or fifths. Fifth in itself is good but fourth when you invert makes 6-4 chord so what do we use instead? A: 6th chord. V: And basically intervals of the thirds and sixths if you want to use this invertible counterpoint. A: And actually you know if you really want to compose fugues you have to study the fugues written by great composers and most famous collections probably would be Well Tempered Clavier by J.S. Bach, then probably if you want to study more modern style you could study Paul Hindemith’s Ludus Tonalis. V: And don’t forget Art of Fugue. A: Yes, Art of Fugue of course but that might be too complex maybe, don’t you think so? And another composer probably would be Dmitri Shostakovich, also his 24 Preludes and Fugues. V: In a modern style. A: Yes, in a modern style. I think he also got his inspiration from J. S. Bach. V: Um-hmm. That’s right. If I remember correctly Prelude and Fugue in C Major doesn’t have any accidentals at all. A: I think so, yes. V: White keys only. So that’s the start right? So not every melody is suited for fugal development. A: Maybe you know if it’s hard for you to create your own theme for a beginner you could pick some of these composers themes and try to create fugues. V: Um-hmm. What about prelude? Prelude of course it’s another story. Maybe we could leave it for another conversation in next podcast, right? Maybe we should start it with the prelude but since we started with the fugue now prelude comes later. OK guys, this was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: And remember when you practice… A: Miracles happen. Would you like to master Prelude and Fugue in C Major, BWV 547 by J.S. Bach? I have created this score with the hope that it will help my students who love early music to recreate articulate legato style automatically, almost without thinking. Thanks to Alan Peterson for his meticulous transcription of fingering and pedaling from the slow motion videos. Advanced level. PDF score. 8 pages. 50% discount is valid until June 3. This score is free for Total Organist students. Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start Episode 223 of Ask Vidas and Ausra podcast. This question was sent by David, who is helping us transcribe my slow motion videos into scores with fingering and pedaling. And he writes: I'm getting better at this, yes. I'm quite enjoying this. I have an organ transcription for BWV 35, the aria Gott Hat Alles Wohlgemacht. I've been adding the fingering as I go, but with the work I'm doing here, I've been noticing things in the fingering that has got me going back and analyzing the entire aria and I've revamped the fingering in certain areas and I'm actually writing it in for every note while testing it at the same time to make sure it makes the most sense. I have a good grasp of the pedals, but with some of what I've noticed you do, I'm now applying those techniques and it's starting to catch on with the basic hymn playing I do. Sections that I used to find a bit challenging to figure out the proper pedaling before are now becoming a breeze! What can you say, Ausra, about this feedback? A: Well, I appreciate David’s letter! It’s so good to know that things that we are doing, that you are doing, are actually working. But it just proves what I believed starting from, I don’t know, 20 years ago, that right pedaling and right fingering may solve a lot of problems---technical issues, V: Mhm. A: and will make playing much easier. V: And you see, I am reading actually in between the lines, now, what David wrote, because he’s watching the videos and transcribing the fingering and pedaling into the score. He learns my technique, too! Not only does he help me, but he helps himself. A: True! V: Right? And later, he can apply my own system, or our own system, because it’s similar, in his own performance, which takes him, basically, to another level. A: Because it’s often the case, if you are working on a new piece, and there are some spots or one spot where you cannot play correctly---you always make mistakes, you always mess something up---then probably, your problem is incorrect fingering or pedaling. V: Either incorrect fingering and pedaling, or inconsistent pedaling or fingering. A: Yes, True. V: Sometimes people don’t bother writing them down, and play with whatever accidental fingering and pedaling they want. And that’s not consistent. And imagine, in one rehearsal you play one way, in the second rehearsal you play the second way, in the tenth rehearsal you play the tenth way, and in the public performance, you mess it all up, because you are in a very confused state. Especially with public performance, it’s dangerous; you’re stressed, and you don’t have motor skills this way. A: That’s true! And, this just reminded me, I almost started to laugh. When I had an open lesson of music theory with my ninth-graders a few years ago. And there were like three people watching that lesson. V: Mhm A: It was for me to receive a certain certificate. And, one of my students was playing just a basic sequence. And he suddenly said “Oh, I don’t have enough fingers!” And then another guy who always makes jokes said, “Oh, take my finger, then you will have six in one hand!” And everybody was just laughing. And the problem was related to this, because he chose the incorrect fingering, and then he could not play the chord appropriately. V: And sometimes you can use both hands... A: True, true. V: ...to facilitate playing of sequences like that. So even kids sometimes, in a way, understand the need of fingering the hard way, basically while making mistakes like that in front of the public. It’s sometimes humiliating, right? A: Yes V: Because he wasn’t joking, right? A: I know! V: Others were joking! A: True. So yes. Do you feel sometimes that you would need to have a sixth finger? V: If I do, then I need to add my foot, you know, like a third hand. And in a way, our feet are sometimes designed as a third hand. We use them, both feet together, as one additional hand, sometimes. While keeping heels and knees together, they move together as a unit, right? And not two separate limbs, but just one. Except, in cases where there is a double pedal passage, which is rather rare. A: True. V: Do you recommend, Ausra, writing down fingering themselves for people who don’t know how to do it? A: Well, I would say you’d better learn how to do it and then write them down. Otherwise, you might need to rewrite them a few times. V: Can’t you learn by doing? By writing and making mistakes, failing, erasing, and adjusting? A: Yes, that’s one way, but that’s a longer way. That will take a lot of time. So having correct fingering at the beginning, I think would save you time. Unless you like writing and rewriting fingering all the time. V: Another person who is on our team of fingering and pedaling transcriptions, he asked me to provide a score, you know, from which I’m playing, with fingering and pedaling. He hoped I had a score with fingering and pedaling written in with pencil. But I said, “No, I’m just sight reading those pieces with correct early fingering and pedaling right away!” And he asked me how is it even possible, right? Well, A: After many years of, you know… V: The first 20 years are difficult. A: Yes. Daily training and then it’s easy! V: Once you learn the system, you can do many, many things right away without preparation. And actually, one of my goals with sight reading those fingerings and recording those videos is not only to provide material for our team to transcribe, but also to improve my own sight reading, because it’s a process, right? It always improves or degrades depending on if you miss practices or not. So I hope to improve to the level that I can learn my pieces faster and faster. And sometimes, it’s even sight read unfamiliar pieces, easy pieces, during public performances in a fast tempo, concert tempo, if you reach that level. A: Yes. I think it’s always important when you are trying to teach other people, to help other people, don’t forget that you have all these to be improving yourself as well. Because otherwise you will not be able to teach others. V: Oh! Isn’t that a nice circle? While teaching others, you are teaching yourself as well. A: Yes, it is. V: And while teaching yourself…. Actually, you are not always teaching others, right? People who are hiding their talent from others, they are not helping others. But that’s another side of the story. We prefer to be open about it, right? We learn something new and we share with the world. A: Yes. V: Ok, thank you guys for sending us questions. We love helping you grow. And we hope that you apply our tips in your practice, and continue to develop your own skills in whatever area you choose. This was Vidas, A: And Ausra. V: And remember, when you practice, A: Miracles happen. Would you like to master Lobt Gott, ihr Christen allzugleich, BWV 609 by J.S. Bach from the Orgelbüchlein? I've created this score with the hope that it will help our students who love early music to practice efficiently and recreate articulate legato style automatically, almost without thinking. Thanks to Jeremy Owens for meticulous transcription of fingering and pedaling from the slow motion video. Basic level. PDF score. 0.5 pages. 50% discount is valid until June 1. Check it out here This score is free for Total Organist students. Bellow is my video in slow motion of this piece: Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

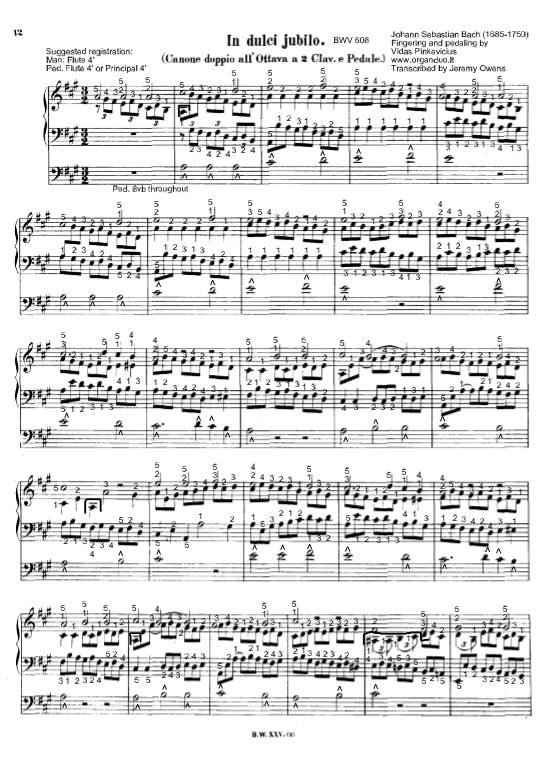

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start Episode 222, of #AskVidasAndAusra Podcast. This question was sent by Samuel. And he struggles with recognizing patterns in the form of chords, completely and independent, and sight reading harmonies, especially hymns. V: Ausra, I think most of his struggles are related to chords and harmony skills, right? A: Yes. V: It’s not an easy skill to develop though. A: True. True. V: It takes perseverance and time. A: That’s right. V: Where should he start? What’s the first step, would be? A: Ah, probably he has to take some music theory. V: Basic music theory training, like our basic chord workshop, where I teach the chords and inversions of three-note chords, and four-note chords, even the ninth chord which is a five-note chord. A: True. V: Afterwards, he will be ready to go into probably more advanced harmony. A: Yes. V: Playing with two hands, not one. A: That’s right. And first of all you just have to start to recognize chord patterns. When you look at the score, and only after a few years, you might recognize while playing. V: I remember John from Australia in our long-term correspondence wrote a few times that he, after studying those chords in theory, he started to notice them in practice, in his compositions that he’s playing. But little by little, maybe not even in compositions but especially in hymns. A: True. V: At first. He said “oh, it’s a dominant chord”. Or, “oh, it’s a modulation. That’s where we have F sharp”. You know, things like that. Little by little, the new world starts to open up for him. A: True, but it’s a slow process. And anybody who has to spend quite a bit of time with it know that. V: Of course, it’s different for everyone. For us it was systematic training and we spent twelve years studying at the national level, art school, right? Where each grade we had to, to study ear training, and then later music theory, and then later harmony. So, do your remember back in your childhood, Ausra, were you conscious of those harmonies in your pieces that you were playing? A: No. Not at all. Because we receive a professional training in all those music theory disciplines. I think that the main mistakes and the weakness of our school training was that we very rarely applied them here in practice. Somehow these two, performance and theory existed on their own. And only later on when I became an adult, I myself started to draw conclusions and to search for a right way, or better ways, combining theory and practice. V: The same for me. I think the first piece that I played on the organ that was one of the chorale preludes from Orgelbuchlein, and I think it was "Jesu, meine Freude", BWV 610, by Bach. I was worrying about putting hands and feet together but not about chords and how the piece is put together. A: Yes. But I think understanding that composition with structure and seeing the meaning and the notes is very important. V: Especially when we teach adults. They have more developed sense of motivation. A: Yes. And especially when you are playing like chorale based works, because we also have a text somewhere, beneath those musical notes. And that also changes a lot. V: Sometimes you can even ask why is this chord, colorful chord here, and discover because of the text. A: True. So it is important to know what you are playing and to understand chords. V: Mmm, hmm. It’s good that Samuel is interested in that. Somehow it’s not a universally loved thing, an analytical approach to music. A: And it’s just too bad, because it we would look at the middle-ages when the university system started, started going in, in Europe, actually music was a subject of science. And it was taught together with math. V: Exactly. There is even a quote, a very famous quote about musicians and, and probably people who can understand music which is called ‘Musicorum et cantor magna best distantia’. A: could you translate it for everybody to understand? V: I’m trying to look up, yeah. Between musicians and singers, it’s a great distance. Which reads in Latin (This is the quote by Guido D’Arezzo. And I found it in Christoph Wolff’s book “Johann Sebastian Bach: The Learned Musician”.): Musicorum et cantor magna est distantia Isti dicunt, illi sciunt que componit musica Nam qui facit quod non sapit diffinitur bestia. A: And let tell couple of words about Guido D’Arezzo. V: OK. A: He was actually very famous for creating the musical notation system. So this is really one of the most, most important names in the history of music. So you need to, to know who he is. V: Exactly. He created the system that we use today, the solfege. A: Yes. V: So let’s translate this passage by Guido which is cited in Christoph Wolff’s book about Bach, which everybody interested in Bach’s music should read. And it, it goes as follows: “Singers and musicians; they’re different as night and day. One makes music, one is wise and knows what music can comprise. But those who do what they know least, ought to be designated beast”. A: These are strong words. V: In Latin beast is bestia. A: Yes. V: So, the meaning of this passage is basically, the person who doesn’t understand what he is doing is like an animal. A: (Laughs). Wow! V: Right? A: Well, V: In those terms. A: That’s a strong words. I would not put them like that. V: But that’s what Guido in the Middle Ages wrote. A: I know. V: Right? It’s… A: Way back. V: It was like a satire, right? Humor a little bit. So, but it just means that how this ancient, centuries old battle, between musicians and singers, between scholars and, and performers, went all the time. A: True, and I think that’s a nice quotation that Christoph wrote, chose for his book that he edited about Bach, ‘The Learned Musician’. Because in that book all the articles, they just help you to discover or to rediscover Bach and to show behind his scores, what he really did and how fascinating his music was, full of all those symbols and entire different world. V: Yeah. So although Samuel’s interest in chords is, is not perhaps related to Guido’s quotation of course. Not at all. He’s just is interested in knowing and recognizing chord patterns, just intuitively. It says that it’s extremely important too, for everyone who’s listening to this, to understand the meaning of, of those chords and structures, how the piece is put together. Basically, this is the preliminary step before you start to create your own music. And let’s face it, not everyone is willing to create his or her own music, right Ausra? A: True. V: And one of the reasons, I guess, I suspect is, that it’s not because of talent or lack of talent. Not at all. It’s because lack of knowledge. Lack of knowledge how those master, master works were created in the past, which could serve as models for us today. We should not of course copy them today, note by note. But use ancient techniques in a new way; combine and mix them together and create some new and original this way. A: That’s right. V: So I think, even though, Samuel doesn’t probably even aware, isn’t aware of, of, of this further steps, but his motivation to learn chords will definitely lead him into a realm of creating music too. Either on paper or on the instrument as in improvisation. A: Yes. Isn’t it wonderful. V: Absolutely. Amazing world! Every day you can learn something new from the treasury of organ music. And we wish you that. And please send us more of your questions. We love helping you grow. This was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: And remember; when you practice… A: Miracles happen! Would you like to master In dulci Jubilo, BWV 608 by J.S. Bach from the Orgelbüchlein? I've created this score with the hope that it will help our students who love early music to practice efficiently and recreate articulate legato style automatically, almost without thinking. Thanks to Jeremy Owens for meticulous transcription of fingering and pedaling from the slow motion video. Basic level. PDF score. 1.5 pages. 50% discount is valid until May 30. Check it out here This score is free for Total Organist students. Bellow is my video in slow motion: |

DON'T MISS A THING! FREE UPDATES BY EMAIL.Thank you!You have successfully joined our subscriber list.  Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas

Authors

Drs. Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene Organists of Vilnius University , creators of Secrets of Organ Playing. Our Hauptwerk Setup:

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

This site participates in the Amazon, Thomann and other affiliate programs, the proceeds of which keep it free for anyone to read.

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed