|

Vidas: Hi guys! This is Vidas.

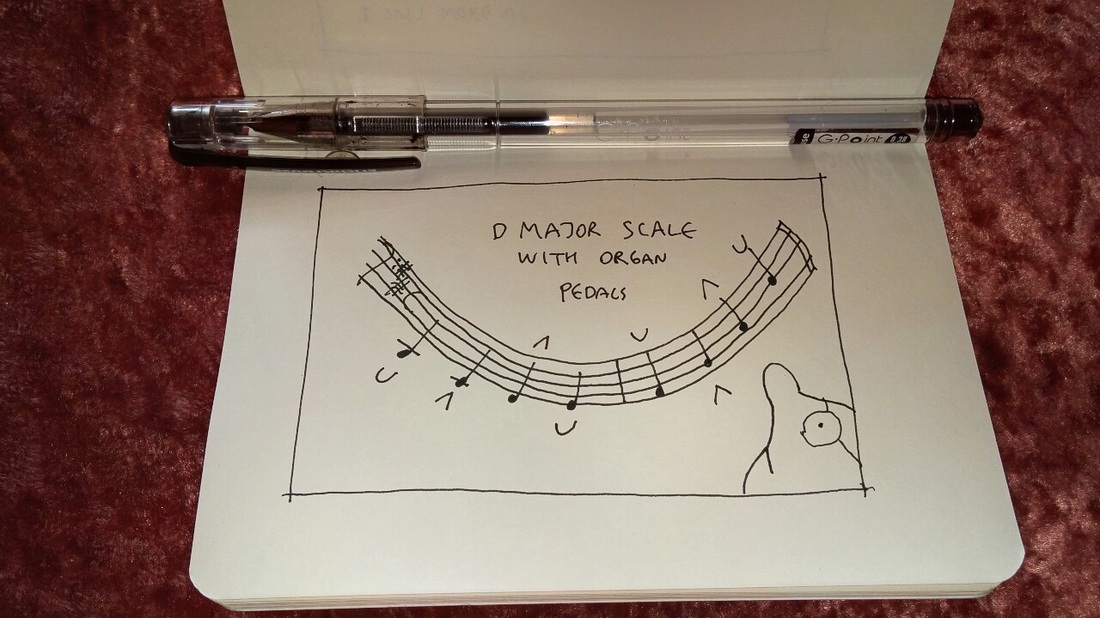

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 568 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Paulius. And he writes, Hello! Vidas, do you have the pedaling of D major scale in the Baroque style? Paulius Vidas: L L R L R L R R D E F# G A B C# D R R L R L R L L D C# B A G F# E D V: Do you know what he’s talking about, Ausra? A: Who doesn’t know the famous prelude by J.S. Bach? V: Do you think that he… A: With passage of D Major scale in the pedal. V: Do you think that Paulius is playing this piece himself? A: I don’t think, I think he is asking how to pedalize the scale for his colleague and friend. V: Uh huh. Could be. A: It’s sort of very interesting sounding when you are asking people for other people. V: Yes. I would suspect that, too. You know, Lithuanians sometimes, they never ask us questions directly, or never truly engage with our content online. Have you noticed that? A: Yes. V: I’m sure they can read English, or understand English, or hear our voices. We don’t talk complicated English, they could understand most of it, right? Plus, it’s organ-related stuff, so it’s not that difficult. But for some reason, Lithuanians, I would say, ignore us, right? A: Well…. V: Or not? A: That’s, you know, envy. V: Envy? A: That’s always, that’s the main feature of Lithuanian folks, we are just very envious. V: Mm hm. For people who are more successful than them? A: Well, yes, I guess maybe even for people who are different. V: Mm hm. A: Who think outside of the box. And see outside of the box. V: Sure. And we are not talking about Paulius now. A: Yes. Definitely not. V: Paulius is our friend. So, playing D Major scale. I suspect it’s for D Major Prelude and Fugue, BWV 532, and the principle that I usually apply here, I hold this principle for every baroque piece, every baroque, up to, let’s say, 19th century. So, I don’t play everything with one foot, or with another foot, or with heels. The system is that you use alternate toes whenever possible, left-right, left-right, left-right, or right-left, right-left if in descending motion. But there are exceptions. Sometimes you play with the same foot. And the system was described in very easy terms by Harald Vogel in his preface, I think, to Tabulatura Nova by Samuel Scheidt. And I read it, and it made sense. Then later, of course, Richard Stauffer Organ Method book applied this extensively, and that’s where we had learned our early technique from. A: So basically, it’s common knowledge for people who are thinking about historical performance, or accuracy of historical performance. V: Mm hm. So, you play with the alternate toes, right-left, right-left, most of the time. But play with the same toe, same foot twice, let’s say, when there is change of direction, if the melody moves upward and then downward, you play with the same foot. Or, when there are longer note values, you can play with the same foot if there are half notes, let’s say. It’s nothing to worry about, you don’t have to play in alternate toes unless you want. And you play with the same toe when there is an upbeat before the stronger beat. It doesn’t have to be beat 1 of the measure; it can be beat 3 in 4/4 meter. Or in faster notes, like sixteenth note passages, like in D Major scale, it could mean every, it could be, the first note could be played with the same toe. D, E, those 2 notes of the scale, I would play them with left-left. And then alternate toes. It would be left-left-right-left-right-left-right-right. Because the last note is the strongest beat. Does this make sense, Ausra? A: Yes, and because the last 2 notes are already very high up… V: Mm hm. A: On the pedalboard. V: Of course, in this piece, there is no descending scale, but I wrote to Paulius anyway, I would start the same way, but from the right toe. Right-right-left-right-left-right-left-left. A: It makes sense. V: So, ascending will be D E F# G A B C# D, Or left-left-right-left-right-left-right-right. And descending will be D C# B A G F# E D, or right-right-left-right-left-right-left-left. Would you do this the same way, or a little bit different? A: Yes, I would do it the same way. I think it’s very adequate. V: This is not the same if you want to play D Major scale legato, in a modern style. A: Of course. It would be completely different. You will use heels as well. V: I would play, I would start with the heel, D, then the toe of the same foot, left foot, E, then F# would be right toe, then G would be left heel, A would be right heel, and then B would be left toe, C# would be right toe, and then heel on D. It’s like a heel, toe, toe, heel, heel technique mostly. You keep your heels together. That’s very easy then. Does it, is it something you would apply yourself, Ausra? I see your hidden smile. A: Well, you know, if you would have such short legs as I do, I don’t think you would be able to keep all time your knees together. So that’s, you know, we have different physiology. And for example, if I would have to play in romantic style, the D Major scale, the three upper notes I would play with my right foot. I would do the heel on the B, then the toe on the C#, and then finish with the heel. V: I see. You need longer legs. A: Yes. Could you buy them for me? V: Um (laughs) good question! I’m just looking at YouTube videos that I did, and it looks like my video on how to play the C Major scale with pedals on the organ has 75,000 views. It’s my most viewed video. But, D Major scale, D Major pedal scale has, guess how many views? A: Less than C Major of course. V: How much less? A: A lot. V: Only 4,737 views. A: Very few people care for D Major scale. V: Yes. It pays to play with zero accidentals. So, you can look it up, by the way, if you are interested in looking at my feet and seeing how I play D Major scale. But this is in legato style. A: Yes, definitely. So you would not apply it for playing… V: Mm hm. A: Bach’s D Major Prelude and Fugue. V: And by the way, if you need guidance and you need to perfect your organ playing pedal technique, I really recommend Pedal Virtuoso Master Course. We have exercises in playing arpeggios and scales over one and two octaves, and what it gives is, provides you, helps you create, develop your ankle flexibility. And this is the secret sauce of having perfect pedal technique in any style, of course. It’s based on legato style, so it doesn’t work for toes only technique. But just think, just something to keep in mind if you want to perfect your pedal technique. It’s really worth it. Okay, guys. This was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: Please send us more of your questions. We love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice, A: Miracles happen.

Comments

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 274 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. And this question was sent by Henry, and he writes: Thank you so much for the first video you have just sent me Sir... My question is, what are the techniques for playing scales perfectly, how to play without looking the hands, how to look ahead and lastly how to prepare an organ practice schedule? V: So, Ausra, that’s quite a few questions, right? A: True! V: I’m not sure if we are able to answer them in detail, but let’s try. A: Okay. V: The first question was, of course, about playing scales perfectly. Remember the first time you tried to play scales, Ausra, in your life? A: Yes. I remember it. V: I don’t, so enlighten me. A: Well, I loved playing scales, actually, that was the easiest thing for me. And, I loved the scales exam, because you don’t have to memorize them, so it’s very easy. You just let your fingers run. But of course, I think the success of playing scales well is to play them with the right fingering, and the secret of it is to know when to put the thumb under. And if you know that, then it’s easy. Of course, it takes time. It takes, you know, a lot of practicing hours, but definitely, playing scales is not the hardest technique. V: And people who are interested in scales can pick up a volume of “Virtuoso Pianist” by Charles-Louis Hanon, and of course, in the second part of that collection, there are exercises in scales and arpeggios and chords, so that’s a good place to start. A: And of course, when you are playing scales, you need to know when to add accents, because, you know, if you are playing a scale in C major, it means that you have to accent each C note. Because otherwise, if you will not accent correctly, or if you won’t use accents, then probably you might lose the tempo and coordination between hands. V: Your hands will play not in time…. Not together, basically. A: Yes. V: For me, the difficult part in playing scales was playing in opposite direction with a few sharps and flats. I remember that. Especially minor scales. When melodic minor right hand goes upward with the 6th and 7th scale degree raised, at the same time, you have 6th and 7th scale degree normal, without sharps in the left hand in descending motion. And then they switch when the left hand goes up then the right hand goes down with those… A: Well, wonderful, I have never thought about it. V: It’s difficult. A: Somehow I played it automatically and never thought that it might be hard, but now when you’re saying this, yes. V: For me it was hard. A: It might be confusing in some cases. V: Right. So the next question by Henry is how to play without looking at the hands. Well, it takes, simply, practice, and obviously, knowing the patterns. A: Sure. I think it will come with time. For example, let’s say when I’m playing solo, I don’t have to look at my hands or at my feet. Well, occasionally, of course, I look, but rarely. For example, when I have to organ duets with you, then it’s more complicated, because sometimes you play the first part, sometimes I play the first part, and then we switch, and then you know, you have to sit a different position, a little bit higher or lower on the organ bench, on the left or the right side. And then, I think I need to look a little bit more, because the keyboard is shifted. V: Exactly. For me, I can play without looking, but then it’s confusing when you go from manual to manual. You have to check, sometimes. Or if you jump from octave to octave. A: True, so, occasionally, you have to look. But in general your goal is to learn to play in such a manner that you wouldn’t be looking at the keyboard all the time. V: And the best medicine is, of course, to look at the score in front of you. A: Sure. V: The next question is how to look ahead, right? Imagine a situation where you’re playing a piece of music, and where do you look exactly in the score? Which note, Ausra? A: Well, that’s a complicated question, because I remember since very early in my childhood, my piano teacher always telling me, “Look ahead! Look ahead! Think ahead!” And, I always thought, “How would you do that?” But, I would say that now, I’m looking sort of a half a measure ahead, or maybe a measure ahead. V: A measure ahead is a lot. A: That’s a lot. I would say half a measure, probably. But also, not on all occasions. V: If the tempo is fast, then a half a measure, maybe. Maybe it’s possible to look ahead, but if it’s a slow tempo, then maybe a quarter note ahead is okay. A: But you know, now, when I think about what my teacher probably kept in mind about looking ahead was not looking right ahead, but probably, knowing what is coming in the piece in its structure. For example, that you are getting to the end, let’s say, if you are playing a sonata, at the end of it’s position, or now you finish the first theme and the second theme will come, and knowing things like this. V: You mean, probably, knowing the structure and feeling the phrasing a little bit, which helps for the listener to also feel the structure of the piece. A: True. V: If you know the structure, then the listener feels the same. A: Yes, and I think that looking ahead comes easier when you know a piece well enough. V: Not when you sight read. A: Sure. The better you know your piece, the easier for you it will be to look a head. V: And the last question is how to prepare a schedule on organ practice. Basically, what he means, probably, is how to know what pieces to practice each session. Right? A: Well, it depends what you are working on. V: So let’s say you have 30 minutes of repertoire to prepare. A: Sure, and of course, I would suggest if you don’t have very strong technique yet, that you would do some exercise first—some technical exercise: scales, arpeggios, chords. Something. Not necessarily a lot, if you are practicing only for a half an hour, maybe spend on five minutes on those exercises, and then start to learn the repertoire. And it depends upon how many pieces. If you have only a half an hour, I would study only one piece. Practice only one piece. And it depends on if you’re just beginning to learn that piece, then you need of course to play right hand alone, and then left hand a lone, then pedals alone, and then work on all the things in combinations. V: I would just add, Ausra, that Henry needs to look at what pieces are the most difficult for him and work on them first. A: Sure, and you know if you have a longer interval to practice, let’s say an hour or two hours, then try to do technical exercises first for a little bit longer, and then work on the piece is the hardest on your repertoire list. And then, things that you have already learned and maybe just need to refresh or re-polish, or to repeat, then practice them later on. V: And it’s okay sometimes, not to play the entire repertoire in one session. A: Sure! Don’t try to put everything in that session, especially if that session isn’t long. V: So if you’re playing 30 minutes of repertoire and you are only practicing for 30 minutes, obviously you are not able to play even once, the entire collection of your repertoire, because you are playing slower than in concert. A: So, and you know, I would say if you are planning your next practice session, you have to know what your main goal will be—what you will want to achieve. V: This is called deliberate practice, and we all know that it takes 10,000 hours to achieve mastery in any advanced field, and especially in such an advanced field as organ playing. But you have to practice deliberately. Not just playing for the sake of playing, but knowing your goal and trying to improve with each repetition. A: Sure, you know your piece and know the hardest parts, and maybe on your next session, you will know that, let’s say you have 5 hard spots in the piece, then you will tell yourself, “Next time I will do the first two hard spots of that piece.” And then practice them diligently. V: So guys, we hope this was helpful to you. Please send of more of your questions, we love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice, A: Miracles happen.

This blog/podcast is supported by Total Organist - the most comprehensive organ training program online. It has hundreds of courses, coaching and practice materials for every area of organ playing, thousands of instructional videos and PDF's. You will NOT find more value anywhere else online...

Total Organist helps you to master any piece, perfect your technique, develop your sight-reading skills, and improvise or compose your own music and much much more... Sign up and begin your training today. And of course, you will get the 1st month free too. You can cancel anytime. Join 80+ other Total Organist students here Are you struggling in playing pedal scales? I know those heels and toes in alternations might be confusing. And sometimes people in my Pedal Virtuoso Master Course need a little visualization. So here's a video I made on how to play the D major scale with your feet over one octave which I hope you will find useful..

Some of you may have seen my video on playing the C major with pedals. What is missing in this demonstration is the reasoning for choosing this kind of technique and pedaling. I'll try to explain them today.

The basic principle (left toe, right toe, left heel, right heel, keeping the heels and knees together) used in playing scales comes from the French legato organ school which was basically invented by the Belgian organist Jacques-Nicolas Lemmens in the middle of the 19th century. However, unlike with manual scales where there is a certain uniformity in fingering, pedaling was never uniform. The main principles are there but certain authors (Dupre, Gleason, Davis, Ritchie/Stauffer and others) can differ slightly from one another with their scale pedalings. In this video I play 5 pitches (C, D, E, F and G) with the left foot only because some people would feel it very awkward to play with the right foot on the D and F. Other authors might be a little more strict with their approach. Of course, if we would be dealing with early organ technique, then the proper way to play the scale would be with alternate toe pedaling - left, right, left, right etc. Importantly, there is no foot crossing here - you have to move both feet together as a unit. Two feet are like two fingers of an extra hand in early music (and to a certain extent for the Romantic music, too). [Thanks to Andreas for inspiration] A few of the people wanted to have a visual demonstration of the scale exercise I described yesterday. In order to make practice more clear to people, I decided to create a score with examples of this kind of exercise (image files: Page 1, Page 2, Page 3).

In places where passages in two octaves should go over the range of the pedalboard (A minor and G major) there could be other options available with a few extra notes here and there but this version works quite well, too. I hope you can take advantage of this exercise which will boost your hand and feet coordination significantly. Practice this set of exercises today on the organ with 2 manuals and pedals:

1. Scale in C major (2 minutes): Right hand ascending eighth-notes Left hand descending eighth-notes Pedals ascending quarter-notes 2. Scale in A minor (2 minutes): Right hand ascending eighth-notes Left hand ascending quarter-notes Pedals descending eighth-notes 3. Scale in G major (2 minutes): Right hand descending eighth-notes Left hand ascending eighth-notes Pedals ascending quarter-notes 4. Scale in E minor (2 minutes): Right hand descending eighth-notes Left hand ascending quarter-notes Pedals ascending eighth-notes 5. Scale in F major (2 minutes): Right hand ascending quarter-notes Left hand ascending eighth-notes Pedals descending eighth-notes 6. Scale in D minor (2 minutes): Right hand ascending quarter-notes Left hand descending eighth-notes Pedals ascending eighth-notes NOTE: All parts must finish together at the starting point. Count all repetitions and post sum to comments. If you practice pedal scales and arpeggios regularly, you know that with time it will help you develop a perfect pedal technique. The problem with such training is that there is a temptation to rush through many scales a day, to do many exercises but not necessarily perfecting them all.

Sometimes we do that because we feel we need to attempt to do everything at once. But in reality, when we play too many things, too many exercises, too many pieces in one practice session, we don't accomplish anything substantial. If we play through 24 different scales and arpeggios a day just once, it takes considerable amount of time but the progress is very small, if any. This is because in every scale we might make a mistake or two. The wisest thing would be to correct that mistake but sometimes it's difficult to force oneself to stop and perfect that pedal scale or arpeggio. But there is no other way - we have to perfect what we do, if we want to accomplish something remarkable. So it's better to play only 2 or 4 scales a day but aim for perfection instead of rushing through all of them at once. Of course, once you master all the pedal scales and arpeggios and want to keep up your already polished technique, then playing through them only once is sufficient. But that's after the real hard work is done, after you master scales in 24 different keys in one octave, two octaves, tonic arpeggios, dominant seventh chord arpeggios, diminished seventh chord arpeggios, scales with double pedals, chromatic scales and so on. By the way, do you want to learn my special powerful techniques which help me to master any piece of organ music up to 10 times faster? If so, download my video Organ Practice Guide. Imagine you sit on the organ bench and want to play a pedal solo line with the hand part silent. This could be an excerpt from an actual organ piece, such as Toccata, Adagio and Fugue in C major, BWV 564 by Bach, or a composition for pedal solo, like Epilogue from Hommage a Frescobaldi by Langlais. It could even be a pedal scale or arpeggio.

The question is this: where do you keep your hands in such situation? There are 3 primary ways to do this correctly which are taught in organ method books. 1. On the organ bench 2. On the sides of the lower keyboard 3. On your knees With the first method, you play the pedals while holding onto the organ bench. Here you are sort of helping with your hands to keep the balance of your body. This way makes it even easier to pivot to the new pedal position because your hands may involuntarily help to push to the right or left when needed. The problem with this method is that your hands may not always be free to help you do that when you play the organ. In fact, very often your hands will be busy playing manual parts of your organ compositions. Another way is to keep your hands on the sides of the lower keyboard. As with the previous method, the hands are a big help for keeping balance. However, the inherent danger here is to press the bottom or the top notes with your palms by accident (I've personally seen this happen) which can make a lot of noise especially if you are using a loud registration. The third way is just to rest your hands on your knees. Although this method takes perhaps a couple of weeks to get used to but then you are quite sure that you are playing with your feet WITHOUT the help of the hands at all. You should use other techniques for changing position. This is my personal preferred method of playing pedals. By the way, if you want to perfect your pedal technique, check out my Pedal Virtuoso Master Course - a 12 week training program designed to help you develop an unbeatable pedal technique while working only 15 minutes a day practicing pedal scales and arpeggios in all keys. When it comes to building your organ technique, playing scales, arpeggios, and chords is one of the legitimate ways to achieve that. However, some organists believe there are better techniques in developing one's finger independence and dexterity. In this article, I will share with you my opinion on this subject.

Let me start by saying that scales provide the benefit of finger dexterity. There is no question about that. In fact, that's the very reason why scale practice was invented in the first place. However, my experience in organ teaching and performance tells me that there are other technical exercises and etudes that are even more beneficial than simple scales. If you want to reap more benefits, practice not simple scales, but scales in double thirds and double sixths (if your technique allows). As with all things, slow practice is the best. Fast tempo will be achieved naturally once you are ready. Take C major and A minor scale and practice them by playing thirds in each hand. Next week take another pair of keys progressing in ascending order of accidentals (1 sharp, 1 flat, 2 sharps, 2 flats etc.). Try to play each scale correctly at least 3 times in a row. Double thirds (and double sixths) are an integral part of any advanced organ music, so if you are serious about your organ practice, you should practice such scales repeatedly and regularly. If you haven't done this kind of practice before, at first it will be quite a challenge just to play with correct fingerings even in a really slow tempo. Do not expect the results overnight. But if you continue to practice this way, your finger independence and technique will skyrocket. A word of caution: since this is an advanced technique, be careful of not to overextend yourself to avoid any damage to your fingers and hands. Always be conscious of how you feel. Some minimal tension is fine, but as soon as your fingers and hands feel tired, take some time to rest and shake off the excess tension. Scales are also good for giving the benefit of knowledge of circle of fifths, all keys and some music theory issues. So we can't really completely dismiss playing scales. But if you specifically want to improve your finger technique, try scales in double thirds (with correct fingering, of course). On the other hand, pedal scales and arpeggios are wonderful in developing the flexibility of an ankle which is the key to the perfect pedal technique. As with manual scales, take 2 keys per week and master them. Use the above tips when you practice scales on the manuals or on the pedals. They will help you to perfect your organ playing skills. By the way, do you want to learn my special techniques which help me to master any piece of organ music up to 10 times faster? If so, download my FREE video guide "How to Master Any Organ Composition": http://www.organduo.lt/organ-tutorial.html Or if you really want to develop unbeatable sight-reading skills, check out my systematic Organ Sight-Reading Master Course: http://www.organduo.lt/coaching.html Have you ever observed the pedal technique of a world-class organist? It

seems like he or she can play effortlessly for hours at a top speed. How do you develop speed in your pedal technique? In this article, I will share with you 4 tips which will help you to achieve this level of proficiency. 1) Play scales for the pedals. The single most important exercise that the legendary French organist Marcel Dupre used when he was unable to play the manuals due to his wrist injury was pedals scales. Practicing pedal scales on the organ in all major and minor keys will develop flexibility of an ankle which is the secret to a perfect pedal technique. 2) Play arpeggios for the pedals. If you want even more benefit you can go one step further. Take 1 new major and minor key a week and play arpeggios on a tonic chord. You can also practice arpeggios on a dominant seventh chord and a diminished seventh chord which is built on a 7th scale degree (or raised 7th scale degree in minor). 3) Practice slowly to achieve speed. Although it sounds counterintuitive, it is best to take a slow practice tempo in which you can avoid mistakes and play fluently. Then little by little you can raise the tempo until you reach your desired speed. However, be careful not to force yourself to play faster because it has to be a natural process. You will play faster when you are ready for it. 4) Correct your mistakes. If you make a mistake in pressing the wrong note or playing the notes in uneven rhythms, always go back, slow down and play correctly at least 3 times in a row. This way you will form correct practicing habits. Note that if you are a beginner at the organ, it is better to postpone practicing pedal scales and arpeggios for a later date. Instead, take up some easier exercises for alternate toes first. Use the above exercises and tips and start perfecting your pedal technique today. To achieve such level when you can play the pedals fast and effortlessly may take many months of practice but I can assure you that you will start seeing some tremendous changes in your pedal playing very soon. By the way, do you want to learn to play the King of Instruments - the pipe organ? If so, download my FREE video guide How to Master Any Organ Composition in which I will show you my EXACT steps, techniques, and methods that I use to practice, learn and master any piece of organ music. |

DON'T MISS A THING! FREE UPDATES BY EMAIL.Thank you!You have successfully joined our subscriber list.  Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas

Authors

Drs. Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene Organists of Vilnius University , creators of Secrets of Organ Playing. Our Hauptwerk Setup:

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

This site participates in the Amazon, Thomann and other affiliate programs, the proceeds of which keep it free for anyone to read.

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed