|

Vidas: Hello and welcome to Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast!

Ausra: This is a show dedicated to helping you become a better organist. V: We’re your hosts Vidas Pinkevicius... A: ...and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene. V: We have over 25 years of experience of playing the organ A: ...and we’ve been teaching thousands of organists online from 89 countries since 2011. V: So now let’s jump in and get started with the podcast for today. A: We hope you’ll enjoy it! V: Let’s start episode 588 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Amir. He’s taking our Organ Sight-Reading Master Course. And when I asked him how his organ playing is going so far, he writes: “It was not that bad, my main difficulty are the unexpected changes in rhythms and jumping notes.” V: Hmm. I think this is a fairly common challenge. Right Ausra? A: Yes. V: Why is that? A: Because people don’t like to count. V: That’s what I suggested to him. Count out loud. When you’re playing, of course, it’s better to play really, really slowly, maybe half as fast—maybe at the 50% of concert tempo, or even 40% or 30% if you need. But more than that, you need to count out load. If you have a 4/4 meter, the best way for me to count out loud is simply divide the beats into 8th notes. “1-and-2-and-3-and-4-and.” Would that help, Ausra? A: Yes, I think it would be very helpful. Right now, I’m working on recording Buxtehude’s Chorale Preludes, and even after having the experience of playing music for...I don’t know for what… but really many years, because I started when I was five, I still have trouble sometimes if I don’t count, because what Buxtehude does, he likes to change the rhythmic formula very abruptly, suddenly and unexpectedly. And if you were not counting before, you might get in real trouble, because you sort of lose the sense of the rhythmical flow. V: Yes. I think the first one that you recorded, Chorale Prelude by Buxtehude, “Ach, Herr mich armen Sünder” I think. It has very intricate ornamented Chorale melody in the right hand. A: Well, and not only this one; I guess he likes to do it in most of his Chorale Preludes. Very few of them are even, but most of them are very varied. V: For me, what I last recorded, Brahms’s Chorale Prelude, “Mein Jesu der du mich” from Opus 122, this is number 1. And the rhythms are okay. They’re not… A: Yes, I think Brahms is pretty much very even in rhythms—at lease in these Chorale Preludes. V: Yes, unless you’re playing one of those Fugues, where you have to change between duplets and tuplets and triplets. A: Yes, that’s a different story. But now we are talking about Chorale Preludes. V: So I didn’t need to count a lot. At this stage of my career, it comes naturally most of the time, but sometimes I do need to double check. A: Well, I’m not counting Buxtehude out loud, but I do it in my head. V: But consciously, right? Doing it. A: Yes. Definitely. V: If the tempo is really slow, sometimes you need to subdivide it even more up to 16th notes. A: Yes, that’s what I did when I learned the *** Icarus. I subdivided into 16th notes. V: Instead of saying “one-and-two-and” you would say “one-ee-and-uh-two-ee-and-uh-three-ee-and-uh-four-ee-and-uh.” It’s like a tongue twister! What would it be in 32nds? People have asked me that, but I forget. A: Better not go there! V: If you need to subdivide in 32nds, this means you’re playing music that is too difficult, basically. Right? If you still need to do this. I think 16th notes are the limit for me at least. I wouldn’t subdivide into 32nds. A: Probably not. V: Right. So that would be helpful, of course, to Amir and others who are struggling with unexpected changes in rhythms. A: What about jumping notes? I am not exactly getting what he means by this question. Is it difficult for him to hit the right note after a big leap or what? Or to follow the score if it’s a jumping melody? V: Maybe both! Yeah, if you have leaps more than a fifth, yes, you can easily reach a note by a fifth because you have five fingers and an interval of a fifth requires 5 adjacent keys. But if you have a sixth or seventh or an octave or even above an octave, you have to switch position. How do you do that, Ausra? How do you adapt? Or do you not do it? A: Well, you know, if it’s Baroque music, then it’s very easy. You just have to articulate. You have articulate each note, and it shouldn’t be a problem, because you don’t have to stretch your arm to reach it to play legato. V: You move the entire wrist! A: Yes! V: But try not to do upward motion with your hand. Slide to the right or to the left. A: Yes, you need always to keep the contact with the keyboard. V: Touching! A: Touching it, yes, or almost touching it. V: You know, there was an account about Johann Sebastian Bach playing organ, and people have observed him, that he almost doesn’t depress the keys. The organ plays itself, basically, it seems, in his case. Right? Do you, can you elaborate a little about that? A: That’s a true mastery, you know, you have to be really economic about… V: Efficient… A: ...efficient about using your motions. It helps to play in a fast tempo, I would say, and to avoid mistakes. V: It doesn’t feel like work, then. It feels like a natural flow. Remember, we have observed a great Chinese cook back in the States when we were observing him prepare our steamed vegetables, I think, how he moves with his pan and with his vegetables and chopping knife, everything was so efficient, fast and barely noticeable. This is true mastery, right? A: Yes, it is. It’s interesting that you decided to compare Bach and a Chinese chef! V: Well, I mean if you do the same motion over and over again like a thousand or ten thousand times, you get really, really efficient! Right? You peel like an onion those layers of inefficiency. A: Yes, or you would get over use syndrome in your wrist for example. V: Yes, if you do it with tension! If you don’t relax muscles after using them, right way. Alright? So, Amir, with jumping notes, try to use this sliding motion with your wrists and then you will be fine! So guys, we hope this was useful to you. Please send us more of your questions; we love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice, A: Miracles happen. V: This podcast is supported by Total Organist - the most comprehensive organ training program online. A: It has hundreds of courses, coaching and practice materials for every area of organ playing, thousands of instructional videos and PDF's. You will NOT find more value anywhere else online... V: Total Organist helps you to master any piece, perfect your technique, develop your sight-reading skills, and improvise or compose your own music and much much more… A: Sign up and begin your training today at organduo.lt and click on Total Organist. And of course, you will get the 1st month free too. You can cancel anytime. V: If you like our organ music, you can also support us on Patreon and get free CD’s. A: Find out more at patreon.com/secretsoforganplaying

Comments

SOPP579: Definitely counting while reading new music is helping me to keep on a stable rhythm4/4/2020

Vidas: Hi guys! This is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 579 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Amir. And he writes: Hi Vidas, Definitely counting while reading new music is helping me to keep on a stable rhythm. I still found rapid shifts in note values and spacing of melodies in my left hand a bit challenging. Thanks. V: Ausra, what does he mean about “spacing of melodies” in his left hand? A: I guess he has trouble in his left hand in general... V: Mm hm. A: ...it seems to me. Well, because he is keeping talking about playing music in a stable rhythm. What I would suggest for him to do, since he has trouble with the left hand, that he would not sight read music with both hands together. V: Go back to single lines. A: That’s right. V: Mm hm. He is working on my Organ Sight Reading Master Course, and I’m not sure which week he is on, but from the beginning, and quite a few weeks involves only one single line. A: I see. V: Soprano, then alto, then tenor and bass. A: But I guess he’s talking about when he plays both hands together. V: Mm hm. A: Or if it’s the Sight Reading course, then maybe he just needs to take a slower tempo. V: Yes. I think his question was aimed for this course, this particular course. And ideally, a person should take a very slow tempo and just play it through, one day. And the next day will be the next exercise. Not to master completely, one exercise, but just to sight read it. It could be done twice actually. One, and the second time through also works. But for him, I think sometimes the tempo is too fast. You know, when I say play it slowly, people are just saying to what they think is slow. And for some people, I think, or for most people, slow is not slow enough. A: Yes. Do you think it’s really important to keep steady tempo when you sight read things, or you may slow down when things get harder? V: I would prefer to keep a steady tempo. Even though it’s really slow. I would take it twice as slow - even more than twice as slow. You know, if you take a really slow tempo and it’s still unsteady and uneven rhythm, and it’s still too difficult for you to play without mistakes, it means that either the texture is too complicated for you, or the tempo is too fast. So you can slow down, right, but you cannot omit one line from a single line; already, it’s already too few notes. So in general, might be just a good idea to slow down. A: Yes, I think that’s a good suggestion. V: Yes. You guys, may be noticing a change in our audio quality, and we’re just testing the first recording we’re making on our new MacBook Pro, using Garage Band app, and I’m not sure how it will go, but so far we’re just testing it. Let us know if the quality is different or better, or whatever you feel, whatever you hear. Okay? So, and keep practicing of course, and sight reading. Sight reading from my Organ Sight Reading Master Course is really helpful, because we start with one single line, then going to two parts, three parts, and finally four parts, of Bach’s Art of Fugue. But then, in Bonus Content, we have seven weeks, seven additional weeks. We have Reger’s small chorale preludes. So basically, the entire course is baroque-like course with articulation, but the bonus material is dedicated for legato playing as well, because people were asking about modern technique as well, modern touch. Okay, and let us know how your practice goes, and keep sending more of your questions. We love helping you grow. V: This was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: And remember, when you practice, A: Miracles happen. SOPP419: I could never play a triplet with one hand and four 16th notes with the other hand together3/30/2019

Vidas: Hi, guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 419, of Secrets Of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by May, and she writes: Hi Vidas, Thank you for sending me the week 6 Harmony material. I have been working hard (and struggling) with the chords, the progressions and the sequences in the past 2 weeks. I find it most difficult to play with hands only using 2 right hand fingers and 2 left hand fingers. It is easier to play with left hand doing the bass only and right hand playing the triad (chords in closed positions). Playing the bass with the pedal is also much manageable than playing with 2 fingers from each hand. It takes a long time to go through the exercises first with hands only and then with pedals together. Shall I practice with hands only, with hands and pedals, or both? What do you suggest? I am working on the sight reading master course at the same time. I struggle with the rhythms in week 3 day 2's triplets. I could never play a triplet with one hand and four 16th notes with the other hand together. If I assign 12 units to each quarter note, each note of a triplet will get 4 units and each 16th note will get 3 units. I am not sure if it will help me to get a better sense of this complicated rhythm by doing this. It will also take a long time to finish the passage. Do you have any suggestions? Thanks, May V: So this is sort of two fold question; one is about harmony and another is about playing complex rhythms. A: Yes. And I know what she talks about, how uncomfortable is it to have two voice in one hand and two in another, but that’s the way the voice leading works because you cannot always use only a closed position. And if you need to play in an open position then you really need to play something with your left hand too. If you don’t like to play two voices with your left hand, then play bass with the pedal, tenor with your left hand and two voices with your right hand. V: Mmm-hmm. A: It will not make life easier. Because I think that trouble is the tenor voice. V: Mmm-hmm. Yeah, I… A: It always is the tenor voice. V: Mmm-hmm. I could suggest here two things: one is to sight-read more hymns with or without the pedal, doing the same thing that you are talking about—two and two–left hand takes two voices and right hand takes two voices, or right hand takes voices, left hand takes one voice, and the pedals take one voice. Those versions are very beneficial. So, she practices harmony, but at the same time, sight-reading hymns would really be beneficial to her because it’s the same disposition of voice. A: Well, yes, but by these two questions by May, I see actually the connection. It’s all what she talks about is connected to this coordination problem. V: Mmm-hmm. A: Which is very common in us, all, I think. Because if you cannot manage triplets in one hand and then sixteenths with your other hand it also means coordination, and basically independence of your hands. V: One part of your brain must think in triplets and another in sixteenth notes. A: That’s right. I remember when I first encountered this problem; it was in Franck’s A Major Fantasy. It has a couple [of] spots where you have triplets, and… V: What kind of fantasy? A: In A Major. V: A. Mmm-hmm. A: Yes. A Major. V: And I’ve seen this rhythms in Messiaen’s music, uh… A: Well I saw many times these rhythms. This was just the first time when I encountered it myself. V: For example in Messiaen’s L’Ascension, the second movement. A: What would you suggest? How to practice it? V: First of all, hands separately. Not necessarily the entire piece but maybe a short fragment of 2-4 measures. And each hand has to know this part completely, like inside out. I’ve done this repeatedly, ten, twenty, a hundred times, with each hand. And suddenly, when put those hands together, they click and play separately, like two different people. Because they, your hands basically remember the muscle memory. A: That’s a very good suggestion. And I had that trouble sometimes even playing trills. And I don’t think it was because of poor technical skills or something. I think it was also psychological problem too. Because when I know that spot, tricky spot comes, I would get tense. I would get like muscle spasms and then I would fell. But... V: You mean fall. A: Fall, yes. V: Mmm-hmm. A: And I would fall. And what helped me actually, relaxation and breathing. V: Another method would be to think about sixteenths as just twice as smaller units of duplets. You know, three against two is easier to play than three against four. A: Well, but for beginners, three against two is also a big challenge. V: But you could... A: But of course… V: Mathematically… A: Yes. V: count it... A: Yes. V: Those rhythms. A: You can everything count mathematically. That’s what math is for—that you could calculate anything. V: So, the first and the third note of the sixteen group, would fit nicely with the triplets. But the second and the fourth need to be inserted somewhere in the middle, right? So... A: But you still have to know that spot where it has to be… V: Mmm-mmm. A: Put in. V: But if you make a focus on the first and the third group notes, then two and four maybe take care, by themselves. No? A: (Laughs.) I wish it would be like this. V: Okay. And one last suggestion is about strengthening her left hand a little bit more. I have two courses concerning this. The first is left hand training, which is based on six trio sonatas by Bach, where the player is required to practice any part that organist play from trio sonatas—right hand, left hand, or the pedals—but only with left hand. And in various keys. I transpose them, in multiple keys. It’s just for strengthening the left hand. That would be beneficial for May. And then the second level is two part training where you take, where I take the same trio sonatas, but people need to practice two parts at a time—left hand, for example and pedals. A: Yes, I believe it might be very helpful. V: Mmm-hmm. And that might help her with harmony disposition when she has to play pedals in the feet, tenor in the left hand, and two voices in the right hand. Right hand is easier so left hand and pedal need to be strengthened—this coordination. A: True. V: Okay. So anybody who struggles with this could really benefit from those two courses I think. Alright guys. We hope was useful to you. This was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: And remember; when you practice... A: Miracles happen! DON'T MISS A THING! FREE UPDATES BY EMAIL.Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start Episode 216 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. And this question was sent by Denham and he writes: Please can you do a masterclass on the In Dulci Jubilo in the same Orgelbuchlein Book. BWV 608. How to master the rhythm of 3 against 2s. It is so difficult. Thank you Vidas! V: Do you remember this piece (here is slow motion video), where it’s a canon between the chorale parts, I think, the soprano part and the pedal part, but then hands are playing interchangeably duplets and triplets. Remember, George Ritchie talked about that. A: Yes. V: In our early music performance class that’s one of the more difficult things to learn, I think, right? A: Yes, especially for the beginners. V: So. But, actually, it’s not very, very complicated when you think about it. It’s not like three against four. A: Oh, that’s true. Three against four is much harder. Or you know, if you think three against two is hard, pick up the big cycle of organ music by Petr Eben called “Laudes,” and you will find rhythmic figures that would curl your tail! V: Mhm, interesting. You see, “In Dulci Jubilo” is written in A major, and in original notation, it has 3/2 meter, and, against a half note, there are triplets of eighth notes. But of course, in the modernized version it’s a little bit different because we need, then, to have probably a different type of notation, right? A: Mhm, yes. V: We need probably to have something like quarter notes against dotted half notes or eighth notes against dotted quarter notes. Right? A: That’s true, but it’s again the same problem: three against two. V: Mhm. A: But, you know, I think for people for whom it’s so hard to play triplets, vs. duplets, it’s probably because they don’t have a well enough developed hand independence. Don’t you think so? V: Yes, of course you’re right. And this can be achieved by playing and counting those parts separately, right? I’m not sure if Denham does this, playing parts separately. But in this piece, there are actually four parts in this canon between the soprano and the bass. And the bass, of course, has to be played, probably, with the 4’ stop, which will sound an octave higher. And you see sometimes, like in measure 3, there are three groups of triplets in the tenor voice, and six notes in the alto playing duplets. That’s what’s the most difficult, is to play alto against tenor---inner voices, right? And sometimes they switch, three against two, or two against three. A: Yes, but you know, first of all you would need to work in combination. Sometimes it sounds boring, I know, and probably our listeners are getting bored of my advice of working in combinations, but this is really what will help in a piece like this, because if you would, let’s say, play only right hand and pedal, first, and then left hand and pedal first, and after a while you would be really comfortable with it, only after long with those combinations, you can try to play that third measure. V: Or the fourth measure when they switch. A: Or the fourth measure. Yes. V: Mhm. A: But anyway, you know, if after working in combinations for let’s say two weeks, you still have struggling playing duplets against triplets, then maybe you just need to do simple exercise, not playing, but trying to… V: Clap? A: ...clap them, but yes, not with both hands, but… let’s say... V: Tapping! A: Yes, tapping. Imagine that you play on your hip... V: Mhm. A: ...one left and right. I don’t know… do the duplets with your left hand, and triplets with your right hand. Do them separately and then put everything together. And then you will be comfortable with your left hand clapping duplets and your right hand clapping triplets, then just switch... V: Mhm. A: ...and do triplets with your left hand, and duplets with your right hand. V: Hm. That’s possible. And the way to learn this is actually very simple. You can imagine, those two voices. When they are mixed they form a rhythm in em… let’s say 9/8 meter. Instead of playing with both hands, you can play with one hand. <claps the rhythm x_xxx_x_xxx> this way. And when you need both hands, it’s the same thing. So basically, I’m tapping on my computers for you to hear better. <taps out the rhythm x_xxx_x_xxx_x_xxx_>. Right? I can switch, too <taps out the rhythm again x_xxx_x_xxx_x_xxx..>. So basically, you have to fit the quarter note---the duplet---in the middle between the second and the third of the triplets. Right Ausra? A: That’s true, yes. V: Mhm, and you do that by playing separately, or tapping separately, first. A: Yes, but, you know, this is the struggle that each beginner has to overcome. It seems so hard as a beginner. But after a while, you know, after ten years, you will be just laughing about things like this. V: Mhm A: Because by that time you will encounter much, much, much, more difficult rhythmic problems in organ music. V: And of course, in Bach, this is more complex stuff. He was one of the pioneers of course to do this---two against three---and it was quite unusual. And that’s why he used an old rhythmical version writing in 3/2 meter but writing triplets basically in eighth notes. A: Yes, but if you would think about, like, later composers, let’s say, I remember playing Céasar Franck, and in his C major Fantaisie, he used fourths against triplets. V: Mhm. A: So four against three, and it was hard for me, because I was also maybe like on my second or third year of organ playing at that time. So, but then think about Messiaen, how complex his rhythms are. There, you have to subdivide in 32nds maybe, you know, in order to get the rhythm right. Or you know, like I mentioned Petr Eben before that. So… V: I’m just looking at the Google Brahms piano exercises. If you want more advanced exercises, especially for more advanced rhythmical figures, try to study 51 exercises by Brahms. That’s an amazing place. And, even the firs exercises is just absolutely impossible to play right away. You have to spend some time with it. Maybe a few days to get it. Even the first exercise. So, Brahms was a champion to do this, because in the Romantic era, they had all kinds of rhythmical variations, right? So you will also need to do this. So, we hope this was useful to you. And study Brahms and other things, too. And remember to send more of your questions. We love helping you grow. This was Vidas! A: And Ausra. V: And remember, when you practice, A: Miracles happen. Yesterday while I waited for the students of Unda Maris organ studio to gather, I had some time in the church and decided to record 4 of my improvisations. I hope you'll enjoy them:

1. Wind 2. Snow 3. Fire 4. Lizard Basilisk If you like them and would not want to miss anything we post in the future, feel free to follow to our new channel on Musicoin, a platform which treats musicians fairly. And now let's go on the podcast for today. Vidas: Let’s start Episode 113 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. You can listen to the audio version here. Today’s question was sent by Martin. He writes: I really enjoy your podcasts and postings. I have a question for you. Presently I have a new student (8th grade) who indicated an interest in playing the organ. He has a piano background, and when I asked him to show me some of the materials he is currently studying with another teacher on the piano, it appeared to be significantly less advanced than some of the pieces he played for me by memory. I gave him one selection to prepare for me with minimal pedal and asked him to prepare only the parts he would play on the manual. When I listened to it this week, there were practically no difference in eighth notes and quarter notes. He told me that he that he felt he was a very poor sight-reader and learned by ear and by writing in the note names. I'm wondering if he has actually learned to make a connection between what is written on the page and what he plays. I feel badly because he actually plays quite musically from memory, but it has to take him an inordinate amount of time. I asked his parents, and they feel his reading level in other material is good. I assigned a c major scale and arpeggio in separate hands for next week and told him that we would start with some basic sight reading in that key for next week (treble clef only). This would include clapping of basic rhythms and then transferring to the keyboard. Does this sound like a reasonable approach to lay the foundation for actual music reading? If you don't answer this, it is fine. I know you are both quite busy. Martin So Ausra, this situation is quite depressing for this teacher, right? Ausra: Yes, it might be very hard to have a student like this. And I guess that probably his student got his early musical training based maybe on the Suzuki method. I’m guessing so; I’m not 100% sure, but that’s my best guess. Vidas: Mhm. Ausra: Because the Suzuki method is based on learning how to play by ear, actually; you don’t read a music score… Vidas: Until later. Ausra: Until later. Until, actually, much later. And this method was developed in Japan by a violinist--you know, Suzuki. And it works for violin fairly well, because they have only 1 line. And I have heard violinists after many years, who were trained as Suzuki players when they were very small; and the advantage of this system was that you can start to play music very early, in that case. And they start teaching you when you are at the age of like 3 years old--which would be probably impossible, if you wanted to make your student sight-read music at that early age, from a music score. Vidas: Mhm. Yeah. Ausra: But what I also have heard--and that’s a disadvantage of this system--is that although they develop perfect pitch by playing by ear all the time, they actually never learn to read music very well. Vidas: Mhm. Ausra: And they always struggle with that, even later on when they are adults. So, what do you, Vidas, think about this problem? Vidas: First of all, about the Suzuki method: yes, Shinichi Suzuki developed this system in hope of helping children to learn like they would be learning their mother tongue. Because when they learn to speak their native tongue, they don’t learn to read first, right? They want to imitate first what their parents say--separate words, phrases. So the small kids also watch their peers and brothers and sisters play, let’s say, violin, or other instruments; observe them for a month, or two or three, or even half a year; until they are so motivated to pick up an instrument themselves and try it out, by ear without ever looking at a score. But as Ausra says, it’s a great system for developing perfect pitch; but if you’re not very very hard working, then reading music is a problem later on. Only those extremely hardworking students can be proficient in reading music as well, using this Suzuki system. So if Hubertus has a student in 8th grade--who knows if he was trained in Suzuki or not, but--apparently, he is a poor sightreader. Ausra: Yes, and I remember when you know, way back, many years back, I was working at one school, and teaching first and second and third graders piano. I also noticed that for some students, it’s much easier to look at my fingers when I’m playing, and then to mechanically memorize what keys I’m pressing--and not look at the score. That was also one of the cases I had. This was also frustrating, actually, because I think that reading music from the score should come first. Of course, the progress then will be slower, probably, than learning other methods; but it will be definite, and finally it will lead you to more success. Vidas: Especially if you are an 8th grader. Ausra: Yes. So I would suggest, for Martin with this particular student, don’t let him play like this, not using the score. He must look at the score all the time until he will be able to play it correctly, with right rhythms (not to play like he says, eighth notes like quarter notes)... Vidas: Mhm. Ausra: And only then, after he is comfortable enough while playing from the music score, let him play from memory or by ear. Vidas: I have a proposition for Martin. It will be a little bit of extra work for the student, but in the end it will be much more beneficial. What about assigning sight-reading exercises or short pieces for your student at home, and asking him to record his playing and send the mp3 recordings to you--to the teacher? It would be like extra care and extra support from you. You don’t have to create them, but you just have to know that he has prepared something new for him. And he cannot really avoid playing from the sheet music this way--let’s say one page per day, or something. A short piece; maybe just one single line, LH, RH alone. What do you think about that, Ausra? Ausra: Yes, I think that would be very beneficial. Vidas: Because a student will not be willing to do this on his own, obviously, because it’s difficult and he has to force himself. So that would be like an additional level of support from the teacher. And also, when he comes to you on a weekly basis, to the lesson, how about spending the majority of the lesson time on sight-reading? Ausra: I think at the beginning it would be great. Because that’s what he needs in order to be a better player, a better musician. Vidas: Yes. So, assign him a collection of music; maybe...I don’t know, whatever you like at that level, and assign one page per day of something or one piece per day, and see if he can focus on recording his assignments and sending the mp3s to you. Ausra: Yes. And I don’t think he will be very happy at the beginning with this new assignment; but you know, looking into the future, I think he will be thankful to you. Vidas: True. And guys, if you yourselves struggle with sight-reading at the level that you miss quarter notes and mix them with eighth notes and they all sound the same and you feel the need to write down the note names above or below the notes, then you can do the same thing. Force yourself to record, and it will be like an accountability system for you. Ausra: That’s what some of my students do, in solfège with exercises in C clefs, where we have to play one voice on the piano and to sing another voice; and we have like 2 different C clefs, like for example, tenor and alto, or tenor and soprano; so they just write in the note names! And it just makes me furious! Vidas: Yes. It’s not clef reading at all. Ausra: Yes, it’s cheating, actually! Vidas: It defeats the purpose. Okay, so don’t cheat, guys. I think you want to succeed in this for the long-term. And remember that the first few weeks will feel like hell, but later on will be purgatory, right? Ausra: Yes, and then… Vidas: And then later, heaven! Ausra: Yes, that’s right! Vidas: And on this optimistic note, we leave you to your practice. Because when you practice… Ausra: Miracles happen. By Vidas Pinkevicius (get free updates of new posts here)

The other day I was preparing for my today's recital of organ improvisations on the medieval Anglo-Saxon heroic poem "Beowulf" where lots of fighting with a monster giant Grendel, his mother, and the dragon take place. Obviously in this story one of the main companions of the hero is a horse. How do you depict a galloping horse or riders with musical means? It works exceedingly well with dotted rhythms. For example, playing fast-paced repeated chords in the rhythm of dotted eighth-note and a sixteenth-note. Something like this. Try it. It's fun. By Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene (get free updates of new posts here)

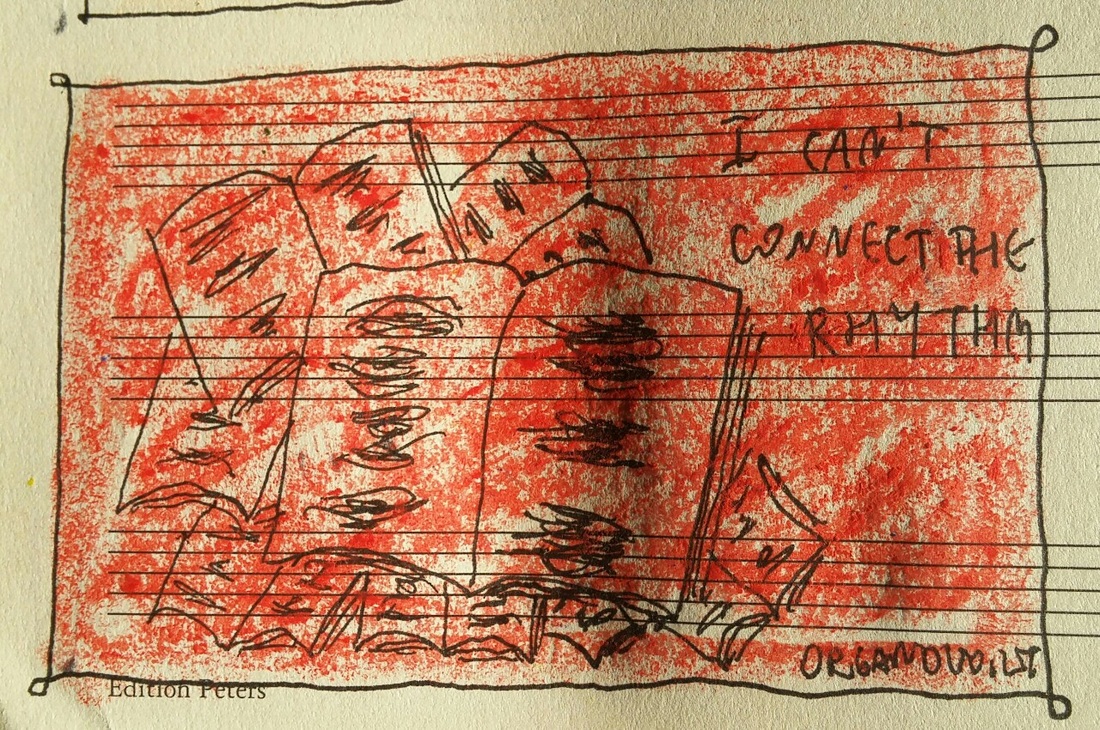

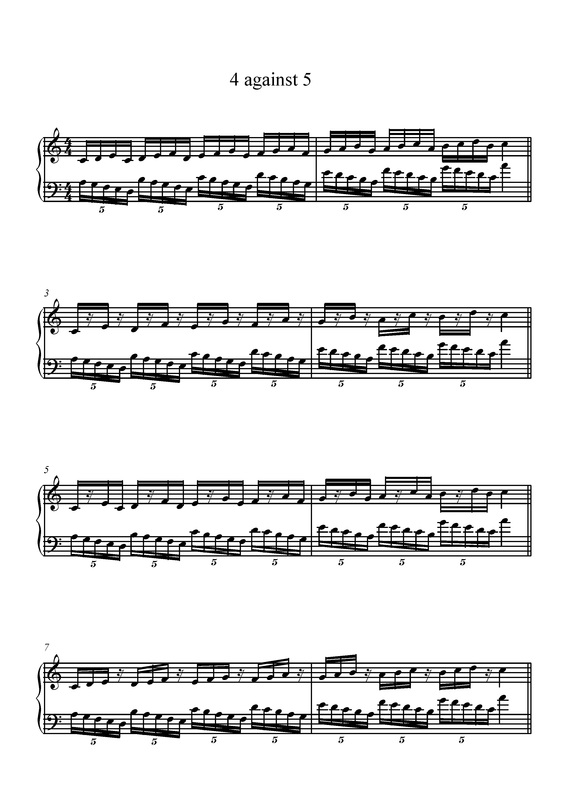

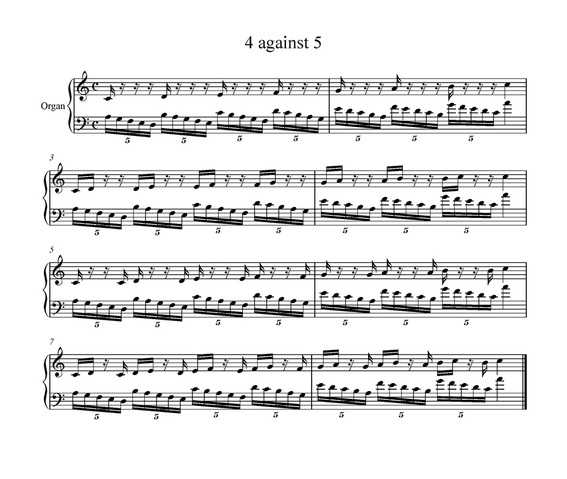

A few problems are as difficult as rhythm when you play the organ. Usually rhythm starts to be challenging when something changes in your piece. As long as an episode moves in similar rhythmical values, you're OK. You figure it out once and continue on autopilot. I remember such places especially when a section with eighth-note triplets transitions into eighth-notes. Like at the end of the 2nd page of BWV 546. When I was a student and first learned this piece that's the place where I got stuck rhythmically. I would involuntarily speed up, I think. The key is count out loud and always subdivide the beats. No, you can't rely on doing it in your mind silently, you have to utter the numbers "1 and 2 and 3 and 4 and" aloud. Otherwise you get carried by your own irregular playing. It's not easy for beginners, I know that. But there's no other way. In order to connect the rhythms of different episodes, you have to connect the pulse too. In response to the video 3 about playing 4 against 5 correctly, my friend Maik Schumann sent me a few of his additional tips which I thought you will find useful as well. So I'm reprinting Maik's recommendations (with his permission of course). NOTE: See the examples with music notation below. "In an additional practice step, I would recommend that you play the left hand (measures 3-4), and only add the notes 1 and 3 (in one quarter) of the right hand. Notice that the second sixteenth of the right hand is exactly between the notes 3 and 4 of the left hand (as you said). In another step, I recommend to add the note 4 (in one quarter) of the right hand (measures 5-6). This note should be just a little bit before the 5th note of the left hand (as you said). Then, in the last step before putting all together, play the notes 1 to 3 in the right hand (measures 7-8). Notice that the second note is just a little bit behind the second note of the left hand (as you said). Put all together (and all the same with reversed voices). I think these extra steps in practising are helpful when dealing with these complicated rhythms." I tried Maik's recommendations this morning and they really work. The whole thing together is very easy and pleasant after such preparatory steps. Try these tips in your practice and let me know if they have been helpful to you. By the way, after I played Maik's exercises, I thought of a few more things BASED on his idea of taking 4 sixteenths apart. Here they are: Of course, one could think of even more exercises BASED on these, too (in order to excaust all of the possibilities of 1 note, 2 notes, and 3 notes in the right hand part) but I think we can stop here and start practicing. Enjoy!

This is the final video 3 from the series of playing complex rhythmical figures. I hope you have found video 1 and video 2 useful. They dealt with playing 2 against 3 and 3 against 4 respectively so if you missed them, just watch them before going into video 3. So today let's take a closer look into even more advanced figure 5 against 4 and vice versa. Basically, in one hand we will have the sixteenth notes and in another - sixteenth-note quintuplets. It is not so difficult to understand intelectually where exactely all the notes have to go, but in reality playing this figure correctly is really complicated task. I hope this video will make it easier to understand how it's done. This is a second video in a series of 3 videos about how to play complex rhythmical figures. Yesterday I explained common cases about 3 against 2 and vice versa. Today it is time for 3 against 4. These rhythms are far less common but much more difficult to master. You can find a real-life example of it in the 2nd Movement called "Alleluias sereins" of l'Ascension by Olivier Messiaen. I hope this video will make your practice easier for you. Tomorrow we will deal with the curious cases of 5 against 4 so stay tuned if this topic is useful to you. |

DON'T MISS A THING! FREE UPDATES BY EMAIL.Thank you!You have successfully joined our subscriber list.  Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas

Authors

Drs. Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene Organists of Vilnius University , creators of Secrets of Organ Playing. Our Hauptwerk Setup:

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

This site participates in the Amazon, Thomann and other affiliate programs, the proceeds of which keep it free for anyone to read.

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed