|

As organists we usually think about the end result of our activity - organ recital or church service playing. When we perform a recital, we do it in public, and let our listeners interact and engage with our art.

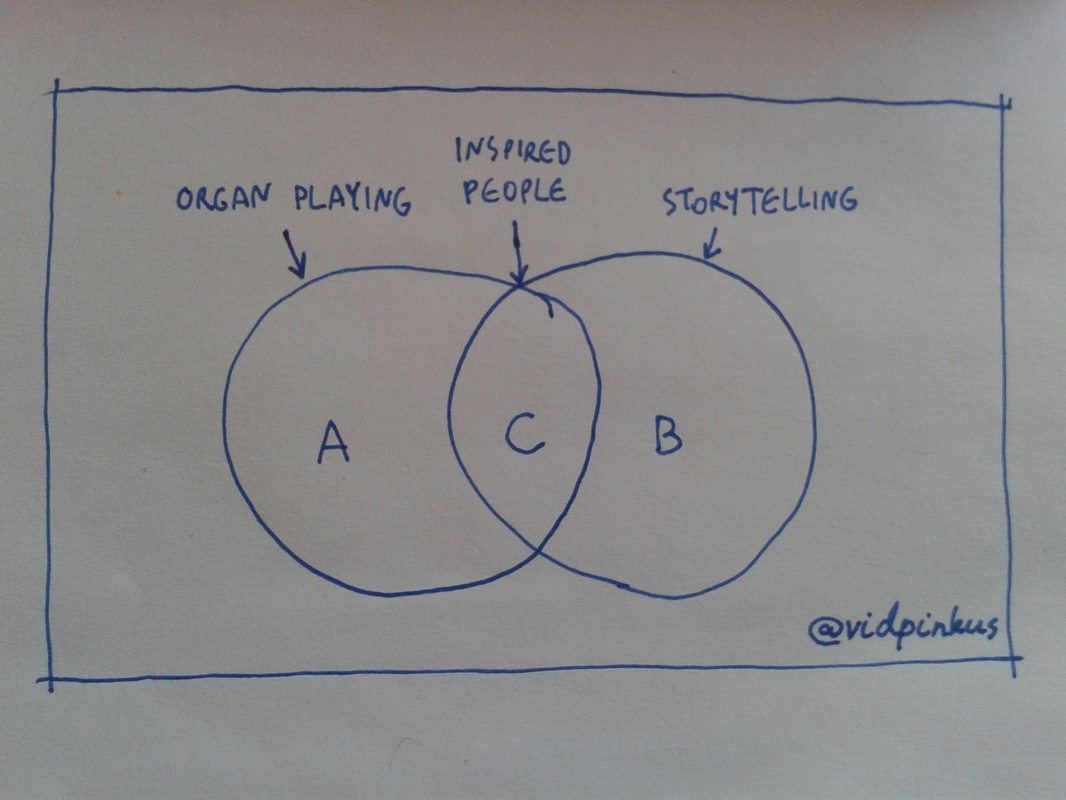

This is stock. We share the things that are valuable long-term, the things that we want to be remembered after decades of work. But there is another kind of sharing and it's called flow. It's a day to day process that leads to stock, our daily behind-the-scenes work out of which our stock is born. Flow also needs to be shared to help deepen our impact and empower our greatest fans to spread the word for us. If we ignore stock, our work begins to be shallow and our creativity suffers in the long term. If we ignore flow, we become invisible to the outside world. As Austin Kleon says, we need to maintain our flow while working on our stock in the background. This is one of the main principles for showing our art.

Comments

It's so sad to see 150 people come to your recital and realize the majority of them you see for the first and the last time.

That's right, you put so much effort into preparation of your event and yet when the next time comes for you to play, you have to start from scratch all over again. Seems like not quite efficient use of energy, isn't it? Imagine what would happen if people who came to listen to you play would crave to know more about your work you do and you could deepen your relationship with them over time? Think about this: What do you want your listeners to do while you are playing organ? Seriously, tell them. Tell them between your pieces yourself what they could listen for or write these things in the program notes, if you are not comfortable speaking. What do you want them to do after the end of the recital? Obviously you would want them to know more about your work and to keep in touch with them so that you could take them on a musical journey the next time. So include a compelling call-to-action at the end of program notes to visit your blog (maybe because you offer them tons of your videos or maybe the video of today's recital or maybe to read about what are you working on etc.). Again you can tell all of this before the last piece in the program. What do you want them to do once they are on your blog? Of course you want to convert them from first time visitors to someone who sticks with you in the future. So you have to have a way to connect with them, right? Something like newsletter subscription form. Once you publish something new on your blog, your subscribers will get it via their email. What do you want them to do once they have read your newsletter? Probably engage with it, share their thoughts, and talk about your work to their friends. All of this is connected - from your performance to their actions during your playing to the last call-to-action to your blog to email newsletter to their conversation with their friends. It's a two-way conversation. And it happens outside the recital, too. So take people by the hand and help them follow through your musical journey. How do you help your listeners appreciate more the work you do? Share your thoughts here. Nothing is worse for an organist than this feeling of helplessness when you know you have to play an organ recital in a few months but you don't have enough pieces mastered and you are a slow learner. Should you cancel the recital ahead of time to be polite for the organizers or is there some kind of other choice you could make?

I think there is, and I'd like to say special thanks to my friend John Higgins who pointed out this solution to me. You see, you don't have to play all newly mastered pieces for your recital. And you don't have to play pieces that somebody else wrote at all. Let me explain. First let's calculate some timings here and aim for an average 60 minutes organ recital. More than that would be difficult for the listeners. You could play a shorter recital but for the sake of example let's keep it around 60 minutes. Think of the title of your recital. Choose about 3 words for the title to keep it easy to remember. This is crucial for publicity campaign you will be doing a few weeks before the recital so that people would actually want to come to listen to you play. If you don't have a coherent theme or topic which would keep all the pieces under one umbrella, you can choose a name of one particular piece as the overall title of your recital. If you have some previously prepared compositions under your belt, now it would be a great time to refresh them. Find as many contrasting pieces that would work together for this theme and that you would want to play and calculate the time. Maybe you will have 15 minutes this way, maybe 30 minutes. Let's stick with 15 minutes for now. Then if you have a couple of months left, perhaps you could learn a piece or two from scratch. Let's say it would be 5 minutes. So now with the new piece you have 20 minutes total. What to do with the rest of 40 minutes? If you have some hymns that your listeners would enjoy, choose 2 or 3 settings and play a few verses of each. This would be around 10 minutes. To make hymn playing more interesting choose different registration for each verse and place the hymn tune in a) soprano, b) tenor, and c) bass. For the soprano it's easy - open your hymnal, take a solo reed stop or Cornet with the right hand, place alto and tenor in the left hand on the softer registration and play the bass with pedals on the 16' stop as the basis. When the tenor has the hymn tune, play it with the left hand one octave lower with a strong reed, such as Trompette and place alto and soprano in the right hand. You can still use the hymnal for this but hymnal's tenor becomes your soprano now. The pedals still play the bass. When the bass has the hymn tune, play on Principal Chorus registration with mixtures and with the addition of Posaune in the pedals. But here's the tricky part - you can't use the harmony from the hymnal. You have to re-harmonize it. It's best to keep 3 upper voices on the same manual and moving in the opposite direction than the bass. This way you will avoid forbidden parallel fifths and octaves. 30 minutes left now. You see how we have calculated the choices for the half of the concert. So far so good. Now here's what I would recommend next (and this may sound scary for some of my readers). You could improvise. That's right - you could improvise a piece or a few pieces during your public concert. If you have never improvised in public before then you either a) practice improvising a lot in private first or b) postpone improvisation for the later date. It's really up to you. Only you know your strengths and weaknesses. But if you choose to improvise a piece or two, then your listeners would be amazed, especially when you tell them that this is the first and only time they will hear you perform this way for them. Because the next time your improvisation (if it's a true improvisation) will be different. You could improvise on the hymn tune that they know and appreciate. In this case you can improvise a chorale prelude or chorale fantasia on some known hymn tune. Alternatively you could choose your own theme. Stay with the form that is coherent and easy to follow. An ABA form usually works best as well as ABABA (if subsequent B and A parts are shorter and in other keys than in the beginning to keep it interesting and engaging). Remember, you could improvise on a well-known story, perhaps a folk story or a legend or a story from the Bible. Then your job is to depict this story with musical means. In this case the form will be much more free. Keep the registration changes and texture constantly changing to fix your listener's attention. Embrace the power of modal improvisation. It works for almost any occasion. Storytelling improvisation can be quite long, if you can keep it exciting and full of surprises. You can even fill the entire half of the concert with this. Besides improvisations, you can demonstrate the organ at your venue. Again organ demonstrations can be long but you can do it a brief version in 20-30 minutes. Here too, improvise on separate stops showing off the colorful side of your instrument. Demonstrate different families of sounds - principals, flutes, strings, and reeds. Combine stops in surprising and fresh ways. Don't hesitate to use 4' flutes - usually every organ has at least one nice flute of this pitch level. Show the deepest and the highest sounds the organ can make. Now the best part in this is storytelling. To keep your listeners wanting for more explain briefly how the organ looked like in ancient Greece, in the Middle Ages, and other periods in history. Explain how the mechanics of the organ work. Tell them even about how the sound is produced, about the pipes and their materials and construction. Tell a personal story or two about your experience with some aspect of the organ. Invite people to see and touch the organ from up close. Some of them may even try to play it with their hands and feet. Although this is improvisation too, remember to practice it diligently. Maybe prepare one demonstration first for your family members and then for your closest friends one month before the real recital. This would feel like run-through before the big thing. It will expose any weak areas in your recital that would require more practice and work. If you are not sure about improvisation, the great thing about demonstration is that it can be done quite effectively almost entirely on hymns people know and love. If you spend about 1 minute on one stop, then that's perfect - that's the duration of 1 verse of the hymn. To keep hymn demonstration more interesting, you can play one hymn in different keys and in different modes (major/minor or any other). New colors will be a great surprise to people. If you want, you can use 3 hymns this way for the entire demonstration. And don't forget to vary the texture from time to time playing in 2, 3, or 4 voices, placing the tune either in soprano, tenor, or bass, and changing the rhythm and meter of the hymn tune from double to triple. Prepare to answer people's questions after or during the demonstration because there will be many (if the listeners aren't shy and if you do your storytelling with enthusiasm and good articulation). So you see, how you can use your constrain of lack of time and repertoire to your advantage and plan your recital very creatively. But make no mistake - these recommendations will still require a lot more time than you think to prepare, but perhaps less than learning new pieces for the entire recital. Above all remember that your contagious passion in communicating stories that resonate with people will inspire far more hearts than your organ playing alone ever will. Did I miss something? Share your ideas in the comments. [HT to John] Troubling situation, right? Obviously you want to progress in organ playing in building up your technique and repertoire but various time constrains (work and/or family responsibilities) make it seemingly impossible to do so.

You might have just enough time on the organ bench to repeat previously learned material and to keep it on the back burner so you are kind of stuck. You are not regressing but spinning your wheels. But since time goes by so quickly it feels like your technique might even degrade when you check your progress from one week to another. And without actually making progress, you can't learn new pieces, can't hope to prepare for organ recitals and even church service playing is becoming harder and harder to sustain, let alone to make it engaging and interesting. So that's the constrain you are facing - you want to advance but don't have enough time. Seems like hopeless business? Not the way I look at it. A question to you: Do you have at least 30 minutes a day for your organ practice? If not, it would not be realistic to hope progressing as an organist. So first you have to make some time. Will you agree with me that if you are truly serious, 30 minutes a day can be found perhaps by getting up earlier or staying up later than others in your family, or cutting back on your online activities or skipping your favorite TV shows, or processing your email inbox in batches just once a day instead of keeping your inbox tab open all the time? But this post is not about how to find more time for practicing organ. We just need to agree on the minimum of 30 minutes a day on the organ bench. Of course, I'm not suggesting that every organist would only play for half an hour. No, this advice is for emergencies only, when you're drowning in work and responsibilities but you still feel a need to practice. OK, here we go. First, you need to practice the right kind of materials. Fiddling around with sight-reading or playing a hymn here and there won't make the cut. You need to focus and play what really matters to your technique and of course to your goals as an organist. We'll pretend you need to learn some new pieces and advance your technique. With regards to technique, I personally like practicing Hanon's the Virtuoso Pianist exercises but they take much more than 30 minutes a day, perhaps an hour or so depending on your speed. Some people find Hanon to be boring and the exercises musically too dry and uninteresting. I too, tend to play only what's engaging to my mind. So I play Hanon in various modes and rhythms. This helps me avoid boredom in practice and at the same time learn new modes which I later incorporate in my improvisations. But you have only 30 minutes, right? This means you have to look at Hanon exercises strategically and figure out what's 20 percent of these exercises that give you 80 percent of results. That's 80/20 rule, or even 90/10 rule. In my experience (and your experience might be different), exercises in scales in double thirds (from Part 3, No. 52) are the ones that require the most stamina, they are very tiring to the fingers, and consequently make them very independent. That's right, out of this book, if I had to choose only one exercise, I would choose exercises in scales in double thirds. Of course you can play in different keys, in different modes, and in different rhythms and even meters to make them more interesting, challenging, and rewarding. Be careful not to overwork your fingers (at least at first). Start your playing slowly enough to be comfortable and trust that speed will come over time. Rest and relax when you feel tension rising. But this is not all. Spend only 15 minutes a day with these exercises in double thirds. The best part is that you don't even need an organ for that. You can practice on piano, on the table, or even on your lap while watching TV commercials. To make this practice even more inclusive, play pedal scales in parallel and/or contrary motion at the same time when you practice manual scales in double thirds. If your pedal technique isn't good enough, start with playing pedals at the ratio 1:2 or even 1:4. This means playing 2 notes on the manual and 1 on the pedals or 4 notes on the manual and 1 on the pedals. So those 15 minutes don't count into your 30 minutes organ practice regimen. You see what's wonderful - you are advancing your manual and pedal technique even while being away from the organ. But now let's go back to our practice. You need to learn new pieces and to refresh your muscle memory of the old ones and you've got 30 minutes for this. Here's what I recommend - practice for 15 minutes previously mastered material and for 15 minutes learn something new. When you repeat previously mastered material also don't play the entire piece but practice in shorter fragments repeatedly in a slow tempo. But since you don't have a lot of time, stop after 15 minutes and go to the next phase of your practice. In those time intervals when you're learning something new, don't aim to play the entire piece, though. Be very focused and strategic - play only those measures which you are learning, maybe 4 measures. That's it. Truly master them during 15 minutes. It's possible, if you're serious about it, if you're learning in single parts, in combinations of 2, 3, and 4 parts and repeating very slowly until you can play at least 3 correct repetitions in a row of that fragment. So you see at least in theory, how it's possible to advance in organ playing even though you don't spend much time on the organ bench. Of course, if you can find more time for playing the organ, that's even better - you can incorporate sight-reading, improvisation, harmony, counterpoint, transposition, memorization, learn more new fragments and repeat more old ones, play many more technical exercises etc. However, in this post I only was concerned with a bare minimum - learning a little bit of new material while retaining old one and polishing your manual and pedal technique to the degree that you feel you are advancing and not spinning your wheels. Try this system yourself for a while and let me know how it works for you. [HT to John] So you have written a nice collection of organ music and have submitted to a few music publishers and nobody wants to publish your music? Does it mean your music is bad? Does it mean you should stop composing?

Music publishers might reject your music for one of two reasons: 1. Your music isn't the right fit for them. 2. They are not the right fit for you. Although you might think that your organ compositions are wonderful and worthy of receiving the light of day, you must remember that music publishing houses receive thousands of submissions and look at your pieces strictly from their commercial point of view: Will it sell? Here's the question. Will they be able to publish it and make a profit from it? So if they think that the answer is yes, you might receive a positive answer and if they don't believe that your music will be the right fit for them - you might even not hear from them about their rejection (sadly). So in order to receive a positive answer, you should first think about why they think your organ music will sell or not. Scores of organ music, just like anything else can be sold based on these 3 things: The right kind of people know them, like them, and trust they can solve their problems. People must know your music, they must know you exist. If they don't, you're invisible to them. It doesn't mean your music is good or bad, it just means they are not aware of it. Once the right kind of people know about your music, they must also like it. Think about yourself - do you ever buy music scores of composers whose music you don't like? Not likely, unless you buy for the future reference, unless you know the composer is too important to ignore. But in general, if you buy some music scores, you like the music. Once the right kind of people know about your music and like it, they must also trust you enough that your compositions will solve their problems. What do I mean? Well, every organist who is on the lookout for new music, has some problems, such as "I don't know what to play for my church service next month", or "I don't have suitable music to play for Christmas service", or "I do have some collections of Christmas music but they are too difficult for me", or "Organ music collections suitable for Christmas I have sound musically dull. Therefore I need something more interesting". That's an example about Christmas organ music but it can be about anything. So if they believe your music will help solve their problem, they might consider buying it. Of course, you can always publish your compositions yourself. Amazon Self Publishing platforms make this process very simple. Unless you've done much of the preliminary work I write about later in this post, this doesn't mean your music score will sell, though and you will receive royalties. But if you still think you need a conventional publisher to get your musical ideas to spread, here are some things to consider you can do to get on the radar of the right kind of people, help them like your music, and help you earn their trust: Create a website with a blog. If you are not online, the right kind of people will have a hard time finding you. Sure, you can have an active profile on social media sites, but they are not places you can control. Your website with your domain name is what nobody can take away from you, if any of these social media sites change or go out of business, or you get locked from your account or whatever. Today this process of creating a website is too simple even for non-tech people, like organists, to be an excuse of ignoring it. Basically you can be online in 25 minutes or less. Just google "how to create a website and a blog" and you'll see. Think about who you are trying to reach. Sure, they are representatives of specific music publishing houses. But what are their hopes, wants, needs, fears, frustrations, and problems? Be as specific as possible. Think about where the people you are trying to reach are gathering online. What blogs do they read, what social media sites do they interact at, what forums do they have their discussions at, what podcasts do they listen to, what journals do they read. What conferences do they go to? Try to be helpful and inspirational on some of these places always linking back to your main site. You can convert your music files into PDF's and sell them directly from your website or external platform, such as Score Exchange. You can also convert your scores into videos and publish them on sites like YouTube or Vimeo. You can perform your own music and record videos of them. You can talk about and analyze your compositions, reveal your compositional process in these videos as well. In the description of each video, make sure you include a link back to your site where they can get more information about you. You can also offer some collection of your scores for free in exchange for people's email address. For this you need a newsletter service, such as Mailchimp. Once you have newsletter subscription form set up on your website, you can begin to produce more videos of your music compositions and publish them online. A few videos won't make any difference but the more videos you have, the better chances people have at finding your work online. Of course, don't stop here. Embed these videos on your website and in your blog posts talk about the behind-the-scene work you do while you compose. What's inspiring to you? What problems and frustrations related to your work do you have? Don't try to appear superhero. Be human, someone people can relate to. Regularly distribute your work on social media sites in the format and form that is native to that particular platform. What works for Facebook will not necessarily work for Twitter. What works for Twitter, will not necessarily work for LinkedIn. You can share in formats of text, pictures, video, or audio or any combination of them. Form can include a link, a question, a poll, an idea etc. The great thing about newsletters is that people can subscribe to them and you can automatically convert your blog posts to email messages that will be delivered to your subscribers (like this blog, for example). What else? Always be generous and helpful to people. These two things alone over time will help you build a reputation that will precede you wherever you go. When you have a terrific reputation of always exceeding expectations and over-delivering, the time will come when the right kind of publishers will start to approach you. So basically you have to be so good that they can't ignore you. And because the myth of overnight success is something we always want to believe, remember that it takes at least 3-7 years (sometimes even more) of relentless hard work to build your profile online so don't expect quick results. You see, you might think about publishing your new organ compositions as the publishing problem, the reality is that more likely you have idea-spreading problem. Above all, if organ music composition is something you love, keep up composing and keep perfecting your craft. In a world of too many options and too little time, nothing will help spreading your idea, if your work isn't remarkable enough. Welcome to the Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast #3!

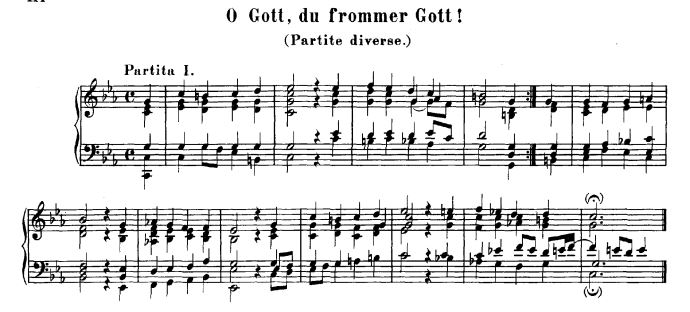

Listen to the conversation Today's guest is Pamela Ruiter-Feenstra, organist, teacher, composer, and a world-renown expert on improvising in the Bach style. I had a privilege to study with her at Eastern Michigan University for my Master's degree but her enthusiasm for historically inspired improvisation caught my attention even earlier, back in 2000 when we met for the first time in Gothenburg, Sweden at the Goteborg International Organ Academy. Improvisation in the Bach style has been a life-long pursuit for her and in this episode she shares her insights about improvising chorale-based works of Bach on any keyboard instrument, which is the focus of Vol. 1 of her book "Bach and the Art of Improvisation". Enjoy this inspiring conversation and share your comments below. If you like these conversations with the experts from the organ world, please help spread the word about the SOP Podcast by sharing it with your organist friends. Relevant links: www.pamelaruiterfeenstra.com "Bach and the Art of Improvisation", Vol. 1 (book review) "Bach and the Art of Improvisation", Vol. 1 - the book Practice the above "O Gott, du frommer Gott", BWV 767 by Johann Sebastian Bach this way:

Take a slow tempo, aim for a detached articulate legato touch and 3 correct repetitions in a row. Here are the chords of this harmonization: C minor: i-i-V-i6-V6-i-i-V65-i-v6-VI7-iv6-V-V-V6-i=vi-vii6-I-(vii6)-V-I-vii6-I6-ii65-V7-I=III-i-i6-V-IV6-V65-i-(V42)-iv6-i64-ii65-V-I Question: Could you take these chords and play them in a different key, say in D minor? Nobody has enough time to practice organ playing.

That's right. Even if you have all the time in the world (which most people don't), it seems like you would still enjoy some more time at your favorite instrument. It's a wrong question to ask, I think. Far more productive would be to figure out the way how to stop doing meaningless stuff and focusing on what really matters. The famous 80/20 rule - do the 20% of the activities that produce 80% of results that go towards your goals. And remember, you don't have to do everything every day. Just figure out what's the easiest next step and do it. Sometimes when you're brave enough, you can leap through several steps at once. And these constrains that you face every day - your family responsibilities, your work responsibilities, your health problems, they become your allies because they help you become much more focused on your organ playing goals and think about not what's not possible but about what's possible within the time frame you have. The thing is we often freeze when we face these constrains and fall into a victim's mindset "I wish I could do that but I don't have time", "I wish I could do that but I'm to old to change" - and so we even refuse to do the things we could that could potentially also lead us closer to our goals. Adam Morgan and Mark Barden in their book "A Beautiful Constraint" suggest that the way we find the way out of our constraints is this: we could start asking propelling questions like these (I adapted them to organ playing situation): How can I find more time to practice organ playing without sacrificing my family and work responsibilities? How can I make progress in playing the organ, if my illness prevents it? How can I double my progress in organ playing while halving the time I put into practice? How can I improve my organ technique without playing boring technical exercises? How can I learn to improvise without feeling stupid and embarrassed because of mistakes I would make in public? How can I push through the challenges that I'm facing without feeling overwhelmed by them? And the way you figure out the answer to these kinds of questions is by giving an answer which starts with Can-If approach: I can find more time to practice organ playing without sacrificing my family and work responsibilities, if I reduce the time during the day I check my email and surf the internet and the social media sites. I can make progress in organ playing even with my illness, if I just practice for very short periods of time which will not feel exhausting (and if I start to think about how my skills can help other people which would take my mind from thinking too much about my own health condition). I can double my progress in playing the organ while halving the time I put into practice, if I practice the right kind of musical materials. I can improve my organ technique without playing boring technical exercises, if I make these exercises not boring and very creative. I can learn to improvise without feeling stupid and embarrassed because of mistakes I would make in public, if I start playing just for myself and then for the small group of friends who trust me and want me to succeed. I can push through the challenges that I'm facing without feeling overwhelmed by them, if I can focus on just one step at a time. By asking the right kind of propelling question (and thinking up the new, even more challenging ones), you can figure out the answer with the Can-If approach in almost any constraint, in almost any situation. That's when constraints become beautiful and you graduate from a victim's mindset to the one of transformer's. That's when people around you will start being jealous of you, laugh at you, or even fight you. That's also when others will start to look up to you and follow your lead. That's how you begin to change (your) world. Start today because you'll never have enough preparation for this anyway. Don't try to be him or her, though. Try to be you. Try to be your own category, try to be the one that others will want to copy and follow. Find your own voice.

As M. Gandhi said: "First they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, then you win". But this is of course one of the hardest things for us, to discover who we are, to find our own category, to be something worth following. Here's the thing: You won't know (and I won't know and nobody else will know) if this is your true voice. Because the minute you think you found it, you need to strain to look for something new that challenge you enough. I don't think there ever was a time in Bach's life when he told to himself - "this is it, this is the Bach's style which I will be known for centuries. I've done it, I'm going to retire now." No, every day he sat down at his table and wrote something. The writing/playing/improvising doesn't have to be great. It just have to be yours. You won't know if it's great, if it's remarkable, if it's worth spreading. Others will decide its worth, if you let them. But first you have to figure out what's your purpose for playing organ, what's your mission as an organist - is it just for your own pleasure, or you want to share your skills with friends and family, or play at church, or perform organ recitals, become an improviser, a composer, a creator. But think beyond what you want to do, think about what your act as an organist will do to others. Although finding our true voice seems like a massive undertaking, it usually gets down to the things that are at hand - taking that first step. The step you are most afraid of, the piece that scares you the most, the improvisation practice that you are putting off for weeks etc. If you can concentrate on just one step without thinking too much about the future (but holding it in your sight), then you can take another step tomorrow. Sometimes you don't know what this step is. Most of the time, I say. Then you leap. Leap into the dark without knowing where you will land but trusting that in the end it will be OK. When we look up at other organists who excite us, whom we want to follow, if we were to ask them, the best of them would still say things, "I'm still learning", "I'm not sure what I'm doing." Because the minute we stop learning, the minute we are sure of something, we stop progressing not only as organists but also as human beings. Just be helpful to others and whatever you do, assume a digital-first posture (meaning share your work and process online). This will help your work and insights to spread. I think in general, whatever we do, our mission is to become artists, to change (our) world, to make it a better place for everyone around us. There's no recipe for this. If there was one, everyone would do it, and it wouldn't be as valuable. No map, no step-by-step instructions. Only a compass. Eventually you'll figure this out just by doing, if you stick to it when they ignore you, when they laugh at you, when they fight you, when you win. But of course you would have won a long long time ago - the minute when you learn how to give. Yes, even today. Especially today. Do work that matters. Share. Repeat. [HT to John] Just a quick note - because many of my subscribers asked for it, this morning I've finished writing in fingering and pedaling in Widor's Toccata for easy practice. If you like this piece and plan to learn it, now is the best time because this score is with 50% discount until the end of August.

Check out the score |

DON'T MISS A THING! FREE UPDATES BY EMAIL.Thank you!You have successfully joined our subscriber list.  Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas

Authors

Drs. Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene Organists of Vilnius University , creators of Secrets of Organ Playing. Our Hauptwerk Setup:

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

This site participates in the Amazon, Thomann and other affiliate programs, the proceeds of which keep it free for anyone to read.

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed