|

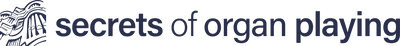

Would you like to learn Andante in Db Major by Cesar Franck from L'Organiste? I hope you'll enjoy playing this piece yourself from my PDF score. Thanks to Alan Peterson for his meticulous transcription from the slow motion video. What will you get? PDF score. Basic Level. 1 page. Let me know how your practice goes. This score is free for Total Organist students. Check it out here

Comments

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas!

Ausra: And Ausra! V: Let’s start episode 446 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. And this question was sent by John. He writes: “Hi Vidas and Ausra, How are you today? Soon I would like to start learning Noel X by Daquin as we discussed a few months ago. Could you please give some guidance and teaching on these points? How to play the French trills in this piece? Please spell out exactly what notes to play. When to play pedals, and do you double the left hand in this case? How to play the fast arpeggios in the left hand accurately especially on page 4? What registration would you use on a small two manual English style organ? I hope if I start learning soon then I can have it ready by Christmas this year! I really enjoy listening to you play this piece in your Christmas Concert at St Johns I think in 2016. I have read your podcast SOPP346 which has some great advice! I hope you have a great day! Take care, God bless, John...” V: So, John starts his question by asking how are we today. How are you today, Ausra? A: I’m fine. V: What does it mean? A: It means that I am fine. V: Excellent. And how am I today? A: I don’t know. V: So ask me! A: How are you today? V: I am excellent, today. And do you know why? A: I know why, but I don’t think everybody would have to know why! V: Because, I played two concerts this week. One was on, I think, Wednesday, for a group of Canadian tourists, and I also played, yesterday evening, part of the concert together with the Finnish choir in our church. I supplied two improvisations for them. A: And you will play tomorrow in Kėdainiai. V: Yes. Kėdainiai is, basically, right in the center of Lithuania. Medium sized town, which has at least two churches, and two historical organs. And I will be playing organ improvisations as part of the opening of the exhibition of one of the most famous painters in Lithuania. Aloyzas Stasiulevičius is his name. So anyway, John is working on Noel X by Daquin, and is wondering about the French trills. Ok? What is the main feature of French trills? How do you start? From the main note, or from the upper note? A: If we are talking about trills, then you start on the upper note. If we are talking about mordents, then you start on the main note and play with the lower note. Basically, the same rules apply for French Baroque music as for J. S. Bach. I think we have talked about it a number of times, that Bach played his ornaments according to French tradition. Don’t you agree? V: Of course. Yes. Obviously. Obviously, French trills need to be played most of the time from the upper note, and in this piece, yes, we have so many French trills, and I think that we can discuss a little bit of mordents, too, because there are some mordents playing on the main note, but then adding the lower note, and coming back to the main note. So, let’s say on page 4, the first measure is the mordent on the note C. So, I wrote C-B-C with 2-1-2. Or in the second line, second system of that same page and second measure is the note E with mordent, so E-D-E, 3-2-3. You see? But there are trills, like in the third system on that page, so this means we play from the upper note. A: That’s right. V: It’s written on the note A, so we start from the note B. B-A-B-A. Probably 4 notes. A: And for a place like this, actually, you could do even a double trill, longer. That’s like in the D minor Toccata, for example, some organists play only one repercussion, but some do two repercussions. V: There is an interesting trill on the same page where both hands have to play a trill for more than two measures. A: How would you play it? Would you play it exactly rhythmically? V: No. A: I thought so. I also wouldn’t play it rhythmically, so how would you play it? V: Well, before we play the trill, I have to tell a little bit what’s happening before that trill, right? Before the trill, we have at least one measure of both hands playing in parallel thirds right here, and even a half measure before. So, in 16th notes, it’s a fast passage. Basically, it’s a diminution on the minor and major third. The left hand plays from the beginning of that measure B, and the right hand plays D. Right? So the hands move up and down in parallel thirds. And then in the next measure it lands on the same minor third, B-D. But it’s a long trill. And I’m wondering whether we should play it from the upper note or not, because the trill actually starts a half measure before: D-E-D-E-D-E-D-E A: So you have to just continue and accelerate the tempo V: Absolutely. Yes, starting from the….. A: And then of course slow down at the end of it. V: Starting from the main note, I think, in this case, A: Yes, in this case yes! V: because it’s a continuation of the same trill, which was spelled out a half measure before, and then you have to accelerate, as Ausra says, and then slow down. How would this make sense? Okay… A: But the best thing, I think, is to listen to recordings of this. V: Obviously yeah. If John listened to our rec...to my recording…. Haha, I said “to our recording,” as a duet, it would be funny. I would play the right hand and you would play the left hand! A: Yes, very tricky! V: Yeah... [This conversation continues in the next podcast episode. Stay tuned...] Thank you everyone for participating! You all made us very happy with your entries. Ausra and I selected the following winners. You can congratulate them here:

https://steemit.com/@organduo/winners-of-secrets-of-organ-playing-contest-week-23 Have you ever wanted to start to practice on the organ but found yourself sidetracked after a few days? Apparently your inner motivation wasn't enough.

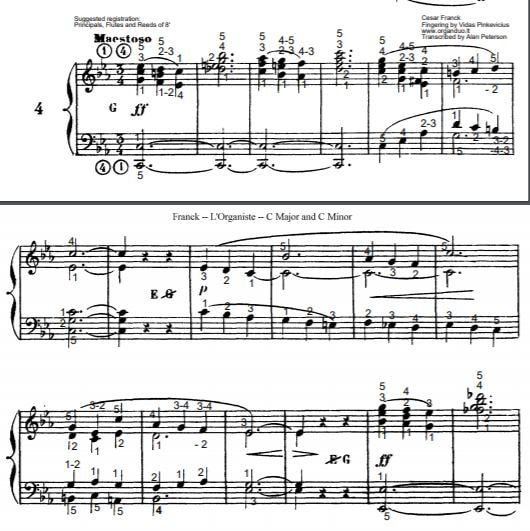

I know how you feel. I also was stuck many times. What helped me was to find some external motivation as well. In order for you to advance your organ playing skills and help you motivate to practice, my wife Ausra - @laputis and I invite you to join in a contest to submit your organ music and win some Steem. Are you an experienced organist? You can participate easily. Are you a beginner? No problem. This contest is open to every organ music loving Steemian. Here are the rules Would you like to learn Poco Lento in C Major by Cesar Franck from L'Organiste? I hope you'll enjoy playing this piece yourself from my PDF score. Thanks to Gerrit Jordaan for his meticulous transcription from the slow motion video. What will you get? PDF score. Basic Level. 1.5 Pages. Let me know how your practice goes. This score is free for Total Organist students. Check it out here

Vidas: Hi, guys, this is Vidas.

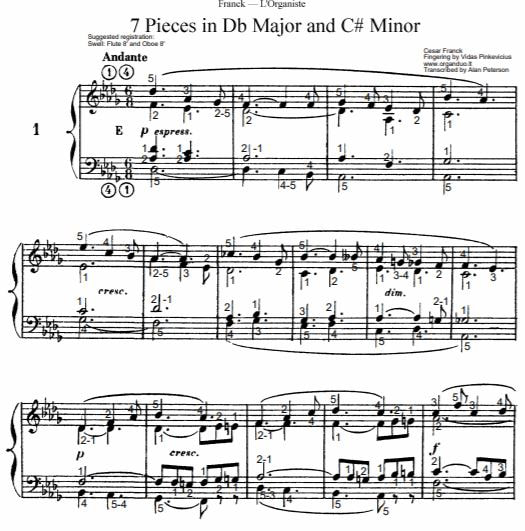

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 440, of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Carlos, and he writes: Thanks a lot Dr. Vidas and Dr. Ausra. Well, the primordial matter that I would like to reach in organ playing it's a fine performing level in public. One thing that I think it holds me, and also a matter of my capital focus it's the control of the nervousness in performance. I think that there is a lot of technique to control the panic in scene, I have used some of them and they work well, but I'm sure that you have some great hints for prepare the mind to get a major level for focusing one self in public performance. Thanks a lot for your course, it's pretty good and accurate. Greetings to you all! A: Well, okay, Dr. Vidas... V: Dr. Vidas. A: What can you tell us? V: Dr. Ausra, I think you all also have some experiences, right? A: In what, nervousness? V: (Laughs). A: Yes, we all do. I guess the main reason is a question you need to ask yourself—what causes your anxiety. Because, well, the reasons may be various, but I think one of the most important is that you are not prepared as well as you should be. V: And this is right that you are saying this of course. But to be well prepared means a lot of different things to a lot of different people. Right, Ausra? Because, how many times have you been in such, in a classroom setting, when your kids, your students said, ‘oh, I practiced for hours and hours, and I could sing it if it’s an ear-training class, sing it without mistakes at all at home. But now I cannot do it in class’. A: They are lying. That’s what I realized after teaching for so many years. Because either they, if you practice for so many hours as you said and you will still could not do it, it means something is really wrong with you and maybe musician path is not your path. V: Mmm-hmm. A: Or you a little bit exaggerated the hours of your practice, which is I think more often the right case. So, of course we are all human beings and we might all experience some sort of panic during the actual performance, and there [are] always things that might happen with the instrument, or with yourself, or with your audience, or something that might not go as well as it was planned. But still I think anxiety, to have some of anxiety during performance, it’s a normal thing. And I don’t think it’s good to get rid of it entirely, because that fresh adrenaline, it gives something really vivid to your music. V: Vitality! A: Vitality, yes, to your music. V: Mmm-hmm. A: And excitement and audience gets it and it’s really fun—all this experience. So I think some of anxiety is really good—it helps you. Because otherwise your music might sound boring if you will play it like a machine, let’s say like [a] Sibelius program—it always plays no mistakes, no tempo changes, everything is perfect, but it’s dull and it’s lifeless. V: You could write down accelerando and ritenuto and they could play back to you with fluctuations in tempo of course, but that’s about, not everything the program can do today. I guess that the software is getting better and better, but to reach human interaction level, I don’t think it can, yet. A: So, basically, I could say what I do to Carlos, in order to help myself. So my first thing is I really try to prepare very well for my recitals, that I would be really confident that I did everything what I could. It means if I know I will have to perform, I need to practice in advance. V: Mmm-hmm. A: Because you always have to leave some time for yourself just in case you will have some unexpected things happening in your life. V: Imagine if you are a professional musician like yourself, but not at your level, but at the student level. But still you’ve been learning the organ and music for maybe, I don’t know, fifteen or more years, yes, before going to America. But even then Dr. Ritchie suggested you to be ready at least one month before your recital, to have a run-through one month before. Is this realistic, Ausra? A: Yes, this is realistic, I think. And that’s the way how it should be I think. V: Mmm-hmm. Would that help? A: Yes, that would help. V: To you. But for people who are not professionals and just playing organ as their hobby, I think two months are needed. A: Yes, that would be really wise. Another thing you also need to know, to breathe, during your actual performance. Because some anxiety comes during your performance, and panic attacks, because many people, especially inexperienced ones, simply forget to breathe. And breathing is crucial—it’s very important. So if you cannot control your breathe during performance then just take a few deep breaths before starting the peace and then maybe at the end of it, or maybe at the slow section of it—remember to breathe. V: It takes practice. A: Yes. It’s not so easy. V: Don’t expect to breathe during public performance when you never focus on your breathing during practice, right? Panic will do it’s own work and you will forget. Maybe you will remember a moment here and there, maybe, if you’re lucky. But if you really want to be free during public performance, you need to incorporate breathing into your daily routine. A: And the third thing which is very important, especially for those who have very few public performance experience[s] yet, you need to perform as often as you can. The more often you perform, the better you will get on the stage. V: Every ten recitals or public appearances, you will have a breakthrough. A: Yes, because, look, if you will perform often enough, you will get tired of being actually nervous, of having that anxiety, because you cannot be always afraid of it. V: Mmm-mmm. Remember Dr… A: It will become a habit for you to play in public and you will enjoy it actually. You want to be on the stage. You see some of the musicians, we are old, and we can hardly walk but we still want to play to sing in public—as they make not maybe a nice jokes about them that they will probably die on the stage. V: Remember Dr. Pamela Ruiter-Feenstra at Eastern Michigan University, told us about her experiences in Germany when she was studying with Harald Vogel. She would have to perform publicly at least once a week, or maybe more, I guess, for that time, maybe for how many months she was there. And that helped her to reduce the stress level to basically zero. It was like daily task for her. Nothing special. A: And the same in America when we had studio class every week and everybody in Lincoln, everybody would play what we have learned during that week. So that way you would have to perform in a studio class each week and then we would have to play service on Sunday, and sometimes even on Saturday evening. So that’s at least two public performance a week, not counting all kind of recitals where you would take either a part in the recital or you would play solo recital. V: Mmm-hmm. A: And that’s how you built up an experience. V: The reason I live stream my practices for example, from my church on the organ on Facebook, is that not only I want to promote the largest pipe organ Lithuania, not only I want to reach more people with my playing, but I also want to reach the confidence level of my public performance and the freedom it gives. That’s, it’s not a big deal, right, for me to play in front of the camera, or in front of strangers. It’s the same thing for me too. I know I won’t stop the camera at any time. It has to be live without editing and even if I make a mistake I will have to play around it so that my audience wouldn’t notice it. A: Yes and I think there might be some cases when people cannot overcome themselves, cannot overcome that performance anxiety and it’s just there and you can do nothing. In that case I would probably suggest for such a person, especially if it’s a young one, probably not to, not play any more. That’s very sad but I think there are some cases like this. I have seen kids who would keep just shaking and shivering and panicking, and, I think that because if it’s [a] case like this, and you cannot do anything about it, maybe it’s not your way to be a professional musician. V: I have to clarify this, because I know what you’re thinking; you’re suggesting that this person might play privately, not in public. A: Or just switch to another major. V: Mmm-hmm. Earn a living in a different way and keep… A: That’s right. V: playing an instrument as a hobby. A: That’s right. V: Yeah, if it costs you too much of nerves and stress, then it’s not worth the effort, probably. Unless there is a clear path to overcome this. A: True. V: Unless you’re seeing the progress in over the months and years of reducing stress, gradually. A: Because, anyway, I think music needs to give joy, and not nerve. V: Okay guys, this was a good question. So please send us more questions like that. We love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice… V: Miracles happen! Would you like to learn Maestoso in C Minor by Cesar Franck from L'Organiste? I hope you'll enjoy playing this piece yourself from my PDF score. Thanks to Alan Peterson for his meticulous transcription from the slow motion video. What will you get? PDF score. Basic Level. 1 Page. Let me know how your practice goes. This score is free for Total Organist students. Check it out here

Vidas: Hi guys! This is Vidas.

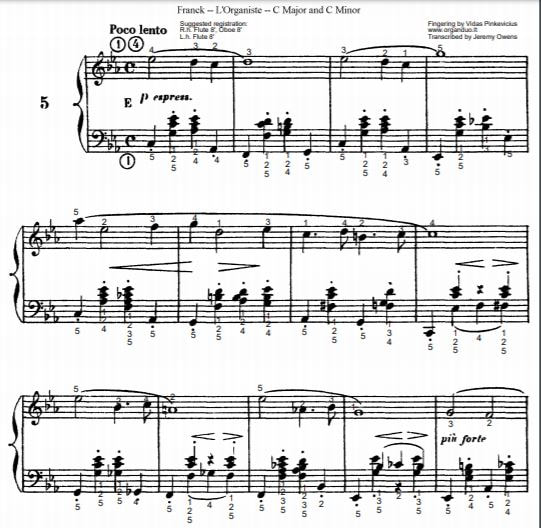

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 445 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Micky, And he writes: My dream is to be a good sight reader and solving the note quickly. My problem is when I practice I am good but when I go to play it in the church I don't play it good with accuracy. V: That’s a common problem, Ausra, right? That a person is good privately, but not so good publicly. I think we all are. A: Yes, true. That’s what my kids always say to me in the classroom – “Oh, I played it at home and I was so good. But now here I can’t do it.” And then telling them, “It’s normal. Anybody experiences it. But it means you haven’t practiced enough, or you haven’t practiced the right way at home. Because, you know, you need to be ten times as good as you practice at home that you would play good in public. V: Makes sense, I think. Because there are probably ten times as more distractions during public performance than you would normally face at home. A: That’s right. V: You’re not imagining that Mr. Bach is listening to you when you’re playing, right? Therefore, you’re not as stressed out. But, when everybody’s listening to you at church, you’re playing differently. You’re thinking differently, actually. And, um, it might feel more relaxing when people are chatting, when they’re not paying attention to you, like during postlude, they’re having conversation after the liturgy with their friends and family, and the organist is just playing, like background music. A: Well, is it easier for you to play that way? For me, it’s harder. It’s harder to concentrate. V: Well, it depends on where you sit. If you’re sitting in front, and you’re seeing all those people, then yes, it’s harder. But if you are in the organ balcony and you hear your own playing very well, then it’s not that distracting. A: Well, but you know, that’s why I don’t like to play in the Cathedral of Vilnius, because during concerts, tourists can still go and leave free. V: Mm hm. A: And sometimes, you play in the middle of recital, and you feel like you are playing in the middle of the market, because you hear, you know, all those feet, you know… V: Shuffling. A: Shuffling. And it’s not a nice thing. At least, I don’t like it. V: Well, yes. I would recommend locking up the door and releasing them only after the last chord has been played. What do you say? A: Well, but maybe then they would start to talk. And what would you do? Would you use duct tape? V: Duct tape, exactly. A: To shut them down? V: You always have great ideas, Ausra. A: Yes, I would go to jail for my ideas! V: I would visit you once a month. No, maybe twice a month if you’re good to me. A: Nice. I appreciate it. V: (Laughs) A: But anyway, it’s a common problem for people like Micky, and like us, that know we are always doing better when we are playing just to ourselves. V: And the way to overcome this is probably easier than it sounds. Just measure your own level of accuracy today and three months from now. Or even one month from now. If you’re playing with less mistakes after 30 days, or maybe after, you know, 12 weeks, then you are making progress and you’re on the right path. If the accuracy hasn’t improved over that time, then you need to change the way you practice probably, right Ausra? A: Yes, because you know, making mistakes in public might be caused by two things. Either you lose your concentration, or there are still some spots in the piece that are more difficult than others. You need to check where are you making those mistakes. V: Mm hm. And the way to increase your concentration and focus is to concentrate on your breathing, as we are frequently suggesting. But do this at home as well, not only in public. Practice concentrating on your breaths, and not breathe with shallow breaths, but take deep breaths. Slowly but deeply, and maybe even rhythmically. Pick up some rhythm, maybe once every two beats, or maybe once a measure or every two measures if it’s a fast tempo. See what works for you, right? That would be my suggestion. A: Very wise. V: Yes, I am very wise. Thank you, Ausra. A: You’re welcome. V: Are you wiser than me? A: Stop doing that. V: What? A: You know what. V: Guys, if you want to keep this silliness going, please send us more questions. We love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice, A: Miracles happen. Would you like to learn Poco Lento in C Minor by Cesar Franck from L'Organiste? I hope you'll enjoy playing this piece yourself from my PDF score. Thanks to Jeremy Owens for his meticulous transcription from the slow motion video. What will you get? PDF score. Basic Level. 1 Page. Let me know how your practice goes. This score is free for Total Organist students. Check it out here

Vidas: Hi guys! This is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 441 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Dan, And he writes: Hi Vidas, I noticed that you’d uploaded to YouTube, a version of Carillon of Westminster by Louis Vierne, where you’re playing it slowly. I know you normally do this, so people can transcribe what you’re doing, and eventually produce a print score with fingering and pedaling. This as well, may help me, as I learn things by ear here, due to being totally blind, and finding Braille music to be tedious, and slow. So along with helping people to transcribe stuff, I’d say what you’re doing with that, is also helpful to me too. Take care. And then I asked Dan this question: What is the easiest way for you to learn music by ear? When you hear entire texture or separate hands and feet? Or even separate voices? And Dan replied, What I usually like is to have separate hands and feet, and then entire texture to work with. That has worked well over the years for me. I’ll then take that and work on its parts separately to start out, then manuals only, then right hand and pedal, left hand and pedal, and then put things together. What do you think, Ausra? First of all, could our videos be helpful to people who cannot see? A: I guess, yes, when you record the music really slowly. I guess this might help. V: And even if it’s faster music, it’s possible to slow down twice, by reducing the speed on YouTube. A: Well yes, but then the key will change. V: By an octave, exactly. Lower an octave. But some players, obviously not on YouTube, but some audio players have the possibility to reduce the speed, but to keep the pitch constant. Like VLS player, I guess, can do that. A: Excellent. I didn’t know about it. V: So what people can do is just download the mp3 file from any of our video, and then play it on the VLC player on their computer, and reduce the speed by keeping the pitch constant, and that way will be possible. I remember playing in one international organ festival in our Curonian peninsula on the Baltic Sea, and this is a resort spot, very wonderful place to visit in the summer especially. And I once played there continuo part on the small chest organ, continuo part from Bach’s cantatas, two cantatas, I think. And I was using original notation for continuo, without any chords spelled out, just numbers above the bass. And I supplied the chords by myself, like improvisation. And it wasn’t easy, so I got this YouTube recording of Bach cantata, and played it through VLC media player, by reducing the speed by half, but the pitch was constant. And it worked for me, you know, to master my chords playing and continuo playing together with orchestra this way at home. A: Excellent. V: For awhile, I didn’t do this all the time. Just maybe a few days. So, technology can be helpful today, even for these sorts of things. And then, you know, Dan says he like to have both, entire texture and separate texture for hands and feet. It’s very natural, I think, it’s like a normal practice procedure for everybody. Right, Ausra? A: True. At least it should be. V: Mm hm. When the piece is difficult, we subdivide the texture into separate voices and play them separately, and then combinations of parts. And that’s what Dan needs, and people who probably cannot see also appreciate as well. And then, of course, when they know the texture well, they are ready to play four part texture, or entire texture, and then in a slow tempo, obviously, at first, but videos can be helpful as well. Because, you see, Braille music is slow and tedious for him. I always thought that, you know, it’s a special system to be used for blind people, but today probably, there are more options and people can choose, and it’s not the fastest way. A: Well, you know, I’m not blind, you know, obviously, but I can understand Dan, why it’s easier for him to listen and then to reproduce, you know, music, than comparing to Braille. Because you know, in Braille, you have to touch things to know what is written. V: Exactly. And you have to have a special printer for that. A: Well, yes, but that’s all the technicalities. But since Dan is a musician, it means you know, he has good pitch. Well-developed pitch. And I think it’s easier for musicians, you know, to learn by ear than by touching things. V: Helmut Walcha, remember Walcha? A: Walcha, the blind German organist and composer, yes. I don’t remember him, but I remember our professor, George Ritchie, talking about him, because he was his teacher. V: In Germany. A: Yes. V: And what did he do? A: Well, he would ask his students to play, you know, one voice of the piece really slowly, and then he would memorize it, and then another voice. And in such a manner, he would learn the entire piece. V: It was before the time of videos, and recordings, probably. Recordings were possible, but not maybe cassette recordings, maybe LP recordings, and that was impossible to record at home by your own equipment, you had to have industrial equipment for that. Or, the help of other people, who would play back a melody to you. Mm hm. Excellent. I wish the technology would be advanced enough that they could grab an audio file and then take it apart into separate tracks or voices. And they could do this with MIDI files. And MIDI file can be created by playing it on the synthesizer connected with your computer. And then you could have entire score, entire texture, and then separate parts, or any combination of parts if you want. A: I guess, you know, since every human being, you know, has a different understanding of the world, because some of us are very visual. Some of us, you know, understand words with our ears. And some understand words with entire body. So I guess, you know, everybody has to choose what is the easier way for them to comprehend, to learn music. V: It would be a good business model for organists who would like to focus and specialize for blind people, blind organists, for resources like that. Who would produce audio files – you don’t need videos for that, just audio – for separate voices, combinations of voices, and entire texture. And there are quite a few blind organists in the world, so that could be a niche and very helpful for people. A: Maybe French are doing that, since we have such a long-lasting tradition of, you know, blind organists. V: If they’re doing some, maybe, they are not doing this on the internet. I haven’t seen this yet. A: Could be. V: Yes. But even if Dan or people who could not see, would just take this audio file or video, and play back in a slow tempo, the entire texture, it’s possible to pick up separate voices, right, and develop your own musicality this way much better. You know, you’re like your own teacher this way. It’s not easy at first, because you have to hear inner voices. But with practice, probably people can develop this. At least, Dan is suggesting, between the lines, that it’s helpful. Right? A: True. V: Okay guys, lots to think about. Please keep sending us your wonderful questions. We love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice, A: Miracles happen. |

DON'T MISS A THING! FREE UPDATES BY EMAIL.Thank you!You have successfully joined our subscriber list.  Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas

Authors

Drs. Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene Organists of Vilnius University , creators of Secrets of Organ Playing. Our Hauptwerk Setup:

Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

This site participates in the Amazon, Thomann and other affiliate programs, the proceeds of which keep it free for anyone to read.

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed