|

Welcome to Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast #95!

Today's guest is a talented young American organist, Christopher Henley. He is native of Talladega, Alabama and serves as the organist of Anniston First United Methodist Church, where he provides service music for the 8:30 and 10:30 traditional worship services, manages the Soli Deo Gloria Concert Series, and accompanies various vocal and instrumental ensembles. Prior to his service at Anniston First, he served as the organist of the First United Methodist Church in Talladega and Pell City, Alabama. He is the founder and artistic director of The Noble Camerata, an auditioned vocal ensemble, that sings choral services in the Anniston, Alabama area and seasonal concerts. In addition to his church responsibilities, he serves on the faculty of the Community Music School of the University of Alabama, where is an instructor of piano. In March 2017, Christopher was named a member of the Class of 2017 “20 Under 30” by The Diapason magazine, an international journal of organ music, for his leadership in the field of organ and choral music. Mr. Henley is currently a senior in pursuit of the Bachelor of Music degree in Organ Performance at The University of Alabama where he studies with Dr. Faythe Freese. His piano teachers have included Mrs. Pamela Thomson, Dr. Edisher Savitski, and Dr. Tayna Gille. He is also a member of the Early Chamber Music Ensemble where he plays harpsichords for various groups. As a collaborative artist, he has joined with clarinetist, Michael Abrams, to form Basilica Duo: a duo performing works for clarinet and organ. He has accompanied various choirs, including the University Singers of The University of Alabama, the Jacksonville State University A cappella choir, and Talladega College Choir. He has also performed with the Alabama Symphonic Band and the Jacksonville State University Trombone Ensemble. Active as a performer, Mr. Henley has performed across the United States as a soloist. Recent performances have taken him to Saint Thomas, Fifth Avenue in New York City; First Plymouth Congregational Church in Lincoln, Nebraska; Fourth Presbyterian Church in Chicago, Illinois; and St. Mark’s Episcopal Church in Berkeley, California. Upcoming performances include appearances in Atlanta, Georgia; Ashland, Alabama; Tuscaloosa, Alabama; Washington, D.C.; New York, New York; Tulsa, Oklahoma, and Portland, Oregon. As a competitor, he received first prize in the 2013 University of Alabama Organ Scholarship Competition, the 2013 Minnie McNeil Carr Organ Scholarship Competition, and the 2012 Clarence Dickenson Organ Festival (Beginner). In 2015, he was a finalist for the Southeast Regional Competition for Young Organists for the American Guild of Organists in Charlotte, North Carolina. Mr. Henley is an active member of the American Guild of Organists and The University of Alabama Music Teachers National Association. In the AGO, he was appointed as a member of the executive board for the AGO Young Organists initiative for the Southeast Region. He also serves as the student affairs coordinator of the Birmingham Chapter. For MTNA, he has served the collegiate chapter of UA in the capacity of secretary. In this conversation Christopher shares his insights about his organ playing experiences as well as about the audience's aspect in creating art, responding to criticism, finding dialogue between fellow musicians and sharing your work with the world. We also talked about the value of blogging for organists. Enjoy and share your comments below. And don't forget to help spread the word about the SOP Podcast by sharing it with your organist friends. Thanks for caring. Listen to the conversation

Comments

By Vidas Pinkevicius (get free updates of new posts here)

Yesterday my student Jay from San Diego, CA asked my help in improving his hymn sight-reading skills. He's 70 years old and occasionally plays as an substitute at church and especially enjoys hymn playing. But right now he's struggling with reading 4 voices from the hymnal. I gave him advice to practice 30 hymns for 30 days from the hymnal while only playing the soprano part. After that he should do the same with the next set of 30 hymns and the alto part. Then comes the tenor part and finally the bass. 4 steps with solo parts, then 6 steps with 2 part combinations, then 4 steps with 3 part combinations and after that he will be ready for the entire 4 part texture. You see where I'm going with this? My 15 step sight-reading system. Do you think this type of approach will lead him to success? By Vidas Pinkevicius (get free updates of new posts here)

I almost forgot I scheduled this organ demonstration today! After the first ear training class this morning for 7th graders, I was ready to go and practice on our school recital hall organ. I wanted to play some Langlais... Without any rush I went to the bathroom to refill my water bottle and then checked out the key from the organ balcony. It was then when somebody called on my cell phone. It turned out to be my colleague music history teacher to whose 6th grader's class I promised to do an organ demonstration. She was teaching them about various musical instruments around this time and pipe organ was next on their study list. So the kids were already waiting for me and I almost forgot this event! OK, it's going to be really fun... I started demonstrating this organ, telling stories about the stops and the mechanics of this instrument. Then I played BWV 565 Toccata without the fugue from memory. I actually forgot the ending so I improvised my own ending (don't tell master Sebastian). I then took out one of the wooden pedal pipes and gave the kids to blow on it. Only after did I understood what kind of mess I made: the pipe was very challenging to put back in place because you couldn't really see the handles on the back side of it. I tried to do it several times, gave up and gave to some of the bravest boys, they gave up and then their teacher volunteered to help out. Luckily she was a tallest one from our group and actually succeeded almost immediately to put the pipe back in place. Then I gave all the kids the chance to play this small 10 stop two manual organ. It has an ugly post-war German really piercing sounding 1' 3 rank Mixture. It turned out to be their favorite stop! Almost all of them used it when they tried out the organ with their hands. While they were playing I took the rest of them into the organ chambers to take a peek and enjoy the "beautiful" sounds from the inside. Heavy duty earphones would've been really nice! Nevertheless they were all extremely happy. Maybe next year somebody from them will take organ lessons... So what's the deal with mixture that fascinated them so much? What do you think? By Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene (get free updates of new posts here)

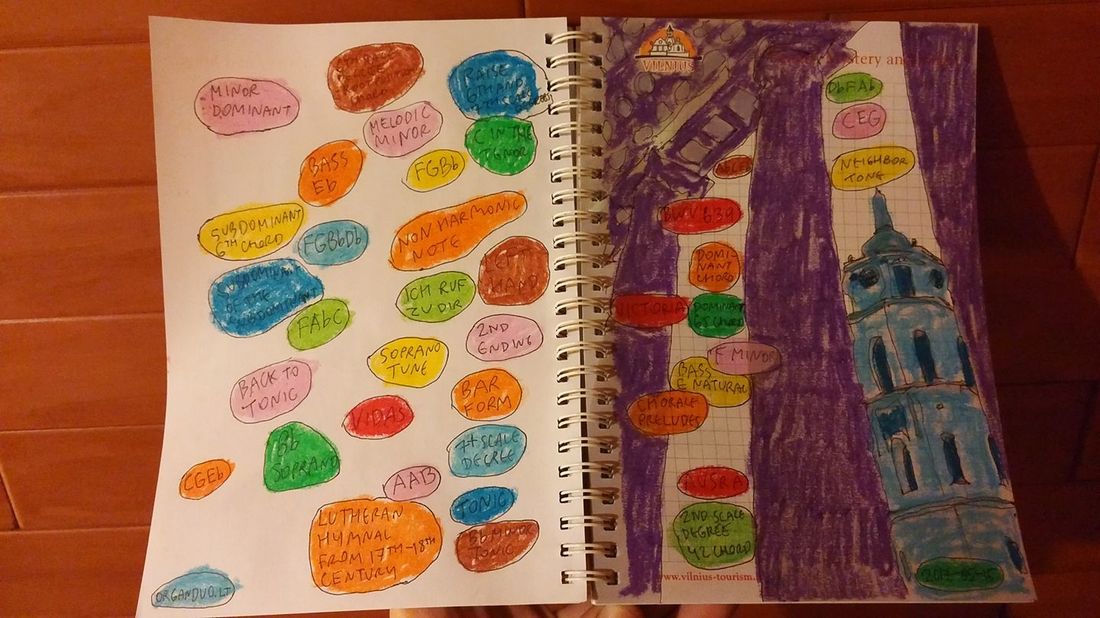

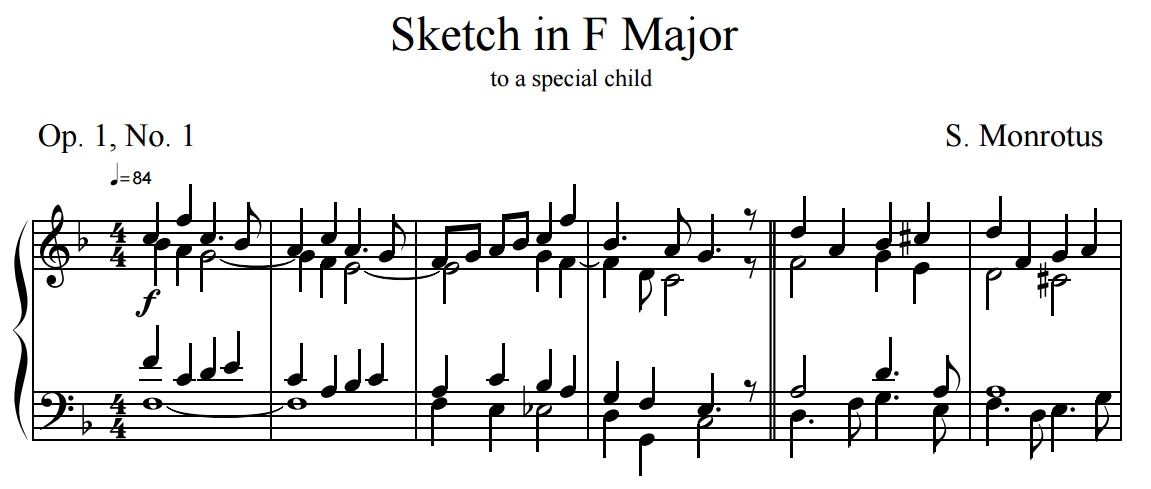

Have you ever noticed a similar structure of many of Lutheran chorale tunes? Usually they have 3 sections: The first and the second are exact repetitions with different text followed by the remaining longer section - based on the thematic material, it looks like AAB form. This is what they call the Bar form. Its origins rest in many German folk songs from the Middle Ages. The two A sections in German are called Stollen and B - Abgesang. The Stollen can have 2 or 3 phrases while the Abgesang is usually about twice as long. Victoria yesterday asked my help for understanding the harmony and structure of the chorale prelude by Bach "Ich ruf zu Dir, Herr Jesu Christ", BWV 639 which comes from his Orgelbuchlein collection. This was a good timing to introduce the concept of the Bar form to her. So when you're playing any other chorale prelude which would be based on the Lutheran melody, try to identify those phrases and sections too. Then you will be thinking strategically how composers did when they created these beautiful pieces. Let me know if you need my help or feel stuck with anything in organ playing. By Vidas Pinkevicius (get free updates of new posts here) My good friend Dr. Steven Monrotus from St Louis, MO asked for my help in critiquing his organ compositions. He is the author behind the blog Organ Bench where he shares his experiences on his path of creating and making music for the King of Instruments. I found his overall writing style quite colorful and solid. He likes to think horizontally and his vocabulary sometimes is based on the methods that Louis Vierne had used. Steve uses online music notation software Noteflight which allows people to compose music without downloading any program to your computer, directly online. For a long time he didn't know how to add a second voice in his scores on the same stave, so he found a way to do it with many dangling ties which really complicated the view for performers too much:  A lot of his works are in 4 part texture so I suggested he take a look at the possibility of adding a second voice with the stems down on each stave. Finally he was able to achieve it using his software. Apparently it wasn't too difficult: The above result is quite professional, isn't it?

If he wanted to send his scores to other organists with the suggestion to perform or to music publishing houses for possible publication, which version do you think would be more likely to receive more positive reaction? Of course the second one. What about you? Have you written some organ music yourself and are looking for help to know how to give your score that professional look which would turn on your potential fans? Check if you use stems down for a second voice, add registration suggestions, dynamic markings, tempo indications and even articulation too. The more precise you are in indicating how your music should be performed, the more chances for good communication you have between you and your audience. By Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene (get free updates of new posts here)

One of the most common mistakes beginner organists make is to keep the uneven tempo in their pieces. Where it's easy, they speed up, where it's difficult, they slow down. No matter how hard they try to keep the steady tempo - it's just too overwhelming. Here's the trick which CONSTANTLY helps me to be precise in my playing: In rhythmically difficult places I keep counting and subdividing the beats down to the smallest rhythmical value of the piece. Let's say, you're playing BWV 554 and some places of this prelude and fugue in D minor are more difficult than others. What beginner organists often do, they slow down in the middle of the fugue where the pedal part comes in. They do this towards the end when the texture gets more complex. Since the smallest rhythmical unit here is the 16th notes I recommend counting in these note values. In your mind keep a steady flow of sixteenths. Then you won't have to worry about uneven tempo. By Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene (get free updates of new posts here)

One of the characteristics of organists who lack musical intuition is that they play only notes without giving any thought about what happened in the mind of the composer when they wrote it. Also they don't think about what any of the notes, passages or chords mean. And I don't mean to give negative criticism here. It's just that they lack certain training which can be improved over time. Usually such organists also tend to end their pieces abruptly. This is like driving your car and when you have finished your trip and arrived at the destination, you simply engage the emergency hand break and your car stops suddenly. The only time we do this is for emergencies, right? So why the ending of organ pieces should be any different? Sure, there are instances when you have to leave your listeners surprised at the end but in most cases they should feel the ending coming. So an obvious way to do it is to gently slow down at the end and hold the last note longer. You have to because as you slow down, you keep counting the beats slower and slower. Imagine, you're playing "Kommst Du nun Jesu vom Himmel herunter" from the 6 Schubler chorale preludes by J.S. Bach and you forget to slow down at the end of the final Ritornello and abruptly release the last note. It's like an accident, right? Instead, keep slowing down in your mind starting maybe a couple of beats in the penultimate measure and hold the last note longer. Do this and your piece will end very naturally. By Vidas Pinkevicius (get free updates of new posts here)

Welcome to Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast #94! Today's guest is Frank Mento who is an American born organist and harpsichordist currently living and working in France. He is Professor Emeritus of Harpsichord at the Conservatory of the 18th precinct in Paris and Organist Emeritus at Saint-Jean de Montmartre Church, also in Paris. He has recently published the 10th volume of the his comprehensive Harpsichord Method. This treatise is especially suitable for organists because harpsichord and organ in early music are very closely related - they are like cousins. Frank wrote this method because he started teaching harpsichord back in 1992 and there was very little material available for beginners. There were few methods that were on the market and some had good ideas but they all started from the standpoint that the beginning pupil already had some basic musical knowledge and some basic keyboard technique. The first two or three pages were easy but afterwards they jumped to difficult things so he had always to add material making photocopies writing in his own exercises to fill these gaps. So Frank ended up by writing his own method to make something coherent and more easily accessible to people who have never heard of harpsichord. Since 1994 this method is being used in 27 countries, covering Europe, North America, South America and Oceania. Frank hopes that he also will get students from Africa in the future. Frank has already been on our podcast talking about his Vol. 8 and now that this project has been completed it will be great to see his complete vision for students who want to learn early keyboard technique. Enjoy and share your comments below. If you like these conversations with the experts from the organ world, please help spread the word about the SOP Podcast by sharing it with your organist friends. Listen to the conversation By Vidas Pinkevicius (get free updates of new posts here)

I've heard people play mechanically like automatons on the organ. They have good technique and can play quite fast but their playing lacks humanity. It's fun to listen to such playing... for about 20 seconds. After that - it's too predictable. What's the secret here? Of course to stress the strong beats. Make them longer. And not necessarily every strong beat in the measure, perhaps only the most critical ones in the sentence or in the musical idea. Then you will sound like a human being and people will be touched by your playing. By Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene (get free updates of new posts here)

Your public organ performance is in 3 weeks and you feel terrible about your playing especially this one piece. What can you do? Should you cancel the event? You could, but your credibility as an organist will suffer because of this. Plus it will get more and more difficult to show up to play in public if you hide from challenges. What you can do is of course quadruple your organ playing efforts during these 3 weeks and analyse this piece from the strategic point of view. Do you make mistakes in every line or is it in just a few spots? Does your beginning and end sound strong? If it does, you can cut your piece and play just the portions which usually go well. Now, this plan is just for an emergency, I don't recommend you do it all the time. But it's better if you still play in public, even if the piece is incomplete. Can connect the episodes of your piece so that they flow naturally into one another? Of course beginning and ending is a must. Don't touch them. But maybe you can cut some of the most difficult spots. Remember, you can modulate certain cadences into keys which work nicely together. Just be a little bit creative and find a sweet spot where the piece without the most challenging middle episodes still would sound convincing. You'll still will be practicing the whole thing. Maybe with 4 times the energy than before. But if things go sideways, you'll know what to do. What do you think? |

DON'T MISS A THING! FREE UPDATES BY EMAIL.Thank you!You have successfully joined our subscriber list.  Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas

Authors

Drs. Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene Organists of Vilnius University , creators of Secrets of Organ Playing. Our Hauptwerk Setup:

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

This site participates in the Amazon, Thomann and other affiliate programs, the proceeds of which keep it free for anyone to read.

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed