|

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start Episode 204 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. This question was sent by Kae, who is helping us to transcribe some of the podcasts into text and make them into blog posts. So, she wrote a question: Labas Vidai ir Aušra! She knows a little Lithuanian. So this means, “Hi Vidas and Ausra!” She continues: I was inspired by AVA192 to make a video of my newest creation--a lyric song, which meant I would have to sing (*shudder*)--and post it on YouTube for the whole world to see! I had a couple thoughts about it that I'll share with you: I try to make my lyrics as non-specific as possible, probably for 2 reasons. 1) I want them to be universally accessible. But 2) I think I also try to hide my personal life, even though songwriting involves putting it on display for the whole world--so I make lyrics that don't give away specific details. It's a weird balance I have to find, isn't it? ...Or do I? Another thing I was thinking about is: I want to encourage people to use and change and improve any music I create. I don't believe in copyrighting the kind of stuff I create, which is mostly keyboard music. What do you think about that? (I arrived at this conclusion after I discovered a beautiful piano concerto by Władysław Żeleński, and the library in Poland that is sitting on the sheet music wouldn't let me even borrow it for my school's concerto competition. Only one or two people have ever recorded it, and I suspect only those people have ever been granted access to copies of the music. How do they expect to honor Żeleński, their own country, or music itself, if they treat it like it's not music and leave it to gather dust behind red tape? No wonder this composer is so obscure! I would be so mad if a library hoarded up my copyrighted music after my death and refused to share it.) And she gives the video link, which you can also click and view: https://youtu.be/x8W8njPFT7Y And she writes further: Thank you for everything you do. The world is really a better place, with people like you. I can't wait to meet you in person this summer! Love, Kae So, Ausra, Kae is coming to Vilnius on the occasion of the song festival we’ll have in July! Thousands or even tens of thousands of singers will come, who have Lithuanian background, at least, from all over the world; and sing at this huge festivity, because this year the entire Baltic States--Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia--celebrate the centennial of their independence! A: Yes, it will be very exciting, and we are looking forward to see Kae in Lithuania. I think we will have a great experience, and I hope she will like it here. V: There is so much to see and enjoy, I think. Each Baltic country has their own singing traditions; and together, we are quite unique in the entire world with these song festivities--massive festivals where thousands of people gather every four years, I think. So wonderful. So, Kae started to compose music... A: Yes, it’s wonderful; I think it’s wonderful. V: And not only compose, which a lot of people do, but she started to share her music. A: Yes. V: Which only a few people do. A: And it’s wonderful that she creates her own texts. V: Right. A: Lyrics... V: Lyrics. A: Because I remember the day when I was back in high school, I loved poetry. V: Uh-huh? A: So I what I would do is, I would pick up some kind of lyrics, and I would sit down at the piano, and would play whatever accompaniment, you know, just based on basic chords; and would sing those poems. And it was fun. I had a great time. V: Did you used to write down those lyrics in your own notebooks? A: Yes. V: Did you keep them? A: Yes, I still have them. There are like, 4 volumes of them! V: Do you look at them now, sometimes? A: No, because you know, actually, I don’t have so much time--and actually because I memorized almost all of them, and I could still recite maybe half of them from memory. V: Wow...You have excellent memory! A: Well...it’s not so good as it was, you know, 20 years ago...But still, still, it’s okay! V: Is it a useful skill, to have good memory? A: Yes, it’s a very useful skill. V: To remember everything? A: But sometimes not, because you would like to forget some things. V: To remember good things, and forget bad things? A: That’s right. V: Excellent. So, back to Kae. She created the lyrics non-specific, right? And generally accessible, to be universal, so that other people could relate to them, right?--not about her own life. In part, also, she wanted to protect her personal life. A: Mhm, yes. V: Right? Because if she puts something on YouTube, then thousands of people might see and hear and comment, and those comments might hurt. (Of course, you’re always free to disable those comments, if you don’t think that they matter. They can vent somewhere else.) A: That’s true. V: But I don’t know...What would you recommend Kae--to create something very personal, like, very very vulnerable, you know--about her own feelings or experiences, or something more universal? A: Well, you could look at two sides to this issue. Because on one hand, I understand why she wants to create more universal lyrics that it would be accessible to everybody and understandable to everybody, and she would not expose herself so much to the public. V: Mhmm. A: And it’s okay. But on the other hand, I think that if you would create more personal things, they might excite other people more… V: Personal? A: Yes, personal. V: Mhmm. Because they understand that you’re being vulnerable. A: And they might--your lyrics might touch their hearts more. V: Exactly. In your experience from reading poetry, do poets sometimes write personal-related poems, or are more of them general, universal? A: Um...they do it both ways. But yes, that poetry which shows the inner feelings excites more. V: Mhm. A: Because, look, we seem like each of us is unique--and yes, each of us is unique--but I think we all share the same feelings; and you know, everybody always has certain good experience and bad experience. You know, many of us experience love, and… V: Mhmm? A: And other things. So… V: In order to protect herself, she could simply publish them under a pseudonym. A: Yes, that would be a great idea. That’s what many poets did in their lifetime. Or writers. V: Of course, if she publishes a video, then her face is visible, right? But she could point the camera away from her face, right? A: Yes, if you would do, like, a profile picture...then you wouldn’t be so well recognized. V: Or maybe just looking at the score, facing the score, so that people will see the score. Or hands. A: True, true, true, yes. Yes. So there is always a way to make it work. V: And I’m looking now at the YouTube channel by Kae, and she has quite a few pieces arranged and performed--from West Side Story...an Estonian folk dance arranged for 2 pianos...right? Even some Polish composer, Leopold Godowsky. This is interesting; I think she could continue. Do you think, Ausra, that YouTube today is the best place to share your creativity, or not? A: Well, it’s a good place to share it, because so many people use it... V: Mhm. A: And you would have a bit larger auditorium. But also, I would share it on Musicoin. V: The audio file? A: Yes. Because you would get back more out of Musicoin, I would say. V: Especially if the platform grows, then the value of that coin grows, too. Then your entire revenue also grows. And put it on Steemit, too, because they have a DSound application which accepts audio files; or the video version of Steemit is DTube. It’s like YouTube, but on the Steemit blockchain. So you get also some revenue out of that when someone uploads your content. A: Yeah, so you have a few options; so do it. V: And it’s only the beginning of blockchain-based social networks and content monetization techniques; so...I’m sure there will be many others, and maybe better platforms to post your content in the future. So always be on the lookout for revolutions in this field, because blockchain is the future, I think, of media, and people should not neglect this, right? Because it directly rewards creators. So...and...Kae doesn’t believe in copyright. Do you believe in copyright, Ausra? A: Yes and no. Because in some cases it gets frustrating, like Kae describes about Władysław Żeleński. V: Mhm. A: But on the other hand, you have to protect your work somehow. V: Mhmm. That’s the thing--now, you can have not public domain music, but a Creative Commons License, which means you are free to share and distribute, and only you have to give credit to the person who created it. But it’s free, right, to do anything you want with it. But the thing with Creative Commons is that you still cannot really monetize it, right? You can’t live off your art. So there has to be some other way to monetize your brain, so to say. And one of those ways is probably blockchain-based, right, that we mentioned earlier. So copyright means that if somebody picks up that you have performed, let’s say, Władysław Żeleński’s concerto--so then, if this is copyrighted, a portion of your revenue will go to the copyright owner of that work. Maybe relatives of Władysław Żeleński. Or...I don’t know if the library has copyright. Probably not. But maybe the publisher has. I don’t know. So, in part, yes: people have to be rewarded for their work; that’s why we have copyright for 50 or 75 years after the composer’s death. But that’s a sometimes tricky situation; because you don’t always know if the person has performed or not--right, Ausra? A: Yes, that’s true. V: But now, blockchain-based platforms for copyrighted content are also being created, so people should check out them soon, also. It’s a new paradigm now, with blockchain--they can automatize everything and make it so easy to check and track, it’s like distributed a digital ledger, where everything you put on that ledger stays forever; and you can’t say, “No, no, I didn’t perform the concerto by Władysław Żeleński!” because the ledger says you did, you know? A: Huh. Yes--no way to hide! V: Mhm, yeah. Excellent. I just would add--I believe that creators should get paid for their work. And in what form or what shape, it depends. A: But yes, you also need to share your work; because otherwise it will just die. V: Exactly. If you hide--if you always protect it under copyright--nobody will notice it. So it’s a balance. Maybe when you are just starting, you could share them more freely; and when you are more advanced and mature, you could start to, I don’t know, hold back a little. A: Yes; that, I think, is a good suggestion. V: Right. And it’s always good to monetize your creativity, and control it--not give away copyright to other entities, like institutions or companies, because they will abuse your rights for sure. A: Yes, that’s true. V: Okay! Thank you guys. Keep creating, keep sharing your music--and not only music, you can do anything you want today. And keep sending us your wonderful questions, we love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice… A: Miracles happen.

Comments

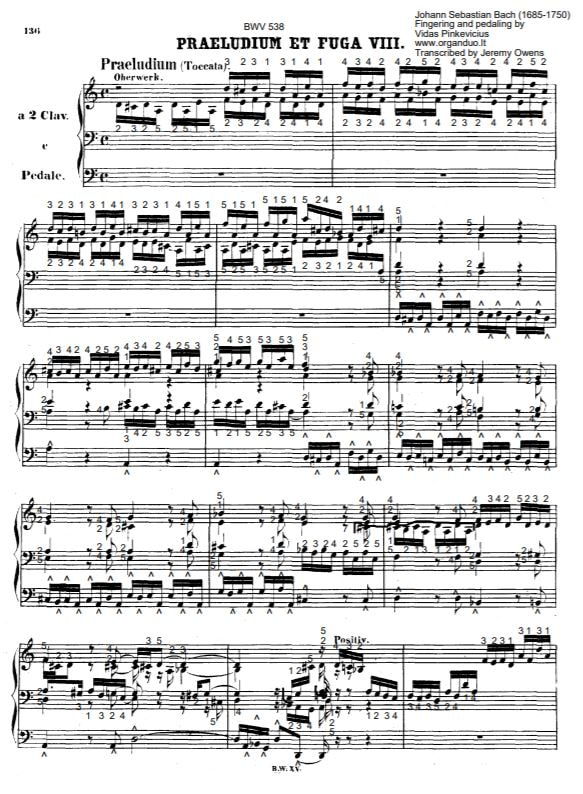

Would you like to master Toccata and Fugue in D Minor, BWV 538 (Dorian) by J.S. Bach?

I have created this score with the hope that it will help my students who love early music to recreate articulate legato style automatically, almost without thinking. Thanks to Jeremy Owens for his meticulous transcription of fingering and pedaling from the slow motion videos. Advanced level. PDF score. 12 pages. 50% discount is valid until April 27. Check it out here This score is free for Total Organist students. Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

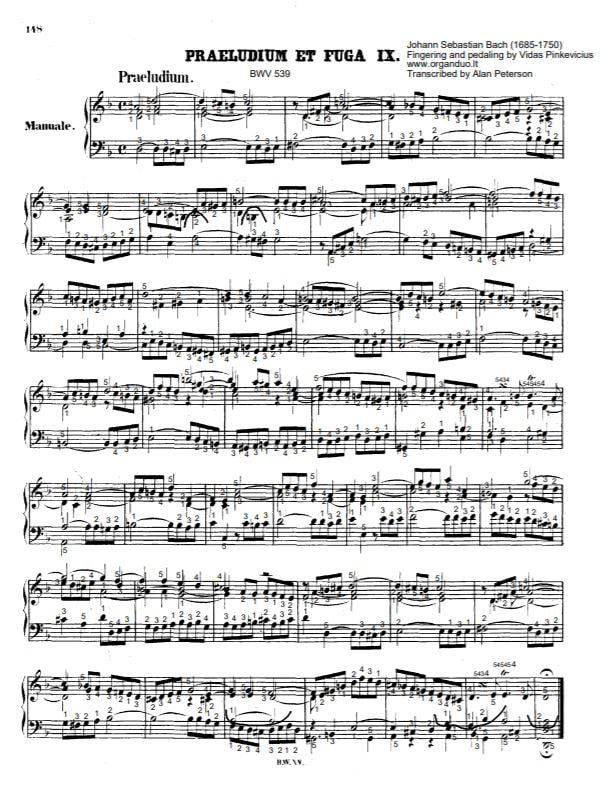

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start Episode 203, of #AskVidasAndAusra Podcast. This question was sent by Robert. And he writes: Hi Vidas ... Robert here again from Vancouver Canada: I'm at a point where I read well and have pretty good independence with hands and pedals. I seem to have trouble with arpeggios though, left and right hand. Basically it's doing the fast transitions to other chords (in the progressions) which are often in inversions. Any material you know of or from your own courses that really exercises a disciplined technique? Cost factor I'm fine with as this is something I'd really like to get " under my fingers " yet, so to speak. I'm just playing this material way to slow. Appreciate your or Ausras input! 😃 Robert V: So Ausra, do you know of any courses or sources for information about learning to play arpeggios? A: I’m sure there are plenty of sources, you know, how to play arpeggios well. But for, in order to do that you even don’t need any additional material. You could just do it on your own. Just pick up any key, for example D Major, and start playing D Major arpeggios. V: But then you need to know the fingers. A: Yes, you need to know fingering. V: And usually the fingering is very naturally understandable if you have some experience with chords. A: Yes. And you know, I’m sure you could find in a library, books that consist not only of arpeggios but basically in order to, you know, build up your technique. As kids at an early age we start to play scales, chords, arpeggios and chromatic scales. V: Mmm, hmm. A; In various manners. And these four things actually help build you, up your technique. V: In addition to etudes, right? A: Yes, yes. V: Mmm, hmm. So one source to look at while waiting for our material—we haven’t prepared such a course yet—but since you are in need now, you could look at Hanon exercises. And in part two, at the end of part two, they have scales and arpeggios you know, keys. So that’s all you need probably, for now. And if, while you are in Hanon collection, check out the previous exercises. In part one too, they are very, very good. The aim for Hanon is it to get perfect technique over time while playing on the keyboards only one hour per day. Because in the fast tempo, you can sight read entire collection—there are three parts—in one hour. I don’t know who can do this because it’s really, really difficult, the third part, I mean, but virtuoso pianists can. A: Sure. So, and for now, if you have trouble, you know getting right arpeggio passage in the piece that you are working on, make an exercise from that particular spot. And check if you are playing with the correct fingering. This is a very important thing. Then you will play it fast. V: What to you mean Ausra, do an exercise based on your piece? A: Well, take a spot that you cannot play well, V: Uh, huh. A: Where you are making mistakes, just a little excerpt of with it. V: Yes. A: And play it many times. Especially in the slow tempo first, check your fingering if it is correct. Then you know, increase the tempo. V: Like one or two measures, right? A: Yes. Like one or two measures. Then you can have fun with it — you can transpose it too. V: Ohhh. A: Into different keys. V: Right! And then, of course by that time you even memorize this fragment. A: Yes, and you know, especially what I do with arpeggios, you have to know on which note to lean. If it’s a short arpeggio then it’s enough to lean in one spot usually at the bottom of the note or on the top of the note, depending in which direction the arpeggio go. But if it’s longer arpeggio, last more than one, one, one measure, then you will do, will have to do another accent somewhere. So that’s what helps me. V: Usually those longer arpeggios are based on one simple chord, like C Major tonic chord, and they just repeat the, the first scale degree one octave higher, two octaves higher, three octaves higher. A: Yes. And even if you know, if you make text mistakes, maybe you don’t know what those chords are, those arpeggiated chords. And this is also a good way you know, to, to play piece better and to feel more secure with it, to know what theoretically what’s going on. V: You mean that playing arpeggios will help you to understand music theory too. A: Yes that’s right. That’s what I mean. V: Prepare for harmonies. A: Yes. V: Nice! Do you think that isolating those measures and playing them over and over again plus transposing them, probably from memory, would help you in improvisation? A: Definitely, yes. V: How? A: Because you would develop sort of muscle memory, by transposing excerpts like this, and at the beginning you might need to think very carefully and slowly about them. But in time, I think you will be able to not think so much about them and do it almost automatically. V: You will develop sort of a bag of tricks, right? A: Sure. V: That you could later use in your own improvisations. That’s of course, that will be in the style of other composers though, right? But that’s in principle the same technique that jazz players are doing. They listen to recordings over and over again and maybe now in the slow tempo and transcribe, the notes. They call them licks, those fragments. And they then memorize, transpose, and later reuse them in their own improvisations. A: Yes, and you know, I think now in the 21st Century, they are too concerned about being original. Because look at the history of, of, of music. You know composers especially at the beginning of their career, they copied each other. They learn from each other. And it wasn’t considered a crime you know, to, to, to copy somebody, or something. V: Mmm, hmm. A: So I think, why not, you know, take something that is good from those times, and do it nowadays, especially when we are talking about improvisation. V: Mmm, hmm. It’s, it's like language, because music is communicating in some form of language, which is not text based but sound based. So if you have a version of language that other composers used, and you like it, there is no crime in, in communicating in this language yourself, right? Or part of that language. First you will shape and adapt that language for your own needs, right, as you develop. Because, because, look, you will not only copy one composer, you will probably mix ten or twenty composers together. Don’t you think Ausra, that this way you will become original? A: Yes. V: This mix of, of ten or twenty. A: Yes, it’s still will sound like you, not like somebody else. V: Mmm, hmm. A: Maybe it will remind of somebody else but, but still it will be your thing. V: Because other people who are doing the same thing, maybe they’re copying other composers in that twenty group. Maybe some of the are the same like you are doing, but not all of them, and the mix would be unique. A: Yes, that’s true. So now going back to the course. First of all, you need to check your fingering, if it’s really comfortable and fitting the particular passage, playing a slow tempo, transpose it to the other key. V: And do it over and over again. A: Yes. V: Excellent! I think this will be helpful to people who want to expand their technique. And their creativity too. A: Yes. V: Thank you guys for listening. This was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: Please send us more of your questions. This is really fun to helping you grow. And remember, when you practice… A: Miracles happen! Would you like to master Prelude and Fugue in D Minor, BWV 539 by J.S. Bach?

I have created this score with the hope that it will help my students who love early music to recreate articulate legato style automatically, almost without thinking. Thanks to Alan Peterson for his meticulous transcription of fingering and pedaling from the slow motion videos. Intermediate level. PDF score. 6 pages. 50% discount is valid until April 25. Check it out here This score is free for Total Organist students. Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start Episode 202 of Ask Vidas and Ausra podcast. This question was sent by Eddie and he wrote: How can an existing church with a wonderful Rieger organ but dry absorbent acoustics be improved either by mechanical means or electronic reverberations systems? Any experience of this? It's in St Georges Anglican Church Parktown Johannesburg. Really a superb two manual organ but the room is quite dead and sec - I imagine early-reflection panels on the side walls and perhaps even in the roof/ceiling (or both) OR otherwise Electronic Reverberation system could be considered! Building is 'n shoe-shaped designs by a famous SA church architect Sir Herbert Baker! V: Ausra, I asked our friend and organ builder Gene Bedient to get a perspective on this and here is what he wrote: “As far as general acoustical suggestions hard surfaces, remove carpet, hard floor, irregular surfaces to diffuse sound efficiently, avoid flimsy wall panels such as thin drywall. Such panels absorb low frequency.” So were not really experts on acoustics, right Ausra? A: Yes, that’s right. V: But Gene probably knows quite a bit more than we because he built many wonderful organs in different acoustical environments throughout his career. And not every church, not every building has reverberant acoustics. A: That’s for sure, yes. V: Especially in the U. S. So in the case of Eddie’s in South Africa situation I think if they could really remove carpet, right, those things? A: Cushions. V: Cushions, exactly. What else? Umm in general avoid any cloth right? A: Yes. V: That would strengthen the reverberation a little bit maybe one second or two seconds. A: But still I don’t think you can do something significant in this kind of situation. V: But then Eddie mentioned he imagines electronic reverberation system could be considered. Imagine that. I don’t have any experience with this. Do you? A: No, I have neither but I wouldn’t do it because it sounds so bizarre. If the organ is pneumatical or mechanical then adding stuff like this you know I don’t think would work. It might make situation even worse. V: And electronic reverberation system solution might be expensive too. A: Yes. V: Because I understand finances are important right here. A: Look at the bright side of this thing you know you can do repertoire that would not work maybe in large acoustics. Do more chamber music, ensemble music. That works quite well you know. And in church like this you know I don’t know if organ is upstairs or downstairs. V: He doesn’t say. A: But then we have no church with large acoustics and we have for example settings the choir has to be downstairs for example or the soloist has to be downstairs and the organist is upstairs you can never you know play together. But if the acoustic is dry you can easily do arrangements like this when soloist or choir sings from downstairs and you play upstairs and it still works quite well. V: And then of course organist has to adjust his articulation. A: Yes, you don’t have to articulate so much you know do a little bit more less space between the notes. So of course you have to play at a faster tempo too. V: For a lot of people it’s easier to play in dry acoustics than in reverberant ones. A: Yes, that’s true. Because it’s more like at piano you know, playing piano that way. V: What you play is what you hear. A: Sure. V: Um-hmm. It seems like it would be quite expensive remodeling of the building if you want to improve acoustics significantly. A: Because I think that acoustics is such a thing you have to think about before building a building. V: I know. A: Unfortunately that not so many architects now considering acoustics in general. Not only in churches but concert halls a well. Like we have this Siemens arena, so called is Vilnius which holds how many people? A big crowd actually. V: Ten thousand,maybe fifteen thousand. A: I think the one in Kaunas holds fifteen thousand people. But this one in Vilnius holds ten thousand people and it’s used for all kinds of different activities for sports, for basketball, and sometimes it holds concerts as well and acoustic is just horrible. V: And Vilnius University is planning to have a special concert next year there with classical music as well so we don’t know what kind of acoustical environment it will be. A: I don’t know about this organ in Johannesburg, maybe some mikes would help if you amplify the organ, I’m not sure you know. You really need to consult a sound engineer. V: And Gene in our correspondence gave a few contacts to Eddie to contact his acquaintances in this area. So maybe Eddie can find some help further. A: True. But you know even if you will be able to make your acoustics better if you will have a good crowd of people coming to the service you might lose that too. Because with each additional person you know coming to the church the acoustic is diminished greatly. V: Remember what’s happening during diploma graduation ceremonies at University of Vilnius where we play. If for example in empty room it’s like five or more seconds of reverberation with full organ but then when three hundred or more people come and pack into the building it’s completely dry. A: Yes, it’s dry and organ sounds much softer than it would be in an empty church. So you need always to keep that in mind. V: Yeah and play louder if you want softer registrations actually. Good. We hope this discussion was at least in part helpful to you but you really need to get some expert advice on this I think. A: So I think the best advice would be for a future generation would be before building a church think about acoustics because that’s what should come first and then just worry about what kind of instrument you will put in that church. V: Um-hmm. A: Building is the most important. V: And then when you play in such environment the beauty is that you can adjust your playing technique everywhere you go in every different acoustical environment. And at first when you just start playing in public and you have tried maybe just a few organs it’s really strange and uncomfortable to change your articulation, right Ausra? A: That’s true. V: Somehow if you are for example taught in a dry acoustical environment and then going to a cathedral then you are playing legato or more or less legato and it’s completely frustrating to adjust right away and vice versa, the opposite is true. If you are used to spacious rooms and good acoustics then going to a concert hall like this would be quite strange. A: So I guess the most important thing is you know to consider all these possibilities and to know what might you know be waiting for you so be ready in advance. V: And when you play listen to what the audience is hearing right? To the echo. A: Sure. V: If it’s even there this echo. Sometimes you don’t have echoes. But still if there is no echo you know it’s a dry room. A: I know and you know it’s a different feeling because I remember playing in the states in several you know churches where basically you hold the last chord and before even you know releasing the keys it seems the sound already disappeared. So acoustic is so dry, it’s not dry dry but it even eats your sound. V: Like black hole. A: I know, it’s a funny feeling. Not a very nice feeling but you get used to it as well. V: Right. So the more you travel the more experience you will have and the less time you will need to adjust I think. A: True. V: But in Eddie’s case I think there isn’t any possibility to do an acoustical environment of the cathedral out of let’s say supermarket acoustic. A: True. V: Maybe a little bit. One or two seconds reverberation that would probably be the best he can hope for. A: That’s actually two seconds, that’s a nice acoustic. I would consider that a nice acoustic just a we had at Grace Lutheran Church in Lincoln, NE. V: Um-hmm. A: It was nice. V: And again it’s nice when you practice alone but when the big festivities in the church full packed with people then this disappears completely. A: Sure. V: What can you do? A: Well you know then peoples voices fill out the church. It works well as well . V: Thanks guys this was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: Please send us more of your questions. We love helping you grow. And remember when you practice… A: Miracles happen. This is Part 3 of our conversation with John Higgins, the organist and mechanical engineer from Australia. Listen to the audio version here. Here are Parts 1 and 2 if you missed them. The sound quality isn’t great but this is the best I could do while cleaning up the audio file.

V: Was it difficult for you to depress the keys? This organ is notorious for its heavy action. ...Or not? J: I can tell you it was a massive relief, when I first sat down and played one note. I was like, “Ahhhh! It’s gonna be okay.” And from that moment I knew it was gonna be okay, because I knew the reputation of the organ, and how heavy it was; and I was quite concerned. For 2 months before I came here, I’d been playing Hanon exercises with full organ at my home church. So, my home church has a mechanical-action organ, and I would say that organ has the heaviest action I’ve played in Australia. And I’d couple the swell to the greats (only 2 manuals) and pull out all the stops--which is quite harsh to listen to, on the ears!--and I’d play Hanon exercises on full organ. And I think that’s what got me through. V: I see. That’s a clever strategy, right Ausra? A: Yes, it is. I think it helped you a lot. V: I would probably use organ couplers on a different organ, but not necessarily all the stops--maybe I would use just the flutes. A: And it still has a different touch. V: Really? A: Yes, even at our St. John’s Church, yes. If you will play that C with the Principal 8’, the keys will be lighter because the air compression is different. J: I especially notice on my home organ, particularly the large 8’ stops are, I think, maybe the towers have more area, so there’s more flow of air into those big open diapason parts, you should really feel the difference between playing like, a Salicional, a string-scaled versus the open diapason. V: And of course, a few weeks before John came here, the organ suffered a little bit of my adjustment. I had to make the springs harder, or stronger, right? On 2 keys in the middle of the first manual--E and F. Did you notice that? J: No. V: Good, because later I relaxed them a little bit; because to play, it’s a very uncomfortable and uneven keyboard. Because the cipher was taking place, and the only thing I could do or could find to do to help the springs make wider, just a little bit. J: Yes. V: And that fixed the problem, at least temporarily. But Ausra was playing there, the E♭ Major Prelude and Fugue by Bach, BWV 552. And she got this organ when the springs were very very tight, at that moment. It wasn’t a good feeling, right Ausra? A: Yes, it was a bad feeling. J: I found that Manual 1--the bottom manual--I found it was quite beautiful to play: I found it was firm but very responsive, and I felt very connected to the sounds. The second manual, which is the swell/closed manual--the keys felt like they had quite a lot of spring; and when you pushed it down, it wasn’t just initial resistance and then it would go easily--you had to push firm right to the bottom. V: Because they have 2 levels of springs, one on the bottom and one on the top. Because they have 2 winches. J: Yes. V: So, stops you control on the LH side are on the upper winches of the second manual, and stops on the RH side are controlled from the windchest on the lower level. So that’s why they’re difficult to depressed. Not a very pleasant manual, actually, to play virtuosic music. What about this third manual? Did you like it, the lightness of the touch? J: Yes. That was. Overall I really enjoyed the experience of playing the organ. V: You said the pedals were easy to depress, right? J: Yes. A: I think that the audience loved your concert. J: Thank you. A: And loved your speech, too. I think you connected very well with them. V: And I translated John’s words to Lithuanian. And later, after the last piece, John came down to bow to the audience, next to the people, and then he talked a little bit with the people. And one person got John’s autograph, right, on his program notes; and a second person gave John...candy, right? A: Chocolate. V: Or a chocolate box. J: Yes. it was very touching. I think there were about 50 people, which is quite a good crowd--that’s quite a large crowd for an organ recital. A: Yes, it is, especially for a Saturday night in Vilnius, when there are so many other attachments and events going on. J: I found I was very humbled and very touched, that even though maybe many of the people didn’t speak English, it was amazing to feel that I could communicate to them in music--that we all speak the same language of the music. And when I came downstairs from the organ loft to the exit of the church, I wanted to shake everyone’s hand to say thank you as I left. And you can tell so much from how people applaud and how they shake your hand. And I felt very honored; it was very special. People appreciated it. And I hope that in some way I could touch them and inspire them. V: Wonderful. So John, what’s next for you? Do you have plans for your next recitals? J: So, I’m very excited that I’ve been asked to play the Nine Lessons and Carols at our church this year before Christmas. V: Uh-huh. J: And that’s the first time I’ve played for a big Christmas service. I’m very very excited about that. And I’d like to learn “In Dulci Jubilo” by Bach as the postlude--I’ll have a grand piece to finish with that’s appropriate for Christmas! And I’m looking forward to studying that piece for the next few months. And I’ve also had a dream for a few years to record my own CD--not really for making money, but so that family and friends can play the CD and enjoy listening to some of the music. And then, if I ever go to other concerts and play, then sometimes people like to buy a souvenir afterwards. V: Ausra, don’t you think that would be a great gift? A: Yes, it would be, yes. I think that would be wonderful. J: So perhaps you could take this opportunity to give me your advice, seeing that you and Ausra have recorded some very special CDs that have then given you an invitation to play overseas--at St. Paul’s Cathedral in the UK, and at Notre Dame in France. V: Yeah. That can be like an audition for you, to collect your best performances in one place, right, and release them in public, for public viewers--either as a gift or for sale. And when you travel, for example, overseas, you could bring the box of CDs with you and sell them afterwards. People who like your concerts are interested in having some of your music, too. J: So do you have some advice for me--how would you prepare for CD recording, and what things happened that you learned during your recording that is quite different from playing a recital? V: Well, that’s probably a topic for the next conversation, right John? J: Yes. V: Because we are now arriving at the town of Trakai, about 30 km southwest of Vilnius, where there’s a medieval castle from the 15th century, right Ausra? A: Fourteenth. V: Fourteenth century, actually. So this was one of the historical capitals of Lithuania, right? A: That’s right. V: There have been 3: Kaunas, Trakai, and Kernavė. And it’s also a tourist visiting site, because it’s a beautiful lake surrounding the island of the castle, and it also has a very old Baroque church, where we’re going now to find a place to part. Even if it’s on Sunday, there are lots of people. Even though it’s in early spring, visitors are starting to come and enjoy the medieval culture. By the way, before we end this conversation, John, what do you think about Lithuania so far? J: There’s a sense of history here that is very touching; and things that I’ve never seen before; and very different and beautiful architecture. And I appreciate how many people speak English--that has helped me out a lot. And it’s a lovely country. V: Well exactly. People can be friendly here, sometimes not so friendly, right? It depends on whom you approach. In front of us, we’re approaching this church--a very old church, right? I think it’s sort of Baroque. And now we need to park somewhere. So thank you guys for listening, we hope this was useful to you, right? This was Vidas. A: And Ausra. J: And John! V: And remember, when you practice… A: Miracles happen... J: ...And you might end up playing a recital in Australia! [This is the 2nd part of our conversation with John Higgins, organist and mechanical engineer from Australia who came to Vilnius to play a recital at Vilnius University St John’s church. Listen to the audio version here. Here is Part 1 if you missed it. The sound quality isn’t great but this is the best I could do while cleaning up the audio file.]

Vidas: Can you remind us, how many years have you been improvising? Two or more years? John: Probably three. V: Three. And you been playing the organ for seven years, right? J: Yes. V: So, we can quite safely say that you are a seventh grader when it comes to playing the repertoire, and only the third grader when it comes to improvising, right? So that’s, that’s normal if you feel more insecure when you are improvising or more nervous because you haven’t spent, you know, that much time while playing your own creations. And it’s normal to prepare, you know, diligently, music that you improvised almost to the point of memorization sometimes. We all did that with the beginning, and in it’s initial level, and after that you kind of want to break free and create on the spot. But that’s the next level, I think. Right Ausra and John? Ausra: Yes, I think so. J: I would say that when I play the improvisation at time, I would say I’m less nervous playing them then playing pieces because I feel in control and it’s my own creation so it’s familiar to me. To be honest, I was a little bit disappointed in my improvisation on ‘A Mighty Fortress is Our God’ because there is one part I played the chorale theme with double pedals to the melody on the pedals with both feet playing parallel octaves and I had that mastered very well on organs with radiating concave pedal boards so it’s very comfortable with that. But this is the first organ I’ve ever played with a flat straight or flat parallel pedals, and particularly on the edges of the pedal board the spacing between the pedals was so much bigger than I’m used to and I played, I felt like I played poorly with my pedal work. That’s I think partly because of the limited preparation. A: I think you did a great job. It’s unbelievable that you could only rehearse for one day on this organ and your recital was right after such a long flight. V: Because normally people who come from abroad to play at St. John’s, they come on maybe Thursday evening and spend the whole Friday and Saturday rehearsing. So maybe they can get four rehearsals total, two-three hours each, you know. That would be plenty. But for you it would be more like four hours total. And considering that you are still learning you have to play many, many organs and only prepare for this recital in your mind, right? Both having registration and stop layout. I think you did better than could be expected. Right Ausra? A: Yes. And you know, yesterday during recital I thought that John is sort of a living example of someone who’s doing those things that we are talking so often about on our podcast that they actually work, if you apply in your practice, mental preparation. When you have no access to a real instrument or when you travel. And John told us yesterday that he practiced mentally at the airport while waiting for the plane to go to Vilnius. And it’s just amazing. J: An experience that helped me was, in late, late last, no it was early this year, January 2018. A very good friend of mine who has other friends in the organist world gave me a wonderful opportunity to come and try out the organ at the Melbourne Town hall, which is one of the largest park organs in Australia — four manuals, and I think nearly nearly 130 stops, and also the Saint Paul’s Cathedral in Melbourne. A beautiful organ there, four manuals and about fifty stops, fifty or sixty stops. And there was nobody else at the Melbourne Town Hall, just me and my friend. And I played through quite a few pieces that I played in my recital. And afterwards my friend said to me, ‘I’m surprised how well you picked such good stop selection and it sounded so great and balanced, even though you never played this instrument before’. And I told him that I downloaded the stop list off the internet and spent quite a few hours of time in the kitchen studying the stop list and thinking, ‘what stops should I use, to get different sounds?’. And that experience in January prepared me for this and helped me to go to a more professional level that as you saw I had, had two or three different stop options, so suggested the organ. V: Yeah. J: Maybe you could tell our listeners about what I showed you. V: John had prepared a list of registration changes on separate sheets of paper, like five sheets of paper—full stop lists and full stop combinations written out. And I just had to check, right? Double check if they work. And to my amazement, they almost all work without any additional identification with some exceptions right, that I added some spices hidden there, but Ausra, didn’t now that until this morning, right, Ausra? A: Yes. A: I thought that you did all that. V: No, it was almost all John’s work. J: So what I did; I spent many hours in the evenings. I think I watched nearly all of, all of the videos that Vidas has put online, and I watched what manual he was playing on the St. Johns organ, and I had the stop list in front of me and I tried to guess what stops he pulled out. V: That’s right. J: And some of them, when you did the organ demonstration to the German tourists, V: Uh, huh. J: You were telling them longer to play flutes, and I saw, look at the stop list go, what flutes were on this manual and I tried to guess which ones you used and I thought I like how this sounds, or maybe I’ll try something different and then that is how I worked out my stop list. V: You did excellent detective work, right? Excellent. So your research actually paid off, and your hard work of mental preparation and doing everything in advance, made your rehearsals much more efficient, right? J: Yes. I knew that there would be so little times to practice. I remember one of the earlier recitals I played at my home town of Victor Harbor; I, I just turned up at the church, no preparation, and I spent maybe four hours just going through registrations, V: Uh, huh. J: And I was so exhausted that when it came to play the recital in the evening, it was not good at all. And that was a very valuable lesson I learned that if you spend too, if I spend too long rehearsing in the morning before I play in the evening I’m mentally exhausted and, and couldn’t concentrate, so I knew that I had to have most of the work of the registrations done so I could just play the pieces and get used to the organ and then take some time to relax. V: Right! Ausra, how do you usually prepare for instruments like that, in advance or on the spot? A: Actually I like to prepare in advance as much as possible. (Not understandable). V: That’s life saving lesson right? A: Yes. V: That John learned the hard way. J: Yes. V: Excellent! What was the most frustrating thing yesterday for you when you played, or when you were preparing? J: I was disappointed that I couldn’t adjust pedal to the pedal board. V: Mmm. J: But I, I don’t know why it always irritates more than anything when I make mistakes in the pedal. I always like to try play the pedals well and I shouldn’t focus on the negative; just focus on the positive. The pedal solo for the Bach’s Prelude and Fugue in G Major, BWV 557. V: It was good! J: I Was very, very happy that went, that went well, because it was in the middle of the pedal board. V: Yeah. J: But some of the notes on the edges of the pedal board, the low C, felt like I was putting my foot off the edges of the pedals and onto the timbers that supports the pedal board. It felt like a B Natural below the C. V: They have a radiating layout. Good. [This conversation continues in tomorrow’s episode. Stay tuned.] [I apologize for the background noise and recording quality but this is the best I could do when cleaning up the audio. You can listen to the audio version here or read the script bellow.]

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas. Ausra: And Ausra. John: And John. V: Wonderful. We’re sitting in the car and going on our way to the historical medieval town of Trakai to see the castle and John Higgins is visiting us from Australia because just yesterday he played a fantastic recital at Vilnius University St. John’s Church and we decided to spend this time in the car while chatting and recording our podcast conversation so that guys you could listen to our thoughts and ideas. So first of all John, how do you feel? Are you exhausted after your recital? Tell us everything. J: It’s been an amazing experience coming to Lithuania. It’s my first time overseas. It’s a beautiful country. It’s tremendous sense of culture history here. My travel schedule has been very intense and exhausting but for me this is a dream come true. And as I said in the recital Bach walked 200 kilometers from Arnstadt to Lübeck in his pilgrimage to hear the great Buxtehude play and this is a modern day equivalent of that pilgrimage. It think it’s about 18,000 kilometer flight from Australia to here. V: That’s about right John and what do you think about John’s efforts yesterday Ausra? A: I think he was you know amazing. I just could not believe you know that a man in seven years could reach such a level of organ playing. V: We have to remind our listeners that John is originally an engineer, right? He describes himself as a machine doctor because he can diagnose problems and propose solutions for technology for major machinery in plants, right? So, tell us a little bit about yourself, what kind of work you do John. J: So, at the moment I work in a coal mine and that coal mine supplies the coal to a power station. It’s one of the biggest power stations in Victoria and provides about thirty percent of the electricity for the whole state and my job is we work in a department called Condition Monitoring which is to make sure that the machines are in good condition so just like you go to the doctor and have a blood test in the machines we take a little sample of the oil and we can check the different types of metals that are in the oil that tell us what parts are wearing out. We can take vibration readings that tell us the bearings are getting too old or the gears are worn out and we use that to decide when to do maintenance next before it breaks. V: Sounds really fascinating and complicated at the same time. Like reading blood tests, blood test results. Do you announce those results to the machines later on? How do you communicate? J: People will think it’s strange but the machines do have personalities a little bit. You can have ten machines that are the same but have different trends. V: Uh-huh. Oh no, my cholesterol is up. Oh you know… More vegetables. John said. J: That’s right. V: Right. So, I think common in our organ playing world that a person from different professions right? Would stop to play the organ. But in general to play recitals, it’s quite unique, right? Maybe a person like you could learn more than for fun, right? Or maybe at a level suitable for church, maybe hymn playing a little bit. Or to travel the world and play the largest pipe organ in Lithuania it’s quite rare. We have a lot of students but you are the first student who played a full length recital with not very easy pieces and I can say that you did really amazing work, John. J: Thank you so much. A: I couldn’t agree more. I was so proud of you you know listening to your playing. V: Could you remind us what you played yesterday? A little bit. J: Yes, so in tribute to Bach’s pilgrimage I wanted to play four pieces, Toccata in D Minor, Prelude and Fugue in F Major from the Short Eight Prelude and Fugues collection, and “Ich ruf zu Dir, Herr Jesu Christ”, BWV 639 chorale and Prelude and Fugue in G Major, that was the first packet of pieces that I played three pieces for Easter seeing as it was only last week. And I played “O Savior of the World” by Sir John Goss, he was a very famous english composer and organist at St. Paul’s Cathedral. And then “God So Loved the World” which is an excerpt from “The Crucifixion” by Sir John Stainer. A very famous choral work for that time of year. And then I played my own improvisation on Judas Maccabeus theme which is the hymn tune “Thine be the Glory” by George Frideric Handel. Then the next packet I played, I think I played “Nimrod” from the “Enigma Variations” and “Priere a Notre-Dame” by Boellmann from “Suite Gothique.” And “Largo” from “Xerxes” by Handel. And then concluded with my improvisation of “A Mighty Fortress is Our God” to celebrate 500 years since the Reformation. And a short piece called “Waltzing Matilda” a famous Australian folk song, the final piece was “Festive Trumpet Tune” by David Germann. V: Ausra what do you think about this program selection? Was it well suited for this organ? A: I think so yes. Definitely, it was quite well suited. He had such a wide variety of pieces and I was especially astonished by John’s improvisations and thought his playing was so great. Not every professional organist improvises and this is a very rare gift. V: How did you feel about improvisation, John? Were you more nervous than the rest of the program or the opposite, more relaxed? J: If you told me seven years ago when I started that I would play two improvisations in a recital I would have said you were joking, that it was impossible and I would never have started improvising if it wasn’t for you Vidas. I would say that when I play these improvisations in many ways they are rehearsed. So, that was maybe the first breakthrough for me was that I had an impression that improvisation was just sitting there and some daydream from heaven comes and you play this amazing music. But I think my breakthrough was when you taught me that the great improvisers spent so much time studying and preparing for their improvisations and in some respects I’d say that what I try to do was I experiment with things and then I had little segments that I’d memorize and I’d just put them together and see if it sounds OK. The improvisation on “God Be the Glory” I’d been doing something similar to that for maybe two years so it evolves and the improvisation on “A Mighty Fortress is Our God” I only conceived that in probably September of last year in preparation for the major recital that I played to celebrate 20 years since the restoration of the organ in St. Andrews Presbyterian Church in Morwell where I’m the organist. [Our conversation continues in the next podcast episode. Stay tuned...] Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. Vidas: Let’s start Episode 198 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. And today’s question was sent by Austin, and he writes: I am just with 4 years of experience but I have only played mainly four part hymns and Handel works. Currently I transcribed Handel's Dettingen Te Deum into solfa notation for my choir and am just learning the organ part because that's the book we wish to perform this year. After that, safe learning pieces such as For unto us, O thou that tallest, And the gloria all by Handel. I want to study Bach works, most especially the ones without pedal part because over here pipe organ is not easily accessible. I have an organ tutor but no way of practicing from it. So I need your advice on how to go about it. Over here Bach works are not popularly studied it's just mainly Handel, few Mozarts, Henry Purcell etc., most especially chorus works. Interesting situation, Ausra. A: Yes. V: That Handel is more popular than Bach! A: Sounds like English tradition to me. V: Hmm, could be, could be. Especially choir tradition, right? A: Yes. And Handel also worked in England almost all his life. V: Mhmm. So he probably struggles with finding a way of practicing from an organ tutor--from a method book. A: Yes, and also finding an organ with a pedal, as I understood, too. V: I see. Hmm...If you didn’t have pedals, Ausra, in your situation at church, let’s say, right? What would you do? Would you just play on the piano keyboard, or something else? A: Well, yes, I would play on the piano keyboard. But maybe I would just draw myself a pedalboard, and practice imaginary pedals. V: Mhm. A: It depends on the situation in life; for everybody it’s different. But in that case, I probably would just select manual pieces. V: Yeah. For now, like chorale partitas by maybe Pachelbel, maybe Krebs, right? A: Yes, there are many collections of wonderful keyboard music without pedal. All the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book, 2 volumes of it. That collection doesn’t have any pedals. Most of the pieces by Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck have no pedals--most of them, not all. V: Mhm. You know, people seem to hesitate to practice on paper pedals, right? It’s very easy: you just print out a few sheets with real-size pedals printed on them, and then you cut out the borders, right? And then glue those sheets together with tape. And then you have an imaginary pedalboard, as Ausra said. And then you can put it on the floor next to the keyboard that you’re playing. Or if you don’t have a keyboard, you could just work on the table. A: But as I understood, you know, Austin has a keyboard, but it doesn’t have pedal. V: And people who don’t use this paper method say that they don’t know if they’re hitting the right pedals, if they’re not making mistakes right? Because those pedals are not sounding. To which I would reply: it doesn’t matter. What matters is your effort; what matters is your muscle movement. A: Yes, because your coordination still works that way. V: Mhm. A: If you are playing that, then when you get to the real instrument, you will see that it’s not as hard as you thought it would be. V: Because you still will hit approximate distances, you know? If you’re hitting middle C, you will not be hitting some middle G, you know--tenor G, a fifth higher. Because you will have a feeling where this middle C is. So maybe you will hit B or D next to it, but it’s still very close, right? So...We did an experiment, I think at the beginning of our Unda Maris studio. In the first lessons there were maybe 10 people in the rehearsal, and only 1 organ; so I brought paper pedals and paper manuals, and we put them in the balcony. And I think 1 person played the organ, and everybody else played the same exercise together in the same rhythm. And I was conducting those 10 people, I think, like a choir. But only 1 person made a sound. And everybody else played on the paper. And then, after a few rounds of playing that exercise, I asked a random person who had never ever played a real organ before to play this particular exercise with pedals on the real organ! Guess what happened, Ausra? A: He could do it? V: She could do it! (It was our friend Erika.) And she almost didn’t make a mistake! Maybe once. But it was like a miracle, right? A: Yes. So this is a good way to practice, if you don’t have a real organ and a real pedal. V: Exactly. A: Because you never know when the situation in your life will change. Maybe you will get access to a real instrument. V: Of course. This is a temporary solution. Or maybe when you are traveling, right? Never skip an organ practice just because you don’t have access to an instrument. Carry those simple sheets with you all the time, and you can adjust to the situation. Or, if you don’t have paper pedals, you can still pound those imaginary pedals with your feet on the floor, right? A: True. V: In approximate spaces. Then you can have inner hearing how the piece is sounding. Maybe you could improve your pitch this way. A: Yes. V: Could a person like Austin sing the bass part? A: Yes, this is a solution, too. V: Mhm. A: And a good one. V: Remember, we lived in the summer cottage for a few months, and we didn’t have pedals at all... A: Mhm. V: Just the piano. So, my voice is low, and I would play the piano parts--the manual parts--on the piano; and I would sing the bass part and play with my feet on the floor. That’s it. That’s how I prepared for many recitals! A: True. V: Excellent. How else could we inspire people today? ...He wrote that he transcribed Handel’s “Dettingen Te Deum.” That’s very nice practice, transcribing choral and orchestral works, don’t you think, Ausra? A: Yes, it is. V: Yeah, especially if you have a choir, right? If you have a group of people who would be interested in singing it. Sometimes you have to adjust the scoring, maybe if you have 2 voices--maybe women’s voices and the men’s parts--maybe you could then select soprano and the bass only. A: Yes. V: From the given score. What if you have only 1 voice, Ausra? What would you do then? I mean a single-voice choir where everybody sings just 1 line--cannot hold separate voice parts. A: Well, then, you could just write out an accompaniment, in 4-voice harmony. V: Mhmm, based on that original. A: Yes. V: And people could probably sing soprano line most of the time. A: Yes, yes, definitely. V: Whatever’s the melody. A: Sure. That way the piece would be the most recognizable. V: What about if you have a 3-part choir? What would you do? A: Well, I think it would work well. V: Without which part? Tenor or alto? A: Well...good question. You could do either way. V: Or you could adjust the middle voice so that you sometimes play alto and sometimes tenor, depending on whether or not the chord is complete. A: Yes. V: What do you mean, the chord is complete? What does it take to make a chord complete? A: You have to have the root… V: Yes, like in C Major, C. A: Yes. And if it’s a triad chord, you have to have E and G, and then C repeated. V: Right. So at least 3 notes should be sounding. A: Sure. But you could do either C, E--if you have only 3 voices--you could do either C, E, G, or C, E, C, and omit G. V: Omit the fifth. A: Yes. V: Because the third is what matters. A: Yes, what matters. Because the third from the bass shows us if it’s a major or a minor chord. And this is the most important. V: Good idea. I hope Austin and other people can apply that in their practice, and their transcriptions, and make the life of their choir more interesting! A: Yes. V: They will appreciate their efforts, for sure. Thank you so much, guys, for listening and applying our tips in your practice. We love helping you grow, so please send us more of your questions. This was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: And remember, when you practice… A: Miracles happen. Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start Episode 197, of #AskVidasAndAusra Podcast. This question was sent by Irineo. And he writes: Thank you very much maestro, it was a delight hearing that sweet/inspiring organ work. V: I think, Ausra, he wrote me back after listening to some of our pieces we played for Bach’s birthday recital. A: I see. V: It might have been Bach Passacaglia, or maybe your E Flat Major Fugue. A: If it’s maestro then it’s not E Flat Major. V: Exactly, he would write Maestra if it’s about you. Okay. So then he writes: Well about my organ playing, I regret to inform you it's been in the backburner for ages by now because of lack of interest down here and besides things have become real tough for almost everybody. But I still write a few bars every now and then (about the lyrics of my piece, which I intend to eventually upload). Keep up the splendid work and thank you again! Very truly yours, Irineo. V: So, I think he’s struggling with sitting down on the organ bench. A: Yes. V: Because he loves to listen to our conversations or to read about our discussions, um, or to listen to the pieces that we play, but, but then his practice, as he writes, is delayed, postponed. Because, because, lack of interest down here, down where he lives probably, right? A: Yes. V: Uh-huh. So maybe he has a situation where he would love to practice but since realistically he cannot apply his practice to real live situation, you know like public, playing in public those pieces that he played at home. Then he doesn’t feel so motivated to play at home at all. A: Could be. V: What would you recommend, Ausra? Stop playing or find some inner source of motivation? A: Well if it’s really important for you, if you really love organ then you must, you know, keep playing and doing what you are doing. I wouldn’t say that in Lithuania that we have such a wonderful situation for organists. That you know, we have big crowds during organ recitals, or you know, very high levels, general level of you know, church music. I would think quite an opposite but it doesn’t stop us from you know, doing what we’re doing. V: For example, our colleagues don’t come to our recitals at all. A: Never ever. V: Yeah. A: It would be a miracle. V: With a few exceptions, right? A: Yes, yes. V: Mmm, hmm. Our maybe closest friends, but,,, A: Even then you play something new and something really excited and something that is rarely played. And maybe this is the one time, live opportunity to hear such a piece performed live. You know, it seems like nobody cares. V: Exactly. A: And many graduates of organ studies in Lithuania, we stop playing at all. And that’s it. Some of them work at churches but not many of them. V: And those who do work at churches, only minority of them play what they learned at school. A: Yes. Not new repertoire. V: Yeah, make themselves better. A: And then you know, perform. V: They just get by, because yes, it is very un-motivating to work in those situations because the church leadership doesn’t care if you play something new or not, if you play just a hymn or not. A: Yes, if you are mediocre performer, performer or you now, or you perform well. So,,, V: But we are artists, right? And artists, you know, make out, regardless if anybody is paying attention or not, right Ausra? A: Yes, that’s true. V: So the process is important; result is out of our hands, maybe. Yes we could strive to put our art out there, out to the world, right. That’s how we live too. Not too many people in Lithuania share their process, share their art. Be we decided to, not to hide it, right, under the table. A: Yes. V: That’s how Irineo could behave too. It doesn’t mean that he has to you know, limit himself with his own Parrish or his own town when nobody is paying attention. But you never know. Maybe, maybe people around the world will become interested or find something useful. And he writes that he is interested in completing his song and uploading it on the internet. And that could be a great opportunity, right Ausra, to compose more pieces, more regularly. A: That’s true, yes. V: To keep up this practice. Because we learn and we grow and we learn again. A: That’s true. Do you think that it’s very important for people that you know, somebody would notice you, and would say to you, to encourage you to keep doing what you are doing? V: I think everyone needs attention. I haven’t met a person who doesn’t need attention. Even my dad who said ‘oh no, I don’t want to do any self-promotion’, and he painted for decades you know, without maybe anybody noticing him too much. But he would still very happy if, you know, people came to his exhibitions or people came visiting to his workshop. A: Yes, that’s true. V: That’s, I think natural, normal and nothing to be ashamed of. And those who say that, you know, no, I am so self-motivated and I don’t care if anyone is listening to me play, or something like that, then they just hiding something, right? They are acting. They have a mask maybe. And actually, they crave for attention but in another way. A: So do you think it would be a good idea for Irineo maybe you know, to start draw more attention to the organ, in the place where he lives? V: Oh, that would be very natural. He could become a center of attention in his town. Yeah, he would become, like, like number one place to go for people who are interested in something new and you know, unexplored. He would become his own category because nobody will be doing this and then he will not have any competition. A: And would you think that this attention, would, you know, motivate him to practice more, and to improve his organ skills? V: Absolutely! He will see that other people are depending on him to show up, to, to speak, to talk, to, to present, to, to play, to demonstrate. So I think the least he could do is to go to local church and to go to local school and meet music teachers if there are any. And say that he could invite those kids to the organ loft and arrange an organ tour, and play an organ demonstration for half an hour, and then answer kids questions, and let them play with, with a few fingers or even with their feet. That would be unforgettable experience for everybody. A: Yes. I think that’s an excellent idea. V: And if he would do that regularly, you know, like once a month, if for different kids, groups, then little by little he would become a ‘go to’ person in his town, in his area. And of course, Ausra, would you recommend him recording his own demonstrations and uploading to Youtube, or Musicoin or other places online, like, like DSound? A: Sure. That way he would get even more attention, and more listeners, and more interest in the organ. V: Mmm, hmm. And those places also pay you for your music, so he could earn some additional revenue while sharing his work. A: True. V: Wonderful! Thank you guys for listening. We hope you understand how important it is to self-motivate yourself. And if nobody really cares about you, your art, then you make them care by finding other avenues. Uh huh. Not forcing them, but inviting them gently to go to an adventure together with you. And kids and children are most, most eager to learn new things, most curious. A: Yes, because those, you know, childhood impressions, they are so important. And maybe some of those kids will become an organist too. And you will be the reason why he or she decides to become an organist. Wouldn’t that be great! V: Wonderful. Thank you guys for, for listening, for applying our tips in your practice, and for sending us those beautiful questions. They’re really thought provoking, and we hope they are useful to you. This was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: And remember, when you practice… A: Miracles happen! |

DON'T MISS A THING! FREE UPDATES BY EMAIL.Thank you!You have successfully joined our subscriber list.  Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas

Authors

Drs. Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene Organists of Vilnius University , creators of Secrets of Organ Playing. Our Hauptwerk Setup:

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

This site participates in the Amazon, Thomann and other affiliate programs, the proceeds of which keep it free for anyone to read.

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed