|

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 159 of Ask Vidas and Ausra podcast. This question was sent in by Monte and he asks about organ Sight-reading Master Course. Vidas, Toward the end of days 5, 6 and 7 of week 1 in Organ Sight-Reading Master Course a second voice sneaks in. Is this meant to be added to the right hand playing up to that point, or does the left hand participate ? Thanks. Monty (this course should culminate in something like the award of a Master's Degree in Counting!) V: This course should culminate in something like the award of a Masters Degree in counting. Ausra this is the course based on the Art of the Fugue by Bach. I remember creating this course a number of years ago with the hope to help people to enhance their sight-reading skills. Especially in early sight-reading skills. So, or course this is a very simple solution, right? The course is structured that you have all the fugues or counterpoints specifically for one hand and then for another hand. I think Monte should play with just the right hand in that case, right? A: Fantastic also. V: Because just adding one additional note just for the left hand doesn’t make sense at this point. A: That’s true. V: Because later, in a few weeks when two-voice structure will come in. Maybe then he will need to use both hands. A: Yes, that’s true but you know with the Art of the Fugue I have thoughts. Quite a few performances you know actually on organ and harpsichord as well. So in terms of which hand needs to play what it is questionable. It’s a good question for discussion. Because you would do it one way if you are playing it on the organ and another way if you are playing on the harpsichord. What do you think about it? V: You are right because with the organ you could add the pedal line. A: Sure and I think those who perform that fugue on the organ definitely play it with the pedal. V: But not every fugue is done with the pedal. It’s not possible to play those canons for two voices with the pedal. A: Yes, because I don’t think you would have enough space in the pedal part. V: It goes too high. In general, Ausra, is it a good exercise to try to sight-read one line at a time of such polyphonic pieces from the Art of the Fugue? A: Yes, I think it is a good way. V: I made this course a little bit easier than I practiced myself because originally I practiced Art of Fugue with the intent of mastering clef reading, not only sight-reading because originally it is written in four different clefs. Soprano clef for the soprano voice, alto clef for the alto voice, tenor clef for the tenor voice and bass clef for the bass voice. The bass clef is the most familiar for everybody, right? And there is no treble clef here right? A: Yes. V: So, instead of playing with the treble clef, originally it was written for the soprano clef. We have remind how does it read, right? A: Yes, soprano clef is on the first bottom line of the staff. V: Which note? A: In the treble clef it would be E on that line. But the soprano clef always marks the C note. V: On the first line. A: Yes, on the bottom line. V: And the second voice, alto clef has also C clef but on the middle line, on the third line. A: Yes. V: What about the tenor line? A: Tenor line is on the fourth line. V: C note is on the fourth. A: Yes. Because in general all these clefs they always mark the note C of the first octave. V: Do you think people would have practiced these scores more eagerly using original C clefs or with simple today’s treble and bass clefs? A: Well you know, knowing how my students at school don’t like to sing solfege exercises for the C clef and those have only two voices I believe only a few would love to practice using those clefs. V: Too few. A: Yes, too few. V: Too few people are like me. A: Well you know it is hard for your brain. Not everybody could comprehend it. V: Not too many people are as crazy as myself. A: That’s true. V: So, with our blog of Secrets of Organ training and these podcasts do we try to help people become as crazy as we are or not? A: I don’t know what you mean by it, but… V: A little bit more similar to us or not? A: Probably yes. But you know it’s good sometimes to sight-read from the clefs, not too much probably but because we still have editions and use them such as eastern German edition of Peeters which has published lots of work by J. S. Bach and Buxtehude and other German masters and it has some spots that you have treble clef and bass clef but sometimes the C clefs appear. Not for a long time, maybe for like 2 lines or 4 lines and it means that if you want to play from that edition you have to read C clef because it wouldn’t just make sense for you and the note to write down those spots, to transpose them to like treble and bass clef. V: It’s like driving the car with stick shift and automatic shift. Automatic shift is easier, you have just the gas pedal and the brake pedal. But stick shift you have to think about the clutch and about manipulating with your right hand the gear. You see, not everyone prefers to do that extra work today, right? A: Yes, especially in the US. V: But guess what kind of cars do racers drive in marathon drive, you know car races. Of course, not automatic but manual shift. A: Yes, you can do more in that car especially in extreme situations. V: So guys, if you are satisfied with your current level of sight-reading ability then reading treble clef and bass clef only is surely enough. Right, Ausra? A: Yes. V: But if you want to go beyond that and advance to the unknown world of something that was done in the past or some things that people with lots of experience do today, it doesn’t hurt trying practicing other clefs. Maybe take one, just one clef and do sight-reading for one month in that one clef. A: Yes, that’s true. Trying some music written for alto for example because alto instrument plays from the alto clef. V: Or you could transpose because reading clefs is an exercise in transposition. A: That’s true, yes. V: If you take any kind of melody which is written in the treble clef and pretend it is in the bass clef, right? You could play it with your left hand and play two octaves and a sixth below so basically it transposes up a third interval, right? A: Yes. V: So you know two clefs very well now. Treble clef and the bass clef. If you pretend it’s not a treble clef but let’s say soprano clef you can do the same with your right hand. You just simply transpose to another key. So that’s what I did also. And you could do that too. That’s why it is beneficial. It also helps for improvisation because then in your mind you transpose the themes in various keys simply by changing the clef. A: Yes, and some actually solfege systems use that movable do, so called. And I think it’s right from the beginning from early age learn how to transpose, how to change keys very quickly. V: Yes, so, our Organ Sight-Reading Master Course is not the only way to improve your sight-reading, of course. You could just as well take any collection of music that you like and simply open it and practice one piece a day and in nine months you will improve a lot, right Ausra? A: Yes. V: But what I did which you will not find anywhere else is that I transposed those fugues for the Art of the Fugue to various keys. Not only from the original key of D Minor but to various keys with ascending numbers of accidentals so you could sight-read in all the keys, in minor keys, not in major keys. Then as a supplement of this course, as bonus material, I think we have seven additional weeks of legato, romantic organ settings based on the chorale preludes by Max Reger. So it’s also beneficial to expand your sight-reading into romantic legato style. Thank you guys, this is Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: And remember when you practice… A: Miracles happen.

Comments

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 158 of #AskVidasAndAusra Podcast. And this question was sent by Steven. He writes: Good morning Vidas, Thank you for posting the explanations, guidance, and helpful suggestions in the "Ask Vidas and Ausra" series. I would also like to submit a question to this series, if I may ... Organists today know to use articulate legato (so-called "ordinary touch") in all the parts when performing early (pre-1800) organ music, such as the fugues of Bach and other polyphonic pieces, and to employ legato and all of its associated techniques for all organ music written during or after the 19th century, unless otherwise specified by the composer. It's conceivable though, that in the course of our studies we may run across a polyphonic piece, such as a stand alone organ fugue, written pretty much in 18th century common practice style by a modern composer ... where the music is very busy and actually sounds in places like it could have been written in the last half of the 18th century by an acolyte of the Bach school ... and the score has no indications about the touch. All we know is, it was written in the 21st century. In this situation, how do we determine a starting place for the touch? ... do we follow the rule that the date of composition in each and every case determines what kind of touch should be used and employ legato in all the parts as a starting place ... or should we take the polyphony of the piece into consideration and employ articulate legato from the beginning to keep all the moving parts clearly audible to the listener? I was wondering how you and Ausra may feel about this ... whether the music's date of composition should be considered more important than it's style when choosing a starting place for the touch. Thank you once again for all the help, aid, and assistance, it's much appreciated. Steven V: As I understand, Steven asks about the situation when a person creates a modern composition but written in the old style, right Ausra? A: Yes, and that’s what I understand from the question. V: And what should the touch be? What’s your opinion today? A: Well, you know, if it’s written in baroque style, let’s say a fugue in baroque style, I would use ordinary touch. That’s my opinion. What about you? V: It’s the same as improvisation, I would say. Whenever we improvise in the historical styles, we use the touch of those styles, even though it’s improvised today, in the 21st century. Right? Somebody could even record this improvisation and transcribe it into musical notation and make it a finished, polished piece, and it would sound like more or less early composition but created today. A: Yes, because I think the style is more important the the date that the piece is written. Because nowadays all those styles mixed up together and you can create whatever you want. And if you feel that sort of style is more close to you, or you are more related to it and you create compositions like this then they definitely have to be performed with ordinary touch. That’s my opinion because otherwise it might just sound muddy and unclear. V: I’m just trying to think of any recordings that I heard recently when improvisation was done in the old style by living of course performer. But none come to mind, right, because every good improviser knows the difference of touch in historical styles and tries to emulate that touch. Although, in the past might have been some people who played baroque style polyphonic pieces like that. But that’s because everyone else was playing legato at the same time, baroque pieces. Right, Ausra? A: Yes. I think so because just tendencies are like this in those days and everything changes and we have talked about in earlier podcasts. V: Yeah. I just remember now, one instance I wrote seven chorale improvisations very early in my career. I think just after graduating from UNL, and those were based on my improvisations. I recorded them and transcribed them into musical notations, and then I thought maybe somebody could publish them, right? That was before the days of this blog of course, because today I would just post it from the internet to myself, and send it to Wayne Leupold Editions, and after while I receive and answer, a very nice polite answer, that, ‘it’s wonderful that you are interested in submitted for possible publication’. And those pieces could be considered in the stye of Crebbs I would say, not Bach, but a student of Bach, let’s say. So when Leupold wrote that, however nobody can really compete with Heir Bach, Master Bach, right? So he doesn’t see or didn’t see the point of publishing early sounding pieces today where there are thousands of original music written. So I stopped doing this, of course on paper. Maybe on the instrument is a another story, when you improvise. What do you think about that Ausra? A: Yes, actually, you know, it’s better probably to leave that early style for improvisation already, instead of composing in that kind of style, but of course we have free will to choose for ourselves. V: Exactly. Let’s say Bach would have thought the same and would try, would have tried to imitate styles of early composers who came before him. And he did actually. A: He did, actually, yes. V: But while doing that, he did this very creatively and combined several styles in one piece; Italian, German and French. A: And actually yes, you can hear in his compositions and see and hear the early styles Stile Antico, so called, and you know the baroque, high baroque style. That was his contemporary style, and then you know, you can already get the tendencies of actually that period that came after baroque and between the classical style. V: Gallant Style. A: Gallant Style, that his sons used when composing and creating compositions. So basically Bach observed all those tendencies and used them in his compositions. V: I would say today, if you want to be original, you have to combine several sources, sources of inspiration, not one. A: Yes, because so, so many things are already written and composed and sent, so you probably just have to mix things together. V: Exactly. Take one realistic approach from one composer that you like, another from a another school, right? Maybe if you like polyphonic you can keep that but add special specific modal writing style that you like from the later schools, right? Something that is rarely combined, and that will make your music more unique. A: Yes, it’s like Paul Hindemith created Ludus Tonalis, and of course I think, the inspiration for him to compose probably was from Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier. V: Yes. A: Or like Shostakovich also played relative too. But still we have to have our own unique style, but of course we know that they studied Bach too, so that’s the way how things should be done. V: I think our final word of advice besides articulating early style of music whether written or improvised today, should be, I think, be very open minded and look broadly at your influences, right? And then you can mix things up, creating different order. And you don’t know what will come out. Maybe the result will not be something you like. Maybe that will be another level of training that you do. But maybe the next step will lead to something with more interest, right Ausra? A: Yes, because I think you need to mix the elements of early and modern even if you are creating in that early style. Because if you would just create in that early style it would be like copying that style, and if you will not add anything new, then, I don’t know if it is worth doing. What do you think? V: In music, musical world today, there isn’t much success with this, I think. I think only in improvisation, yes, but if it’s written piece, people will not be too impressed if you just imitate somebody’s style, right? That’s in music, but let’s say in art, in art visual art, if you imitate style of dutch Renaissance or Baroque or something, if you can do this, people somehow will be very impressed and could pay a lot of money for just observing the pictures or photos of your paintings today. That’s a very weird situation, right, to create something old fashioned and people will be very happy. Because, you see, people like to look at stuff they could recognize, right? A: Yes, that’s true. The things that are familiar to them. V: That’s why people keep drawing pictures of Superman and Batman and other superheroes, right, characters. They are not inventing their own. Sometimes they do, but not always. They recreate them from the past movies, let’s say, or stories. Because their audience loves to look at stuff or read stuff that is familiar, right? A: Yes, that’s true. V: That’s why we keep playing masterpieces of 17th, 18th and 19th century in the concerts of organ music, right? Instead of constantly creating something original in 21st Century style. Right, Ausra? A: Yes, that’s right. V: We do sometimes create and incorporate but not always. There are people who do exclusively unique stuff, but they are, I think, in the minority. A: Mmm, hmm, that’s true. I think it’s hard to be always original. V: Yes. So with that optimistic note, we could end this discussion, and we hope to get more of your questions and feedback. Please send us. We love helping you grow as an organist in various spheres in organ playing. Thank you guys. This was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: And remember, when you practice… A: Miracles happen! Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. Vidas: Let start episode 157 of Ask Vidas and Ausra podcast. This question was sent in by Marco and he writes: Hi Vidas, I'm an organ student. I'm trying your method of subdividing a piece in fragments and voices and it's very helpful. My problem is that I find the practice quite stressful mainly for the following reasons: 1. There are sometime fragments that I cannot play correctly no matter how many times I repeat it. 2. I easily become anxious when I repeat a fragment, especially for the third time, because if I make a mistake I have to start again and repeat it at least three more times. Do you have any suggestion to make the process less tiresome? Thank you, Marco V: Do you think Ausra that people should be so severe when they practice a piece of music? A: I don’t think so you can hurt your nerve system if you will be always anxious and be so stressful about your practice. V: Almost you can feel that a person feels a guilt right, about making a mistake and feeling bad about himself or theirself that this mistake was made. Actually there is a saying that the person who makes the most mistakes will win actually in the long run. The person who fails the most will win. Do you know why Ausra? A: Why? V: Because they will try it many more times than the other person. A: That’s true. And to know I just thought about, you know, him saying that sometimes he makes mistakes and you know he cannot not sort of correct them and then he gets frustrated because he knows that has to repeat that part at least three more times and I’m thinking you know if there is certain spots that are possible for you to play correctly it means that you are doing something wrong in that spot and I would suggest for you to revise those fragments. Maybe, you know, you are playing them too fast. V: Or, you are making the texture too thick. A: Sure, maybe you are using a wrong finger because something is probably not right in those spots. Or, maybe you are just too anxious to get a good result. Things like this take time and it’s normal. V: Remember in our school there are a lot of students banging the piano as fast as they can in short fragments repeatedly over and over again like ten or twenty or fifty times. A: And it’s funny but they are repeating the same mistakes all over. Over and over again. V: Do you know what insanity is? The definition of insanity? A: No, I don’t know. V: Alfred Einstein said that “Insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results.” The definition of insanity. A: No. V: So, simply you have to change something in order to expect different result. And I’m not meaning Marco or any of our students in this way. I’m just illustrating how extreme this approach can become, right, if you play too fast or the the texture is too thick. For example, if you’re not ready to play without mistakes that fragment, maybe you could play just one line, one voice. A: Sure, but you have to know to do something about it. V: Change. A: About that, yes. V: You make a mistake and you are not satisfied with that mistake. That’s OK even though you are feeling angry or frustrated with yourself is not the best feeling but OK for now let’s say that you are angry. You accept that. You admit that you are angry and then you think “What can I change about the situation or about my feeling of the situation.” Right. If I cannot change the situation why should I become angry. Right. If I can’t change the situation then maybe I become less angry about that. A: Yes and no, if some particular spot give you so much trouble maybe just let it to rest for a while. Maybe you know, stop practicing that piece for a day and come back to it later, you know next day. Or, do a break of two days, because sometimes you know, you need to give for things time to rest and then you will go back to them and things will work well. I’ve had this experience many times, have you had it too? V: Obviously, yes. Of course what happens at the time when you rest, your mind is bombarded with another set of information and your old influences and inputs, informational inputs are no longer the current ones and you maybe tend to forget what happened bad in your past, right? And when you come back to the old spot when you made mistakes your fingers might feel like their at a fresh spot and forget that this was a difficult spot. A: Yes. V: So, maybe a week or so of playing something else would be beneficial and then coming back to the old spot. Ausra, do you make a lot of mistakes yourself when you practice? Do you allow yourself to make mistakes when you practice? A: Actually, no because the more mistakes I will make during my practice, the harder it will get to correct them. V: Exactly. So, you are doing something different that a lot of people, right? You are not allowing yourself to make those frequent mistakes. A: That’s right, so you just have to be really focused when you are practicing. V: Even at this level, right, very far advanced level we could play a piece, a familiar organ piece and make many mistakes if we are not careful, if we are playing too fast, if were playing it with the wrong fingering. You could do that, but we don’t allow ourselves. For example this morning I recorded my sight reading of BWV 552, the E-flat Major Prelude and Fugue by Bach which will later be used for transcription purposes of fingering and pedaling from the new score. So, I had to play almost cleanly and without mistakes so that people who will help to transcribe this score will understand what I’m doing, right, and the choices that I’m making with fingering would be more or less correct. Of course, I can edit them later in the first draft of the transcription. But, I tend to use more or less logical fingering, right? A: Yes. V: So how do you do that, Ausra, at the early stages of development, if a person doesn’t have advanced skill of playing difficult and advanced organ music. A: I think the most important thing at least for me is to know to practice with my actually mind first. That no if I have no sort of fresh head when I can practice. If I feel tired that I cannot understand what I am doing I stop practicing because I just don’t like that purely mechanical playing. V: So it’s a complex phenomenon. You have to understand how the pieces put together. In order to do that you have to have a good grasp of music theory and harmony and musical analysis and form. Right? So you think what the composer thought when he or she created this piece. Moreover, you have to have your own experience at creating music in the moment like improvisation or in a written form like composition or in the perfect scenario, both. Right? That would be the ideal situation. Of course, so my advice for all the people who are listening to this would be to have a complex education and expanding your entire musical horizons not only organ playing from score but many supplemental things. A: Yes, and always listen to what you are doing. That’s important too. Because so many people are just playing whatever, fast and loud. V: Do not worry about how fast or how slow you will achieve that results. Do not worry how much there is still to learn, right? And how many years it will take to perfect your art. It doesn’t matter at all. What matters is that you perfect your art just one percent a day. One percent. And every seventy-two days this percentage will double and at the end of a year you will perfect your art, your complex organ art. Not only organ playing or sight-reading skill, but everything together put together. You’ll perfect it thirty-eight hundred percent if you do that every day. That’s all. That’s enough. OK. So I think that this is the best we can hope to inspire you today. Go ahead and practice and don’t be frustrated with your mistakes. Or, even better, play as slowly or as transparently that you will not make those mistakes at all. A: True. V: Thank you. We hope this was useful. Please send us more of your questions. We love helping you grow. An remember, when you practice… A: Miracles happen. Last Tuesday it was supposed to be my regular practice at my church. My practice usually consists of pieces I'm currently working on, improvisation and sight-reading.

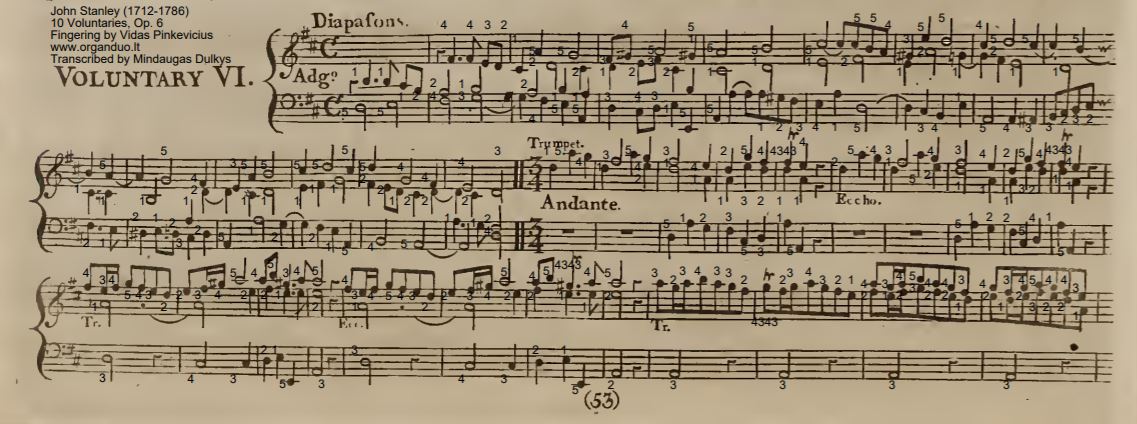

Some things got in the way and I had to leave before I had time to sight-read anything that day. Luckily, in the afternoon during Unda Maris organ studio rehearsal, my student Mindaugas Dulkys was playing Voluntary in D Major No. 6, Op. 6 by John Stanley (1712-1786) from England. I wanted to show him how it's done and figured I could play it in a slow practice tempo. Not only I wanted to help him, I thought, but I also wanted to sight-read something that day. Luckily, I had a video camera with me and recorded everything from the high angle so that my fingers were clearly visible as I usually do when I sight-read. Of course, I had an idea to turn it into a practice score to help other students as well. Thanks to Mindaugas Dulkys for his meticulous transcription of the fingering from my slow motion video into original edition from 1752. Intermediate level. Manuals only. PDF score. 3 pages. 4 movements: Adagio-Andante-Adagio-Allegro Moderato 50% discount is valid until February 23. Check it out here This score is free for Total Organist students. Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 156, of #AskVidasAndAusra Podcast V: This question was sent by Monte. He writes: "Maybe one day you could create a course revealing how you decide to articulate legato fingering for the Bach scores that you recently made available. It’s kind of mysterious. The Ritchie and Stauffer organ technique book has a lot on this, but having you explain and demonstrate adds a lot of value." V: That’s an interesting question, right Ausra? A: Yes, it is. V: We have talked a lot about the principles behind early music fingering, but we haven’t created a step-by-step course on this, right? Like, for example, what Monte probably means, is that the camera would point somewhere from our shoulder, right? And as we are playing it, this choral or music order let’s say in this case Bach music, the camera would point to our hands, right? And then as we’re playing, we should probably demonstrate and explain the changes of the fingering we’re making. A: Well, yes, and I would like actually to separate these things; you’re talking about Bach as early music. I would not call Bach music early, and I would not use fingering in Bach music. For example I use when I play, let’s say, really early pieces, Estampie Retrove from Robertsbridge Codex, or Faenza Codex or really early stuff. Because Bach music is already such a complex music that you can not sort of use only early fingering. For example, in many cases you have to use the thumb or the black keys or accidentals, yes. V: I think you are right Ausra, because simply this of fact; Bach uses many more accidentals. A: I know, and the more accidentals you have, the more you have to use things like thumb under, or thumb on the accidentals. And all kinds of tricks, and you know what I think Monte is talking about is that he wants to get from us some sort of a system. But I don’t think that there is complete system that you can apply to any given piece of music, because each music even by J. S. Bach is so unique that sometimes you have to have unique solutions. V: And I fully agree with you. I just want to add of course I’m talking about Bach because that’s what Monte is interested in. And we’re talking about early music. And the only thing that I wouldn’t do with Bach in comparison to real modern music or romantic music is probably finger substitution and glissando. A: Yes, that’s definitely. V: You could get away without that. A: Sure, sure, you wouldn’t want to do that in Bach. V: Even when you have two voices in each hand, you could still play without finger substitution, I think, in most cases. But there are exceptions, there are exceptions, even in Bach. So remember we could each talk a little bit about our experience in playing E flat Major Prelude and Fugue, because you are practicing it currently for the upcoming Bach birthday recital. And I, this morning, actually recorded a video with the camera pointing right above my hands so that my transcribers could transcribe fingering and pedaling from this video played at a very slow practice tempo. And probably this score of E Flat Major Prelude and Fugue by Bach BWV 552 will soon be available if you want to master this piece without much frustration in figuring out your own fingering, right? So Ausra, do you use a lot of thumbs on sharps and flats, lets flats because it’s E Flat music? A: Sure. Not a lot but I use some definitely, yes. You cannot avoid that especially when the texture is so thick. If you would think about the first fugue, for example, there are two lines that are just killing me in that fugue, the ending of it and then ending of the first half of it. It’s really very complex. Sometimes I just feel that I’m playing with both my hands fully with all my fingers at the same time because of the thick texture. Don’t you get that feeling? V: Absolutely, it’s a five part texture. A: Sure. V: Right? And I can guarantee, that if you wrote down your fingering, or somebody recorded you playing this piece from above, right, and if our transcribers would transcribe your own fingering and compare it to my own fingering, it would not necessarily coincide, right? A: Yes, but, V: And the learning also choices might be different. A: Well, I think on the pedals we would agree more than on the fingering probably. V: But when fingering gets very individual because the hand layout for each person is a little bit different, right? And the span of the palm is different for each person. You can, I don’t know, can you reach a tenth? A: Some of the times I can reach with my left hand, not with my right hand. V: Right. So, there are people that can hardly reach an octave. A: I know. V: So then they figure out some other ways to play those middle voices. Maybe they sometimes migrate from hand to hand. A: Yes. For example, composers like Cesar Franck, he had such a wide hand. I was already, I almost forgot about it but recently I started to play sort of the second chorale in d minor by Cesar Franck which is probably my most favorite piece written by him. And sort of I remember how wide some of the intervals are. And if you have that Dover publication of his complete organ works, it has a picture of him. V: The famous painting. A: Yes, and you can see how wide his hands are. And in pieces like Choral No. 1 in E Major and in his Priere and his 2nd Chorale in B minor, those intervals are just enormous. And you just have to do transfers with one hand, at least. V: It might not be a painting but every photograph of him. A: Could be, could be, yes. V: So going back to let’s say, example Bach’s BWV 552, we have talked about importance of placing the thumb on the black keys. Of course sometimes even in this advanced E Flat key, we have instances when you could play with early fingering. Let’s say if you have parallel Intervals of thirds or sixths. You easily play thirds with 2-4, 2-4, 2-4, if they’re not too fast. Or the sixth could be played 5-1-5, and 5-1-5. Don’t you think, Ausra? A: Yes, there are places like this. But of course another thing which is very important when practicing this piece or any other Bach pieces that has multiple voices, that you have to know which hand is playing which line. Because it would be very easy, that’s why I like trio sonatas so much, that you have a single voice for each hand and one voice in the pedal. And you always know that is that way throughout the piece. But in a piece like E flat Major, Prelude and Fugue, you know sometimes you have to pickup a line from the bass line and play with your right hand, and sometimes you have to pick up some music from the treble clef and play with your left hand. And it’s very important to mark you score in those particular spots. V: Before. A: Before writing down anything. V: So, when you write down fingering for yourself, do you notate divisions of the hand for the entire piece or go page by page? A: Well I do it for the entire piece because it’s very important. V: I have a different method because I’m very lazy. I tend to have a short attention span and I only can focus at one page a time. So when looking at one page at first, I divide the hands, and look at the places where my middle voice and my great from hand to hand, notate it in pencil, or if I’m doing this on the computer, I do this directly on the computer. And only then I would add fingering, right, for that particular page. I don’t go to the next page right away. So Ausra, do you think that this system is better than yours or not? A: I don’t know, it just depends on what your character is, or how long can you stay focused. I think the result would probably be the same. V: Of course, but still you will need fingering, right? You will complete the fingering whether you are working for one page at a time or the entire piece. A: Yes, and for doing this division thing you have to sight-read the piece at the beginning to feel both hands. We often talk during our podcast, that you have to learn things in combinations and start to play everything together, right at the beginning. But you have to sight-right a piece first, with both hands and probably both feet. And this doesn’t matter that you may play half of the notes wrong. But when will you get to know the understanding where you will have to do the division between your hands. And after that you can write down correct fingering. V: Well actually, if you make too many mistakes, then it might mean that this piece is too difficult for you at the moment. A: Yes, that’s true. Because when you sight-read the piece through it gives you sort of an understanding how long it will take for you to learn it. Not to that final stage. V: What do you mean Ausra? Do you have a system, a precise system of calculating the number of repetitions? A: Well, no. But I sort of have a right intuition for things like this. V: Let me say that I have a system that might work for you and it might not work for you, or other people, but it works sometimes for me. Whenever I play the piece and I sight-read it at a concert tempo, and I make mistakes, I have to record myself, and then play back that recording, and mark the mistakes on the score. And then I will count those mistakes and that will tell me how many repetitions do I need to play, because with each repetition, I usually master one mistake. Is this realistic enough, Ausra? A: (Laughs). Well you know, yes and no, because mistakes are different. Sometimes you can just hit the wrong note but sometimes it might real technical difficulty. But you need many different repetitions to overcome. V: So but I mean of course you have to sight-read it at the concert tempo while recording yourself and counting mistakes. A: Is this possible to sight-read each piece at recital tempo? V: Everything is possible but the result might be something you want to hear of course. A: Yes. Try for example, one of Reger’s fantasies, chorale fantasies, and look how it works. For example, Fantasy on BACH and play it at concert tempo. Good luck with that. Have fun. V: That simply means probably that you need to have many hundreds of repetitions. A: That’s true. V: It’s all about numbers guys. And math is our best friend. Thanks for listening, and remember to send us more of your questions. We love helping you grow. This was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: And remember, when you practice… A: Miracles happen! Would you like to learn J.S. Bach's Kyrie, Gott Heiliger Geist, BWV 671 from the Clavierubung III? If so, my new PDF score with complete early fingering and pedaling will save you many hours and set you on the path of success to achieve the ideal articulate legato touch naturally, almost without thinking.

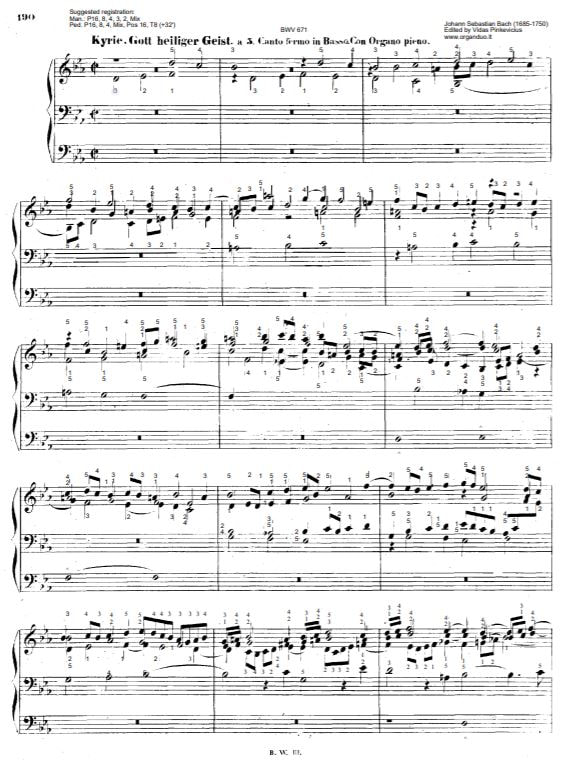

Since this is a 5-voice chorale prelude for Organo Pleno registration, for most of the time, the right hand plays two voices and the left hand also has two-part texture. The pedals have a chorale Cantus firmus in augmentation (long note values). If you liked Kyrie, Gott Vater in Ewigkeit, BWV 669, Christe, aller Welt Trost, BWV 670, Allein Gott, BWV 676 or Dies sind die heilgen zehn Gebot, BWV 678 I'm sure you'll enjoy this piece too. Thanks to Mary for her meticulous transcription from my slow motion video! Advanced level. 4 pages. 50% discount is valid until February 21. Check it out here This score is free for Total Organist students. Vidas: Let’s start Episode 155 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. This question was sent by Leon, and he writes:

“Thanks for the thought-provoking complex question on how some people hate most modern music. Perhaps it would also help to read some texts on the history of music. Irving Kolodin's "The Continuity of Music" would get him to the 20th century. And then if there is a music school near him, or even now via the internet where he could take a course, even a seminar on 20th century music, that would help. As for myself, it seems to be very random what I have liked and not. For example, I do not like much of Xenakis' music, but his lone organ work, Gmeeoorh, is actually very well structured, and one of my fantasies to be some day to play. After a couple of big Bach works and the Reubke sonata. And a Vierne, etc. Bottom line, sometimes nightmares can become part of the dream, and eventually as you remind us: miracles happen!” Ausra, what Leon is saying probably is that music that we dislike in the beginning sort of grows on you later, especially complex modern music. Do you have this experience in your life? Ausra: Yes, yes, definitely. V: Does your taste change over time, or not? A: Sure, of course. I remember when we first met, I sort of liked early music more. And I was a fan of Buxtehude and Bach; and I still am. And I remember you were a fan of Hindemith and more modern music, yes? So...And actually, you know, during our studies in Lithuania, I would say we had fairly incomplete education in terms of modern music. Because all the focus was based on the common period, and we did not know much about early music and, I mean, about the Middle Ages, and Renaissance music, and early Baroque music. We did not listen much, and we hadn’t studied much of it. And also, of the modern music, because sort of my knowledge before going to the United States was ended up somewhere with the New Vienna School--meaning Schoenberg, Webern, and Berg. I did not know much about later composers of the 20th century; and about the beginning of the 21st century. And then, you know, in the States, during our doctoral studies, we moved to the part of music history first, of the second half of the 20th century; and it really widened up my horizons, because I learned a lot about modern music, and you know, composers like Iannis Xenakis, Luciano Berio and you know, many American composers such as John Adams, and I could name many of them. That’s a new world, you know; but of course, if you study modern music, you have to find out what the composer’s idea was when he wrote a certain composition. Because that’s a very important thing, to find out what is behind it, what the idea is behind it--what composition technique did he use; because, you know, if you don’t know about modern composition techniques, these cannot mean anything to you. Like, for example, I studied Luciano Berio’s Sinfonien. That’s an amazing piece, but you know, you have to know how it’s put together, what’s behind it, the idea of composing a composition. Like, all this musique concrete and using collage technique, and like, you know, tonal serialism, and all that kind of stuff. What about you, Vidas? What’s your experience? V: Well, let me say this for starters: Don’t you think that, let’s say, Bach’s music was quite modern for his day, too? A: Yes, I believe so. V: He was quite groundbreaking in many ways. And remember when he played some fancy stuff after returning from Lubeck, when he was an organist in Arnstadt, his congregation complained that he’s playing too dissonant music, right? Among other things. So, he was well ahead of his time in many ways. And let’s say, composers that we think of as very early music, like Sweelinck--he was probably just as modern as any other contemporary composer back in the day, right? And everybody back in the 18th century, 17th century, played “modern” music, “contemporary” music, “music of living composers.” Either they copied the music by hand, or sometimes they purchased very expensive publications, which were rare in those days. But you could not get away just by playing music from dead composers. Sure, people studied ancient art, and Renaissance traditions, and polyphonic masterpieces, but they did that in order to expand their musical horizons and to further develop their own unique original musical style. Don’t you think, Ausra? A: Yes, that’s right. I couldn’t agree more. V: So today, of course, when humanity’s development is so much more advanced, today we have so many styles to choose from, right? And when I first started playing the organ as you mentioned, I liked early music a lot. And I still do, of course! But I didn’t know much about any other stuff, any other developments; and I didn’t know about ultra-modern music. Then I discovered Paul Hindemith and his creative approach that got me hooked; and I started improvising as I understood Hindemith taught. Of course, that was quite ugly in my case...But that was a natural, probably, development of my personality--my musical taste. And I believe the further you study music, and practice music, you are open with your eyes for influences; and you look for influences everywhere--not only in music, in other forms of art, but also in science, in everyday life; you look for those inspirations, right Ausra? A: Sure, and you know, it’s never easy, probably. Think, for example, about Ligeti’s famous piece “Volumina”, composed for the organ. I think the story behind that piece is that it was banned at the beginning. Remember that story we heard I think in Sweden? But now, it’s one of the most common pieces, and sort of exemplary piece of modern organ music. V: Exactly. I think the best you can do is to stay open to the possibility for chance to fall in love with this music. Not particularly with Volumina, but let’s say music that you don’t understand right now: for example, there was a time that I didn’t particularly like music by Charles Tournemire. His music looked like bizarre melodies and rhythms combined together. He didn’t have well-structured form (or at least I thought it was like that); and for example, contrary to this music, Vierne was very well organized and quite well understood by me. So I thought Vierne was more worthy of respect. And then, of course, music by Jehan Alain--oh, he died young, and his music, many of his pieces are very short, but could be short miniatures; but quite recently I discovered that he was quite a genius, right? And Tournemire also was a genius, I believe, because the more difficult thing for you is to analyze this music. The more original it is, the more unique it is, probably; if it’s on the surface, very clear and well-structured, simple, that doesn’t necessarily mean it is unique or innovative or original. There might be exceptions, like with Mozart for example--brilliant poetic simplicity. But in a lot of cases, people, they create something and they then don’t try to go even further than the extra mile, and think that it’s good enough, and this is an exercise music. (And with Vierne of course, that wasn’t the case; he was a unique inventor, and pushed symphonic French art into the new realms of chromaticism; there is no question about it.) So each of those composers sometimes I don’t appreciate at the beginning, grows on me. Whenever I spend quality time with that composition. So now, I try to be open to new musical compositions and try to sightread every day, some unfamiliar music, some bizarre musical composition that I can get my hands on. Would that work for Leon, do you think? A: Yes, I think so. I think it would work on anybody. Because it’s an important thing, you know, to study, to analyze, to appreciate modern music. V: Because you have to understand, we probably need to express ourselves, express our inner ideas, let them out. We have some songs that we need to sing, of our own--not only songs that Bach wrote, or Scheidemann wrote, or Sweelinck wrote, or Vierne wrote, or Tournemire wrote, or those masters that we adore, right? But sometimes we have to try to create something. And this will be, of course, not perfect, just for starting out; but then, if you understand the need for this, then you obviously start to look for influences and inspirations wherever you can, especially modern music. If you are inclined to create. And I think every human being is sort of inclined to create. Sometimes we’re afraid to create, but nevertheless, it’s good to try. And sometimes, it’s really fun. A: Yes, it is. Even when you study a modern score, it has all that graphic design, sort of unusual for the eye--it’s basically a masterpiece. V: And a lot of people don’t understand that, and say, “Oh, it’s nonsense, it’s rubbish, it’s too dissonant,” right? A: Yes, but I think the more time that we spend with that music, the more familiar you get with it, the more you can appreciate it. I mean, you don’t have to love it and play it every day, but you need to learn to understand it and to appreciate what the composers did. V: Because that music came from the composer’s mind, from the abyss of the human mind, you know? There’s a saying--you remember the name of the professor who told that, “The human mind is an endless abyss.” That was the former director of music department at University of Nebraska in Lincoln. His name was Raymond Haggh. A: Yes. V: And he had this saying, especially after grading freshman papers… A: Students’ papers! V: “The human mind is an endless abyss.” So, try to go further into this abyss. It’s interesting, and you will be surprised what you will find there. A: Yes, and have fun studying modern music. V: And guys, please let us know if you have such experience when the more dissonant music and more advanced music sort of grows on you, and you start to like it later in your life, after spending some quality time with it, right? It would be very interesting to know if we’re not wrong. A: Yes. And remember, when you practice… V: Miracles happen! AVA154: Today I Practiced As You Taught The C Major Scale. But How Do I Learn Not To Look Down?2/12/2018 Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. Vidas: Let’s start Episode 154 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. This question was sent by Shirley, and she writes: “Hi Vidas, I have piano only to Grade 6 but am just starting the organ. Today I practised as you taught the C Major Scale. But how do I learn not to look down! Would you please tell me the order in which I should watch your videos? Blessings, Shirley.” Uh...Ausra, do you think that people should really watch our videos? A: Well, it’s up to them. But I don’t know. I would spend that time practicing. V: It’s better to start playing right away. A: Yes. V: If you are struggling with a specific problem, right, you Google it online, and you come across our videos. So of course take a look, and watch, and apply. But then, right away, come back to the organ bench, and practice what you have just watched. A: Sure, because you know, just watching will not make you a great organist. V: “Oh, I thought it would make myself a great organist! I would rather watch 100 videos than practice, let’s say, 100 hours!” A: Well, but I think it’s better to practice 100 hours. V: But it’s easier to watch 100 videos! A: I know it’s easier, but the result will not be the same. V: Umm...Do you mean that watching videos is not beneficial at all? A: Well, it’s beneficial to some point, but I think it’s more beneficial to practice. Let’s say if you...It’s like 1 to 10: let’s say if you watch a video let’s say for 5 minutes, yes, then go to the organ and practice for I don’t know, 50 minutes. V: I thought of another way of explaining this, too. You’re saying a good idea, but I think people should understand that watching random videos on the internet will not teach you a system, right? A: Yes. V: Of playing the organ. What Shirley is probably meaning here, is she would like to know the order in which we would recommend her to watch our entire video library, right? And she hopes, probably, to learn a system that we use from this. Is it even possible? A: I don’t know. What do you think about it? V: You see, these are videos designed for public use, right? For everybody. And they’re not created as a course from the easiest to the most advanced materials, right? A: That’s right. V: Like these podcasts, right? People send us questions, and we are answering them and helping them grow (hopefully). But they’re not necessarily from the easiest to the most advanced level, right? A: That’s right, yes. V: Sometimes they’re in random order. And if you want some video courses and system which go gradually in advancing order, then of course we recommend our training materials. We have other videos like that. A: That’s right, yes. V: But Shirley has to ask herself, what is her goal in organ playing, right? Because we have many, multiple courses for multiple goals. A: That’s right. V: For example, for Bach playing, we have a course on 8 Little Preludes and Fugues, and they go from the first to the last, and preludes and fugues are discussed, and it’s very gradual. They learn harmony, right? A: Yes. And hymn playing… V: And improvisation. A: Yes, and sightreading. V: Sightreading...Do we have videos on sightreading? I don’t think so. I think we have PDF materials on sightreading. A: Yeah. V: The same with pedal playing. It’s a PDF format. A: Yes, that’s right. V: So, you have to ask yourself what is your goal, and then see what kind of materials you need from us. A: Yes, and talking about that: C Major scale, she asked if how to not look down. I think it’s okay, at the beginning, for starters, to look down at the pedal. I think your goal is that eventually you could play that scale without look at the pedalboard. What do you think about it? V: Yes. A: I think it’s fairly okay to watch your feet, when you are just a beginner. V: Sure. So guys, I think if you are in Shirley’s situation, also spend more quality time on the organ bench, and just occasionally glance at some videos, which are not part of the course, of course. That would be more beneficial. Ausra, would you think that watching videos is good for inspiration, by the way? A: Yes, I think it’s good for inspiration. V: Like if you have a specific organ piece that you want to master, but you don’t know how to play. A: That’s right, yes. Or sometimes you don’t know which piece to play; then it’s maybe also good to watch some videos, and hear some music, and then to decide what you want. V: To broaden your musical horizons, right? A: Yes, that’s right. V: Sure. A: But it wouldn’t be good to pick up a video that you like, for example, and try to copy it, just by watching or by listening. V: Yes. Thank you guys, this was really fun. Apply our tips in your practice, and...we cannot guarantee, but we almost can guarantee that in a few months, you will see the results slowly developing, right? A: Yes. These things take time. V: For each, the time is their own, and it varies. As they say, “Your mileage might vary.” With cars, right? A: Yes; so the same with playing, and achieving progress. V: Excellent. Please send us more of your questions, we love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice… A: Miracles happen. Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 153, of #AskVidasAndAusra Podcast. Today’s question was sent by David. He writes: Hi Vidas, Thank you for your encouraging emails. They have made a very big difference to me. I have always enjoyed playing the organ but you have given me a renewed enthusiasm, a sense of achievement and deeper enjoyment. Cheers, best wishes to you and Ausra, have a good Christmas break. I am getting better, but my pedaling is in need of work. The organ I use has a 'special' pedal coupler called 'MB' or Manual Bass. This takes the 'signal' from the lowest note played on the Great manual and treats it as if it were a 'signal' from the pedal board, thus allowing the pedal stops to sound from the Great. If you had no stops out on the Great, you could use this coupler to play the pedal pipes instead of using the pedal board itself - although you could only play one note at a time as it selects the lowest note played from the Great only. I am afraid this works so well and it is so easy to give a full organ sound, that I rarely use the pedal board, other than for pieces I am really familiar with, e.g. wedding music! I watched your video on playing a C major scale on the pedal board, this was so helpful that when I saw your 10 day pedal playing challenge, I thought it was exactly what I needed. Early this year I bought a special pair of organ-master dress shoes which also help. I have quite big feet (UK 11 - EU 46) and normal shoes make it difficult to be precise. The higher heal helps as well and the soft sole is a great advantage with just the right amount of friction. I live in Sheffield, South Yorkshire in England. Best wishes, David V: So, Ausra, I think it’s good that David is playing with the right kind of organ shoes. A: Yes, it helps a lot. V: Some people prefer to play with socks, some people use other kinds of shoes, but eventually you need to choose the right equipment, right? A: That’s right. It makes a big difference. V: So, this manual-bass coupler is a very interesting phenomenon. Have you ever met it or seen it on the organ? A: Actually, no. I haven’t. V: I saw it just once or twice, but only on electronic organs, like Allen digital organ. I remember, we have a studio organ at the Lithuanian Academy of Music, and the principle is this; if you engage this coupler, you could play pedal stops with your hands. A: Well, but that’s, that is cheating. V: That’s what they thought. That’s what they thought. It’s only for people who don’t use feet during their playing. A: I know, but, but, but, I just don’t imagine how can you play organ and don’t play the pedals. V: It’s little bit, too bad, right, that David is not always taking advantage of the pedal board. And you can sometimes even forget how to play your feet if you do it too long with your hands. A: I know, you have to practice your pedals every day, until you will feel comfortable. Because I think this is the most fun part of playing organ, is to be able to play pedals. V: Definitely. It feels like you are dancing, actually. Do like to dance, Ausra? A: Well, I like to play organ more. V: But does organ pedal playing remind you of dancing? A: Well, maybe a little bit, yes. V: To me, it reminds me of using your entire body, even, so, I’m not a dancer myself, but I danced a little bit when nobody was looking. So it feels like similar motion. It was really a weird situation, to see me dancing. So, of course, I play better with pedals. A: Yes. V: Have you seen me dancing, Ausra? A: Yes, I have danced with you? V: What you do think? A: (Laughs). I think you play organ than you dance. V: Do you think I have hope to become a better dancer, like I’m the organist now? A: (Laughs). I’m sure I don’t think so. Sorry! V: That’s too bad. I was going to apply to ballet school. A: Heh, heh, heh. V: But now I’m crushed. A: Yes, sorry for that. V: You’re good at crushing my dreams. What dreams could I crush on you now? A: I don’t know. I better don’t tell you my dreams, so you cannot crush them. V: Yeah. Guys, keep your dreams to yourself. Don’t tell anybody because some people can take advantage of your dreams, and uh, you know, make fun of you. A: Yes, don’t tell your dreams to Ausra; she is cruel. That’s what you meant. V: I will not say it out loud. A: Okay. V: Excellent. So I guess we have to help David to get better with pedal playing, don’t you think? A: Yes. V: The first step he needs to take is simply believe that it could be done, with time. A: Yes, of course. V: Maybe a few months, maybe a few years, but eventually pedal playing will get easier. A: Because you know, if you avoid them, you will never feel comfortable about playing pedals. V: You have to face your fears, right Ausra? A: Yes V: It’s like, if you are afraid of spiders, you have to get into the spider’s web, and you know, get comfortable with ten or one hundred spiders. Ausra is looking now for spiders because I’m afraid of spiders and she would bring a few of them on my head now. A: Well, I think you are just pretending that you are afraid of spiders. V: I’m not afraid of spiders when I draw them, actually. So, I better try to draw them with pencil or a pen. But when I see them, it’s very frustrating and scary. What about you? A: I’m afraid of snakes. V: So, are you afraid of drawing snakes? A: I wouldn’t like to draw a snake actually. I hate them, you know, in anything, in nature, and also in drawing. I just don’t want to look at them. V: But what would happen if a snake appeared on the pedal board? A: Well, it would be the biggest nightmare of my life. V: You would be playing like a dancer then, right, like a gigue. A: Well, I think I would just scream and run. V: So, guys, if you want to I think Ausra is saying, correct me if I’m wrong, if you want to get better with pedal playing, put some snakes on the pedal board, and force yourself to, to, you know, avoid them when the bite you. But still keep playing, right Ausra? A: Ha, ha, how funny. Don’t do that. Don’t listen to this! V: My advice always works, don’t you think Ausra? A: Maybe not about snakes. V: Okay. I will try it myself then and then I’ll let you know how it goes. So, of course it’s important not to skip pedal practice, for David. A: That’s right, because you know, don’t use that coupler, unless you use it on very special occasions, but don’t use it, on a regular basis. V: If you’re so used to that button, maybe it will be very hard for you at the beginning, maybe, the first couple of months, you know, to avoid playing with your left hand, the pedal line. But later, you’ll thank us, actually. A: I know, because otherwise, how can you play real organ repertoire which you know, has right hand and left hand and pedals. So you will not be able to play it, if you use this coupler. V: Or maybe David doesn’t have a goal to or dream to play real organ literature, don’t you think? A: I don’t know. It’s hard to tell. V: If that’s the case, maybe he should challenge himself a little bit, of playing unfamiliar repertoire specifically created for the organ. A: Yes, I think that’s a good way. V: And in a few months, he will start to see some progress and get hooked on this. A: That’s right. V: An entire world will open up for David, and people like David, maybe who are also struggling with playing with their feet and would rather use the manual-bass coupler instead of real pedal playing. V: Thank you guys. I hope this was useful, and please send us more of your questions. Ausra and I love helping you grow. V: And please remember, when you practice… A: Miracles happen! Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. Vidas: Let’s start Episode 152 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. And this question was sent by Willem. He writes: “Maybe a dumb question but how would you play your new “10 Day Pedal Playing Challenge”, two octaves lower than is written?” So, the situation, Ausra, is that, remember we took those exercises from the French solfège treatise, right? And we applied it to pedal practice, and created a course on it. Do you remember it? Ausra: Yes, I remember it. Vidas: Why did you need those sightreading exercises for your solfège classes? Ausra: Well, that’s a part of the curriculum. Vidas: Mhmm. And specifically for you, of course, children in school have their own methodical material, but you had to prepare something of your own, right? Ausra: Well, yes. We have some special occasions, but we need special exercises, so this was one of those. Vidas: Was it for a special competition? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: Excellent. So...we searched for suitable material, and we found those exercises in the French system for singing solfège. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: For ear training. And then we thought, “What would happen if people would play it with their feet on the pedals? Would that be a good idea?” Ausra: “Yes! We could do pedal exercises!” So that’s what we did. Vidas: But of course, people sing those exercises in treble clef, right? Ausra: Well, not necessarily; if you are a man, after puberty, of course you sing in the bass clef. I mean, not in the bass clef, but in the range of the bass clef. Vidas: Yeah, you transpose it one octave down. Ausra: That’s right. And that’s what you do when you play the pedal on the organ, too. Vidas: You just have to figure out whether you need to transpose it one octave lower or two octaves lower. Because...what’s the lowest note in those exercises? Primarily treble C. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: Like soprano. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: So, if the lowest note for the feet is C, this means you could be playing one octave lower in the tenor range, or two octaves lower in the bass range. Right? Ausra: Yes, sounds right. Vidas: Anything else you would like to add? For people who will be practicing this course? Ausra: Well, I’m just thinking is it harder to sing those melodies than to play them in the pedal? And I would think that some of them are harder to sing, actually. Vidas: Definitely, because of those high leaps, up and down; and to play those leaps you could use both feet. Ausra: That’s right. Vidas: And to sing them, you need to use your voice, and it’s particularly challenging sometimes. Ausra: It is. Actually, everybody complained after that competition, that these were hard examples! Vidas: Oh, tell us a little bit how it went--those singing the part, of course! Ausra: Well, it went fine. But everybody complained afterward, later, although we all did either good or even better. So… Vidas: So the competition went in 3 levels, right? For the 10th grade, 11th grade, and the 12th grade. And then you prepared a set of exercises for each grade, right, Ausra? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: And was it too difficult for, let’s say, 10th graders? Ausra: Actually no...I think it was still okay, and for 11th graders too. But for the 12th graders, those were especially hard, to sing. Vidas: Very chromatic and lots of modulations. Ausra: Mhm. Vidas: I see. Do you think that people would...Would people be able to play with their feet in a slow tempo, successfully? Ausra: Yes, I think so. Vidas: Those exercises that we converted into the 10-day Pedal Playing Challenge? Excellent. So guys, try it out. Of course we recommend extremely slow tempo. Do you think, Ausra, they could play it just once, or practice repeatedly? Ausra: Well, of course you could practice repeatedly. Vidas: Why? Ausra: Because it’s more beneficial. You could get more out of it. Vidas: Like etudes, right? Ausra: Sure. Vidas: And then, maybe one exercise per day. But some people need more days for one exercise, don’t you think? Ausra: Of course. Vidas: Like, up to 1 week, maybe? Ausra: Yes, or even a month. I don’t know, it depends on the person. Vidas: It doesn’t matter, actually, how much time you spend; it’s important just that you spend quality time, right? And you master each exercise to your satisfaction, that you feel that you’re progressing, right? Ausra: Yes, that’s true. Vidas: Excellent. So, please, guys, send us more of your questions; we love helping you grow. And send us your feedback about this course, right? And remember to transpose it one octave or two octaves down, because you will be playing it from the treble clef. Thank you, guys! This was Vidas. Ausra: And Ausra. Vidas: And remember, when you practice… Ausra: Miracles happen. |

DON'T MISS A THING! FREE UPDATES BY EMAIL.Thank you!You have successfully joined our subscriber list.  Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas

Authors

Drs. Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene Organists of Vilnius University , creators of Secrets of Organ Playing. Our Hauptwerk Setup:

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

This site participates in the Amazon, Thomann and other affiliate programs, the proceeds of which keep it free for anyone to read.

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed