|

Vidas: Hello and welcome to Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast!

Ausra: This is a show dedicated to helping you become a better organist. V: We’re your hosts Vidas Pinkevicius... A: ...and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene. V: We have over 25 years of experience of playing the organ A: ...and we’ve been teaching thousands of organists online from 89 countries since 2011. V: So now let’s jump in and get started with the podcast for today. A: We hope you’ll enjoy it! V: Hi guys! This is Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 637 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Sally, and she writes, "Do you have a secret to playing melody in the left hand and harmonies in RH? I have a hard time with that. My brain doesn’t want to allow LH to take the melody, at least not for long." V: Do you know what she’s talking about, Ausra? A: Yes. I can guess probably she’s right-handed as I am and you are, and she has the same trouble as many beginner organists have. And not only beginner. V; Sally is our Patreon supporter and she recently watched my Advent hymn improvisation recital. And in a lot of hymns, I place a tune in the left hand part instead of the right hand part. And if I want to play in the tenor range, then I play the melody in the tenor range with the left hand. But if I want to place it in the soprano, I could effectively cross my hands with the left hand playing high. I’ve seen Dutch organists do that and it fascinated me, this technique. Instead of switching hands, soprano in the right hand and accompanying voices in the left hand, they do soprano in the left hand but the higher range, you see? A: Well, I just feel sorry that you have been born in Lithuania and not in Netherlands. Lately you are so much impressed by what Dutch organists do, that I wish you could stay there and learn from them. V: I started to understand Dutch a little bit. It’s a little bit similar to German, and a little bit to English, too. So, when they’re talking about organs it’s not that hard to understand. A: Well, okay. So what could we suggest to Sally? One of my suggestions would be, maybe when she accompanies hymns, she could play the melody in the left hand, and accompany with the right hand and pedals. V: Yes, exactly. So play the tune in the tenor range, right, on the solo registration - trumpet, let’s say. A: Yes, so you need to basically to have at least two manuals in order to do that. V: Yes. Do you recommend crossing voices at the beginning? A: No, I wouldn’t suggest that. It might be really too difficult. V: Not even voice crossing, but hand crossing, when left hand goes beyond right hand. A: I wouldn’t do that at the beginning. V: Yeah, it’s probably too difficult. And I wrote to her that it was difficult for me at first, and even today sometimes I struggle and it’s not that easy. But you just have to keep playing, Keep practicing, and sooner or later something will switch in your brain, right? A: Yes, and if you want to have a real challenge and if you like music of J.S. Bach, I would suggest for you to work on An Wasserflüssen Babylon from the Leipzig Collection, or also called Great 18 Collection. It has this beautiful chorale with ornamented tenor in the left hand. Just as pretty as, for example, Nun komm der Heiden Heiland (video), or Schmücke dich, O Liebe Seele, but instead of having ornamented chorale in the right hand as in these two pieces mentioned, here in An Wasserflüssen Babylon, Bach writes down for the left hand, it’s ornamented cantus firmus, really beautiful. V: And you can make it more complex by playing double pedal lines. Five voices, right? For hymns, I think. A: Yes, because I wouldn’t do this in this chorale. V: But hasn’t Bach written double pedal version? A: Yes, but it doesn’t have the melody in the left hand so it doesn’t count. At least not in this case. V: Mm hm. Right. Right. So you have to just keep doing, keep expanding your tonal vocabulary, and when you place the melody in the left hand, right, so what becomes in your right hand, you’re playing alto and tenor. But alto in your own place, but tenor is one octave higher, right? A: Yes, usually that’s what you do when you switch voices. Soprano substitutes tenor and vice versa. V: So maybe if you’re a beginner at this and you struggle with placing melody in the left hand, maybe you don’t need to play all four parts right away, right? What about just playing tenor line, single tenor line, one octave higher with the right hand? And then soprano line one octave lower, both voices together - those two voices only in your hand. Do one voice, solo voice practice, then two voice combinations, three voice combinations, four part combinations finally. Just like a small organ piece. What do you say, Ausra? A: Yes, I think that might work. V: So try 15 combinations in four part texture. And if you do that, you can master any type of hymn, either with the melody in the right hand, or in the left hand, or even in the pedals. How would you do in the pedals, Ausra? If the melody is in the pedals? A: Yes, you could do that, but you have of course to register accordingly. V: But would you use the same harmonies, or you have to reharmonize? A: Well, you - of course it will still be same harmonies, same chords, but maybe different inversions. V: Different inversions because if you have let’s say in the melody, 2nd scale degree, you can play the dominant chord, right? But if the 2nd scale degree is in the pedals, you no longer have the dominant root position chord, but you have 6/4 chord, 2nd inversion, right? A: Or dominant 4/3 chord. V: Or 4/3. And then 4/3 is allowed, but 6/4 is allowed very in specific cases only. A: Yes. V: And therefore it’s better to leave it for more advanced users. So, instead of playing dominant 6/4 chord, you can effectively play 7th scale degree first inversion chord. In C Major, not DGB, but DFB. Make sense? A: Yes, makes sense - I’m teaching harmony (laughs). V: Good - good for you. Harmony never hurts. So, good luck Sally! Good luck whoever is harmonizing melodies in the left hand part. This is really fun. And it is complex at first if you haven’t done this before. And pay attention to what Ausra suggests. Play some pieces with the melody in the left hand part, right? This texture has to become less foreign to you. And this way, you will sort of remember those new positions in your hand. A: Yes, and if you’re playing piano, if you love piano repertoire, I just remembered one piece I played many years ago. It was called Melody by Sergei Rachmaninoff. It’s sort of not too difficult piece, but not at beginner level. I would say somewhere in the middle. It has the melody in the left hand, and accompaniment in the right hand, and left hand always crosses the right hand. It jumps back and forth from the bass to the soprano range, and it also helps to sort of make your left hand more independent. V: Good advice. So please send us more of your questions. We love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice, A: Miracles happen. V: This podcast is supported by Total Organist - the most comprehensive organ training program online. A: It has hundreds of courses, coaching and practice materials for every area of organ playing, thousands of instructional videos and PDF's. You will NOT find more value anywhere else online... V: Total Organist helps you to master any piece, perfect your technique, develop your sight-reading skills, and improvise or compose your own music and much much more… A: Sign up and begin your training today at organduo.lt and click on Total Organist. And of course, you will get the 1st month free too. You can cancel anytime. V: If you like our organ music, you can also support us on Patreon and get free CD’s. A: Find out more at patreon.com/secretsoforganplaying

Comments

Vidas: Hello and welcome to Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast!

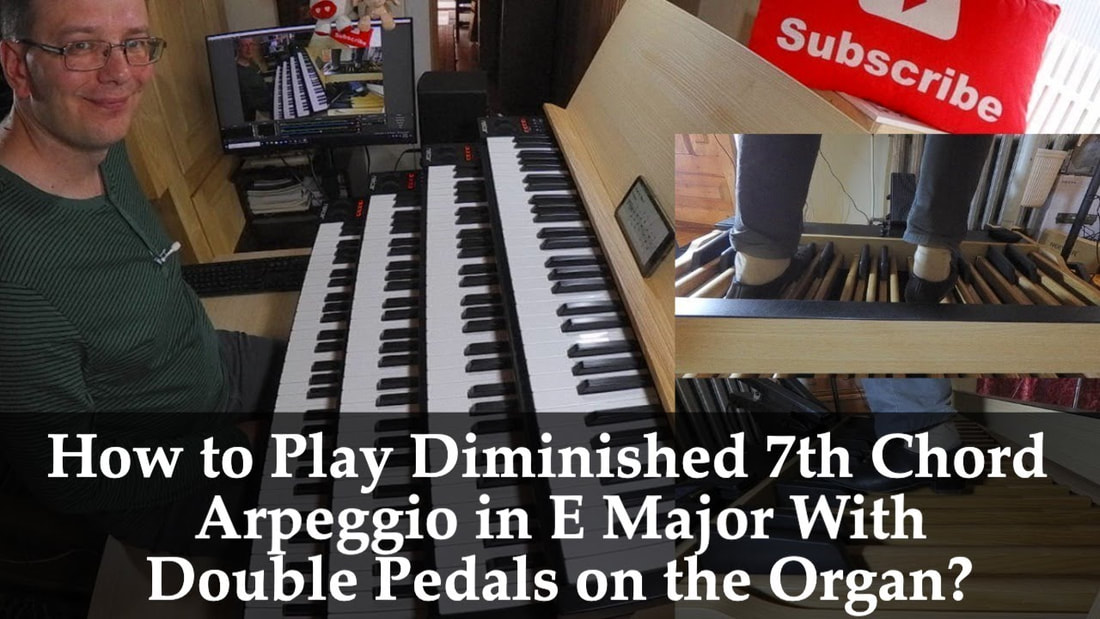

Ausra: This is a show dedicated to helping you become a better organist. V: We’re your hosts Vidas Pinkevicius... A: ...and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene. V: We have over 25 years of experience of playing the organ A: ...and we’ve been teaching thousands of organists online from 89 countries since 2011. V: So now let’s jump in and get started with the podcast for today. A: We hope you’ll enjoy it! V: Hi guys! This is Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 613 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Robert, and he is a student of Pedal Virtuoso Master Course. And he has a question which sounds like this, Dear Vidas, I just finished the tenth week of your Pedal Virtuoso Master Class. Unlike previous weeks when I come to the last day, I still have issues maintaining a proper sense of balance while seated on the organ bench. This affects my accuracy (I either hit an extra pedal in one foot, miss a pedal, or slide off the correct pedal and into a non chord tone), playing legato (sometimes a major third in one foot is not possible to connect), and playing the pedals silently (as opposed to making a too much noise). Regarding balance, I found in all the previous weeks that I could sit quietly on the bench and avoid having to pull myself back to my normal seated position by shifting my weight from one hip and buttocks to the other. This week, perhaps due to the fact that an octave arpeggio in octaves covers too much space on the pedals in such a short amount of time as well as the fact that two feet moving at the same time reduces the body’s range of motion, playing an arpeggio this week with confidence was not possible. My appearance on the bench was too active as I had to keep adjusting myself when my body would move closer and closer to the console as a result of twisting my body in order to reach pedals. For some of the arpeggios, like B Minor, E Major, and D Minor, not moving on the bench put too much of a strain on my legs and feet that in the end did not enable me to reach the desired pedal in one foot (and occasionally pedals in both feet) with confidence. My remedy this week has been to shift my weight a little bit, however, a precise note to shift on (unlike scales and all previous arpeggios) or even which direction to shift into (left or right side) has not been possible for me to determine. These problems occur when I am playing very slowly in rhythm. Faster tempos are not possible this week. Feel free to contact me. Thank you for your time and thank you very much for designing a wonderful course as well as sharing your knowledge with me and every other organist. Sincerely, Robert V: And does it make sense, Ausra, what he’s talking about? Playing arpeggios in double octaves, very difficult to maintain balance. A: Yes, it is very difficult. And I think when you have such a difficult exercise or a spot in a real organ piece, I think you might not be following rules so strictly and you might move a little bit more to help yourself to make it possible. Because other way, I’m afraid you might injure your back or your legs. What do you think about it, Vidas? V: Sure. I think at first I wrote him a message that he doesn't have to worry too much about playing in perfect legato fashion or in a faster tempo these difficult exercises, because scales and arpeggios are not the end in itself, right? We rarely find a piece of music which has all the scales and arpeggios in it. It would be artificial and unmusical. A: Sure. Plus I think when we are talking about arpeggios and fast passages, I think usually pieces with extremely difficult pedal part are written in a fast tempo, too. And often when you play in a really fast tempo, even if you won’t connect completely one note to another, it will still sound legato. And believe me, I know it. For example, now I’m thinking about Fugue in B Major, written by Marcel Dupre. You know that famous Three Preludes and Fugues, in B Major, in G Minor… V: The middle one is in F Minor. A: Yes, in F Minor. So I was playing the B Major Prelude and Fugue, and that Fugue really has a fast and complicated subject. And when it comes to the pedal and you still need to play it legato, it gives you a lot of trouble. But because the tempo is really fast, so even if sometimes you won’t play complete legato, as the final version it will still sound as legato. V: So, he wrote back to me that it still doesn’t help, this kind of explanation. And he would like to have my own video demonstration of, let’s say E Major double arpeggio over the tonic chord, and the diminished seventh chord double arpeggio. A: And you made a video, yes for him? V: I made two videos, yeah, for him but also for other people who are struggling with this. So I put it on YouTube, and I will share of course the link in this podcast as well for people to see. Of course, it’s an exception. It’s not a video course, yet. And it’s a PDF-based course, and video exercises don’t belong to this course. They are just extra. I have two other videos - how to play C Major scale, for example, or D Major scale. But they’re extra, bonuses basically, not a part of the material. So I demonstrated, but you have to understand that it’s not the goal in itself to play those exercises perfectly without any glitch, without any hesitation. The goal is to go through these exercises, repeat them let’s say 10 times in a slow tempo, each of them, and then after 3 months, go back to the difficult pedal passages that you were not able to play like 3 months before and check, check your progress to see if you have advanced further. And I can almost guarantee that you will if you are diligently practice every day those exercises for 3 months. It’s like Marcel Dupre was a teenager I think, and he cut one of his wrists badly in a glass, and for 3 months he couldn’t practice with his hands on the piano, so he practiced pedals on the organ, pedal scales and arpeggios. And he wrote in his memoirs that he practiced them with vengeance. And that’s how he became basically invincible in his pedal… A: Pedal virtuoso. V: Pedal virtuoso, yeah. And the secret to pedal technique, perfect pedal technique he wrote is the flexibility of an ankle. Now we might have various different opinions about Dupre and his methods and his let’s say accuracy of historical performance practice, or lack of accuracy, right when he fingers and pedals everything in legato with pedal and finger substitutions for the music of Bach, let’s say - this was his time. But we cannot deny that for his time, playing legato technique, he was a champion of it. And we can learn a thing or two from his method as well. So in this course, the Pedal Virtuoso Master Course, we have a series of exercises over 3 months, with pedal scales and arpeggios of various positions, and people could really benefit from that. But never forget that this is not the end. It’s just the means to the end, right? It’s just an exercise to help you develop this ankle flexibility which will help you perfect your pedal technique and play real organ music. A: So this is just a tool. V: Tool, yes, tool. And I would even, like Ausra said, don’t worry too much about obsessing about perfecting those exercises. You better spend like 15 minutes or half an hour at the most with them per day, and then do something else with your organ playing that day if you have time. Like playing real organ music, mastering harmony, maybe improvising. Things like that. Hymn playing also. And watch for not straining your legs, your ankles. It’s very important to warm up before playing scales and arpeggios. These are strenuous exercises. We have to emphasize that. A: That’s right. Especially if you are practicing early in the morning. V: Right. So, go ahead and watch those videos. These will be very helpful for people to see how I play them myself. And please send us more of your questions. We love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice, A: Miracles happen. V: This podcast is supported by Total Organist - the most comprehensive organ training program online. A: It has hundreds of courses, coaching and practice materials for every area of organ playing, thousands of instructional videos and PDF's. You will NOT find more value anywhere else online... V: Total Organist helps you to master any piece, perfect your technique, develop your sight-reading skills, and improvise or compose your own music and much much more… A: Sign up and begin your training today at organduo.lt and click on Total Organist. And of course, you will get the 1st month free too. You can cancel anytime. V: If you like our organ music, you can also support us on Patreon and get free CD’s. A: Find out more at patreon.com/secretsoforganplaying In this video I will show you how to play diminished 7th chord arpeggio over one octave with double pedals in E Major. Hope you will enjoy it! I will be playing Velesovo sample set by Sonus Paradisi of Hauptwerk VPO.

Pedal Virtuoso Master Course: https://secrets-of-organ-playing.mysh...

Total Organist and Secrets of Organ Playing Midsummer 50% Discount (until July 1).

Vidas: Hello and welcome to Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast! Ausra: This is a show dedicated to helping you become a better organist. V: We’re your hosts Vidas Pinkevicius... A: ...and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene. V: We have over 25 years of experience of playing the organ A: ...and we’ve been teaching thousands of organists online from 89 countries since 2011. V: So now let’s jump in and get started with the podcast for today. A: We hope you’ll enjoy it! V: Let’s start episode 598 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Vivien, and she writes: “Thank you so much for your acknowledgment and interest Vidas. Next time I will understand better how to enter the amount of money and make it more in line with the quantity and quality of expert help coming from you and Ausra. Lockdown means no Church Services and so has given me a chance to improve my basic skills instead of being stressed with deadlines. I’m trying to improve my trills and am using a manual piece Jesus, meine Zuversicht, BWV 728. I listen to Wolfgang Stockmeier because I happen to have his CDs, copy him and then record myself. The long trills still sound awkward, but then I found your advice of slow, exact and emphasising every other note which I’ve never read before. Feeling optimistic that this could be a breakthrough. Can’t believe the way that you understand such detailed problems. I hope that you both are coping well in this crisis. Best Regards Vivien” V: So, Ausra, what comes to mind when you read this message? A: I remember my way of dealing with trills, actually. V: And? Was it a long time ago? A: Yes, it was a long time ago, but actually I struggled with playing trills well for quite a long time, and I think what I had was not so much as a physical incapacity to play them right, but something in my head that I was so much afraid of trills that when the trill would come, I would get like a muscle spasm or something and couldn’t execute them right. V: In long trills, you mean? Or short ones? A: Yes, usually in longer. The longer the trill, the bigger the problem was. V: For me, the pedal trills are quite complex, or actually I should say was quite complex. Remember the B-A-C-H by Liszt, “Prelude and Fugue on B-A-C-H,” and there is this pedal trill toward the end, a long one, and expanding to the next measure and the next measure… A: Yes, I remember this piece, it’s fun! V: ...in the last measure, in the last page, I think… I was struggling with it for a long time. A: That’s funny because, you know, this was one of the easiest pieces that I have played that sounds really hard. I don’t know.. I learned it very fast, and it gave me none of the technical difficulties. V: Even in the pedals? A: Yes, even in the pedals, because you don’t have to play like double trills to play a trill with one foot, you just use both of your feet, and that’s it! V: I don’t remember if it’s a double trill in octaves or not. A: No. V: No. You know what? I always admired your ability to play long trills with 3-4-3-4-3-4 fingers. A: Yes, but I only can do it on a tracker action, because on our Hauptwerk, on the plastic keyboard I cannot do it. I use the 2-3, 3-2. V: What’s your secret then, in playing trills? A: Actually, what helped me to overcome those spasms was breathing. Basically, I just have to breathe. Don’t forget to breathe before the trill and during the trill, especially if it’s a long one, and somehow it relaxes my muscles and I can play it successfully. Of course, another thing is that, well, you need to preserve the rhythmical structure of the piece, because what happens often with the beginners is that when the trill comes, that they simply lose the sense of the rhythmical flow. So what I would do if I were a beginner is that I would learn a piece or at least play it a part of the way through without trills, just omitting them for a while. And then, when I would be really comfortable with the text, then I would add them. That would preserve the rhythmical structure and of course, another thing is, as you said to Vivien earlier, how you accent the trill in order to make it correct, but then another way would be to not play it so strictly rhythmically, because if you will play it in a final version and emphasize each other note, it will sound ridiculously unmusical. V: Yeah, it would sound artificial. A: Yes, so basically what I do with my long trills is that I start slowly, and I speed up, and then towards the end I slow down again. And then, it becomes more natural. V: Good violinists play like that in Baroque music, so it’s good to listen to violin trills and then copy them. Why didn’t you tell me about breathing when I was struggling with the B-A-C-H by Liszt trills? A: Well, it was such a long time ago that I don’t think I had developed my own technique at that time. V: Yeah. I wish I had known this advice earlier. A: It helps for hand trills. I don’t know if that would work for the pedal. V: Probably still! Everything tenses up when you stop breathing. Your ankles, too. Yeah, probably would help. So guys, keep breathing when you’re playing trills, and practice, of course, slowly at first. Vivien doesn’t make a mistake here with practicing slowly at first, when you’re just first getting the hang of the trill, but when it’s more naturally to you, then you can apply Ausra’s advice, too. A: Plus try different fingerings sometimes. I would not suggest you to try the fifth and the fourth finger because it probably wouldn’t work, maybe for you it would, but try the fourth and three; for some people it works, like for me on the tracker organ. If that doesn’t work, then try 3-2. Actually, try 3-1! This works sometimes quite nicely, because it’s sort of a natural hand position. And even for some people 1-2 might work, so it’s according to each of our individual natures. So try all these combinations and see what works best for you. V: I even in some piano exercise, I think it was… it might have been Hanon drills doing it like this: 1-3-2-3-1-3-2-3-1-3-2-3, like this. A: Yes, it makes sense sometimes! V: It’s a romantic technique, not necessarily Baroque. But if you’re playing later music, why not? Of course later music doesn’t have as many trills! A: That’s right! And another suggestion, if absolutely some of the trills don’t work for you and you can’t play them gracefully, then just omit them in your final performance, because really, the trill that is not executed nicely can ruin an entire piece. V: I agree. A: So it’s better to do less ornamentation than to do it in a not graceful manner. V: While we are talking about this, would you recommend people starting include ornamentation right at the beginning of the learning process, or somewhere in the middle? A: Well, it depends on how much you struggle with it, because for people for whom trills ruin the rhythmical structure of the piece, I would suggest to learn to play, to practice the piece from the beginning without any ornaments. If it’s not an issue, then you can add ornaments right away. V: Yeah, in music schools, teachers usually omit the trills for a quite some time so students don’t get used to them, and then they struggle while adding them just in the final month or so. A: That’s in general. Pianists, most of the time they don’t know how to play the ornaments, because they don’t deal so much with the Baroque music, so they are not as good at reading trills as the organists are. V: Yeah, and a good table of ornaments if you’re playing music of J. S. Bach is the beginning of his “Klavierbüchlein für Wilhelm Friedmann Bach.” He copied, I think, the Frenchman’s d’Anglebert's table of ornaments there. So that’s why we use the French style of ornamentation. A: But again, you know, if you are playing other composers, such as Buxtehude, for example, then you have to follow with the Italian way of ornamenting. V: Yes, starting from the main note, not from the upper note. But there are exceptions, of course. So many things to talk about. Maybe we will leave it for future conversations. Thank you guys, this was Vidas, A: And Ausra! V: Please send us more of your questions; we love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice, A: Miracles happen. V: This podcast is supported by Total Organist - the most comprehensive organ training program online. A: It has hundreds of courses, coaching and practice materials for every area of organ playing, thousands of instructional videos and PDF's. You will NOT find more value anywhere else online... V: Total Organist helps you to master any piece, perfect your technique, develop your sight-reading skills, and improvise or compose your own music and much much more… A: Sign up and begin your training today at organduo.lt and click on Total Organist. And of course, you will get the 1st month free too. You can cancel anytime. V: If you like our organ music, you can also support us on Patreon and get free CD’s. A: Find out more at patreon.com/secretsoforganplaying Total Organist and Secrets of Organ Playing Midsummer 50% Discount (until July 1).

Vidas: Hello and welcome to Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast!

Ausra: This is a show dedicated to helping you become a better organist. V: We’re your hosts Vidas Pinkevicius... A: ...and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene. V: We have over 25 years of experience of playing the organ A: ...and we’ve been teaching thousands of organists online from 89 countries since 2011. V: So now let’s jump in and get started with the podcast for today. A: We hope you’ll enjoy it! V: Hi guys! This is Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 599 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by María de Jesús Redentor. And Maria writes, Good evening, Vidas. My goal in learning to play the organ is to play during the liturgical celebrations and I would like to focus on that. In addition, I would like to get to know the organ registration, as well as improvisation and improvised accompaniment, and also the possibility of performing pieces, especially in the Baroque and Classicist style. My obstacles are: 1) I am a beginner organist and I do not have much practice. 2) Because of my personal situation I do not have a lot of time to exercise and I cannot commit myself to systematic and conscientious exercise. 3) What I want to add is that I still have difficulty in performing typical organ pieces with a pedal. Using the opportunity, I would like to thank you very much for this possibility to learn playing the organ online and for very practical and helpful instructions. María de Jesús Redentor V: She wants to play in church services, basically. A: Yes, yes. That's what I understood from her letter. V: So Maria first needs to overcome her obstacles, obviously. She's a beginner, and maybe that's natural to have less experience than more advanced organists, don’t you think? A: Yes. And I don't think that this is the main problem, not having experience. You can gain experience by practicing diligently on a regular basis. I think that not finding time to practice, it’s a bigger problem. V: Mm hm. A: Because, you know, nothing comes without hard work. You have to do it on a regular basis. Especially, you know, if she writes that she still struggles with pedal technique. I think it all comes from the lack of practice. V: My mom always used to say, “Art requires sacrifice.” Remember that saying? A: Yes. I remember that. V: Do you remember the context in which she would say that? A: I remember you telling me, but maybe it doesn’t work, doesn’t apply to this situation. V: (laughs) Maybe, but I just tell you because it's funny. My mom would, she's a graphic artist, and when she was a student, she would try to catch butterflies, and I think make them into, what, what’s this word, you know, like an exposition of butterflies. And she would say, “Art requires sacrifice.” (laughs) A: So basically she would hunt and kill the butterflies. V: Yes. A: How cruel your mom was. V: (laughs) She was very sorry afterwards. Yeah. So in this case, art requires exercise - not exercise - and exercise, too, but also sacrifice. From Maria’s part. A: So basically, you have to find time to practice on a regular basis. Because otherwise, your progress, you would still progress if you would practice, let’s say twice or three times a week. But it would be really slow. V: I don't think she can find time. No, it's impossible. I think she has to make time. And that's a big difference, right? If you look at your schedule, which is really busy in Maria's case perhaps, and she doesn't have any opening, doesn’t see any opening, and she says, Never mind - no, this day I cannot practice, right? A: Well, then my suggestion would be, sleep less! V: But she has to make time by prioritizing her activities. What’s the most important thing in her activities? And do that first. If organ is not as important, then it will be left for evening when she is too tired to do anything probably, right? A: It depends on what kind of personality she is. If she is the early bird or late bird, so. V: Mm hm. A: It depends. I do most of my important things in the morning. V: Me, too. Me, too. Creative stuff has to be done in the morning, in my opinion. And more managerial stuff can be left for the afternoon. Like replying to emails, doing some management work, which doesn’t require your creative so much. A: Well, and because Maria wants to be a church organist, to play for liturgy, and usually, organists, for playing the liturgy, we get paid. V: Yes. A: In most of the cases, yes? Then maybe this could be also a good stimulus to practice more and become a better organist. V: Like motivation. A: And maybe eventually to get more paid for it. V: Mm hm. That’s right. If you play with pedals, you get paid less, or more? A: More, I would say. V: If you play with one foot you would get paid less or more than with two feet? A: Well, I guess answer is obvious. V: (laughs) Good. So guys, apply this in your practice. And Maria, too. Our advice really works, people tell us, right Ausra? A: Yes. V: But you have to be strict with yourself. You have to be honest with yourself. And don't make excuses. Because art requires sacrifice. A: True. And just see what consumes most of the time, because I'm sure it's either computer or TV or smartphone, or something. V: Yeah. Maybe delete all apps. All social networking apps on your phone. Check Facebook only from your computer, not from your phone. Then you will have plenty of time, right? Because all those notifications, Facebook is very very intrusive into your life, and very very smart marketing company policy - they’ll allow you to only temporarily delete those notifications on your phone. After a day or so, they will come back. And you will be distracted again, right, Ausra? A: That’s right. V: But people like to be distracted, that’s the problem. A: True. V: It’s easier to get distracted than to actually get some work done. Okay, guys - Please send us more of your questions. We love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice, A: Miracles happen. V: This podcast is supported by Total Organist - the most comprehensive organ training program online. A: It has hundreds of courses, coaching and practice materials for every area of organ playing, thousands of instructional videos and PDF's. You will NOT find more value anywhere else online... V: Total Organist helps you to master any piece, perfect your technique, develop your sight-reading skills, and improvise or compose your own music and much much more… A: Sign up and begin your training today at organduo.lt and click on Total Organist. And of course, you will get the 1st month free too. You can cancel anytime. V: If you like our organ music, you can also support us on Patreon and get free CD’s. A: Find out more at patreon.com/secretsoforganplaying

Vidas: Hello and welcome to Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast!

Ausra: This is a show dedicated to helping you become a better organist. V: We’re your hosts Vidas Pinkevicius... A: ...and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene. V: We have over 25 years of experience of playing the organ A: ...and we’ve been teaching thousands of organists online from 89 countries since 2011. V: So now let’s jump in and get started with the podcast for today. A: We hope you’ll enjoy it! V: Hi guys! This is Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 597 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Bill. And he writes, I put in 15-30 minutes a day working on the sight reading course. I've been working on BWV 543 Bach Prelude & Fugue in A Minor mostly beyond that. Two things that frustrate me are it takes me about 3 months to learn these big fugues (practicing about 1.5 hours/day) and the playing the strings of 32nd notes evenly at high tempo. Any suggestions to speed up learning and play better at high tempos would be appreciated. I do like the sight reading course, it certainly has me reading better! Regards, Bill V: So, Ausra, do you wonder why Bill is struggling with BWV 543 so much? A: Well, you know, it’s one of the major pieces by J.S. Bach, and my suggestion would be, if it takes for you 3 months to learn such a piece and you still struggle playing 32nds in the fast tempo right, it means that actually this piece is actually too hard for you, for right now. If I would be you, I would go back to an easier repertoire. Make sure you have played all 2 part and 3 part inventions, you have done some of the Well Tempered Clavier, you have played all 8 Preludes, Small, Little Preludes and Fugues by J.S. Bach, and even then, after starting working on a major prelude and fugue by J.S. Bach, A Minor is probably not the easiest out of them. Definitely there are easier ones. V: I should also add that you have to define what kind of level you should be when you take the new piece. I have to say, what kind of, you have to master the piece, and what does it mean, right? You have to be able to perform it for others, and then go to the next piece. A: That’s right. V: If you don’t want to share your work online with strangers, that’s fine. But please play it at least for your friends and family. You learn a piece, and you show them what you’ve learned. A: Because, you know, for the piece like this A Minor, I guess if you are at the right level to play such kind of difficulty of piece, you need to be able to do text of it, roughly in a month. If it takes you longer, it means that this piece is still too hard for you. V: You say you learned entire Clavierübung III by Bach, in a month. A: Yes. That’s what I did. But it was when I was in good shape, at the full potential of my capacity, so… V: Capacity. A: Capacity, yes. V: Was your professor George Ritchie surprised? A: Yes. V: He wouldn’t learn so fast? A: Well, I don’t know. Maybe he would learn it, I don’t know, but really I think I was getting to him sometimes at my learning tempos. V: Mm hm. Yeah, that’s right. Did you have good sight reading abilities at the time? A: Yes I did have. But you know...it’s...usually people take it for granted - if you are a good sight reader, you can learn music fast. It’s not true. I was always a really good sight reader. But usually when I play the same piece the second time or the third time, I would make more mistakes than just sight reading it. V: I can see why, because you lose concentration, yes? A: Yes. V: The first time might be the best. A: Yes, that’s how it works for me. V: Mm hm. Maybe you should try sight reading short recital! A: (laughs) Maybe not. V: Like easier pieces, and see how it goes. I did that once with 8 Little Preludes and Fugues, BWV 553-560 and it went okay. It went without major mistakes. But the feeling for me wasn’t very nice. I wasn’t relaxed. A: Well, it wasn’t true sight reading. Because you had played those pieces many, many years ago. V: Mm hm. A: And then you sort of re-sight read them again. V: Exactly, yes. A: So it’s not the same. I’m talking about… V: Completely… A: Completely new. V: I see. When you learned to sight read on the organ, did you use my sight reading master course? A: No. V: Of course not. A: It wasn’t ready at that time. V: It’s a dumb question, right? A: Yes, it is. V: And I mean that, you learned, you taught yourself just by playing repertoire. A: Yes, that’s right. V: Much repertoire. The more, the better. So I think Bill will also get better at sight reading with our sight reading course, this will be more systematic than just simply sight reading whatever you want. But Ausra says very wise suggestion: to take and learn easier repertoire first. There is on American Guild of Organist website a list of graded repertoire. For Bach music, for Langlais music, for Messiaen, for music composed after Bach in Germany. And you can see which level A Minor Prelude and Fugue belongs to. It certainly is not at the beginning and probably not even in the middle. This graded repertoire list has 10 levels. So it might be maybe level 10 or 9 or 8, something like that. So pick something from earlier levels first, right? A: Yes. Because I think that playing music, any kind of music, has to give you some kind, some sort of pleasure. And if you are playing too hard pieces that are too hard for you at that moment, you might get frustrated and disappointed. V: That’s right. And take the time to learn each piece really well. I recommend recording yourself, even if you don't show it to anybody else. Because this, knowing that you only have one chance to play through a piece without any stops. Because you know that the recording is going makes you focus much better. A: True. And you know why I'm not arguing for you to, not encouraging you to play too hard pieces. Because I know for myself, when I was at the second grade at the academy for music, at the beginning of my second year of playing organ at all, my teacher gave me to play the B Minor Prelude and Fugue, BWV 544 by J.S. Bach. And as you well know, it is one of the most complex Preludes and fugues by J.S. Bach. V: Which level, which year was that? A: Beginning of the second year. V: Wow. A: Of playing the organ. And… V: And you wonder why my teacher gave me the A Minor at the 12th grade? A: I struggled so much just to learn that music, you know? And I did it like in 2 months, but it took me such a pain, and so many hours. I put so much effort into it. I finally played it for an exam, but it never gave me any pleasure, and I never went back to this piece. Never in my life. And probably will never will. And even now, when I now listen to other organists playing this piece, I’m having this very sort of uneasy, unpleasant feeling. So basically, that teacher just ruined me this B minor piece forever. V: Young teachers are like this. They imagine things much more differently than experienced teacher would, right? But I guarantee that if you took up this piece right now, it wouldn't be a problem for you at all right now, probably. You would just slowly sight read it very comfortably. A: Yes, but I’m not willing to do it. V: Yeah. So guys, please send us more of your questions. We love helping you grow. This was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: And remember, when you practice A: Miracles happen. V: This podcast is supported by Total Organist - the most comprehensive organ training program online. A: It has hundreds of courses, coaching and practice materials for every area of organ playing, thousands of instructional videos and PDF's. You will NOT find more value anywhere else online... V: Total Organist helps you to master any piece, perfect your technique, develop your sight-reading skills, and improvise or compose your own music and much much more… A: Sign up and begin your training today at organduo.lt and click on Total Organist. And of course, you will get the 1st month free too. You can cancel anytime. V: If you like our organ music, you can also support us on Patreon and get free CD’s. A: Find out more at patreon.com/secretsoforganplaying

Vidas: Hello and welcome to Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast!

Ausra: This is a show dedicated to helping you become a better organist. V: We’re your hosts Vidas Pinkevicius... A: ...and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene. V: We have over 25 years of experience of playing the organ A: ...and we’ve been teaching thousands of organists online from 89 countries since 2011. V: So now let’s jump in and get started with the podcast for today. A: We hope you’ll enjoy it! V: Hi guys, this is Vidas! A: And Ausra! V: Let’s start episode 584 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by John, and he writes: “I'm wondering if you could help with selecting the next piece I should learn, and give a ranking to the difficulty of these pieces. As you know I'm at a beginner/intermediate level, there's no way I can tackle a large Bach fugue. I know I should learn some French repertoire, but that is also a challenge with finger technique and playing fast passages. Let me know what you think. - BWV 547 Prelude in C major (Prelude only) - BWV 546 Prelude in C minor (Prelude only) - BWV 578 The Little Fugue in G minor - Fanfare by Lemmens - Noel X by Daquin Feel free to suggest any other pieces I should have in my next wish list! I am also hoping to spend some time preparing a basic composition or improvisation for Easter, perhaps on the Hymn tune ‘Christ the Lord is risen today’.” V: So, John from Australia is back with this question. Ausra, what do you think? 547 is this 9/8 “C Major Prelude,” a very difficult one. A: Yes, it’s a difficult one. I would not start, probably, working on that right away. V: 546 is C is “C Minor Prelude and Fugue,” probably also too difficult. It’s at the advanced level. 577, the “Gigue Fugue.” Oh, but he writes… 577 is the “Gigue Fugue,” but he writes the title as “The Little Fugue in G minor, which is actually 578. A: I think this might work, probably! V: Yes, 578 would work. A: I think. Out of these three pieces by Bach, I would say that “This Little Fugue in G Minor” is the most manageable. V: Yes. And of course, Lemmen’s “Fanfare” would work well, “Noel X” would work by Daquin, right? A: Yes, if you have good finger technique, because it’s very playful! All these Noels by Daquin. The easy part is that they don’t have the pedal part, but the hard thing is all that French ornamentation, which is so rich and varied, and of course fast tempo. V: That’s right. What can we suggest he could learn in addition to Bach, Lemmens and Daquin? Maybe some 20th Century music or 21st Century music, right? A: If he likes it, because not everybody likes contemporary music or 20th Century music. V: It depends on his occasion, of course—he is a liturgical organist, and in this question, he was preparing for Easter. As we are recording this podcast episode, we have passed Easter by a couple of weeks, and of course he has to look for other festivities, maybe Pentecost, right? A: Yes, I think this is the one that is coming. V: Maybe “Veni Creator” of some kind? A: Sure, why not? And if he is really interested in French music, let’s say French Baroque music, maybe, he could look at the “Veni Creator” by De Grigny V: Nicolas de Grigny! A: It’s gorgeous! It’s very nice. V: Do you think he could do it? A: Well, probably, yes. Maybe not the entire set, but… V: some parts A: Yes, some parts V: of the suites. A: And it’s a wonderful piece, because if he would learn it, especially the opening section and the closing one, they are very well fitted, not only for Pentecost, but also for weddings! Because I don’t know how the Protestant churches do, but let’s say Catholics, they always sing this hymn to the Holy Ghost during the wedding ceremony. V: In the beginning! A: Yes, which is, of course, “Veni Creator.” So, I guess this would work very well, and I have played it myself for many, many weddings in the past, and nobody complained. V: Nobody complained, yet! A: Yes. But of course, if we are talking about Veni Creator, there are so many sets, so many compositions based on it. V: Even I wrote two. A: Yes, and I played one of them, so… and of course, the famous Duruflé variations, Prelude, Adagio, and Variations on Veni Creator. V: Johann Sebastian Bach wrote a few Chorale Preludes based on this Lutheran version of the same Chorale. A: Komm Heiliger Geist, yes. V: Yes. And Dieterich Buxtehude wrote the same thing. A: You know, when John asked about repertoire and he named these big pieces by J. S. Bach, I thought if he doesn’t feel like he’s ready to play a fugue by J. S. Bach, maybe he needs to play some free works by Dieterich Buxtehude, because I think his free works are easier than Bach’s, but still really substantial works, and it’s a good preparation for Bach’s music. V: And you’re saying this from your own experience now! A: Why now? I always knew Buxtehude! V: But especially now, because you are in the middle of recording Buxtehude’s works! A: Well, I’m at the beginning of it. Let’s face it, there are like five volumes and I am just doing the first volume right now. V: Yes. A: But yes, if I will not fail, I might complete it in a year or so. V: Wonderful pieces. I can hear them first hand. Your recording sessions… very colorful music. A: So, and there are all kinds of Praeludium by Buxtehude, which also has this Stylus Phantasticus, famous for Northern Germans, where you have these free episodes alternating with sort of strictly counterpuntal episodes, sort of like fugal sections, but not as complicated as Bach’s fugues. They are shorter and easier. V: Of course there are Passacaglia, Chaconnes… A: Yes, and you know the Passacaglia is easier, because you have the same melody in the pedal all over again and again and again, so you don’t have to think so much about pedals, and it’s beautiful! Extremely beautiful. V: This could be a starting composition for anybody who is interested in Buxtehude’s free works, right? A: Yes, I think it’s very nice. V: Because, not too many pedals, but the style by Buxtehude I think also is quite lively, but maybe moderately lively, and it’s a very famous piece, too! A: Sure, and I’m sure that Bach knew it, because you can hear some remnants of it in Bach’s Passacaglia. V: Yes, Bach’s Passacaglia has its own structure, nevertheless Buxtehude’s Passacaglia has four sections, and each of those sections are written in different keys: Tonic, third degree key, then dominant key, and then back to tonic, and each of those sections have seven variations each. And some scientists believe the number seven represents, back in the day as known, seven planets, so maybe cosmological significance. A: But anyway, it’s a wonderful piece, too, I thought. V: Wonderful. I should do the fingering and pedaling for this piece definitely in the future for people who are interested in learning it. So guys, please send us more of your questions, we love helping you grow. This was Vidas, A: And Ausra! V: And remember; when you practice, A: Miracles happen. V: This podcast is supported by Total Organist - the most comprehensive organ training program online. A: It has hundreds of courses, coaching and practice materials for every area of organ playing, thousands of instructional videos and PDF's. You will NOT find more value anywhere else online... V: Total Organist helps you to master any piece, perfect your technique, develop your sight-reading skills, and improvise or compose your own music and much much more… A: Sign up and begin your training today at organduo.lt and click on Total Organist. And of course, you will get the 1st month free too. You can cancel anytime. V: If you like our organ music, you can also support us on Patreon and get free CD’s. A: Find out more at patreon.com/secretsoforganplaying

Vidas: Hi, guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra V: Let’s start episode 550, of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by John. And he writes: I believe you and Ausra would have had quite a bit of experience organizing the church music program in the US, including choirs? Would be great to learn some tips from you guys! I would enjoy getting some advice from you on keyboard technique and finger accuracy. V: How should we start, Ausra? A: Well, I guess, yes, we have some experience organizing church music in America. But concerning choirs, I would say we have more experience organizing church music in Lithuania. Because before leaving to the United States we worked with two choirs in St. Johns church in Vilnius. V: Yes, and in America we were organists, not… A: Yes. V: music directors. A: So… V: In Lithuania, if you want to lead the choir and direct the musical life within the parish, within your congregation, you needed to be in charge, not only of the choir, not only of choir rehearsals, but also think about what musical activities you want to do between Sundays. A: Yes. And if we are talking about our choir groups in Lithuania that we had before going to the states, we had two choirs; one was a choir where mostly professionals sang, or at least people who had some professional musical education. And we sang, well, early music mostly. And I mean really early music, like Renaissance polyphony. V: We even early sang the earliest surviving polyphonic Requiem which is by Johannes Ockeghem. A: Yes and we also sang some masses of Jacob Obrecht and other nice Renaissance composers. And of course we did some Bach, Bach’s choral music as well. And it wasn’t very easy to keep this group because we were all, of them basically, almost professionals, or professional. And we asked them to come to church to sing each Sunday for free. But we, well, kept going it for a while, for quite a while. But of course when we left to the states, all this group disappeared. And another choir was the youth group. And they sang sort of easier music, like pop, pop, Christian pop music. V: Yes. A: With various instruments, with of course keyboards and guitars and I would play my recorder and we had little girl who would play some percussion. V: It was fun. A: Yes. And it we had some music that we brought with us from Austria. And actually I created the Lithuanian text for that music, so, we sang those. V: In general, if we are talking about directing choral life around your congregation, you need to satisfy three, sometimes conflicting sides—yourself, right, musically it has to be pleasing to yourself. If you are not doing the work you are proud of, I think you will not continue to do it after a while. A: Well, but you know, in this second choir we welcomed everybody who wanted to sing. And not everybody even had to know like good musical pitch. V: Mmm-hmm. A: So, and some would sing out of tune. But because in this second choir we had lots of members. V: Mmm-hmm. A: So we sang loud enough in order to diminish those who cannot sing well enough. V: But what I mean is we were able to do both choirs because we really loved early music at that time. We were able to reconcile two different styles, two different even skill set levels, advancement levels of those members because we really loved early music and we understood if we only sang early music with that, the first choir, we would never be able to satisfy what congregation needs and wants. A: Well, we did hymns too, of course, not... V: Yes, but for the second mass they wanted some light music, right? A: Yes, for youth. V: For youth. By the way, for the second mass right now, they have gospel music, another group, quite well know group in Vilnius. And we’re not in charge anymore of any choral activities in that church. We’re only in charge of organ activities within the university. So, so if John is thinking about leading a musical life, including choral life in his congregation, I think he needs to think about what he wants, what congregation wants, and what his choir members want, also. A: And what they can. V: Mmm-hmm. A: Because you might want to do it but you cannot have ability to do it. V: And you need to do sometimes, you sometimes have to meet them in the middle. If they want to do one thing and you want to do another thing, maybe you can agree to meet somewhere in the middle, like a compromise. That’s possible, if they’re open for compromises. Sometimes not. Sometimes they’re very direct and very specific about what they want. But I guess even in that situation, if you are forced to do something that you don’t want to do, maybe you have, you can have a corner of musical activity that you enjoy doing in that congregation. And because of the opportunity to rehearse with that ensemble for example, or, I don’t what John enjoys, maybe play organ music right? Maybe he can do something else as well, in addition to that, like a compromise, like a service for the congregation. But maybe I’m over exaggerating. Maybe he would enjoy doing all kinds of musical activities, and maybe that’s not a problem for him, right? A: Yeah, sure. V: So then, John was also asking about a couple of other things—advice about keyboard technique and finger accuracy. We could discuss this in another episode, right, because it’s kind of unrelated. A: Yes, unrelated to the first half of the question. V: Okay guys. So stay tuned for our next episode and we will discuss the rest of John’s questions. Thanks for listening. This was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: Please send us more of your questions. We love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice… A: Miracles happen!

Vidas: Hi, guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra V: Let’s start episode 521, of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This questions was sent by Diana. And she writes: When I play an organ I look too much at my hands. So sometimes I lose where I play. And it makes trouble when I need to play in Mass or concert (not only this week). V: Hmm. Interesting question. It’s probably very common among beginners to look at their hands. A: Well, true because if you are beginner, keyboard player as Diana is, then yes, you look at the hands a lot. But then if you are experienced keyboard player but you start to learn to play organ then you look at the pedal a lot. So these two problems are kind of similar. But I guess when she will reach certain level on playing the keyboard she will naturally stop looking at her hands. Because, do you look at your hands a lot while playing keyboards? V: When I improvise, yes. Because where I supposed to look? There is no music. A: Well, yes but we are talking if you have a musical score in front of you. V: Ah. I see. Not so much of course. No. I have to look at the score… A: I know. V: because I don’t know what to play then. A: Sure. V: Do you think she needs some extra attention of looking at the score and not looking down at the fingers or it will just come naturally to her? A: I think is should come naturally. For example, I look at the keyboard early when we are playing duets. And you know why? Because when I’m playing solo I sit in the middle of the keyboard but when we are playing duets, I most often play the upper part but sometimes I play the lower part, and then you sort of have to change your body position and you sit either far right or far left of the keyboard. V: Yes. A: And then the keyboards shifts because of the position of your body and it’s sometimes a little bit hard to coordinate the distances, yes. V: You don’t know which key you will hit. A: Sure. V: Which octave you will hit. A: Yes. Because you are sort of decentralized. So that way, yes, I have sometimes to look at the keyboards because we have such a laughs, that for example, I start to play everything what is written but let’s say a third above or a third below, and it’s so funny, sometimes. V: And we can transpose them. A: Yeah. V: Very nice. I like transposition. A: Yes. So I guess it all comes with experience. Because its often a problem for young organists when they just start playing organ, that they watch at the pedalboard a lot. And then they lose the text. And since Diana is playing violin I guess she is new at the keyboard so that gives her a problem but I think she will overcome it with time. V: Do you think giving herself this idea of really focusing on the score and not on the hands would help her concentrate more and not to look down, like actively looking at the score and not at the hands? A: Yes, I think it would help. V: And remembering not to look down, sort of. A: True. V: Or reminding herself not to look down. A: That’s right. But another problem that some of the new musicians experience; I remember teaching many years back, I had fifteen first graders to teach to play piano. V: Mmm-hmm. Fifteen? A: Yes. Fifteen. V: Oh. A: I had like one lesson with each of them every week. V: How many minutes? A: Maybe two lessons but like a half an hour with each time. V: Wait a second. Half an hour, right? A: Yes. V: Each time. A: Maybe twenty minutes. V: Twenty minutes. A: I’m not so sure right now. I think we had like one academic lesson switched into two hands, divided into two hands. V: Do you miss these days? A: No! No, no, no, no… But that’s a good experience. You have to experience life. And I started to teach them on the First of September, and before Christmas that year, I had to make a contest with them and everybody of them had to perform. V: In front of their parents. A: Yes. So it was really tough. And not only parents but also director of the school. V: You mean principal. A: Principal, yes. V: Mmmmm. A: So, it was really tough. But what I wanted to tell, that some of those kids really didn’t want to read music... V: Mmm-hmm. A: from the score. I was really, probably for half of them the hardest thing to read the score. And what they wanted, these kids, they wanted that I would show on the keyboard how it goes, and they memorize from my hands what is happening. V: They would mimic your hands. A: Yes. Just like apes, you know. V: Monkeys. A: Monkeys, yes. V: Chimps. A: Chimps. V: Ohh. A: And they wouldn’t watch to the score. It would be there for them just to follow their finger… V: Mmm-hmm. A: on the keyboard. And one suddenly realized, ‘it’s just like computer’. V: Mmm-hmm. A: You also have to press a key and then he liked it, actually a lot. V: Because he likes computer. A: Yes. V: Uh-huh. So what was your solution with them? A: Well… V: How did you manage fifteen first graders to play in a Christmas concert in front of their kids, after maybe sixteen, fifteen, weeks of training only? A: Well, we did actually pretty good because what I found out while working with them, that these little kids, they are very observing, observing all the new information and they learn very fast actually. And one of them actually I suggest for his mother to take to a musical school and she did. And he was accepted to study to learn to play cello. And I just recently found out through the social media that he became a professional musician. V: Mmm-hmm. A: And he lives now, I think in Cyprus. V: Really? A: Yes. And he performs sometimes with one colleague from our school, Eugenius. V: Cyprus is an island in the Mediterranean. A: Yes. So I guess my understanding about his talents was real and I’m glad that he chose that way. V: Uh-huh. But you don’t have good memories about your principal, right? A: Well, yeah. V: She. Um… A: Well, she didn’t do anything bad personally to me… V: Yes. A: I think she gave me a job when I really needed and I really appreciated that. V: But? A: But being musician herself and knowing what the horrible station for musicians was in Lithuania at that time, she used us all, I think. V: Mmm-hmm. Employed you without, um… A: Without Social Security? V: Mmm-hmm. A: Yes. So now I don’t have any benefits from those. I was teaching for her for three years. V: Three years? A: Three years, yes. So I guess when I will reach my senior age I will be very sorry that I worked for her for those three years. V: Uh-huh. You could get retirement three years earlier. A: That’s true. But now I will have to work… V: Three more years. A: Yes. V: You see guys, sometimes, musicians, when they become in a position to organize some kind of school and employ other musicians, they abuse those musicians… A: True. V: which are below them. A: Because I remember one teacher that our colleague in Lincoln, back in the USA had. And the sign on that T-shirt said, ‘Unemployed musician. Will work for food’. V: Uh-huh. A: And that’s so true, actually. V: Maybe not necessarily abuse but exploit musicians, exploit her… A: True. V: workers. A: True. V: Right. Wow. So we started talking about Diana’s hands. Nice. Alright, guys, please send us more of your questions. And we will talk about your questions and troubles in our podcast. And maybe we’ll share some of our experiences in a way to create a story out of that. Alright. And remember, when you practice… A: Miracles happen!

Vidas: Hi, guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra V: Let’s start episode 487, of Secrets Of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Andrei. He wrote: I am working on the Sight Reading Master Course and I am struggling with the 32nd notes, how do I count them? V: Very practical question, right, Ausra? A: Yes. V: What do you do with 32nd notes? Do you count them? A: It depends of the piece. If I’m learning a piece by a contemporary composer, then yes, if the smallest note values are 32nd, then yes, I subdivide everything in 32nd—until I learn the text. V: If the music is not familiar and not easily predictable, right? A: Yes. V: Like Messiaen. You count in smallest note values. A: That’s right. There is no other way how to do it. V: But flourishes in the Art of Fugue that my Sight-Reading Master Course is based on, might be well predictable, quite predictable. And I’m thinking whether Andrei has to even count them or not. A: Well, I think that whole thing is to know math a little bit—to know how many notes are in another note value. V: Mmm-hmm. A: For example, you have to realize that in one eighth note, you have two sixteenth notes… V: Mmm-hmm. A: Yes? And in one sixteen note you have two 32nd notes. V: Yeah, it always doubles. A: So you really need to know how much, how many notes is on that certain beat. V: I’m not good at math, but this I understand. A: So, and then you just really need to count. Well, what would you suggest? What would be the best note value to count in this particular example? V: I wrote to Andrei to try counting in eighth notes. A: I think that’s a good advice. V: And if it’s still too many unclear notes, it’s means maybe he’s playing not slow enough. A: Yeah, that could be a problem. V: Right? So in one eighth note you have two sixteenth notes and four 32nd notes. Four 32nd notes total in one eighth note. Is it possible to play four notes without counting? I would think so, yes—in one eighth note. But then you have to really take it really slow—maybe twice as slow as you are playing right now. A: That’s right. I think that wrong tempo might be a problem. Then of course later on when you will master hard parts, you might will play in a faster tempo but not at the beginning. Especially if you are struggling with some rhythmic issues. V: Right. A: And what do you think? Have you encountered that sometimes you tell your students that you need to count and they are telling you ‘oh yes, I’m counting’ but they can still not master it and still play incorrectly rhythmically. V: What I do is I ask them to do aloud, aloud. A: Yes, I think that’s the best… V: With their voice. A: that’s the best way to do it. V: Because if they do this inside of their head, it might seem that they are counting correctly, in a constant tempo, but you never know. A: That’s also what I’m doing with my students when they are writing dictations... V: Mmm-hmm. A: Musical dictations. Especially in one voice, dictations might be quite hard, so if they cannot grasp it and count it, I’m forcing them to count loud. V: So let’s say, in Sight-Reading Master Course, there is a tempo of cut time, alla breve, maybe 2/2 or two half-notes per measure, right? But at the concert tempo you should count in half-notes. But when you practice you could subdivide it in anyway you want. So you could treat it as a 4/4 meter easily. One, two, three, four. But to tell you the truth you could subdivide it in eighth notes—one and two and three and, and count it slowly enough. If that’s too fast, you could count in sixteenth notes also by adding one-e-and-uh, two-e-and-uh, three-e-and-uh, four-e-and-uh. But I don’t think you could even add the additional syllable for the 32nd. That would be like specially composed poem for counting. Maybe we should Google, you know, how to count in 32nd, or even create a special poem. Maybe I could get creative with this and produce something. Do you have an idea? A: Well, I don’t know. I need to think about it. But anyway if you would practice slower and count, I think everything should work out quite well. It all comes with experience. V: Mmm-hmm. One-e-and-uh; it’s like counting in sixteenth notes. So now if you wanted 32nd notes, you should add one additional syllable between each of the sixteen notes; one-e-and-uh, would become, what would be a better syllable to fit here. A: Could you do the same, just in a faster tempo? And it would work for 32nd. V: One-e-and-uh, two-e-and-uh. Yeah, you could. But you could do one-beat-e-beat-and-beat-ah-beat, (laughs) for example. A: I couldn’t do that. It’s too complicated for me. V: Or you could do really creative. Instead of beat you add some organ term with one syllable. What is your favorite one-syllable organ related term? Like flute, for example? One-flute-e-flute-and-flute-ah-flute, for example? A: I don’t think I know many one syllable organ terms. V: You could twist your tongue and go to the doctor afterwards. A: Maybe no. V: Tongue doctor. Is there a doctor like that? A: I don’t think so. I think your tongue is working pretty well so I don’t think you need to worry about it. V: Alright guys. Get creative and if you really want to count in 32nd notes or 64th notes or 128th notes—I don’t know, get wild. Alright. This was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: Please send us more of your questions. We love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice… A: Miracles happen! |

DON'T MISS A THING! FREE UPDATES BY EMAIL.Thank you!You have successfully joined our subscriber list.  Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas

Authors

Drs. Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene Organists of Vilnius University , creators of Secrets of Organ Playing. Our Hauptwerk Setup:

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

This site participates in the Amazon, Thomann and other affiliate programs, the proceeds of which keep it free for anyone to read.

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed