|

I've just returned from my church where I've demonstrated the organ to the group of students from the Art Academy with whom we are collaborating on a project "Living Organ". They are not interesting in a classical organ repertoire. Even improvisations that I do regularly are too traditional for them. What they really want are some experiments with the sound. Let's call them "Soundscapes". Today they wanted me to show if the organ can imitate human voice. Then the sound got out of hand, I used 3 pencils to create some exotic colors - a submarine, a spaceship and of course - a vacuum cleaner. Let me know what you think.

Comments

Vidas: Hi, guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 413 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Eddie. He writes: Hi Vidas and Ausra! I enjoy your ideas on improvisation in the modern style. I am now ready to embark at the fairly late age of 69 today, on the challenging and exciting path of improvisation on the organ. I must confess, however, that I am at this stage a real dummy and raw beginner, but I have a great desire and urge to be able to at least be able to improvise somewhat before I die. I have also embarked on online organ teaching, which is also an exciting endeavor for me. God bless, and keep on with your and your wife’s good work for organists. Regards, Eddie V: What are your thoughts, Ausra, for starters, about Eddie’s improvisation efforts when he is 69 years old? A: I think that it’s amazing that people at various ages pursue their dreams. I think it’s wonderful, because you know that you have dreams, you do something new, you learn something new, it means you will not get old so soon. V: You are so right, Ausra. I just, you know, have this laptop in my lap. And when I open my new window on the browser, by clicking new tab, I get this greeting, “Good morning, Vidas! What is your main focus for today?” The computer talks to me. And there is a sentence for every day, and today, the sentence is, “Anyone who stops learning is old.” (laughs) Henry Ford. A: So it just proves what I am saying, if you are still interested in something and learning new things, it means you are not old. V: Exactly. And the most probably inventive and successful people on earth never stop learning. A: I think it’s very important to stay curious about something all the time. V: That’s right, Ausra. What are you curious today about? A: Well today, I am curious about how I will draw the comic. Because the theme of today is very interesting. It’s Iron Man, and I probably will have to draw Spiky as an Iron Man, and so far I don’t have an idea how to do it. V: Put Spiky in armor. A: That’s right. V: I might have to either develop your idea further, like steal your idea, or do an Iron Man from another character. Maybe our bird, Cornelius. A: That’s true. So now, what do you think about new learning improvisation at the age of 69? Do you think it’s a very hard thing? Or it’s possible? V: No, of course everything is possible. But with age, probably people need more patience. A: Do you think people in general are more patient with age, or not? V: It depends on how you react into, onto the changes and other circumstances around you. I’ve seen people who are patient, and I’ve seen people who are getting very impatient, too. A: So, Vidas, could you tell us what would be your steps if you would be 69 and would want to learn to improvise. What actions would you take? V: I assume Eddie is interested in modern style. I’m interested in modern style as well. So, I’m like the idea of starting small at the beginning. Limiting yourself at the start, and not worrying about too many stylistical ideas or technical details, but choosing just a few notes, maybe 4 notes to improvise on. Like C, D, E, and F. That could be a nice exercise. Start a timer and improvise on those 4 notes without stopping for 2 minutes or 5 minutes or 10 minutes, always trying to do something interesting with those 4 notes. And you can use any octave, any hand, you can play with pedals those pitches, any order you can mix them up. You can have different rhythms, and you can have, of course, different registration, texture. So that would be my first step. And I think it works. A: Yes, I think it would work. V: If 4 notes are too much, you know, some beginners really don’t have a good grasp of 4 fingers at all, so maybe start with one note. Let’s say C. And since you only are worrying about the note C, the pitches are not important. Everything is C. It’s like a percussion instrument, and you are only worrying about rhythms then. And do anything that you want with the pitch C, but try to do interesting rhythms. And after awhile, you can do 2 pitches after a few days, when you get comfortable. C and D. Then you will have more, like what I do with 2 pitches. It’s like, jump from C to D, it’s unbelievable. If you think one note, then suddenly 2 notes. And those 2 notes say a lot, right? I know some people might laugh at the idea, starting with C alone, but it depends on where you are. If you never touched the organ before, or keyboard before, or if you’re so afraid of making mistakes when you improvise, and you will make many mistakes, and that’s okay. Actually, make as many mistakes as you want – the more, the better. That’s my… A: Because it’s improvisation, so there cannot be mistakes. Is that right? V: Yes and no, right? If you say to yourself, “It’s a mistake,” then it’s a mistake, right? If you say “No, it’s not a mistake,” then you can elaborate that so-called mistake into an episode. Sometimes, I improvise and make sound a little bit different than what I intended. But then, I repeat a few times the same idea, and it becomes something that I intentionally did. A: I have noticed that a few times in your improvisation, yes. V: Like I had this very loud episode playing with mixtures and reeds with my hands and feet, like a culmination, and then suddenly I want to play softly, and I gradually, you know, start to reduce the stops on the manuals. Or maybe jump on the second manual and play with strings, and I sometimes forget to reduce the pedals, and this bombarde is, “BUH” like a real trombone, suddenly out of nowhere. A: Like a beast. V: So, what do I do then? I repeat it a few times. A: Repeat it, yes. V: Maybe not right away, but after 10 seconds, I repeat it. Just one note, aha. So then I have 2 trombone notes. And then maybe third time, I repeat the same note again. And maybe listeners will understand, “Oh, that’s intentional, and something, he wants to express some idea with this low bombarde note.” A: So, it’s like cheating your audience, and cheating yourself in a way. V: It’s actually going with the flow. You know, wherever your mind goes, you follow. A: So, if I understand, during improvisation, the most important thing is not to stop. V: Exactly. That is why we recommend timers. Resist the temptation to stop. The first 90 seconds are the most difficult. Actually, the first second is the most difficult. Just to sit down on the bench. A: Very exciting! V: But when you reach, let’s say, 5 minutes, you don’t want to stop. You discover, “oh, that’s interesting,” and you want to elaborate it, and when the timer goes off after maybe 10 minutes, you suddenly think, “Why did it end so quickly?” you know. A: That’s what I also noticed in your improvisations. I think, “this is the culmination, and now the end will come,” but it’s not. There’s another combination and then another one, and how will you finish it up? V: Towards the end of my recital, I have this thought, “How do I finish?” And sometimes, the piece itself, the improvisation itself, suggests the ending, too. Like, if I play some very fast running passages in the hands, maybe I can finish abruptly. We’ve gone downwards or upwards, and stop it like that, like vanishing. Not necessarily five long chords like at the end of a symphony. Sometimes I do that too, of course. A: Very exciting. So I hope Eddie got some ideas from your thoughts. V: And I always say, “Record yourself, and if you are brave, share it online for others to see.” And this feedback will help you grow, will help you sit down on the organ bench again. And participate in our Secrets of Organ Playing Contest. Remember, you don’t have to play repertoire all the time, you can play anything you want. A: Yes, we are looking forward to hear your playing. V: Yes. This was Vidas… A: and Ausra. V: And remember, when you practice… A: Miracles happen! Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start Episode 174 of Ask Vidas and Ausra podcast. This question was sent by Russell. He writes “How to make sense of the chords in the third movement of Messiaen's L’Ascension in order to learn them fairly fast.” Oh, this is a very famous movement, right Ausra? A: Yes, it is. V: And very interesting question. I played this piece a number of years ago and I it’s a fantastic movement. I think I’ve even recorded a video of this performance from St. Paul’s United Methodist Church in Nebraska, Lincoln. On the organ built by Gene Bedient. Remember that recital? A: Yes, I remember it. V: And I think one of comments I received from one of the YouTubers was that I shouldn’t teach people because I play with mistakes. That was really funny. Because, yes, in one of the passages I made a mistake or two in this particular movement. Usually I don't reply to such comments but this time I couldn't resist and asked if he has his own video of this piece from which I could learn. Of course he didn't reply... People who put themselves on the line normally don't criticize others because they know what does it take to be vulnerable. So, then the question is how to make sense of the chords?Obviously, Russell has to be familiar with the modal system that Messiaen is using, right? A: Yes. V: And the best place to get familiar with this is his treatise which is called “The Technique of My Musical Language” which in French is “Technique de mon langage musical.” Forgive my french pronunciation. So, basically in this book Messiaen writes out his influences, rhythmic influences, modal influences, even gregorian chant influences, bird calls influences, hindu rhythms and other things. Right, Ausra? Let’s suppose Russell has read a chapter or two from this book where he would find information about the modes. Right? What else? A: Well that’s the thing. I have you know, read quite a few books actually about Messiaen compositions, about his compositional techniques, which basically consists of you know imitating birds singing, the modes of limited transposition, added note values, and some hindu rhythms, some gregorian chants, you know, influences. But basically, I don’t think it helped me to learn his music faster. Maybe it helped me to understand his music better, but then working on the music itself, on his texts himself, I think I still have to struggle quite a lot. V: Me too. It’s not an easy technique. It’s not an easy writing style. Because he was so original at the time. But what helped me was really to study the modes one by one. And by studying I mean is playing a scale based on this mode from the note C with my right hand only in an octave, a range of one octave, then in two octaves, then in four octaves, then with the left hand up and down, then two hands up and down and treating this mode just like a regular C Major scale and getting familiar myself with it. And then transposing from the note C# and then from D, and then from any other note that it’s possible. Because their modes of limited transposition and you cannot transpose them endlessly. A: Yes, since you reach a certain point you cannot transpose them anymore, that’s why it’s titled modes of limited transposition. V: And then you could play scales of double thirds, or scale of double fourths, or even sixths in each hand just like regular warming up exercise you would find in Hanon or anywhere else. A: But what about particular L’Ascension cycle? What would you do with those chords? V: You take an opening, remember you have big chords at the beginning and then you have to decipher those chords which means you write down on the staff the scale based on those chords and you find out what the mode is. A: But technically would it help you to apply it to the keyboard? V: It would help me. A: And you play it with mistakes, yes? V: Yeah, I’m famous for playing with mistakes. But that doesn’t stop me from playing you see. And the person who makes the most mistakes wins always because they try the most. And Russell can try the most also if he tries to transpose those opening fragments or in the middle whenever he is struggling, wherever he finds difficult spot. A: Wouldn’t it mix him up even more, and would make things even harder? V: Yes and no because Messiaen himself transposes fragments of his modes in the same piece too, in several spots. A: So then why just not you know to exercise more to work on those spots, hard spots more? V: That helps. A: In various tempos, in a slow tempo first and then move tempo ahead a little bit and maybe you know to practice in different rhythmic formulas. V: Dotted rhythms. A: Yes. V: You are right it will help. But you see what you need to do if you are Russell, you need to understand how the fragment is put together, you have to basically deconstruct it. And by creating a mode, right, a string of notes, ascending string of notes based on those chords would help you to understand which mode of limited transposition Messiaen is using at the moment. And then you see “Oh, it’s a second mode”, “Oh, it’s a third mode”, “Oh, maybe it’s a fourth mode.”, you see and maybe even label them on the score with pencil. A: Yes, but it’s very much time consuming don’t you think? V: Oh, what’s the rush Ausra? A: I don’t know. V: We have all the time in the world I think, right? And we are not competing with anybody, right? We are not competing with Messiaen, he’s dead already. May he rest in peace. And we are only competing with ourselves, right? What we achieved yesterday, and today, and tomorrow maybe if we live. Anything else Ausra for parting advice for Russell and others who want to study Messiaen. A: Well be patient. That’s a hard music to learn. V: And if you have never played Messiaen before don’t start with L’Ascension. Right? A: Start with “Le Banquet Celeste.” That’s I think a good piece to start. V: Or maybe “Apparition de l’eglise eternelle” A: You know they both use extremely slow tempo but I think that’s a good way for beginning to learn Messiaen. V: But don’t play “Diptyque”, right? A: Yes, it’s just the second piece that Messiaen composed to the organ but it is very hard. V: Ausra has special memories about this piece. A: Yes, and you know I don’t like those memories. V: It’s more similar to Vierne style than to Messiaen. A: I had to learn it like in a week or two and play it in master class, that’s what’s an awful way to do. V: OK guys, we hope this was useful to you. Please apply our tips in your practice and send us more of your questions. We love helping you grow. This was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: And remember when you practice… A: Miracles happen. Vidas: Let’s start Episode 155 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. This question was sent by Leon, and he writes:

“Thanks for the thought-provoking complex question on how some people hate most modern music. Perhaps it would also help to read some texts on the history of music. Irving Kolodin's "The Continuity of Music" would get him to the 20th century. And then if there is a music school near him, or even now via the internet where he could take a course, even a seminar on 20th century music, that would help. As for myself, it seems to be very random what I have liked and not. For example, I do not like much of Xenakis' music, but his lone organ work, Gmeeoorh, is actually very well structured, and one of my fantasies to be some day to play. After a couple of big Bach works and the Reubke sonata. And a Vierne, etc. Bottom line, sometimes nightmares can become part of the dream, and eventually as you remind us: miracles happen!” Ausra, what Leon is saying probably is that music that we dislike in the beginning sort of grows on you later, especially complex modern music. Do you have this experience in your life? Ausra: Yes, yes, definitely. V: Does your taste change over time, or not? A: Sure, of course. I remember when we first met, I sort of liked early music more. And I was a fan of Buxtehude and Bach; and I still am. And I remember you were a fan of Hindemith and more modern music, yes? So...And actually, you know, during our studies in Lithuania, I would say we had fairly incomplete education in terms of modern music. Because all the focus was based on the common period, and we did not know much about early music and, I mean, about the Middle Ages, and Renaissance music, and early Baroque music. We did not listen much, and we hadn’t studied much of it. And also, of the modern music, because sort of my knowledge before going to the United States was ended up somewhere with the New Vienna School--meaning Schoenberg, Webern, and Berg. I did not know much about later composers of the 20th century; and about the beginning of the 21st century. And then, you know, in the States, during our doctoral studies, we moved to the part of music history first, of the second half of the 20th century; and it really widened up my horizons, because I learned a lot about modern music, and you know, composers like Iannis Xenakis, Luciano Berio and you know, many American composers such as John Adams, and I could name many of them. That’s a new world, you know; but of course, if you study modern music, you have to find out what the composer’s idea was when he wrote a certain composition. Because that’s a very important thing, to find out what is behind it, what the idea is behind it--what composition technique did he use; because, you know, if you don’t know about modern composition techniques, these cannot mean anything to you. Like, for example, I studied Luciano Berio’s Sinfonien. That’s an amazing piece, but you know, you have to know how it’s put together, what’s behind it, the idea of composing a composition. Like, all this musique concrete and using collage technique, and like, you know, tonal serialism, and all that kind of stuff. What about you, Vidas? What’s your experience? V: Well, let me say this for starters: Don’t you think that, let’s say, Bach’s music was quite modern for his day, too? A: Yes, I believe so. V: He was quite groundbreaking in many ways. And remember when he played some fancy stuff after returning from Lubeck, when he was an organist in Arnstadt, his congregation complained that he’s playing too dissonant music, right? Among other things. So, he was well ahead of his time in many ways. And let’s say, composers that we think of as very early music, like Sweelinck--he was probably just as modern as any other contemporary composer back in the day, right? And everybody back in the 18th century, 17th century, played “modern” music, “contemporary” music, “music of living composers.” Either they copied the music by hand, or sometimes they purchased very expensive publications, which were rare in those days. But you could not get away just by playing music from dead composers. Sure, people studied ancient art, and Renaissance traditions, and polyphonic masterpieces, but they did that in order to expand their musical horizons and to further develop their own unique original musical style. Don’t you think, Ausra? A: Yes, that’s right. I couldn’t agree more. V: So today, of course, when humanity’s development is so much more advanced, today we have so many styles to choose from, right? And when I first started playing the organ as you mentioned, I liked early music a lot. And I still do, of course! But I didn’t know much about any other stuff, any other developments; and I didn’t know about ultra-modern music. Then I discovered Paul Hindemith and his creative approach that got me hooked; and I started improvising as I understood Hindemith taught. Of course, that was quite ugly in my case...But that was a natural, probably, development of my personality--my musical taste. And I believe the further you study music, and practice music, you are open with your eyes for influences; and you look for influences everywhere--not only in music, in other forms of art, but also in science, in everyday life; you look for those inspirations, right Ausra? A: Sure, and you know, it’s never easy, probably. Think, for example, about Ligeti’s famous piece “Volumina”, composed for the organ. I think the story behind that piece is that it was banned at the beginning. Remember that story we heard I think in Sweden? But now, it’s one of the most common pieces, and sort of exemplary piece of modern organ music. V: Exactly. I think the best you can do is to stay open to the possibility for chance to fall in love with this music. Not particularly with Volumina, but let’s say music that you don’t understand right now: for example, there was a time that I didn’t particularly like music by Charles Tournemire. His music looked like bizarre melodies and rhythms combined together. He didn’t have well-structured form (or at least I thought it was like that); and for example, contrary to this music, Vierne was very well organized and quite well understood by me. So I thought Vierne was more worthy of respect. And then, of course, music by Jehan Alain--oh, he died young, and his music, many of his pieces are very short, but could be short miniatures; but quite recently I discovered that he was quite a genius, right? And Tournemire also was a genius, I believe, because the more difficult thing for you is to analyze this music. The more original it is, the more unique it is, probably; if it’s on the surface, very clear and well-structured, simple, that doesn’t necessarily mean it is unique or innovative or original. There might be exceptions, like with Mozart for example--brilliant poetic simplicity. But in a lot of cases, people, they create something and they then don’t try to go even further than the extra mile, and think that it’s good enough, and this is an exercise music. (And with Vierne of course, that wasn’t the case; he was a unique inventor, and pushed symphonic French art into the new realms of chromaticism; there is no question about it.) So each of those composers sometimes I don’t appreciate at the beginning, grows on me. Whenever I spend quality time with that composition. So now, I try to be open to new musical compositions and try to sightread every day, some unfamiliar music, some bizarre musical composition that I can get my hands on. Would that work for Leon, do you think? A: Yes, I think so. I think it would work on anybody. Because it’s an important thing, you know, to study, to analyze, to appreciate modern music. V: Because you have to understand, we probably need to express ourselves, express our inner ideas, let them out. We have some songs that we need to sing, of our own--not only songs that Bach wrote, or Scheidemann wrote, or Sweelinck wrote, or Vierne wrote, or Tournemire wrote, or those masters that we adore, right? But sometimes we have to try to create something. And this will be, of course, not perfect, just for starting out; but then, if you understand the need for this, then you obviously start to look for influences and inspirations wherever you can, especially modern music. If you are inclined to create. And I think every human being is sort of inclined to create. Sometimes we’re afraid to create, but nevertheless, it’s good to try. And sometimes, it’s really fun. A: Yes, it is. Even when you study a modern score, it has all that graphic design, sort of unusual for the eye--it’s basically a masterpiece. V: And a lot of people don’t understand that, and say, “Oh, it’s nonsense, it’s rubbish, it’s too dissonant,” right? A: Yes, but I think the more time that we spend with that music, the more familiar you get with it, the more you can appreciate it. I mean, you don’t have to love it and play it every day, but you need to learn to understand it and to appreciate what the composers did. V: Because that music came from the composer’s mind, from the abyss of the human mind, you know? There’s a saying--you remember the name of the professor who told that, “The human mind is an endless abyss.” That was the former director of music department at University of Nebraska in Lincoln. His name was Raymond Haggh. A: Yes. V: And he had this saying, especially after grading freshman papers… A: Students’ papers! V: “The human mind is an endless abyss.” So, try to go further into this abyss. It’s interesting, and you will be surprised what you will find there. A: Yes, and have fun studying modern music. V: And guys, please let us know if you have such experience when the more dissonant music and more advanced music sort of grows on you, and you start to like it later in your life, after spending some quality time with it, right? It would be very interesting to know if we’re not wrong. A: Yes. And remember, when you practice… V: Miracles happen! Vidas: Let’s start Episode 125 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. Listen to the audio version here. And this question was sent by Peter. He writes:

“My challenges are lack of time, and spending/wasting time on other things(!) i.e. lack of willpower. And I think I need to improve my sight-reading if I am going to improve my overall organ-playing. Also, I hate most 'modern' organ-music. On this subject,it might be interesting if you could explain, in one of your blogs, what anybody 'sees' in sour-sounding, discordant 'modern' music. You know the kind I mean - where you are not sure if the player is making lots of wrong notes, or is this what it is supposed to sound like? Many highly competent professionals like this kind of music, but why? One such person said to me, "It's probably more satisfying to play than to listen to." In that case, why play it to an audience? Another said, "Well, I like it, and I'm going to play what I like." (He meant in a recital.) Is it any wonder that the organ is right at the bottom of the pile, in popularity, with the general public? Where I live, if we get an audience of 40 to a recital, that's very good. Usually, it's 20 or under. The idea is dying on its feet and a lot of it has to do with the kind of music people play, as well as the way in which they play it. (There's another topic for discussion - how is it that some people can play all their pieces absolutely accurately, and the performance is dull and boring, and someone else plays with a few mistakes, but it's exciting and attractive? 'Music' certainly is fascinating, as a subject.) I think you may agree with me that, the basic 'purpose' of music - any music - is to create emotion in the mind of the listener. But if that emotion is one of irritation, annoyance and unpleasantness, why would anyone want to repeat the experience? It makes no sense.” It’s a complex question, right Ausra? Ausra: Well, yes; a very broad one. Vidas: In general, I think Peter struggles with modern music comprehension, probably, and discovering the beauty of it. Ausra: Yes. That’s a tricky question to answer, because the term “modern music” is so broad. There are such different types of music in this “modern” organ music. Vidas: There is no longer a mainstream. Ausra: Yes, that’s right, so it’s very hard to describe. But I guess, you know, maybe modern music’s problem is probably too many dissonances. Vidas: Dissonances which people don’t know how to handle in their mind Ausra: Yes. Vidas: They don’t know what they mean; they don’t feel the resolution of the dissonances. Or maybe composers don’t resolve them anymore. Ausra: Yes. And of course, another trouble with modern music is that some of it actually just lost the form of it; and it’s very hard to listen, sometimes, to music which has no shape. Not like sonata form, where you have like 2 main subjects, and then another subject, and then you have all that exposition, and then you have the development of these themes, and then after that recapitulation comes back. Then you have a clear subject, and you can refer to it all the time. Even in a fugue. I don’t think very many listeners appreciate the fugue so much; but still, because you have a subject and it appears over and over again, it makes a fugue bearable to the listener. Vidas: Haha. Good term--“making fugue bearable.” This could be a tagline of some music website or for one of our recitals. Ausra: Well...Okay, and even listening to Bach’s Art of the Fugue, it’s hard work. Of course, you can appreciate such music the better you know it. So if you go to a concert where you know that modern music will be on the program, I suggest you do some research yourself, if you want to really appreciate it. Maybe find a score, or listen to a recording on YouTube, if that’s possible. Or at least maybe you will find a story of how that piece was written. Because sometimes, understanding what the composer felt at that particular moment of this particular composition may light it in another light, and you may understand it better. Vidas: And sometimes it’s a problem of communication, right? Performers don’t make an effort to introduce the music to the audience, either in spoken form or in text, as program notes. So less-experienced concert goers don’t know what to think during such a dissonant performance. Ausra: Yes. And I think another problem is that so much music is written already, that new composers, they try to do something differently. But actually, it’s hard to find something different, and do something differently; because as I said, 700 years of organ music, so...it’s very hard to find something new. So sometimes they want to make it as horrible as possible, to make it sound “new.” Vidas: I think originality is a complex question. Everyone wants to be original, but everything was created before, right? We just repeat history in a new way, perhaps. So the best way to be original, actually, is to combine old things--several things, not one, but several things, in a new and unexpected way; and then you will be original. Ausra: Well, and you know, composers did that time after time, in history, if you look back. It’s sort of, for example, like Romantic composers. They got inspiration not from the Classical music that was just before the Romantic period, but from the Baroque period. And what the Classicals did was, they found inspiration not in Baroque music but in Renaissance music--which was pre-Baroque. So...And they took some things of those old times, and put some new ideas into them. And it worked fairly nicely. Vidas: And I think people like Peter could benefit from sightreading modern music more. Literally taking it apart, and looking at the scores, and seeing how it’s put together helps to appreciate it when you hear it. He wrote that somebody he knows said that it’s probably more pleasant to play it than to listen to it, right? So...which means that he needs to play it more, simply. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: And then he will be able to appreciate modern music more. I’m not saying he should go on a modern music diet… Ausra: Oh, no! Definitely not! Vidas: For the record. But just to include some pieces in your sightreading menu would be helpful. Ausra: Yes. And another thing, I think, is that organists who perform only modern music are making a large mistake. I think they are losing audience, because if you want to play modern music, it’s okay, but you have to keep the right proportion. For example, if you are planning a recital, and it’s an hour long, I would suggest that your modern music wouldn’t take more than 10--well, at the most,15 minutes of your entire recital. Vidas: Mhm. Ausra: And don’t play it at the beginning, because your audience will leave right away! Vidas: You know, it’s another very complex question for people who choose to voluntarily play only modern music in their repertoire. For example, my friends James D. Hicks and Carson Cooman, they are known to perform only pieces that are created recently. James D. Hicks is playing (all over the world!) music from the Nordic countries, and Carson Cooman is a champion for avant garde music and modern music in general. So you could actually build a brand for yourself, of being the one who performs such music. And I don’t think that they worry about losing audience who don’t like such music, right? Because it’s simply not for them. Don’t you think, Ausra? Ausra: Well, yes and no… Vidas: It depends on your goals. If you want to please everyone, then of course, playing only modern music doesn’t help. Ausra: But what about pleasing yourself? For example, I could not just play modern music. Vidas: That’s why you don’t play modern music only. Ausra: I know. Although, I like modern music, and I have played it quite a lot, actually. Vidas: But then, imagine a situation where a person only plays music of dead composers--not only dead composers, but who lived a hundred years ago, two hundred years ago--three or four hundred years ago! If everybody would play this, then the advancement of organ art would be on a minimal scale. Probably creativity would be diminished, in general, in the organ world, because we would be repeating only museum-like performances! Ausra: You know, I don’t think it would be a huge disadvantage for organ music if none of the new pieces would be written, starting from this day on, because there are so many masterpieces already that you wouldn’t be able to play all of them in your entire life, even if you would live for like 200 years. Vidas: This is true. But what about for a composer, who feels the need to create something, to let it out into the world--what about them? Ausra: Well, that’s a tricky question--you got me! Vidas: So, what I meant is, everybody needs to be creative in some way, probably--to spend our days not only in consuming things, but also creating things. Performing music is one of the ways we consume music, and creating music (either in written form or in improvised form) is one of the creative endeavors. So, you could create, actually, stylistically old-fashioned music if you like it, right? It doesn’t diminish your creativity, if you like this particular style. But I think that people who create sooner or later become a little bit dissatisfied with repeating old styles. They want to create something which has never been created before. Ausra: You know, nowadays there are so many composers that I think you will be lucky if after you compose a piece, somebody will actually perform it. You don’t get much chance of that, knowing how competitive this field is. Vidas: Oh, this is another question probably too broad to answer today, but: in this global world, where everybody can create and everybody can share, and many people are doing this, so it’s getting more crowded every day, right--this global world of music? So then, the only way to get noticed, actually, is to stand out--to not follow where everybody else is going, but to lead, to do your own thing, to find your own voice. Ausra: And what I could suggest to Peter is: for example, if he decides to play some modern organ music, choose that modern organ music which was composed by organist composers. Because they actually know how to treat the instrument well. Vidas: Yes. Ausra: Because I have seen many organ compositions that were not composed by organist composers, and they were just disasters, because you can find things that are impossible to play well on the organ, and it sounds bad. But organist composers, that’s another thing. They know how to treat the instrument well. Vidas: What would be one composer you think would sound perhaps satisfactory enough for Peter, for starters? Ausra: Petr Eben maybe? Vidas: His music is not too challenging--not too dissonant? Ausra: Well… Vidas: He is dissonant. Ausra: He is dissonant, but he knows how to treat the organ. Vidas: What about Charles Tournemire? Ausra: Yes, Tournemire also. Vidas: I’m sightreading every day now from his cycle, “L’Orgue Mystique”. And I find that some of his meditations are quite simple in structure and very modal, and therefore sound quite sweet. So, a lot of French composers also do that modal, sweet writing, which you might find helpful, too. Thank you guys, this was very interesting. Please send us more of your questions; we love helping you grow. This was Vidas! Ausra: And Ausra. Vidas: And remember, when you practice… Ausra: Miracles happen. She has received touring artist grants from the Arkansas Arts Council, California Arts Council, the American Embassies in Prague and Vienna, and the Czech Embassy in St. Petersburg. Dr. Scheide regularly performs chamber music with Le Meslange des Plaisirs and Voix seraphique on historic string keyboard instruments; and as Due Solisti (flute/organ) with Czech flutist Zofie Volalkova.

Scheide earned degrees in early music (with honors) and organ performance (organ department prize) at New England Conservatory and the University of Southern California. Her teachers have included John Gibbons and Cherry Rhodes. She teaches harpsichord at Westminster Choir College of Rider University, Princeton, and teaches online and sometimes traditional classes for Rowan College at Burlington. She lives in a 17th-century stone house Wiggan, and plays organ in the 1740 stone barn at Church of the Loving Shepherd, Bournelyf, West Chester. A Founding Member of various early keyboard societies, Dr. Scheide was recently elected to a second term on the Executive Committee of the Philadelphia Philadelphia Chapter., American Guild of Organists. She is also a Past Dean of the San Diego Chapter. Dr. Scheide is also a published composer with a significant discography. Her compositions have been made available through Darcey Press, E.C. Schirmer, Piano Press, Time Warner, Wayne Leupold and World Library. Current commissions include a piece for the 10th Anniversary of the Kimmel Center Organ. Her recordings are available on Dutch HLM, Organ Historical Society, Palatine and Raven labels. In this conversation, Dr. Scheide shares her insights about her fascination with the Nasard stop, Olivier Messiaen's cycle "L'Ascencion", "Labyrinth" by the Czeck composer Petr Eben, and her collaboration initiatives with chamber music. At the end she gives her 3 steps in becoming a better organist so make sure you listen to the very end. Enjoy and share your comments below. And don't forget to help spread the word about the SOP Podcast by sharing it with your organist friends. And if you like it, please head over to iTunes and leave a rating and review. This helps to get this podcast in front of more organists who would find it helpful. Thanks for caring. Listen to the conversation Related Link: http://kathleenscheide.com

Today's question was sent by Paulius. He's is preparing for an organ recital where he will play Praeludium in C, BuxWV 137 by D. Buxtehude, Prelude, Fugue and Variation by C. Franck and my own Op. 39 - Festive Processional. This piece gives him the most trouble and Paulius wants to know how to learn to read complex modern organ music easier.

Listen to our full answer at #AskVidasAndAusra TRANSCRIPT (please tell us if reading the text of these podcasts would be helpful to you): Vidas: Hello guys, this is Vidas. Ausra: And Ausra. Vidas: And we're starting episode 33 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast, and today's question was sent by Paulius, and he asked, "How can I read complex modern music easier?" You see, the situation, Ausra, you remember he is preparing for a recital in Vilnius Cathedral, and he is playing my Opus 39, Festive Processional, and there are a lot of complex notes and rhythms there. He is struggling to read those notes and rhythms correctly. So what would you suggest for him to do first? Ausra: First of all, I think he must analyze how that piece is put together, how it's composed. Because if you will find the key from the composition, how it was set up, I think you will be able to learn it easier. Otherwise if you would just sight-read it, it might not make sense for you. Vidas: Yes, you have to basically deconstruct the piece, right? Ausra: Sure. Vidas: And think about how the piece was put together before in my mind, right? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: So of course, it's not easy because he's not the composer, right? He has to look deep into what's happening, into the music. Do you think that finding out the different modes would help him? Ausra: Sure, I think so, if it's a modal piece, you know. If it's based on a mode, then definitely it would help. Vidas: This music has lots of improvisatory rhythms, because it was improvised first, and then written down, and it's sometimes difficult to play those syncopations, and the complex ties and dotted notes. Ausra: There is only one way to learn it correctly. You must count the smallest rhythmic value and you must count in those values. Vidas: That will help, right? Ausra: Yes that will help. You wouldn't have to do it for the rest of your life, only while you are learning this piece. Vidas: This applies not only for this particular composition but many other modern pieces, right? Ausra: Definitely. Vidas: That people are playing regardless of nationality or style. Ausra: Because, in my opinion, most modern music has very mathematical approach to composing it. If you crack that formula down it will be easy to learn. The hardest thing to find is what formula it is. Vidas: You have to think deep into the chordal structure and keys. Sometimes those difficult looking accidentals and rhythms only mean that there is a hidden key to unlocking this process, right? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: Do you think that doing just once is enough or you have to repeat this process over and over again? Ausra: I think you have to repeat it. Maybe sometimes in order to write in the score in which keys, in which mode in that particular episode. Just like, remember we are learning now. That piece written by you also, which you wrote originally for flute and organ. Now we are playing it with organ duo. Vidas: Again. It seems like music written by me is complicated to play for other people. Ausra: Well it's not that complicated. You just have to know to switch to different key very quickly. Vidas: Yes it's good that sometimes I write the number of accidentals next to the clef for that episode. So you know in that episode how many accidental there are right away. Ausra: Yes, it's very helpful. Vidas: Sometimes I don't write it. Sometimes I write it next to the note. Ausra: If it's easier for you, for example, this episode has three sharps and they are not added to the clef, you can do it yourself. Maybe, on top of that line you just write three sharps or four flats and so on and so forth. Vidas: But you have to do this yourself then. Ausra: The best thing about modern music is, if you will not play it, one hundred percent is written, nobody will notice it. I'm quite sure, so don't panic if you will hit a few wrong notes. Vidas: By the way, what was the last challenging piece for you from the modern period that you cracked down and really learned to play, but it was difficult for you? Ausra: This piece by you, Fantasia on the Themes by M.K. Ciurlionis, Op. 11a, for example, wasn't so easy in the beginning. I had to crack it down. Vidas: And before that? Ausra: Let me think, probably learning Messiaen. Vidas: A lot of people love Messiaen, and it seems like an equal number of people hate Messiaen. Ausra: Well, with Messiaen is a strange thing. I studied his compositional techniques quite a lot and in depth. The better I know his compositions, the less I like them. I don't know why, especially those late ones. Including piano and organ. If I had to choose, I would probably choose his early pieces, like Nativité du Seigneur. Vidas: Do you remember you played Laudes by Petr Eben, Czech composer. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: Was it challenging for you to learn it? Ausra: Well not as much as I expected at first because in the Lithuania we have this big thing him and Laudes. It seems like because professor Digrys started playing this cycle and it seemed like a very big deal. After learning, it myself I didn't find it so hard. It's sort of a mathematical piece too. Of course rhythms give problems. Vidas: You applied your own advice. Ausra: Yes. Petr Eben played organ himself. He knew the instrument very well - it fits into your hands, your feet. It's not like some crazy stuff that you are trying to adapt to your organ. It's actually all very natural. Vidas: It's quite musically easy to guess what's happening once you know the system. Sometimes those polytonal things are difficult to guess but easy to decipher. Ausra: I think the rhythm is probably the most difficult problem in the that organ cycle. Vidas: How about music by Jean Alain. The 2nd Fantasie Was it difficult for you? Ausra: No. Vidas: It's not that easy to play. Ausra: Yes it's not very easy but it's manageable. The most interesting thing I took the 2nd Fantasie after many years of playing it. Now I think the last time I played was way back in the Omaha Cathedral, where I played for the masterclass for Olivier Latry. Now I picked it up and I can almost play it in the right tempo. Vidas: You practiced this piece so many times back then, when myself tried to sight-read this piece a few days ago, it seemed like it was coming back to me too. Ausra: Yes, overall Jean Alain was not my most favorite French composer. I just feel so sorry but his life was so short. Vidas: Right. Second world war. Ausra: It ended so abruptly and so tragically. He would have been such a great composer. Definitely no less famous and good as Messiaen. Vidas: I hope people can apply your tips and really decide for the piece first before practicing any organ piece but specifically challenging complex modern music. Ausra: Sure. Vidas: So guys, please send us more questions. We're really happy help you grow and the best way to do this is through our newsletter. If you subscribe to our blog at www.organduo.lt. You enter your name and e-mail address and you become our subscribers. You can read our blog and you can really communicate with us much easier and send us your questions. We will be happy to discuss them during the show. Also please tell us about the sound quality. We recently purchased a new double lapel microphone and we are sitting in our living right now and chatting. Two lapel microphones are plugged into one smart phone. I hope the sound quality is okay for you. We are testing. Please give us your feedback too. Wonderful. This was Vidas. Ausra: And Ausra. Vidas: Remember when you practice- Ausra: Miracles happen. By Vidas Pinkevicius (get free updates of new posts here) First of all, Merry Christmas to all our readers and students around the world! Ausra and I wish you and your loved ones a blessed time as we gather together to celebrate the most wonderful time of the year! We hope you have someone in your life to share this joy with. If not, let beautiful organ music be your companion too. It works, I'm told. Welcome to Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast #74!

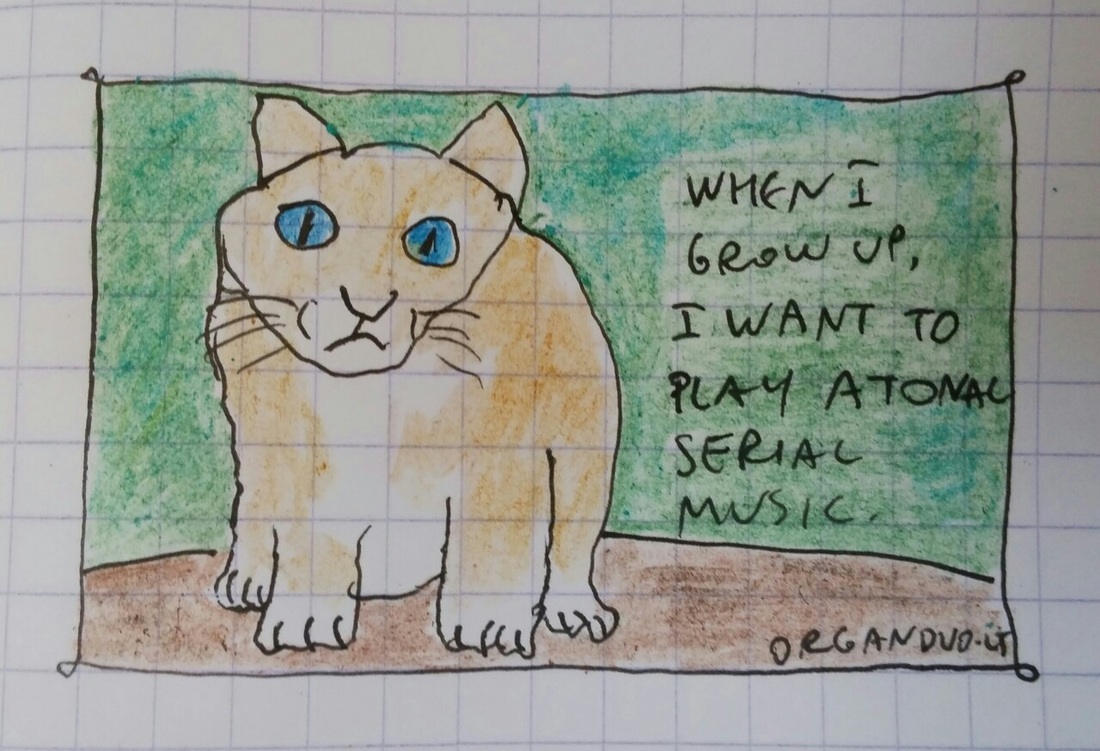

Today's guest is an Italian concert organist Enrico Presti. He has attained diploma in Organ with Prof. Wladimir Matesic in Bologna and degree in Computer Science with mention in the Faculty of Mathematics at the University of Bologna. Enrico attended master classes with Marju Riisikamp, Olivier Latry, Peter Planyavsky and Hans-Ola Ericsson. He performed several concerts in Italy, Luxembourg, Switzerland (Musée Suisse de l’Orgue), Faroese Islands (Summartónar festival, event coordinated by Italian Institute of Culture in Copenhagen), Finland, Baltic States, United Kingdom (Oxford Queen’s College), France, Sweden, Austria, Russia (St. Petersburg), Czech Republic, Romania, Denmark and Germany. From 1996 to 1999 he was managing director of the international concert series Organi Antichi, un patrimonio da ascoltare in Bologna; from 2002 to 2007 he was artistic director of the international concert series Musica Coelestis (Ferrara) and from 2003 to 2005 he was co-artistic director of concert series Al centro la musica (Bologna). Enrico is currently enrolled in the Faculty of Letters and Philosophy at the University of Bologna. In this conversation we talk about avangarde organ music, finding time to practice and the dangers of comparing yourself to others. Enjoy and share your comments below. And don't forget to help spread the word about the SOP Podcast by sharing it with your organist friends. Thanks for caring. Let's go to the conversation By Vidas Pinkevicius There are two basic types of atonal music - serial music and aleatoric music. If you want to write serial music, you want to control as many musical elements as possible. The more, the better. So write a series of notes in which any particular pitch cannot be repeated before an entire series is over. In total serialism you assign each pitch a duration, dynamic level, articulation, and color.

In aleatoric music you leave everything to chance. The pitches are assigned to the specific numbers of the roll of the dice. You roll the dice and write the note that has shown up by accident. Roll some more and write another pitch. Twelve pitches of the chromatic scale - twelve numbers of two dice cubes. That's how it works. There's one thing serial and aleatoric music have in common - they both sound exactly the same. Cats love such music. Every time you see a cat on a keyboard - that's what they're using. "Hey, Tigger, what are you playing?" "I can't decide what I want to play - total serialism or aleatory". "Can't you just compromise? Play serial aleatory or something." One of the factors of organ recital success is familiarity - people love to hear music that they know. Does this mean there is no place for modern music in people hearts? Watch this video with insights from me and Ausra. Do you play new organ music in public? How do people react? Share your thoughts in the comments.

|

DON'T MISS A THING! FREE UPDATES BY EMAIL.Thank you!You have successfully joined our subscriber list.  Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas

Authors

Drs. Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene Organists of Vilnius University , creators of Secrets of Organ Playing. Our Hauptwerk Setup:

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

This site participates in the Amazon, Thomann and other affiliate programs, the proceeds of which keep it free for anyone to read.

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed