AVA169: Is There Anybody In The World That Can Properly Play Baroque Pieces With Toes Only?3/3/2018 Vidas: Let’s start Episode 169 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. Today’s question was sent by Mike. He writes,

Hello Vidas. Are there any YouTube examples of Bach's main fugues, toes only? Is there anybody in the world that can (properly) play the great 'g minor fugue' toes only? Can you? If not, i 'rest my case' - knowing 'pigs can't fly'. If there are - i will ask the pope for forgiveness. Best, Mike Do you know, Ausra, what he’s talking about? It’s an excerpt of our correspondence via email. I decided to answer his question here publicly, too, because he thinks that Bach’s fugues cannot be really played with toes only, virtuosically enough. A: On the pedal? In the pedal part? V: Yeah. For example, the famous Gigue Fugue, BWV 577--especially in the upper register, where you have the theme in the tenor octave. So, he thinks that you need heel for that, not only toes; and I wrote to him that of course it can be done, but it doesn’t have to be played very fast, of course. A lot of people play it very fast. But when people observe, let’s say, Cameron Carpenter, right--and he plays virtuosically with heels also--then it really is difficult to prove the historical way of playing pedals, right? A: Well, some people are just stubborn, I guess! V: Or, you know...Cameron Carpenter in their mind is a demigod, right? Because he can do anything, right, and therefore what they see on YouTube is probably more convincing than what we tell them. Right? I don’t feel that we need to convince anybody here. A: Me too. Whatever. Whatever he chooses--whatever suits him. V: Mhm. We just share our experiences, how we do things, right? A: Yes, yes, yes. V: Would you play BWV 577 fugue extremely fast? A: No. V: Even if it’s a gigue, right? A: Yes. It shows just poor taste, in my opinion. V: Is it a dance, or a race? A: Well, it’s a dance! V: Exactly. For people who are probably wondering about the tempos in dance-like fugues, they need to get familiar with the dance tempos, too... A: Sure. V: And dance steps, and dance figures--how they are taught to dance, historically. Right? So we were, in those seminars, remember? A: Yes. I think the most important thing for any musician is to learn to hear what you are playing, actually--to really listen to what you are playing. And if you would pick an extremely fast tempo, I don’t think you will be able to hear what you are playing. V: Mhm. A: And then, in my opinion, music loses its sense...its main purpose. V: You said Mike is stubborn. But we are stubborn, too. A: I didn’t say that Mike is stubborn! I think, you know, well...If somebody already knows our opinion about playing Bach with toes only, and still sends these questions, it means...you know… V: They don’t believe us. A: Yes. So, you know, I am not in a position to try to convince him to accept our opinion. It doesn’t matter what anybody will tell me, I will just stick to my opinion. V: Mhm. We are also stubborn, right? A: Yes. Yes, I’m stubborn. And I have tried enough historical instruments that were built during Bach’s lifetime, that I would know that it’s impossible on those instruments to use the heel. So...why do I have to play it with the heel, if I can play it perfectly with only my toes? V: Exactly. And we were not always that way, right, Ausra? We were taught to play historical music with heels as well, in the beginning. A: Yes, we had to relearn it. V: Mhm. It wasn’t easy. A: Yes, it was hard. V: Who first introduced you to historical techniques? A: Pamela Ruiter-Feenstra. V: Right. And in Lithuania nobody really told you about that, or…? A: No. Nobody. Nobody. Nobody! Absolutely nobody! V: I see. A: Because everybody at the Academy of Music in those days taught to play Bach combined--combining, you know, toes and heels. V: You know, I feel that our former professors in Lithuania had their own version of historical techniques, right? Their own understanding, and how they applied it in their own playing, and it’s not necessarily historically accurate. A: But let’s be, you know… V: Honest? A: Honest, yes. That’s the word I was looking for. That nobody in Lithuania taught us historical fingering; nobody taught us historical pedaling. That’s it. They had, sort of, their own mixed version of what is historical and what is not. And I remember right now, when playing pieces, for example, by Buxtehude or Bach, and if there would be a suspension on the strong beat, I would be told sometimes, even, just… V: Make a rest? A: Make a rest. Instead of that suspension. Which is, I think, highly inappropriate. V: To lean on dissonances. A: Yes, you have to lean on dissonances. You have to even prolong them. And not make rests instead of them. V: Mhm, mhm. Why? A: Well...I think it’s because of the historical tunings, probably. One of the reasons. And another thing: I think dissonances are more important in music than consonances. V: Obviously, because dissonances give music color. A: Sure. V: Spice. A: Yes. V: Like your breakfast for today--it had some spices, right? It wasn’t a very boring breakfast--you put some...What did you put, by the way? What spice? A: Crest salad. V: Crest salad, right. Do you like to water it in the morning? A: Yes. V: Do you like to talk to it in the morning? A: Yes. V: What did you say to that Crest salad this morning? A: “Good morning!” V: “Good morning?” A: “Grow up faster, and we will eat you!” V: Hahaha! A: Soon. V: Was it happy? A: Yes. V: That’s what they do, right? A: Yes. V: They serve us. And actually, we have to be grateful that these little plants give their lives for us. Right? A: They give us vitamins that we need, so… V: Exactly. And we try to give our best experience to you guys. And we hope that it’s helpful to you. And even if it’s not, it’s okay, right? We don’t try to convince you to follow a historical way of playing. I think our understanding of the historical way of playing stems from our knowledge of historical instruments, right Ausra? A: Sure. V: And what it means is that you guys probably need to try out as many historically built instruments--either real historical organs, or replicas built in modern times, right? So THEN you will have an informed opinion on what is possible or not. A: That’s true. V: Right? Right now, probably your opinion is limited to your current understanding of what you see on YouTube. But YouTube is not everything. A: Hahaha! Yes. V: So, any closing ideas, Ausra, for them? For our listeners? A: Well, just try to expand your horizons. V: And talk to your Crest salad. It’s good for plants. Thanks, guys, this was Vidas! A: And Ausra. V: And remember, when you practice… A: Miracles happen.

Comments

I always hear people saying, "you should play Bach with toes only. Avoid using heels. Heels are bad." But why? Why can't we play with heels? In fact, why can't we use heels-only technique? It's all about articulation, isn't it? Avoid legato touch in Bach. Have you tried to play legato with heels only? It's a nightmare. And the toes! The toes can be used for a lot of other things. Instead of thumbing-down, we could have toes-up technique. Sure, you have to develop some flexibility to reach those manuals with your toes, but maybe they could build a second pedalboard? I've heard they had something like that in Germany more than 100 years ago. "Aristide, perhaps you should consider building a few of the stops down there that we could operate with toes." "No, I don't need a page turner anymore, I have my toes for that!" Why is pedal playing of northern and southern European traditions so different? In North Germany, they could play extended pedal passages spanning entire pedal board. In Italy, the most they could muster were a few sustained pedal notes. Does that seem fair? You know what I think? I think all of this has to do with the way Catholics and Lutherans approached organ music. For Lutherans in Germany, organ music was embraced in it's highest forms, advanced pedal playing being one of them. "Dieterich, show us what your third hand can do. Actually you have 4 hands now so play double pedals." For Catholics, organ music was tolerated as long as it didn't draw too much attention to itself. "Girolamo, stop making all that noise with your feet. We're trying to pray here." Karl asks why we can see some videos online where even master organists use heels when they play music written up until 1800s.

Heel playing was not comfortable on early organs because of the construction of the pedalboard - it was flat, sometimes the pedals were short, sometimes the range was very wide. Besides, in those days, the main practice instrument for organists was pedal clavichord which also can't really be played using heels. That's why there is a tradition not to use heels in music composed until approximately 19th century (there was certainly some evidence for heel playing in early times as well - perhaps maybe as an exclusion to this tradition). However, not every organist abides by this rule. Not even every master organist is so strict. That's probably because early performance practice technique were re-discovered in the 1970s together with the first wave of historically inspired organ building. Some master organists decided to re-learn playing techniques (manual as well as pedal) and some not. Some were mature organists already when this was starting to happen and they learned to use heels and play legato early in their career. To erase all this and start learning from scratch - not everyone is so brave (I was lucky to have studied with two of them - Quentin Faulkner and George Ritchie). There are organists who advocate for early techniques to be used only on early instruments. They say that wider keys and radiated pedalboards make it impractical to avoid finger and pedal glissandos and substitutions, make it impractical to play with toes only the music of Bach, for example. Others argue that it would be counterproductive and illogical to learn the same piece in two ways - one to be played on early instruments and one on modern and so they choose early technique on both types. What do you think? A couple of weeks ago when I asked my readers what it is they struggle the most in achieving their goals in organ playing, I was surprised how many of them answered "Organ Technique".

I wasn't expecting this answer to show up so frequently in their emails because I constantly write about these technical issues of organ playing, among other things. When I think about it now, of course it makes sense - lots of people find their left hand technique too weak in comparison with the right hand. Techniques like pedal preparation are so powerful in making ones pedal playing automatic, yet so few people really take advantage of it in their daily practice. In particular, I found that left hand and pedal coordination is a real pain for the majority of organists. This is so true because when people come to the organ after having studied piano for some time, one of the first things they need to overcome is this notion of reading music from 3 staves (and the bottom stave is not suited for the left hand part, as in the piano, but for the pedals). So in order to help overcome the struggles many people are having with their technique, today I have finally completed my new audio Organ Technique Training. If technical aspects of organ playing are holding you back from achieving your dreams, I suggest you check it out. Sometimes I get asked why is it so that not every person who is aware about early pedal technique uses it? In other words, why some people still play early pieces using heels although they know that the original way was to play with toes only?

Or why many people still use finger substitution for Baroque music when they are aware that it came into fashion only in the Romantic period when there was a need to play with perfect legato? I think it all depends on the person. It might well be that such an organist was taught toes only technique for the early music but as it often happens, some people get distracted and don't apply in practice the techniques they learned some time ago. That applies to some of my colleagues, too. They might know about this but still use toe heel technique and finger substitutions for this kind of music. It really feels awkward the first time you do it the right way. You have to get used to that. But the right kind of instrument also helps you to feel the correct touch and technique. So if it was a modern instrument with standard keys and AGO radiated pedalboard, then not too many people feel they need an "early" technique for such instruments. To me, it would be counter-productive to practice "the modern way" and the "early" way. But that's me. Other people feel different about it. In fact, I was talking about this point with one of my colleagues a few months ago here in Lithuania, and he said the following: "when I will go to play the Silbermann organ in Saxony, then I'll re-learn the piece." He was playing computer organ at the time. What a waist of time and energy - isn't it better to learn a new piece the right way during that time? By the way, do you want to learn my special powerful techniques which help me to master any piece of organ music up to 10 times faster? If so, download my video Organ Practice Guide. Although alternate toes technique was the most popular type of pedaling used in Renaissance and Baroque organ music, quite often we have to use the same foot technique as well. It is important for an organist to recognize the differences of alternate toes and same foot technique because it affects our pedaling choices. If you know in which type of passages playing with the same foot is the best choice, you will quickly learn to see the familiar patterns in your pedal lines. In this article, I will give you the most important instances of using the same foot technique in early organ music.

Same Foot before Changing Direction On passages in quarter, eighth, and sixteenth notes sometimes we use same foot instead of alternate toes technique. Here applies the general rule: use same foot before changing direction. This means that in a passage like C D E D we play with the same foot notes D and E because after ascending notes D and E the melody changes direction downwards. So the entire passage, such as C D E D E F G F G A B G would be played left, right, right, left, left, right, right, left, left, right, right, left, and left. Same Foot on Long Note Values in Extreme Edges of the Pedal Board In Baroque and Renaissance organ music, chorale-based compositions often employ cantus firmus technique – placement of the chorale melody in long note values (half and whole notes). Cantus firmus method can be used in any voice. Instances of cantus firmus in the bass were especially common because they could be played on a separate pedal division with a different sound color. Moreover, if cantus firmus was used in any other voice, it could still often be played with the pedals. The normal way of pedaling such melodies was alternate toes technique. However, in extreme edges of the pedal board one could play long notes with one foot because the traditional alternate toes technique is uncomfortable. I recommend that you write in pedaling in every piece you play on the organ, at least in the beginning. This will prevent you from making accidental pedaling choices which will not necessarily be correct and efficient. With experience, however, you will start to notice familiar patterns in pedal lines of your organ music and gradually your pedaling choices will become automatic and natural. In other words, if you practice writing in the correct pedaling regularly, with time your pedaling will become instinctive and you will not need to write in any of it. By the way, do you want to learn to play the King of Instruments - the pipe organ? If so, download my FREE video guide: "How to Master Any Organ Composition" in which I will show you my EXACT steps, techniques, and methods that I use to practice, learn and master any piece of organ music. Early organ music requires different kind of pedaling than Romantic and modern compositions. Like fingering, pedaling techniques used in the Renaissance and Baroque music depends not only on different stylistic trends and compositional style but also on major differences in organ building and construction. Just like fingering, choosing correct pedaling allows good articulation, phrasing, and touch, among other things. In other words, if you know the general ideas and concepts of the pedaling used in early organ music, pedaling itself will help you play the music in style and you will achieve the correct articulation naturally. Whether you play music of Schlick, Buxtehude, Sweelinck, Bach, or any other Renaissance or Baroque composer, you will benefit from the correct pedaling methods. Today I would like to reveal the most commonly used pedaling technique for 16th, 17th, and 18th century organ music.

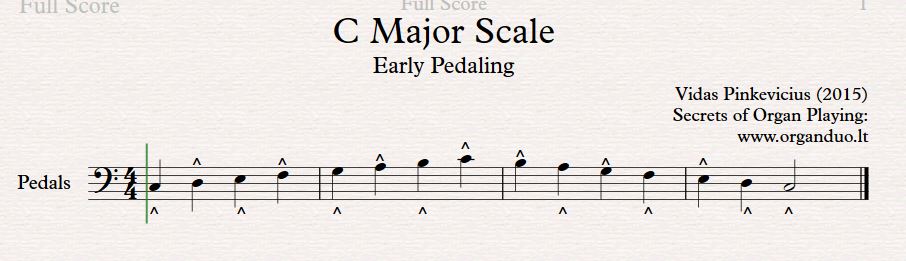

Do Not Use Heels The rule in pedaling early organ music is to avoid using heels. In countries, like France, pedal keys were very narrow and it could be played using toes only. Moreover, very often organ bench on historical organs was in a position were playing with heels was simply impossible. In other words, the full foot of an organist could not fit between the organ bench and the sharp keys. Although in Italy pedal keys were not as narrow, they were quite short. So the only option on many organs was to play with toes. In addition, on the clavichord sound made by the heel would produce a squeaking effect. Since clavichord technique was the basis of organist technique as well, all toes pedaling is the best choice in early organ music. Alternate Toes Perhaps the most popular pedaling technique in early organ music is alternate toes. It basically means that some passages of pedal lines should be played using toes of left and right foot in alternation. For example, try to play the ascending C major scale in this way: left-right-left-right-left and so on. Start the descending scale with the right foot. Make sure that the notes would not be played legato. In other words, you should try to achieve small articulation between notes. Shorten every other note a little so that you will make small accents on strong beats. Note that you should not use feet crossing with this technique. In other words, do not put you foot behind or in front of the other. Instead, move both your feet together as a unit. If you perform the C major scale in this way, it will be easy to feel the pulse and alternation of strong and week beats. The typical use of alternate toes technique also is in the descending pairs of sixteenth notes, such CD BC AB GA FG EF DE etc. I recommend regular practice of major and minor scales in most common keys using alternate toes technique. In other words, play scales with up to two accidentals which were the most often used in the Renessaince and Baroque music. This practice will help you to master not only this technique but also the natural articulation. By the way, do you want to learn to play the King of Instruments - the pipe organ? If so, download my FREE video guide: "How to Master Any Organ Composition" in which I will show you my EXACT steps, techniques, and methods that I use to practice, learn and master any piece of organ music. |

DON'T MISS A THING! FREE UPDATES BY EMAIL.Thank you!You have successfully joined our subscriber list.  Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas

Authors

Drs. Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene Organists of Vilnius University , creators of Secrets of Organ Playing. Our Hauptwerk Setup:

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

This site participates in the Amazon, Thomann and other affiliate programs, the proceeds of which keep it free for anyone to read.

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed