|

Vidas: Hi guys! This is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 441 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Dan, And he writes: Hi Vidas, I noticed that you’d uploaded to YouTube, a version of Carillon of Westminster by Louis Vierne, where you’re playing it slowly. I know you normally do this, so people can transcribe what you’re doing, and eventually produce a print score with fingering and pedaling. This as well, may help me, as I learn things by ear here, due to being totally blind, and finding Braille music to be tedious, and slow. So along with helping people to transcribe stuff, I’d say what you’re doing with that, is also helpful to me too. Take care. And then I asked Dan this question: What is the easiest way for you to learn music by ear? When you hear entire texture or separate hands and feet? Or even separate voices? And Dan replied, What I usually like is to have separate hands and feet, and then entire texture to work with. That has worked well over the years for me. I’ll then take that and work on its parts separately to start out, then manuals only, then right hand and pedal, left hand and pedal, and then put things together. What do you think, Ausra? First of all, could our videos be helpful to people who cannot see? A: I guess, yes, when you record the music really slowly. I guess this might help. V: And even if it’s faster music, it’s possible to slow down twice, by reducing the speed on YouTube. A: Well yes, but then the key will change. V: By an octave, exactly. Lower an octave. But some players, obviously not on YouTube, but some audio players have the possibility to reduce the speed, but to keep the pitch constant. Like VLS player, I guess, can do that. A: Excellent. I didn’t know about it. V: So what people can do is just download the mp3 file from any of our video, and then play it on the VLC player on their computer, and reduce the speed by keeping the pitch constant, and that way will be possible. I remember playing in one international organ festival in our Curonian peninsula on the Baltic Sea, and this is a resort spot, very wonderful place to visit in the summer especially. And I once played there continuo part on the small chest organ, continuo part from Bach’s cantatas, two cantatas, I think. And I was using original notation for continuo, without any chords spelled out, just numbers above the bass. And I supplied the chords by myself, like improvisation. And it wasn’t easy, so I got this YouTube recording of Bach cantata, and played it through VLC media player, by reducing the speed by half, but the pitch was constant. And it worked for me, you know, to master my chords playing and continuo playing together with orchestra this way at home. A: Excellent. V: For awhile, I didn’t do this all the time. Just maybe a few days. So, technology can be helpful today, even for these sorts of things. And then, you know, Dan says he like to have both, entire texture and separate texture for hands and feet. It’s very natural, I think, it’s like a normal practice procedure for everybody. Right, Ausra? A: True. At least it should be. V: Mm hm. When the piece is difficult, we subdivide the texture into separate voices and play them separately, and then combinations of parts. And that’s what Dan needs, and people who probably cannot see also appreciate as well. And then, of course, when they know the texture well, they are ready to play four part texture, or entire texture, and then in a slow tempo, obviously, at first, but videos can be helpful as well. Because, you see, Braille music is slow and tedious for him. I always thought that, you know, it’s a special system to be used for blind people, but today probably, there are more options and people can choose, and it’s not the fastest way. A: Well, you know, I’m not blind, you know, obviously, but I can understand Dan, why it’s easier for him to listen and then to reproduce, you know, music, than comparing to Braille. Because you know, in Braille, you have to touch things to know what is written. V: Exactly. And you have to have a special printer for that. A: Well, yes, but that’s all the technicalities. But since Dan is a musician, it means you know, he has good pitch. Well-developed pitch. And I think it’s easier for musicians, you know, to learn by ear than by touching things. V: Helmut Walcha, remember Walcha? A: Walcha, the blind German organist and composer, yes. I don’t remember him, but I remember our professor, George Ritchie, talking about him, because he was his teacher. V: In Germany. A: Yes. V: And what did he do? A: Well, he would ask his students to play, you know, one voice of the piece really slowly, and then he would memorize it, and then another voice. And in such a manner, he would learn the entire piece. V: It was before the time of videos, and recordings, probably. Recordings were possible, but not maybe cassette recordings, maybe LP recordings, and that was impossible to record at home by your own equipment, you had to have industrial equipment for that. Or, the help of other people, who would play back a melody to you. Mm hm. Excellent. I wish the technology would be advanced enough that they could grab an audio file and then take it apart into separate tracks or voices. And they could do this with MIDI files. And MIDI file can be created by playing it on the synthesizer connected with your computer. And then you could have entire score, entire texture, and then separate parts, or any combination of parts if you want. A: I guess, you know, since every human being, you know, has a different understanding of the world, because some of us are very visual. Some of us, you know, understand words with our ears. And some understand words with entire body. So I guess, you know, everybody has to choose what is the easier way for them to comprehend, to learn music. V: It would be a good business model for organists who would like to focus and specialize for blind people, blind organists, for resources like that. Who would produce audio files – you don’t need videos for that, just audio – for separate voices, combinations of voices, and entire texture. And there are quite a few blind organists in the world, so that could be a niche and very helpful for people. A: Maybe French are doing that, since we have such a long-lasting tradition of, you know, blind organists. V: If they’re doing some, maybe, they are not doing this on the internet. I haven’t seen this yet. A: Could be. V: Yes. But even if Dan or people who could not see, would just take this audio file or video, and play back in a slow tempo, the entire texture, it’s possible to pick up separate voices, right, and develop your own musicality this way much better. You know, you’re like your own teacher this way. It’s not easy at first, because you have to hear inner voices. But with practice, probably people can develop this. At least, Dan is suggesting, between the lines, that it’s helpful. Right? A: True. V: Okay guys, lots to think about. Please keep sending us your wonderful questions. We love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice, A: Miracles happen.

Comments

By Vidas Pinkevicius (get free updates of new posts here)

One of our subscribers was wondering whether or not my Melodic Dictation Master Course Level 1 is a good fit for her. These types of dictations are being taught at National Ciurlionis School of Arts in Vilnius, Lithuania where I teach. Right from the start, from Grade 1 students start writing short 2 or 4 measure phrases. The teacher would play the melody several times quite slowly and the student would write it down without looking at the keyboard. The treble A is given with the tonic chord of it's key. If you know the circle of fifths, you can discover how many accidentals does this major or minor key have. So basically is a process of notating on paper what you hear. Later we make the melodies longer - 8 measures. Different keys, different meter signatures. In Grade 6 we add a a second voice. In Grade 7 we add simple chromaticisms. In Grade 8 the second voice moves to the bass clef. In Grade 9 we have modulations and temporary tonicisations during the dictation. In Grade 10 we start 3 part dictation. In Grade 11 the dictation further complicates and in Grade 12 it's like a small polyphonic composition in 3 parts, maybe like an exposition of the fugue. Usually the dictation is played as many times as there are measures plus a couple more times to edit it. I have to point out that dictation is only 1/5 of the activities our school does in ear training. The other 4 are: 1. Singing 1 part or Two part or Three-part melodies (one voice is sung and the rest are played. 2. Sight-reading one one-part melody. 3. Singing elements of musical language: tetrachords, scales, modes, intervals, chords, and chord progressions. 4. Listening and writing down the above elements of musical language. In the 9th grade we start music theory and in Grade 10 - Harmony. In the end the student becomes a complete musician because they can understand music that they see, hear and play on a deep level. Some of them go on to create and improvise music of their own instead of just performing what others have written. Hope this helps to decide if this course would work for you. [Thanks to Dolly] Some people can't practice organ at home - they have to go to church to access the instrument. And that's not always as convenient as it might seem because you have to be in nobody's way. Here's what David writes: "Thank you for your excellent videos and emails - they have really helped me improve my playing and given me more confidence. If you are in a situation like David, you can also try playing the organ without the stops on - silently - hearing the music in your head. This way you can save much time and use it when YOU want, not only when the church is empty. I do it all the time at St. John's because there are always throngs of local and international tourists visiting the city, Vilnius University, and this church. Sometimes people connected with the University are laid out in the chapel which makes loud playing also impossible. I can't say that it's a worse practice without the sound. No, simply you have to get used to listen with your mind. That's why ear training comes in handy too for organists. Ausra's Harmony Exercise: About 6 weeks ago I played a recital in my church of organ improvisations with multimedia slides based on selected paintings of my father which coincided with the exhibition "Life - Painting" we put together in the City Hall of Vilnius.

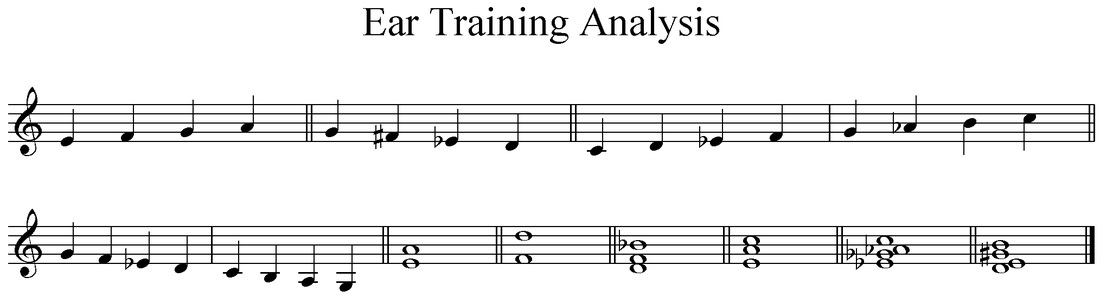

Today I would like to share with you an excerpt of the improvisation on the painting "Saint Michael the Archangel" which was played that evening. I want you to watch this short video with very special intent. As you listen, take a sheet of paper and try to recognize and write down the names of 25 major chords that I'm playing in this video (the opening chord is E major and the video ends with G major chord). After you have completed this exercise, here is another video with correct answers provided on the screen, if you want to check your results. This will be an excellent exercise in ear training. Listen to this file once and write with pencil the names of the elements of music that you heard in this exercise. There are 2 tetrachords, 2 scales, 2 intervals and 2 chords (10 total) and each of them are played twice.

Here is the answer key. After you are done, post the number of your correct items in the comments. Ear Training for Organists: Overcoming Difficulties When Recognizing Scales, Intervals, and Chords4/18/2013 In this article, I will share with you some of the most efficient ways you can teach yourself to recognize various elements of musical language, namely modes or scales, intervals, and chords which are all part of ear training.

The reason you should take aside some time regularly for ear training is not only because then you will develop perfect pitch but also become a more complete musician. Then you will be able not only to perform your organ music but also understand how the piece is put together which will enhance greatly your and your listener's appreciation of the pieces your play. However, it is not easy to recognize intervals, modes, or chords, if you are not following step-by-step systematic approach. Many people simply get overwhelmed, frustrated, and quit their ear training because of that and even start to question whether or not this skill is practical and useful. So it is even more important to overcome these obstacles and here is how to do it in 4 simple steps. 1) Play. The first step to take is to play these musical elements on the keyboard. Simply choose a scale, an interval, or a chord and play it from any of the 7 diatonic notes and later from the 5 chromatic notes. 2) Listen. After playing becomes easy, ask somebody to play the elements for you and try to recognize them. In order to make this step easier you could also record yourself playing scales, intervals, and chords from Step 1 and play them back using any device you have at hand. 3) Write. If you feel that you can recognize these elements most of the time correctly, try to write them yourself on a stave with pencil. Again, follow the order from Step 1 - first write from diatonic notes and later from chromatic notes. 4) Sing. The last step in mastering scales, intervals, and chords is to simply sing them. Now that you have done the previous 3 steps, singing should be just a little more difficult. Be very systematic about it and don't stop the exercise until you can do it at least 3 times in a row correctly and in tune. By the way, do you want to learn my special powerful techniques which help me to master any piece of organ music up to 10 times faster? If so, download my Organ Practice Guide. Did you know that you can turn your organ pieces into powerful ear training exercises? This trick is amazingly simple to use yet very few people take advantage of it. Here it is:

Open a polyphonic organ composition that you are working on right now (it could be any chorale prelude, fugue, ricercar, chorale fantasia etc.). Remember, one of the first steps to take, if you want to master this piece is to practice in separate voices (soprano, alto, tenor, or bass). But instead of playing them on the organ, try to sing them. You can use solfege syllables but if you are not comfortable using do, re, mi and so on, you can sing using neutral syllables, such as la, la, la. Through this method of practice you are not only getting to know each line on a deeper level but you are also training your ear. It is best if you don’t play the line which you are supposed to sing at the same time. To make singing without an instrument easier, you can imagine the scale degrees of the particular key you are currently in. You can even write them with pencil on the score. To take this practice one step further, you can sing one voice, but play another and vice versa. Later on add another voice until you can play three voices and sing any fourth one in a four-part piece. Start applying these tips in your organ practice today. In just two weeks, you will begin to discover some tremendous changes in your ear training skills and analytical abilities which will help you advance as an organist to the next level. By the way, do you want to learn my special powerful techniques which help me to master any piece of organ music up to 10 times faster? If so, download my video Organ Practice Guide. This is my systematic 9 step approach in writing a melodic dictation. Each step is described in a separate video: STEP: 1 Tonality STEP: 2 Key Signatures STEP: 3 Starting and Ending Notes STEP: 4 Range STEP: 5 Mode STEP: 6 Meter STEP: 7 Downbeat and Upbeat STEP: 8 Rhythm STEP: 9 Melody If you are really serious about developing perfect pitch and advancing in ear training while practicing only 15 minutes a day, check out my Melodic Dictation Master Course.

Organists who have some experience in ear training are at the advantage than those who don't. People with perfect pitch and advanced skill at analyzing musical scores can appreciate the compositions at a much deeper level. If you have never had a formal musical education or your education happened a long time ago, you can start improving your musicality and ear training today. In fact, it is possible to combine both ear training and organ practice. In this article, I will give you tips on how to achieve this.

One of the best ways for organists to integrate ear training exercises into their organ practice is to try to play polyphonic music, such as chorale preludes while singing one part and playing the others. For best results, do not double the voice that you are singing on the instrument. If you are new to such practice, take a really slow tempo at first. Aim for at least 3 correct repetitions of each version. If you make a mistake, stop and go back a few measures, and correct them 3 times in a row. Remember that you don't have to play and sing all parts together right away. To make this practice fun and easy, you can first sing each line of the piece without the help of an organ. Then practice 2 voices (one singing and the other playing). Later proceed to 3 parts and finally, learn all 4 parts (singing each line and playing 3 others). Singing separate parts while playing is a strenuous exercise but quite indispensable for a real education of musician. In fact, students sing this way in ear training classes. Of course, at the beginning they only sing one voice but from about 3rd year they start to practice exercises in two voices which are notated on one staff. They sing one voice and play the other and vice versa. With time the exercises get more advanced, melodies are notated in two staves, and the bass clef is introduced. The musical language gets more chromatic, with tonicizations, modulations, complex rhythms and time signatures. From about 9th year into ear training students start to sing in various C clefs. From the 10th year 3-part and 4-part writing is introduced. At the end of air training course, people start to sing polyphonic 3-part and 4-part compositions, which are basically excerpts from fugues. It probably seems like a huge amount of exercise material and it really is. The best way not to get overwhelmed by the complexity of music education is to aim low and set manageable goals. Focus on small achievements but practice regularly. And remember that with each step you master you move closer to your goal one step at a time. By the way, do you want to learn to play the King of Instruments - the pipe organ? If so, download my FREE video guide: "How to Master Any Organ Composition" in which I will show you my EXACT steps, techniques, and methods that I use to practice, learn and master any piece of organ music. |

DON'T MISS A THING! FREE UPDATES BY EMAIL.Thank you!You have successfully joined our subscriber list.  Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas

Authors

Drs. Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene Organists of Vilnius University , creators of Secrets of Organ Playing. Our Hauptwerk Setup:

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

This site participates in the Amazon, Thomann and other affiliate programs, the proceeds of which keep it free for anyone to read.

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed