|

Vidas: Hello and welcome to Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast!

Ausra: This is a show dedicated to helping you become a better organist. V: We’re your hosts Vidas Pinkevicius... A: ...and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene. V: We have over 25 years of experience of playing the organ A: ...and we’ve been teaching thousands of organists online from 89 countries since 2011. V: So now let’s jump in and get started with the podcast for today. A: We hope you’ll enjoy it! V: Hi guys, this is Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 665 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Bob, and he writes, I was just wondering if articulate legato applies to all keyboards or just organs? V: Bob is our Total Organist member, and he asked this question recently. And my short answer was that it is applicable to all keyboards. But there are nuances of course. Not only keyboards. All instruments playing music composed before the 1800s, like violin, flute, trumpet, etc. Unless written otherwise in the score by the composer. What do you think? A: Yes, I couldn’t agree more. I think you answered his question. Short and clear. V: Now we can expand, right? A: Yes, you could a little bit. V: So what’s the proof that all instruments played like that before Romantic Period? A: Well you can check famous treatises written by famous musicians. Of course, we are not talking about organ now, because there are lots of treatises about how to play the organ. But if we are talking about other instruments, because the question was about other instruments, you could read the treatises by Leopold Mozart who was very famous composer and actually educator. We know that he was a perfect educator because Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was his son, but he also was a wonderful teacher of violin, and wrote a very important treatise about playing violin. So you could read that. It has German and English versions for sure, I don’t know into how other many languages it was translated, but you can definitely find it in English. Then if we are talking about flute, then you need to read the treatise by Joachim Quantz. He was a very famous flutist and he worked at the Prussian court. V: So basically, violin treatise by Leopold Mozart applies to other stringed instruments obviously. A: Sure, sure, to all the stringed instruments, not only violin of course. V: And flute treatise by Quantz applies to let’s say wind instruments. I’m not sure about brass instruments, but probably also to some degree. A: Sure. V: So even today, if you watch how string players play a melody, bowing up and down, up and down, up and down - they change the bow. What happens at the instant where the bow is being changed is a micro detachment between those two notes. Down-up. Stronger beats are usually down. So down-up, down-up, down-up - that’s how they play the scale let’s say. If it’s not written legato. A: Yes, and if you are playing of course wind instruments, you need to use your tongue in order to do articulation. V: Tonguing yes. Same with trumpet - also similar. Let’s say with flutes, you play legato only changing your fingering, but with one breath, with one tongue - without any tonguing. But if you play a little bit of tonguing, then those notes are a little bit detached. A: Sure. V: That’s what we would call ordinary touch or articulate legato in keyboard technique. A: Yes, and listening to the early music ensembles, how they perform let’s say cantatas by J.S. Bach, you can hear various instruments that use regular articulation. V: That’s a good question, right? I like when people are wondering outside of their instrument and trying to make connections between other instruments in those periods. A: Sure, and since the organ is also not only the keyboard instrument but the wind instrument, I think we can find close connection about articulation between organ and wind instruments. V: And Bob of course was asking about keyboards in comparison to organs, right? And we’re expanding the question, not only about keyboards but other instruments as well. So Bob needs to know that this articulate legato could be applied to harpsichord, to virginal, to clavichord, what else? A: Yes, to all the keyboard instruments. Except probably modern piano. V: Except modern piano music composed after 1800s. So even playing Mozart let’s say, you could in certain cases play with articulation. A: Yes, definitely yes. V: Right? Probably fast passages of 16th notes. A: Because this knowledge of articulate legato, it existed until I would say Franz Liszt. Don’t you agree? V: Mid-19th century. A: Sure. V: It started to decline during that time, but even Franz Liszt was complaining that in some villages in Germany, they still play with articulation on the organ. A: So, because the tradition was still alive since so many instruments were preserved. I cannot imagine that you would sit down on the Baroque organ and you would play something really legato. V: And in some cases, in some countries, this tradition probably extended even longer, because the instruments remained mechanical with slider chests all the way through the 19th century, like in the Netherlands. A: Yes, you know the poorer church was, the further it was located from the big centers, the better instruments were preserved, because people didn’t have money to rebuild them or restore them, and they basically stayed untouched, luckily for us, that way we know what was at that time, and how the original instruments sounded. V: It sounds like you mean Netherlands were a poor country. A: Well no, but… V: (laughs) A: And actually I was not talking about Netherlands. What I meant more was probably France. V: Yes. France and middle European countries which, for example, have wonderful Baroque organs, not necessarily in the capitals, but in small villages. A: Yes, because like in the big cities if the war would come, all the organ pipes would be made into weapons. V: Yeah, countries like Poland, Czech Republic, Slovenia - there are amazing instruments to explore, and largely unknown to the western world, but they are getting more famous because of virtual organ samples on Hauptwerk. So today you can upload or download those sample sets on your computer and play them on Hauptwerk using realistic sounds from various very exotic countries. A: And it would be really nice to go to visit them, those instruments, and hear how they sound in the real surroundings, and to compare if those sample sets are really as good as you thought. V: What was the first sample set that you discovered, Ausra? A: Velesovo. V: So before that, you probably even didn’t hear, or haven’t heard of Velesovo town. A: Yes, of course I hadn’t. V: Where it was, in Slovenia. And now, if you ever travel through Slovenia or you happen to go with a concert to Slovenia, you would probably look Velesovo up and try to find that church. A: Sure. V: You have a, like emotional connection. A: Because this is one of my most favorite sample sets. V: It sure is. All right guys. We hope this was useful to you. So keep practicing, keep expanding your musical horizons on all the keyboards - not only keyboards, but on stringed instruments, and wind instruments, and brass instruments. This is really fun. And keep sending us your wonderful questions, too. We love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice, A: Miracles happen. V: This podcast is supported by Total Organist - the most comprehensive organ training program online. A: It has hundreds of courses, coaching and practice materials for every area of organ playing, thousands of instructional videos and PDF's. You will NOT find more value anywhere else online... V: Total Organist helps you to master any piece, perfect your technique, develop your sight-reading skills, and improvise or compose your own music and much much more… A: Sign up and begin your training today at organduo.lt and click on Total Organist. And of course, you will get the 1st month free too. You can cancel anytime. V: If you like our organ music, you can also support us on Buy Me a Coffee platform and get early access: A: Find out more at https://buymeacoffee.com/organduo

Comments

Vidas: Hello and welcome to Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast!

Ausra: This is a show dedicated to helping you become a better organist. V: We’re your hosts Vidas Pinkevicius... A: ...and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene. V: We have over 25 years of experience of playing the organ A: ...and we’ve been teaching thousands of organists online from 89 countries since 2011. V: So now let’s jump in and get started with the podcast for today. A: We hope you’ll enjoy it! V: Hi guys! This is Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 606 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Laurie, and she writes: “Hi Vidas, Be sure you are sitting down to read this. ? I have no objection to the study of articulate legato touch for early music, but my question is, why MUST we use it? I understand it was the practice in the time of Bach and early music, but wasn't that true because the tracker instruments lent themselves to that sort of touch? And the flat pedalboards could be navigated easier with all toes, rather than using heels. But if we have a modern instrument that does not have "tracker touch" and has a concave radiating pedalboard, why not lend new interpretations to these masterworks? It could give new life and new understandings to old music. I'm sure you have heard Cameron Carpenter play. I'm not always a fan, but I learn something new about the construction of the music when I listen to his interpretations. For example, here he is playing the Bach B Minor Prelude and Fugue on a modern organ, making full use of colorful registrations and expression pedals. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jixCGS_AAG8 Isn't this improvisation in its own way? What do you say?” V: And by the way, Laurie is on the team of people who are transcribing these podcast conversations, so she’s also, then, a member of the Total Organist community as well! So, Ausra, what comes to your mind when you’ve listened to this? A: Well, of course you are free to choose. You live in a democratic country, and you can interpret music as freely as you want, but if you are thinking that this is something new, to play Bach legato and on a modern instrument, this is not a new way, because that ordinary touch about which Vidas and I are talking and advocating so much, actually it was sort of recreated and rediscovered, and only, I would say, 40 years ago, maybe, if I’m correct. And it all came with people like Harald Vogel, who advocated to play the Baroque music on the Baroque instrument and early music on the early instrument. And how I see things is that after you try to play it in the ordinary touch and using only toes for the pedalboard, you will never go back to playing otherwise. And the advantage of what we are advocating is this: If by chance in life you will get access to a historic instrument, you will be able to play it, and if you will only use only modern techniques and play Bach legato and use your heels while playing Bach, you will never be able to play on the historical instrument, because you will sit down at the organ bench, and you will see that it’s simply impossible. Okay, let’s hear what Vidas thinks about it! V: I have a few things to say. I think if Bach lived today and played those modern instruments, he might have written a completely different kind of music, right? And not necessarily in his own Baroque style. He might not have been an organist at all in this day and age. Right? It’s very idiomatic to his period that he became what he became, actually, and not even talking about Bach, but any other master from the past. So, when we encounter masterpieces from those days and we try to recreate how they might have sounded today, we always make some compromises, because when we are on a modern instrument, we don’t have those sounds available, or even the intervals available. The tuning system is different, and then we’re hearing a little bit different harmonies—not as pure, for example, not as colorful. But then the advantage to the modern era is that composers can modulate to any key they want and each key sounds exactly the same. It’s from the color perspective, but it kind of ties to this performance practice, and in forming performing practice, we’re not advocating that you should necessarily play everything with toes only, but you should know how it’s done, and then you are free to choose, and not only know, but I think you could try and practice and spend some time, and when you master one, two, three, or five pieces this way, try to do an experiment; try to learn something else from this period but in a legato fashion, with heels, for example. Try your own pedaling and fingering with finger glissandi and everything, and then go back to this historically informed technique in the way you play it, and see if it sounds more convincing. You see? The style of music lends itself to this kind of articulations, and if you use modern pedaling, you have to think about articulations. But if you use early pedalling and fingering, then it works automatically. You can recreate it automatically. You don’t even think about it. A: Well, and as I mentioned before, don’t think that what Carpenter does, that this is a new thing, because Marcel Dupré actually toured America many years ago during his lifetime, and he plays all Bach, complete works by Bach, and I believe he even played from memory, and of course, he used the legato techniques and toe and heel techniques on the pedalboard, so it’s nothing new, what you are talking about. Well, okay. V: And so, just try different approaches and then choose the one that sort of works for you in your situation. We just don’t want you to relearn the same piece twice. If you ever have the chance to play a tracker instrument, which was inspired by Baroque techniques, or an actual Baroque organ if you go to some church which has… some organs in the United States have historically based organs… and you might have a chance to play them, and what would you do then? Would you play legato, or would you try to relearn it the second time? We advocate that you don’t have to relearn it. You can do the same thing the right way right away, and then it would sound convincing on any instrument. The last thing, Ausra, if we consider this. If you play with articulation on a modern instrument, does it sound bad? A: Well, no, it doesn’t sound bad. V: Does it sound bad if you play with toes-only technique on a modern pedalboard? A: No, I have never noticed that. V: But the other way around, if you play on a historical instrument and you play legato, does it sound less convincing? A: Sure! Definitely. V: You see? It’s kind of self explanatory. This technique doesn’t go both ways. You can play with articulation and with toes only on any instrument, not only with a Baroque instrument. But when you go to the Baroque instrument, legato technique doesn’t work so much. I mean, there are some instances and exceptions, but in general the rule is articulate legato like string players would articulate with their bows, or with their tongues for wind instument players. Flutists, for example. A: Yes, I think that’s a very good insight you are talking about. V: Alright, guys! We hope this was useful to you! Please send us more of your questions; we love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice, A: Miracles happen. V: This podcast is supported by Total Organist - the most comprehensive organ training program online. A: It has hundreds of courses, coaching and practice materials for every area of organ playing, thousands of instructional videos and PDF's. You will NOT find more value anywhere else online... V: Total Organist helps you to master any piece, perfect your technique, develop your sight-reading skills, and improvise or compose your own music and much much more… A: Sign up and begin your training today at organduo.lt and click on Total Organist. And of course, you will get the 1st month free too. You can cancel anytime. V: If you like our organ music, you can also support us on Patreon and get free CD’s. A: Find out more at patreon.com/secretsoforganplaying

Vidas: Hi guys! This is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 547 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by J. Flemming. He writes, Although my teachers have stressed the importance of articulate legato in playing Baroque music, I was never taught early fingering, so it is very easy for me to lapse into familiar patterns (like crossing my thumb underneath my fingers). I am learning BWV 659 (ornamented chorale Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland) with Vidas’ fingering, and it is taking more repetitions to get used to the fingering. The results will be worth it, though. I expect to be able to play this in a service before Advent is over. It’s been a good exercise in developing the discipline to do it right instead of quickly. So, this question was sent before Advent was over, obviously. A: Sure. V: And now we’re talking after Christmas. Okay, it’s very nice that J. Flemming is using my practice score of Nun komm der Heiden Heiland. In this particular score, I really take advantage of early fingering in the left hand, where you have two voices, alto and tenor voices combined. And also, in the soprano part, where there is one ornamented, highly ornamented melodic line. And in the pedals as well, even though they move slowly, I don’t use heels, I don’t use substitutions, in the hands also, no substitutions, and no thumb glissandos, things like that. A: You don’t need glissandos, because you play everything in detached manner, articulate legato, so… V: At first, it sounds strange, right, Ausra? A: What? V: This type of articulation. Or not? When you first started, what was your experience with articulate legato? A: Actually, it was like discovering America for me. Because here nothing sounded swell while playing baroque music, and sort of half-articulate way or legato way. Because instrument itself wouldn’t speak if you would play legato. V: Mm hm. For me, I couldn’t discover this articulation for a long time. Even though my first teacher sort of taught me this. But, it was very complex explanation. I couldn’t get the basics right. And plus, of course I was very young, and you had to understand something differently. A: I don’t think your first teacher understood the manner of articulation very well, too. Even in the Academy of Music, there was none that taught articulation really well. We had some sort of understanding about it, but incomplete and insufficient. And incorrect in many ways. Because if you would look at the Academy of Music at all our professors, and you would look how we play the pedals, how we are pedaling Bach, it’s just horrible. Remember when we went to Eastern Michigan University, and our professor, Pamela Reuter-Feenstra, saw our score that we brought from Lithuania, and it was with the fingering and pedaling, by your professor, Leopoldas Digrys, she just thought to throw that score away right away and never come back to it. V: Or put it into a museum of incorrect fingering! A: Yes. So, basically, so I guess the right understanding of why this articulate legato and fingering and pedaling is needed, came to me when I tried, basically historical instruments, and especially the pedal clavichord. V: Yeah, instruments themselves can teach you a lot. Probably more than any teacher can. Although, I understood the basic articulate legato principle easier, I think when I started studying fromRitchie/Stauffer method book. Because he gives this exercise to play with one finger, as legato as possible. But since you are only playing just with one finger, it’s not really legato. And then repeating the same articulation with all the fingers. Sort of imitating. And then it clicked for me. All the voices have to play this way, even though you are using all the fingers. But if you are not sure, play with one finger only at first. A: But developing this technique, it takes time and patience, of course, too. I think every time when you practice organ, you need to have patience and you really need to listen to what you are doing very carefully. Because it’s basically an art to be able to play baroque, romantic, and modern music, especially if you have to do that all in one recital. V: And if you’re a beginner, those three styles can mix in your head, right? But it’s very, I think healthy to work simultaneously in three different styles: early music, romantic music, and modern music. Because the more you do it, the more easily you can switch between them. A: Sure. V: Right? A: That’s right. V: And the longer you play with one style, the more difficult it is for you to switch, right? Especially if you are a beginner. You get used to one particular style. Let’s say you’re playing Bach chorales all the time. Or let’s say short preludes and fugues, from the famous Eight Preludes and Fugues collection. And you don’t play anything else, and if you suddenly start playing a romantic piece or a modern piece, it doesn’t feel natural, right? A: Sure. V: You have to switch, like between having three different cars, or five different cars, or twenty cars...the more the better! A: I would say it’s probably not switching a car, but like switching from a shift stick to the automatic. V: But cars are also different between themselves, between mechanical and mechanical - different models, right? So how your foot feels on the pedal is different. The wheel also is different. And the gears shift differently a little bit in each car. But car mechanics don’t have any trouble because they have tried them all. A: Yeah. V: Ok guys, this was Vidas A: And Ausra. V: Please send us more of your questions. We love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice, A: Miracles happen.

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas!

Ausra: And Ausra! V: Let’s start episode 517 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Lee, and Lee commented on the YouTube video of mine where I talk about articulate legato touch in early organ music. I demonstrate how it sounds vs. normal legato. Normal legato is when notes are connected, and articulate legato are where there is some detachment between the notes. Right? So he asks: “"How would "articulate legato" be notated in a score vs. normal legato? Thanks."

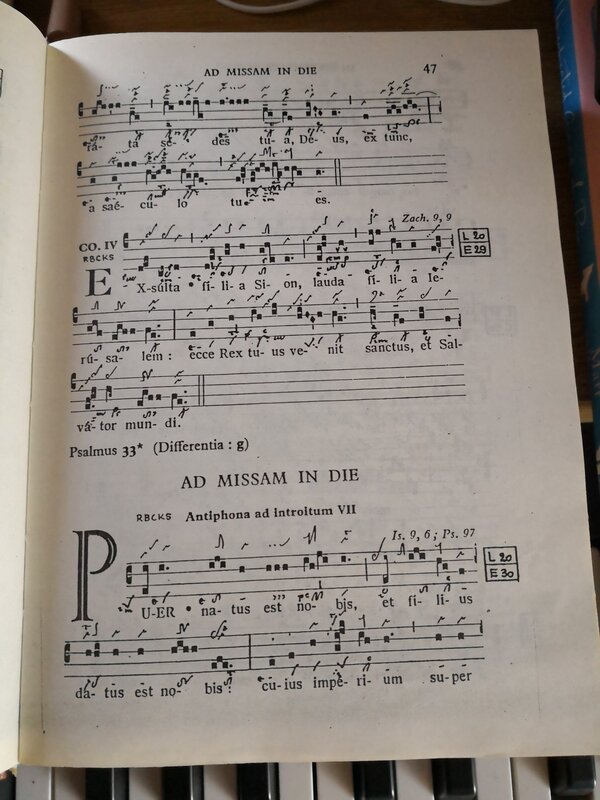

A: Well, this question makes me smile a little bit, because articulate legato is supposed to be played for… it’s intended for Baroque music, for early music. So, if you are playing, let’s say, a piece by J. S. Bach, or Dieter Buxtehude, or other early masters, you simply know that everything that is written, and it’s written in a normal score without any articulation marks should be played in articulate legato.

V: Right. But… A: But…. You only play legato whose parts are specifically written in. V: Ah, I see… A: Plus, you need to find a good edition. It means, if you will pick up, for example, an edition made by Marcel Dupré, you can simply just throw it away, because it’s all marked in legato and other articulation marks, but these are not original. These are added later by Marcel Dupré. V: Yeah, and Marcel Dupré legato fingering and pedaling are dated. They are basically not used in historically informed early performance practice style. We don’t, of course, have CD recordings from the Baroque times. A: From the 17th and 18th century! V: Yeah. But remember, Ausra, we do have, for example, several pieces recorded on a mechanical clock from the 18th century—Handel’s Concerto, for example—with multiple virtuosic embellishment. A: Yes. That’s right. Plus, you know, the greatest evidence that we have are surviving instruments. Simply, if you would play legato on the Baroque instrument, it wouldn’t work. V: And we just have to look at other instruments which share the same articulation. Strings, winds… A: Yes, and you know, we have also many treatises from that time survived about playing various instruments, not necessarily the organ, but let me just mention, probably, the few famous ones such as C. P. E. Bach’s “The True Art of Playing Klavier,” then the big book of Joachim Quantz on playing a flute, then Leopold Mozart on playing violin, and basically, if you would read all these books, you would find the sections talking about articulation, and you will see that baroque music was all about articulation. V: And similar to keyboard, string music, like violin music, also had a similar articulation done with bowing. A: Yes, and the bow itself was shorter than it is in a modern violin or other stringed instrument, so obviously, you had to articulate much more. V: Exactly. And you know, when you change the direction of the bow, there is a slight break between those two notes, and that’s what creates this ideal articulation! A: Yes, but for many beginners, when they start to articulate baroque music, they simply start to play it too detached. It sounds just like staccato, and it makes me laugh, because it really sounds like a comedy. V: Artificial! A: Artificial. It’s not like it needs to sound. V: The principle is that you sort of play with one finger but as legato as possible. A: So basically, to master this ordinary touch, it takes time. It takes time, and it takes effort, and it takes to listen carefully to what you are doing. You cannot do it in one night, or in one year, I would say, too, unless you are really sufficient in your practice. V: What about the wind instrument, tonguing? Is it also similar, too? A: Yes, it’s very similar. V: ...to what we do? A: Practically, they had to tongue each single note in most of the cases. V: Unless it’s written “legato.” A: Yes, that’s right. V: or staccato. Then it would be shorter. A: And wind instruments and organ have so much in common, because they both have pipes. So, I guess this also suggests to us that the correct way to play Baroque music is to articulate it. V: So guys, if you want to find out more about articulation of early music, check out those three treatises. We will link them in our description of our conversation—the one with the treatise by C. P. E. Bach about playing keyboard instruments, basically Klavier, as he says, and the next is by Joachim Quantz about playing the flute, and the last one is by Leopold Mozart (Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s father) on playing violin. A: Yes. V: And those three treatises, will give you a great, great introduction, not only to this idea of ordinary touch, or as we call it today, articulate legato, but also to all kinds of performance practice issues including fingering, ornamentation, for example, diminutions—all those details that make your Baroque piece sound like it might have been performed back in the day. A: Yes, and the biggest counter argument that I heard about why we need to do it nowadays, they most simply are the modern instrument and so on and so forth, but even if you play articulate legato on a modern instrument, it still sounds better in this kind of music, at least for my ear. V: Obviously, yes! It’s more difficult to articulate on a modern instrument, because the keys are wider and longer, and the feeling of the keyboard is different. Right? But if you apply this ordinary touch right away, you don’t have to relearn it if you ever have a chance to practice on an historical instrument, or a copy of the historical instrument. A: True, and that’s what I think it is that separates just an ordinary musician from an excellent musician, is that you learn in time. Because, for example, the older generation, for example our professors, Quentin Faulkner and George Ritchie, they had to relearn it, because as young people, they were taught to play legato, and to do only some articulation in Baroque music. But later on, all this big discovery basically based on German organists such as Harold Vogel or Ludger Lohmann became famous throughout the organist world, and some of the older generation didn’t want to accept it. I have met some of them personally, and they would be complaining, “Oh, there are these youth that nowadays play all Bach non-legato, and they call it ordinary touch, and they say that this is the way that Bach played...” V: And this youth was over 50 years old! A: Yes, but that guy who told me that, I think at that time he was more than 80 years old already. He was a pupil of a famous German organist, Karl Straube. V: Yes. A: And Straube was the same in Germany at the time as Marcel Dupré in France, so really a leading figure. And of course, he taught this guy that I knew to play legato, and he trusted him because he was such a renowned organist who worked widely in his days. But life is changing, and new discoveries are made. So our professors, Ritchie and Faulkner simply relearned everything. V: Yeah, and as long as you keep learning, you postpone the aging process, which is really good news. A: And anyway, when you hear one performance and another one and you compare them, then you know right away which is the right one, because your intuition tells you that. And after trying that ordinary touch, you will never go back to playing Bach legato. V: Thank you guys, this was Vidas, A: And Ausra. V: Please send us more of your questions; we love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice, A: Miracles happen! Today I had our 3rd Unda Maris organ studio rehearsal this year. The church was rented out for some event so we played at the Aula Parva on a single manual Baroque organ with pedals. There were 6 people present - Diana, Grazvydas, Karolina, Franziska, Rokas and Justas. All but Diana and Justas are starting to play the organ only this year. One lady went to the church instead and didn't find my message in time. A couple of other students wrote to me saying they couldn't make it today.

Diana had to leave the earliest so she started the first and played a chorale "Wer nur den liebe Gott lass walten" by Johann Ludwig Krebs (2 outer voices only). I recommended she start feeling the pulse to get the music flowing. Grazvydas brought a little Prelude and Fugue in G minor, BWV 558. I taught him to use articulate legato and play with one finger only to discover the ideal touch. Karolina at first started to play a hymn but she didn't have the music and really could handle 4 part harmony. Instead I asked her to play the 1st Short Trio by Jacques Nicolas Lemmens. I wanted her to start practicing in 7 different combinations for the next time. Franziska also played the same trio but I wanted her to shift her body position easily by pushing off with the right foot when the melody moves downward and with the left foot when the melody ascends. She discovered the need for organist shoes with heels. Rokas brought the Three Part Sinfonia in F major by J.S. Bach. Since he used a rather antiquated edition, I recommended he ignore the slurs and play the mordents from the upper note. For the next time he should also choose one of the Little Preludes and Fugues to work on. The last was Justas who showed to Rokas the little Prelude and Fugue in A minor which he played last year. Maybe Rokas will pick that one. Justas also played one piece from some movie arranged for manuals only. He added his own pedal line. I'm looking forward to our rehearsal next week. Tomorrow I plan on creating a special team for Unda Maris on Basecamp for internal communication because I've noticed how inefficient email is (I can't even find my Unda Maris list on the phone so I'm stuck to either responding to earlier messages or writing on the laptop which not always is possible, like today when I had to change the place of the rehearsal on a short notice.)

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 283 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by William. He wrote: Hello again! Question. I am working on some choral preludes from the Orgelbuchlen. When there is a melody separated from left hand and pedal, do you articulate all of the parts? Thank you. William V: Let’s imagine if I understand this question correctly. What’s your idea, Ausra about this situation? A: Well of course you have to articulate all parts because that’s what baroque music does. You need to play them articulated. V: When then is a melody separated from left hand and pedal. Ah, he means… A: He means like for example chorale like Wenn wir in höchsten Nöten sein. V: With ornamented cantus firmus. A: Yes, when you have ornamented cantus firmus most often in the right hand. Sometimes you could have it in the left hand in the tenor in more advanced chorales and yes, you need to articulate all parts. V: And I see why he has this question, right? Because if the top voice is so important and melodically ornate and beautiful maybe he thinks that this is the voice he needs to articulate and other parts are not that important like accompaniment. What I’m thinking is more of playing with four different instruments. How about cantus firmus playing with oboe, then maybe alto with violin, tenor with viola, and then the bass with bassoon or cello or even doubled with double bass. So all those different instruments should do some articulation Ausra, right? A: Yes, that’s right. V: Because they are doing dialog and duets with each other and commenting on each others musical ideas. A: And to give you more ideas how baroque music should sound, how it should be articulated, I think you need to listen to some recordings of Bach cantatas and his instrumental music. There are so many nice recordings on YouTube that could give you a clearer idea of how things worked in baroque times. And then you will see that each voice is important. V: When violin plays for example a passage, unless it indicated legato, they would make an articulation with bowing. Down, up, down, up. And this short instance when the bow is changed is an articulation. A: That’s right. You know especially when you have ornamented chorales like William mentioned in his question. It’s only a question of how much you need to articulate and it depends on what kind of instrument you are playing, what kind of acoustics it is in, and you need also to vary articulation between your hands and your feet. V: Umm-hmm. A: Because if it’s cantus firmus or solo voice it’s very ornamented you probably will articulate it a little bit less because you have many diminished notes with small note values and of course you will play that voice a little bit more legato but not legato still, quasi-legato. V: People downstairs will think it is legato but upstairs you will make articulation. A: That’s right. And then probably the bass line and your left hand you will have to articulate a little bit more. V: Umm-hmm. Because they are moving in longer note values. A: Sure, and especially bass line because obviously you will be using 16’ stop in the pedal. V: And the bass usually moves in eighth notes that way. Imagine cello playing different bowing, right, left, right, left. That’s also articulation for each and every eighth note. And then for example if you are imitating a wind instrument like oboe, it’s done with tonguing too. Takka, takka, takka, takka. With trumpets, I don’t know. Or with oboe or something similar. Baroque articulation was called “ordinary touch” and it was so common that people or composers didn’t even notate it on the score. A: Sure, because it was the common tradition and everybody knew it. V: Umm-hmm. What they did notate is when articulation was different like legato or staccato. A: Yes, those few places where you have to play legato they will be indicated in the score. V: But checking the score is original, not edited in modern times. A: Well I think that in modern times many editors use legato in baroque music. I think this was common in the period of late 19th century and early 20th century. So those are the most dangerous editions to look at. V: Umm-hmm. Excellent question that William has sent, right Ausra? A: Yes. I would never even think about it myself that these kind of questions could arise but it’s fascinating, it’s truly fascinating. V: You know what is self understandable for us, like second nature. For a lot of people who haven’t played for 25 or 30 years like we are doing. It’s really a mystery sometimes, a secret. So secrets of organ playing, that’s what we are revealing. A: Yes and actually this kind of question makes you to look at the various issues in a different angle, in a different light and a different perspective, and it’s fascinating. V: You know this organ technique book by George Ritchie and George Stauffer that we so often recommend and use in our teaching, George Ritchie writes about early music articulation and has some exercises there. He writes that if you want to achieve articulate legato with five fingers, first try to play the same passage with one finger, second or third finger and do it as legato as possible. It should not sound too detached. Instead aim for a singing manner, cantabile manner, as legato as possible with one finger and then try to repeat the same thing with five fingers. Normal fingering. That’s articulate legato. A: That’s a good exercise that you are telling. Everybody needs to try it. From my experience with my students and probably with myself a long time ago, I could see that when you are starting to learn baroque articulation first of all you are playing everything too legato because it’s hard for you to articulate each note. And after that it comes the second step where you are playing everything separately but your articulation is too short, everything sounds almost staccato and soft of almost un-musical and very unnatural. And after this one you sort of start beginning to regulate everything. And then it becomes as it should be, neither too short nor too long. V: So the first step is to play too legato, the second step is too detached, and the third step is sort of in the middle. A: And it’s sort of very hard to overcome each step. You cannot jump right away to the last one. V: What’s the next level after you have mastered this? A: Well, I don’t know. V: Now, today you are not even thinking about that when you are sight-reading even, right? A: Yes. V: What do you think about instead? A: Well I think in general more about the meaning of the piece, about structure, about all those things. V: About how the piece is put together. A: Yes. V: Harmonies. A: Yes, and if it’s choral based work you think more about text painting, about all those baroque rhetoric figures. V: Right. A: About instruments that piece was originally composed on. V: Interesting. So each level of advancement has its own advantages and disadvantages and short-comings and also benefits. Remember we also have to go to a beginners mind in order to understand how other people feel and sometimes we forget how we started, right? I remember that articulation was a mystery to me for I don’t know how many years. At least probably five years. At least probably until we met Pamela in Michigan. A: Yes, for me it was really a mystery until I tried a pedal clavichord. I think that the pedal clavichord finally taught me to articulate. V: And that was in Sweden in 2000. A: Yes. Sometimes you can cheat on the organ actually, and cover things up about playing the organ but you cannot do it when you play a clavichord. You will not hide anything. V: And knowing that the clavichord was regular practice instrument for organists back in the day then it reveals you all those secrets. So Ausra, final advice for everybody listening wouldn’t it be wise to travel a little bit more and try out as many historical instruments as possible. A: Yes, if you have possibility of travel. If you don’t, then try to listen more to historical recordings, made on historical instruments. It will give you a pretty clear idea. V: Wonderful. Thank you guys for sending those thoughtful questions that we sometimes don’t think people encounter those problems. Apparently they do and we’re so glad to help you out. And keep sending them more and we will try to help you advance in the future. This was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: And remember, when you practice… A: Miracles happen. Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 156, of #AskVidasAndAusra Podcast V: This question was sent by Monte. He writes: "Maybe one day you could create a course revealing how you decide to articulate legato fingering for the Bach scores that you recently made available. It’s kind of mysterious. The Ritchie and Stauffer organ technique book has a lot on this, but having you explain and demonstrate adds a lot of value." V: That’s an interesting question, right Ausra? A: Yes, it is. V: We have talked a lot about the principles behind early music fingering, but we haven’t created a step-by-step course on this, right? Like, for example, what Monte probably means, is that the camera would point somewhere from our shoulder, right? And as we are playing it, this choral or music order let’s say in this case Bach music, the camera would point to our hands, right? And then as we’re playing, we should probably demonstrate and explain the changes of the fingering we’re making. A: Well, yes, and I would like actually to separate these things; you’re talking about Bach as early music. I would not call Bach music early, and I would not use fingering in Bach music. For example I use when I play, let’s say, really early pieces, Estampie Retrove from Robertsbridge Codex, or Faenza Codex or really early stuff. Because Bach music is already such a complex music that you can not sort of use only early fingering. For example, in many cases you have to use the thumb or the black keys or accidentals, yes. V: I think you are right Ausra, because simply this of fact; Bach uses many more accidentals. A: I know, and the more accidentals you have, the more you have to use things like thumb under, or thumb on the accidentals. And all kinds of tricks, and you know what I think Monte is talking about is that he wants to get from us some sort of a system. But I don’t think that there is complete system that you can apply to any given piece of music, because each music even by J. S. Bach is so unique that sometimes you have to have unique solutions. V: And I fully agree with you. I just want to add of course I’m talking about Bach because that’s what Monte is interested in. And we’re talking about early music. And the only thing that I wouldn’t do with Bach in comparison to real modern music or romantic music is probably finger substitution and glissando. A: Yes, that’s definitely. V: You could get away without that. A: Sure, sure, you wouldn’t want to do that in Bach. V: Even when you have two voices in each hand, you could still play without finger substitution, I think, in most cases. But there are exceptions, there are exceptions, even in Bach. So remember we could each talk a little bit about our experience in playing E flat Major Prelude and Fugue, because you are practicing it currently for the upcoming Bach birthday recital. And I, this morning, actually recorded a video with the camera pointing right above my hands so that my transcribers could transcribe fingering and pedaling from this video played at a very slow practice tempo. And probably this score of E Flat Major Prelude and Fugue by Bach BWV 552 will soon be available if you want to master this piece without much frustration in figuring out your own fingering, right? So Ausra, do you use a lot of thumbs on sharps and flats, lets flats because it’s E Flat music? A: Sure. Not a lot but I use some definitely, yes. You cannot avoid that especially when the texture is so thick. If you would think about the first fugue, for example, there are two lines that are just killing me in that fugue, the ending of it and then ending of the first half of it. It’s really very complex. Sometimes I just feel that I’m playing with both my hands fully with all my fingers at the same time because of the thick texture. Don’t you get that feeling? V: Absolutely, it’s a five part texture. A: Sure. V: Right? And I can guarantee, that if you wrote down your fingering, or somebody recorded you playing this piece from above, right, and if our transcribers would transcribe your own fingering and compare it to my own fingering, it would not necessarily coincide, right? A: Yes, but, V: And the learning also choices might be different. A: Well, I think on the pedals we would agree more than on the fingering probably. V: But when fingering gets very individual because the hand layout for each person is a little bit different, right? And the span of the palm is different for each person. You can, I don’t know, can you reach a tenth? A: Some of the times I can reach with my left hand, not with my right hand. V: Right. So, there are people that can hardly reach an octave. A: I know. V: So then they figure out some other ways to play those middle voices. Maybe they sometimes migrate from hand to hand. A: Yes. For example, composers like Cesar Franck, he had such a wide hand. I was already, I almost forgot about it but recently I started to play sort of the second chorale in d minor by Cesar Franck which is probably my most favorite piece written by him. And sort of I remember how wide some of the intervals are. And if you have that Dover publication of his complete organ works, it has a picture of him. V: The famous painting. A: Yes, and you can see how wide his hands are. And in pieces like Choral No. 1 in E Major and in his Priere and his 2nd Chorale in B minor, those intervals are just enormous. And you just have to do transfers with one hand, at least. V: It might not be a painting but every photograph of him. A: Could be, could be, yes. V: So going back to let’s say, example Bach’s BWV 552, we have talked about importance of placing the thumb on the black keys. Of course sometimes even in this advanced E Flat key, we have instances when you could play with early fingering. Let’s say if you have parallel Intervals of thirds or sixths. You easily play thirds with 2-4, 2-4, 2-4, if they’re not too fast. Or the sixth could be played 5-1-5, and 5-1-5. Don’t you think, Ausra? A: Yes, there are places like this. But of course another thing which is very important when practicing this piece or any other Bach pieces that has multiple voices, that you have to know which hand is playing which line. Because it would be very easy, that’s why I like trio sonatas so much, that you have a single voice for each hand and one voice in the pedal. And you always know that is that way throughout the piece. But in a piece like E flat Major, Prelude and Fugue, you know sometimes you have to pickup a line from the bass line and play with your right hand, and sometimes you have to pick up some music from the treble clef and play with your left hand. And it’s very important to mark you score in those particular spots. V: Before. A: Before writing down anything. V: So, when you write down fingering for yourself, do you notate divisions of the hand for the entire piece or go page by page? A: Well I do it for the entire piece because it’s very important. V: I have a different method because I’m very lazy. I tend to have a short attention span and I only can focus at one page a time. So when looking at one page at first, I divide the hands, and look at the places where my middle voice and my great from hand to hand, notate it in pencil, or if I’m doing this on the computer, I do this directly on the computer. And only then I would add fingering, right, for that particular page. I don’t go to the next page right away. So Ausra, do you think that this system is better than yours or not? A: I don’t know, it just depends on what your character is, or how long can you stay focused. I think the result would probably be the same. V: Of course, but still you will need fingering, right? You will complete the fingering whether you are working for one page at a time or the entire piece. A: Yes, and for doing this division thing you have to sight-read the piece at the beginning to feel both hands. We often talk during our podcast, that you have to learn things in combinations and start to play everything together, right at the beginning. But you have to sight-right a piece first, with both hands and probably both feet. And this doesn’t matter that you may play half of the notes wrong. But when will you get to know the understanding where you will have to do the division between your hands. And after that you can write down correct fingering. V: Well actually, if you make too many mistakes, then it might mean that this piece is too difficult for you at the moment. A: Yes, that’s true. Because when you sight-read the piece through it gives you sort of an understanding how long it will take for you to learn it. Not to that final stage. V: What do you mean Ausra? Do you have a system, a precise system of calculating the number of repetitions? A: Well, no. But I sort of have a right intuition for things like this. V: Let me say that I have a system that might work for you and it might not work for you, or other people, but it works sometimes for me. Whenever I play the piece and I sight-read it at a concert tempo, and I make mistakes, I have to record myself, and then play back that recording, and mark the mistakes on the score. And then I will count those mistakes and that will tell me how many repetitions do I need to play, because with each repetition, I usually master one mistake. Is this realistic enough, Ausra? A: (Laughs). Well you know, yes and no, because mistakes are different. Sometimes you can just hit the wrong note but sometimes it might real technical difficulty. But you need many different repetitions to overcome. V: So but I mean of course you have to sight-read it at the concert tempo while recording yourself and counting mistakes. A: Is this possible to sight-read each piece at recital tempo? V: Everything is possible but the result might be something you want to hear of course. A: Yes. Try for example, one of Reger’s fantasies, chorale fantasies, and look how it works. For example, Fantasy on BACH and play it at concert tempo. Good luck with that. Have fun. V: That simply means probably that you need to have many hundreds of repetitions. A: That’s true. V: It’s all about numbers guys. And math is our best friend. Thanks for listening, and remember to send us more of your questions. We love helping you grow. This was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: And remember, when you practice… A: Miracles happen! VIDAS: Hi, guys. This is Vidas.

AUSRA: And Ausra. Lets continue our discussion from yesterday about articulation in baroque music. Listen to the audio version here. A: You just not play like non legato, but you know you think about the meter, you think about strong and weak beats. V: But that is another level of sophistication, right? A: Certainly. V: Not every note is full of value then and in duration but before the strong beat you are to play it more. A: Yes, that is true. V: Or before the relatively strong beat such as the third beat in the 4/4 meter. You also articulate a little bit more than before the second or the fourth beat. A: Yes, that is correct. And you know I believe it’s hard for people who were studying in their youth to play Bach legato and now they have to relearn it. And George Ritchie and Quentin Faukner, our professors we were both taught to play legato Bach when we were young. And we had to actually to adjust and to relearn it and they just succeeded in doing that so well. V: So what does it tell you, Ausra, what qualities should you retain even if you age. A: Well I think you still have to retain a high quality V: I mean, quality in your character; if you all the time, all your life have learned a certain way, right, and then styles change with times, and you still continue to play in a certain way you are sort of left behind, right? So what I mean you should stay curious about new developments in your research. A: Yes, certainly. Don’t trust that old saying that an old dog cannot learn new tricks. That is probably not true. I am talking about us, in general, you know people, human beings. V: Yeah, we can learn new tricks all the time. A: Yes, and if you don’t trust us, play or listen to different recordings when Bach is played legato, and when it is played non-legato. YouTube is full of excellent recordings. V: And listen to baroque violins... A: Sure! V: Bowing, down, up, down, up. At the instant that the player changes the direction of the bow, there is a very short, almost imperceptible silence, but that is articulation. A: Yes, that is true, yes. V: So it should be a singing manner, cantabile manner of singing, such as Bach described in the title page of his 2-part inventions. Don’t play in a choppy manner, but try to physically sing the parts. That is a good practice too. A: Yes, I think it takes years and years to master all the baroque articulation. It’s a separate world within the organ world. V: And if you want to master it easier, then simply apply early fingerings, right? A: Sure. That helps too. V: We try to help you by providing you with early music scores like that, so that you have instant fingering and further linking your organ pieces. You can start practicing right away almost without thinking. It’s given, it’s almost automatic because it works in a way that the fingering will produce perfect articulation. A: Yes, it helps. It means that if you choose your pedaling and fingering correctly then you don’t have to worry so much about articulation because it is automatically done. V: Wonderful. And of course if you compare organ with wind instruments, there is another similarity, right? Like tonguing. Each not is also articulated, unless they are playing legato. A: Yes, that is correct. V: Like tah tah tah tah tah. Each note is articulated in, let’s say, oboe or flute, and trupet players do the same in their way. So it was a widespread practice, across the board, in all musical instruments, in the music composed, I would say, up until the 19th century. A: Yes. V: Or even sometimes into the 19th century, right? A: That is true. V: Remember the famous saying of Franz Liszt, which he spoke while he was traveling through the villages of Germany, and that he was amazed that some people in those villages were still playing with an articulated manner in the middle of the 19th century – which means really that this articulated legato did not go out of fashion overnight on January 1, 1800. Someone decided ‘no, no, no, you should be playing legato and suddenly they began playing legato. But it was a very gradual process partly dictated by the composers together with the instrument builders, because the style of instruments changed, and the style of music changed as well as the fact that the style of composing also had changed. It was similar to opera and piano music, really, and symphonic music. That is how legato touch came into fashion. A: I know, and this is a reminder that we must choose our music appropriately to fit our instrument. If you are working on a baroque instrument don’t choose music by Reubke. If you are playing on a Walcker organ or a Cavaille-Coll organ then don’t play Estampie Retrove from the Robertsbridge Codex from the 14th century. V: I remember my first mistake in articulation when I was in the 10th grade. I was just starting to play the organ, and my first organ teacher had me choose one of the chorale preludes from Bach’s Orgelbuchlein. And she reminded me that you should use articulation between the voices. But at the age of 16 what did I understand about articulation? So for ten years before that I was taught to play everything legato. I could not simply change my playing style overnight. So over the course of two weeks I learned some episodes of that chorale prelude – I believe it was Jesu Meine Freude – and it was all legato. My first teacher was infuriated over that and said ‘you should not have even played this piece at all over those two weeks. Now you have to relearn it and it will take you months to change your playing style.’ So guys remember to think about the correct articulation from the start. It pays off in the future. And remember: when you practice... A: ...miracles happen. Articulate legato traditionally was called the Ordinary Touch in the Baroque period. Composers seldom wrote in articulation marks in the scores. Instead, everyone knew how to perform - all the notes should be slightly separated unless notated otherwise. The distance should not be wide, just enough to hear the articulation. Bach referred to such manner of playing as Cantabile style. It's like playing a violin - we don't hear the rests between the notes but the bow is moved up and down. Wind instruments also have this tonguing technique - a silent "tee" is made when the tongue strikes the reed or roof of the mouth causing a slight breach in the air flow through the instrument. That's why we use articulate legato when playing early music on the organ. Ausra's Harmony Exercise: Chromatic Sequence in F Major: I-V64-I6 When we play early music (composed approximately up until 1800s) on the organ or on any other keyboard instrument, the general articulation is articulate legato or the Ordinary Touch as it was called in some treatises back in the day. Some people take it to the extreme and begin to play more like non legato. The result is not quite what they would want but sometimes they don't know what the problem is.

It turns out that too detached articulation makes a negative impact on the flow of music. The piece begins to sound as if we play counting from beat to beat or worse, from note to note. There is one way to find an ideal articulate legato (even in the middle voices) which Dr. George Ritchie talks about in his Organ Technique method book - play a passage of music using one finger only (2 or 3) of either hand but as connected as possible. In other words, try to play legato with one finger. It's not glissando, though. Bach would call it the Cantabile (singing) style of playing. When you listen to this passage, repeat it using a normal fingering but keeping the same style of articulation. Another way to find an ideal articulation is this: when you play a passage, aim to connect it into a musical idea, not separate notes, but really a passage which lead somewhere. Most of the time, it leads to cadence. So you can find the closest cadence and as you play the passage, your mind should concentrate on that cadence and don't allow you to make any stops in the flow before it. The third way is this: think about the pulse and the beats in the measure. Make stronger beats longer and weaker beats - shorter. The side effect of this method would be gentle accents on most important beats and they actually will sound louder. If you apply the above 3 tips in your practice, not only your articulation will be much more Cantabile, but also there would be a flow of music in your performance. It wouldn't be boring to listen to. This kind of playing would fix the attention of your listeners to your performance (provided if you use the Ordinary Touch in all the voices). |

DON'T MISS A THING! FREE UPDATES BY EMAIL.Thank you!You have successfully joined our subscriber list.  Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas

Authors

Drs. Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene Organists of Vilnius University , creators of Secrets of Organ Playing. Our Hauptwerk Setup:

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

This site participates in the Amazon, Thomann and other affiliate programs, the proceeds of which keep it free for anyone to read.

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed