|

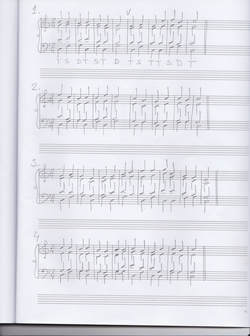

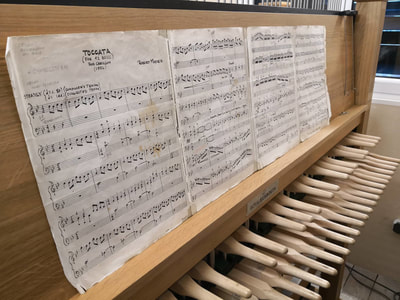

Last week I witnessed an extraordinary carillon recital by Dr. Mark Konewko here in Vilnius. It was part of the Music Composition conference at the Lithuanian Academy of Music and Theater where he also presented about the aspects of synesthesia in the organ music of Olivier Messiaen. Mark is not only a carillonneur but an organist and Director of University choirs at Marquette University. He came back the second time to give a presentation at the conference in Vilnius. Here's our podcast conversation about carillon from last year. This time he played his own improvisations and the music of Olivier Messiaen and John Cage among the music of other modern composers on the carillon. After Mark introduced me to the carillon, I can see why some organists fall in love with this amazing instrument and want to pursue a career in it. That's exactly what happened to Mark when he was a student. Together with me there was one person present at the carillon console. This was a student from the Academy, Joris. Mark even allowed Joris and me to press the low Bb or A# pedal (Bourdon) to announce the beginning of each of the 10 movements of the Cage cycle. After recital we become experts in Bb/A#! Below are some photos and two videos from the event. Let me know what you think.

Comments

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 334 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. And this question was sent by Jan. She is on the team who transcribes our fingering and pedaling scores. And she asked: I attended a djembe African drumming workshop at my local library. I had a great time. It was so much fun to play music as part of a group. I have a question...to remember the rhythms, would a classically trained musician automatically translate these rhythms into notation? (Sort of like visualizing a word that you are trying to spell.) I was able to play the rhythms by copying them, but I was not able to translate into notation. I hope that I will be able to teach myself to do so. The whole reason for me attempting to play the djembe is because I am so totally over not being able to keep a consistent tempo in my pipe organ playing and I thought that djembe drumming would provide a more whole body experience. V: Ausra, have you had any African drumming experiences in the past? A: No, not much of a chance to get that kind of experience living in Lithuania. V: What about in Nebraska? Didn’t you attend a workshop with me? One guest drummer from West Africa came and... maybe it was only me, who attended. A: I totally don’t remember it, so probably you were the only one who attended it. V: I remember I was also totally amazed by the rhythms, syncopations, what they do with their bodies and hands, and yes, they taught us to use that on our body using hands and feet, but we didn’t have to notate it in rhythms—in musical notation. So... A: Do you think it’s worthwhile doing? V: I don’t suppose it would hurt, of course, it wouldn’t hurt, but obviously this music isn’t created to write it down. It’s created to improvise and perform it in the practice. A: So it’s like a living tradition that is given from man to man. V: But if you want to transmit this tradition to other countries or cultures, and through the sheet of paper, that’s one of the primary ways to do that, unless somebody sees the video nowadays. Right? A: Yes, because don’t you think that if you would write down on the paper what they are doing it would rule some sort of magic. V: Obviously, it’s like taking a picture of somebody. Some African tribes believe that if you take a picture of somebody you will take his soul. A: Twice. V: So, some musicians even believe that, and don’t allow others to take their pictures, too. I know one. A: So now, I guess, lots of folk just take souls out of themselves by doing all of those selfies everyday! V: Right! That’s their belief at least. So, going back to Djembe African drumming as it relates to organ tempo-keeping, playing organ pieces and keeping a consistent tempo, that really helps I think. A: I think so, yes, and I think at least that was how I was taught when I was a child in my early age. My piano teacher would always tell me, “Oh, you know, we Norman people, we don’t have a good sense of rhythm. You need to go south in order to learn how to use the rhythm correctly, and tempo.” So I don’t know if it’s much of that or not, but when I studied in the United States, I simply was taught that you need to count, and that you need to subdivide everything that you are playing, and you need to listen to what you are doing and you will be fine. V: Could be part of the reason, and if Jan wants to not take it, she says that she can’t copy it herself, right? I suggest, for example, either record herself, do a video, or even an audio of those beats, or go online and look for a video that other people that are using drums are making, and slow it down by about 50%. You could adjust the speed, you know? And then if this tempo is slow enough, you could actually start to notate it. It’s like Jan is transcribing our fingering and pedaling from slow motion videos. I’m playing those pieces in a slow practice tempo, but I hope people who transcribe on our team, they slow it down even more—like 50% more, so it’s like 4 times slower than normal concert tempo, so note-by-note, basically, much easier this way. A: Well, and I think if you would transcribe it, do you think it would look something similar to what we are using in our Western music? V: Sure. It’s not modal music, it’s not those ancient exotic traditions that have more than 12 notes per octave, it’s just rhythms, syncopations, that are difficult to Jan. But, if it’s slow enough, and if she could notate it, it would look like crazy rhythms, but we could understand it, right? Especially in slow tempo. A: Yes, that’s why I think that learning rhythm right from the early age is so important. That’s why, for example, in our school, the young kids they have in the Solfège to write down also rhythm dictations not only the musical dictations. V: Did you like it? A: Well, no! I didn’t like it, because it was hard for me. V: I preferred melodic dictations. A: Me, too! V: I even melodic dictations to harmony exercises. A: Well, that’s because you have perfect pitch! V: I remember that day, the choir director of the second graders in our school tested my pitch, my ear, and she played a few notes in the middle, a few notes really high, a few notes really low, and said, “You have perfect pitch.” A: Did you know what perfect is at that time? V: No. But, I felt like...upgraded into the next level. A: That’s funny. V: Yeah, very proud. Looked down on everybody for a few weeks, and wouldn’t say, “hello” to anybody for a few months. A: Really? V: Yes. Even now, I am like this. A: No! He’s just joking. He’s very friendly. V: Thank you guys, this is an interesting question. I wish we had more experience with African drumming. We have one percussionist, who obviously knows a lot about it. Thomas, right? He can play all kinds of percussion instruments, and he was our colleague in the Academy of Music in Vilnius, and sometimes we are playing with him with organ and percussion. A: Yes, we played some duets. I, for example did some sonatas by J. S. Bach. Actually, I played it on the organ, and he played it on marimba, and it sounded wonderful! And also we did that big piece of Petr Eben, Landscape of Patmos, for many different percussion instruments and organ. V: Mhm, it had an entire set, and you performed in the Philharmonic Hall in Vilnius! A: Yes. V: With the big organ. A: It was hard for me. I don’t think it was so hard for him, because he’s an excellent musician. V: Did you enjoy this piece? Eben’s Landscapes of Patmos? A: Yes, I enjoyed it very much. V: It’s very colorful when you play it with marimba and other percussion instruments and organ. A: True. V: Okay guys, this was Vidas. A: And Ausra! V: Please keep sending us your questions, we love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice, A: Miracles happen.

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 333, of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Lukasz. And he starts with his questions, with a quote from our previous podcast conversation about performing the Dorian Toccata by Bach, where Ausra, says: ..."A: Well, unless you would use the 5th and 4th finger to make the trill. V: “Oh, that’s...that’s torture!” A: “It is! Or maybe you could play those 16th notes with your left hand"… So Lukasz later writes: I think it is not a torture, it is a necessity for Bach. Try to play Goldberg's without 5th and 4th trills in right ... and left hand... agree, at start it is difficult, but for Bach - in my opinion - necessary, same like playing parallel sixths legato in one hand - same right and left hand. I also considered these things as too difficult, something just from art of circus and not really needed for organ. Until the time I've start to work with Goldberg's variations—which I loved and when I started to play it I went crazy about it. But by the way, it completely overturned my manual technique. More—I practiced it on SINGLE!!! manual organ!!! Yes—I have been working on them for a long time, I will say honestly, I will work on them until the end of my life. (By the way, many musicians - including Glenn Gould - say and I confirm it—that as you start to play Goldberg Variations—it will stay with you for the rest of your life.) This is really amazing music—not just for listening—but especially for playing. It changes a lot—also playing the ornaments and long trills by 4 and 5 fingers appears to be not a torture :) Have a nice weekend Lukasz A: You know what I suggest to Lukasz to do? To come to St. John’s church in Vilnius and try to play a trill with 5th and 4th finger and I am probably sure that he would just break his two fingers, and he could not perform at all. And another thought that I thought about while reading his question was that Goldberg variations really doesn’t work for organ. Definitely it’s a piece that should be played on the harpsichord, and I’m positive about it. V: Right. A: So, and another thing, Glen Gould of course that wonderful performance of Glen Gould and all his Bach performance, but I don’t like his Bach’s recordings so well. So, that’s a matter of taste. And now I let you to talk about what you think about it. V: Uh-huh. I would recommend, when you say for Lukasz to come to our church to play, but not only to play in general, but to play the trill between E and F in the first manual. A: (Laughs). Then you really would die. V: Between the 4th and the 5th finger. A: You would break them—that’s for sure. V: Right. That’s question. Because those two keys are stuck a little bit inside of the action, and I cannot reach it. I have to get some big, professional help, and I haven’t gotten it yet. So, those two keys are more difficult to depress than others, and other keys are not easy to depress also, So… A: True. V: So in general, it’s really difficult instrument. A: Well for example, if you are playing Goldberg’s variation, that actually I had played this piece while working on my doctorate at Lincoln, because I was taking harpsichord all the years that I studyed in the United States. So, yes. On the harpsichord, to play trills with the 4th and 5th finger is very easy… V: Mmm-mmm. A: ...and really comfortable. So, it depends on which keys you are playing on. V: It’s comfortable to play on the third manual of St. John’s church too. A: Yes. V: It’s easy enough. Mmm-hmm. So maybe things can get adjusted because we have three manuals and in Goldberg’s variations, he usually needs two. And not in all the variations. So you can jump from manual to manual sometimes, and play on two manuals. A: But I would really leave this piece for the harpsichord because it doesn’t have the pedal. And to play such a massive piece, really, is one of the most powerful piece that is written by J. S. Bach, and to play it on the organ and not use pedal, it just doesn’t seem worthwhile. V: What about The Art of Fugue? It’s also seem to playable on the harpsichord and we heard it played by Peter Dixon. And it could be played with the pedal on the organ too. A: Well, that’s another story. I like it both ways. V: Mmm-hmm. A: That fugue. That same thing—it works well on both instruments, but not Goldberg’s variations. V: Mmm-hmm. And Glen Gould seems to… A: He did it on the piano. V: ...on the piano, with one manual. Or are there any two manual pianos around? A: I don’t know about all kinds of experimental instruments. V: I’m quite sure that somewhere there would be even three manuals. A: Sure you could find anywhere, nowadays, yes. V: Yes. But, and I remembered to an instrument museum in Vermillion and we saw some strange keyboard layout, with eighteen keys per octave or something, and it’s very strange… A: True. V: ...disposition. A: More like experimental keyboards. V: You need to spend like three years while learning to play such an instrument and then you will have a hard time playing the normal instrument. A: That’s right. V: Right? So, do you think that strong 4th and 5th finger is a good help for an organist? A: Yes, it is. V: Mmm-hmm. A: Definitely, it is. V: Mmm-hmm. Our conversation is not to prove that we don’t consider it’s importance for organists, right? Definitely try to strengthen your little finger and the fourth finger, on both hands, also. A: Yes. V: Mmm-hmm. A: For me, it’s just amazing that somebody just picks up on one line and tries to make the whole story out of it. V: Mmm-hmm. A: Taking it out of the context, from the context. V: Maybe because that resonated to him a lot, because he… You know this, when you listen to some conversation or read an article, and suddenly a paragraph or two lines stick to you because you have personal experience about that line, so that’s what happened I think. A: True. V: Good! And then, what kind of exercises could you suggest, Ausra, to strengthen 4th and 5th finger? Or are there any in your baggage of tricks, that you use everyday, before breakfast? A: Well, (laughs) you know, you got me. Do you have any special exercises? V: For a 4th and the 5th finger? A: Yes. I think actually that... V: Sure. Hanon A: Hanon, yes. V: The, even the first part, which is relatively easy, works on those two fingers also sometimes. Because, unless you strengthen those fingers, you cannot proceed to the second part. And unless those strengthen those fingers even more, you cannot proceed to the third part. So I guess for people who are interested in strengthening all fingers, and especially those weak fingers, could take a look at all three parts of Hanon, Pianist Virtuoso. A: Yes, and now I thought that I will definitely draw a comics about this thing—playing trills with the 4th and 5th finger. V: Interesting. A: And since my main hero of the comic is a pig (laughs), which surely has what? V: Two. A: Two. V: Fingers. Long and short, or short and long. A: So, it will be fun. V: Mmm-hmm. And the second hero character is what? Hedgehog! A: That’s right. V: How many fingers does he have? A: I don’t know, maybe four. V: When I draw Spikey the hedgehog, I don’t draw fingers at all, just little paws. So it wold be like... A: So you can play it still with both paws… V: Uh-huh. A: Simultaneously. V: Mmm-hmm. Yeah. We will definitely post some visual material for you too. Because some of those comics are quite funny, we hear from our readers, from other blogs that we write. But not for organists. Sometimes you might get amused also. A: True. True. V: Alright, guys. Thank you so much for staying with us through those difficult, sometimes, conversations. And we hope you get things that are useful to you. Obviously Lukasz got interesting things from the previous conversation when he was quoting us. And that resonated with him and he produced a nice question. So please keep sending us your thoughtful questions. And we love helping you grow. This was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: And remember, when you practice... A: Miracles happen!

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 332 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Steven and he writes: “Good morning Vidas, Hope all is well with you. Thank you very much for your helpful podcasts. Today and tonight I accompanied several choral numbers and performed a few hymns and Campra's Rigaudon at a very large venue out of town on a very large pipe organ. I'm nearly 70 years old, my memory isn't all that bad any more but it's not quite as quick to store information as it used to be. When I perform at the organ I'm finding it necessary to sight read a good deal more than I used to. I was familiar with the music and the instrument but hadn't performed it there in about 15 years and was given only about a month's notice to get things prepared. The instrument is fully playable with electropneumatic action but has a few quirks -- most noticeably a very deep key fall with stiff action on the pedal keys and very weak manual key springs to where the slightest touch makes an electrical contact to pull pallets. This can cause a lot of strange notes to enter when they shouldn't and leads to a lot of mistakes when playing the pedals. It's like your hands are playing on a soap bubble and your feet are playing in mud. I practiced the music beforehand every day for two weeks, 3 hours a day, to the point where my bottom was even sore to sit on the bench. Last night, due to the excitement, I was unable to get a restful night's sleep and kept waking up every hour, knowing I had to get up very early this morning and leave in the dark to get there on time. I believe I practiced too hard for too long, as I know my playing is much better than what my listeners heard today and tonight, and, to be perfectly honest, I was disappointed with myself. Worst I've ever done. By the time I finished tonight it felt like my mind was brain dead, rebelling against details, and I felt exhausted. Practice is necessary and good, but too much of a good thing can also not be so good. Or so it seemed to me, today. On the way home it occurred to me that this could be something you and Ausra might address in a possible podcast, as many times we don't practice enough. But we can also overdo it the other way, too. By the time I played the closing hymn tonight I was too spent and worn out to even sight read the notes any more and made many, many mistakes. I played this same hymn hundreds, maybe thousands, of times before and knew it forwards and backwards. But my mind just wasn't working. This is not at all like me. I'm thinking a good night's sleep the night before and more moderate practice habits are in store for me, and perhaps some advice about how to arrive at a balance at this would be helpful to others too. We know we can try too little and practice too little. We can also try too hard, which can hold us back. Maybe also, we can practice too much. We can get too little rest. A sleep aid might help some of us, but, then again, something like that could make some of us sleep through the alarm clock and wake up too late to get there on time. If you could shed some light on how to get in the middle of the road with this, I believe it would be very helpful to others as well as myself. It's hard not to get discouraged when things like this happen to us. Many thanks, Steve” V: Wow, this is a long story Ausra. A: It is. V: Have you fallen asleep while I was reading? A: No, it was very interesting. V: Good. It was interesting to me too because we all have those experiences when we practice too little and when we practice too much. A: So I would say the middle way would be the best like moderation in everything that we do but unfortunately that not always is the case. V: Do you think people usually or most of the time practice too little or too much? A: Usually too little but for example it is better for me when my pieces are not quite ready when I perform them and that way I stay more focused because if I am over-prepared then I’m sort of calmer and can’t focus so much. V: Less alert. A: Yes. V: You are playing like for yourself and not like in public then. A: True. V: Which might sound a good thing but it isn’t. A: That’s right. V: Or it might be a good thing but it necessarily is in your case. A: Yes, so now it’s sort of strange that Steve was afraid of over-sleeping because usually if you play concerts they are in the evenings, most of them, or late at night and that’s a problem for me because I’m not a night person. I’m more a morning person and for me it would be much easier to get up early in the morning and to play a recital earlier or during the first half of the day. But when I have to play recital at 7:00 or 7:30 or even later at night it’s hard for me because I cannot be in good shape so late at night because I never take a nap for example. I can’t take a nap so it’s really difficult. What about you? V: As I understand Steve was waking up due to the excitement last night and unable to get good sleep and waking up every hour, right, because of the excitement. Maybe he was nervous, it felt like things might not go well and he was stressed out. Maybe that’s why he couldn’t fall asleep and stay asleep. With me, usually when I play the night before is OK, the week before is OK, and at this point even the day of the recital is OK. I no longer feel that my fears are helpful so I kind of don’t pay attention to my fears. I do feel approaching due date. Even when we are recording this, this is Wednesday and my own recital is coming up on Saturday. I’ll be playing organ works by Teisutis Makačinas, a living Lithuanian composer who is celebrating 80 years anniversary this year. He was Ausras’ and my harmony and polyphony teacher. A: Professor. V: Professor, right. He will be there too and I will be playing three of his large scale organ works but I do everything I can do during this week to prepare myself, to practice better and to be ready but I know that being afraid of this upcoming recital and thinking about it during the night doesn’t lead me anywhere, right? So then I kind of disconnect a little bit from that feeling. Maybe that’s because I have been playing recitals for more than 25 years. A: Well the more you play, the more often you perform in public the easier it gets for you to do it because if you are performing each week then you could not allow yourself to not sleep a night before recital. You would get too many restless nights and you would ruin your health. So if you have trouble sleeping before recital I would suggest either herbal teas and if that doesn’t help there are probably pills. Consult your physician. V: Umm-hmm. So Steve also needs to perform more I guess in order not to have a big deal out of this. A: Yes, because it seems like it was very big deal for him and that’s where all that excitement came from. V: Yes. He wrote that he accompanied several choral numbers and performed a few hymns, and Campra’s Rigaudon. So one solo piece, right, was kind of this Rigaudon, and then he performed a few hymns which is also not solo music, it’s just congregational accompaniment, and then choral accompaniment of several numbers. So it wasn’t even a solo recital that he did. Obviously he needs to perform much more and much more intricate music and more often and on different organs that he wouldn’t get too stressed out about each and every recital or performance. That would be my best advice for him and others. A: And for me I got the impression that Steve a little bit blamed the instrument that he was playing on. V: Umm-hmm. A: I like his comparisons about feeling that he plays pedals in the mud. I think that’s so human-like that anything got wrong or not as well as we expected that we are trying to find something to put blame on and for organists it’s usually the instrument. Do you think it’s fair? V: To blame others? A: To blame the instrument. V: Or the instrument. Sometimes we blame other people. A: Yes. V: Or the audience, or choir members, or people who make noise, or construction workers on the street, or anybody else but myself. So yes, imagine a situation if Steve could have played well on this instrument without major mistakes and he was happy then his letter might have sounded much different to us than from what he wrote. Maybe the action of the instrument wouldn’t be a problem then. A: Yes, and for me I got the impression that it was not a problem because he worked too much on these pieces before this recital. I think it was the main problem that he actually could not rest the night before. V: Umm-hmm. A: And that’s why it was hard for him to go through that recital without many mistakes and as he wrote that in the last hymn he couldn’t sight-read through, he made too many mistakes. I guess he just didn’t have enough energy left and that’s because of that restless night. V: Sometimes we make mistakes, sometimes we don’t make mistakes, sometimes we get good sleep, sometimes we don’t, right? Things happen that we can’t control and even it’s not up to us sometimes, right? And we still have to get up and go to the organ bench and play to the best of our ability, right? That’s what we do as professionals and have you ever played Ausra, recital while being sick or feeling sick. A: Oh yes, not once. V: Not once, me too. A: And without sleeping much the night before. V: How did it go? A: Well surprisingly enough those recitals went even better for me than like regular recitals. Because again when I didn’t feel well, when I would be very tired I would have to concentrate more. V: Umm-hmm. A: Otherwise I would just know that I would collapse on the organ. V: But again, this is your experience of playing more than 25 years in public. Maybe somebody like Steve while being sick and without rest couldn’t perform at all. Maybe he would be tempted to cancel his performance at the last minute. A: Well sometimes I think it’s better to cancel your recital than to do a sloppy job. Don’t you think so? V: But you don’t know if will do a sloppy job beforehand or not. A: You never know but if you are really sick. V: It depends, right? If you have a fever and can barely walk out of bed then maybe it’s better to cancel, right? But I also played recitals while having high temperature and as you say it went surprisingly well. A: But you took a big risk, not because I actually didn’t care about that recital at all, I just cared about your health. V: Umm-hmm. A: Because playing with high fever you might really damage your heart and might not be able to perform at all after that. V: You know I knew that before and for that particular recital, this was improvisation recital… A: No, it wasn’t improvisation recital, it was a Christmas recital. You played Christmas repertoire. V: Oh, I played more than one while being sick then. A: This was with a high fever that you had. V: So then I think I played without too much tension from myself, conscious effort. I thought I would play just like for myself or for you, not for others and that helped me relax and somehow overcome this, right? OK so sleep well, get some rest, get good rest before recital and perform more in public, more often, with different programs, and gradually more difficult programs too, more solo pieces. Thank you guys, this was very interesting to discuss. Please keep sending us your questions, we love helping you grow. And remember when you practice… A: Miracles happen. SOPP331: Could you please take a look at my suggestions for progression in C major and a minor11/15/2018

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas. Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 331 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Lev, and he writes: Hello Vidas, Could you please (if you find time) take a look at my suggestions for progression T1TS2SD3DT4T in C major and a minor (Exercise 9-2 from Harmony for organists course) and give me short feedback about mistakes. I'd like to make sure I've understood the harmony stuff correctly so far. Thanks in advance and best regards

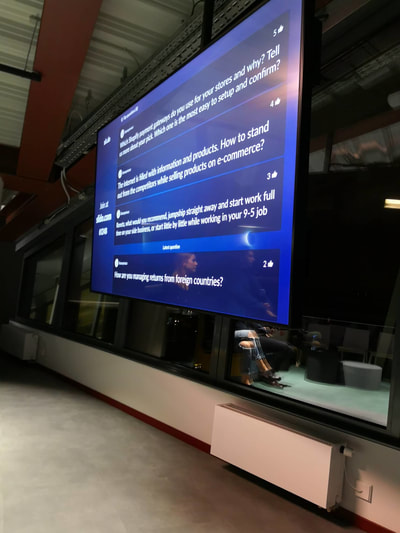

V: Ausra and I just a moment ago looked at this file, and we were actually very impressed. Right? Because we didn’t see almost any mistakes. A: Yes! We could not find any, except from orthography. When you put slurs in the Tenor voice, they need to look up. V: If the stem goes up, then the slur or the tie has to go from above, too. If the stem goes downward, faces downward, like in the alto voice or in the base voice, then the note slur also needs to go from below. Right? A: Otherwise, all the voice leading is correct. V: This is really nice. The assignment was to harmonize, in four parts, a progression of three chords, basically: Tonic, Subdominant, Dominant, and again, Tonic. But, make the Tonic sound twice, the Subdominant sound twice, the Dominant sound twice, and the Tonic again sound twice, but not repeated, but in different melodic positions. So, that’s what we were talking about in the harmony course, so far, and Lev seems to understand the subject very well. A: Yes, that looks like that. V: Do you have these exercises in your harmony class, Ausra? Similar ones? A: Yes, I have this exercise. I believe it’s taken from my course that I’m teaching. V: You mean stolen! A: Yes. Never mind that, it’s general knowledge. It’s actually suited for beginners. V: Once people know how to put one chord correctly, how to connect two chords correctly, and then how to repeat the same chord in a different melodic position, then they could make a longer phrase out of four or six or seven or even eight, chords, and starting from different melodic positions. For example, in C major, you could start from the note “C” in the soprano, “E” in the soprano, or “G” in the soprano! And, you could also do closed position chords or open position chords. So, in C major, there could be, like, six versions. Right? A: That’s right. V: And then the same thing in A minor, also, one third below. What about your students, Ausra, at school? Do they make mistakes on this kind of exercise? A: Well, some do and some do not. So, it’s different. V: Of those who do make mistakes, what would they lack? What kind of knowledge do they lack, or skills? A: I think they are probably too lazy, some of them. Some of them don’t want to apply the rules, and that’s a problem. V: Don’t want to follow the rules. A: Yes. V: They are artists, right? A: Well… V: Like myself. A: They imagine themselves, that they are artists. V: I also don’t follow the rules. A: I wouldn’t call them artists. V: Would you call me an artist? A: Yes, but you know how to do these exercises, so don’t compare yourself with my students. V: Right. A: Who are like 16, 17, 18 years old. V: Do you remember my harmony exercises from school like 20 or 30 years ago? A: Yes, I do remember. V: I did show them to you, right? A: Yes. V: What did you think about them? A: I thought that you are better at writing musical dictations than harmonizing. V: Oh, so I have better musical pitch than head… A: that’s right, that’s what I thought… V: Than brain… What about yours? Do you remember what your experience was when you were in school? A: Well, let’s face it, you know, I finished the school which is much better than yours. So… the requirements in our school were much higher than yours? V: Why would you say that? A: Well, because it is true? V: Is it? Are you sure? A: Yes, I am definitely sure! V: Take it back! A: No, I will not! V: Okay, I feel so sad, I think I’m going to cry, but maybe I will continue teaching people today, too. I’ll cry after the podcast. Okay? Remind me to cry. A: Okay, I will! V: So, Lev is doing a great job, I think, with harmony. I wonder if he plays them—if after he writes them he plays them, because it’s really beneficial, right? A: Yes, it is! Sometimes I think that we spend too much time on writing down things, and not enough of practicing them on the keyboard. V: Because, the main skill that we are trying to develop is practical, not theoretical knowledge. A: True. So, you need, of course, to do written exercise, because if you start right away doing them on keyboard, it might be too hard, and then you might make voice-leading mistakes, and do a sloppy job. But after writing them down for a while, you really need to go and practice them on the keyboard in various keys—not only in C major and A minor. V: Right. The exercise for hymn in Harmony for Organists, Level 1 was in C major and A minor, because just in that week we have those pairs of keys. In school, Ausra, do you also assign paired tonalities? A: Usually, yes. V: Because it would be too much to do everything. A: That’s right. V: Only crazy people could practice everything. A: But, for example, this kind of exercise, I don’t give them to do it as a written assignment. I give it to my students to play it on piano from any position in a given key, and then they have also to sing it, too. V: Oh, that’s a different subject. A: Yes. V: In which class do they have to sing it? A: In Solfeggio. V: Ear training? A: Yes, ear training. I think Solfeggio is a term which even Americans should know. It’s sort of international. V: So, Solfeggio with two Gs. A: Yes, it comes from the French. V: Or Italian. A: I think from the French. We might check on it… V: Solfège… right…. A: Solfeggio. V: If “Solfeggio,” then it’s Italian, if “Solfège, then it’s French. A: Yes. Because, ear training is not…. well… not a term that I really like, because it doesn’t describe so well what we are doing in the class, because ear training courses, as you call it, in our school….. first comes the ability to sight read things—to sing things from the score. That’s why we call it Solfège. V: Because we use syllables: Do-Re-Mi-Fa-Sol-La-Si A: Yes, that’s right. And of course, we do other stuff as well, so.. I prefer the “Solfège,” not “Ear Training” term. V: Right, that’s kind of International. In talking about A minor, or any minor keys, what are some challenges that people should overcome when harmonizing these progressions? A: Well, of course if you are in a minor key, you need to raise the seventh scale degree, then harmonize the dominant chord. V: Why? A: Because Dominant is major in both major and minor keys. V: Why? Always ask this question, Ausra, and then you get to the bottom of things. A: Why? That’s tradition that you need to carry on. V: Maybe it’s a stupid tradition, you know? Somebody started it, and we are living in the 21st century, and this tradition came from the 17th century. Why should we follow the 6 or 5 centuries tradition. Maybe we should do whatever we want! A: Yes, you can do that. I don’t mind. V: Would it sound good? A: No. V: Why? A: Well, because then you could not resolve it to tonic? V: Why do we have to resolve everything to tonic? A: That’s how music works. You have consonants, and you have dissonances, and you are building tension and releasing it… V: What if I don’t want to release tension? A: Well… V: Or Build tension? A: Well, if you compose music without releasing tension, I think your listeners will run out of the church after hearing you for 10 minutes, probably. V: Maybe that would be a good thing. They would run and get exercise. A: It depends upon what your goal is! V: Getting people into fresh air. A: True. V: What about if I don’t want to build up tension, and just want to play things calmly—so without seventh scale degree raised? A: Well, you could do that, but then you wouldn’t get a dominant chord. You could not call this chord in A minor key, E-G-B. Yes? If you wouldn’t have a G#, you could not call it a dominant chord. Then it would have another function. It would be more like a subdominant chord. So, that’s another story. V: Wow. But then, people would not run out of the church. A: But maybe they fall asleep. V: Oh! Sleep is also good. A: True. V: We get more refreshed after sleep, too. Okay guys! This conversation is going to the silly direction now, and I hope you got some entertainment, so please keep sending your questions to us. We love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice, A: Miracles happen. Yesterday I was invited to participate in the panel discussion at Oberlo Vilnius headquarters for Shopify Merchants Meetup during Global Entrepreneurship Week where I talked about my experiences of running our Secrets of Organ Playing blog, podcast and store for the motivated group of young Lithuanian entrepreneurs.

Thanks so much for Oberlo team who put it together: Giedre Sarapinaite, Sandra Saukaite, Donatas Pranckenas and probably others whose names are a mystery to me. Also thanks to Roneta Bajorinaite and Matas Pajarskas who were the panelists with me. All you guys are so inspiring! It was exciting to look back at those 7 years since I wrote the first post on this blog. We were asked the following questions (among many others) by Giedre and Donatas who moderated the discussion: How did you start? What keeps you going? What are the good/bad/ugly sides of running your business? How did you get your first sale? What are the best 3 self care tips you have? How did your team grow? After the event everybody was very excited and was happy with how each of the 3 panelists shared their highs and lows, struggles and victories without artificial facade that we might see in many events of this kind. I know I was inspired to choose myself when I came to Entrepreneurship Week event at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln back in 2006. Fast forward 12 years and we come full circle. Now it's my turn to inspire somebody else to do the same in their own niche. It was funny because normally people who started their businesses first got their business degrees in college and I had to learn everything from scratch by doing, by making mistakes, by educating myself. After the meetup a lady from the Vilnius Rotary club came up to me and said they would be delighted to listen to my talk at their meeting so we'll see where this entire thing leads. I think a lot of people in attendance are looking forward to more of these meetups in Vilnius. Maybe Oberlo can lead the way as they already are doing. Thanks for sticking with Ausra and me all these years! We appreciate it more than you can imagine. And we hope to continue helping you grow everyday as many of your love letters we receive continue to demonstrate. Because of this the list of questions for the podcast is getting longer and longer so we appreciate your patience while you wait for your question to be answered. But we'll get to for sure... Below I'd like to share some of the photos we made at the meetup (the last two are by the people from Oberlo). Let me know what you think.

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 328, of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by David. And he writes: Hello Vidas and Ausra, This past Sunday I completed the 40-week course. I really liked the course and thank you for it. As requested here are my comments. Yes I can sight read better but still need more work. I tried several new pieces I had tried before the course and I was better. I was away for 2 weeks in the summer and caught up by doing 2 days in 1. Not a good idea so I am repeating from week 29 on. Some comments:

Best regards, David V: Oh this is nice that somebody has completed our Organ Sight Reading Master Course. A: Yes. That’s very nice. V: And, this feedback tells me also some things that are working and some things that could be improved. And, obviously, we need more feedback from other people. A: Sure. V: For example, David writes that for a number of weeks he’s trying to do two weeks in a row, in one week, which is probably too much material. A: Yes it is, because you always need time to get through things, to, sort of to grasp them, to observe them. V: Mmm-hmm. A: And if you will do too much at once, it will not work. V: It’s like with eating fish oil pills in the morning, right? It’s very healthy if you have just one. A: True. Because you cannot skip the next day and take two pills in one. V: You gave me one pill today. A: Yes. I gave you one pill. V: And what would happen if I had two pills? A: Nothing. V: Nothing? A: I think that your body would not absorb all the things from it, if you take too much, at once. V: I see. A: Or you would get poisoned. Maybe not from fish oil but from other pills. V: Will I become more like a fish? A: I don’t know. We will see. V: With quills and things like that. A: Scales? V: Yeah, scales. Can I breathe under water then? A: I don’t know. V: Maybe I can swim faster. So guys the same is with organ related activities. If you skip two days, just I think it’s better to continue in a normal pace, afterwards. A: True. That’s true. V: If you skip more than a week or two, and you feel that your fingers and feet are weaker, and the skill is decreasing, it’s another story Ausra, right? A: True. Because aside practice for example, I see that it’s beneficial early if I’m practicing, let’s say in the morning, and then later in the evening, when I do very big breaks. Then maybe this, my practicing counts for two days. But otherwise, no. If, let’s say I sit Sunday on the organ bench and do all my practice at once, for two days, it doesn’t work. V: Mmm-hmm. You still need to have regular breaks. A: True. V: And if a person skips a few weeks in a row, and then comes back to the organ bench, obviously, the skill is not there anymore. And I think it would be wiser to pick up with a slower pace first, to adjust maybe a week or two, to get used to the new routine and take it easy at first. A: Yes. That’s right. V: It’s like, I was doing those pull-ups in the summer. I was progressing day after day, week after week. And then I got, I think, some sort of stomach flu or something, and I didn’t do my pull-ups for a week or more, even. And it would be stupid for me to try to attempt to do the total number of pull-ups I was able to do before break. Right? A: That’s right, yes. V: Alright. David, Ausra, also writes, that it was probably too easy for him until week 29. So that’s the thing that is so individual for each person, right? A: Yes, it is. V: We have various skill levels students here in our courses. And for somebody is really difficult to play, too difficult to attempt even. A: That’s right. And in general, people are quite poor sight-readers. V: Mmm-hmm. A: I notice that on my students. And I thought that after we harmonize an exercise, usually it’s eight measures long, like a hymn… V: Mmm-hmm. A: And I invite them to play what we harmonized. And it’s very hard for some of them to do it. V: Mmm-hmm. A: And sometimes we get so sloppy that after a while I simply stop doing this experiment with them and start asking them to play it. V: Mmm-hmm. A: And it really surprised me because usually when we start harmony we are at the tenth grade, or eleventh or twelfth grade. That’s when we teach them harmony, basically in the high school. And we start to study music at the age of six or seven. Some even at the age of five. So let’s say, at that age, after ten years of studying music, they are still not able to sight read easily what we already harmonized on the paper. V: They don’t have any musical intuition. A: I know. V: Mmm-hmm. A: That’s just too bad. Not all of them, but actually most, most of them. V: Most of them shouldn’t even study music, I think. A: Could be. V: Do you think, what’s the percentage of them that will become musicians, professional musicians? A: Well, I think many of them will become professional musicians, but that’s a question if they will be good or not, and what they will achieve. V: Mmm-hmm. A: I think ten percent of them will achieve what we want and they will be really great. And I think that ten percentage that also will become musicians that will be either mediocre or always will struggle for bread and butter. V: Right. If a person applies to the orchestra, let’s say, spot, and the one who can sight-read better will always win the spot, over the next person who cannot. A: Sure. V: Of course sight-reading on the violin is a different thing than sight-reading on the piano. A: Yes because you have only one line, so. But still I believe that every musician has to read on the keyboard. V: Mmm-hmm. A: Because they all study keyboards, since very early age. V: And it does give you some perspective about the harmonies, about musical composition, about how the piece is put together. If you know this harmony structure, if you are feeling with both of your hands, the key changes, and even for solo instrument players, is useful. A: True. Otherwise if you will be thinking all about your melodies and nothing will work. V: Mmm-hmm. What happens sometimes most of the semester they would practice alone, and at the end of the semester, accompanist would come in to the practice room and they together start to rehearse. And this new part suddenly makes no sense to the soloist. I think a good soloist will always need to get acquainted with himself or herself with the full musical material. A: That’s right. V: So, that’s why we, that’s why I didn’t rush introducing three steps or even two steps, because it was very methodological. I first went through separate lines until the very end, and then came back with two voice combinations, which is of course a challenge sometimes for a lot of people. It’s much harder than one line. A: Oh yes. True. V: And another comment that David has here, that most of the early weeks were in d minor, and only later, the course was transposed into various minor keys. The reason I decided to put off transposition to the later part of the course was that students should familiarize with the texture first. Because Bach’s art of fugue is not a beginners texture at all. It’s completely advanced fugal texture. And first you practice in one voice, then in two parts, and three parts, and if I added to this challenge, transposition on top of that right from the start, I think for a lot of people it would be impossible. Even as it is it is difficult course. So it’s good that David found first weeks too easy. Maybe he could skip some material. Maybe just play faster or something. Still he should find it useful. And his own level will then start to be revealed in the middle. A: True. V: Right? A: Yes. V: Would you agree, Ausra? A: Yes, I agree. V: Would you start transposition right from the start? A: Probably not. Well, I would do, but if you are beginner, then not. V: Mmm-hmm. And if he needed more keys, of course it’s wise to supplement study material with other pieces. And he’s writing that he’s studying Dupre's 79 chorales, which are in various keys. A: Good. V: But here is the thing; he’s using baroque pedaling. I don’t think Dupre understood anything about baroque pedaling. A: True. I wouldn’t do a baroque pedaling in Dupre’s chorales. V: Dupre always emphasized legato playing, and even in his edition for the Bach organ works, he always used finger substation and glissandos, and heel-toe pedaling, just like he would apply it in his own works, or 20th century works or 19th French organ works. So when somebody is playing 79 chorales by Dupre, please use modern fingering and pedaling. A: Yes, I think it would work better. V: Mmm-hmm. Excellent question I think, and feedback. This is really helpful. Thank you guys for doing that. And please keep sending us your questions. We love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice... A: Miracles happen! SOPP329: I am having pain in my inside right groin from trying to hold my knees and feet together11/12/2018

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 329 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Hanna and she writes: “Hi Vidas, I am having pain in my inside right groin from trying to hold my knees and feet together. It was all I could do to do 10 reps of the Master organ course Week 2 Day 1 this morning. I am only 5' 1" and it is difficult for me to perch on the edge of the organ seat to reach the pedals as you describe. I can only hope that the pain will decrease with time. I was not able to do all of Week One in the Pedal Virtuoso course last week, but am trying to be more faithful daily this week. But things are improving, more accuracy bit by bit. –Hanna” V: So Ausra, what do you imagine is happening? A: Well I think probably Hanna is working too hard. V: If something is hurting then you are not doing it right, right? A: Well, yes. I would like to talk a little bit about that thing of keeping knees and feet together. I never did it for myself. It never worked for me. I learned about this kind of thing late in my life when I was already completely shaped as an organist. I never really learned to do that but it doesn’t hurt me for not doing it. And I’m playing all kind of repertoire from renaissance to modern and I can do it perfectly without keeping my knees and feet together because as Hanna me too, I’m not very high and really I don’t have long legs, I don’t reach things easily on the pedalboard so I have to find my own ways to do things and I think each of us is very unique and what works for one person cannot work for another person. So always when you have rules you need to take only what really works for your body and not try to hurt yourself. V: You’re right Ausra. The idea of keeping the heels and knees together is simply to move both feet as a unit. Not two separate legs but one and for some people it’s harder to do than for others because of body type and physique and obviously if your playing in the far reaches of the pedalboard it’s crazy to do this. I have to emphasize this, never try to hurt yourself because it’s painful and it will lead to injuries eventually. A: Yes and Hanna says maybe in time it will hurt less. If you won’t change something in your practice, your playing, it will hurt only more because that’s what pain does. It increases, usually, unless you change something. V: I recommend for Hanna just to play with the inside portion of the feet. This way her knees will be pointed inward, not outward, and she will be still playing correctly and without pain. A: Probably yes because I never imagined how a person with big hips can put his knees and ankles together. It’s kind of a weird feeling. V: Right. And of course this Pedal Virtuoso Master Course that she is talking about obviously is just a set of exercises of scales and arpeggios. In real music we might find a passage or two in entire composition like this. It would be completely boring to have pedal line comprised only from scales. It’s not an etude. A: So if you are working on some technical exercises like Pedal Virtuoso Course you don’t need to do only that and please don’t play entire day only on this course because you might really get injured yourself. V: Right. This course is probably good for warming up. A: Sure. Anything that you do you have to have that feeling of moderation. V: Yes. Never over-exert yourself. A: And mix that practice with some other practice, work on repertoire. V: And whatever you do, always take our advice with a grain of salt, right? Whatever I say it might work for me but you have to think about yourself too, if it does work for your body. And you might even misinterpret my words sometimes. I don’t remember writing “You have to keep knees together and feet together in extreme edges of the pedalboard” unless there is something else that I am missing from Hanna’s writing. What about Ausra if she doesn’t turn her lower body to the direction of the playing. Maybe she’s playing upper notes but her knees are facing to the left. That’s hurtful, that’s incorrect. A: I don’t know how it’s possible even to do, even to try to do. V: If you always face to the center, right, your knees are facing to the center but your feet are trying to go up, up, up, the pedalboard. A: That’s impossible to do. I can’t even imagine it. V: It’s really hurtful and dangerous. A: It hurts you from thinking about it. V: I believe people can sometimes forget to turn their lower bodies to the direction they are playing. Their knees should always point to the note that you are depressing with the pedals. Either left or right. So then maybe even Hanna can reach the high notes with both feet together and knees together. I don’t know if she tried that or not. You see how sometimes we could spot a simple solution I think too. So if Hanna is listening to this or reading our conversation it would be nice for her to try the right way, the way we advise, and report us back if that helps. A: True. In general the more I listen the more I think that not everybody needs to play everything. You need to select what you want to play and what works for you. Don’t you think so? V: I think that you need to explain it a little bit more what you mean. A: I mean that if something really doesn’t work for you, doesn’t fit your body, maybe it’s not worth trying to and hurting yourself. V: Umm-hmm. What you mean is that you can become a good organist even without playing exercises. A: I was talking also about repertoire as well. V: As well. A: For example if my hand is very small and I will pick up pieces that needs big reach then I will be doomed to hurt my hands. V: Right. Always listen to your body. And maybe sometimes a thick texture is too much for you; maybe you need to play trio sonatas. A: Yes. V: Do you like trio sonatas Ausra? A: Yes, I love them. V: For that reason. A: Yes. V: Because you have small hands. A: Well, I have moderate hands, I wouldn’t call them small. V: Can you reach an octave? A: Yes, I can do that. V: Can you reach an octave and a fifth like Liszt? A: No. (laughs.) V: I once tried and I think with my left hand I reached an octave and a fourth. That’s a perfect eleventh, an interval of eleventh but only with the left hand and with the right hand I can only reach a tenth, an octave plus a third. A: So you still have a greater reach than I do. V: Can you reach a ninth? A: Yes, yes, it’s hard but I can do it. V: (laughs.) It’s very painful for the hands but fun to stretch just to see how far it can go but never try I think some tools to stretch your hands. Never fasten your hands and fingers to some appliances like in medieval times they would torture humans. Don’t do this. This wouldn’t be nice. Excellent. We hope this was useful Ausra. Do you think it was useful? A: I hope so. V: OK A: I’m not sure but I hope so. V: Let us know if you think our suggestions to Hanna were suitable and it could be interesting to get feedback from other people who are not tall too. Alright. This was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: And remember, when you practice… A: Miracles happen.

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 327 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Timothy and he wrote: “I recently purchased your fingering for BWV 553, and I stopped dead at the transition from the first page to the second. The last right-hand note on the first page specifies finger 3, and the first note on the second page is also 3. Is that a misprint? Am I missing something important? How can the third finger jump like that in the middle of a fast 16th note passage? Timothy” V: So Ausra, here we go. Let me find the score. You don’t know exactly what he’s talking about but you can imagine. A: I can imagine that we will look at that complete spot but in general usually you use the same finger between measures when you want to articulate. V: Umm-hmm. A: And that’s a perfectly normal thing to do in baroque music. V: Even though the tempo fast, even though there is like sixteenth notes. We’re looking at this measure and it ends on the third finger and the next is also three. A: Show me the next measure. V: I don’t have the next measure but you can imagine there is G. So there is a leap upward a perfect fourth from D to G. You know why I wrote this? Because this figure at the end of the measure, F#, D, C#, and D has to be played by has to be played by 5, 3, 2, 3. This is really fitting the hand; it’s in one position, right? And the next position starts with the next measure, G, F#, G, and D. Also starting with the third finger, it’s also the next position. What you have to do is just shift the hand a little bit to the right. A: Yes, you know when a question arises like this like in Timothy’s letter I think he is probably not comprehending deeply enough what the baroque articulation is. V: Umm-hmm. A: That it’s perfectly normal because between measures you do a slight break actually. So usually the last note in each measure is a little bit shorter in order to have more space between a strong beat. V: And that’s especially true when you have to emphasize the beginning of the next section and that’s the exact case here at the end of the first page going to the next page it’s like a break between two sections. A: Yes. And I don’t know what organ Timothy is playing, if it’s mechanical or electronic organ. V: He didn’t say. A: But if he would play on mechanical organ I think he would get a better understanding of what we are talking about. V: Umm-hmm. And it doesn’t have to be in time with metronome like a robot. A: True, true. V: Because it’s changing the section, you have to even slow down a little bit like going with a car and you suddenly have a turn, what you do is slow down and then after the turn you speed up a little bit. You do it so naturally of course on the organ, not too much, not over exaggerated, but naturally with breathing, with phrasing, it’s very natural, right? A: Yes. V: So Timothy needs to understand the basics of baroque articulation and fingering too, right? A: True, and on this C Major Prelude it’s fast but its allegro, it’s not presto so you would have enough time to move your hand. V: It’s not a gigue. A: True. V: Definitely. You play the same figure with the same finger sometimes, the same intervals with the same fingers; you play with the same fingers before the strong beat sometimes in order to make a rest, right? A: Sure, and if you really don’t trust us and don’t want to play baroque music in historical style you can do your own fingering and play whatever you want even you can play legato. V: With finger substitutions too. A: Yes, it’s a free world. V: Umm-hmm. A: But definitely if you would come to a historical instrument you could not play legato. The instrument would not allow you to do that. V: There is a counter-argument to this because sometimes in Lithuania people say that “Oh when I play historical organs then I will use historical fingerings. But now I’m only playing Allen digital organ, why do I need to jump from three to three of the perfect fourth?” To this question what would you answer Ausra? A: Well you never know when opportunity might appear for you to play on historical instrument plus if you will learn it in stylistically right way right from the beginning it will be easier for you to go from one instrument to another and it will be really hard to re-learn something. I find it’s easier for me for example to learn a new piece than to correct something that I already have learned and to play differently. V: Because it’s hard to teach an old dog new tricks. A: Yes and I think it’s also because our muscles have their own memory. V: Umm-hmm. So your muscles are like dogs, old dogs, because they are trained one way and you suddenly say “No, no, no, this was wrong and now you have to learn the other way.” They’re confused. A: Yes, true, because it’s connected to your brain so it’s very hard to learn. It’s possible but you just be wasting your time. V: Life is short, right? We have to learn the pieces the most efficient way so that when opportunity arises you could play with historically informed fingering and articulation too. A: But even on the electronic organ it will sound better if you will articulate. V: Obviously, yes. Even though the keys are longer and you have to work a little bit harder. The same goes with pedaling too on the modern pedalboard, it’s not so convenient to play with historical pedaling, but… A: So you know what I wouldn’t do if I want to articulate? V: No. A: And would want just to play legato or whatever? V: Say it. A: I wouldn’t play baroque music then. V: Ahh. A: There is so much music written so play something else. V: Umm-hmm. And if your person loves baroque music? A: (laughs.) If person really loves baroque music I suggest that person wouldn’t hurt baroque music by offensive playing legato. V: If a person loves baroque music he wants to know more about it, not only play, but dig deeper and when you dig deeper you find out so many new things. A: Listen to Bach’s cantatas, there are so many wonderful recordings. V: Umm-hmm. A: Historically so nice recordings that reconstructed the playing manner of Bach’s time. Listen to them. V: Just simply observe how violinists are playing, their bowing techniques, they remind of historical articulation too. A: Flute or oboe, they articulate. V: Up and down, up and down the bow or tonguing. A: Tonguing, yes. That articulation was not just common for organ or harpsichord at that time, it was common for every instrument and everybody articulated. V: So, I guess you know that Timothy is not criticizing the choice of articulation probably here, but doesn’t seem to understand that when you play with historical fingering this articulation comes natural, you don’t have to think about it. A: True, true. That’s why it’s important how you choose fingering. V: And in that score that he has of C Major Prelude and Fugue, BWV 553, there is no articulation written, so we don’t know if he is playing with articulation or not. Maybe he is not always articulating before the strong beats, right? A: You have to do that. V: Right. A: I have two students who are really beginners at the organ and they are adults and what I’m suggesting them to do that if it’s too hard for them to articulate every note as I would like them to do, at least that they would articulate before each measure and emphasize the strong beat. V: Oh, you are so forgiving. A: And then I would insist that we would articulate each figure, each beat of the measure, and then we would try to articulate each note. V: Did you tell them that they could play the passage with one finger. A: Yes, I told them, it works actually very well and they got it. It’s very helpful. V: Just play the passage with one finger and once you achieve as legato as possible with one finger try to imitate with all the fingers and that would be ideal articulation. A: True. V: And if you use our fingerings this ideal articulation will come naturally without you even thinking about it. A: Well, but you still have to listen to what you are doing. You have to control yourself while learning. V: Right. OK, I think Timothy can try an experiment and he will find out for himself what works for him. Thank you guys, for listening, for sending us your wonderful questions, we love helping you grow. And remember when you practice… A: Miracles happen. SOPP328: A certain publishing house has expressed an interest in publishing one of my compositions11/10/2018

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 328, of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Steve from organbench.com. And he wrote: Good morning Vidas, Hope all is well with you. Most of my compositions are listed now for sale with Sheet Music Plus Press and Noteflight Marketplace. Under the terms of this arrangement I retain ownership of my compositions and copyrights and can exercise control over listed retail prices and product descriptions. Royalties are at or near half of the retail price, for every copy sold, payable every month or quarterly, by PayPal or written cheque, my choice. Their online catalogs reach 110 countries world wide. A certain publishing house has also expressed an interest in publishing one of my compositions separately, namely, the E Major Op. 17 Communion song. The standard contract from this firm arrived today in duplicate, and, if I sign it, I will be assigning ownership of this piece to this firm. In return I'm to be paid through PayPal just once a year, the standard 10 per cent of the retail cost, which is set by them, for each copy sold. I'm informed that this music will be listed in a future catalog, but due to the large number of contracts they already have, it may be several catalogs before it is published. As you probably already know, they are a much smaller music publisher with a much narrower, focused market, their catalog does not provide the composer with the control to set the retail price for his work himself, and it has no playback feature to allow customers to hear the music they're thinking of buying. Revenues are about 60 per cent higher when online catalogs have this feature. This firm also provides no means to affiliate with my web site either, to provide it with links or search boxes to allow it to help generate sales for them and thereby generate commissions for me. This contract, as worded, is one page, a mere three sentences long, between me and the firm, with no stipulation about what happens to my music or any accrued royalties in the event of my death or the closing of the firm. I may yet change my mind, but as of this moment I don't feel that signing this contract is in the best interests of my music, myself, or my legal heirs. It seems that it leaves too much unanswered, and there are other better alternatives available. Just my feeling. I'd enjoy hearing back from you. Wishing you and Ausra the Very best, Steve V: You know, this is a message that Steve wrote, and I deliberately excluded the name of this company, because Steve didn’t feel that people should really know. Because his feelings are not necessarily objective feelings. Maybe other people would want to be part of this company, catalogue. What do you think, Ausra? A: Well, nowadays, when I have a question or a doubt about something or somebody, I usually try to Google it, and to see what other people have told about the same problem or the same company or the same person. It’s really useful because nowadays it’s really hard to make something bad, or something really hurtful to somebody and don’t be punished. V: Mmm-hmm. A: Maybe you will not get legal punishment from police or whatever, but people will punish you because opinion will spread out through the internet and if you will make something really bad, people will find out about it. V: Mmm-mmm. A: And your company or something will be just doomed. V: Look how we’re buying things. For example, myself. When I buy books, I most often buy books from recommendations from other people I trust. A: Sure. V: So the same is with trusting companies, and being in relationship with them, in contract, right, like composers. To me, releasing the ownership of the work has to be done with certain consideration, right? You don’t know how successful you will be as a composer, right now if you are just starting, in the future, right? And if you are releasing your rights to them, and they owe you just ten percent per year? Ten percent! A: That seems like nothing. V: Right. A: Really. V: Paid just once per year. Imagine if you’re starting to make a living from your music, right? And you only get your salary once a year, that’s a joke. A: Yes, it is. V: You need to get it once a month, or even faster—twice a month, or even as soon as the sale is done. A: Also, what I trust when I think about making an important decision, I think about certain impression, what I got from reading a letter. V: Gut feedback. A: Yes, because... V: Gut feeling. A: Gut feeling, yes. Because that first impression is most often the rightest one—you need to trust it. And if you feel that something is fishy there, then don’t do it. V: Mmm-hmm. And Steve mentions Sheet Music Plus, at the beginning, and Noteflight Marketplace. Those are two places that he is publishing his compositions now. And it seems to me that the owners of Sheet Music Plus and Noteflight, have understood the importance of playing the fair game—being fair with your customers, with your members. Because Sheet Music Plus, gives you the opportunity to be affiliated with them. You could sell your own music on your own website, while, by having links on your website which would go to Sheet Music Plus, and banner ads and everything else that he needs, special codes, snippets of codes that they count impressions and clicks. And you would get statistics about that, and you would be paid through PayPal once a month. It’s really nice. And Noteflight probably also behaves similar way. Noteflight is a platform which allows you to produce your own sheet music scores. It’s like Sibelius, but it’s online in the cloud. You don’t need the software at all. You create your score in the browser, and if you have a premium account, for certain membership fee, yearly or monthly, you have many more benefits with them. I’m not advertising them or endorsing them, I’m just saying what they have, and Steve produces his entire organ works this way, by working on the browser. And it seems that he enjoys it. A: Yes, I think it might be… V: Suitable solution. A: Suitable, yes. V: Because Sibelius is expensive and you have to install it and if you lose your computer or break your computer, you have to reinstall it. It’s a big mess and a big hassle. A: Yes, and takes a lot of space too. V: Mmm-hmm. A: It might slow down your computer if it’s not the newest one. V: It has certain features that Noteflight lacks and special benefits, but for people who are just creating simple scores, in the browser, is just painless process I think. A: Because last year, for example, at my work, I asked for computer specially to install Sibelius, and then I had to uninstall it because my computer just slowed down so much that I could not work on it. V: Mmm-hmm. Right. Here is we’re looking at the Noteflight platform, and they Marketplace, where you could sell your own scores through them. So it seems that they found a nice business model and Sheet Music Plus, and also NoteFight completely different business model, but still working business model I think. But, Ausra, do you know what the biggest problem or challenge for Steve still is? A: I don’t know. V: You could feel it already in my question. A: Well, yes, a little bit. V: With all these tools, and all these opportunities, right, and once a month PayPal payments to your account, and everything is fair and wonderful, he even has opportunity to insert MP3 files for listening the scores before buying. Customers could listen to the score as a sample. It’s really nice. But you know, the biggest problem, Ausra, still is, what? Finding your customers! Neither of those platforms will not guarantee you, your customers. A: Well that’s true. Competition is very big nowadays, because there are so many compositions and new compositions are appearing each day. V: Right. A: So, it’s really hard to break through. V: It would be interesting to know maybe one year afterwards, if Steve could write us his results, how many scores he sold through Sheet Music Plus or Noteflight Marketplace also. I also have Sheet Music Plus account. I also sell through them a number of my organ music scores, but not all of them. Most of them go directly through our online store on Shopify. And on Shopify you don’t owe them nothing. They just take a certain, very small percentage of the sale, and everything is controlled by you. You are in control and they are just facilitating the sale. Neither Shopify or other platforms guarantee you success in finding customers. That’s the biggest challenge nowadays... A: True. V: ...when selling is so easy. A: So, I guess the best is to compose music that you can perform yourself. V: Right! Your music has to spread. And who else will start spreading your music besides you. Of course yourself. A: Because if you don’t want to play your music, then maybe others won’t play too. V: Right. That’s how I started. Either with improvisations on Youtube or recordings of my scores on Youtube too, so other people could listen to that and then play it if they want. So having a big social profile is really important nowadays and constantly updating, constantly, basically, developing new scores. Maybe having a procedure to produce one score a month, or maybe one score a week. And then a year later you will have large catalog of your works already. And bigger chance of success too, the more you have. A: True. V: Okay guys. These are our thoughts about that. If you have any other feedback, please let us know. And please keep sending us your wonderful questions. We love helping you grow. This was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: And remember, when you practice... A: Miracles happen! |

DON'T MISS A THING! FREE UPDATES BY EMAIL.Thank you!You have successfully joined our subscriber list.  Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas

Authors

Drs. Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene Organists of Vilnius University , creators of Secrets of Organ Playing. Our Hauptwerk Setup:

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

This site participates in the Amazon, Thomann and other affiliate programs, the proceeds of which keep it free for anyone to read.

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed