|

It's a cunning trick our Resistance uses against us. When we compare ourselves to the masters, of course, our level seems to be way too low. Of course, the masters seem to be unreachable, so we are all set - we can stop practicing, we shouldn't even try.

A better way to use this comparison is not as intimidation but as inspiration: "Somebody else has tried and failed, tried and failed until they succeeded, so I have a chance, too." You may not be good enough to play very advanced music splendidly today but you are definitely good enough to be generous, persistent, and create art that matters to the people around you. "I'm not good enough YET." Big difference, isn't it? [Thanks to Serena for inspiration] Sight-reading: Allein Gott in der Hoh' sei Ehr, var. 1-4 (p. 5) by Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck (1562-1621), the Great Orpheus of Amsterdam, also called Maker of German Organists (Deutsche Organistenmacher). Hymn playing: Awake, My Soul, And With The Sun

Comments

A fear of making mistakes when playing in public

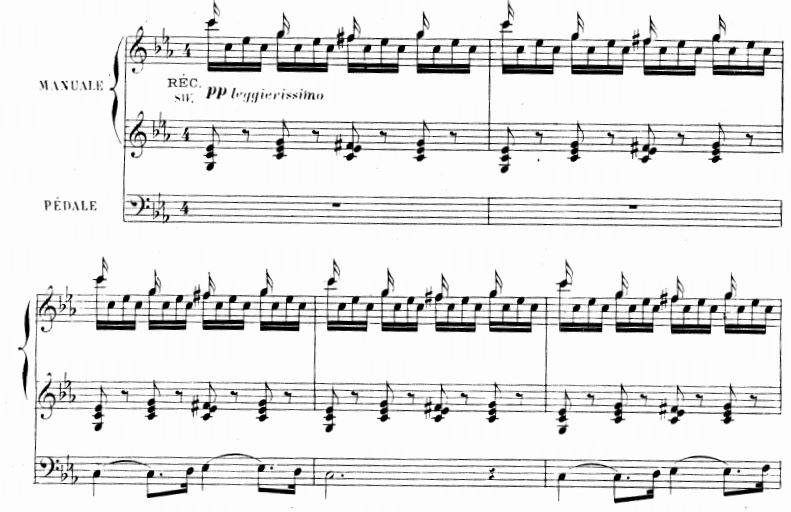

A fear of forgetting the music when playing from memory A fear of not being able to coordinate left hand and pedals A fear of leading hymn singing too slow, too fast, too loud, or too soft A fear of not having enough time to prepare for recital or church service A fear of not being liked A fear of not being noticed A fear of not reaching your full potential A fear of breaking trust A fear of wasting an opportunity to be helpful and generous, to inspire and to lead Which fears would you choose? Which ones would you like your colleague/boss/friend/family member to have? Sight-reading: Part IV: Toccata (p. 13) from Suite Gothique, op. 25 by Leon Boellmann (1862-1897), French Romantic composer and organist. Hymn playing: Angel Voices, Ever Singing Your recital or church service is over and it went remarkably well.

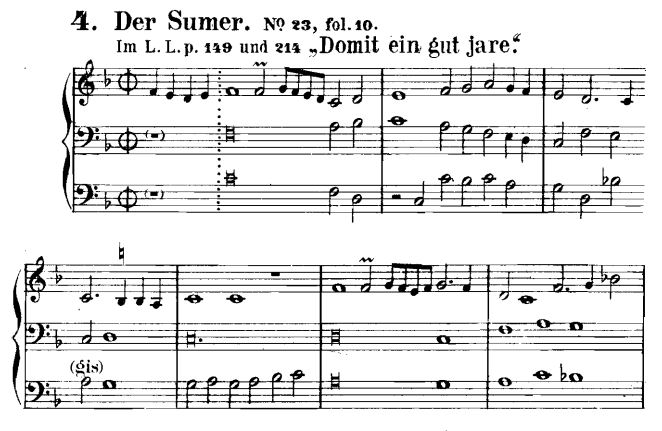

Here are one of the two emotions you might feel: 1. Joy - you've done everything in your power to make it remarkable. 2. Disappointment - you got lucky (this time). Sure, some of us are more talented than others, started earlier, have more experience, and a better technique which might get us through the difficult situations with confidence and grace. This does not extinguishes our curiosity of how much better we could have played and connected with the listeners or congregation, if we did all the homework the right way. Luck isn't everything. Honesty is. [Thanks to John for inspiration] Sight-reading: Der Sumer (p. 27) from Buxheimer Orgelbuch (ca. 1450), a German Renaissance collection of organ music. Hymn playing: And Can It Be Tom writes that his dream is to achieve technical confidence and express the beauty of the music and liturgies that he plays. The three things that inhibit his progress are that sometimes he lets time constraints win over discipline, problems with accurate pedal playing, and getting beyond always having to prepare what he has to play at the next mass.

If you are in a situation like Tom, you probably feel a fair amount of fear. A fear that your won't be able to play the pedals without mistakes when needed; a fear that you won't have enough time to prepare for the liturgy; a fear that when you don't have enough time to practice the right way, you'll take shortcuts and sacrifice the mental toughness you have accumulated over the years in favor of the panic that sets in when you feel the pressure. If you really want to advance to a whole new level in organ playing, one day in the not too distant future you are going to face your worst fears and see what you are really made of. You are not going to try finding an easy way out, you are not going to turn around and run, and you are not going to change your goal. What you really need is to feel your fear, acknowledge it, and look straight into the eyes of the thing that scares you the most. This is how you overcome fear and move to the next level. It's not easy. I remember my fear I had when I first started to improvise full-length recitals in public. I feared that I would not be able to improvise for a full hour; I feared that my improvisations are going to be boring; I feared that I would miss the time-marks and go way over the limits of the 60 minutes; I feared that I would not be able to change the stops by myself. I had no choice but to face my fears. A deadline was set. The day came. I sat on the organ bench and played. It was scary at first. The waiting for the recital was scary. The beginning of it was scary too. But I had to keep going - you can't just stop and leave the church in the middle of the performance, can you? I had to figure it out. Interestingly enough, it was easier and easier after the half-time mark. After that I knew it could be done. And so likewise, you, my reader, have to just do it, simply open your eyes and see it through what you fear the most. There is no magic to it, only determination and will-power. After that, you will be changed. What's the thing you fear the most in organ playing? Sight-reading: Part II: Adagio doloroso (p. 11) from Organ Sonata "Appassionata", Op.57 by Johan Adam Krygell (1835-1915) who was a Danish organist and composer of the Romantic period. Hymn playing: All Hail The Power Of Jesus’ Name William writes that his dream is to able to play the organ well enough to serve as a parish organist when needed. The three big obstacles are arranging his time to allow more consistent practices, focus while practicing, and coordination.

When you have such a dream as William has, it inevitably involves learning a fair amount of pieces to gradually build your repertoire. Apart from being a crucial side of learning experience, this can also be a temptation which might lead to failure to reach your goal. Let me explain. Every day, when we practice, we encounter new pieces, new delightful compositions that would be worth practicing. While for some people these pieces might go into the list called something like "to learn in the future", for others it's a shiny object. It's a distraction from your current project. So what happens is that a person jumps from piece to piece without ever learning anything in a deep way. And I'm not talking about real sight-reading practice which I'm a big believer in. Ideally, sight-reading should be done in addition to your regular practice. To prevent these temptations from harming your long-term goals, here's what helps me: Give yourself a deadline with some stakes involved. A date in the not-too-distant future which will hold you accountable. This might mean a recital, a concert, or a church service or anything like that which would involve you playing for other people. If you don't want to play in church, simply promise you will play something special for your spouse or a friend at home after dinner. Set this date together with them. When you give yourself a due date, everything that isn't a part of your current goal suddenly fades away as non-essential. This is because you know - the consequences of not meeting your deadline would cost you more than the pleasure of jumping from one wonderful piece to another. A deadline is a single most important thing which helps focus your practice, find time for it, and stay on course. If you "innocently" postpone this deadline - your goal will also move away from you. Sight-reading: Duo V Ave maris stella (in Versets of 2, 3 and 4 voices, Fabordones, Intermedios, p. 5) by Antonio de Cabezón (1510-1566), a blind Spanish Renaissance composer and organist. Hymn playing: Holy Ghost, with Light Divine Afonso writes that he wants to become a master organist, like Olivier Latry, Daniel Roth, Philippe Lefebvre, Jean-Pierre Leguay, Jean Guillou, or Pierre Pincemaille and to play a great Cavaillé-Coll instruments such as at Saint Sulpice, Notre Dame, St. Ouen, and to study at the Conservatoire Supérieur de Paris. His question is about whether or not can he achieve all this?

I can feel the pain Afonso has - it follows probably every organist I know (including myself). Can we become successful at what we do? Are we even worthy of success? We read about the masters of the past and present and many of us want to be like them, want to play large and important organs, be respected, feel the appreciation and connection with the audience, and yes, make a living doing what we love most. Apart from being our goal and driving force, these ideas can be our trials, too. The short answer is of course this - sure, we can become the masters like the other great organists, provided we are willing to work at least as hard, as long, and as focused as our role-models were or even more. In the midst of those trials, when we feel this pain, sometimes there comes a certain moment of bliss. It doesn't last long but the memory of it sticks with us for a long time. This is the realization that in the end it's all going to be OK. And not only at the end, but also now, as you are experiencing this moment, you are content. You are happy because at that moment you briefly experience your end-result, your goal, your dream. For me, one of such moments was just before one of my doctoral recitals at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, when I was waiting at the back of St. Paul's United Methodist Church which has a wonderful French symphonic style Bedient organ in it. About 10 minutes before the start I felt such calmness and focus, that the memory of this feeling never left me ever since. This short moment was what my dream was at the time. I can compare this feeling with the one when you first learn how to ride a bicycle - the moment when you realize that you are actually riding by yourself without the help of your mom or dad. You realize that this moment won't last long, because you will fall - you are not a master bicycle rider yet. But surely you remember this joy when you feel the wind blowing into your face and the shining sun and how proud your mom or dad was of you. Look for these moments of bliss even in your trials, even when you doubt your ability to reach your dream. In fact, if you can imagine it even for a brief moment, the chance of reaching it becomes incredibly higher. If you can imagine yourself sitting at the bench of the large Cavaille-Coll organ and improvising like the master (with as many intricate details as possible) - it's no longer a dream - it's part of the future you are creating for yourself. The future starts in your mind. Sight-reading: Part III: Andante Recit. (p. 9) from Organ Sonata No. 1, in F minor, Op. 65 by Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) who was a German composer, pianist, organist, and conductor of the early Romantic Period. Hymn playing: Happy the Man Who Feareth God  Doug Baker from Adelaide, South Australia: I must thank you again for sending so much instruction for organ playing. I wish so much that I could have had your lessons 60 years ago. It is very gracious of you to send so much information to an elderly organist. I am the delighted owner of the latest ROLAND C-380 Classic organ. Thankfully I am very fit at 85 and manage to fit in a couple of hours playing every day as well as my photography and computer interests. Doug writes that his dream is to continue improving his sight reading and playing. As he is an elderly organist he hasn't got years ahead of him like some of my younger students to apply himself to study of organ. He finds that the days pass so quickly and there's so much he wants to do. The main obstacle for him in his practice is managing time.

When you get to the age of Doug, I guess many things in life seem very different from what you feel and see in your youth. It's true that at that age, the sense that you can dream of mastering organ playing in 20 years is not realistic. It's also true that with this age, you don't have to worry about always rushing to do things that you don't need. You can enjoy every moment of your practice and don't feel the pressure some of my younger organists have while preparing works that they don't like but somebody else has asked them to. At 85, you simple are your own boss and can play whatever you love. That's the easy part. The hard part is that regardless of our age, we still have our own trials. Without them we don't learn anything. Without them we don't progress to the next level. My trial recently was to create the parts for 4 instruments (flute, oboe, violin, and euphonium) for my SATB hymn "Ave maris stella" (in Lithuanian) which will sound at St. Andrew's parish in Philadelphia in the US on the occasion of its special anniversary service. Therefore last Sunday I not only sat down and created these parts but also recorded a live video with my narration and description of the entire creative process so that some of my readers, if they wanted, could test their skills with any hymn they like the most. I only hesitated to make the choral and organ parts more varied and simply left them doubling one another. Perhaps another time. It's true, that we fail at some of our trials and that's OK. The only thing that matters is that we keep moving. Sight-reading: La Battaglia by Adriano Banchieri (1568-1634). He was an Italian composer, music theorist, and organist of the late Renaissance-early Baroque period. Hymn playing: When The Roll Is Called Up Yonder Sonja writes that her dream is to reach other hearts and souls while conveying the happiness organ and the music of its great composers bring. The three things that are holding her back from realizing this dream are bad education from her past, missed any stimulation from her environment, and her health.

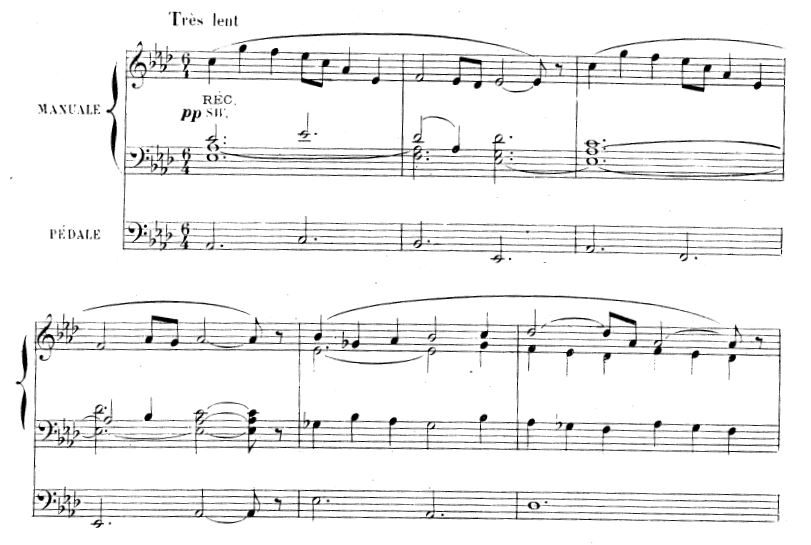

Perhaps some of my other readers feel, like Sonja that their lack of decent musical education is interfering with their efforts to progress in organ playing. Perhaps in the past they were diligent students who didn‘t have caring and experienced teachers and had to find out everything by themselves. If you are in this situation, you might experience the moments in your practice when it seems like you are not progressing. This is because based on your previous experiences you don’t actually know how progress looks like. Over a period of several months, when you take new pieces and try to master them, you still struggle at the same two-part combinations, you still miss those pedal notes, you still can’t play your pieces fast enough, and you still stumble with your musical ideas when it comes to improvisation. So you think you are just spinning your wheels. However, you will only know the true level of your advancement when you look back at your previous abilities from the distance. And when you look back, you’ll find out you don’t want to go back to that state you were before. From this place, you only want to go forward. Sight-reading: Part III: Priere a Notre-Dame (p. 9) from Suite Gothique, op. 25 by Leon Boellmann (1862-1897), French Romantic composer and organist. Hymn playing: Take My Life And Let It Be Will writes that his dream in organ playing is to play the organ music of Bach well. When he was a teen-ager, his organ teacher introduced him to the Orgelbuchlein, and he fell in love with it. He would like to go back to that, and expand his playing into the preludes, fugues, and other chorales. The most important challenge which holds him back from achieving this dream is finding time to practice.

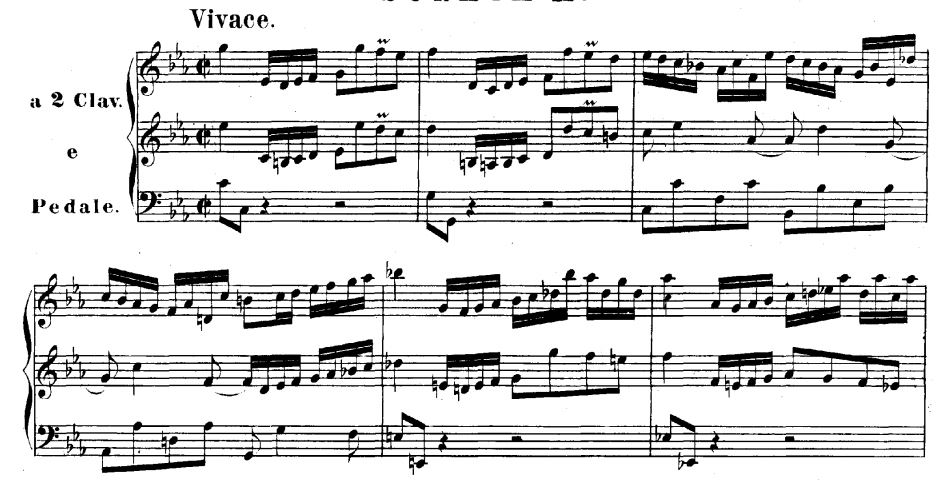

I’m sure that Will, along with my other readers who want to learn to play the music of Bach at some point will find at least some time for practice. As far as I know, for most people at least 15 minutes a day is something they can deal with (perhaps even more on the weekends). More serious obstacle is to decide what to do with that time. Therefore, a challenge which we all will face will be that very soon we will come to such a time in practice when we leave our familiar territory. Crossing the threshold to the unknown and risky state is something that is unavoidable for every curious organist because if you want to achieve anything worth achieving (learn a new piece of Bach, master articulation for his style, or compile a repertoire of various Bach’s preludes, fugues, and chorale preludes to play in church service or recital) you will have to pass beyond your comfort zone. Beyond what you have learned before and how you learned before. If your goal was within your comfort zone, you would have achieved it by now (and that wouldn’t be a very lofty goal). It will feel strange to find yourself in a situation at the instrument when you notice that if you learn these 4 new measures the correct way or analyze a piece in depth or play with articulate legato touch, your mind will tell you that this is something you are not sure will work. Something which you are not sure you can endure much longer. One part of your mind will tell you to stop while the other – to pursue your goal. If you continue to listen to your “adventurous” mind, quite soon you can look back to discover that really you are entering into unfamiliar waters. You won’t know what to expect. You won’t know what’s around the corner. You won’t know at which two-part combination you will be stuck. You won’t know, if that pedaling in extreme edges of the pedalboard you wrote in will work in a fast tempo. You won’t know how you will feel during live run-through at church service or recital. But your curious mind will want to find that out. Because your curious mind is what keeps you on the edge. Because your curious mind can’t wait to see where it all leads. Because your curious mind has helped you to achieve something remarkable in the past. Because your current comfort zone can be expanded and it will still feel and be save. Not by a leap or a jump but by one little step at a time. Will you dare to take that step? Sight-reading: Part I: Vivace from the Trio Sonata No. 2 in C minor, BWV 526 by J.S. Bach Hymn playing: Oh, Blest the House Vincent writes that his dream is to become a brilliant organist, especially in playing classical and sacred music. The three things that are holding him back from realizing his dream are the lack of his personal keyboard to practice, the lack of a specialized organist to guide him through his practice and the lack of recommended learning material like books and CD's.

Vincent chose to follow his dream. I guess it wasn't easy for him to commit, for the challenges he faces are serious indeed – if you don’t have an organ or at least a keyboard available to you, it’s much more difficult to practice regularly and efficiently (although paper keyboards and pedalboard are always a temporary solution that’s available for everyone). But he is not looking back. To become a brilliant organist will require much effort and sacrifice but he knows his life without organ playing would be less complete. I know, there are other organists among my readers who want to become brilliant organists, just like Vincent. If you are in this situation, to reach this dream will require some help – sometimes from within yourself, sometimes from external sources. I personally like to think that the first stage of learning a new piece can be seen as a help. You take a score and analyze your piece. You sort of consult with the master who created it long ago. You take this piece apart and put it back together in your mind. You analyze form, all themes, tonal plan, cadences, chords, sequences, and modulations. You also analyze all the polyphonic techniques you encounter in your composition. After this analysis you are equipped to begin to learn it and put it back together. Sometimes help also comes from the people around you. These days it doesn’t necessarily mean from a mentor or a friend who lives nearby. An online community consisting from people around the world (like this one) will help you feel that we’re all in this together and you might even get the tools necessary to learn your craft later on. If you don’t know how to analyze the piece, if you don’t know anything about harmony, about chords or music theory, you can learn. People who take action, report to me that just sight-reading these (or other) materials begins to make a difference in their skills. For example, John writes that he was surprised to find that he was able to sight-read the bass part in the pedals with the tenor in the left hand of the unfamiliar hymn, the combination that is beyond doubt one of the most difficult of all two-part combinations and was too advanced for him earlier. He also started to distinguish various chords (tonic, dominant, seventh-chords and even nine-chords) in music that he plays. Wherever you start, know you are not alone in your quest. „One should not pursue goals that are easily achieved, one must develop an instinct for what one can just barely achieve through one's greatest efforts.“ Albert Einstein [Thanks to Bill for finding this quote] Sight-reading: Part I: Andante - Allegro non troppo ma passionato (p. 3) from Organ Sonata, Op.57 by Johan Adam Krygell (1835-1915) who was a Danish organist and composer of the Romantic period. Hymn playing: May God Bestow on Us His Grace |

DON'T MISS A THING! FREE UPDATES BY EMAIL.Thank you!You have successfully joined our subscriber list.  Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas

Authors

Drs. Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene Organists of Vilnius University , creators of Secrets of Organ Playing. Our Hauptwerk Setup:

Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

This site participates in the Amazon, Thomann and other affiliate programs, the proceeds of which keep it free for anyone to read.

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed