|

A tetrachord is a row of 4 notes arranged in a stepwise motion. The distance between the outer notes is a perfect or augmented fourth. Here are the names:

1. Major 2. Minor 3. Frygian 4. Lydian 5. Harmonic I prepared a simple test where you can check, if you know the 5 tetrachords (there are 12, actually, but that's for another time). If you don't know how they are constructed - don't worry, I have given you the clues and hints in this test. Every major or minor scale and many modes are constructed out of these tetrachords so they are very useful to learn for every organist.

Comments

This question is quite important when we deal with more than one voice in one hand which have to be performed legato. Although it is possible to pick a fingering which would allow you to play legato, in reality it is not always easy to achieve. This might happen when your hand is very small or when your technique is not sufficiently developed.

In these cases, you can think what voices are the most important. First of all, the soprano line (because it is very often the most melodically developed voice) can't be sacrified. Play it legato but if you can't find an appropriate fingering for the lower voice or voices in the right hand, you can sometimes play them with detached articulation. Be careful, though that your articulation doesn't draw attention to these voices. If you have more than two voices in the left hand, I think the lowest voice becomes the vital part here. Try to play it legato and if you must, the upper voices can be detached. Because the bass part is the foundation of the harmony, try to play it legato at all times (when the style requires it). Sometimes I hear some organists play the pedal part with detached articulation while the upper parts are performed legato. Often this is due to poor choice of pedaling. Try to work out the pedaling so that the result would be a smooth legato. Employ both feet (toe and heel) when you have to. Please note that the above tips apply only when the general performance style is legato (for Romantic and Modern music). But even then there are certain cases, when some notes should not be played legato (you can read about it here). Because in early music we use the articulate legato touch, these tips for the most part don't really matter for Medieval, Renaissance, Baroque and Classical organ music. If you struggle with learning a piece of organ music, check if you are not missing any steps. Here is what I mean.

Some people learn a piece in 7 steps: 1. Right hand 2. Left hand 3. Pedals 4. Both hands together 5. Right hand and pedals 6. Left hand and pedals 7. Everything together This works in cases when the piece has 3 parts or is largely homofonic in texture (melody plus accompaniment). But when there are 4 parts and the piece is polyphonic in nature (with 4 independent parts), it would be better to take 15 steps: 1. 1 2. 2 3. 3 4. 4 5. 1 and 2 6. 1 and 3 7. 1 and 4 8. 2 and 3 9. 2 and 4 10. 3 and 4 11. 1, 2, and 3 12. 1, 2, and 4 13. 1, 3, and 4 14. 2, 3, and 4 15. 1, 2, 3, and 4 I know how tempting it is to skip these 8 steps in four-part music. But if you think about it, often it's a leap from 1 part to 3 parts without working on many of two-part combinations. Do you go from A to D without touching B and C? If you do, you're a genius. But if you're not (or not yet), it's better to do it step-by-step. Have you had a strange situation when you play a piece with correct rhythms but suddenly start to double the rhythms in half? In other words, almost like without a reason (it seems) you begin to change the rhythms so that instead of quarter notes you play half notes or vice versa.

It can be really frustrating, especially if you don't know the piece very well, record yourself and you notice this strange rhythmical alterations happening. If this has happened to you, I know how you feel. In fact, just yesterday I saw one of my organ students do it right in front of my eyes (which of course inspired me to write about it and offer a solution today). The reason sometimes we do it is that we lose the sense of a pulse. In other words, we get so preoccupied with the notes and playing the right rhythms that we don't notice how we change the pulse from one rhythmical unit to another. Or sometimes we even forget to feel the pulse of the piece at all. The simple fix to this kind of mistake is to start counting out loud the beats of the measure. For example, in 4/4 meter you would say "One, two, three, four" or even "One and two and three and four and" with eight notes, if you want to be even more precise. I didn't say it's an easy trick to do. Yes, it's simple, but it's extremely difficult to force yourself to say the numbers out loud while you are playing. Your mind will find all kinds of excuses, such as "I'm not ready for this yet; let me first learn the notes right and then I will worry about the rhythms and pulse; I can count in my head silently and play in time" etc. Some of these excuses will even partially be true. But if you really want to change the way you keep a steady pulse, do it for while - count out loud the beats and their subdivisions. Doing it aloud will force you to play in time. This kind of problem normally doesn't happen to people who sight-read regularly and systematically. Somehow the breadth of the repertoire they encounter every day puts them in a mode when they can sort of feel what will be coming up next in the piece. Therefore, illogical things like doubling the note values without a reason will simply be out of question to you. Among other things, sight-reading expands your musical intuition which can be very useful if you have serious goals in organ playing. We know that the better approach to learning a new piece (especially at the beginner's level) is not to play the piece from the beginning until the end or play all parts together right away.

Yet I see some of my students do it all the same. I know these are efficient practicing techniques and I could prove from many examples in my or other people's practice that they do work. So the question is why we still practice the wrong way when we know there is a better (not necessarily the best) way? I think the answer depends on several factors: 1. Worldview 2.Trust 3. Care 4. Resistance The person whom we want to change has a different worldview than we. In addition to that all interactions are based on trust. If the person trusts us, does he/she cares enough to listen to what we have to offer and take action? And finally, even if this person trusts us and wants to take action on what we have said, he/she still has to confront his/her own internal resistance. We can't really change a person's mind to start practicing the way we believe is a better way. The change has to come from within. Yesterday during the rehearsal of our organ studio "Unda Maris" at Vilnius University, one student (she is over 50, I think) came in very different than for other times. I didn't know what it was right away but there was something different about her playing.

I came in the studio first and started all the necessary preparations - turned on the lights, the organ etc. and she came in shortly after me. After asking whether she was the first one to show up today, she sat down on the organ bench, pulled a few stops and started to play the Prelude in C major, BWV 553 from the 8 Short Preludes and Fugues that we all know so well. What was remarkable about her is that she didn't start how many students do - with trying out a few stops, a few notes, a few passages with their hands and/or feet. She just sat down and dived right into the piece as if she was playing it before sitting down. She didn't play without mistakes, though and this is not the point I'm trying to make. After her playing I asked her about what was different about her this time and she replied that she practiced in her mind while sitting on the bus on her way to the studio. That made sense - we all know how long it takes for our minds and bodies to warm up - at least 10-15 minutes (often even more than that) before we can start doing our regular work. But because she had practiced on the bus in her mind, she came in to the studio very targeted with a laser-sharp focus. She knew what she has to do, she knew how it should sound etc. I think there is an important lesson for all of us here. If you need to play in public during church service, a recital or a lesson, try to focuse your mind before it. Try to practice in your mind ahead of time the piece or the pieces you will be performing. This may mean you need to memorize your compositions. Not only it saves time but it actually helps in performance. Interestingly, you can apply this approach in any aspect of your life, too. Be ready before the time comes and you will never be in peril. Recently while waiting for someone in my car I had my camera with me, so I decided to do a video about some of the mistakes people make when harmonizing chorales. Thanks to Judith for a question about this which inspired me to create this video.

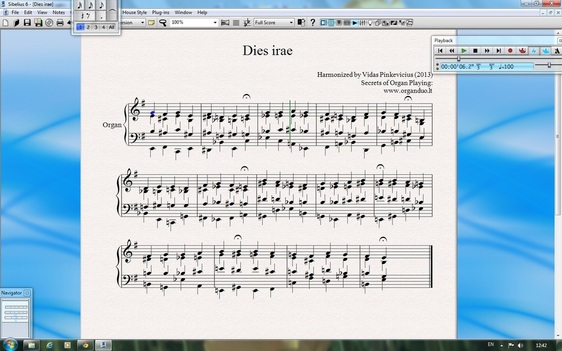

In order for your harmonizations (written down or improvised) to sound as natural and logical as possible, there are some important rules and breaking these rules often leads to less than satisfactory results. I have taken these points from the actual examples I see students make at M.K.Ciurlionis National School of Arts in Vilnius where I teach so you can be sure they all are practical and down-to-earth. Chances are you might be making them, too. In reality these mistakes are not that difficult to avoid but you have to be aware of some of the methods and techniques that I talk about in this video. I hope this video will be useful to you. After you watch it, take action and apply my tips in practice with the hymn or chorale tune of your choice. Yesterday I shared with you the harmonization of Gregorian chant sequence Dies irae in four parts. What was unusual with this exercise is that the chords were in the style of 20th century French modal organ composers. If you haven't seen the score, here are the PDF and MIDI files.

After this post a few people asked me to describe the rules of this type of harmonization so that they could learn to harmonize like that themselves. So today I decided to go into greater detail of how I do it. 1. Use three note major and minor chords only (such as C-E-G or A-C-E). 2. In four-part setting, double the root of the chord (in C major chord, double the note C). 3. When the melody descends, use closed position of the chords, when the melody ascends - open position. 4. Whenever possible, avoid parallel movement in all parts within the sentence - use as much contrary motion in the bass. 5. At least one voice has to be stationary or go to the opposite direction that others. 6. Avoid perfect 4th and 5th relationship in the chords because this will sound like in traditional classical tonal harmony (T-D, D-T, T-S, S-T). One possible exception of this rule might be at the very ending of the piece, but even then it's probably better to find other options. In my example, the last two chords are B minor and E minor. Now when I'm thinking about it, I would change B minor chord to D major. At any rate, minor-minor chords at the end are better than major-major because this eliminates D-T feeling. 7. Instead use major and minor third relationship between two chords up or down (such as C major - Eb major). 8. Major and minor second relationship up or down is also good (such as C major - Db major). 9. A tritone relationship sounds wonderful (such as C major - F# major). 10. If you have no other choice and have to use perfect 4th and 5th relationship between two chords, let one chord be major and another minor or vice versa (such as C major - F minor. 11. It is OK to use one major and one minor chord and vice versa, if they are not closely related (not only in instances, like in No. 10). 12. In general, the wider the distance of the two chords or keys within the circle of fifths, the better. Apply these rules (in writing and/or in improvisation, because you can learn to do it spontaneously on the spot) on any hymn tune you want - chant, chorales, hymns, folk songs, even the National Anthem of your country. I'm sure your listeners will have something to talk about. P.S. We only used major and minor triads in root position and the result is pretty colorful, I think. Imagine, what would happen, if we chose their inversions or diminished and augmented chords as well as seventh-chords and ninth-chords and their inversions? The color range would skyrocket in such case. That's what all these 20th century French master organists and composers did. You can do it, too. A few days ago I visited a friend organist during a church service he was playing here in Vilnius. This was the time of the church year when they used the sequence Dies Irae. My friend's harmonization sounded so nice that this melody inspired me to create something of my own.

Although the above score looks pretty scary in terms of chromatic notes, I used only major and minor chords to harmonize this tune. The result - a little like French modal writing of the 20th century organ composers. The key was not to use Tonic and Dominant chords in this setting. Instead lots of other chordal relationships of a tritone, major and minor thirds are pretty colorful. So today I would like to share with you this harmonization in four parts. Here is the PDF and MIDI files if you want to play it. If you would like to know how to write or improvise in this style on any tune you want, please let me know. As many of you know, the Circle of Fifths is a system which lists all major and minor keys in the order of ascending number of accidentals.

If you start with C major which has no sharps or flats and want to find a key which has 5 sharps, you simply have to go upward from C by perfect fifths (a perfect fifth is an interval which has 3 whole-steps and one half-step): C-G-D-A-E-B. This means that B major has 5 sharps. If you want to find a key with 5 flats, you go from C downward by perfect fifths (C-F-Bb-Eb-Ab-Db). This means that Db major key has 5 flats. In order to find minor keys, you just have to go from the note A because A minor has no accidentals. This means that the minor key with 5 sharps is G# minor and the key with 5 flats is Bb minor. Or you could simply find the major key and then go downward by the minor third. This is another way to find minor keys. So the exercise which would help you master the Circle of Fifths is this: in each key play Tonic (a three-note chord built from the 1st scale degree), Subdominant (built from the 4th scale degree), Dominant (built from the 5th scale degree) and Tonic chords in three voices with both hands which should be one octave apart. First play the chords in the major key and then in the minor key (C-a-G-e-D-b-A-f# etc.) When you reach the key with 6 sharps, in your mind switch to the flat keys (F# major = Gb major). This way you will be able to come back to C major and the circle of fifths will be closed. I will give you an example of the chords in C major and A minor: C major: C-E-G, F-A-C, G-B-D, C-E-G. A minor: A-C-E, D-F-A, E-G#-B, A-C-E (note that in any minor key, the Dominant chord always has to sound major - we raise the 7th scale degree to achieve that). Practice this exercise tonight. This doesn't necessarily mean you will be able to master it in one day, but I think if you repeat this exercise this week, you should be able to see the real breakthrough. As a side effect, you will also master the three main chords in each key. This will prove very useful to you later on. |

DON'T MISS A THING! FREE UPDATES BY EMAIL.Thank you!You have successfully joined our subscriber list.  Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas

Authors

Drs. Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene Organists of Vilnius University , creators of Secrets of Organ Playing. Our Hauptwerk Setup:

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

This site participates in the Amazon, Thomann and other affiliate programs, the proceeds of which keep it free for anyone to read.

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed