|

Today I would like to share a video lesson I made about perfect unisons. In the video below you will find out all the theory behind this simple but important interval - how to construct it in major and minor keys, how to resolve it and how to master it.

Comments

In the 19th century, German and French organ building traditions (Cavaille-Coll and Sauer, for example) started to use progressive mixtures. The main feature of this stop is that the rows don't fall back one octave lower as the pipes get shorter and shorter, e.g. they are non-repeating. This gives a very powerful high range which is highly notable in the music of Reger when he writes many scale-like passages in octaves.

The use of the mixtures in general has to be always with consideration. Of course it belongs to Organ Pleno registration and could be used in playing free works from the Baroque period, such as Preludes, Fugues, Fantasias, Toccatas, Passacaglias and Chaconnes etc. Also mixtures can be like a crowning jewel of the organ sound in other periods as well (provided it is well voiced and tuned). Always check if the mixture is a low one in which case you would need 16' in the manual as well. Don't forget that Organo Pleno registration simply implies principal chorus. This means you can build the Pleno sound without the mixtures as well by using the pyramid of principals and mutations 16', 8', 4', 2 2/3', 2', 1 1/3' and 1'. This might be useful if your mixtures are too harsh or the piece is of a gentle character or key (perhaps some preludes in F major etc.) or if you need variety in your recital and you are playing several pieces which would require principal chorus registration. In German Romantic tradition, when you build crescendo, the mixtures come after softer reeds of the Swell division but before the stronger and more powerful reeds of the Great. In French Romantic tradition, the mixtures come in after all the reeds. A final thought: don't make a mistake I once did with the mixture of the Great on my organ at Vilnius University St. Johns church. This time I was playing a prelude in C major, BWV 547 by Bach and I thought I needed a mixture with the third sound (which would work really well for middle German Baroque). But this mixture consists entirely of repeating octaves and fifths. So I added a Tertia stop at 1 3/5'. Since this third is non repeating, the result was rather too harsh. A mixture is a compound organ stop which has several ranks (usually from 3 to 6) of metal pipes. Sometimes it consisted from as few as 2 ranks or as many as 10 or more ranks (for example, on the Hauptwerk in the 17th century Dutch tradition).

Normally it has ranks with repetitions at the octave and the fifth but some mixtures have also an interval of the major third (especially in the middle German Baroque tradition or England). This stop can have many versions and may be called Mixtur, Mixtura, Rauschpfeife, Cimbel, Cymbal, Cymbel, Gross-Cymbel, Scharf, Furniture, Fourniture, Plein jeu, Plein jeu harmonique, Progressive, Sesquialtera (in England) or something similar. I guess the mixtures is the relic of from the older late medieval organ which didn't have separate stops and only relied on large principal chorus (with mixture sound). This was called the Blockweck. It could have as many as 50 or more ranks of pipes for one key and multiple bellows. Because mixtures tend to be quite high-pitched stops, as they ascend through the keyboard range the pipes begin to be too small to handle (and to listen too) and so usually the highest rank drops down one octave lower (sometimes to the closest fifth). High-pitched mixtures can based on 1 1/3' or 1'. In the lower range, the mixture can have more ranks but fewer in the upper range because the highest rank in the top can drop out when the pipes are too small and the pitch is too harsh. In Italian tradition the organ lacked mixtures but had principal stops at octave and fifth pitch level going all the way from 8' or 16' to as high as 1/3'. Drawn together (this is called Ripieno) they resemble the traditional Organo Pleno sound with mixtures. The low mixtures (based on 2' or 2 2/3') are best used together with the 16' stops on the manual because these lower pitches can interfere with the foundation stops and could make the basic notes difficult to distinguish. Some mixtures on the pedals can be even lower based on 5 1/3'. By the way, the pedals can even lack mixtures but the low fifth sound of 5 1/3' or 6' as written in some cases (combined with 4') will give the impression of the mixture sound. Here I must also add that even the pedals can have high-pitched mixtures in some traditions such as Baroque in the Netherlands. The low fifth of 5 1/3' used together with other lower stops can also give the impression of the 32' in the pedals. This is an interesting phenomenon. Traditionally mixture sound is the crowning glory of the organ. But (and this is a big but) they have to be well-voiced and well-tuned. Otherwise many people (not only listeners with hearing aid) will be angry with you for using them (and some will not like them anyway).

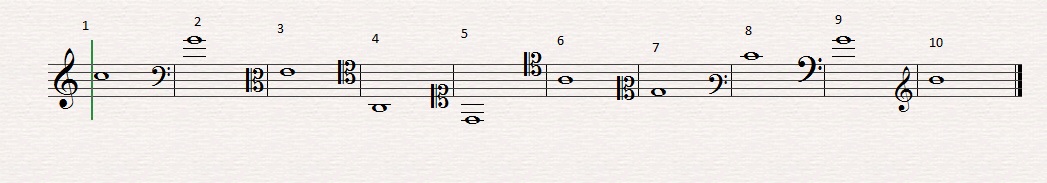

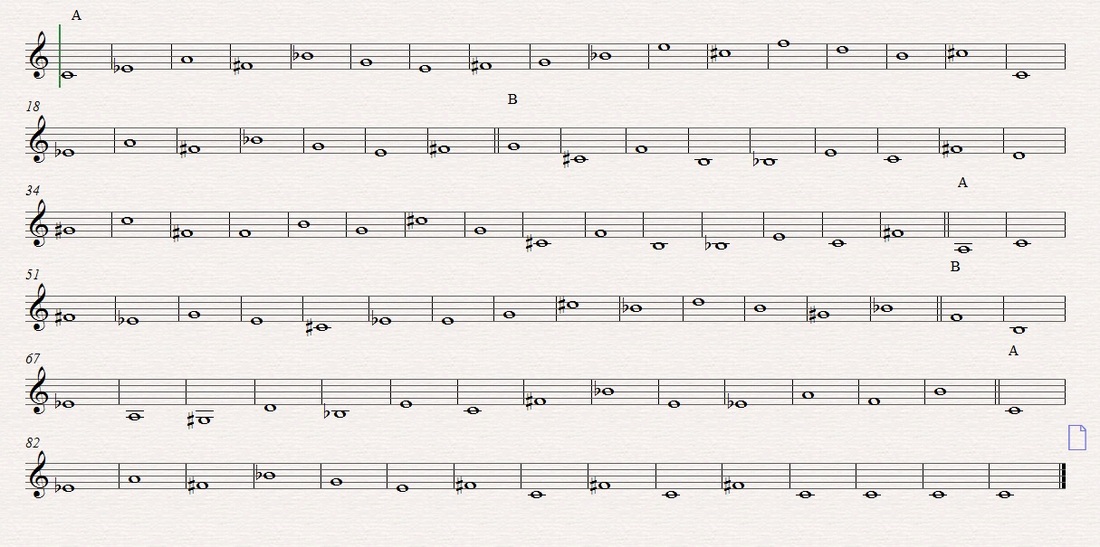

Even though you can see 10 different clefs in the above picture, in reality there are only 3 kinds of clefs: G, F and C. G clef (as in Nos. 1 - Treble clef and 10 - Descant clef) indicates where is treble G (or g'). F clef (as in Nos. 2 - Bass clef, 8 - Baritone clef and 9 - Basso Profondo clef where is tenor F (or f). C clef (as in Nos. 3 - Alto clef, 4 - Tenor clef, 5 - Soprano clef, 6 - Baritone clef and 7 - Mezzo soprano clef) indicates where is treble C (or c'). Today I have prepared an outline of the improvisation that you can create in ABABA form.

Choose any meter, tempo, rhythm, registration, octave and texture and play something interesting exclusively out of major chords built on these notes. In order for the B part to have more contrast with the A part, you can choose some other musical elements listed above (different meter, tempo, rhythm etc.). Here is the PDF file for printing. The other day I was talking with a security guard at my church when another organist was rehearsing for the upcoming recital. At that moment the organist happened to play a very harsh-sounding piece with lots of super-dissonant chords and everything was registered with bright mixtures.

But the security guard was pretty upset by the sound this organist was creating and said the sounds reminded her of a situation when an organist plays clusters with his elbows at random. I should add that this guard loves organ music in general, she loves my rehearsals and says she could listen to them all day (and night) long. And yesterday I received a message from my friend Marcel from Canada who in his own words also recounted similar stories with mixtures (people leaving the recital or going to the part of the church where high-pitched screaming mixtures would not be a problem). Some people hate sound of the mixtures. Let's consider why. Let's start with raising a question such as this: if I was playing a similar piece, how this security guard would have reacted? She loves how I play so she naturally might be predisposed to like even sounds and pieces that normally she would refuse to listen to (her story would be something like this "Vidas plays this piece so this must be good music and a great sound. If I don't like it, it's my fault so I should at least tolerate it"). Many of today's modern organs have mixtures which are too harsh for the environment they are in. We must remember that when we register a piece. In this case it might be that even some organists rightly hate such mixtures. That's why it's better in some situations (if the range permits) to play some pieces one octave lower (like Toccata by Widor) to reduce the effect or to omit mixtures but add a few of high-pitched stops and mutations. Then there is a question about people with hearing aid. I heard an opinion from Prof. Quentin Faulkner at the time I was studying in US, which resonated with me that harsh mixture sounds clash and interfere with hearing aid. In other words, because hearing aid lets a person hear sounds louder, these mixtures simply become unbearable. I think we as organists should take great responsibility of what we play and how we play and register the music we play in public. In some extreme cases people who hate mixtures might start to hate organ and its music in general. When we choose a repertoire for recitals, we must think about the instrument, about the people and about the occasion and aim to have balance between loud and soft, joyful and sad, high and low sounds, fast and slow pieces. Maybe then a little of harsh sound of mixtures interspersed with flutes, strings, principals and reeds will be interesting enough and not become a burden to some of our listeners (and ourselves). PS. Avoid practicing on your own with harsh mixtures all the time (even when the piece demands it). They may indeed be harmful to our ears. One or two flutes is usually sufficient. Remember this - practice is not rehearsal and certainly not the same as performance. If that's your recurring thought, you are trying to solve the wrong problem.

If your organ improvisations or compositions suffer from the lack of creativity, the solution isn't to figure out some way to invent a lot of musical ideas, figures or more textures. Those are the solutions, based on the notion that what you doing isn't sufficient, isn't interesting and isn't inventive. The challenge with this approach is that it is very difficult to control it. You can get tons of new ideas, find hundreds of figures in the pieces of other masters but the question is what are you going to do with them? Soon you will get lost in all the wealth of musical material that comes your way. No, the solution lies in using the musical ideas that you already know and building something interesting out of them. If you only know one chord, that's plenty to start with. Go play with this chord in any key, in any intervalic relationship to find out which solution sounds worth remembering and which one - not so much. When you do that, when you improvise for 10 minutes just using this chord (regardless if some part of your brain screams at you to stop), then little by little you will discover new interesting ideas and musical elements that you can put in your "bag of tricks". No, it won't be a perfect sonata or a set of variations that gets listed on the top 10 most important pieces ever written. But yes, you can drammatically solve the problem of "more creativity" by mastering musical elements that you already know and controling them in a creative way. Everyone is creative. In fact, we are too creative. More important is deciding to use the creativity you already have and share it with others. Finding the best fingering for music composed after 1800s might often seem like a great burden for many organists. The problem happens when you write fingering considering only isolated notes and not connecting them into passages.

Here is how you can think about fingering for Romantic and Modern organ music: If the fingering is for a single-voice melody in one hand, remember the scales, arpeggios and chords. This will help you find the best starting point and position. When you have more than two voices in one hand, in order to maintain a smooth legato, you often have to apply finger substitution and finger glissando. The easiest way to learn to apply them is to practice playing scales in double thirds and later in double sixths. Obviously, technically they are quite challenging to play so you need to learn basic scales in octaves, thirds, tenths and sixths before that. In reality, writing in fingering is a simple task, if you have experience with scales, arpeggios and chords (at least T, D7 and VII7). So if you are having trouble in discovering the best fingering for music composed after 1800s, it may mean you need to play more scales, arpeggios and chords in the keys that this music is written in. Do you want to see a proof of this statement? Create a simple experiment. Choose a piece that you would like to master but which has (appearently) difficult fingering. Play it once. Count the approximate number of mistakes. The result should be quite messy. Then learn to play the above mentioned scales, arpeggios and chords fluently in the keys of your piece in the average tempo. The number of keys will be more than one bacause you will most definitely find quite a few modulations within the composition. For some people it may take a week, for some - a month or even more. But it will be worth it, because a) you really like this piece and want to master it and b) this experiment will show you how scales, arpeggios and chords can help you with your fingering (an with your general technical level). Don't practice this piece for the time you are learning the scales, arpeggios and chords. Only after you can do it fluently, go back to this composition and try to play it (or write in fingering). If you practiced honestly all this period, the result will surprise you in a good way. I'm sure many of my readers would agree that the best feeling for an organist is when one plays a mechanical action (tracker) organ. On such instrument you have a direct control of the touch and speed of the opening of the pallet box. However, some such organs (especially the large ones) have the keys which are difficult to press. Add to this mechanical couplers and you can see why an organist has to have a fairly well-rounded finger technique.

Another difficulty playing tracker organs is mechanical stop action. Every stop has to be pulled and pushed by hand and sometimes it's not very easy thing to do (especially when you have to change several stops at a time). Wouldn't it be great if an organ could preserve mechanical key action but add an electric (or solid state) stop action where you could also have thumb pistons, toe studs and multiple memory levels? As a matter of fact, plenty of modern organ builders choose to build such instruments. It can be technically easily achievable. My organ at Vilnius University St. John's church where I work doesn't have stop combination action. Every stop has to be changed by hand. The stop handles are fairly large and it's a heavy job for an organist to change registration. In this case, I often advise organists who play here to choose the repertoire wisely. Some pieces need even two assistants changing stops on either side of the console. Do I wish that this instrument had a stop combination action? Not at all. I love it just the way it is and think deeply about what kind of music can be best performed here (keeping this in mind, there are far more choices than it is evident at first). But if you happen to play a tracker organ with stop combination action, your registration choices can be (almost) unlimited. Today I have prepared a special exercise for you - a 3 part setting of the hymn tune "O Lord, how shall I meet you" in Bb major. In this exercise, the choral tune is presented in the soprano played by the right hand part. The left hand and pedals move in eighth-note rhythms with imitations. Practice this exercise in a slow tempo repeatedly until you can do it 3 times in a row fluently. You may have to play separate parts and combinations of two parts before putting everything together. Intermediate level organists: transpose this exercise a whole step higher to C major. Advanced level organists: transpose this exercise a whole step lower to Ab major. Here is the PDF file for printing and a MIDI file for listening. When you are done practicing, post your time to comments. |

DON'T MISS A THING! FREE UPDATES BY EMAIL.Thank you!You have successfully joined our subscriber list.  Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas

Authors

Drs. Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene Organists of Vilnius University , creators of Secrets of Organ Playing. Our Hauptwerk Setup:

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

This site participates in the Amazon, Thomann and other affiliate programs, the proceeds of which keep it free for anyone to read.

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed