|

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start Episode 193 of Ask Vidas and Ausra podcast. This question was sent by Jasper and he wrote: Thanks for the recordings of the BWV 669, 670 and 671 choral preludes. I purchased your 671 fingered score a couple of months ago and have had much enjoyment playing through it (very slowly). I am treating it more as an exercise in multiple parts as I cannot see myself playing it at listenable tempo. Incidentally, one thing I had to do was to white out all your fingering with correction fluid and print it back in freehand to a font size that my poor eyesight could cope with. One question I have: how do you recommend practicing to bring out the individual parts? Just playing it through to get the fingering and notes correct must sound awful unless the parts can be articulated. To deal with this problem I assume two methods: one to play each part separately – although this is not easy with so many parts together on the printed score. The other seems to be to play everything but to concentrate on just one part at a time and ensure that at least that one ‘sings’. Jasper V: So Ausra, first of all Jasper played Kyrie, Christe, and Kyrie from Clavierubung Part III by Bach, and he seemed to enjoy the recordings and he recently played the last Kyrie right? The five part setting and that’s a very thick texture. A: Yes, it is but it’s very beautiful too. V: He had to adjust my fingering a little bit to enlarge it right, because his eyesight is poor and he had to have a bigger font. So his question is about listening to individual parts, right? That’s a tricky question. A: Yes it is. V: Do you remember the time when you last played this piece. Did you have to do something special or articulation came more naturally for you? A: Well it came quite natural although this chorale is not that easy to do because it is very chromatic and as you said earlier it’s a thick texture. But I had to practice each single line of this particular chorale. Usually I practice individual lines when I’m working on fugues. V: Um, you know if you have a trouble to articulate thick texture it means just that this piece is too difficult to you. A: Could be. Could be. V: I would go back to the like three part texture or at least four part texture. You know because five part texture is something that has to come very naturally. When I played it for myself a few weeks ago yes I slowed down the tempo quite a bit, made it very very slowly and that saved me of course a lot of time. But I also didn’t practice each part separately. I listened to each part separately, yes, but I didn’t have to do all those separate parts because I prepared my homework you know for many years before. A: Yes. Another thing that might help I think singing each line would help too. V: He didn’t say Jasper about singing but he says to concentrate on just one part. He sort of concentrated, focused on one part at a time. And you suggesting basically to sing it, right? A: Yes. V: That would probably help him a lot. I remember another trick I think my first organ teacher suggested to me. She was in Eduardas Balsys at the Art School, Elena Paradies I think her name was. She said you could play with silent keyboard, you know, one part and louder with the others, you know. The part you need to concentrate on you could first play louder that the others and then do the opposite, make it much softer that the others. A: But I don’t think it would work for this chorale because you play all voices on one manual so how would you put it into a different manual? V: Most of the time though, you could do two voices in each hand, most of time, not always. So then at least two parts would be softer and two parts would be louder. But it’s not perfect solution obviously. You suggested better I think right? To sing. A: Yes and of course articulation. Doesn’t matter how many voices you play you must articulate each of it. V: Well let’s assume that Jasper is so motivated to play this piece that he can do all those individual lines first, right? It will be more than sixteen combinations, maybe twenty something. Over twenty or even thirty. I haven’t counted all the individual solo parts, then two voice combinations, three part combinations, four part combinations, and only then, you know, five part texture. Maybe he can do that but not everybody is so focused, right? A: Yes. V: But then you see he has to sing any part. Soprano, second soprano, alto, tenor, the bass in his range. A: Yes, that’s true but I also mean that you must play all other voices you know, while you are singing one. V: Ah, you are not suggesting that you omit that voice which is being sung. A: No, no, no, no. Because I think it’s very important to practice in this kind of thick texture that you will get used to it and you could control your touch Ordinary Tuch. V: If this was a training exercise you would omit. A: Sure, but not in this case. V: You would omit the part you are singing. A: Because look, if you will omit one voice that you are singing for example you might ruin your fingering and it’s important to play with the same fingering all the time because you know, fasten up your progress. V: Um-hmm. What if he uses you know, our scores with printed out fingering and pedaling and can then play let’s say one soprano and another to sing with correct fingering? A: Well yes and no because still the position of the hand will be different while playing one voice. V: Mmm. Your right, your right. A: So I would say you know, practice all voices together. Maybe not all voices together but right hand, left hand, right hand and pedal, left hand and pedal, and then both hands together and then everything together. That’s what I would do. In slow tempo and sing each line. V: And if it’s really really difficult or too difficult like huge mountain, like Everest in front of you then I think you should do a few easier pieces. A: Yes and you know if you like this particular collection which I personally do I would suggest that you don’t start with large chorales. You could perfectly do those little ones. V: and duets. A: And duets, yes. And you know those little chorales are just wonderful pieces. Excellent examples of you know baroque writing and baroque composition and know these three kyries. I remember playing them in a concert actually those little ones in Lincoln. So, I think they are wonderful. Vater Unser is wonderful example of you know chorales, the short ones. V: Um-hmm. Did you have fingering written out for those pieces or not? A: Well maybe just a few spots you know for those. V: Um-hmm. A: But you know if you are a beginner organist I would suggest you write down fingering for those pieces as well. V: We haven’t prepared such scores yet for you but in the future we hopefully will so stay tuned for that if you are you know, eager to play with our fingerings which produce natural articulate legato almost without thinking. OK thanks guys this was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: Please send us more of your questions. It’s a really fascinating discussion we are having here with Ausra. We love helping you grow. And remember when you practice… A: Miracles happen.

Comments

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 158 of #AskVidasAndAusra Podcast. And this question was sent by Steven. He writes: Good morning Vidas, Thank you for posting the explanations, guidance, and helpful suggestions in the "Ask Vidas and Ausra" series. I would also like to submit a question to this series, if I may ... Organists today know to use articulate legato (so-called "ordinary touch") in all the parts when performing early (pre-1800) organ music, such as the fugues of Bach and other polyphonic pieces, and to employ legato and all of its associated techniques for all organ music written during or after the 19th century, unless otherwise specified by the composer. It's conceivable though, that in the course of our studies we may run across a polyphonic piece, such as a stand alone organ fugue, written pretty much in 18th century common practice style by a modern composer ... where the music is very busy and actually sounds in places like it could have been written in the last half of the 18th century by an acolyte of the Bach school ... and the score has no indications about the touch. All we know is, it was written in the 21st century. In this situation, how do we determine a starting place for the touch? ... do we follow the rule that the date of composition in each and every case determines what kind of touch should be used and employ legato in all the parts as a starting place ... or should we take the polyphony of the piece into consideration and employ articulate legato from the beginning to keep all the moving parts clearly audible to the listener? I was wondering how you and Ausra may feel about this ... whether the music's date of composition should be considered more important than it's style when choosing a starting place for the touch. Thank you once again for all the help, aid, and assistance, it's much appreciated. Steven V: As I understand, Steven asks about the situation when a person creates a modern composition but written in the old style, right Ausra? A: Yes, and that’s what I understand from the question. V: And what should the touch be? What’s your opinion today? A: Well, you know, if it’s written in baroque style, let’s say a fugue in baroque style, I would use ordinary touch. That’s my opinion. What about you? V: It’s the same as improvisation, I would say. Whenever we improvise in the historical styles, we use the touch of those styles, even though it’s improvised today, in the 21st century. Right? Somebody could even record this improvisation and transcribe it into musical notation and make it a finished, polished piece, and it would sound like more or less early composition but created today. A: Yes, because I think the style is more important the the date that the piece is written. Because nowadays all those styles mixed up together and you can create whatever you want. And if you feel that sort of style is more close to you, or you are more related to it and you create compositions like this then they definitely have to be performed with ordinary touch. That’s my opinion because otherwise it might just sound muddy and unclear. V: I’m just trying to think of any recordings that I heard recently when improvisation was done in the old style by living of course performer. But none come to mind, right, because every good improviser knows the difference of touch in historical styles and tries to emulate that touch. Although, in the past might have been some people who played baroque style polyphonic pieces like that. But that’s because everyone else was playing legato at the same time, baroque pieces. Right, Ausra? A: Yes. I think so because just tendencies are like this in those days and everything changes and we have talked about in earlier podcasts. V: Yeah. I just remember now, one instance I wrote seven chorale improvisations very early in my career. I think just after graduating from UNL, and those were based on my improvisations. I recorded them and transcribed them into musical notations, and then I thought maybe somebody could publish them, right? That was before the days of this blog of course, because today I would just post it from the internet to myself, and send it to Wayne Leupold Editions, and after while I receive and answer, a very nice polite answer, that, ‘it’s wonderful that you are interested in submitted for possible publication’. And those pieces could be considered in the stye of Crebbs I would say, not Bach, but a student of Bach, let’s say. So when Leupold wrote that, however nobody can really compete with Heir Bach, Master Bach, right? So he doesn’t see or didn’t see the point of publishing early sounding pieces today where there are thousands of original music written. So I stopped doing this, of course on paper. Maybe on the instrument is a another story, when you improvise. What do you think about that Ausra? A: Yes, actually, you know, it’s better probably to leave that early style for improvisation already, instead of composing in that kind of style, but of course we have free will to choose for ourselves. V: Exactly. Let’s say Bach would have thought the same and would try, would have tried to imitate styles of early composers who came before him. And he did actually. A: He did, actually, yes. V: But while doing that, he did this very creatively and combined several styles in one piece; Italian, German and French. A: And actually yes, you can hear in his compositions and see and hear the early styles Stile Antico, so called, and you know the baroque, high baroque style. That was his contemporary style, and then you know, you can already get the tendencies of actually that period that came after baroque and between the classical style. V: Gallant Style. A: Gallant Style, that his sons used when composing and creating compositions. So basically Bach observed all those tendencies and used them in his compositions. V: I would say today, if you want to be original, you have to combine several sources, sources of inspiration, not one. A: Yes, because so, so many things are already written and composed and sent, so you probably just have to mix things together. V: Exactly. Take one realistic approach from one composer that you like, another from a another school, right? Maybe if you like polyphonic you can keep that but add special specific modal writing style that you like from the later schools, right? Something that is rarely combined, and that will make your music more unique. A: Yes, it’s like Paul Hindemith created Ludus Tonalis, and of course I think, the inspiration for him to compose probably was from Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier. V: Yes. A: Or like Shostakovich also played relative too. But still we have to have our own unique style, but of course we know that they studied Bach too, so that’s the way how things should be done. V: I think our final word of advice besides articulating early style of music whether written or improvised today, should be, I think, be very open minded and look broadly at your influences, right? And then you can mix things up, creating different order. And you don’t know what will come out. Maybe the result will not be something you like. Maybe that will be another level of training that you do. But maybe the next step will lead to something with more interest, right Ausra? A: Yes, because I think you need to mix the elements of early and modern even if you are creating in that early style. Because if you would just create in that early style it would be like copying that style, and if you will not add anything new, then, I don’t know if it is worth doing. What do you think? V: In music, musical world today, there isn’t much success with this, I think. I think only in improvisation, yes, but if it’s written piece, people will not be too impressed if you just imitate somebody’s style, right? That’s in music, but let’s say in art, in art visual art, if you imitate style of dutch Renaissance or Baroque or something, if you can do this, people somehow will be very impressed and could pay a lot of money for just observing the pictures or photos of your paintings today. That’s a very weird situation, right, to create something old fashioned and people will be very happy. Because, you see, people like to look at stuff they could recognize, right? A: Yes, that’s true. The things that are familiar to them. V: That’s why people keep drawing pictures of Superman and Batman and other superheroes, right, characters. They are not inventing their own. Sometimes they do, but not always. They recreate them from the past movies, let’s say, or stories. Because their audience loves to look at stuff or read stuff that is familiar, right? A: Yes, that’s true. V: That’s why we keep playing masterpieces of 17th, 18th and 19th century in the concerts of organ music, right? Instead of constantly creating something original in 21st Century style. Right, Ausra? A: Yes, that’s right. V: We do sometimes create and incorporate but not always. There are people who do exclusively unique stuff, but they are, I think, in the minority. A: Mmm, hmm, that’s true. I think it’s hard to be always original. V: Yes. So with that optimistic note, we could end this discussion, and we hope to get more of your questions and feedback. Please send us. We love helping you grow as an organist in various spheres in organ playing. Thank you guys. This was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: And remember, when you practice… A: Miracles happen! Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. Vidas: Let start episode 157 of Ask Vidas and Ausra podcast. This question was sent in by Marco and he writes: Hi Vidas, I'm an organ student. I'm trying your method of subdividing a piece in fragments and voices and it's very helpful. My problem is that I find the practice quite stressful mainly for the following reasons: 1. There are sometime fragments that I cannot play correctly no matter how many times I repeat it. 2. I easily become anxious when I repeat a fragment, especially for the third time, because if I make a mistake I have to start again and repeat it at least three more times. Do you have any suggestion to make the process less tiresome? Thank you, Marco V: Do you think Ausra that people should be so severe when they practice a piece of music? A: I don’t think so you can hurt your nerve system if you will be always anxious and be so stressful about your practice. V: Almost you can feel that a person feels a guilt right, about making a mistake and feeling bad about himself or theirself that this mistake was made. Actually there is a saying that the person who makes the most mistakes will win actually in the long run. The person who fails the most will win. Do you know why Ausra? A: Why? V: Because they will try it many more times than the other person. A: That’s true. And to know I just thought about, you know, him saying that sometimes he makes mistakes and you know he cannot not sort of correct them and then he gets frustrated because he knows that has to repeat that part at least three more times and I’m thinking you know if there is certain spots that are possible for you to play correctly it means that you are doing something wrong in that spot and I would suggest for you to revise those fragments. Maybe, you know, you are playing them too fast. V: Or, you are making the texture too thick. A: Sure, maybe you are using a wrong finger because something is probably not right in those spots. Or, maybe you are just too anxious to get a good result. Things like this take time and it’s normal. V: Remember in our school there are a lot of students banging the piano as fast as they can in short fragments repeatedly over and over again like ten or twenty or fifty times. A: And it’s funny but they are repeating the same mistakes all over. Over and over again. V: Do you know what insanity is? The definition of insanity? A: No, I don’t know. V: Alfred Einstein said that “Insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results.” The definition of insanity. A: No. V: So, simply you have to change something in order to expect different result. And I’m not meaning Marco or any of our students in this way. I’m just illustrating how extreme this approach can become, right, if you play too fast or the the texture is too thick. For example, if you’re not ready to play without mistakes that fragment, maybe you could play just one line, one voice. A: Sure, but you have to know to do something about it. V: Change. A: About that, yes. V: You make a mistake and you are not satisfied with that mistake. That’s OK even though you are feeling angry or frustrated with yourself is not the best feeling but OK for now let’s say that you are angry. You accept that. You admit that you are angry and then you think “What can I change about the situation or about my feeling of the situation.” Right. If I cannot change the situation why should I become angry. Right. If I can’t change the situation then maybe I become less angry about that. A: Yes and no, if some particular spot give you so much trouble maybe just let it to rest for a while. Maybe you know, stop practicing that piece for a day and come back to it later, you know next day. Or, do a break of two days, because sometimes you know, you need to give for things time to rest and then you will go back to them and things will work well. I’ve had this experience many times, have you had it too? V: Obviously, yes. Of course what happens at the time when you rest, your mind is bombarded with another set of information and your old influences and inputs, informational inputs are no longer the current ones and you maybe tend to forget what happened bad in your past, right? And when you come back to the old spot when you made mistakes your fingers might feel like their at a fresh spot and forget that this was a difficult spot. A: Yes. V: So, maybe a week or so of playing something else would be beneficial and then coming back to the old spot. Ausra, do you make a lot of mistakes yourself when you practice? Do you allow yourself to make mistakes when you practice? A: Actually, no because the more mistakes I will make during my practice, the harder it will get to correct them. V: Exactly. So, you are doing something different that a lot of people, right? You are not allowing yourself to make those frequent mistakes. A: That’s right, so you just have to be really focused when you are practicing. V: Even at this level, right, very far advanced level we could play a piece, a familiar organ piece and make many mistakes if we are not careful, if we are playing too fast, if were playing it with the wrong fingering. You could do that, but we don’t allow ourselves. For example this morning I recorded my sight reading of BWV 552, the E-flat Major Prelude and Fugue by Bach which will later be used for transcription purposes of fingering and pedaling from the new score. So, I had to play almost cleanly and without mistakes so that people who will help to transcribe this score will understand what I’m doing, right, and the choices that I’m making with fingering would be more or less correct. Of course, I can edit them later in the first draft of the transcription. But, I tend to use more or less logical fingering, right? A: Yes. V: So how do you do that, Ausra, at the early stages of development, if a person doesn’t have advanced skill of playing difficult and advanced organ music. A: I think the most important thing at least for me is to know to practice with my actually mind first. That no if I have no sort of fresh head when I can practice. If I feel tired that I cannot understand what I am doing I stop practicing because I just don’t like that purely mechanical playing. V: So it’s a complex phenomenon. You have to understand how the pieces put together. In order to do that you have to have a good grasp of music theory and harmony and musical analysis and form. Right? So you think what the composer thought when he or she created this piece. Moreover, you have to have your own experience at creating music in the moment like improvisation or in a written form like composition or in the perfect scenario, both. Right? That would be the ideal situation. Of course, so my advice for all the people who are listening to this would be to have a complex education and expanding your entire musical horizons not only organ playing from score but many supplemental things. A: Yes, and always listen to what you are doing. That’s important too. Because so many people are just playing whatever, fast and loud. V: Do not worry about how fast or how slow you will achieve that results. Do not worry how much there is still to learn, right? And how many years it will take to perfect your art. It doesn’t matter at all. What matters is that you perfect your art just one percent a day. One percent. And every seventy-two days this percentage will double and at the end of a year you will perfect your art, your complex organ art. Not only organ playing or sight-reading skill, but everything together put together. You’ll perfect it thirty-eight hundred percent if you do that every day. That’s all. That’s enough. OK. So I think that this is the best we can hope to inspire you today. Go ahead and practice and don’t be frustrated with your mistakes. Or, even better, play as slowly or as transparently that you will not make those mistakes at all. A: True. V: Thank you. We hope this was useful. Please send us more of your questions. We love helping you grow. An remember, when you practice… A: Miracles happen.

Vidas: Let’s start Episode 66 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. And this question was sent by William. And he writes, “My question is I started working on the first sonata of Mendelssohn. How is it to be articulated. Detached or legato? The fast passages are very difficult to keep smooth at tempo. Also who has ideas on how to register this opening movement. I am working from score from 1920's. I think there has to be some thought on playing these great works of Mendelssohn!"

Hmm, interesting question! Have you played a few pieces by Mendelssohn, Ausra? Ausra: Yes, I definitely have. Vidas: Me too. So, I think we can talk about articulation first, and then about registration: general ideas about articulation, about registering Mendelssohn’s pieces; because remember, he wrote that preface. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: Great. So, articulation: Do you think that in the mid-19th century, when Mendelssohn created these pieces, articulate legato was already out of fashion, or…? Ausra: I think it was getting definitely out of fashion, and I think that legato was the main way to articulate music--to play music. Vidas: So, yeah, of course, in different places, you would discover some remnants of Baroque articulation, for sure, even in those places; because in even village organs, instruments would have mechanical action and Baroque specification--they would still be tuned in meantone sometimes, right? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: Meantone temperament. Remember, we recently heard Professor Pieter van Dijk from the Netherlands, play a piece by Romantic Dutch composer Jan Alber van Eycken--who was actually a student of Mendelssohn-- Ausra: Yes. Vidas: --And sometimes he articulated this piece with articulate legato. Ausra: Yes, that’s true, but still, you know, the main way to play it is legato. You use that “articulate legato” or you know, non legato only to emphasize the structure of a piece, when the score advises it. Vidas: So...all the notes should be slurred, except in certain places, right? Ausra: Yes, like repeated notes, of course you have to shorten them. Vidas: And staccato notes? Ausra: Yes. And ends of phrases, and the beginning of a new phrase, you have to take a break, to show the structure. Vidas: Or unison voices, when one voice overlaps with another and makes a unison interval, like C in one voice and C in another voice; you have to shorten the previous note also, so that it would be possible to hear that two voices sounding and not one. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: And there is an exact amount of rest you have to make, right? In these cases? Ausra: Yes. Usually you have to shorten it by half of its value. Vidas: So if the note is an 8th note value, so you make it a 16th note, and 16th note rests. Ausra: Yes. And it’s fairly hard, especially if you have, for example, more than one voice in one hand; and you have to keep one voice smoothly legato, and another voice detached; so that’s a challenge. You have to make sure you play with the right finger; and, of course, you have to use a lot of finger substitution. That’s the way to do it. It takes time. It’s a really hard thing to do. Vidas: And then, if you have, for example, triple meter, when the notes don’t divide exactly in half--so then it’s kind of tricky, right? You have to calculate what’s the unit value--what’s the most common, fastest rhythmical value in this piece, right? Maybe 16th note, maybe 8th note if it’s a slower piece. So then, it means that you should make a rest between repeated notes, between staccato notes, with the exact rest that unit value has. In this case, 16th note, or 8th note. So that would be very precise articulation. And your playing would be much, much clearer, this way. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: So Ausra, now let’s talk about registration. Mendelssohn himself wrote the preface for the six sonatas, and he wrote registration suggestions, right? First of all, do you remember, those pieces should be played with 16’ in the pedal, or not? Ausra: Yes, they have to have 16’... Vidas: Always, except when composers notate differently, right? Ausra: Yes, so always use 16’, except when, you know, it’s written in the score not to do it. Vidas: Then, Mendelssohn gradually explains the dynamic signs: pianissimo, piano, mezzoforte, forte, and fortissimo, I believe. Ausra: So basically five levels. Vidas: Five levels, yes. You can add a couple more, like mezzopiano, if you want; but the general feeling would be the same. So, what is pianissimo? In Mendelssohn’s terms, it would be very very simple, right? Just the softest stop on the organ. Ausra: Yes. Probably 8’ flute. Vidas: Or a string. Ausra: Or a string, yes. Strings became, I think, more and more common in those days. Vidas: Then piano would be a couple of those soft stops, combined. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: Then he goes to mezzoforte, right? So...But we could talk about mezzopiano. Mezzopiano probably would mean, maybe, combined few soft stops but not only at the 8’ level but… Ausra: At the 4’ level. Vidas: At the 4’ level, too. What else? In mezzoforte, can you engage already some of the louder stops? Maybe principals... Ausra: I think yes, you could try; it depends on your organ, but yes, you could definitely try. Vidas: Forte for Mendelssohn means full organ without some of the loudest stops. Basically, this means without reeds? Ausra: I would say so, yes. Vidas: Without strong reeds. Ausra: Because you already have to use mixtures, I guess, for forte; but not reeds. Vidas: And fortissimo means simply, full organ with reeds. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: And with couplers, if you want to. So that’s the basic idea, how to register Mendelssohn; but not only Mendelssohn, right? Ausra: Yes, you can do, I think, the same in Liszt pieces. Schumann probably. Vidas: To some extent, Brahms. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: Maybe even Reger, right? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: Maybe even Reger. Although, Reger requires a special pedal, Walze they call it, like Rollschweller. It’s like a crescendo pedal, basically. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: You gradually add stops by moving this pedal. That’s a later idea than mechanical action organs that Mendelssohn and Liszt played, right? We talk about, basically, Ladegast organs which were built in the mid-19th century; and maybe, to some extent, the earliest Walker organs, too. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: Excellent. So guys, please try to adapt those ideas into your situation. Maybe your organ that you have available, it will be different, you have to make compromises; but the general idea will be the same. Thanks guys, we hope this was useful to you. And please send us more of your questions; we love helping you grow as an organist. And...this was Vidas. Ausra: And Ausra. Vidas: And remember, when you practice… Ausra: Miracles happen.

Vidas: Let’s start Episode 65 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. And today’s question was sent by Patti, and she writes, “Dear Vidas and Ausra, here is a question that you might be interested in addressing in your podcast. It is about learning to cope with differences in resonance and delay when you play the organ.

The church where I normally play has a very “flat” acoustic -- no resonance -- and the organ sounds immediately, with no delay. So when I play a note, I immediately hear that note, and that’s what I’m used to. If I try to play somewhere that has a quite noticeable delay, or a lot of echo, I can manage simple or medium-difficult pieces, but if I try to play something that requires difficult coordination (a Bach fugue with a very active pedal part, for example) the delayed feedback is confusing and I can’t keep myself in sync. How do you manage this? Do you play more slowly, or more detached? Is there a way to learn not to listen to yourself, for example by practicing silently? Thanks for any tips on this, and thanks for all your advice and encouragement to us organ students, best wishes, Patti.” So Ausra, this is a question about, basically, adjusting to different acoustics. Ausra: Yes, that’s right. Vidas: Do you remember the time when we were students at the Lithuanian Academy of Music--we were just starting playing the organ--and of course, all the practice organs and even the studio organ were in rooms with dead acoustics? Ausra: Sure, yes. Vidas: So we were used to that setting. And then, it happened that somebody took us to a church. With lively acoustics. Do you remember the first church organ that you played? Ausra: Well, yes, and actually it’s interesting because it was the Casparini organ from 1776 at the Holy Ghost church here in Vilnius, and I played the C minor Prelude and Fugue, BWV 546 by J. S. Bach. I was just so fascinated with that organ; but, you know, at that time I didn’t even think about acoustics and all those sort of things, because it was so fascinating. But I could tell you about the time when I played in the northern part of Lithuania in Biržai when I was still a student; and that organ was a pneumatic organ, sort of Romantic style, like late 19th century, early 20th century organ; and simply, I could not manage playing it, because the sound was so delayed no matter what I did. And instead of just letting organ sound, to let it go, I was pushing harder and harder; and the more I was trying to control that organ, the more delayed it sounded! It was so frustrating! But when I came back to the same instrument many years later, I found no difficulty to play it. So to make a long story short, the more you try different instruments in various settings, the easier it will get. What do you think about it? Vidas: Good story, I believe I played in Biržai too--I think maybe not on that occasion--but yes, if you listen to what you basically hear in the room, your playing starts to be slower and slower and slower. But if you try to mechanically play with your fingers and your feet, just like it would be in a normal setting, and disconnect your ears a little bit from the echos --then it’s normal. But of course, as a beginner it’s extremely difficult to do this. Ausra: But as Patti mentioned in her question, it’s very true what she mentioned: that if you’re playing in large acoustics, then definitely you have to articulate more. Especially when playing Bach, or any kind of polyphonic music. Because that will give you better sound; and of course, you might want to slow down just a little bit, in large acoustics. Vidas: Yeah, we usually slow down and articulate more. Make larger spaces between the notes when you play in large settings with huge reverberations. For example, at our church, St. John’s Church, at night when I play the full organ, then it is very very quiet in the church, and outside the church too; so the reverberation increases up to maybe 5, 6, or even 7 seconds, especially when the room is empty. So it’s a lot of difference, very different feeling, playing during the day--or playing during a concert, when the room is packed! Ausra: Sure, then the acoustics just disappear--not entirely, but a little bit, yes. Vidas: So we always listen to what is happening downstairs with our sound. We listen to the echo: not what we are playing right here, but what the listener is actually hearing. Ausra: Yes, and when you are playing in large acoustics, you always have to keep in mind phrasing: the end of sentences; never jump on to the next one, because it will sound bad. Just listen to the end of the sound. Vidas: You mean those places where the musical idea ends, and another musical idea begins-- Ausra: Yes, definitely! Vidas: You have to breathe, take a rest, and wait for the reverberation--wait for an echo a little bit. A little bit. Not too much, probably, if it’s just a mid-piece section. Ausra: Yes. But still you have to take a breath. And when playing on a mechanical organ, it works nicely if you register it yourself, and you change stops during performance, yourself; because it also gives you correct timing. And it works well, because if you have to move your hand and to add or delete a stop, it will give quite a good amount of time, and it works nicely, acoustically. Vidas: And even on electropneumatical organ with combinations, you can pretend that you are pushing the stops yourself by hand; imagine that you are not pressing the pistons, but you are moving the stop knobs yourself; and that way, you will make larger breaks between sections. Ausra: And you need to think about these things in advance, not just when you will go to an actual instrument. For example, if you have settings, when you are learning a piece on the classroom organ with dead acoustics (or at your home church with no acoustics), but you know that you will have to perform it, on a different kind of instrument with larger acoustics. You need to pretend that you have that acoustic already. You need to think about things in advance. Because, it will not be so easy, especially for a beginner to change, for example, articulation; so maybe just practice with a shorter touch before going to that actual instrument. Vidas: Good idea. Prepare in advance in your practice room. And of course, don’t despair if you don’t get it right the first time, second time, fifth time, or even the tenth time. When, Ausra, did you discover, yourself, that it’s easier for you on a big acoustics? Ausra: Well, it took quite a while. I think it took a few years, at least. Vidas: A few years of many performances! Ausra: Yes, many performances. Vidas: Maybe think this way: every tenth performance you will discover something new about that acoustic, about this instrument, about yourself. And it will be like a small breakthrough for you. Ausra: Yes, but I guarantee, when you will play many times with large acoustics, it will be much harder for you to play with dead acoustics. When you can actually hear every little thing, that you even would not have noticed on the large organ and big acoustics. Vidas: Yeah, it’s very slippery to play in dead acoustics! Everything is visible, and you’re sort of naked! Ausra: I know, if now I would have to play at the Academy of Music in that room where we played all our exams...I would probably just die! Vidas: Okay, guys, we hope this was useful to you. Please send us more of your questions, we love helping you grow as an organist. And you can do this by subscribing to our blog at www.organduo.lt if you haven’t done so already, and simply replying to any of our messages that you get. Thanks guys, this was Vidas. Ausra: And Ausra. Vidas: And remember, when you practice… Ausra: Miracles happen.

Today's question was posted by Paul:

" ICH RUF ZU DIR, HERR JESU CHRIST - When you play this, it is very musical (the most musical I've ever heard) but I've heard this played very mechanical in most recordings. How do you know when to speed up and slow down in this piece (or any other Bach piece) to make it musical? Is there a formula? I love this new series of yours (except sometimes it's difficult to hear you in the car). Thank you for all your help! You two are inspiring!" What Paul is referring to here is agogic. It's the principle that let's you to fluctuate the tempo very gently. Basically, we slow down when something new or interesting is happening - key change, new section, new theme etc. Then we can pick up the tempo slightly. Listen to the full answer at #AskVidasAndAusra If you want us to answer your questions, post them as comments to this post and use a hashtag #AskVidasAndAusra so that we would be able to find them. And remember... When you practice, miracles happen. Vidas and Ausra (Get free updates of new posts here) TRANSCRIPT Vidas: Hello guys, this is Vidas. Ausra: And Ausra. Vidas: Welcome to episode number 8 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. This question was posted by Paul. He writes about the piece “Ich ruf zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ” by Johann Sebastian Bach from the Orgelbuchlein. He writes, "When you play this it is very musical, the most musical I've ever heard, but I've heard this played very mechanical in most recordings. How do you know when to speed up and slow down in this piece, or any other Bach piece, to make it musical? Is there a formula? I love this new series of yours, except sometimes it is difficult to hear you in the car. Thank you for all your help. You two are inspiring". Interesting, right? What do you think, Ausra? Ausra: It's a very hard question. Definitely there can not be one formula for every piece and, in fact, I would not say that you have to slow down or speed up in some places. What do you think about it? Vidas: I think Paul is referring to a technique called agogic. It's a principle that lets you fluctuate the tempo very gently. You have to keep in mind the structure of the piece and then you can slow down when something new or interesting is happening. For example, key change, new section, new theme, things like that. After that you can pick up the tempo very slightly. Ausra: Yes, but everything must be very gentle. Vidas: Gentle and probably very slight, right? Not too over-exaggerate. Ausra: Yes, because if you over-exaggerate it might sound comic. Vidas: Right. So I think what you have to keep in mind still, the basic pulse of the piece. Always keep counting in beats. Then if something interesting is happening and you observe it, and you have to always listen and follow the score very precisely. Follow the score not like performer but maybe like listener. Ausra: Sure. This is why it is good to know your piece throughout, how it's put together, to know its form, to know its harmony. This might help you to use your agogic right. For example, I would suggest not to lean more on the dissonances because they are so important. Maybe you can slow down a little bit in each cadence, because cadence is like the end of the musical thought. Sometimes it's a final thought at the end of the piece, sometimes it's just in the middle. Vidas: Does this refer only to Bach’s pieces or to everyone? Ausra: I think it refers to any other pieces as well. And by speeding up, I think this rule might be applied to sequences. Sequential motives. Vidas: You start slower, then you can speed up, and then slow down at the end. Ausra: But only a little bit, not too much. Vidas: It's sort of similar to reciting poetry. If you ever heard people recite poetry automatically. You know, automatically meaning they keep the rhythm: Tah TAH tah tah TAH tah tah TAH tah tah TAH, Tah TAH tah tah TAH tah tah TAH. Tah TAH tah tah TAH tah tah TAH tah tah TAH, Tah TAH tah tah TAH tah tah TAH. Very automatically. And it's boring. But the best, probably, speakers, make it sound very natural and spontaneous. Ausra: Sure. Vidas: So that's what we're talking about it music too. Ausra: I never think how to play musically, not to play it automatically. Also you must to overcome, all the technical difficulties first, and then just to focus on music itself. How to play it nice. Very musically. Vidas: So I hope this will explain and help Paul, and others who are trying to play pieces musically. Not automatically. And that's one of the main things you can do. Gentle, agogical fluctuations. If you want to send us your questions, feel free to do this by posting them as comments to this post, and make sure you use hashtag #AskVidasAndAusra so that we can find them. And if you want to get more advice and inspiration about organ playing, then make sure you subscribe to our blog at www.organduo.lt and you will get everything we post for free. Also deliver it in your email inbox. Wonderful. I hope this was useful, and see you next time. This was Vidas. Ausra: And Ausra. Vidas: And remember when you practice ... Ausra: Miracles happen.

We're so delighted to be able to start a new podcast #AskVidasAndAusra!

We'll do a limited number of short audio episodes and share them on this blog. Our goal here is to help our most valued subscribers, people who support the most what we do. Sometimes we'll answer questions together, sometimes separately. So today's question was sent by Jan who is taking advantage of the free trial of our Total Organist membership program. Here's what she wrote: "Dear Vidas and Ausra, My most pressing question is... how can I keep a steady tempo? My teacher tells me every time I have a lesson, in every piece that I play, that I am playing with multiple tempos. I think that I am playing with a steady beat but when I test with the metronome, I am all over the place. I am stuck as to how to fix this problem. At present I do some of my practice with a metronome. I am not a beginner. This is frustrating and disheartening. Thank you for your help." Listen to what we had to say this morning about it while doing our 10000 step practice in the woods. IMPORTANT: If you would like us to answer your questions for #AskVidasAndAusra and share on this blog, please post them as comments and not through email. Make sure you add a hashtag #AskVidasAndAusra because otherwise your question might get lost among many other comments people leave. With the hashtag #AskVidasAndAusra we'll know exactly you want us to answer them in the correct place. We are looking forward to helping you reach your dreams. Are you excited as much as we are? You should be. And remember... When you practice, miracles happen. Vidas and Ausra (Get free updates of new posts here) TRANSCRIPT Vidas: Hello guys. This is Vidas. Ausra: And Ausra. Vidas: And, this is episode number one of our new show, #AskVidasAndAusra. We're very excited and we're walking here though the woods now in the morning, and you can hear the birds singing, correct? How are you feeling today, Ausra? Ausra: I'm fine. What about you? Vidas: Yeah, I think I'm quite ready to answer people’s questions. We received four questions so far, and we have four episodes lined up for you. And, today we're going to basically answer the first question that came to us, and it was written by Jan, and it was wonderful question, I'm trying to read now. And, she writes things about playing with a steady tempo. Here is "How can I keep a steady tempo?" That's her question, and I will explain. She writes "My teacher tells me every time I have a lesson, in every piece that I play, that I am playing with multiple tempos. I think that I am playing with a steady beat but when I test with the metronome, I am all over the place. I am stuck as to how to fix this problem at present. I do some of my practice with a metronome." And, she writes that she's not a beginner and that's, of course, frustrating and disheartening. So, Ausra, do you think that this kind of problem is common among organists? Ausra: Yes, I think this problem is common among all musicians, not only organists, because even pianists or violinists can have the same problem. Vidas: That's true. Do you remember the time when you had this problem? Because, it was probably a very long time ago. Ausra: Yes, I remember one time, when I was working on Bach’s C Minor Prelude and Fugue. Vidas: BWV 546? Ausra: Yes, I had that problem in the prelude. Vidas: And, especially in that episode, when the eighth notes change with the triplets, right? Ausra: Yes, that's right. Vidas: So, what helped you that moment to solve this problem? Ausra: I don't remember exactly, but in general I thought a lot about it. Because then, later in life I returned to that piece. I just could not understand how I could play so badly at that time, so arhythmically. Vidas: Yeah and our professor, we were studying by the same professor Leopoldas Digrys, I think at the time. And, he was very mad, actually, because of this spat episode, and- Ausra: I think he just kept shouting at me and I think I was scared of him, that I could not play it correctly, so never shout at your students. Vidas: That's rule number one. Even if you are frustrated with your students, you should not shout at them, right? But, of course, back to the question. Imagine Jan is having the same thing like you had back, maybe some 20 years ago, when you first started playing the organ. Or, other people around the world, also facing the same problem. What do you think, Ausra, keeping the steady tempo might be possible if a person plays with the metronome all the time? Ausra: Actually, metronome is only to check your tempo, what tempo you should be. But, it's not a good tool to practice with it all the time, because finally when you will have to perform this piece, during exam or during a recital, you will not have a metronome. Metronome doesn't let you to show the structure of a piece, actually, because keeping the steady tempo is not the only thing you have to do in the piece. Because, there are other structural moments, cadences where you might have to slow down a little bit, or fasten up a little bit to show the structure of a piece. To play like a human being, not like a robot. And that’s, I think, why a metronome is not such a great idea to practice with it all the time. Maybe time after time, you can do it, but not all the time, and I don't think that metronome will solve this problem of playing in steady tempo. Vidas: Hey, do you remember we have in Unda Maris studio, this wonderful lady who is practicing with us for six years now I think, from the beginning. And, she has the goal to master all the eight little Preludes and Fugues, right? And, she has mastered, I think five or six of them by now. Just a couple of them left, right? And she is really determined, but one of her major problems is really keeping the steady tempo in pieces, right? So, remember what we suggested to her too? I think to count out loud and sub-divide the beats. If, imagine she plays the piece in 4/4 meter. I think we said counting out loud those four beats, four quarter notes, and doing this loudly, counting out loud. Because, as Jan probably experiences, because a lot of people think they are playing in a steady tempo, and even counting naturally and evenly. But, it appears that when they listen to the recording, it's not true, right? Or, when somebody else is listening from the side. The only possible way that I found, is really to force yourself to count out loud steadily. Would you agree, Ausra? Ausra: Yes, it's very helpful, but you have to do it loudly. Or, to do it mechanically with your mouth, with your tongue, just sub-divide. For example, sixteenths, feel them, because otherwise if you will do it only in your head, it doesn't happen. It will not work. Vidas: Right, because you think you are counting steadily inside of you, right? In your mind. But, your music can be all over the place. Ausra: That's what I did when I learned Icarus by Jean Guillou. I sub-divided all the time, the smallest values, with my tongue. It actually really helped, because it's a tricky piece to play it technically and to play it rhythmically correctly, in a very fast tempo. So, that's what I did to beginning of learning that piece. I would just sub-divide all the time, and even do it in my performance. At a final stage, sometimes I would sub-divide at least some spots. Just to keep it in good tempo and rhythmically, correctly. Vidas: So, then probably the shortcut to this, for Jan and others, to master the piece at the level that she could really play fluently, in order to concentrate on the counting, right? Ausra: Sure, because another problem why the tempo can change. It might be that ... Although, she is not a beginner, yes? At the keyboard, but still, all of us have some harder spots in the piece and some easier spots, and sometimes when you get to the harder spot, you start to slow down. But, when you know you are playing an easier place, let see, where the sequences are going all the time, you sort of starting to go faster and faster because it's easier. You really need to make sure that places where you slow down are not technically harder than other places. Vidas: Right. All of the episodes in your piece, in your mind, should be of equal level of complexity. Although, some episodes might have 16th notes, or even 32nd notes, or triplets, or syncopation, right? But, you have to master those episodes so well that they should be as easy as playing quarter notes, let's say, or half notes in other spots, right? So, wonderful. I think Jan can now try this technique, and other people can try this technique. By the way, Jan is our Total Organist student and really tries to perfect her organ playing through our study programs and coaching, training materials, which also a lot of people have found tremendously valuable. And, right now we have this 30 day trial period, where you can really subscribe for free and try out all the material without any payment for 30 days, for one month. And, if you like it, you can decide to keep subscribing and if you decide it's not for you, you can cancel before the month ends. So, I think we will go on with our day to day things right now. As we are walking through the woods, I think the birds are singing quite loud, and mosquitoes are biting in my legs now, because I'm wearing shorts and my feet are basically uncovered. And, it's a really beautiful view, very green, wonderful morning. Ausra, what piece will you be practicing today, by the way? Ausra: I think I finally will learn the Piece d'Orgue. Vidas: Piece d'Orgue, right? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: It's a fantastic piece. Do you need my fingerings that I am preparing for this? Ausra: I think it will be helpful. Vidas: And pedalings right? Ausra: Yes, especially nice that I don't have to write them down myself. Vidas: Right, right, because sometimes people don't like to write fingerings because it's a lot of work to do this, but if somebody can provide the fingerings and pedalings for you, that saves maybe 30 hours of work for some people, right? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: Wonderful. So guys, this was Vidas and Ausra talking to you from the woods of this vicinity of Vilnius, Lithuania. And, if you like this episode and would like to ask us more questions related to any area of organ playing, basically, we'd like to help you achieve your dreams. So, click on the comments section of this post and send us your question. But, makes sure we find this question, because a lot of comments we get is not related to our podcast, right? But, basically to anything else. So, if you want us to find and answer your questions directly on this #AskVidasAndAusra podcast, right? So, make sure you include hashtag, #AskVidasAndAusra and post it on the comment section of this blog. So, thank you so much, guys. This is Vidas. Ausra: And Ausra. Vidas: And, I hope you will have a tremendous success in your practice today. Ausra: Bye. By Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene (get free updates of new posts here)

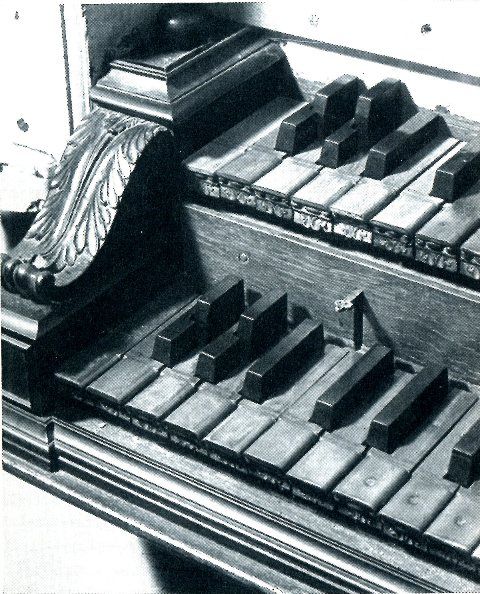

Vidas and I are preparing to perform in Sweden this summer. We will be playing an instrument from Sweelinck's time. It stands in Stockholm's German St Gertrude church (the Duben organ) and has all kinds of features of old organs: mean-tone temperament, split keys, high-pitched tuning, and short octave. A short octave in this case are the 3 diatonical keys in the bass octave - C, D, and E. This means music with C# and D# in this octave cannot be played. So we chose our repertoire very carefully, avoiding pieces with more than 1 accidental. But it's still a challenge to master the new layout of this type of keyboard. In the above picture you can see how a similar keyboard with CDE short octave looks like. It works this way: The lowest note which looks like E is actually C. D looks like F#. E looks like G#. F looks like F. Great! F# is the additional semitone on top of the 1st sharp. G is G. Great! G# is the additional semitone on top of the 2nd sharp. From A everything looks normal again. You might already feel that adjusting to this short octave will take some time and will require some special fingering. It takes more than that. We will be circling with pencil all our notes in the bass octave of our scores which would require re-positioning. And then we will be practicing on the modern organ or piano the way it would work on the old organ in Stockholm. The result will not be pleasant (when we need C, we'll play E; when we need D, we'll play F# etc.). But this is the only way to get used to the short octave on the target organ and shorten the time needed to adjust. By Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene (get free updates of new posts here)

One of the most common mistakes beginner organists make is to keep the uneven tempo in their pieces. Where it's easy, they speed up, where it's difficult, they slow down. No matter how hard they try to keep the steady tempo - it's just too overwhelming. Here's the trick which CONSTANTLY helps me to be precise in my playing: In rhythmically difficult places I keep counting and subdividing the beats down to the smallest rhythmical value of the piece. Let's say, you're playing BWV 554 and some places of this prelude and fugue in D minor are more difficult than others. What beginner organists often do, they slow down in the middle of the fugue where the pedal part comes in. They do this towards the end when the texture gets more complex. Since the smallest rhythmical unit here is the 16th notes I recommend counting in these note values. In your mind keep a steady flow of sixteenths. Then you won't have to worry about uneven tempo. By Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene (get free updates of new posts here)

One of the characteristics of organists who lack musical intuition is that they play only notes without giving any thought about what happened in the mind of the composer when they wrote it. Also they don't think about what any of the notes, passages or chords mean. And I don't mean to give negative criticism here. It's just that they lack certain training which can be improved over time. Usually such organists also tend to end their pieces abruptly. This is like driving your car and when you have finished your trip and arrived at the destination, you simply engage the emergency hand break and your car stops suddenly. The only time we do this is for emergencies, right? So why the ending of organ pieces should be any different? Sure, there are instances when you have to leave your listeners surprised at the end but in most cases they should feel the ending coming. So an obvious way to do it is to gently slow down at the end and hold the last note longer. You have to because as you slow down, you keep counting the beats slower and slower. Imagine, you're playing "Kommst Du nun Jesu vom Himmel herunter" from the 6 Schubler chorale preludes by J.S. Bach and you forget to slow down at the end of the final Ritornello and abruptly release the last note. It's like an accident, right? Instead, keep slowing down in your mind starting maybe a couple of beats in the penultimate measure and hold the last note longer. Do this and your piece will end very naturally. |

DON'T MISS A THING! FREE UPDATES BY EMAIL.Thank you!You have successfully joined our subscriber list.  Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas

Authors

Drs. Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene Organists of Vilnius University , creators of Secrets of Organ Playing. Our Hauptwerk Setup:

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

This site participates in the Amazon, Thomann and other affiliate programs, the proceeds of which keep it free for anyone to read.

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed