|

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas!

Ausra: And Ausra! V: Let’s start episode 512 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Alex, and he writes: “Hello Vidas, My dream as a long-time pianist/harpsichordist and new organist is to be an excellent performer of early music and hymnody. The three biggest obstacles: 1) Pedal technique 2) Lack of practice time due to graduate school (in choral conducting) 3) Physical limitations in my neck, back, and arms which keep me from being able to practice more than about 90 minutes per day. Thank you for receiving feedback. I absolutely love all the content on your wonderful website. God’s blessings on your excellent musical endeavors!” So, Ausra, Alex wants to be an excellent performer of early music and hymnody! A: Well, that’s a nice dream. V: But, so far, he lacks pedal technique, A: Which is natural, because he played piano and harpsichord before now, so he’s a new organist, so that’s natural. V: Two, lack of practice time, because he is in school, A: Well, I think we all need more practice time, and we all lack time in general. V: And then, he can’t practice for a longer period of time over 90 minutes. A: Well, since his dream is to become an excellent performer of only early music, I would say that 90 minutes is plenty of time to practice on a regular basis, if you play only organ. But of course, if you have to divide this 90 minutes between all three of these instruments that he has, it’s not enough. V: Piano, harpsichord, and organ. A: Yes. V: Out of these three obstacles, I think pedal technique is the least important. Don’t you think? A: Why do you think so? V: Because, if you keep practicing, you will advance in your pedal technique with time. A: True, if you will practice, which is the most important thing. V: And, the physical limitation in his body prevents him from practicing for a longer period, but as you say, it’s quite enough for early music to practice that much, with breaks, probably, too. A: Yes! And, you know, if you have some sort of physical limitations, it means that you need to find time some how to improve your body’s state. V: Yes. A: And maybe to strengthen your muscles, which, in the long term, would allow you to practice for longer periods of time. V: Why do you think people lack practice time while they are in school? Because being in school is one of the best times in life, I would think. A: Well, I don’t know what his position is, what else he does, if he only studies, or he has a part time job somewhere, or he works on campus, so it’s hard to tell, but yes, I remember my study years, and I haven’t practiced so much now as I had during my studies. V: Me, too, because when you graduate, all kinds of life things get in the way, and not only things, but problems, challenges… you have to think about feeding yourself and your family, perhaps, so you have to find a stream of revenue—preferably several—in order to feel secure, and this occupies a lot of brain space. A lot of thinking goes into this, and a lot of energy. A: So, I guess while being a student is an excellent opportunity to build up good organ technique. You will appreciate it later. V: Yes, whatever you build up right now will become the foundation for you later on. Can you advance after school? A: Yes, you can, but you will need to double your efforts to achieve that. V: Because school is designed to help people stay motivated and keep on track with deadlines and due dates and exams. Basically, all the thinking is done for you—all the curriculum—so you just have to follow the path. It’s not the most realistic path, of course, in life. When you graduate, you become sort of on your own. You no longer have the support of professors and other students. You might have support, but you have to seek it out actively in other ways. A: And the worse thing is that so many people nowadays work in something else, not in the field of expertise. V: Yes. So their profession becomes like a hobby to them. A: I know! Like for example, how my parents hired one man who did some work at their house V: With metal? A: With metal, yes. And he actually graduated...his major is architecture. But he doesn’t do anything like that, because he wasn’t able to find a job according to his profession. I hear many cases like his. V: Right. I think just yesterday, I was in my church in the morning, preparing to record a sample with experiments in organ sound, how two Timpani pipes sound, and how the organ sound is disappearing when you turn off the organ blower while still holding the chord. We were doing this together with one artist from the art academy—it’s part of our collaboration between the university and the art academy—and I asked her, she’s an instructor at the art academy, and I asked her, “What about other students at the academy? Are they building their portfolios while they are still in school, or are they waiting to get their diploma?” What I’m referring to is, of course, if they are putting their work online, where people can find them, therefore their reputation would grow over time if they kept posting and uploading. You know what I mean, right Ausra? A: Yes. V: And it appears that this instructor, this artist, says that most of them are waiting! Just maybe 1% of them are doing something with their work, and putting them online, outside of what is required. You know? A: They are waiting for a miracle after studies. I remember when we came back from the United States and wrote to our professors, Quentin Faulkner and George Ritchie, that we only received a position teaching at Čiurlionis National School of Arts in the Music Theory department, that Quentin Faulkner wrote us back that it would be a dream job for most Americans who graduated from the university in Fine and Performing Arts, and at that moment, I thought, “Wow, I have a Doctoral Degree in Organ Performance, and I have to satisfy myself with teaching basically in the arts school, which is not even at the university level, it’s more like at the high school level, a specialized school. But now, after teaching there for 14 years, I understand what he meant. And seeing life around myself and meeting other people who work doing, let’s say, not what they have studied, I feel that I’m really lucky. V: Me, too. Even though I no longer teach at school. Maybe that’s why I’m lucky. Alright guys, please send us more of your questions; we love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice, A: Miracles happen.

Comments

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 341, of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Bruce. And he writes: Hi Vidas, I just came across your youtube of Estampie Retrove from the Robertsbridge Codex. Do you have sheet music to this? Preferably not in tablature; actually, regular manuscript and tablature would be fun. Cheers, -Bruce V: Have you seen my prepared score of Estampie Retrove? A: I have played from it, performed from it in the recital. Yes, I have seen it. V: Mmm-hmm. Let’s open our Secrets Of Organ Playing store, and search for Estampie and we have two Estampies—one is Estampie Retrove, and second is Estampie, but a different version. So, Estampie Retrove is the oldest surviving organ piece. It’s from Robertsbridge Codex, which was compiled in the 14th Century, approximately in 1360, from the time of Boccacio and Decameron. This music is of Italian origin but preserved in the British library. It’s a piece only for manuals, because at that time, of course, organs mostly didn’t have any pedals. A: True. It was just the beginning of development of that instrument. And in general of instrumental music. V: Mmm-hmm. A: Because vocal music always came first. V: I’ve heard this piece performed by an early music ensemble—medieval ensemble in Vilnius during an early music festival Banchetto Musicale and they played it not on the organ, but on two instruments—organetto and some kind of string viol, the lower instrument, was a viol, and it played the lower part, and the other instrument was oganetto, like a Portative organ, very small, maybe two octaves wide of range, and it could be only played with one hand. A: How did it sound? Do you liked it? V: Yes. And I observed the keyboard. The keys were so small and tiny. You could not easily play it without experience, I think. I was fascinated. It was just before I had the score prepared. I knew this piece for a long time, but didn’t have fingering prepared. So the reason I prepared fingering was because, remember we needed some pieces from 14th Century in our organ demonstrations—‘Meet the King of Instruments’. A: I remember it, yes. V: And it seemed like a very good example. So then I notated the fingering and the part of our subscribers and students already were playing from it. So, if Bruce is interested, of course we can put a link in the written description, or if you are listening to the podcast, you could go to our Secrets of OrganPlaying store, on Shopify. The way to find it, it’s just to go to organduo.lt and click on Store. And then you will be taken to our Secrets of Organ Playing Store and you could search in the search bar for this, for the sheet music. A: I remember it was fun to play this Estampie Retrove because usually I teach harmony on a daily basis, and I always preach that you shouldn’t be using that parallel fifths while harmonizing melody. And here I am harmony teacher playing all the solo piece, which is written entirely with parallel fifths. It was fun. V: It would be a good dictation for students. A: I enjoyed it very much. V: Have you ever played for your kids this piece? A: Sometimes, I just play like couple measures of it. V: Mmm-mmm. Me too. And they react very strangely—what is that, right? I think I played a dictation like maybe eight measures or ten or twelve measures out of it. Let’s see—one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine measures until the first stop. But it was so uncommon for them. They didn’t know what to write, right? Because this music is so old, older than the oldest trees in Lithuania. A: True. V: What’s the oldest tree in Lithuania? A: I don’t think, maybe that Stelmužės ąžuolas or Stelmužė oak. V: Oak, mmm-hmm. Is it from 15th Century or 16th Century? A: It’s very, very old. V: Older than this? A: True. V: Seven hundred years old? A: I’m not sure. I have to check it. V: Let’s check it right now. Stelmužės ąžuolas. Oh, this is the oldest and the thickest… A: Tree. V: Tree in Lithuania. One of the oldest oak tress in Europe. The oak is around 1500 years old. 1500 years! A: Wow! V: It’s diameter is 3.5 meters, and 13 meters around the, next to the ground. Eight or nine grown up men have to go around this tree to reach, with hands. I wonder how many piglets and hedgehogs would you need. A: Way too many, probably. V: So that’s oak from maybe 6th Century or 5th Century. Nobody can tell for sure, right? But we didn’t have organ music from that time. A: So, 1-0 - trees rule. Trees win against the organ. V: Wonderful. Thank you guys for sending these questions. It’s so fascinating to sometimes dig up all the facts that we have forgotten and share it with you here. A: Yes, it’s very nice. V: And you hope, we hope you will enjoy playing Estampie Retrove. And actually I was surprised, because this is one of my more popular videos. Let’s check on Youtube, how many views does it have. Estampie. A: When I was practicing this piece, getting ready for recital, I though ‘oh, it’s so easy. It’s not worth for practicing much’. But actually it’s not true. You need to put some work onto it. And after playing it for some times—because it keeps repeating itself—it affects you as some sort of meditation. V: Mmm-hmm. A: So it’s really worthwhile trying it. V: The earliest organ music Estampie Retrove video, it was viewed 7004 times. A: Still, I don’t think it’s a record. I remember us watching that movie, with Bradley Cooper and Lady Gaga. And even like after that movie was shown for like three weeks, that one of the songs from that movie already had what like, millions and millions of views. So… V: Do you know, that maybe I should do another podcast conversation with my top Youtube videos—a list of top ten. Not now, but maybe in the future because I’ve just opened Youtube channel and the list is interesting. Okay, in the future we’ll share it and discuss. Thank you guys. This was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: And remember, when you practice... A: Miracles happen! By Vidas Pinkevicius (get free updates of new posts here)

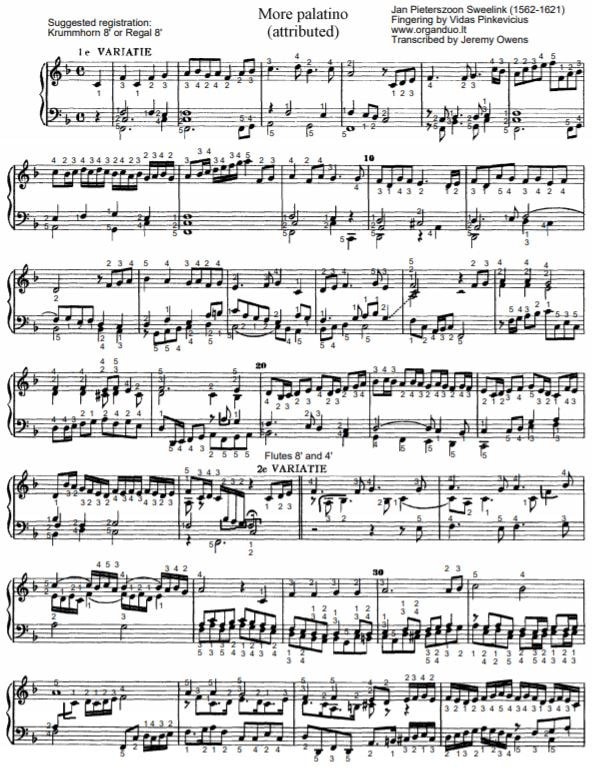

Yesterday I went to our church to practice 4 pieces from Buxheimer Organ Book. This is the German music collection written in the middle of the 15th century, approximately when Christopher Columbus was born, 600 years ago. The pieces in my edition where written in 3 staves but the lowest stave wasn't supposed to be played with pedals. I had to play the two lowest parts with the left hand. The problem is that in the 15th century, it was quite common for voices to cross each other which means that the lowest part can go higher than the middle part. It makes reading such a score quite a burden. What helped me was to slow down my practice tempo significantly and play the resulting three-note chords one by one, almost without the rhythm. In other words, I had to make sure I don't press the next notes without being 100 % certain the notes will be correct. It's only possible in extremely slow tempo. See if this helps you, if you ever have to play music with voice crossing. These 4 delightful variations of More Palatino originally were attributed to Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck.

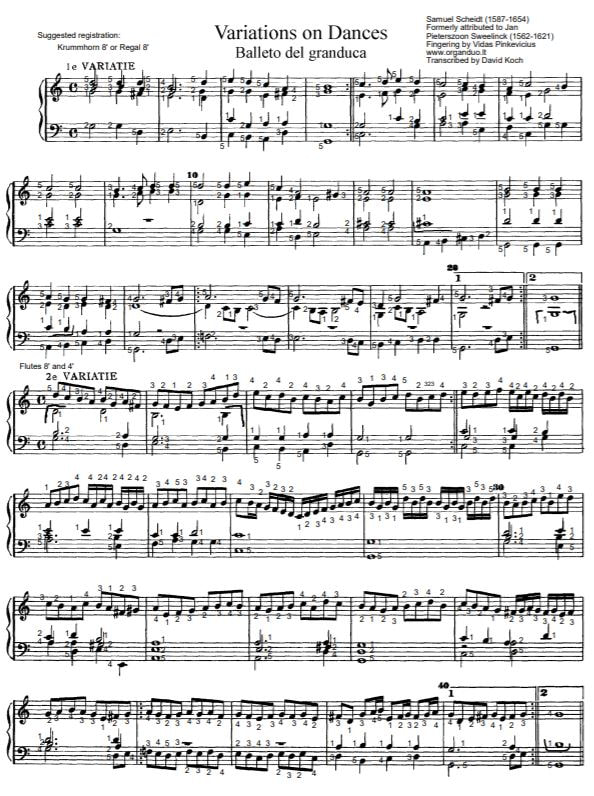

I have created this score with the hope that it will help my students who love early music to recreate articulate legato style automatically, almost without thinking. Thanks to Jeremy Owens for his meticulous transcription of fingering from the slow motion videos. If you liked Baletto del Granduca, I'm sure you'll love More Palatino too. Check it out here Intermediate level. Manuals only. PDF score. 3 pages. 50% discount is valid until March 16. This score is free for Total Organist students. These delightful variations of Balleto del Granduca originally were attributed to Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck but recent scholarship points to Samuel Scheidt as a composer.

I have created this score with the hope that it will help my students who love early music to recreate articulate legato style automatically, almost without thinking. Thanks to David Koch for his meticulous transcription of fingering from the slow motion videos. Intermediate level. Manuals only. PDF score. 3 pages. Check it out here 50% discount is valid until February 8. This score is free for Total Organist students.

Vidas: Let’s start Episode 109 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. Today’s question was sent by Barbara, and she writes:

Dear Vidas and Ausra, You are very welcome. Your emails have already answered many questions -- some I didn't even know I had -- everything from why some of your fingerings are so different to how to hear inner voices to how to deal with injuries. Thank you! And thank you very much for the Boellmann toccata. I actually learned it many years ago when I was still taking organ lessons (I started lessons 18 years ago at age 48). I played it for a Halloween postlude one year at my church, and they brought the Sunday school in to listen, so I really pulled out all the stops at the end. But I'm very glad to have your fingering. I've been on retirement "vacation" for many months because of numbness in my hands, so I've been trying new fingerings as I ease back into things (long story, but I think I've been using too much piano technique on the organ all these years and it's taken its toll, especially as my muscles and joints age). Thinking of a question for you is a little like having to choose one wish for a fairy godmother. But here goes. One of my current struggles is being a better listener at concerts and recitals where the music is unfamiliar. I've learned a lot about baroque/classical/romantic music, but I don't know how to fully appreciate early music, especially music written before tempering. Do you have any suggestions for how to approach this? Recommendations for good listening collections of music using specific modes or styles? I this will also help me to better appreciate organ improvisations and modern music. Many, many thanks again for all you do. Best wishes to you both, Barbara What do you think, Ausra? Ausra: Very nice letter. And a very interesting question, actually. Well you know, in order to be better able to understand early music, you would probably need to listen to some recordings of this music performed on original instruments, on historical instruments. Because this makes all the difference in the world. On the modern instruments, performing early music doesn’t sound good enough--or not as good as it should sound on the original instruments. What do you think about that, Vidas? Vidas: With a few exceptions. If music is more familiar to modern ears--let’s say the style is more familiar, like one of Johann Sebastian Bach’s--then it sounds good on almost any type of instrument, right? Ausra: Yes, that’s true. But I’m talking about even earlier music. Vidas: Mhm. Ausra: Like Robertsbridge Codex and that kind of music. Vidas: Yes, we have to understand here that people who wrote similar pieces 700 years ago were living in times that the mentality was closer to pagans in the ages before Christ than to our modern days. Because they were basically completely, as they say, world-conscious; they believed in higher powers. And today’s people still do believe, but they also believe in technology, in science. So...it was a very different world. And the function of music was very different back then. It wasn’t for entertainment, like it is mostly today. Ausra: Yes, but still, I often think about people in those times--imagine you live in sort of like a village somewhere; you work hard to make a living for yourself possible, and you go to church on Sunday. And it’s a nice building, with gold everywhere and nice stained-glass windows and a beautiful altar, and organ, and it plays music. And you know, otherwise it was probably the only chance for people to hear some music. And it should sound for them just like a miracle. I believe so. Vidas: And in general, to experience art, the church was probably the only--or one of the very very few--opportunities in those days. Ausra: And you know, in churches you don’t have, like, places to sit--no benches; so you would just have to stand up or kneel. Vidas: For a long time. Ausra: For a long time, yes. Vidas: Because services were very long. Three hours. Ausra: That’s right. And I’m just thinking this organ music must have sounded to them like something from heaven. Vidas: Definitely, especially if the organ is high in the balcony. People are facing the altar at all times; they don’t see the music coming from the balcony, they only hear this roar of this magnificent instrument. And they think it’s the voice of angels, sometimes, or even God. Ausra: Yes. Yes, that’s right. So I would suggest some recordings, actually, some historical recordings to listen to. And in general, you know, the more you listen to a particular piece--the better you get acquainted with it--the better you can appreciate it. Vidas: Do you think that listening is enough, or should people play it? Ausra: Well, it would be excellent if you could play it, too. Then you could know the piece from the inside out. Vidas: Play it and think about it, right? Like, deeply think about what’s happening in this music. Not on the emotional level, where you would think, “I like it,” or “I don’t like it,” but think about what is actually happening, in musical terms. Ausra: Yes, that’s right. And you know, on modern instruments, you don’t have such a big difference between consonances and dissonances; but if you listen to that music played on historical instruments--or you know, listen to recordings--you can actually very well define consonances and dissonances. And there’s such a difference between them that it just astonishes you! Vidas: For most people, they don’t really have experience with historical temperaments, right? Ausra: Yes, that’s right. Vidas: Sometimes they have recordings, but they practice on modern-day instruments. Like maybe practice organs, maybe electronic organs; they could have some samples of historical temperaments on virtual organs, I believe. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: It’s getting close, the experiments. Of course, the touch is not there at all. It’s not the same as playing clavichord, or historical Italian or French or German or Spanish or Dutch organs. They are all very very different, right? So what people could do is, they could sometimes try to go on tours. Ausra: Yes, that’s a good idea. Vidas: If they could save enough money once in awhile, and go with an organist group. Or not even organists; some people are just lovers of organ music there, and it’s like organ tourism, I think. Ausra: That’s right. So for going to concerts, if you could get the program in advance, that would be a great deal. You could listen to those pieces before going to the actual recital--maybe play them, sight-read them through. Vidas: Exactly. Do some research about the composers and about the music. A lot of early music is online, available for free. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: On Petrucci Music Library, which is available at imslp.org. So you can do lots of findings there. And they even have manuscripts, facsimiles of autographs. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: So enjoy deciphering old tablatures and notations that are unfamiliar to modern eyes. What else? Can we point out a few of the excellent performers, of course, who recorded some fantastic early music? Ausra: Definitely. Vidas: What’s your favorite? Ausra: Harald Vogel, probably. Vidas: You know, there are many, but some organists and performers you should not miss. Harald Vogel is one. Ausra: In the States it would be Kimberley Marshall. Vidas: Definitely. Then...Bill Porter. Ausra: Sure. Vidas: What about Peter Dirksen? Ausra: He’s wonderful too. Vidas: What about Pieter van Dijk? Ausra: I love him! Vidas: Hahahaha! What about Pamela Ruiter-Feenstra? Ausra: Yes, she’s excellent, especially in Tunder’s work. Vidas: What else? We could go on for hours… Ausra: Yes! Vidas: And it’s very risky, because while mentioning some of our favorites, we don’t want to neglect… Ausra: We don’t want to offend the others, yeah! Vidas: So guys, what you should do is check out a few organ academies in Europe. In Sweden Gothenburg, International Organ Academy; then there is Smarano Organ Academy in Italy; and there is in the Netherlands Organ Festival Holland in Alkmaar, So check out all those teachers and organists who are presenting themselves and their teaching in masterclasses. Everyone there is worth your attention and will expand your musical horizons. Ausra: That’s right. Vidas: Ton Koopman and Edoardo Bellotti of course. Ausra: Sure. So there are so many. Vidas: The late Gustav Leonhardt. And we could go on and on, but of course, you can find your own favorites yourself. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: Okay guys! We hope this was helpful to you. Please send us more of your questions; we love helping you grow. And most importantly, apply our tips in your practice, because when you practice… Ausra: Miracles happen. Today we'd like to share our video from our recent trip to Stockholm German church where we played the famous Duben organ.

This is Vidas' intabulation of double choir motet "Ecce Dominus veniet" by Hieronymus Praetorius, a contemporary of Sweelinck from Hamburg. He added multiple organistic passages, runs and florishes to make it sound like a genuine organ piece from the time of Heinrich Scheidemann (mid 17th century) North Germany. Let us know if he succeeded. PS Right now we're very excited to announce that our 2nd e-book is finally ready: I Don't Have Time to Practice Organ Playing (And Other Answers from #AskVidasAndAusra Podcast). Right now it has a low introductory price of $2.99 until August 16. It's dedicated to all our students who don't have enough time in their days and still continue to practice. By Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene (get free updates of new posts here)

Some 17 years ago Vidas and I we were leading this vocal group "Gloria" at Vilnius University St. John's church and sung the first surviving Requiem Mass by Johannes Ockeghem (1410-1497). It might have been the first time this Mass was performed in Lithuania, who knows? The music is enchanting. We first fell in love with this piece by listening to the recording of the Hilliard Ensemble. This Kyrie heals and calms your soul and even perhaps your body, doesn't it? Here's how it sounds on the organ when Vidas recorded it while practicing for More Palatino recital. So for me this event from last Saturday brought some amazing memories from those 17 years ago. By the way, Vidas has recorded a live training on Facebook about some of the things he learned from this recital. If you're not on Facebook, I hope you'll enjoy it on YouTube. Also this morning added two bonus video trainings to his mini course on how to find more opportunities for organ recital. As of this writing, 60 organists have joined it so far. Have to run now and practice Kyrie from Bach's Clavierubung III and later prepare for my harmony lesson with Victoria. Organ practice really moves you beyond mundane existence. I hope you'll do it before you hit the bed tonight. What a joy! PS the above picture is from our yesterday's hike at Belmontas where we walked almost 8000 steps. This place is just 5 minutes drive from Vilnius center and perfect for people who want to get out of town really quick. It was very relaxing for both of us after our strenuous Saturday - Vidas played this recital and I sat in Musicology exams at school from 8:30 AM until 5:00 PM while listening to students SING and play modulations and sequences, sight-read melodies and talk about music history issues. By Vidas Pinkevicius (get free updates of new posts here)

Yesterday I went to our church to practice 4 pieces from Buxheimer Organ Book. This is the German music collection written in the middle of the 15th century, approximately when Christopher Columbus was born, 600 years ago. The pieces in my edition where written in 3 staves but the lowest stave wasn't supposed to be played with pedals. I had to play the two lowest parts with the left hand. The problem is that in the 15th century, it was quite common for voices to cross each other which means that the lowest part can go higher than the middle part. It makes reading such a score quite a burden. What helped me was to slow down my practice tempo significantly and play the resulting three-note chords one by one, almost without the rhythm. In other words, I had to make sure I don't press the next notes without being 100 % certain the notes will be correct. It's only possible in extremely slow tempo. See if this helps you, if you ever have to play music with voice crossing. By Vidas Pinkevicius (get free updates of new posts here)

Before our "Maria Zart" recital last week Ausra and I went to our church and recorded a couple of pieces by Franz Tunder (1614-1667), an important composer from North German Baroque School. He was a predecessor of Dieterich Buxtehude in St. Mary's church in Lubeck. I hope you will enjoy Ausra's playing in these videos: Praeludium in g (Dorian) and Canzona by Tunder A few of our students liked the pieces on this program so much that they asked to prepare the fingering and pedaling for them so that they could learn these gems as well. Therefore I've just finished preparing Tunder's pieces, Wir glauben all an einen Gott, BWV 680 by Bach and the famous Sortie in Eb major by Lefebure-Wely for our Maria Zart collection of practice scores with complete fingering and pedaling (50 % discount is valid until next Wednesday). Last Tuesday after this recital we went to our Unda Maris studio practice and met our student Regina, the senior IT specialist here at Vilnius University without whom administering salaries for faculty and staff would be a lot more difficult task. Regina also happens to love playing the organ. Right now she is working on BWV 554 and is struggling to find time for organ playing because she works until evenings and when she comes home, it's too late to play for the neighbors who want to sleep. So what she does is she practices in her mind while commuting to work on the bus. It takes concentration and focus but it works. So on Tuesday she said that the concept of playing a piece or two from every century of organ repertoire up to the present day in one recital was more interesting for her than a concert of say, just music of one historical period or one composer. What do you think? Do you think that listeners enjoy variety more than unity? |

DON'T MISS A THING! FREE UPDATES BY EMAIL.Thank you!You have successfully joined our subscriber list.  Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas

Authors

Drs. Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene Organists of Vilnius University , creators of Secrets of Organ Playing. Our Hauptwerk Setup:

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

This site participates in the Amazon, Thomann and other affiliate programs, the proceeds of which keep it free for anyone to read.

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed