|

Vidas: Let’s start Episode 112 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. Listen to the audio version here.

And today’s question was sent by Hubertus. He writes: Dear Vidas, thanks for the Boellmann Carillion fingering and pedaling score. One question please. What means the –o and the o in the pedal part, is it the heel position? I’ve never seen this. Awaiting your comments, I thank you. Please tell me how to use the both feet in the first two measures. Thanks. Hubertus. PS Just ordered the Memorization instructions, for hopefully better approach. So Ausra, have you seen my score of Boëllmann’s Carillon? Ausra: Yes, I have seen it. Vidas: And I notate pedaling in 2 ways. The toes are like a pointed tip; that’s regular, everybody knows about this notation. But the heel, I notate instead of letter U, I notate as a circle, or O. Ausra: Actually, that’s a common practice, especially in the United States. So whoever has some American scores, I’m sure they have noticed such type of pedaling. Vidas: And sometimes--not in my scores, but in English scores in the 19th century--they used another system, where, I think, the pedalings were marked above the notes, even the left foot pedals. Ausra: Yeah, but that must be very uncomfortable… Vidas: Quite confusing. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: Because then they would write L for left, R for right, and then you would have to figure out sometimes heel, sometimes toe. I guess back in those days it was common for organists... Ausra: Could be. I don’t think that English organ music used so much pedal that it was a [problem]. Vidas: True. Ausra: Maybe they didn’t have much pedaling. Vidas: But I’ve seen the English edition of Mendelssohn organ works… Ausra: Oh, I see. That’s another story. Vidas: Yeah. It’s confusing. So now we use a more comfortable system; but heels could be used interchangeably: letter U, or a circle. Ausra: That’s right. Vidas: Or O. Ausra: And if, you know, the letter U or letter O is above the staff, that means you have to press that note with your right heel; and if it’s below the lines, it means the left heel. Vidas: And how do you usually notate your heels--O or letter U? Ausra: I usually use letter U. Vidas: Would it be confusing for you to see O? Ausra: No, it wouldn’t be confusing. Vidas: Mhm. The reason I chose to use Letter O for the Carillon by Boëllmann, is that when I do this sometimes on the computer, is that letter U--if it’s not a capital, but small letter u--it has a curious tail to it, the letter. And it’s not the exact sign of “heel,” right? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: For heel we use capital letter U. If I use the capital letter U, then it would be a much larger font than the toe sign. Ausra: Yes, that’s not good either. Vidas: So I would be constantly having to adjust both heel and toe signs. Therefore I chose letter o, small letter o; and therefore toes and heels would be of a similar size. Ausra: So maybe in the future, you just have to add a little note about how you’re pedaling--which sign means what. Vidas: Exactly. Or I could write it in my handwriting; then I don’t have to worry about capital or small letters anymore. Ausra: Yes. So now could you explain to Hubertus about the next half of his question? Vidas: He writes, “Please tell me how to use both feet in the first 2 measures.” So, the principle of the pedaling this piece is very simple, because a lot of time it’s repeating 3 pitches: D, F♯, and E, D, F♯, and E. It’s like a carillon sounds in the pedal. So I start… First of all, I play everything in those 2 opening measures in the left foot. Ausra: Why do you do this? Vidas: Because it’s very low register, in the extreme left. Would you do this differently? Ausra: Well, I might try to hit that F♯ with my right foot--toe. Vidas: Mhm. But then you have to shift your position entirely to the left--your lower body should be facing the F♯. Ausra: Yes I know, I’m looking now at the manual part. It seems that it’s very high notes, especially in the RH... Vidas: Mhm. Ausra: So that way, it would be very uncomfortable to sit. Vidas: Plus, I believe in some cases, you have to push the pedals and add some pistons, right? Or swell pedals. So it’s better to reserve the right foot for that, I guess, especially later. So the way I notated the first 2 measures is like, I begin the D with the toe, but substitute right away with the heel; and then go to F♯, to the toe again of the same foot; and E will be with the heel; and then the next measure too: D, F♯, E, toe substituted to heel, toe, and heel. And this goes on and on. Ausra: Yes. Is it hard for you to play the same figure over and over again in the same pedaling? Vidas: Um, you have to get used to this. Of course, it’s a fast tempo--Allegro giocoso. What does it mean, giocoso? Jokingly? Ausra: Or playfully. Vidas: Playfully, yeah. Ausra: Joyfully. Vidas: So basically it’s a joyful tempo, and brisk pace. Therefore, yes, you have to get used to this low bass line… Ausra: And I believe it might be hard to substitute in such a fast tempo, don’t you think so? On that D--toe to heel? Vidas: I thought about that; but what else could you do? If you cannot use the right foot, you see? Any suggestions? Ausra: Well, yes, try this pedaling, and if you don’t succeed, then maybe just really play that F♯ with your right toe. Vidas: Mhm. So guys, if you have this score of Carillon by Boëllmann, and you’re struggling with playing only with your left foot, see if Ausra’s suggestion helps you--to use both feet. For me, it wasn’t comfortable to shift my lower body that far to the left while the hands would be playing in the upper register all the time, or most of the time. But your physique might be different than ours. You might have longer or shorter legs than I have, so I don’t know. It depends. What do you think, Ausra? Ausra: Well, try all ways, and just see what works for you. Vidas: Exactly. And please send us more of your questions; we love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice… Ausra: Miracles happen.

Comments

Vidas: Let’s start Episode 111 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. And today’s question was sent by Robert. He writes:

Hi Vidas. Robert here from Vancouver, Canada. I was wondering if it is possible to find the booklet from August Reinhard Op. 74. Heft I (so first half). I have the second half. In German it's "50 Übungs und Vortragsstücke für Harmonium”. As I mentioned I have the second half but it would be nice to get the first half too, to complete the set. It's great stuff! Keep up the wonderful work you both do, and so now and then I keep purchasing a piece you've worked out if I can manage it. I'm still working on BWV 577. I find it hard to get it fast and smooth. Slowly! Blessings, Robert First of all, Ausra, Robert asks for the piece collection and etudes, basically exercises, for harmonium. And I found it online, available from the publisher Heinrichshofen. And I think they have the entire set of 50 exercises here. And I will include the link in the description of this conversation, so that Robert and other people could check it out. Ausra: Excellent. I think this should be a nice source for church organists. Vidas: I think it’s like etudes, right? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: They are not necessarily created as chorale-based melodies or chants. As we see it in the preview, they’re like short preludes, basically, in many keys. Ausra: So you could use them for preludes or postludes Vidas: You could use them on the organ, too. Ausra: Yes, definitely. Vidas: Uh-huh. And they are without pedal. Excellent. So the second half of the question was something we can talk about. Robert finds it hard to get the Gigue Fugue by Bach fast and smooth. Difficult for him, right? Ausra: Well, that’s a gigue. Gigues are all hard to play--you know, to keep a nice tempo. But maybe, you know, he wants to play too fast too soon? Vidas: That’s my impression, too. Maybe people sometimes get frustrated with their progress and they want to advance faster than they should; they pick up the tempo sooner than they are ready. Ausra: Yes. Of course, you know, they’re playing pieces based on dances: like gigue, gavotte, and minuet, and others. It’s very important to keep up strong and weak beats. All this pulse is necessary. It’s necessary in any piece, but especially in those that are based on dances. Vidas: Because if you listen to pop music, right-- Ausra: Yeah... Vidas: They’re entirely based on dances, right? And in pop music, rhythm is the most important element. Ausra: So, like playing the Gigue Fugue, you know, rhythm is the most important. At least, that’s my opinion about it. Vidas: Mhm. So if Robert can play it slowly enough that he will have good pulse, is he on the right track? Ausra: I think so, yes. Because he will add tempo later. Actually, the tempo will speed up itself. Vidas: When he’s ready? Ausra: Yes, that’s right. Vidas: Are there any tricks/shortcuts to take? Ausra: I don’t think so. Vidas: We’re in the wrong business, right? Ausra: Yes, yes, that’s right. Vidas: We’re not in the business of shortcuts. If we were, we wouldn’t be here, actually, recording this, because we would have been frustrated sooner than we would have sensed the advancement of the results, and we would have quit a long time ago. Ausra: Yes, that’s right. Vidas: But perhaps Robert and others who are frustrated with their progress in fast pieces can enjoy moments of the entire process. Not necessarily the result, which is slow, but the process--what they have achieved today. Ausra: Yes. And you know, this might comfort you: keep in mind that gigue is the hardest of dances to play, so it’s natural that you have some trouble now. But I hope that you will overcome those troubles. Vidas: It seems that people like Robert sometimes get too focused on one piece, and they spend months on one piece. Is that a productive strategy? Ausra: I think sometimes it’s better to divide your focus on several pieces. Vidas: And practice and perfect the piece only to a basic level, right? And then go to the next piece, and to the next piece, and to the next piece; and only after a few months, he can come back to this Gigue. Ausra: Yes; sometimes it’s good to take a break on a piece, and return back after some time. Vidas: Tell me when you found yourself in such a situation--when the piece was frustrating for you, and you had to go to something else, something more exciting for you at the moment; and then you came back and noticed something different and more advanced. Ausra: Yes; that’s what I’ve felt, actually, quite a few times. And sometimes it’s enough only to take a break for only like 2 or 3 days, and come back to a piece, and it’s already easy--it seems already easy. Vidas: Like when we’re preparing for this weekend’s recital, sometimes we skip a day, right? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: And it gets better, actually, because of that. Because we play so often together, and sometimes it gets stuck in one...mode of playing. And if we give it a break, then we can come back with a fresh mind. Ausra: That’s right. Vidas: Sort of, we start to miss our playing then, right? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: You have to miss it. And then come back. Ausra: Plus, also some technical things: If you are practicing day after day after day, especially in a fast tempo, things might get muddy, unclear. So sometimes it’s nice to have a rest, and come back later. And then it seems much better, much easier. Vidas: Excellent. So guys, we hope that this advice was helpful to you. Try to apply it in your practice. And send us more of your questions, right Ausra? Ausra: Yes! We are waiting for them! Vidas: And remember, when you practice… Ausra: Miracles happen. Welcome to Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast #121!

Vidas: Let’s start Episode 110 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. And today’s question was sent by Kevin. And he writes:

Thanks for sending the week 2 materials for Prelude Improvisation Formula. I have enjoyed working through week 1 modulation exercises. My goal was to start Descending Sequence 2 and keep going until I passed through all the closely related keys without stopping! This goal was a little too ambitious at first. I made progress taking one modulation at a time, and I found that modulating to keys with two accidentals is much smoother adding one change at a time instead of all at once. Walther's elegant pitches from Pamela Ruiter-Feenstra's Volume 1 of Bach and the Art of Improvisation are also helpful. Thanks again Vidas. Learning how to improvise in the style of J.S. Bach is the realization a lifelong dream. So Ausra, Kevin apparently practices materials from a few sources: first of all, from Pamela’s book, and from my prelude improvisation formula. And he wants to learn to improvise in the historical styles. We could congratulate him, right? Ausra: Definitely, yes. That’s a big goal. Like he said, a lifelong dream. Vidas: People love to emulate historical styles in their improvisations for several reasons. Probably the most important one is that they love early music to begin with, right? Ausra: That’s right. Plus, I think that modern style has almost exhausted all possibilities already, and people are sort of returning to the origins of music and to early music--to Bach’s music. Vidas: And if you play your favorite composer long enough, you sort of wish that he or she would have composed more music, right? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: And then, of course, you’re left with a question: maybe you yourself can recreate this tradition in modern days, and try to create music on the paper or on the spot, at the instrument, spontaneously, just like, for example, Bach would do, back some 300 years ago. Ausra: Yes, and you know, for Kevin I think it would be helpful to listen to some improvisations by Sietze de Vries. Vidas: From the Netherlands? Ausra: Yes, because he is sort of improvising in the style of Bach; so he might get new ideas of how to do it. Vidas: There are a couple of my other favorites: William Porter and Edoardo Bellotti]. Ausra: Yes, they are excellent, too. Vidas: You know, a lot of music which was composed back in the day could serve you as models today. They were meant, actually, to be models for students--not only as technical exercises and pieces to be performed in public. Sure, there were some; but the majority of musical examples were used as models for composition and improvisation. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: So what could Kevin do in this case? Ausra: Yes, he could also study some pieces and imagine that these are models of how to improvise. Vidas: Pamela talks in her Volume One (and now in Volume 2, just recently published) of her improvisation treatise, that the goal of this book and her lifelong work is to present the tools for students so that they could decipher any type of style. If they love Bach, that’s good; if they love Sweelinck, they could do the same deciphering with Sweelinck works. Ausra: That’s right, you could do that with any composer. Vidas: If they love Franck’s work, they could find out how the piece is put together, and then do all those exercises with Franck’s style. And if they love jazz, they could decipher jazz style--the same thing. And modern style, as well. They just need to learn to use the tools. Ausra: That’s right. You can basically apply one formula to any composition. Vidas: Yes. So I think Kevin is on the right track. He is studying from these sources; but try to go back to primary sources-- Ausra: Yes. Vidas: Not only from my material and Pamela’s book (which of course will be helpful), but go back to the origins, to the composer themselves. See what they have created. Ausra: And another thing, if you want to become a fluent improviser, you might practice more sequences, modulations, cadences. Vidas: That’s what Kevin is talking about, right? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: Descending sequences. Ausra: Yes, yes. So, on YouTube I believe he can find many of my sequences and modulations and cadences. That will just help you to be able to play equally well in any key; and since Bach already used all the keys, so you need to be fluent in every key. Vidas: Definitely. Because sequences will sort of help you transfer one musical idea to many different settings--higher, lower, with sharps, with flats--the same idea, but presented higher or lower, in a predetermined manner, in various intervals or in closely related keys which are just maybe 1 accidental apart or so. So, Ausra, you’re absolutely right. When was the time for you, in your life, when you cracked the secret of sequences? Ausra: Well, that was a long time ago. Vidas: At school? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: Did you like playing those sequences at school? Ausra: Yes, I liked it, actually; I enjoyed it much more than harmonizing the given melody or given bass. Vidas: Yesterday (we’re recording this on Sunday, but) yesterday you taught a group of Lithuanian organists how to harmonize, right? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: So, how was your experience with them? Ausra: It was fun. I had a great time. Vidas: What did you feel they learned the most from you? Ausra: I don’t know. Probably some just refreshed their memory with things they knew way back and had forgotten. And for some, it was just a new thing, and I don’t know how much information they were able to digest. But I hope that everybody learned something. Vidas: Isn’t that--harmonization--sort of the first step in improvisation? Ausra: I think so, yes. Vidas: Because if you learn to harmonize a melody, you are very very close to developing this idea even further. Ausra: That’s right. Vidas: To adding some passing tones, nonharmonic tones, to add maybe another melody in another voice, or add some dialogues between the parts in certain rhythmic formulas. Ausra: I think that harmony is sort of a foundation to other disciplines, such as improvisation of course, and composition. Maybe I would say composition first, and then improvisation. Vidas: So, to be a complete musician, to be a complete organist--as we say, total organist-- Ausra: Yes? Vidas: Do you think that people would benefit from all those additional theoretical disciplines like improvisation, harmony, of course theory...? Ausra: Yes, that’s right. Vidas: Composition? Ausra: Yes, that’s right. That’s right. I don’t understand how some musicians just oppose these things, because I think that theory and practice/practical things should go side by side. Vidas: They’re like two sides of the same coin. Ausra: That’s right. And people who do one and avoid the other one--I think they make a big mistake. Vidas: Theory without practice is dry and miserable. Ausra: Yes, that’s right. Vidas: It’s boring. And sometimes we make this mistake at school, right? We teach them theory without any applications, and people don’t understand--especially the youth--don’t understand why they need this. On the other hand, practice without theory… Ausra: Without understanding what you are doing… Vidas: Doesn’t lead anywhere. Ausra: I know. You can, you know, teach a bear to learn how to ride a bike; but probably the bear will never understand how the bike is constructed. Vidas: And will never be able to teach other bears how to ride the bike. Ausra: That’s right, that’s right. Vidas: So that’s what we’re doing. We’re trying to help you grow as a total musician--total organist--so that you later could transfer this knowledge and this tradition to other people, perhaps. Ausra: That’s right, that’s so important. To keep this tradition going. Vidas: Yes. And creativity is key. If we’re not creating, something is wrong with us, right? With creativity, we’re different from other species, right, of beings on this planet. So improvisation and composition are those two ways that our creativity can manifest itself. Ausra: That’s right. Vidas: And improvisation in historical styles can get us closer to our origins, to our old masters. Ausra: That’s right. So guys, please apply our tips in your practice, and send us more questions. Vidas: And remember, when you practice… Ausra: Miracles happen.

Vidas: Let’s start Episode 109 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. Today’s question was sent by Barbara, and she writes:

Dear Vidas and Ausra, You are very welcome. Your emails have already answered many questions -- some I didn't even know I had -- everything from why some of your fingerings are so different to how to hear inner voices to how to deal with injuries. Thank you! And thank you very much for the Boellmann toccata. I actually learned it many years ago when I was still taking organ lessons (I started lessons 18 years ago at age 48). I played it for a Halloween postlude one year at my church, and they brought the Sunday school in to listen, so I really pulled out all the stops at the end. But I'm very glad to have your fingering. I've been on retirement "vacation" for many months because of numbness in my hands, so I've been trying new fingerings as I ease back into things (long story, but I think I've been using too much piano technique on the organ all these years and it's taken its toll, especially as my muscles and joints age). Thinking of a question for you is a little like having to choose one wish for a fairy godmother. But here goes. One of my current struggles is being a better listener at concerts and recitals where the music is unfamiliar. I've learned a lot about baroque/classical/romantic music, but I don't know how to fully appreciate early music, especially music written before tempering. Do you have any suggestions for how to approach this? Recommendations for good listening collections of music using specific modes or styles? I this will also help me to better appreciate organ improvisations and modern music. Many, many thanks again for all you do. Best wishes to you both, Barbara What do you think, Ausra? Ausra: Very nice letter. And a very interesting question, actually. Well you know, in order to be better able to understand early music, you would probably need to listen to some recordings of this music performed on original instruments, on historical instruments. Because this makes all the difference in the world. On the modern instruments, performing early music doesn’t sound good enough--or not as good as it should sound on the original instruments. What do you think about that, Vidas? Vidas: With a few exceptions. If music is more familiar to modern ears--let’s say the style is more familiar, like one of Johann Sebastian Bach’s--then it sounds good on almost any type of instrument, right? Ausra: Yes, that’s true. But I’m talking about even earlier music. Vidas: Mhm. Ausra: Like Robertsbridge Codex and that kind of music. Vidas: Yes, we have to understand here that people who wrote similar pieces 700 years ago were living in times that the mentality was closer to pagans in the ages before Christ than to our modern days. Because they were basically completely, as they say, world-conscious; they believed in higher powers. And today’s people still do believe, but they also believe in technology, in science. So...it was a very different world. And the function of music was very different back then. It wasn’t for entertainment, like it is mostly today. Ausra: Yes, but still, I often think about people in those times--imagine you live in sort of like a village somewhere; you work hard to make a living for yourself possible, and you go to church on Sunday. And it’s a nice building, with gold everywhere and nice stained-glass windows and a beautiful altar, and organ, and it plays music. And you know, otherwise it was probably the only chance for people to hear some music. And it should sound for them just like a miracle. I believe so. Vidas: And in general, to experience art, the church was probably the only--or one of the very very few--opportunities in those days. Ausra: And you know, in churches you don’t have, like, places to sit--no benches; so you would just have to stand up or kneel. Vidas: For a long time. Ausra: For a long time, yes. Vidas: Because services were very long. Three hours. Ausra: That’s right. And I’m just thinking this organ music must have sounded to them like something from heaven. Vidas: Definitely, especially if the organ is high in the balcony. People are facing the altar at all times; they don’t see the music coming from the balcony, they only hear this roar of this magnificent instrument. And they think it’s the voice of angels, sometimes, or even God. Ausra: Yes. Yes, that’s right. So I would suggest some recordings, actually, some historical recordings to listen to. And in general, you know, the more you listen to a particular piece--the better you get acquainted with it--the better you can appreciate it. Vidas: Do you think that listening is enough, or should people play it? Ausra: Well, it would be excellent if you could play it, too. Then you could know the piece from the inside out. Vidas: Play it and think about it, right? Like, deeply think about what’s happening in this music. Not on the emotional level, where you would think, “I like it,” or “I don’t like it,” but think about what is actually happening, in musical terms. Ausra: Yes, that’s right. And you know, on modern instruments, you don’t have such a big difference between consonances and dissonances; but if you listen to that music played on historical instruments--or you know, listen to recordings--you can actually very well define consonances and dissonances. And there’s such a difference between them that it just astonishes you! Vidas: For most people, they don’t really have experience with historical temperaments, right? Ausra: Yes, that’s right. Vidas: Sometimes they have recordings, but they practice on modern-day instruments. Like maybe practice organs, maybe electronic organs; they could have some samples of historical temperaments on virtual organs, I believe. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: It’s getting close, the experiments. Of course, the touch is not there at all. It’s not the same as playing clavichord, or historical Italian or French or German or Spanish or Dutch organs. They are all very very different, right? So what people could do is, they could sometimes try to go on tours. Ausra: Yes, that’s a good idea. Vidas: If they could save enough money once in awhile, and go with an organist group. Or not even organists; some people are just lovers of organ music there, and it’s like organ tourism, I think. Ausra: That’s right. So for going to concerts, if you could get the program in advance, that would be a great deal. You could listen to those pieces before going to the actual recital--maybe play them, sight-read them through. Vidas: Exactly. Do some research about the composers and about the music. A lot of early music is online, available for free. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: On Petrucci Music Library, which is available at imslp.org. So you can do lots of findings there. And they even have manuscripts, facsimiles of autographs. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: So enjoy deciphering old tablatures and notations that are unfamiliar to modern eyes. What else? Can we point out a few of the excellent performers, of course, who recorded some fantastic early music? Ausra: Definitely. Vidas: What’s your favorite? Ausra: Harald Vogel, probably. Vidas: You know, there are many, but some organists and performers you should not miss. Harald Vogel is one. Ausra: In the States it would be Kimberley Marshall. Vidas: Definitely. Then...Bill Porter. Ausra: Sure. Vidas: What about Peter Dirksen? Ausra: He’s wonderful too. Vidas: What about Pieter van Dijk? Ausra: I love him! Vidas: Hahahaha! What about Pamela Ruiter-Feenstra? Ausra: Yes, she’s excellent, especially in Tunder’s work. Vidas: What else? We could go on for hours… Ausra: Yes! Vidas: And it’s very risky, because while mentioning some of our favorites, we don’t want to neglect… Ausra: We don’t want to offend the others, yeah! Vidas: So guys, what you should do is check out a few organ academies in Europe. In Sweden Gothenburg, International Organ Academy; then there is Smarano Organ Academy in Italy; and there is in the Netherlands Organ Festival Holland in Alkmaar, So check out all those teachers and organists who are presenting themselves and their teaching in masterclasses. Everyone there is worth your attention and will expand your musical horizons. Ausra: That’s right. Vidas: Ton Koopman and Edoardo Bellotti of course. Ausra: Sure. So there are so many. Vidas: The late Gustav Leonhardt. And we could go on and on, but of course, you can find your own favorites yourself. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: Okay guys! We hope this was helpful to you. Please send us more of your questions; we love helping you grow. And most importantly, apply our tips in your practice, because when you practice… Ausra: Miracles happen.

Vidas: Let’s start Episode 108 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. This question was sent by Andrew, and he writes:

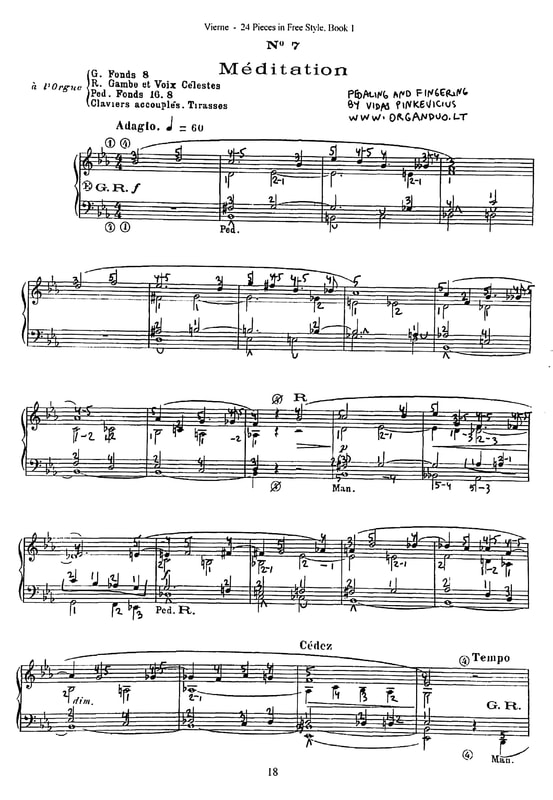

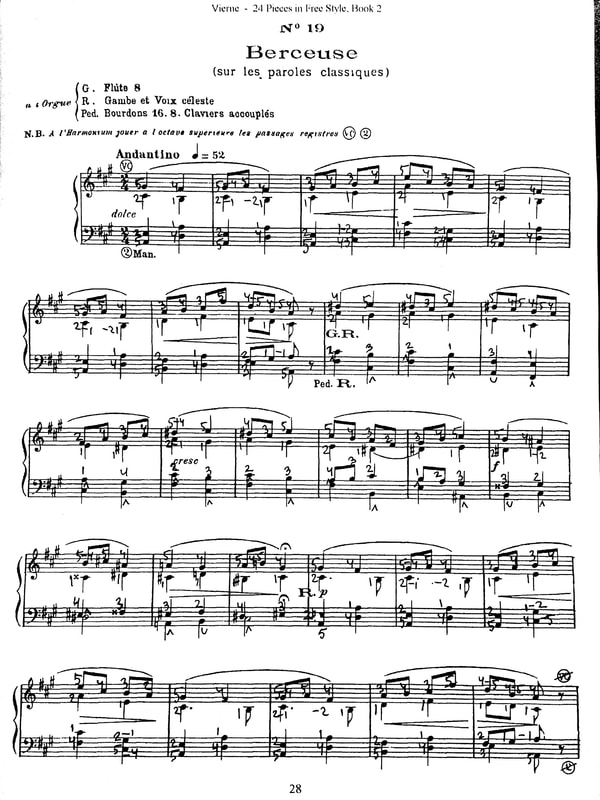

“Dear Vidas, thank you for your email particularly since you must be very busy judging by all your posts! In reply to your question, I’m currently working on Franck's Final, and hoping to move on to Stanford’s “Rheims” from the second organ sonata, hopefully in time for Armistice Day 2018.. I visited Rheims last year. What do I struggle with? Early fingering and ornamentation, particularly making Early English music sound coherent and fluid. Andrew” So, early English music--that’s probably John Bull, Orlando Gibbons. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: Redford, Tallis... Ausra: William Byrd... Vidas: Byrd, yes. These things. Basically… Fitzwilliam collection. The collection is enormous--it has 2 gigantic volumes-- Ausra: Wonderful collection, yes. Vidas: And I don’t even know how many hundreds of pieces there are from the time of before Purcell, I think--16th century, end of 16th century, late Renaissance; right, Ausra? Ausra: Yes. And I think this collection also includes music by Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck. Vidas: Yes. Ausra: The only one, I think, non-English composer. Vidas: Exactly. So, all those wonderful English composers have a lot of passage work and runs with each hand sometimes, and many many ornamentation instances. Ausra: Yes, you have to be a virtuoso to be able to play these pieces. But there is also a good side about this music: it almost doesn’t have pedal. So you can play it not only on the organ, but also on the harpsichord, and also on the clavichord or virginal. Vidas: Exactly. A virginal is a smaller version of the harpsichord, like a spinet, sort of. Ausra: Yes, it’s really small. Tiny. Vidas: And it works well on the organ, too, I would say. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: I played, a few years ago, in our long recital based on this collection which was devoted to English composers, and I sort of liked it, because then of course, I had to figure out my registration, because it’s not written in the score (because it’s really not for the organ); but I had some imagination with this, and our church organ at Vilnius University St. John’s Church was quite colorful. Ausra: Yes, and what actually helped me to be able to play early music better was the clavichord. Actually, basically the clavichord was the instrument that showed me, really, how to play early music well. Vidas: What’s so unique about the clavichord, Ausra? Ausra: Well, it’s sort of an instrument that teaches you. Teaches you to use correct fingering, then to use the right touch on the keyboard. And if you would be able to play a piece of music on the clavichord well, it will sound good on the organ, too. Vidas: Historical clavichords have shorter keys and very narrow keys; and the touch is so light. And it seems like it’s very easy to play; but it’s not, because you have to use all the big muscles of your back, basically, to give some weight on the keys. Ausra: Yes, yes. And because it’s different from the organ and harpsichord. Because on the organ or harpsichord you can make the sound louder or softer only by adding or omitting stops; but while playing clavichord, you can do actual dynamics just by touch. Vidas: Yeah. And remember, you can do vibrato. Ausra: Bebung, so-called Bebung. Vidas: In German, Bebung, yeah--by gently pressing the key up and down, giving this constant pressure--up and down, up and down. And that’s what the vibration comes from. Ausra: Yes, and then playing on the clavichord, you understand what the meaning of the early fingering is. Because it’s impossible to play early music well on the clavichord while using modern fingering. Vidas: Exactly. So it’s very well suited for English music from the late Renaissance and early Baroque, especially because as we said, the key are very narrow, and the touch is very light, but you have to avoid thumb glissandos. Ausra: Yes, use position fingering. And by position fingering I mean you cannot use the thumb under… Vidas: Under--crossing the thumb under, you mean. Ausra: Yes, crossing the thumb under. Vidas: When you play a scale, for example, from C to C, then in modern fingering we do 1-2-3, 1-2-3-4. Ausra: And then 5-1-5. Vidas: So on the note F, we press with 1. And this thumb… Ausra: Goes under. Vidas: Under your palm. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: And crosses. Ausra: So you cannot do that while playing early music? Vidas: You have to keep positions. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: And shifting the entire palm into the new position. Ausra: That’s right. And also use a lot of the paired fingering. So if you have a passage with your RH, then the good fingers would be 3-4, 3-4, 3-4. Vidas: Yes. Ausra: If you are playing with your LH, the good fingering would be 2-3, 2-3, 2-3. Vidas: And it depends on the region and the country. Sometimes 1-2, 1-2, with Sweelinck, for example. But I wouldn’t worry too much about the differences between the countries--it’s too advanced detail. In general, use paired fingering for passages that remind you of scales. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: And keep position fingering for everything else. Ausra: And if you don’t have access to a clavichord, then practice on the harpsichord, or practice on a mechanical organ. Because if you only practice on an electrical organ or pneumatical organ, it will not do good for such music as early English music. Vidas: Well yes, it will sound unnatural for these modern instruments. And quite boring. Ausra: Yes, it will sound boring on the pneumatical or electric instrument. Vidas: Exactly. So then, another point is about ornamentation. Which fingers do you make ornaments with? Ausra: Well, if I’m playing a trill with my RH, I could do either 2-3 or 3-4. It doesn’t make much difference for me. Vidas: Mhm. Ausra: And actually, with my LH, I could do a trill with 3-2 or 3-1 sometimes even, maybe not so often 3-4 with the LH. Vidas: Mhm, mhm. Ausra: But I could do it. Vidas: For a long time I was amazed how you can do a trill with 3 and 4 with your RH, and I kind of avoided this myself; and only now I’m getting better with 3 and 4. My technique is getting better, I mean. Ausra: Good! I’m glad to hear it. Vidas: So, we’re all making progress, right? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: So guys, keep practicing slowly, especially on mechanical action instruments. Ausra: And you know, if you are struggling with ornaments, I would suggest you learn to play the pieces without ornaments first. Because what I have encountered while working with other people, or remembering the early age of my practice, is that if I tried to play ornaments right away, I would never play them well; and I could never keep a steady tempo in the piece. Vidas: Mhmmm. Ausra: So, you need to learn your music right rhythmically, without ornaments first. And when you are fluent with the music score, with all the musical text, then add ornaments. Vidas: Strange, I kind of forgot how I first learned music. And nowadays I’m learning with ornaments, of course--everything at once; but this is today, after 25 years of experience. So maybe other people need to simplify things at first. Ausra: Yes. And you know, if there are some ornaments that you are not able to play well, then just avoid them. Because nobody ruins a piece so well as playing ornaments in a bad manner, or you know, too slowly. Because they need to sound graceful. They are ornaments. And if some of them are just too difficult for you, then just don’t play them. That’s my suggestion. Vidas: Good. I agree. Please, guys, practice like we suggest; it really makes a difference in the long run. And keep sending us your questions; we love helping you grow. This was Vidas. Ausra: And Ausra. Vidas: And remember, when you practice… Ausra: Miracles happen. If you want to learn Berceuse, Meditation and Allegretto by Louis Vierne, please check out my PDF practice scores with fingering and pedaling written in.

50 % discount is valid until November 22. These pieces are free for Total Organist students.

Vidas: Let’s start Episode 107 of #AskVidasAndAusra podcast. This question was sent by Brice, and here is how it sounds:

“When I learn a piece of music depending on its difficulty I can learn it in several hours, or several days, several weeks or 1 to 2 months. Don't mind taking a lot of time to learn to music, but I'd like it so that I can get myself up to the level where I read simple pieces of music down to less than an hour if not 30 to 20 minutes to learn. Or be able to just sight read such a easy piece.” Basically, this question is about the level of fluency in sight-reading, yes Ausra? Ausra: Yes, or learning music faster. Vidas: So we probably have to advise people to just keep practicing sight-reading, right? Ausra: Yes, I think that would be the easiest way to reach the level you want to be at. Vidas: Of course, Brice is concerned about the time it takes to do this, right? The amount of practice. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: Apparently, the level of skill is getting better--but too slowly for Brice. Ausra: Well, it would be excellent in such a case to find a church position, if he doesn’t have one. That way, you would just be forced to do it. Vidas: Every week. Ausra: Yes, every week… Vidas: Maybe several times a week. Ausra: Maybe several services a week, and new repertoire all the time--prelude, postlude, offering, hymns...And this would make things easier after a while. Of course, you would suffer at first; you would have to play a lot, but eventually it would get easier. Vidas: I struggled with sight-reading for a very long time. I remember my first piece was, I think, “Jesu meine Freude” from Orgelbüchlein. In the 10th grade, my teacher gave it to me, to choose from any chorale; and I chose this piece. And I couldn’t sight-read even the hands part fluently enough at a slow tempo. I was struggling at the level that I even didn’t understand how the piece is put together. What about you? Ausra: Well yes, I basically was a good sight-reader from a very early age; but the thing is that after playing music the second time, it wouldn’t get much better than sight-reading it! So I had my struggles, too. But I remember when I worked at a Christian Scientist church while I was studying in Michigan--well, it was a nice job, actually, to have. But I remember each week, the reader who would lead service that Sunday would call me and leave the hymn numbers on my answering machine, in order for me to be able to learn them for Sunday. And first of all, yes I would do that: I would play them, prepare them in advance, be worried that everything would go well; but after maybe playing for like half a year in that church, I would never play those hymns in advance--I would never prepare them in advance. I would just show up on Sunday and play for the service. Because I didn’t need to do it. Vidas: You were good enough? Ausra: Yes, yes. Vidas: Mhm. For me, I think, the struggle continued even until late years in America, I think. But yes, this position that we both shared--Grace Lutheran Church, but even earlier in Michigan, I worked in Ypsilanti Missouri Synod Lutheran Church there; and I also had to provide a lot of hymns, preludes, postludes, communion music, offertories, regularly, sometimes several times a week, even for funerals. So gradually, I found out that really, I’m getting better at this. I hated to spend too much time with learning the music, so I really sightread everything. So after maybe 2 months of doing this intensely, I suddenly realized a breakthrough. Ausra: Yes. And of course, your theoretical background--of understanding the theory of music--is also very important in order to be able to learn music fast or sight-read well. Because knowing all those clefs and key signatures--that’s what makes you to sight-read music easily. Vidas: Basically, your brain has to connect the dots for you-- Ausra: Sure, sure. Vidas: To know the meaning behind the notes. Ausra: That’s right. Because usually, you know, if you read a piece of music in C Major, it’s easier than to read, for example, music in D♭ Major. Vidas: Mhm. Ausra: The more key accidentals you get, the harder it is. And of course, it’s easy to sight-read, let’s say, a hymn, because it might have like, a few secondary dominants; but that’s almost the hardest theoretical thing you can get in a hymn. But if you are learning a piece of music from such a composer as Max Reger, for example, which has such chromatic harmony… Vidas: Or Louis Vierne. Ausra: Yes. So, it adds much more difficulty. Vidas: I think people should not rush into very advanced pieces too early. Ausra: Yes; and you know, I think if you want to sight-read music fast and well, and be able to learn music fast enough, you need to pick up easy repertoire for beginners. Vidas: Mhm. Ausra: There are some very good examples of music that sounds good, but it’s not as hard to learn, for beginners. Like, for example, Frescobaldi’s “Fiori Musicali”. That’s a wonderful collection for church musicians. Or you know, if you want Romantic music, pick up Cesar Franck’s “L’Organiste”. That’s an excellent collection. Vidas: Or Alexandre Guilmant wrote Practical Organist and Liturgical Organist. Those collections also have short pieces based sometimes on chants, sometimes not on chants; but they’re suited for church playing. And they’re beautiful pieces, but not too difficult. Ausra: Yes. Vidas: And sometimes they are with pedal, sometimes without; you can have optional pedal lines, like for harmonium, without any pedals; but you can add pedals, playing the bass with your feet. Ausra: Yes. So if you don’t have much time to prepare your music, pick up easy music for beginners; and then together with that, at the same time, you can learn (slower) harder pieces. Vidas: Another thing to consider is to start improvising. Right? It does help, too. Ausra: Well, yes, it does help, too, but it will not make you a better sight-reader. Vidas: Why not? Ausra: Because when you improvise, you don’t have a music score in front of you. And I think if you just improvise, eventually you might not be able to play from the sheet music at all. That’s my opinion. Vidas: Here I agree with you, but I also have another perspective on this. If you improvise freely from your imagination, then yes, the skill of reading music is something different. But if you are thinking in terms of harmony and counterpoint, like the piece is really written out in your mind, then it helps, eventually. Ausra: Well, I see your point; but improvisation like this, as you described it, will take you even more time than learning music from the score. Vidas: So guys, choose whatever works for you. We’re only sharing our perspectives and experiences, right? Ausra: Yes. Vidas: Wonderful. And of course, apply our tips in your practice, if you like them. That makes all the difference. And please send us more of your questions; we love helping you grow. This was Vidas. Ausra: And Ausra. Vidas: And remember, when you practice… Ausra: Miracles happen. Last Saturday Ausra taught Harmony seminar at Vilnius University to some 40 church organists from all over Lithuania. I had a pleasure sitting through it and writing in fingering and pedaling for the Dubois Toccata.

At the same time other organists taught classes on church music, Gregorian chant and other subjects relevant to liturgical musicians. In the evening everyone gathered at our church for a joint recital. Masterclasses "Organ for the Future of Lithuania" were organized by the National Association of Organists. My friend and student Paulius Grigonis performed at this joint recital. He played the famous "Berceuse" by Louis Vierne. Incidentally, I had with me my score in which I kept writing in fingering and pedaling. When others saw me writing something in the score, they asked me what I was doing to which I jokingly replied, "I'm writing fingering and pedaling for Paulius so that he could play it tonight." Actually, this wasn't very far from the truth. Vierne's "Berceuse" sounded towards the end of the program and by the time Paulius' turn had come, I had almost finished the editing process. I hope you'll enjoy playing this piece yourself from my PDF score (3 pages). I've edited it to be played with pedals and two manuals even though "Berceuse" was originally published on two staves. Here the bottom stave is mostly shared by the left hand and the feet parts. Let me know how your practice goes. 50 % discount is valid until November 15. This score is free for Total Organist students. Welcome to Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast #120!

Today's guest is Dr. Pamela Ruiter-Feenstra who is an American organist, international performer, composer, liturgical musician, scholar, and pedagogue. She returns to our show to introduce our listeners to the newly published Vol. 2 of her treatise "Bach and the Art of Improvisation". Here's our previous conversation about Vol. 1. Simultaneously revolutionary and realistic, Pamela Ruiter-Feenstra resuscitates historic improvisation from relevant treatises and documentation of Bach's improvisation pedagogy in counterpoint with tried and true applications. She incrementally guides the reader from improvising cadences, chorales, partitas, and dances in Volume One to improvising interludes & cadenzas, preludes, fantasias, continuo playing, and ultimately, fugues in Volume Two of Bach and the Art of Improvisation. The chapters on continuo playing alone beckon reform of current practice. Pamela invites those willing to immerse themselves in improvisation to embody consummate musicianship as theory, history, aural perception, and soul-communicative playing come to life in practice and performance. Enjoy and share your comments below. And don't forget to help spread the word about the SOP Podcast by sharing it with your organist friends. And if you like it, please head over to iTunes and leave a rating and review. This helps to get this podcast in front of more organists who would find it helpful. Thanks for caring. Listen to the conversation Relevant links: http://www.pamelaruiterfeenstra.com/bach__the_art_of_improvisation_2 http://www.pamelaruiterfeenstra.com/bach__continuo_bai_2_audio/ |

DON'T MISS A THING! FREE UPDATES BY EMAIL.Thank you!You have successfully joined our subscriber list.  Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas

Authors

Drs. Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene Organists of Vilnius University , creators of Secrets of Organ Playing. Our Hauptwerk Setup:

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

This site participates in the Amazon, Thomann and other affiliate programs, the proceeds of which keep it free for anyone to read.

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed