|

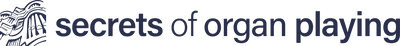

I have created this score with the hope that it will help my students who love early music to recreate articulate legato style automatically, almost without thinking. Thanks to Alan Peterson for his meticulous transcription of fingering from the slow motion video. Basic level. PDF score. 1.5 pages. 50% discount is valid until October 28. Check it out here This score is free for Total Organist students.

Comments

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 310, of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by C.K. And C.K. writes: C.K. Hi Vidas, 1. My dream is to become a competent, versatile and creative church organist. V: And the obstacles toward this dream are, C.K. 2. Modulation skill; improvisation technique; setting registration. Regards, C K V: Uh-huh. So, C.K., basically wants to play in church, very creatively and confidently. And in a varied fashion. But he struggles with modulating, improvising and registration. A: So this goes to shows that he needs to deepen his music theory knowledge. And the last one, setting registration. I think it’s the problem of probably understanding the organ itself and maybe what fits what. V: Yes. If you were to start answering this question, I think starting talking about the last one would be the easiest starting point, right? A: Yes, I would think so. V: Registration. Let’s imagine, Ausra, you are summoned to St. John’s church today because we’re recording it on Sunday, to play for a mass, right? In the Catholic mass, we have a number of hymns to sing sometimes. Although I usually play organ music improvised, but other people do sing hymns. If you were to play hymns, what would you think about when setting the registration? A: Well, I would be thinking how many people are attending church; are they all singing hymns or am I singing solo. And I would make up registration accordingly. V: Would you use all manuals in that organ, or just one? A: What, for hymn accompanying? V: Yeah. For one hymn for example. A: Well, you could use one, but it would be nice to use two, or three especially if you don’t want to change the stops in the middle of the, during verse. V: If the hymn has three stanzas, you could easily play on one, two and three. A: Yes, and do them in different volume. V: Or even if you have four stanzas, you could play one, two, three and one again. A: That’s right. V: Basically jumping from manual to manual is a good way to change colors, because when playing on the second manual, you could change the first manual also, a little bit. With one hand you could still play and with another you could draw one or two stops. A: Yes. That’s when you are playing mechanical organ but if you have electric organ or something with piston system then it’s much easier. V: Mmm-hmm. A: You just push a button, that’s it. V: I think for C.K. to understand registration of hymns and accompanying them in the liturgy, the starting point probably needs to be, to use principle chorus, right? A: That’s right. V: If the congregation is big you could play with mixtures. If it’s not big you could play actually 8’, 4’ and 2’ or just 8’ and 4’. 8’ and 4’ would be enough for a small congregation probably. Don’t you think? A: That’s right. V: What about 16’ in the manuals? That would be nice too. A: Yes. You could add that too. V: If you have mixtures, right? A: Yes. V: Probably not before. Do you think that he would need to have pedals too? A: Definitely, for accompany congregational singing too. Definitely need pedals. V: Mmm-mmm. So Principles, 8’, 4’, 2’, Mixture, before Mixture you could have a fifth, 2 2/3, and 16’ principle, if it’s a big organ. Flute, if it’s a smaller instrument. And similar things in the pedals, I suppose; 16’, 8’, even 4’, right? And if you have Mixture in the pedals, you might add the Posaune in the bass, like a 16’ reed in the pedals. A: Yes, it’s nice. I like Posaune. V: Why? A: It’s my favorite reed stop. V: It’s so low and rumbling, and very scary to listen to. A: But I like it more than the trumpet 8’. V: It gives gravity. A: True. But in order to play the Posaune in the pedal you need to make sure you will not do a mistake in the pedal line. Otherwise everybody will notice them. V: You might have some things in common with Johann Adam Reincken. Because remember in Katharinen Kirche, in Hamburg, he advocated and added 32’ Posaune in the pedals. A: Wow! V: For more gravity. Or was it the Principle, I don’t know, but,,, A: Maybe not the Posaune. V: But it was definitely 32’ stop. Because he wanted more gravitas as he wrote, as he said maybe. So that’s suggestions about registration. Would do you think should go first; modulation, or improvisation when you are developing your techniques? A: I think modulation. V: Modulation, right? A: And even I will go a little bit back. Before modulation you have to be able to play cadence very well, cadences and sequences. Then after these two steps, then modulations come. Because modulation skill is a little bit more advanced skill than playing sequence or playing cadences. V: Would C.K. and other people benefit from your Youtube channel? A: Yes. You could try to play some of my sequences and cadences and some modulations too. V: Mmm-hmm. That was really helpful that you did. A: Because when you play sequences you get acquainted with various keys very well. Then it doesn’t matter for you if you are playing in C Major or in C# Major. I mean you feel equally well in each key. And after that you can start to modulate from one key to another key. V: I have a question, Ausra. A: Yes. V: How did you feel about making those videos? At the time? It was like a couple of years ago, probably. A: Yes. Well? I felt, interesting. V: Interesting or interested? A: Interesting. V: Uh-huh. A: Because usually that’s what my students do for me. I sit and listen and count the mistakes and make suggestions for them. And briefly sequences, cadences and modulations for me. And at that time I felt like a student myself. I had to play and also to talk at the same time. V: Do any of your students ever told you about, that they watched your videos? A: No. I don’t think they are interested in harmony. V: Uh-huh. But you could say them, ‘oh, guys, if you struggle with cadences and sequences and modulations, watch my Youtube channel’. A: Well... V: Some of them might, you know. A: Some of them also might. Some of them might not. V: Mmm-hmm. A: So but, it was for me, I don’t know, a hundred time easier for myself to play it, than to listen they playing. Because it’s quite annoying when we are playing very slowly and making mistakes over and over again, and come unprepared. V: I think our Secrets of Organ Playing students would play better. Because they have motivation, at least. A: It’s very important. V: Right? A: To have motivation. V: Do you have motivation to continue making those videos in the future? A: Yes, but probably not this year. I have too many,,, V: Too many classes to teach. A: Classes. V: Plus you additionally, have harmony classes with National Association of Organists. A: That’s right. V: I bet they will find them useful too. Okay, so guys, keep listening to our conversations, keep looking forward to new installments, and maybe, when Ausra is less busy, she can also create something new for you in terms of harmony too. And in terms of improvisation for C.K., if he wants to play in church, I think the most helpful thing to do would be improvising hymn introductions first. Right Ausra? A: Yes. V: In variety of ways. Could be simply re-harmonizing the hymn, or playing in two parts without the middle parts, tenor and alto. Could be a fuguette, taking the first phrase and treating it fugally, in three or four parts. A: Could be toccata. V: Toccata! A: Yes. Playing like melody in the bass. V: Uh-huh. A: Hymn melody for example. Toccata based on a hymn tune. V: But that’s for probably postlude, more. A: Yes. V: It’s very useful to impress your congregation. A: And do some fast figurations with hands. I think it would sound nice. V: So guys, if you feel that your congregation doesn’t support you enough or doesn’t clap after, doesn’t applaud after your playing churches, church service, just play a toccata, hymn improvisation based on toccata figuration, and we can personally guarantee that you will get some applause after that. A: Yes. Usually people like loud and fast. V: Right. And please, write after you do, write your feedback, how it was, and how congregation reacted. It’s really interesting to discuss that, and maybe you will get a lesson or two from that in the future, for your future performances too. A: Yes. V: Okay. Please keep sending us your questions. We love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice... A: Miracles happen!

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 309 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Michael and he writes: "Hi Vidas, You're very welcome! I very much enjoy your music scores, and I intend to purchase more in the future. Thank you for making them available for purchase! They are all excellent works. I was hoping you and Ausra might consider discussing the following organ history subjects in future podcasts: 1. When was the organ introduced into the Christian liturgy? Where were the first church organs installed (e.g. in which regions of Europe or Western Asia, etc)? How did the earliest organists serve in the context of the liturgy? Were the service-playing responsibilities quite different from that of a parish organist today? What was the medieval (pre-Tridentine) mass like? 2. Historical tunings/temperaments: Pythagorean tuning, Mean-tone temperament, the "well-temperaments," etc. When and were where these tunings were used? 3. Compositional practices/features of organ music prior to 18th century? Who were the key composers in the development of organ music composition from the medieval period to the 17th century? Thank you for your very helpful and informative podcast and blog posts! Most sincerely, Michael" V: What do you think for starters, Ausra? A: Well I thought how many dissertations one could defend on these subjects. V: This is like an outline of at least several organ literature classes and workshops too. Organ literature, organ building, what else? Organ composition probably, history of organ composition. So these are all questions that Michael is very interested and we really appreciate the broadness of these topics. A: I think we might have to divide them somehow. V: Obviously it’s impossible to cover even in a detailed manner at least a few of them in one sitting. Even in one sitting it would be impossible to do detailed analysis of one question because for example when Michael asks about how did the earliest organist serve in the context of the liturgy we could talk for hours about that. Or what was the medieval mass like? These are very broad questions. For this conversation what would you like to start with Ausra? A: Maybe from the beginning. V: When was the organ introduced into the Christian liturgy? This is a riddle. A: This is a riddle. I don’t think anybody has solved it yet. But, from what we know now, that organ came to the monasteries first. V: Remember that book by Peter Williams. He wrote many books but I’m thinking that actually any book that he wrote about the history of the organ would deal with that question because he kind of specializes in that history of the organ art and I think that I read about a gift by the Byzantine emperor to the father of Charles the Great, Pepin the Short was his name, in the year of 767 I think and the history was that he gave a gift of organ, probably positiv organ, and Pepin the Short was so impressed that he asked his monks to dissect how this organ was constructed and build more of them for him. A: I don’t think that right at the beginning they were used for liturgical purposes. V: So that’s into the western part of Europe from the Byzantine empire. If we’re talking about ages before that how did organ come into the Christian liturgy in general, let’s say into Byzantine liturgy, we don’t know for sure obviously, but we might guess it was like maybe 1000 years ago. A: I think naturally because you know Byzantine culture took over classical tradition, Greek and roman empire, so that’s how we inherited the organ in general. But I’m not sure that we used much also organ in the liturgy because look at the Orthodox church now. We don’t use instrumental accompaniment at all or instrumental music in the liturgy. Basically we just sing. Voice is the main instrument. V: I guess it was introduced into the western tradition more deeply about 1000 years ago and they have a theory that it was because organ represented the harmony of the universe in some way, maybe because each pipe was like a human being and together like in a choir they make harmony, those pipes. It’s a complicated theory. A: Yes, it is. And in general I think that organ was started to use more often when liturgy needed it because in the early time in Catholic churches too basically Gregorian chant was sung and it didn’t need much instrumental support at that time. V: Umm-hmm. And I guess when we are talking about early Christian liturgy organ was like more of a signal instrument at first. If you look at paintings or representations of early organs in frescoes, medieval paintings, they are small, they sit on a swallows nest on one column and they are very narrow. I think in that case they didn’t have stop handles. They didn’t have possibility to change organ colors. What was this term called? Blockwerk, right? A: Yes, it was Blockwerk. And I think in Blockwerk you could not use separate organ stops, everything would sound together. And only in the Renaissance I believe this big discovery or organ mechanic was made where you could have separate stops. V: So if you play on the medieval organ the sound would be like a big, big organ, principal chorus sound with powerful mixtures up to 25 ranks or something like that. A: And I think with Blockwerk, especially if it was portable it was used during processionals. V: Right. Do you remember the story of how organ came into Lithuania? A: Yes, I remember Ulrich von Jungingen. V: Grand Master of Teutonic Order. A: Yes he gave us a present to our Grand Duke Vytautas Magnus' wife. Organ and clavichord too, not only organ. V: Umm-hmm. Clavichord was a novelty at this time and he gave also a portative organ to Vytautas' wife Ona. And it was usual to exchange gifts. I would presume Vytautas would also give gifts on other occasions when he visited Teutonic order too. But remember it was in the year of 1408, two years before the battle of Grunwald in 1410. In the current territory of Poland joined forces of Poland, Lithuania and other united alliances defeated Teutonic order. So maybe Teutonic Grand Master Ulrich von Jungingen was trying to avoid this battle. A: Probably organ was too small to avoid this big war. V: Right. And those battles actually were part of the expansion politics of Christianity, at least officially. A: True, true. But it’s funny because our country was already Christian country by this time. It means that all those wars were just somebody’s cover up for basically expanding the territory and taking of money and treasures. V: Although they were probably officially declared as crusades but… A: There were no pagans at that time in Europe anymore so… V: Umm-hmm. They have little to do with religion literally if were talking about religion expansion of Christianity. More about politics. A: Yes, not let’s go back to the organ. And I think that’s the end of middle ages and renaissance was sort of a very good period for organ to develop and I think it advanced a lot. But still if you look at different countries I believe that basically reformation, especially Luther’s’ tradition gave the biggest inspiration for organ to develop and expand especially if we’re talking about pedal section because if you would take catholic countries such as Italy or France in the early ages the pedal is very undeveloped. V: Umm-hmm. A: But if you look at Northern Germany, look at those big huge pedal towers. Because Catholics at that time didn’t sing I think altogether. And liturgy was more for clergy and people would just observe things what was happening because everything was in Latin and nobody could understand anything so we could just watch. But in Lutheran tradition people became an important part of liturgy itself and congregational singing began to develop and that’s why we needed these big organs, to support congregational singing. V: And still today in Lithuania congregational singing is not a very strong part of the worship because of that Catholic tradition of Gregorian chant. OK guys, I hope this was useful to you for closing our conversation I think I might add to Michael that if these questions are interesting to him, what he could do, when he’s reading books about that, obviously our Podcasts cannot be the only source for information on such subjects, right. You have to dig deeper but when you dig deeper, and for everybody who digs deeper I think it’s wonderful to a little bit document your discoveries and maybe do it online in the form of little blog or on social media you could have a public record of your discoveries and also you could leave a trace online for other people to follow when they are interested in these subjects in the future. A: Yes, I think it would be very helpful for others. V: I know Michael has SoundCloud channel too so he could do a Podcast like we are doing but maybe more about organ history side about what he is studying with. He could do it in written form as well. Alright, wonderful questions brought topics for discussion in the future and please send us more of your feedback and stories. We love helping you grow. And remember when you practice… A: Miracles happen.

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 308 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Jaco, and he writes: Dear Vidas Thank you for your daily posts - it is really an inspiration! I really like Bach's Toccata in d (Dorian). It is a piece that feels like it has perpetual motion - something always keeps moving in it. It is quite a difficult piece to master, but I decided to learn it. The edition I am playing from is the new 2012 urtext Breitkopf & Hartel edition. It indicates a trill in measure 29 on the top e in the RH (please see below). However, it does not indicate when this trill should stop. The note is held on for another 2 measures. When should that trill stop? I don't know how to play the RH in measure 30 if trill has to continue, since a lower voice starts with that hand halfway through measure 30. Another question - I know the piece has to be played articulate legato. However, it does sound quite nice if the first 2 semiquavers on the motive on beat 1 and 3 are slurred (played legato). I have heard it on some recordings as well. Would this be considered acceptable to do? Looking forward to your reply! Kind regards Jaco V: So, in measure 30, on the second half of that measure right hand, 16th notes enter. And, if you were to continue this trill, it would be impossible to play double-16th notes in the left hand in parallel 6ths, Ausra. What do you think? A: Well, unless you would use the 5th and 4th finger to make the trill. V: Oh, that’s...that’s torture! A: It is! Or maybe you could play those 16th notes with your left hand. V: But you see, can many people play double-parallel-6ths in that tempo? In the really fast tempo? A: I don’t think so. But it would be so nice, you know, to have that trill until the measure 31 where you have those chords in a cadence. V: At least in the middle of 30, when the right hand enters with 16ths, too. But, you say you would try to play it with the left hand, right? Both voices that move in 16th notes. A: That’s one of the possibilities. V: Technically, it could be done, A: Yes, it could be done… V: Because the distance between those two parts is not more than one octave. So, technically, if you are good with your left hand, it could be done, but, in reality, not too many people can do this. Yes? So then, you sacrifice something. A: Well, yes, but in general, while using the sense of your mind, I think you would stop playing that trill when the second voice in the right hand enters. V: That’s what I’m thinking, too. A: In the middle of the measure 30. V: That’s right. A: Is it measure 30? Yes. V: Okay, so that’s our solution, and I think Jaco feels that way, too, because it’s impossible, really, to play perfectly the long trill and both voices in the left hand, unless you are a virtuoso. A: I think that’s what Bach meant, to play the trill until the 16ths enter in the right hand. V: What about playing a short trill, just like four or five notes? A: I don’t think it will work in this piece. Could you go back to the score, please? ...because, as Jaco already said, it’s perpetual motion in this piece, and this starts right away with both hands, and pedal comes in here, and then you have the trill in the right hand, and if you want to play it or you do it very short, then I don’t think it will do good for that sense of motoric movement. V: I just have to double-check the older edition from the 19th century, from 1861, Bach-Gesellschaft-Ausgabe. What does it say? If it’s a long trill or a short trill….it might be something different. And sometimes 19th century solutions are better than 21st century solutions. A: Well, it’s good to know more ways than one, you know? And to check more editions. V: Okay. Let’s see...we’re looking now, and trying to find… this trill is in parentheses in Bach-Gesellschaft-Ausgabe on which our version with fingering and pedaling is based! So you could play it, or you could not play it, I guess. A: I would play it, because if you would just hold that long note… V: True.. So then, Jaco has another question. He writes: “I know the piece has to be played articulate legato. However, it does sound quite nice if the first two semiquavers on the motive on beat one and three are slurred—played legato. I have heard it on some recordings as well. Would this be considered acceptable to do?” That’s a very fast tempo, and… A: It is! V: in such a fast tempo, A: It might sound legato. V: Right. A: Actually, I don’t believe that somebody on purpose played those two semiquavers legato. I think it’s just a feeling you get when it’s played in a fast tempo. And because you have to emphasize the strong beat, that’s why it sounds legato, too. V: Because you make the first note longer. A: Longer. That’s right. But, somehow to try on purpose to play it legato, I wouldn’t do it. V: Plus maybe the acoustics environment will make it sound legato. A: True. V: But the organist probably would still play with articulation. It’s different from what the organist does and what the listeners hear A: That’s right. V: Interesting piece! A: Because, if you play legato on purpose, then you might get a mess, or your listeners might hear a mess. V: I played this piece many years ago, when I was still a student, and I struggled with playing it in an even manner, because it’s a motoric piece, like a toccata, and after a while, after a few pages, it gets quite difficult, just like in Vivaldi-Bach Concerto, D minor, the last movement. A: And it’s like C minor Prelude from Well Tempered Clavier, the first volume also very motoric. V: Yes. Organists have to develop good patience while working on this piece, otherwise, we can lose a sense of meter! A: True, and I think it would be a crucial point in a toccata if you would lose your sense of motion—that sense of meter. Your toccata would be lost to it. V: I wonder how Jaco is practicing the fugue. He doesn’t say anything. Because, the fugue is, I think, more complex! A: True! V: With so much canonic motion. A: Yes, because the toccata, there, is not much of polyphonic devices, but fugue is another thing… V: And, sometimes the fingering is tricky. That’s why we made fingering and pedaling for both toccata and fugue, of D Dorian, and hopefully people can practice efficiently using our score, too. Okay guys, thank you, Jaco, for this wonderful question, and others, please keep sending us your feedback and your stories. We love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice, A: Miracles happen!

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 307, of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Tamara. And she writes: Hello Vidas– I have been following your Secrets of Organ Playing emails—very helpful, thank you! Do you recommend total legato for hymn playing in any situation? I did learn and follow the 4 ways to render a hymn in the Ritchie book (Chapter 7). It seems that the best, most efficient hymn playing is balance of legato and articulation, distributed among the SATB parts. Thank you. Tamara V: Mmm. That’s a very specific question, Ausra. A: Yes, it is. V: And the way I remember Dr. Ritchie teaches is, and Quentin Faulkner too—is if the hymn is created after 1800’s, then you play it legato. And if it’s an earlier hymn then your articulate. Very simple, or not? A: Yes. Sounds about true, but you always need to look at the specific keys and the specific hymn too. Because there are sometimes later, composed hymns that you also need to articulate. V: Right. It could be like Neo–classical style. A: That’s right. And there are also specific hymns that might be created, at least the melody might be created earlier, for example, based on Gregorian chant, that you want to play legato for example because it sounds better that way. V: Really? A: Really. V: Mmmm. So Gregorian chant sounds better with less articulation, you think. A: Yes. V: Oh. Interesting. A: I think so. At least for my ear. V: If I create, for example, a hymn tune today, but it’s in baroque style, or ancient style, this too should be played probably with articulation, or not? Because it’s 21st Century. A: It depends on the style. V: If the style is earlier than,,, How would you play my music, Ausra? Would you play my music at all? A: Which one? V: (Laughs). A: I don’t think so, but,,, V: Nobody wants to play my music. Not even Ausra. Okay, guys. Let’s stop for a second to cry, and then after we done crying, we’ll continue. Okay! I’m done crying. Now, Tamara says that the “most efficient hymn playing is balance of legato and articulation, distributed among [the] SATB parts”. What do you think she means by that, Ausra? A: I think that what she says? V: Balance of legato and articulation? A: Maybe by that she means that you play, I don’t know, soprano legato and you articulate other voices, or maybe that you take breaks, articulate between phrases. I’m not sure. V: Or maybe, it’s articulate legato. You know,,, A: Oh. Could be. V: Mix between legato and non-legato. A: But in general, I always look actually, when I take a hymn, I look not at when it was written. I look at the musical structure. I look on the particular organ that they had to play that hymn. I look in the space if it’s reverberant, or if it’s dry. I’m thinking if I will be singing it solo or congregation will sing it too. Because in general, the more reverberant room is, the more articulate you have. Even if a hymn is written legato, you will have to do some articulation between phrases. Because if people are singing, the need to take a breath. Music needs to breathe. V: The monster never breathes. Who said that? Stravinsky, I think, about organ. A: Well so maybe... V: Stravinsky didn’t know that articulate legato playing style at that time. A: Could be. I think it was part forgotten during his lifetime. So... V: Mmm-hmm. So let’s make organ breathe, right, guys? Let’s make it actually sing. Without breathing there is no singing, right? You have to sing yourself. Imagine you are singing with the congregation. That’s the easiest thing. You don’t have to sing soprano part, you can sing middle voices, or the bass. That’s up to you. But if you sing, you naturally have to breathe. A: That’s right. And of course, it also depends on the tempo that you are playing the hymn to. The slower you play, the more breaks you have to take. V: Does it, come easily, this type of articulation or not, Ausra, for people, or for you? Let’s say for you personally. Do you remember your first attempts at hymn playing? How did you feel? A: Well, when I just started to play hymns at church, I actually didn’t think so much about either to play them legato or non–legato. V: Mmm-hmm. A: I had other concerns at that time. V: Such as? A: How do not miss the place in the mass where the hymn should sound; how don’t miss pedal keys, and don’t mess them up. And all that liturgical struggle. V: Will the people complain to the priest after your playing? A: No. Well... V: (Laughs). A: There was one lady who thought that especially you play too fast. V: Mmm-mmm. A: Because... V: You mean myself? Vidas? A: Yes. And I’m playing a little bit better because I’m playing a little bit slower. But still not slow enough for them, because he wanted to drag the hymns, and to slow them down as much as possible. That way mass would never end. V: This was one of my last church service playings in that church. A: Yes. That’s right. V: (Laughs). Yes. I guess in every congregation you have people like that—complaining and going to the priest or pastor, and telling them how things should be around there. Because they know better. A: True. V: So you say you didn’t think about articulation at the beginning? A: Yes. At that time, yes, I didn’t think about it because I had much more things to think about. V: For me, I don’t remember, maybe in America I started to think about articulating hymns, more, than in Europe. Is the same for you? A: Yes. True. V: Everything changed when we went to America, somehow. We started thinking differently. Maybe teaching style was different, right, and more clear, and more specific, and things were explained to us in a way that, at that age and stage of our development, we could understand. Of course we already had masters degree from Lithuania, so we weren’t beginners there, but it was good to do a second masters degree, and doctoral degree after that too. Don’t you think? A: Yes. V: Okay, guys. Try to experiment with many playing styles when you encounter hymn playing. Because every century requires its own rendering of legato or articulation. Don’t you think, Ausra? A: Yes. That’s right. V: Mmm-hmm. So, thank you guys for listening, for sending these thoughtful questions. We think that when you apply our, sometimes advice, sometimes feedback, sometimes just experiences to your playing, for some people it’s really helpful. Not for everyone, right? Because some people have their own opinions and that’s okay. Because we also have our own opinions about things. And Ausra’s opinions sometimes are different from my opinion, right, Ausra? A: Yes. V: Would you, Ausra, like that my opinion would be the same, like yours? A: I can’t imagine that! V: (Laughs). What about me? Do you think I would love that? A: I don’t think so. V: We like to argue. Then we wouldn’t have anything to argue about. A: Yes. We love to fight. V: Yes. At least in drawings. A: That’s right. V: Okay. Please send us more of your questions. We love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice... A: Miracles happen!

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

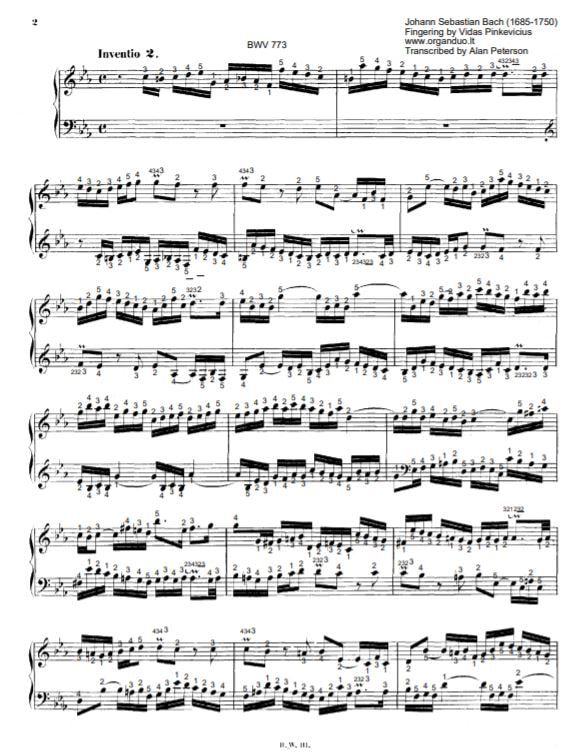

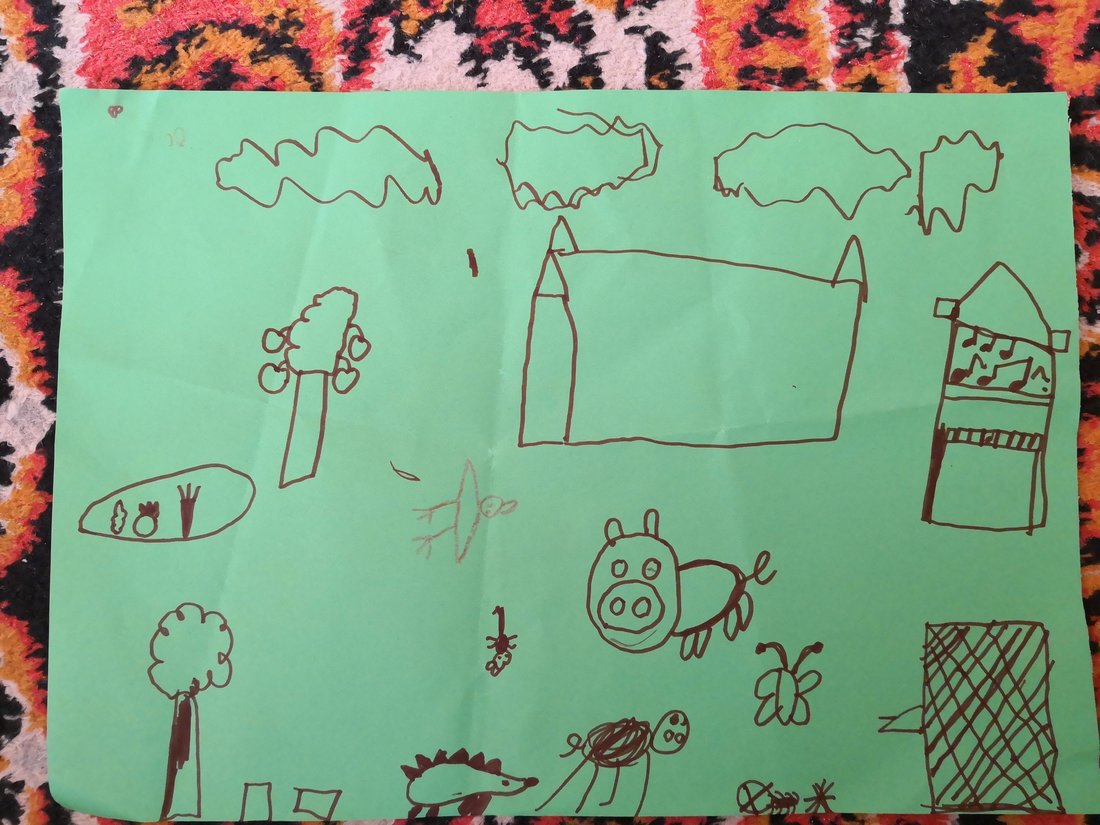

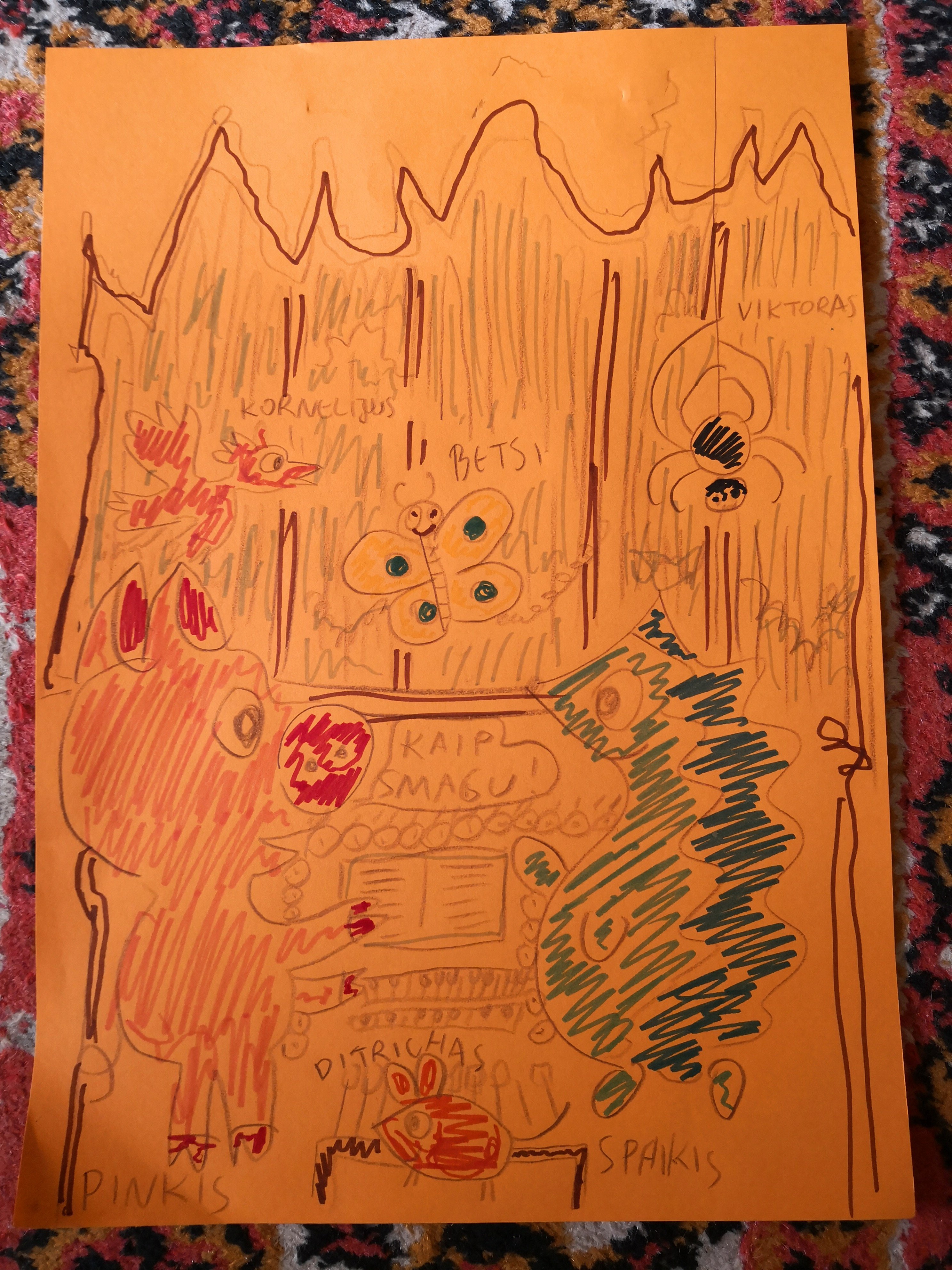

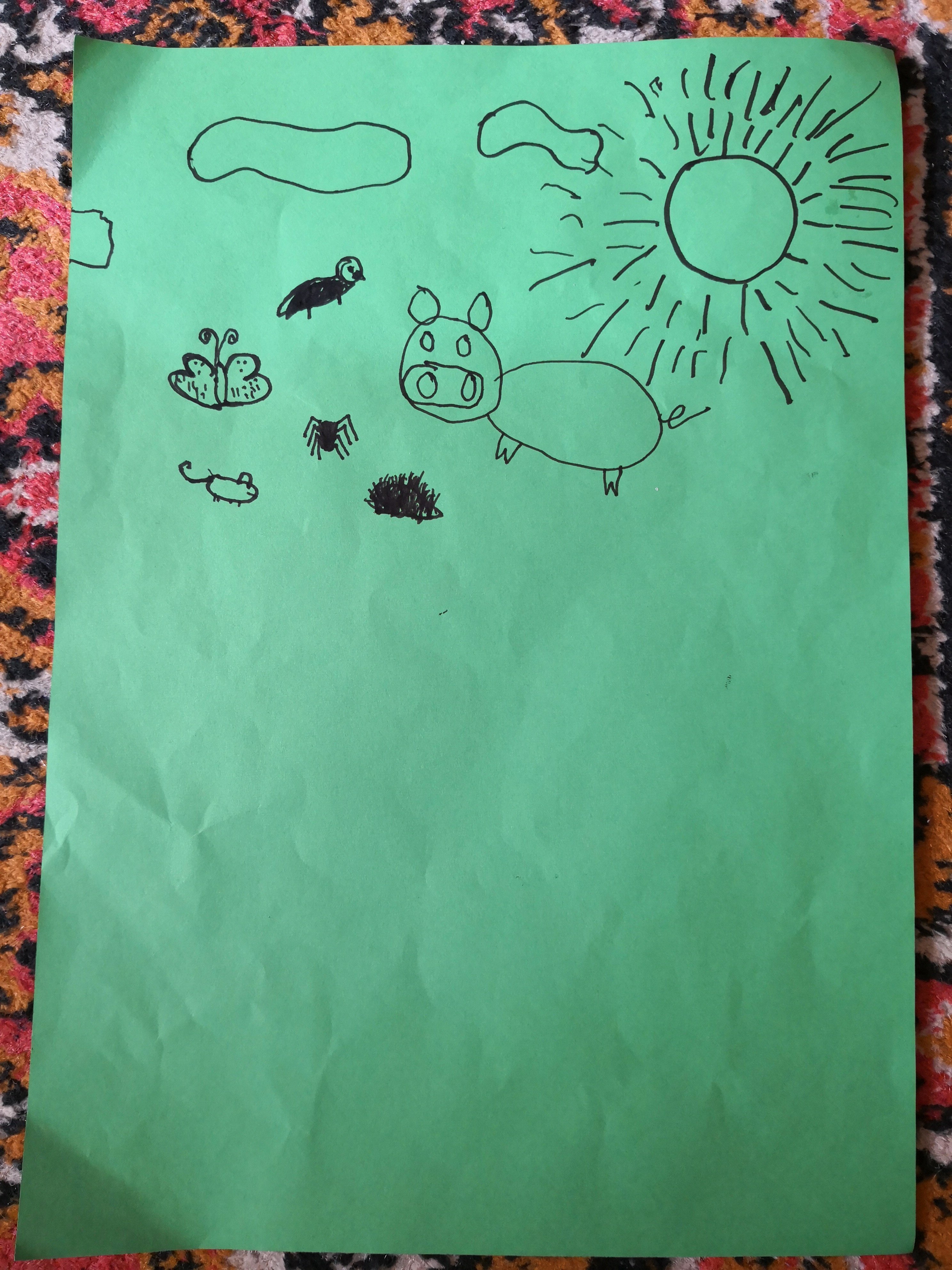

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 306 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Jack and he writes: “Hello Vidas, I practice every day for 1 or 2 hours, sometimes even more. But I make slow progress on e.g. Bach level 1 course. Probably due to my age (71) and the fact that I didn't play for almost 30 years. But the good point is that I ENJOY the practicing now, thanks to your inspiring learning materials. Rgds, Jack” V: This is really nice to hear when senior person is trying to reacquaint himself with the organ while being absent away from the keyboard for decades. A: That’s right. V: Right? How old is your dad for example. A: Seventy-six. V: Seventy-six. We certainly have students like that and older in their eighties I think too. The oldest one was 89 maybe or 91, basically pushing towards 90 and still learning. That’s the most fascinating thing to me while many people just watch TV all day at that age. People like Jack tries to improve himself every day. Of course it’s not easy at this age and Bach Organ Mastery Level 1 course is not really beginners course. Eight Preludes and Fugues are not the easiest pieces that he wrote or his students wrote. What would you have to say to Jack? A: That he is doing an excellent job actually. Just doing it is already wonderful. V: At this age you don’t have to press yourself too much, you don’t have to worry about other things, how other people think about you, about your future career, where this might lead you or not, is it worth your time or not, you just play for your own enjoyment. If you want a more thrilling experience you could actually after learning a piece or two go find a local church and play for the prelude or postlude just for experience and playing in public but it’s not required. You could simply play it for your friends and family. That would be amazing enjoyment for them. A: Yes, and I think this age, 65 plus ten years, is when people retire usually and they have more time so they can practice organ. V: It’s like hobby, right? A: Yes. V: But this hobby started late in life, right? Is it good to take up something new at this stage? A: I think yes and I think Jack used to play because he only hadn’t played now for thirty years. V: Do you imagine yourself being at seventy or more and taking up some new things learn, if you are living that long. A: Well yes, if I am living that’s a very good question. I don’t think I will be living by seventy but… V: If you do. A: Yes, why not? V: Why not (laughs) if you say so. If that’s what you want dear. A: But you know I already play, I already draw, what else could I do? Do some sports at that age maybe? V: Do some sports, yes. Because you know stretching is important at this level, walking is important, moving basically. A: But I’m walking now. Not right now but in these days. V: (laughs) Maybe something that you even haven’t thought about, something entirely different like jumping out of the airplane with a parachute. A: Oh no, I’m afraid of heights. And I can swim so I cannot learn swimming at that age. Maybe do some ice skating. V: Ice skating, yes. What about skiing? A: I don’t know, maybe. V: Cross country skiing. A: Winters are getting so mild we don’t get enough snow. V: I’ll try to introduce you to skiing when we go to Alps next March if there is any snow left. We’ll be playing at the organ festival there in the French Alps and it will be very fascinating to see the mountains from up close. A: Thanks for warning me about your plans, maybe I can not go, find an excuse, and leave you alone to perform. V: That would be a sad choice I think. But we can work something out I think. I’m not fond of skiing myself. I just like watching other people ski. A: Usually people who like to watch sports don’t like to take any and do it themselves. V: What did we do last Wednesday, do you remember? A: Oh, going to Leliunai to perform? V: Yes. What did you think about that experience? A: It was nice. I have never played for kids so young in age. V: There were kindergarten level kids and elementary school children too. About twenty-eight total of them plus several adult teachers and all of them were gathering around the beginning of twentieth century organ in this little town of Leliunai and we were supposed to do organ demonstration for them. Ausra was supposed to play for them and I was supposed to talk and Ausra played organ music. What did you play? A: Bach, Krebs, Mendelssohn, Franck, and Lefebure-Wely. V: Exciting pieces, at least for adults. And then I talked, I told them a fairy tale, like a story about piglet Pinky and hedgehog Spiky and their friends building pipe organ and that was my way of introducing the kids to the organ because through story we could remember better things. And what else they did? Oh, they drew the scenes from the story with George and the organ with animals too. Also they were more focused this way. A: Yes. There was one small boy that stood behind me all the time and looked at the score, at my hands, through the entire performance. V: Maybe that’s a future organist. A: Could be, I thought about it too. V: And then after Ausra played the last piece we invited everybody to try out the instrument for a few moments, not for a long time because twenty-eight kids, that’s a lot and we only had ten minutes left before we had to go to eat lunch. And the priest was nice because he gave all the kids lollypops. A: Even we got one for each. V: We are saving them for Saturdays. A: That’s right. So Jack, I think you are on the right track because progress even for young people doesn’t come easily so just keep practicing. The most important thing is that you are enjoying it. V: If you master just four measures per day that’s beautiful progress I think and you repeat previously mastered measures too your progress grows stronger and stronger each day. Thanks guys, this was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: Please send us more of your questions. We love helping you grow and remember when you practice… A: Miracles happen. SOPP305: I enjoyed the Bach organ tour but the big surprise was how sharp most of the organs were10/15/2018

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 305 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Alan, and he writes: Vidas, we are back from our travels. I enjoyed the Bach organ tour but the big surprise was how sharp most of the organs were. It wreaked havoc with my absolute pitch and made it very difficult to play. It didn't get easier, but I didn't push it too much as there were others waiting for a chance to play the organs. For something else to do I took measurements of the temperament octaves of many of the organs in order to make some comparisons. A podcast on coping with different pitches would be good. V: So, Alan is already introduced to historical temperaments, right? A: Yes. V: This is nice. A: True. V: Was it difficult for you to adjust, Ausra, when you first encountered different pitch levels in the tuning of different organs? A: Well, a little bit, yes, but I wouldn’t complain about it, actually, I liked it so much. V: What was the first organ that was different from A440 that you played or heard? A: Actually it was a small organ built by John Brombaugh in Gothenburg, Sweden, in Haga Church. That was my first organ. V: So, probably the same for me. A: That’s right, and because it has split keys, I remember that you could not figure out which are flats and which are sharps, and I had to do it. And somehow, I did it fine. You just need to listen, really. V: On that organ, I chose E major Preludium by Buxtehude with four sharps—very stupid idea. A: Well, at that time, we simply didn’t have any idea what the historical temperaments are. V: And what did you play there? A: Well, I played, I think, Preludium in G minor. V: Much better choice! A: Yes. It was better. V: With two flats. Anyway, so the tuning was quarter-comma meantone, and the pitch level was A=465, I think. A: Yes. V: Half step higher. A: Yes. And, you know, a couple remarks about “absolute pitch,” as Alan called it, or I would call it, “perfect pitch.” It’s usually not a pitch that is related to this, it’s usually your memory. Your musical memory. You simply memorize everything at A440. V: And the reason I asked him if it got easier when he touched the keyboard and started to play is because for me, somehow, it became easier. I forgot somehow, but maybe I spent more time than Alan on the organ. A: Well, let’s say, I used to have to play sometimes, even during the same recital, on three different instruments. I remember accompanying at Eastern Michigan University, for example, and I had to play on the organ, on the harpsichord, and on the piano. That was hard work. And I remember in one recital, I had to do Sweelinck’s Fantasia Chromatica on the harpsichord, which was tuned quarter-comma meantone, and then I played on the organ Bach/Vivaldi Concertos, which was tuned in A440. And for me, it was really difficult to go through the first page, and after that it was ok. V: You mean of Bach? A: Yes. V: Because you played Sweelinck first, and adjusted, got used to it, and then suddenly had to switch to Bach—to the modern organ. A: Yes. But you know, after working for a while with historical tuning, when you go back to 440, you see that it’s really harsh sounding. That there are no pure intervals, and everything is so, so out of tune, actually! V: Did you notice that piano sounds milder with equal temperament than the organ, actually? A: True, because I think the pipe sound is so much more prominent than the piano. V: And the sound doesn’t fade. A: True. V: So, yes, it needs some adjustments and some experience with different instruments, but each new instrument gives you new perspective—new experience, right? A: True, and I think if you are getting in trouble adjusting to a historical tuning, I think working on the 440 instrument, you need to transpose more often, to play the same pieces in different keys. V: Mhm, why? A: Then it will be easier for you to adjust. V: Oh, transpose… we need to ask Alan if he practices transposition then! A: True. V: At some point, I remember making a few videos of the same piece in different keys—a Two Part Invention by Bach in C major. I played it in C major, in F major, and in G major, recorded on YouTube, and I transposed it into all the other major keys when I practiced, but didn't record it yet. So, it really helps to do this regularly. A: Well, and another thing, if you want to adjust to historical tunings, if you have access to a harpsichord, then it’s easier to do, because harpsichord is an instrument which you can tune in different tuning systems very easily, so you could practice. V: Or a clavichord. A: Or a clavichord. I think it’s easier to access a harpsichord, probably, than a clavichord. V: Right. A: But I think it’s all a mental thing. V: But I think Alan seems to have enjoyed this experience, right? But when he started to play that it was difficult, right? Or when other people played, he couldn’t listen to the original keys. I myself remember in Sweden, back in 2000, in Gothenburg, so other people played C major. I remember Bill Porter played 545 Preludium and Fugue in C major by Bach. This was one of… A: In Örgryte V: ...In Örgryte New Church one the first times I heard this piece, actually. And he announced that this piece will be in C major. And I prepared myself in C major, you know, my “perfect pitch system” based on 440, and he started to play, and it sounded D flat major, and the whole time, while being downstairs, I was mentally really struggling to think, “What is happening, and what is he actually playing?” Not, “What I’m hearing,” but, “What is he playing?” But again, when I started to play this on organ on another occasion, not right away, but after a few minutes, I think, it became easier. A: Yes, for me, it takes about one page to adjust. V: Right. So, Ausra, do you recommend people trying out different historical instruments and going on tours, like Alan did? A: Yes, I think it broadens your perspectives in general. I think it’s a wonderful experience. V: Tuning and pitches is just one side of the story. Another could be adjusting to the touch, adjusting to the bench height, or to the distance of the manuals when you have to reach the top manual and it’s very far from you… A: But if we are talking about tunings and you see how different each key sounds, actually, then you understand what all those treatises about the meaning of the keys is. V: And also in many historical instruments, the layout of the stops is not vertical from top to bottom, but from right to left, or from left to right horizontally! And you have to reach very, very far from the distant stop handles, and that makes it very difficult sometimes, and you might wonder if they really played with assistants or made less stop changes or what! A: That’s true! And it also teaches us that when going somewhere, abroad especially, on an unfamiliar organ, you need to find out about them in advance as much as possible, so that you will be mentally prepared for it. That it wouldn’t catch you by surprise. V: Like a short octave, right? A: Yes. V: In short octave, some of the lowest semitones are missing… sharp keys are missing… no C sharp, no D sharp, and sometimes even no F sharp and G sharp. So, if you don’t know this, and you are scheduled to play a recital on some historical organ with short octave, and you are used to playing a modern organ, then you don’t know what to play in that left hand section. Therefore, if you find out in advance, you can actually practice on your own keyboard at home or in a church with approximations of the target organ. A: Usually next to the stop list of the organ, you get a compass of keys, so you could find out about it from it. V: Thank you guys, we hope this was useful to you. Enjoy your travels, and enjoy experiences on other instruments—as many as possible, because each new organ gives you a new perspective. It’s like driving a car, right Ausra? A: Yes. V: The more you drive, the better you become at adjusting to each new vehicle. Please send us more of your questions; we love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice, A: Miracles happen.

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 304, of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Jeremy. In response to my weekly questions in our Total Organist Basecamp communication channel. When I ask ‘What’s the most frustrating thing for you this week, that you’ve been struggling with’? And Jeremy wrote: Focusing. During the postlude at this mornings service, about half way through the fugue of BWV 555 bad things just started happening. I tried to bring myself back into the moment, but it took about ten measures to get back into the zone. I am trying some of the techniques you mention in your "focusing at the organ" lessons, so the fugue didn't completely fall apart. Just a few hairy moments on a piece I felt completely fine with yesterday. I will say, ten years ago I would have stopped the piece and tried to restart it somewhere, so that's a win. V: Do you know, Ausra, BWV 555 E minor Prelude and Fugue from Eight Little Preludes and Fugues collection? A: Yes, I know it. V: I think Justas from Unda Maris studio, played it last year, or not? No. He played A minor. But E minor Regina played a number of years ago. A: Yes, I know that piece. V: Mmm-hmmm. And fugue is more complex than the preludes are obviously. A: Yes, that’s true with all eight pieces in this collection. V: Mmm-mmm. When was the last time Ausra, for you, when you lost something in the middle of the piece, and you had to figure out the way to get back into the song? A: Well, I actually can’t recall that moment, right now. V: Yeah. We would better forget it. (Laughs). Therefore we block it from our memory. A: But I know now that I showed the F Major Preludes for my students and I killed the organ. V: Oh! Tell us, please, more! A: This happened this week, actually, Wednesday, and today we are talking on Saturday. So I was playing for her the F Major Preludes from the same collection—these Preludes and Fugues by J.S. Bach or Bach’s circle. And actually organ just, sound just disappeared. And there was this horrible smell—burning, burning smell. V: Mmm-hmm. V: So I just shut down the organ and called Vidas. V: And where was Vidas? A: Vidas was practicing at the big organ in the church. V: Mmm-hmm. A: So, organ engine was dead. V: It’s good to have two organs in the church; one big for me and one small for Ausra. A: Ha! V: (Laughs). Now we only have one left. A: Yes. Now we have to share, and play four hands. V: So, what was the reason later, I could continue the story, because I was also worried. I climbed the balcony of that little chapel organ. We switched off all the fuses and smelled the burning of wires and called the security and authorities of the university. And they, it was actually almost the end of the work day, and they said, ‘Okay. Wait until the morning crew comes in, tomorrow, to check’. A: And we were really scared because we thought that the fire might get started. V: Uh-huh. A: And part of the most important part of the church might burn out, so. V: Yeah, but in Lithuania sometimes in those state funded or public positions like at the university, people work, not like they work in private... A: Companies, yes. V: ...companies. They work until the end of the day and they leave. A: And nobody really cares about anything. V: Uh-huh. So it was almost the end of their working day and they said wait until the morning. So then I, I then looked into the motor room and the smell was more intense there. The blower was sort of warm, not very hot but warm, which is obviously okay because it has been working for an hour or more. And then what else? I looked for open fires signs, like smoke or something. There wasn’t any, actually. So I thought maybe it stopped. Maybe it was just like a short, short circuit. And then I would, Ausra waited, ah. Ausra went to the big organ to practice. A: Because I had another lesson to teach so I had to go somewhere else. V: And I then spent entire afternoon and part of the evening, checking that smoke in the church while Ausra was still... A: Teaching. V: ...teaching. And even while we were almost leaving the church, I went to the security guard, to the chapel one more time so that they could smell it, and maybe check it in the middle of the night again, if the smoke is,,, A: And actually I had an earlier hard last night to sleep because right in the morning I was checking all the newspapers to see if it’s on the news, and maybe the church has burned out, so. A: Mmm-hmm. A: But everything was calm. V: And in the morning I dropped Ausra to school and then walked to the church. It’s about, what, twenty minutes walk, walking down the hill. And I was going with a fast pace, and when the church was approaching, I was sort of looking for smoke or fire brigade. But luckily, it was a quiet night there. A: True. V: The first thing I did as, I didn’t climb to the organ balcony to the church with the big organ but I looked right away at the chapel where that organ which we killed yesterday was. A: Which I killed, or J.S. Bach’s F Major Prelude killed. V: Right! I didn’t think about that F Major. Maybe that’s a very dangerous piece to play. A: It is. And so now, because Jeremy is playing that E minor from the same collection, I remembered this. V: Maybe Jeremy should be careful about playing this piece in public again, right? Or check the wiring of electricity, or the motor more frequently because of this piece. (Laughs). Right? A: Well but anyway, we have to congratulate Jeremy because he survived throughout this piece, and he didn’t stop. That’s a good sign. So I think he’s really on the right track. V: Next time, I think when he is out of the zone, the process of getting of getting back into the zone will be shorter, I think for him. A: True. True. V: Because he knows how to deal with that situation already. A: Yes. V: Right? Because he says, ten years ago, he would have stopped the piece and tried to restart it somewhere. And now, it took only about ten measures. So next time maybe it will be nine measures. A: Sometimes when I practice organ pieces, I’m sort of praying that all the mistakes that might happen would happen during my practice time. Then I would know what to do. But somehow, if mistakes happen during actual performance, they are always in the other spots. V: Mmm-hmm. A: So, you never know what might happen. V: And I think about, you killed one organ, and I killed also one organ. A: In Liepaja. V: In Liepaja, yeah. The largest mechanical organ in the world. A: Well, but you didn’t kill it. It was just some electric stuff. V: Yeah. The electric company forgot to add one phase, so it was not enough power. So now it’s okay. Umm, yes. So keep practicing guys. And I think the most important lesson here, with focusing, it just to play more in public. A: True. The more you do it, the easier it will get. V: Right. And realize that mistakes will not kill you. A: As he killed this organ. V: Right. (Laughs). Thanks guys. This was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: Please send us more of your questions. We love helping you grow. And remember, when you practice... A: Miracles happen!

Vidas: Hi guys, this is Vidas.

Ausra: And Ausra. V: Let’s start episode 303 of Secrets of Organ Playing Podcast. This question was sent by Michael and he writes: “Hi Vidas and Ausra, Thank you for your recent email, to which I am now responding late (I apologize). My dream for my organ playing is that I would like to apply for, and be admitted into, a doctoral program in Organ Performance. I am currently pursuing a master’s degree in Organ Performance. At this time, I cannot think of three hindrances to my dream, but I can think of one in particular that is proving to be, and has always proved to be, a great problem for me: I am very shy about people hearing my practicing the organ - the repetitions, making mistakes, etc., that attend the process of learning a piece of music. I am a very introverted person (which I have found is not a very common personality trait amongst organists; at least, not amongst the organists I know personally). I believe that my fear of people hearing my practicing may (at least partially) stem from the shyness and introversion, and perhaps lack of confidence in myself: worrying that people may think I am not a skilled organist if they hear how painstaking practicing can be, and sometimes how tedious the process of learning a piece of music can be (for me, at least). Even at the university, though, where I am surrounded by other graduate music students who understand exactly what I am experiencing with practicing – even there I cannot bring myself to practice on the practice organ, which makes things very difficult for me sometimes, since the practice organ is the organ on which I perform when I receive my weekly lessons, and I really need to play it regularly to continue to be accustomed to its feel and action. What I normally do is practice at the church in the late afternoon or evenings, when I know no one will be present to hear my practicing. All of this causes me to waste time, and causes me to worry needlessly. I am aware of these things, yet the fear of people hearing me practice has been one with which I have struggled since childhood. Despite the fact that I have been successful enough to work as a church organist, pursue graduate-level Organ Performance studies, and compose, I worry that the shyness and introversion, which, I believe, is the basis, or part the of the basis, of my fear of others hearing my mistakes when I practice – I worry that this will directly harm my efforts to receive an admissions offer in the competitive world of doctoral studies because perhaps my skills will not be as good as they could be if I practiced more regularly. I also worry that my shy personality may indirectly harm my efforts to be admitted into a doctoral program since my non-extroverted, non-showmanship personality (and the music I prefer to play and compose as a result of this personality) may make me seem as though I would be less successful as a graduate of the program than would another more gregarious, “outgoing” applicant, and maybe the conservatory would prefer investing in a person like that rather than me, since my appearance alone may work against me. Sadly, I have found that a very skilled but introverted organist is often (and maybe even usually) unfavorably compared to an organist who is not as skilled, but who has a very extroverted and confident personality. Thank you so much for your SoundCloud podcast and emails. I have found each podcast and email extremely helpful, informative, and enjoyable, and I am grateful for your work. Most sincerely, Michael” V: That’s a long story Ausra but has a very interesting feedback. A: Yes and he asks some things that I have never thought about. V: That organists are not usually introvert, right? A: Well actually I think that it might be wrong for you because I think many organists are extremely introverts because if you choose such an instrument you are probably an introvert because organists spend so much time alone with his or her instrument. V: Plus the instrument is hidden from the public. A: Yes in most churches so I think there are probably more introvert organists than extrovert, don’t you think so? V: Let’s think about our friends. Not all of them obviously, some of them are more outgoing than others just as in life probably. A: Well but let’s see. Let’s talk about ourselves. Have you ever done any psychological tests to determine your personality? V: Yeah, I did. A: So what about the introvert/extrovert thing? V: I don’t remember exactly those four letters about me but maybe you remember. A: Well, I remember some of it but every test that I have done showed that I am extremely introvert person. Something like eighty and more percent introvert. I never thought about that problem that somebody would hear me practicing with mistakes. Actually I don’t care about it. The more I care is that I would play well during my actual performance because then it’s real important that I would play without mistakes. So I would like to ask Michael if he feels performance anxiety during his actual performance because this is the moment when most musicians start worrying and get performance anxiety but not afraid of being heard playing with mistakes during rehearsals and another thing is that usually, especially in America, you have pretty well isolated practice rooms so if you are alone in a room nobody can hear you from outside. V: Umm-hmm. What he’s talking about is studio performance practice when he has to practice on the organ that his weekly lessons are held on, probably. Remember in Nebraska. A: Yes, I remember we had studio but I wouldn’t call it practice time. It was held once a week and everybody would play what we learned during the week. V: So maybe in his conservatory is different, maybe he doesn’t have too many isolated practice rooms. A: But how can you practice organ if somebody else is practicing something else in the same room. V: I don’t think that people are really sitting in the same room that he is playing there. A: And you know Michael, what I could you tell is that every person is busy with its own life and nobody really cares about what you are playing and how many mistakes you are making especially during your rehearsal time. V: Everyone is thinking about themselves, right. Everyone is egoist in a way. A: And everybody is thinking about their own mistakes, not yours. So I think you need not to worry about it. V: What I hear in between the lines that he’s not writing actually is that Michael might be a perfectionist who wants to do everything at the top level and if he cannot do it at the top level then he doesn’t do it at all. A: But if he wants to become a doctoral student it means he needs to practice every day and it doesn’t matter if he will practice at the university or church he needs to do it every day. V: Adapt this attitude, practice no matter what, right? It’s a professional attitude. A: True. V: You don’t have to be paid actually to be a professional. It’s the mindset that matters, right? If you skip practice because of the weather or how you feel or if you’re tired or you simply not in the mood then you are not a pro and it’s OK not to be a pro actually, I’m not blaming anybody but anyone who wants to excel in this art or any other art form has to adapt an attitude of a pro. A: Do you think it would matter much if a person who wants to become a doctoral student is extrovert or introvert. How much will this be a deciding point during your admission? V: I know what you mean, right? There is no discrimination actually. I don’t believe anybody would ask him you are introvert, no, no, we don’t accept introverts, just extroverts. It’s not that way, but if because of his shyness he practices too little and is not advancing well enough and when the time comes to show his skills during the entrance examinations then he is not ready as well as his peers are and that might be a problem. A: Yes, because if you are thinking about showing yourself bad during interview, if you are too shy to talk with people or professors, well, do all the other things good because you need to play wonderful during your audition, you need to get good recommendations and you need to have really top GPA because I remember when we were applying for doctoral studies our GPA was 4.0 so in U.S. standards that’s the highest so basically we were very competitive and then as I said excellent audition and good recommendations and then how much can the introvert harm yourself. Not too much probably. V: Not too much. You also need to write essay about your motivation. A: Not all schools require that but some do. V: You know, in the end if we summarize our advice I think from my perspective is if you want it badly enough you will overcome your shyness. If you don’t want it badly enough, if it’s not that important, if your shyness is more important, if how others see you is more important to you than how you actually see yourself then you will not overcome your shyness. A: I think this problem is more related and more applicable to teenagers. I think the teenager are at that age where it’s really important what others think. People get really worried that nobody would laugh at them and sort of not to show themselves too much to be in that crowd. But I think that at mature age and since Michael is in his Masters studies so he is already adult, we don’t have to worry so much about others and about what others think about us. Don’t you think so? V: I read a good book called “Ignore Everybody” by Hugh MacLeod, cartoonist and blogger who started his career while drawing cartoons on the back of business cards. Basically he writes down 39 key points about creativity and the most important one is “Ignore everybody.” So maybe we could conclude on that our conversation too. Ignore our advice too Michael. Thank you guys, this was Vidas. A: And Ausra. V: And remember when you practice… A: Miracles happen. A couple of days ago Ausra and I played organ demonstration in the little town called Leliunai. The listeners were 10 kindergarten kids and 18 elementary school children and a few of their teachers. This event was organized by National Association of Organists in Lithuania.

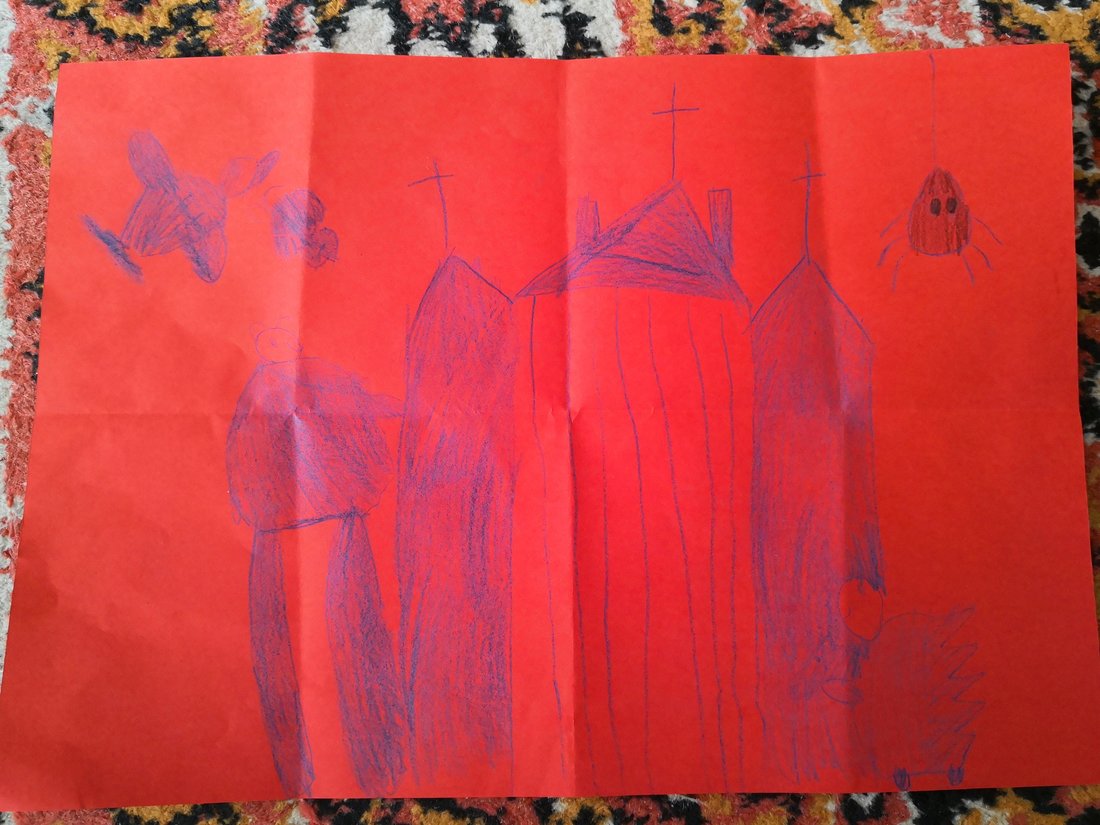

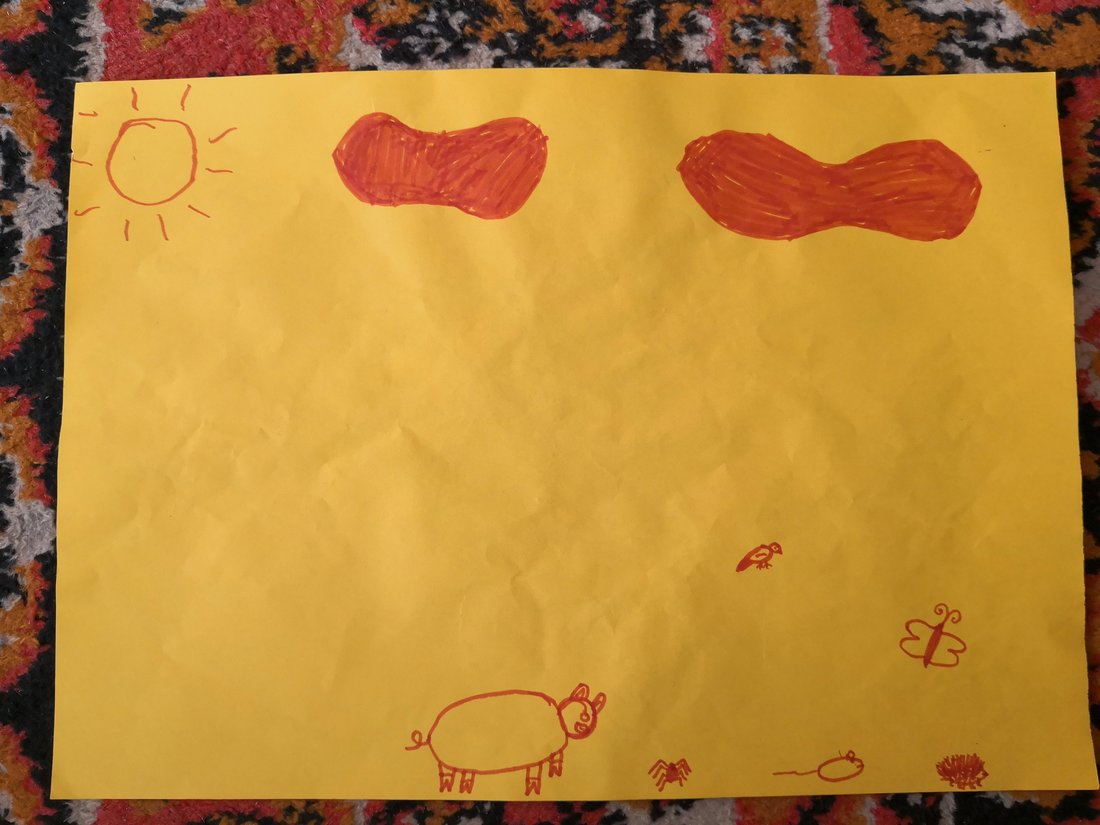

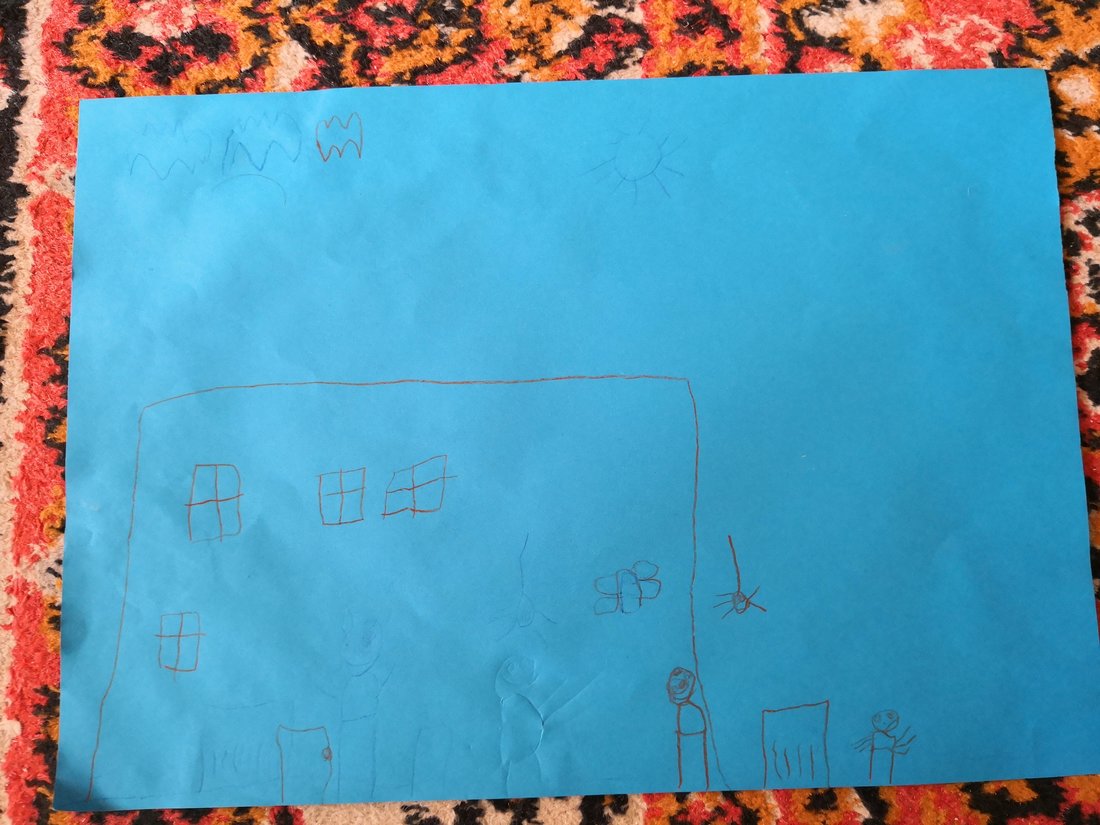

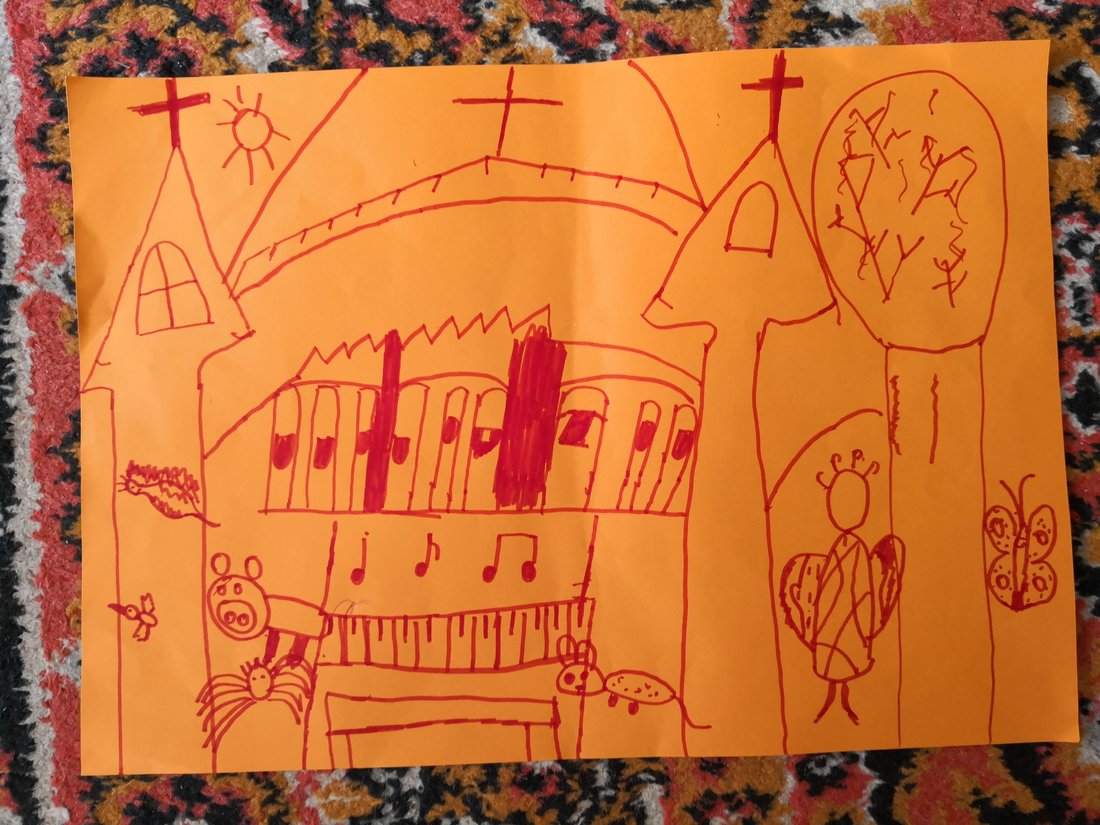

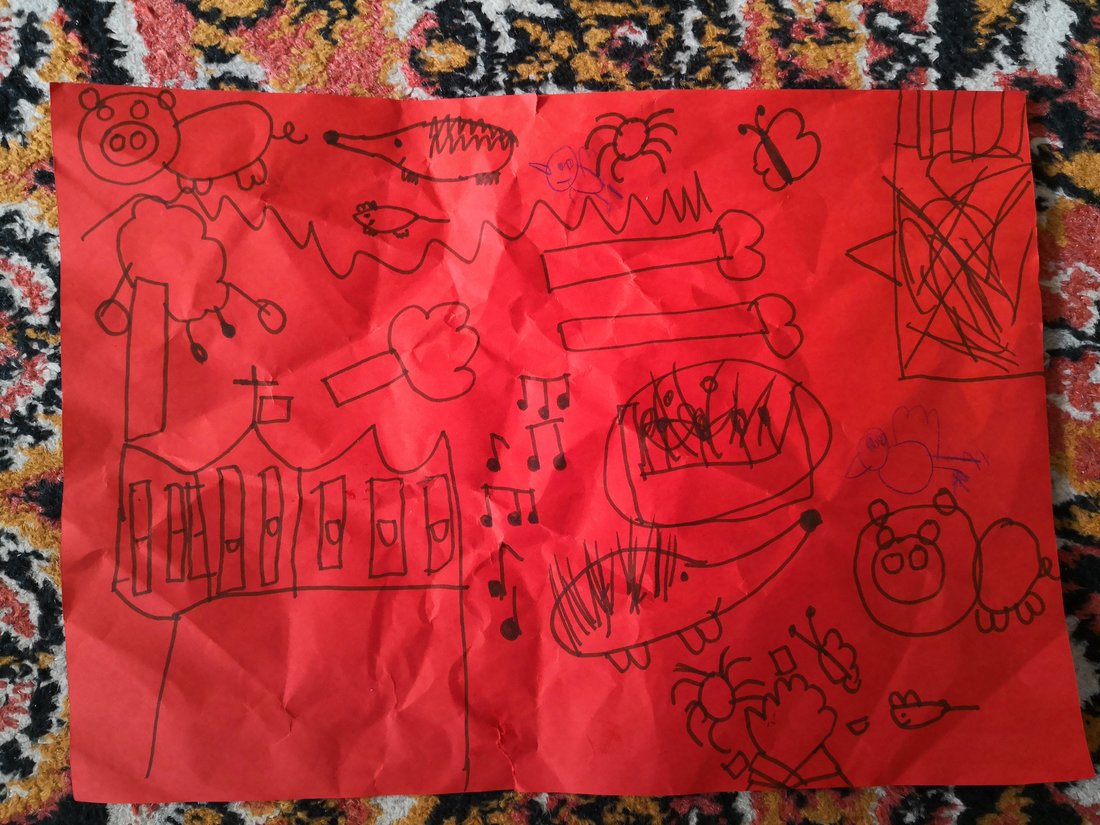

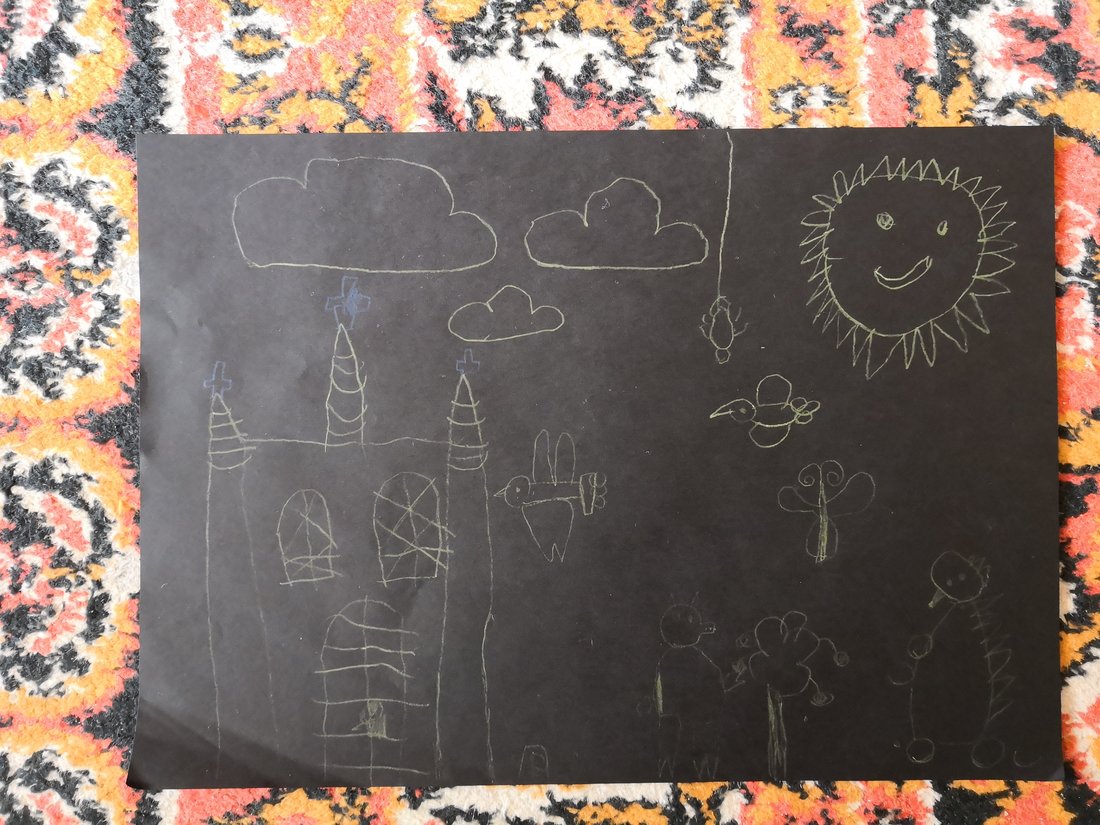

While Ausra played music of Bach, Krebs, Mendelssohn, Franck and Lefebure-Wely, I made up a fairly tale about how Pinky and Spiky built pipe organ for the kids. We had color paper and color pencils with us so the kids could draw this story themselves... It was a lot of fun... We hope they will remember this for a long time... Here are some pictures from today. Would you like to have a similar event for children in your area? Let us know your thoughts... |

DON'T MISS A THING! FREE UPDATES BY EMAIL.Thank you!You have successfully joined our subscriber list.  Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas Photo by Edgaras Kurauskas

Authors

Drs. Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene Organists of Vilnius University , creators of Secrets of Organ Playing. Our Hauptwerk Setup:

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

This site participates in the Amazon, Thomann and other affiliate programs, the proceeds of which keep it free for anyone to read.

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2011-2024 by Vidas Pinkevicius and Ausra Motuzaite-Pinkeviciene.

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed